Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Spellmount

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

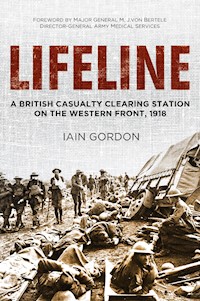

On 21st March 1918, 29th and 3rd Casualty Clearing Stations RAMC were encamped at Grévillers, just behind the front line, when Germany launched its final, massive offensive. These Field Hospitals were the lifeline to the rear for the unabated deluge of wounded which soon overwhelmed both units; all wards were full and operating theatres were working round the clock to deal with the endless queues for amputations and major surgery. In the words of Major-General von Bertele in his foreword: 'that casualty care should be managed on such a scale and at such a pace leaves the reader open mouthed.' Lifeline is a touching record of the care provided by an often exhausted but dedicated medical and nursing staff and the bravery and spirit of their patients as the hospitals, always under intense pressure, moved back and forth with the changing positions of the line during the last months of the war.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 242

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In memory of the 7,073 members of the Army Medical Services killed in action during the First World War.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

List of Plates

Abbreviations

Foreword by Major General M. J. von Bertele, QHS, OBE Director General Army Medical Services

Acknowledgements

1 The Hammer Falls

2 Retreat

3 Consolidation

4 NYDNs, SIWs and Hun Stuff

5 The Yanks are Coming!

6 Payback Time!

7 The Last Lap

8 Victory!

9 Peace

10 Epilogue

Appendix A

The British Army Medical Establishment on the Western Front

Appendix B

Extended Scale of Equipment for Casualty Clearing Stations in France

Appendix C

The bombing of the Canadian Hospital at Doullens 29/30 May 1918

Appendix D

Some Medical Statistics for the Western Front 1914–1918

Sources

Plate Section

By the Same Author

Copyright

LIST OF PLATES

Permission to reproduce illustrations used in this book is gratefully acknowledged as follows:

001 A Casualty Clearing Station on the Western Front. Daryl Lindsay © Wellcome Library, London

002 Collecting the wounded from a battlefield. Daryl Lindsay © Wellcome Library, London

003 Aerial photograph of the hospital sites at Grévillers, one on either side of the road. Note the red crosses for aerial recognition and the cemetery (lower left). © Imperial War Museum (Box 871 1918)

004 The same positions on a contemporary trench map. The castellated lines represent German trenches and the Xs are barbed wire entanglements. © National Archives

005 The hospital sites at Grévillers today with Grévillers village and church in the background (left) and the CWGC cemetery (right). The hospital railway siding would have run roughly along the dividing line of the short and long grass in the field on the left.

006 29 Casualty Clearing Station at Grévillers on 21 March 1918, the first day of the big German offensive. The wards in 29CCS and 3CCS are overflowing and the ambulance trains cannot arrive quickly enough to deal with the massive intake of casualties. Here, patients on stretchers lie in rows beside the railway siding waiting for the next train to evacuate them to a base hospital. By noon the following day, the two hospitals will have admitted more than 4,000 wounded men. © Army Medical Services Museum

007 Grévillers British War Cemetery in the early 1920s with the wooden crosses still in place. © Commonwealth War Graves Commission

008 The cemetery today.

009 No.33 Ambulance Train stands on the hospital siding at Grévillers on 27 November 1917. The following day it left for base hospital with 99 patients from 29CCS. The main Achiet-Marcoing railway line is in the foreground. © Imperial War museum (Q47147)

010 The same view today. The main line is now derelict and the hospital siding has been removed. Inset: The derelict main line.

