28,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

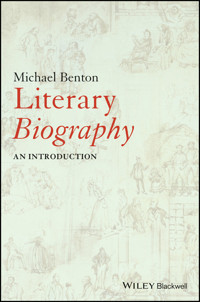

Literary Biography: An Introduction illustrates and accounts for the literary genre that merges historical facts with the conventions of narrative while revealing how the biographical context can enrich the study of canonical authors.

- Provides up-to-date and comprehensive coverage of issues and controversies in life writing, a rapidly growing field of study

- Offers a valuable biographical and historical context for the study of major classic and contemporary authors

- Features an interview with Wilfred Owen's biographer, Dominic Hibberd; a gallery of literary portraits with commentaries; close readings that illustrate the differences between fiction and biography; speculation about likely future developments; and detailed suggestions for further reading

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 546

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title page

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Literary Biography Now and Then

The Cinderella of Literary Studies

The Rise and Rise of Literary Biography

Dr Johnson: Biographer, Theorist and Subject

Virginia Woolf: Time, Memory and Identity

2 Life [Hi]Stories: Telling Tales

Aspects of Narrative

The Naked Biographer

Inventing the Truth

3 Reading Biography

Biographer, Biography and the Reader

Imagining Blake

Problems of a Hybrid Form

Reading Lessons

4 Literary Biomythography

Biomythography

Myth-Making: The Brontë paradigm

Variations on the Theme

Conclusions

5 Inferential Biography: Shakespeare the Invisible Man

Virtual Shakespeares

The Implied Author: Inferential Biography

The Limits of Imagination

6 Literary Biography and Portraiture

Sister Arts

Art to Order

7 Comparative Biography: Dickens’s ‘Lives’

The Victorian Dickens

The Modern Dickens

The Post-Modern Dickens

Lives and Times

8 Literary Auto/Biography

Acts of Self-Creation in Wordsworth and Joyce

Wordsworth’s ‘biographic verse’

Joyce’s ‘artist, like the God of creation’

Masks and Metaphors

9 Biography in Practice

An Interview with Dominic Hibberd, author of

Wilfred Owen: A New Biography

Living with the Subject

Imagining Wilfred

Matters of Life and Death

10 Authorised Lives

The Life of Graham Greene

by Norman Sherry

Bernard Shaw

by Michael Holroyd

T. S. Eliot

by Peter Ackroyd

Orwell: The Life

by D. J. Taylor

Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life

by Andrew Motion

Contemporary Lives

11 Literary Lives: Scenes and Stories

Dinner with Dr Johnson and John Wilkes

Dinner with Mrs Ramsay

Biography and Fiction

12 Biography and the Future

Select Bibliography

Further Reading

General Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 03

Figure 3.1 Biography: a generic dualism

Chapter 06

Figure 6.1 Sir Joshua Reynolds,

Samuel Johnson

(1756–1757). Oil on canvas, 127.6 × 101.6 cms. National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 6.2 Cassandra Austen,

Jane Austen

(

c

.1810). Pencil & watercolour, 11.4 × 8.0 cms. National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 6.3 James Andrews/Lizars,

Jane Austen

(1870). Steel-engraved portrait for Austen-Leigh’s

Memoir.

National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 6.4 Henry Weekes,

Memorial to Percy Bysshe Shelley

(1854). Marble. Priory Church, Christchurch, Hampshire

Figure 6.5 Thomas Phillips,

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron

(1835). Oil on canvas, 76.5 × 63.9 cms. National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 6.6 Joseph Severn,

John Keats

(1821). Oil on canvas, 56.5 × 41.9 cms. National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 6.7 John Taylor (attributed),

William Shakespeare

(

c

.1600–1610). Oil on canvas, 55.2 × 43.8 cms. National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 6.8 Robert William Buss,

Dickens’s Dream

(1875). Watercolour, 70.0 × 90.0 cms. The Charles Dickens Museum, London

Figure 6.9 Vanessa Bell,

Virginia Woolf

(1912). Panel, 39.5 × 33.0 cms. National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 6.10 Patrick Heron,

T. S. Eliot

(1949). Oil on canvas, 76.2 × 62.9 cms. National Portrait Gallery, London. Copyright The Estate of Patrick Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2008