011 An Advanced Dressing Station close behind the frontline. © Wellcome Library, London

012 A Regimental Aid Post in the trenches. © Wellcome Library, London

013 ‘Nightfall’ – A poignant picture of blinded and partially blinded men, each with a hand on the shoulder of the man in front for guidance, in a shuffling queue for treatment at a Casualty Clearing Station. © Wellcome Library, London

014 German prisoners assist British stretcher bearers to gather the wounded on a battlefield for transportation to a Field Ambulance or Casualty Clearing Station. © Wellcome Library, London

015 Casualty Collection Point on a Somme battlefield. © Army Medical Services Museum

016 An MO and a Nursing Sister attend to a patient in a CCS. © Army Medical Services Museum

017 St Andrew’s Hospital, Malta, 1917

018 & 019 The CO is front row centre between the two matrons in both groups.

020 Treating the wounded at 29CCS, Gézaincourt 27 April 1918. © Imperial War Museum

021 A Sister and an RAMC Orderly dress a patient’s wounds on board an Ambulance Train at Gézaincourt. © Imperial War Museum (Q8737)

022 A Sister attends to patients aboard Ambulance Train No.29 at Gézaincourt on 27 April 1918. The train left the following day with 128 patients. (The French “Poilu” in the top bunk was obviously enjoying the publicity as he also appears in both pictures opposite which were all taken during the same official photography shoot.). © Imperial War Museum (Q8736)

023 Awaiting the arrival of patients. © Imperial War Museum (Q8738)

024 Communications to and from the frontline.

025 The Field Service Post Card on which only the minimum amount of news was allowed to be conveyed to worried relatives at home.

026 Pressed wild flowers picked on the battlefield enclosed with a letter.

027 Lieutenant Colonel James Allman Armstrong IMS Civil Surgeon Cawnpore. (Father-in-Law of JCGC)

028 Colonel James Charles Gordon Carmichael IMS Civil Surgeon Fort William, Calcutta. (Father of JCGC)

029 Hilda Sade Carmichael (née Armstrong). (Wife of JCGC)

030 Colonel Donald Roy Gordon Carmichael. (Son of JCGC)

031 James Charles Gordon Carmichael on commissioning as a Lieutenant RAMC in 1902.

032 A kilted Highland soldier outside the Collecting Post for Walking Cases at 69 Field Ambulance amidst the desolation of the Western Front. © Wellcome Library, London

033 A Dental Officer attached to a Casualty Clearing Station. There was an acute shortage of dentists at the beginning of the war until the C-in-C instituted a recruiting drive following severe toothache for which he had difficulty in obtaining treatment. © Wellcome Library, London

034 The ‘Hospital Valley’ at Gézaincourt in which two, and sometimes three, Casualty Clearing Stations were located. The area resembled ‘a vast tented city’.

035 The disused railway halt at Gézaincourt from where a continuous succession of Ambulance Trains evacuated wounded to base hospitals, having received treatment and emergency surgery at the CCSs in the valley. The Cross of Sacrifice in Bagneux CWGC Cemetery can be seen on the left.

036 The grave of Private R.G. Crompton, West Yorkshire Regiment, who was buried in the Bagneux Cemetery, Gézaincourt on 25 April 1918. He was aged 19. The official photograph taken in the early 1920s, showing the original wooden cross, and sent to the family when they requested details. © Commonwealth War Graves Commission

037 The same grave today. © Richard Crompton

038 A photograph of Private J.W. Laurenson, Durham Light Infantry, who died of wounds in 29CCS on 27 August 1918. The photograph was left recently with the Cemetery Visitors’ Book by a relative visiting the site.

039 A view of the Bagneux CWGC Cemetery at Gézaincourt with the ‘Hospital Valley’ beyond.

040 Graves of two Coolies of the Chinese Labour Corps.

041 Graves of the Canadian Medical personnel killed in the German raid on the hospital at Doullens.

042 RAMC ambulances collect the wounded from a battlefield.

043 Soldiers struggle to free an ambulance stuck in the mud.

044 The Padre writes a letter home for a wounded soldier.

045 Personnel of 29th Casualty Clearing Station, Germany 1919. The CO in an overcoat sits between the Chaplain and the Quartermaster.