Figure 6.11 Branwell Brontë,

The Brontë Sisters

(

c

.1834). Oil on canvas, 90.2 × 74.6 cms. National Portrait Gallery, London

Chapter 11

Figure 11.1 William Hogarth,

John Wilkes Esq

. (1763) Engraving, 31.8 × 22.2 cms. The British Museum

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

Literary Biography

An Introduction

Michael Benton

This paperback edition first published 2015© 2009 Michael Benton

Edition history: Blackwell Publishing Ltd (hardback, 2009)

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Michael Benton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Benton, Michael, 1939–Literary biography: an introduction / Michael Benton. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-9446-4 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-1190-6011-6 (paperback)1. Authors, English–Biography–History and criticism–Theory, etc. 2. English prose literature–History and criticism–Theory, etc. 3. Authors–Biography–Authorship. 4. Biography as a literary form. I. Title. PR756.B56B46 2009 820.9′492–dc22

2009009386

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover image: Dickens Dream

Those parallel circumstances and kindred images, to which we readily conform our minds, are, above all other writings, to be found in narratives of the lives of particular persons; and therefore no species of writing seems more worthy of cultivation than biography, since none can be more delightful or more useful, none can more certainly enchain the heart by irresistible interest, or more widely diffuse instruction to every diversity of condition.

Dr Samuel Johnson, The Rambler, No. 60, Saturday, October 13, 1750

As everybody knows, the fascination of reading biographies is irresistible. No sooner have we opened the pages … than the old illusion comes over us. Here is the past and all its inhabitants miraculously sealed as in a magic tank; all we have to do is to look and to listen and to listen and to look and soon little figures – for they are rather under life-size – will begin to move and to speak, and as they move we shall arrange them in all sorts of patterns of which they were ignorant, for they thought when they were alive that they could go where they liked; and as they speak we shall read into their sayings all kinds of meanings which never struck them, for they believed when they were alive that they said straight off whatever came into their heads. But once you are in a biography all is different.

Virginia Woolf, ‘I am Christina Rossetti’, in Collected

Essays, IV, 1967: 54

The trawling net fills, then the biographer hauls it in, sorts, throws back, stores, fillets and sells. Yet consider what he doesn’t catch: there is always far more of that. The biography stands, fat and worthy-burgherish on the shelf, boastful and sedate: a shilling life will give you all the facts, a ten pound one all the hypotheses as well. But think of everything that got away, that fled with the last deathbed exhalation of the biographee. What chance would the craftiest biographer stand against the subject who saw him coming and decided to amuse himself?

Julian Barnes, Flaubert’s Parrot, 1985: 38

Illustrations

3.1

Biography: a generic dualism

6.1

Sir Joshua Reynolds,

Samuel Johnson

6.2

Cassandra Austen,

Jane Austen

6.3

Engraving of

Jane Austen

, after Cassandra’s portrait

6.4

Photograph,

Memorial to Percy Bysshe Shelley

by Henry Weekes

6.5

Thomas Phillips,

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron

6.6

Joseph Severn,

John Keats

6.7

John Taylor (attributed),

William Shakespeare

, the ‘Chandos’ portrait

6.8

Robert William Buss,

Dickens’s Dream

6.9

Vanessa Bell,

Virginia Woolf

6.10

Patrick Heron,

T. S. Eliot

6.11

Branwell Brontë,

The Brontë Sisters

11.1

William Hogarth,

John Wilkes

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the editors of the following journals who have granted me permission to reproduce revised versions of articles that have appeared in their publications.

The Journal of Aesthetic Education for ‘Literary Biography: The Cinderella of Literary Studies’, which originally appeared in Vol. 39, No. 3, Fall 2005 and now features in parts of Chapters 1 and 2; and for ‘Reading Biography’, which originally appeared in Vol. 41, No. 3, Fall 2007 and now forms the bulk of Chapter 3. Both are used with the permission of the University of Illinois Press.

Auto/Biography for ‘Literary Biomythography’, which was first published in Issue 13, No. 3, 2005 and is reprinted as Chapter 4.

I am also indebted to the following galleries for permission to reproduce paintings and engravings from their collections:

The National Portrait Gallery, London for illustrations 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 6.5, 6.6, 6.7, 6.9, 6.10, 6.11.

The Estate of Patrick Heron and DACS for 6.10.

The Charles Dickens Museum, London, for 6.8.

The British Museum, London, for 11.1.

I am especially grateful for the kindness of friends in helping me to complete this book. My thanks go to Dominic Hibberd for his willingness and patience in being interviewed about his biography of Wilfred Owen and for the fascinating insights into his ways of working; and to Geoff Fox and Pam Barnard who read each chapter in draft form and whose detailed marginalia and general comments have both sharpened the text and saved me from a number of errors and obscurities; any that remain are my own. Finally, my biggest debt is to my wife, Jette Kjeldsen, for her unmatchable combination of scrupulous reading, trenchant criticism and strong support.

Introduction

No-one, it seems, has a good word to say for biographers, not even the biographers themselves. That their subjects are often critical, even abusive, is only to be expected: ‘biografiends’ Joyce called them; ‘a disease of English literature’ was George Eliot’s diagnosis of their work (quoted in Salwack, 1996: 37). But for biographers to turn upon themselves is uniquely odd. Perhaps the current spate of self-vilification was triggered by guilt stirred by Janet Malcolm’s analysis of the Plath biographies in which she describes the biographer as a ‘professional burglar’ and accounts for the popularity of the genre by its prurient and ‘transgressive nature’ (Malcolm, 1995: 9). Whatever the cause, Dale Salwack’s (1996: 6) book on literary biography begins with a catalogue of quotations from writers disgusted by biography; Michael Holroyd (2003: 3–9) plays devil’s advocate in his entertaining ‘The Case Against Biography’; and Mark Bostridge’s (2004) collection of essays by practitioners is replete with self-conscious masochism. His Preface describes biography, in a tone of nervous playfulness, as a ‘vice’ and acknowledges that the biographer is often spoken of ‘as a scoundrel’. Then, successive biographers indulge themselves in bouts of literary flagellation. Here are half a dozen of them. They see themselves as ‘voyeurs’ (pp. 7, 44), as ‘vultures’ (pp. 9, 54) and, in a string of equally nasty names, as ‘scavenger, jackal, vampire, garbage-collector’ which, Hilary Spurling concedes, are ‘all of them valid up to a point’ (p. 68)! They are seen, too, as guilty of a ‘biographical love’ between biographer and subject that is ‘obsessive, possessive, irrational and perverse’ (p. 38), which, in turn, may lead to ‘a narcissist’s wedding’ (p. 12). It is little wonder that the issue of such a marriage is likely to be a malformed parasite: ‘intrusive, trivial, irrelevant and somehow immoral’ (p. 50).

Faced with the practitioners’ lack of self-confidence, their subjects’ frequent abuse, and the scepticism of academia, this defensiveness is understandable. However, by definition, anyone writing or reading a biography assumes the relevance of the life to the works as part of the historical and cultural context of literature. But it is an assumption that begs basic questions about the nature of the genre and what it offers the reader. It is these questions that this book sets out to explore. Literary Biography: An Introduction has two purposes: the main one is to discuss the principal generic issues in a literary form of ambiguous nature and uncertain status; the subsidiary and complementary aim is to show how the biographical context can enrich the study of familiar canonical authors whose lives and works mutually illuminate each other. As the title indicates, the book is intended as an introduction for students and general readers. It is not an attempt to theorise biography. This would require consideration of the genre both from a historiographical point of view and, in a literary perspective, from a historicist stance. Such an exploration would, no doubt, be revealing in its complementary concerns for the textuality of historical representation and the historicity of biographical texts. But it is an exploration beyond the scope of this book. Where I have drawn upon literary theory – especially in Chapters 2 and 8, for example – I have aimed to do so in language that is accessible without oversimplifying the ideas.