046 The French hospice at Warloy-Baillon where the officers of 29CCS slept on the floor of the porter’s lodge during their retreat from Grévillers on 25 March 1918.

047 29th Casualty Clearing Station Bonn, 1919. A ward in the converted chapel. © Imperial War Museum (Q3747)

048 The 19th century St. Marien’s Hospital in Bonn in which 29CCS was located. © Imperial War Museum (Q3746)

ABBREVIATIONS

AAMC

Australian Army Medical Corps

AB

Able Seaman

ADMS

Assistant Director of Medical Services

ADS

Advanced Dressing Station

AG

Adjutant General

AMS

Army Medical Services

ANS

Army Nursing Services

ANZAC

Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

Arty

Artillery

ASC

Army Service Corps

Asst

Assistant

AT

Ambulance Train

BEF

British Expeditionary Force

BRCS

British Red Cross Society

Brig. Gen.

Brigadier General

Bn

Battalion

CAMC

Canadian Army Medical Corps

Capt.

Captain

CCS

Casualty Clearing Station

CIGS

Chief of Imperial General Staff

C-in-C

Commander-in-Chief

CO

Commanding Officer

Col

Colonel

CP

Collecting Post

Cpl

Corporal

CWGC

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

DAG

Deputy Adjutant General

DCM

Distinguished Conduct Medal

DDMS

Deputy Director of Medical Services

DMS

Director of Medical Services

DGAMS

Director General of Army Medical Services

Div.

Division

DLI

Durham Light Infantry

DSO

Distinguished Service Order

Dvr

Driver

FA

Field Ambulance

FM

Field Marshal

Gen.

General

GH

General Hospital

GHQ

General Headquarters

GOC

General Officer Commanding

Gnr

Gunner

HQ

Headquarters

Inf.

Infantry

IMS

Indian Medical Service

KSLI

King’s Shropshire Light Infantry

Lt

Lieutenant

Lt Gen.

Lieutenant General

Lt Col

Lieutenant Colonel

L/Cpl

Lance Corporal

L/Sea.

Leading Seaman

MAC

Motor Ambulance Convoy

Maj.

Major

Maj. Gen.

Major General

MC

Military Cross

MDS

Main Dressing Station

MGC

Machine Gun Corps

MO

Medical Officer

MORC

Medical Officer Reserve Corps (US Army)

MSM

Military Service Medal

NCO

Non-Commissioned Officer

N FUS

Northumberland Fusiliers

NYD(N)

Not Yet Diagnosed (Neurological / Nervous)

NZMC

New Zealand Medical Corps

OBE

Order of the British Empire

OC

Officer Commanding

PMO

Principal Medical Officer

Pnr

Pioneer

PO

Petty Officer

POW

Prisoner of War

Pte

Private

QAIMNS

Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service

QM

Quartermaster

QMAAC

Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps

QMG

Quartermaster General

QMS

Quartermaster Sergeant

RAChD

Royal Army Chaplains Department

RAF

Royal Air Force

RAMC

Royal Army Medical Corps

RAP

Regimental Aid Post

RE

Royal Engineers

Regt

Regiment

Revd

Reverend

RFA

Royal Field Artillery

RFC

Royal Flying Corps

RGA

Royal Garrison Artillery

RHA

Royal Horse Artillery

RMO

Regimental Medical Officer

RN

Royal Navy

RP

Relay Post

RSM

Regimental Sergeant Major

RTO

Rail Transport Officer

RWF

Royal Welsh Fusiliers

Sgt

Sergeant

SH

Stationary Hospital

SIW

Self-Inflicted Wound

SMO

Senior Medical Officer

Sub-Lt

Sub Lieutenant

Surg.