The book is selective, concentrating on those authors and biographers whose writings open up the key generic issues. My principal examples are taken from the mainstream literary canon – Shakespeare, Dickens, Blake, Wordsworth, the Brontës, and a range of twentieth-century authors. Major biographers from Dr Johnson, Boswell and Woolf to Holroyd, Holmes and Lee are also drawn upon extensively. The book is selective also in that the majority of subjects and biographers are British or Irish. I have found no place to discuss the distinguished ‘Lives’ of Henry James by Leon Edel, or of Edith Wharton by Hermione Lee, let alone biographies from European or Commonwealth sources. There are, of course, losses here; but in the competition for space, my aim has been to illustrate different aspects of literary biography with examples that will be most familiar to readers coming new to the genre. There are also practical reasons for the selections I have made. First, there are many more biographies about these subjects, stretching over different historical periods, making the study of the genre richer, more demanding, and more amenable to the teasing out of its characteristics. Secondly, the works of these writers are both well known to the wider reading public and specified on course programmes year after year, so that readers are likely to find more points of contact and interest in these ‘Lives’ than in any others.

How far can information about a poet or novelist be expected to clarify the source of the works and illuminate the nature of the poetry or fiction that we read? T. S. Eliot discussed this question in ‘The Frontiers of Criticism’ (1957), distinguishing between the ‘explanation’ of origins and context, seeing it as ‘preparation’ for the ‘understanding and enjoyment of literature’ which, he emphasises, is unique to each individual reader: ‘There are … many facts about which scholars can instruct me which will help me to avoid definite misunderstanding; but a valid interpretation, I believe, must be at the same time an interpretation of my own feelings when I read [a poem]’ (pp. 49–50, Eliot’s italics). Eliot acknowledges the uses of biography but also sees the danger of it becoming a barrier to the appreciation of the works, either through information overload, or through falsely ‘explaining’ poems or novels in non-literary, biographical terms (p. 52). The biographical context of Eliot’s remarks is itself significant. They occurred in a lecture to some 14,000 (!) people in a baseball stadium at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis and, as Eliot’s biographer comments, no doubt with the memory of an interpretation of The Waste Land in mind that provoked him to warn ‘against too much psychological or biographical conjecture in the explication of poetry’ (Ackroyd, 1985: 317). Reading the life in the works or reading the works through the life are the Scylla and Charybdis between which literary biographers must navigate. Unlike their counter-parts in political or military fields, they sail in uniquely dangerous waters. To one side, they face the hard rocks of historical data which they ignore at their peril; to the other, a whirlpool of imaginative literature which, for biographical purposes, is of uncertain depth and relevance. Maintaining a steady, discriminating course which acknowledges the importance of both bodies of evidence, without being subsumed by either, is the special skill demanded of the literary biographer.

* * *

The twelve chapters which make up this book exist in a federal relationship – independent essays that set out to give a sense of the historical development of the genre, to describe and account for its main characteristics, and to illuminate its connections with the arts of fiction and portraiture. Given the variations in the genre, any attempt to update the efforts at a typology, made in the past by Clifford (1962) and Edel (1984) among others, seems inappropriate. Instead, the diversity is best served by viewing literary biography from a range of perspectives – historical, comparative, inferential, auto/biographical and so on. As in any federation, there are not only different roles but also contrary emphases, and occasional dissenting voices. So, here, the roles of the first three chapters are to sketch the evolution of the genre, to introduce the principal traits of a hybrid form that lies between history and fiction, and to look at the consequences for the reader. In subsequent chapters, there are contrary emphases, for example, in listening to a biographer speaking about his practice, while others struggle with the dearth of hard evidence in their search for Shakespeare, or read the lives of their subjects alongside, behind or against the autobiographical images projected in the works. And, in Chapter 4, there is a measure of dissent from the whole biographical project in the subversive argument for the inevitable mythologizing of literary subjects. Yet, implicit in the notion of biomythography is the view that the genre is an art supported by elements of craft, rather than vice versa. It is this that holds this federal relationship together and is the stance adopted throughout this book.

Chapter 1 begins with a discussion of the ambiguous status of literary biography – a genre in vogue with the reading public yet still treated with a mixture of suspicion and disdain in many academic circles. It offers a historical sketch, identifying three phases of particular importance in the mid-eighteenth century, the early twentieth century and the present day. The contributions of the two major figures, Dr Johnson and Virginia Woolf, are then considered both for their theoretical essays and in two key works, The Life of Savage and Orlando, in order to show where the main issues in literary biography originate and how they have developed.

Using concepts drawn from narratology, Chapter 2 shows how biography’s handling of life stories is both like and unlike that of fiction. Narrative is not neutral but imposes a shape on ‘real life histories’ involving selection, continuity, coherence and closure. These four elements are discussed with particular reference to examples of the beginnings, middles and endings of biographies of the Brontës, Thomas Hardy and Jane Austen. Two features unique to reading literary biography are identified: how readers must accommodate the image of the ‘implied author’ constructed from the author’s works with that presented by the biography; and the asymmetrical time-lines of the author’s ‘life narrative’ and ‘literary narrative’. Literary biography is then shown to occupy an uncomfortable position between factual and fictional truth, illustrated in different ways from Thomas Hardy’s self-ghosted biography and from Mrs Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë.

Chapter 3 considers the dualistic nature of the genre from the point of view of the problems and benefits it presents for the reader. The first part conceptualises the communication between biographer and reader that is represented in the text. It argues that the hybrid character of biography, a cross between verifiable historical information and aesthetic narrative, is also reflected in the twofoldness of the writer’s task and the reader’s role. The second part shows how this model works in practice through examining two recent biographies of William Blake, one by G. E. Bentley, Jr with a ‘documentary’ emphasis, the other by Peter Ackroyd with an ‘aesthetic’ emphasis. It exemplifies the differences, in particular by contrasting how these two accounts deal with one of Blake’s central concepts, the ‘Two Contrary States of the Human Soul’, which provides the theme for his Songs of Innocence and Experience. The third part considers two potential problem areas that derive from biography’s hybrid form: the handling of historical data within the time-frame of the subject’s life; and the difficulties of dealing with the ‘inner life’ of the subject’s mind and feelings. A brief final section weighs up the problems and benefits of studying literary biography and concludes that this genre offers readers uniquely important reading lessons.

Myth-making is endemic in the life histories of novelists and poets. Literary biographies are complicit in the process even when they seek to demythologise their subjects. Chapter 4 outlines a five-phase development in the Brontë myth as the paradigm of ‘biomythography’. Life-writings about Byron, Dickens and Sylvia Plath are then shown to follow a similar pattern and to exemplify, respectively, the characteristics of celebrity, idolatry and martyrdom which typify myth-making and which literary biography both helps to create and attempts to expose. The chapter concludes with ten brief reflections on the notion of biomythography which substantiate its claim to subvert any concept of life-writing based on a simplistic account of supposed ‘facts’.

Chapter 5 is untypical in the prominence it gives to explicit discussion of a writer’s works. To a greater or lesser extent, all literary biographers draw inferences from their subject’s writings; but Shakespeare’s invisibility as a man means that his plays and poems become the prime source of insight into the mind that created them. Accordingly, the chapter summarises the evidence for the ‘life’, such as it is, and then discusses what recent biographers infer about the thinking of their implied author in a representative selection of his works. A final section assesses the patterns of thinking in Shakespeare’s works which modern biographies reveal, in particular, the increased sophistication in language and thinking around the middle of his career, and his typical mode of representing ideas through the dialectical conflict of characters and situations.

Chapter 6 on the relationship between biography and portraiture consists largely of a gallery of ten portraits of poets and novelists, each with an accompanying commentary which links these images to the lives, works or times of the writers and to the artistic conventions of the period when the paintings were created. Portraiture is seen as veering uneasily between aesthetic and referential values. The chapter questions the common notion of these ‘sister arts’, finding some similarities in the cultural motivation behind them and in the uncomfortable position which both occupy within the literary and visual arts while, at the same time, recognising their role in canon formation within literary history, as well as their broad cultural appeal.

Chapter 7 develops the theme of ‘lives and times’, acknowledging that each age rewrites the biographies of its favoured authors in ways which reflect the mores and literary conventions of the period. Any of the major nineteenth-century novelists could be the focus, but Dickens is taken as a particularly interesting example since not only have there been recurring ‘Lives’, but there is also a fascinating biographical conundrum to be explored in the relationship between the private, domestic family man, the even more private literary man at his writing desk, and the public man of affairs recognised by all (and not least by himself) as a giant of the Victorian Age. These relationships are discussed in respect of three major biographies: the Victorian Dickens of John Forster, the Modern Dickens of Edgar Johnson, and the Post-modern Dickens of Peter Ackroyd.