Surgeon / Surgical

TAT

Temporary Ambulance Train

TC

Temporary Commission

TF

Territorial Force

TFNS

Territorial Force Nursing Service

VAD

Voluntary Aid Detachment

VC

Victoria Cross

VD

Venereal Disease

WO

War Office, Warrant Officer

WWCS

Walking Wounded Collection Station

FOREWORD

BY MAJOR GENERAL M. J. VON BERTELE,QHS, OBEDIRECTOR GENERAL ARMY MEDICALSERVICES

Anyone who has served on operations with the medical services over the last ten years will read this account of a casualty clearing station in the last months of the First World War with a mixture of awe and familiarity. All of the lessons are writ large, and most seem to have been learned at that time, but that casualty care should be managed on such a scale and at such pace leaves the reader open-mouthed. Essentially, this is a detailed account of CCS 29 (there were 74 in total and over 200 field ambulances), researched and described in intimate detail, in the final push in 1918. They were driven first one way as the Germans attacked, and then the other as the Allies, eventually joined by America, drove them out of France. At every turn the much later observation of Rupert Smith was proved true: ‘The only certain result of your plan will be casualties, mainly the enemy if it is a good plan, yours if it is not,’ and what numbers; it was not uncommon for a CCS to admit more than 1,000 casualties in a day, and to operate, treat and evacuate them all.

The DMS planners seemed up to the task; the speed of planning, of movement, anticipation, operational tempo, and opening and closing of medical units, was a prominent feature of the campaign. The preferred means of movement seems to have been rail, both for logistical moves and the evacuation of casualties. A CCS filled twenty railway wagons, and the ambulance trains could carry 700 casualties. It demonstrated the utility and flexibility of ground evacuation in an era before aviation. When rail and truck failed, the men were forced to redeploy on foot and were married up with the next trainload of medical stores that became available. It is hard to comprehend the scale of the organisational challenge in such seemingly chaotic circumstances, but in the fourth year of the war it ran with industrial precision and the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Carmichael, even found time to write to his wife in Malta, using a postal service that was quicker than that enjoyed today. Throughout, we are reminded that the sick and diseased, notably those unfortunate souls who had taken comfort from local prostitutes, formed a core of inpatients, and the VD patients even provided a useful source of unskilled labour, not afforded the luxury of rearwards evacuation.

This is an account that is immediately recognisable by the common features that persist to this day. Efficient clearance of casualties from the battlefield, their effective triage, treatment and onward evacuation, is as essential to the maintenance of the moral component now, as it was then, if armies and their commanders are to retain the ability to prosecute wars.

Major General M. J. von Bertele, QHS, OBE

Director General Army Medical Services

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As with any writer whose work depends upon extensive research, I am again made conscious of the debt of gratitude which we owe to all those dedicated people who work in the country’s libraries, museums and archives to preserve the documents which form our national heritage and to which they direct us with good nature and expertise when we seek to consult them.

I thank them all, and would particularly mention Simon Wilson of The Wellcome Trust, Vanessa Rodnight of the National Army Museum, Freddie Hollom of the Imperial War Museum, Captain Peter Starling and his staff at the Army Medical Services Museum and Ian Small of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

I am also, as usual, deeply grateful to my friends Natalie Gilbert, Ronald Dunning and John Brain for their help with research, and, as ever, to my wife Anthea for her meticulous and professional copy-editing.

Last, but not least, I must thank the present Director General Army Medical Services, Major General Michael von Bertele, for sparing the time in his very busy life to read the drafts and contribute the foreword.

Iain Gordon

Barnstaple, Devon

‘In nothing do men more nearly approach the gods than in giving health to other men.’

(Cicero)

Chapter 1

THE HAMMER FALLS

THURSDAY 21 MARCH 191829TH CASUALTY CLEARING STATION,ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS,GREVILLERS, FRANCE

At 4.40 a.m., Sister M. Aitken of the Australian Army Nursing Service was woken by a violent explosion. Her first thought was that it was an ammunition dump blowing up behind their lines, but when it was followed immediately by two further, and even louder, explosions, she realised with alarm that the British lines were under artillery bombardment from the enemy.

As she hastily got dressed, the shellfire increased in violence and intensity until the explosions merged into an almost continuous roar, defying normal conversation, making the canvas of the tents billow and strain, and the ground on which they were pitched tremble. She had only been here for two days; on Tuesday, together with three other nurses, two Australian and one British, she had joined 29th Casualty Clearing Station (29CCS) to receive their final course of instruction in anaesthesia. Life on the Third Army front had been quiet in recent months and she had expected to receive her tuition in reasonably peaceful and relaxed surroundings. Her last appointment had been at No.1 General Hospital in Étretat, a quiet village on the coast of Normandy and many miles from the frontline. She had never been this close to the battlefields before, let alone come under enemy fire, and she felt a strange mixture of anxiety and elation.

For all she knew, the bombardment might include gas shells; there had been several cases of mustard gas poisoning admitted during the two days she had been in the hospital. So, once dressed, she picked up her gas mask and hurried to the wards through the rows of shaking bell tents and marquees to report to the duty night sister. Throughout the camp, nurses and RAMC orderlies were emerging from tents in varying stages of undress, all intent on getting to their duty stations and finding out what was going on.

When Sister Aitken reached the wards, she saw that the sister-in-charge, Miss F.M. Rice, a senior sister in the Territorial Force Nursing Service (TFNS), was already there, upright, immaculate and imperturbable in her spotless, starched uniform. She was attempting, above the thunder of the bombardment, to converse with Major (Maj.) G.L.K. Pringle of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), the second-in-command who, only the day before, had been promoted from captain to major. She could not hear what they were saying but, from their gestures, she understood that they were discussing the movement of the patients in the ward.

There were 246 patients in the hospital, which was about the average. As its name implied, the purpose of a casualty clearing station was not to provide long-term care for the sick and wounded, but to inspect and renew dressings which may have been applied hastily at a trench Regimental Aid Post (RAP), or by a stretcher bearer; to undertake urgently needed surgery and to get the patients evacuated from the battle zone and back to a base hospital, well behind the lines, as quickly as possible. It was unusual for a patient to spend more than a day or two in a CCS before being loaded onto an ambulance train for evacuation. Sometimes convoys of motor ambulances, or cars for the walking wounded, would have to be used but, with the poor state of the roads and the crude suspension of motor vehicles at the time, it was a painful form of transport for severely wounded men. The majority of limb amputations were undertaken in the operating theatres of casualty clearing stations and, where transport had to be by motor ambulance, it was not uncommon for a nurse to travel with a patient to hold up what remained of a limb throughout the journey to cushion it from the bumps. For this, among other reasons, casualty clearing stations were usually situated beside, or conveniently close to, a railway line.

As Sister Aitken stood waiting for instructions, there was an explosion even louder than those before; the marquee lurched violently and, with a shriek of ripping canvas and a blast of night air, a piece of shrapnel about the size of a man’s hand flew across the ward, missing the head of the sister-in-charge by about 6in. It smashed through the duckboards covering the floor beyond and buried itself a foot deep in the ground. Miss Rice did not flinch and, having made sure that the shrapnel had done no harm to any of her patients or staff, continued her attempted conversation with Major Pringle as if nothing untoward had happened. That, thought Sister Aitken, showed the true professionalism born of a lifetime of discipline and dedication to her calling. She could see by the faces of the patients lying in the beds that the incident had been noticed and that it had had an immediate effect on morale in the ward.

The duty night sister bustled into the ward and, after a hurried consultation with Miss Rice and Major Pringle, beckoned Sister Aitken over and told her to join Sister B. McMunn and Staff Nurse L.A. Stock in the post-surgical ward, where they were already starting to prepare the patients for evacuation.