Self-representation in autobiographical literary works requires the biographer of the author to discriminate between the subject as a historical person and the persona projected into the text and mediated by literary technique. The difficulties are particularly acute when the author’s self-creation is dedicated to accounting for the growth and development of an artistic life. Chapter 8 focuses upon William Wordsworth’s The Prelude and James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man as the two seminal texts and considers the implications for biographers who must view the lives of their subjects through an autobiographical screen. Following suggestions by Paul de Man, it argues that autobiographical writing is both ‘mask’ and ‘metaphor’ and it draws some conclusions about literary auto/biography, concentrating particularly upon the gaps and temporal qualities of narrative, the synthetic operation of memory, and the effect of literary forms and language in the self-creation of the subject.

In the interview recorded in Chapter 9, we can listen to a biographer’s reflections upon the practice of his craft – or, should one say, his art? For one of the issues that arises from the conversation with Wilfred Owen’s biographer, Dominic Hibberd, is his role in relation to his subject, in this case, one that lies somewhere between the detached historian and the ardent storyteller. The conversation covers three broad areas: first, the development of the biographer’s initial interest in the subject, the handling of sources, the management of data and the process of composition; secondly, the main themes that emerge in the portrait of Owen – his reading, his religious upbringing, his sexual orientation, his class-consciousness – and how they bear upon his writing; and thirdly, some wider generic issues such as the justification for a new biography, and the relationship that develops between the biographer and the subject.

Chapter 10 considers five modern biographies of twentieth-century subjects – Graham Greene, Bernard Shaw, T. S. Eliot, George Orwell and Philip Larkin. It gives a critical pen portrait of each writer as seen through the eyes of their biographer and sets each ‘Life’ in the context of the literary estate that has (or in one case, has not) sanctioned its publication. Some tentative conclusions are then drawn about how biographers respond to their subject’s literary persona and about the different relationships biographers forge with authors and their literary estates.

Chapter 11 revisits the relationship between history and fiction in life-writing initiated in the opening two chapters. It focuses on the making of scenes and stories as the fundamental building blocks in biography. It pursues this theme through close readings of two famous dinner parties: Boswell’s account of Dr Johnson’s meeting with John Wilkes, and Virginia Woolf’s description of Mrs Ramsay’s dinner party in To The Lighthouse. The analyses of the theatrical scenes of the one and the painterly scenes of the other highlight the similarities and differences in scene-making in biography and fiction.

The final chapter gives a brief summary of the main themes of earlier chapters and speculates about future directions in literary biography. However literary biography is represented in the dualisms of history and fiction, craft and art, the life and the works, its hybrid nature asserts itself. This generic ‘looseness’ suggests that, despite its inbred conservatism, twenty-first-century biography may develop in new ways in which, as in Jonathan Coe’s ‘story of B. S. Johnson’, the ‘Life’ is not represented in a smooth narrative but reflects, in its style and form, something of the jaggedness of the subject’s own life and work. Or, as exemplified by Nicholl on Shakespeare, Bodenheimer on Dickens and Wroe on Shelley, the conventional chronology of the life narrative is set aside as these biographers employ different means to probe beneath the continuity of its events.

The question of the difference between non-fiction narrative and fiction remains the central one. ‘All good biographers struggle with a particular tension between the scholarly drive to assemble facts as dispassionately as possible and the novelistic urge to find shape and meaning within the apparently random circumstances of a life. We make sense of life by establishing “significant” facts, and by telling “revealing” stories’ (Holmes, in France & St Clair, 2002: 16–17). As the examples discussed in this book amply demonstrate, the biographer’s task is more complex than that of the novelist. If we allow that biography is an ‘art’, we must also recognise that the creative impulse expresses itself in a different way from that of the novelist. To develop a point made by David Cecil, the novelist’s creativity shows itself mainly in invention, in the power to create characters, to put them in scenes, and to tell stories about them; the biographer’s creativity shows itself in interpretation, in a capacity to discover in the scenes and anecdotes and the mass of other raw material the dominant, thematic life story to be fashioned into a work of art. Cecil continues: ‘Like the maker of pictures in mosaic, his [the biographer’s] art is one of arrangement; he cannot alter the shape of his material, his task is to invent a design into which the hard little stones of fact can be fitted as they are’ (Cecil, in Clifford, 1962: 153). The analogy is apt: no-one would deny that a mosaic is a work of art; equally, no-one can ignore the amount of sheer craft that goes into its composition.

1Literary Biography Now and Then

The Cinderella of Literary Studies

There are no prizes for guessing who are the two ugly sisters: criticism, the elder one, dominated literary studies for the first half of the twentieth century; theory, her younger sister, flounced to the fore in the second half. One scorned Cinderella’s very existence as ‘the biographical fallacy’; the other attempted her assassination by announcing the ‘death of the author’. Meanwhile, ‘Cinders’, who had been doing the chores for centuries, was magically transformed, decked out in new clothes by Michael Holroyd, Richard Holmes, Claire Tomalin, Hermione Lee, Peter Ackroyd et al. and, as the millennium approached, celebrated and admired on all sides. Two decades ago, as Malcolm Bradbury (1988) pointed out, we seemed to live in two ages at once: the age of the Literary Life and the age of the Death of the Author. Nowadays, at the start of the new century, it transpires that reports of the death were greatly exaggerated. Literary biography remains in vogue. The bibliography that carries it forward is rolling and there is no sign of it turning into a pumpkin. Why is Cinderella so popular?

One obvious if superficial answer might be that literary biography is where literary people go who find the contemporary preoccupation with theory to be personally undernourishing and critically unenlightening; they would rather stay with the literary works themselves and with the lives, the minds and the times that produced them. Yet it is not only literary biography that is thriving; life-writing in general is a staple of mainstream publishing for which the appetite of the reading public seems insatiable. This commercial high profile is responding to an evident, if unfocused, need to look at other lives and understand them. Individual reasons for the popularity of biography range from prurient interest and hero worship to a, perhaps unrecognised, search for coherence and purpose in an age that is often disinclined either to accept institutional values or to respect traditional authority. The motives for this search usually include the desire for recognisable success, to which end the invention of a convincing identity is essential. Biographies offer models of how others live, face challenges and cope with change; they offer prime sites for studying ourselves. Curiously, this justification for biography as providing a model for living was felt most strongly when this literary genre first emerged in its recognisably modern form in the eighteenth century. The difference nowadays is that the model has changed: biography as a moral exemplum based upon Christian principles has been replaced in today’s celebrity culture by the demand for models of success provided by public personalities. Nonetheless, whatever the range of satisfactions readers seek in biography, life-writing offers detailed pictures of widely different ways of living and, amidst these perhaps, some clues to how an individual sense of identity might be shaped.

Literary biographies, as distinct from the past ‘Lives’ of politicians and military men, or the part ‘Lives’ of present-day footballers and pop idols, constitute a significant and, in several respects, a unique sub-genre. Literary biography often deals with subjects who stand apart from society’s norms and whose intertwined lives and writings offer a critique of the world the rest of us inhabit. Whether as an outsider like Shelley or as an insider like Dickens, the literary biographer’s subject tends to adopt an individualistic, critical view of the principles and practices of society which, on particular issues, may develop into outright opposition. The writer as rebel, the writer as exile, are familiar figures, particularly in the past two centuries.

Literary biography is unique, too, in that its subjects offer the prospect of access, however limited or illusory it may turn out to be, to the workings of the creative imagination. This prospect of gaining some insight into the mysteries of the artistic process is a seductive invitation to readers, one greatly enhanced by the intimacy between the biographer’s and the subject’s shared medium of words, their common interest in literary forms, and the particular closeness of fictional and historical narrative. When as often happens, an artistic affinity between biographer and biographee is inscribed in their relationship, the mystery of imaginative writing seems even closer. Novelists writing the ‘Lives’ of novelists (Mrs Gaskell on Charlotte Brontë; Peter Ackroyd on Dickens); poets writing the ‘Lives’ of poets (Andrew Motion on Philip Larkin; Elaine Feinstein on Ted Hughes); autobiographical writing in the form of poetry (Wordsworth) or fiction (Joyce) – all suggest specialist insights afforded by practitioners of the arts.