The enemy bombardment may have come as a surprise to Sister Aitken, but it was no surprise to the commanding officer (CO), Lieutenant Colonel (Lt Col) J.C.G. Carmichael RAMC. A major spring offensive by the enemy had been expected for weeks and it was simply a question of ‘when’ rather than ‘if’. Intelligence sources had reported an increase in troop movements behind the enemy lines in recent weeks and a party of senior German officers had been seen scrutinising the British positions along the Third and Fifth Army fronts. It could only mean that the expected attack was imminent.

The day before, the CO had received warning from headquarters (HQ) that he should be prepared for a move at very short notice. He had immediately ordered all off-duty staff to start packing unused stores and equipment ready for rapid loading. He had not gone to bed that night and had visited every ward in the hospital, giving encouragement to his own men who had also sacrificed a night’s sleep to start the packing process.

The British Third Army, guarding a 28-mile section of the Western Front, consisted of twelve Divisions, plus two in reserve. The normal allocation of casualty clearing stations was one for each division and so, consequently, there were twelve CCSs supporting the Third Army. Two of these were further forward than 29CCS — 48CCS at Ytres and 21CCS at Beaulencourt. Both came under heavy shelling on 21 March and were evacuated the same day, leaving 29CCS as the most forward hospital on the Third Army front.

There were two CCSs at Grévillers, just outside the village on the Bapaume road — 29CCS on one side of the road and 3CCS on the other. The two hospitals shared access to the light railway siding from which most of their patients started the long journey back to base hospital. They also shared use of the burial ground for those who would sadly never make the journey.

The initial aim of the enemy bombardment was to disable the British artillery positions behind the lines. The main bulk of the shelling therefore passed over the heads of personnel at 29CCS and, although there were some near misses and some damage to tents and equipment, there were no casualties in the hospital. Further back, where the British gun positions were, the hospitals were less fortunate. At 45CCS at Achiet-le-Grand, less than 2 miles from Grévillers, twenty-five were killed and eleven injured on the morning of the 21st.

At 6 a.m. the sound and feel of the bombardment changed. The veteran soldiers in the wards who had long experience in the frontline knew immediately what was happening: the enemy had stopped bombarding the British artillery positions in the rear and were now shelling the British frontline trenches. The shells were no longer howling overhead; the explosions sounded closer and in the opposite direction. The staff at 29CCS knew that the casualties would soon start arriving.

At 7 a.m. the first men arrived – straggling columns of walking wounded, hobbling on shattered legs and supported by mates on either side; heads swathed in bandages with ugly red stains seeping through; men clutching bloody field dressings to gaping wounds in chests and abdomens, or nursing shattered arms in makeshift slings. Then came the more seriously injured – crying out in pain or moaning gently in morphine-induced demi-peace; borne on stretchers carried by tin-hatted soldiers with Red Cross armbands.

The casualties were met as they arrived and the triage sisters assessed their condition. Those in need of critical surgery joined the stream for the two operating theatres where the surgical teams were hard at work. In the first theatre, the surgeons Captains Littlejohn and Mowat-Biggs, and in the second Captains Roe and Walker, supported by their experienced teams of theatre sisters and orderlies, worked throughout the day without a break.

In other treatment areas, doctors, nurses and orderlies applied splints, dressed wounds and did what they could to ease the pain of injured and badly shocked men. In another area, seriously wounded men with no hope of recovery were made as comfortable as possible, their final moments often eased by the presence of a nurse to talk to them and hold their hands, or by comforting words and spiritual reassurance from one of the three chaplains attached to the hospital. By 10 a.m. the fifteen wards of the hospital were almost full and stretchers were waiting on the ground outside the reception tent.

At 3CCS across the road, the position was just the same: their wards were full and rows of stretchers were piling up on the ground outside the reception area. Though all the medical staff were working flat out, the influx of casualties was too great for them to keep up. The sister-in-charge at 3CCS, Miss W.M. Gedye, a regular officer in Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), sent a messenger to Miss Rice at 29CCS asking whether she could help out with nurses or beds? But their situation was exactly the same.

At 7 a.m. the enemy bombardment eased, but the influx of injured men did not abate. Then, at 9.35 a.m., 3,500 enemy mortars opened fire on the British frontline, followed by, five minutes later, by waves of German infantry pouring across no-man’s-land to the British trenches. They were met by determined British soldiers with Lee Enfield .303 rifles with sword bayonets fixed. The carnage on both sides was appalling. The triage sisters in the reception area noted that the nature of wounds was changing: the majority of earlier casualties had been as a result of shrapnel from artillery shelling; now the admissions showed signs of violent, hand-to-hand fighting, with gunshot wounds the predominant injuries. Similarly, as the earlier casualties had tended to be gunners from the beleaguered Royal Artillery gun emplacements behind the lines, the admissions now were largely from the frontline infantry battalions of the 6th and 51st (Highland) Divisions such as the 2nd Durham Light Infantry, 1st King’s Shropshire Light Infantry, 1st Leicesters or 4th Seaforths.

For full regimental names see index.

At 29CCS the pressure of patients waiting for amputations and major surgery was so intense that, by noon, the two operating theatres clearly could not cope. It was vital for these men to receive surgery here at the CCS; without it, wounds could turn gangrenous on the journey and patients would be die en route to the base hospital.

So the CO ordered the post-operative ward to be prepared as an emergency theatre and detailed two of his medical officers, Captain (Capt.) Dill and Lt Brockwell, to stand in as an emergency surgical team. Miss Rice detailed four nurses and four orderlies to support them. With two more operating tables in action, the queues for surgery slowly shortened.

Outside the camp, Sergeant (Sgt) E.H. Boswell RAMC worked tirelessly to supervise the smooth running of the motor convoys, the queues of stretcher bearers bringing casualties from the front and those which were transporting the wounded who had already been treated in the hospital to No.7 Ambulance Train (AT), which stood in the siding next to the camp. When full, it would evacuate the casualties to the base hospital at Doullens. At the siding, Sgt J. Orr RAMC checked the patients onto the train and marked off their names on his dispersals list.

On board the train, nurses and orderlies received the patients and made them as comfortable as possible in the rows of three-tiered cots lining the sides of the carriages. Getting badly wounded patients into the top cots was one of the jobs the nurses liked least: it was almost impossible to transfer a badly wounded man from a stretcher to a top cot without causing him acute pain and the upper tier was, therefore, whenever possible, reserved for less serious cases.

The ambulance train had its own permanent staff of doctors, nurses and orderlies, messes for the medical staff, cookhouses to prepare food for staff and patients, and to provide a continuous supply of hot water for clinical purposes, a pharmacy, a stores wagon and a tiled, emergency operating theatre which could, in extreme circumstances, be used for procedures when the train was moving. A typical ambulance train had sixteen carriages and accommodated about 400 patients in wards of thirty-six cots. The centre tier of cots could be folded up to take sitting cases on the bottom row.

As soon as the train was full, a locomotive arrived and pulled the carriages out towards the main line. Within half an hour another ambulance train, 38AT, had drawn into the siding and the loading of patients started again.

The casualties arriving from the frontline brought gloomy news: the enemy was in immense strength and was breaking through all along the British lines. At 1 p.m. the CO received orders from the HQ of the Director Medical Services (DMS) to clear all patients from 29CCS and prepare to hand over the site to a field ambulance (FA). Admissions ceased and casualties were diverted to 3CCS across the road. In the course of the day, 29CCS had admitted 949 patients on top of the 246 already in the hospital before hostilities started. The admissions included twelve mustard gas cases, seven Indians of the 41st Indian Labour Company and one wounded French civilian who had been unlucky enough to get in the way of the conflict. The two ambulance trains evacuated 710 patients and a further 451 were transferred to 56CCS at Dernancourt (known to the British as Edgehill).