Literary biography also has an implicit appeal to readers as would-be authors, to the wish-fulfilment of being able to write poetry or fiction ourselves. Whether the writer’s life is seemingly mundane and ordinary, hemmed in by convention or prejudice, dogged by frustration and disappointment, or cut short by tragedy, we tend – despite the facts – to accept it as the essential condition of the creative being, romanticising the quality of the life into an inevitable pattern that reflects the works and which, because it does so, becomes a pattern at some level to be envied. If life could be lived vicariously, the writer’s life is the one we would choose; as biography, it offers a secondary life to share and enjoy alongside the secondary worlds created in the writer’s works.

Yet, despite the evident attractions of biography, it has become a truism to declare that biography has failed to establish any theoretical foundations upon which to build. In a period given to literary theory, Ellis (2000: 3) speaks of ‘the comparative dearth of analytic enquiry into biography’. Backscheider (1999: 2) quotes Ira Nadel’s remark on the absence of ‘a sustained theoretical discussion of biography incorporating some of the more probing and original speculations about language, structure, and discourse that have dominated post-structuralist thought’. She goes on to lament the poverty of criticism, the absence of a cultivated readership, the failure to engage even with the practical questions of selection, organisation or presentation, and indicates that readers of biography are too easily contented with reading for the life story. The implication is that biography is easy reading for lazy readers. D. J. Taylor, author of the biography Orwell: The Life, writing in The Guardian (8 November 2002), points to the unstable basis of the genre with a different emphasis: ‘Although several universities have recently established centres of biographical research,’ he says, ‘there is hardly such a thing as a theory of biography, merely an acknowledgement that each age tends to explore the form in a manner consistent with its preoccupations.’ This is uncontroversial if one compares pre- and post-Stracheyean biography, but it does not explain why, during the 1990s, there were four biographies of Jane Austen and three each of George Eliot and the Brontës – about all of whom we already know a great deal – let alone a dozen biographies this century of Shakespeare about whom we know next to nothing; or why, in a longer perspective, there have been over 200 ‘Lives’ of Lord Byron (Holmes, 1995: 18). This insistent rewriting of writers’ lives stems from more than commercial pressure. It indicates a genre where the life narrative can be explored from many different angles; where the revaluation and interpretation of existing and newly discovered evidence are fundamental to its history; and where biographers constantly respond to the challenge to represent the life in new artistic forms. Literary biography lies between history and fiction and has often been seen as the poor relation of both. As such it has attracted little theoretical interest from either side. Recent writing, however, has increasingly introduced elements of metabiography into studies of the genre (Miller, 2001; Sisman, 2001); and biographers have reflected in print upon the nature and principles of their work (Holmes, 1985; Holroyd, 2002; Lee, 2005). The issues they raise will constantly recur in the chapters which follow; and the origins of most of them are to be found in the mid-eighteenth century.

The Rise and Rise of Literary Biography

The modern history of literary biography has seen three phases of exceptional development. It was invented in the mid-eighteenth century by Samuel Johnson and James Boswell, reinvented by Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf at the start of the twentieth century, and today we are living in a period when the genre is showing a greater variety of formal innovations than ever before. Johnson and Boswell had their predecessors, notably Isaak Walton, who wrote the lives of John Donne (1640) and George Herbert (1670); and that most notorious of seventeenth-century life-writers, John Aubrey, whose Brief Lives (1667–1697) aimed to show that ‘the best of men are but men at best’. In his accounts of scholars and writers in a wide range of fields, he avoided general comments and empty praise in favour of specific, intimate and sometimes scandalous details. But Aubrey’s Brief Lives were just that – Milton is given eight pages, Shakespeare one and a half – and their contents are quirky, humorous, solemn and salacious by turns.

In the next two centuries, by contrast, biographies were to become long, substantial books devoted to a single subject; they aimed to incorporate the intimate details of a person’s life; and in doing so they ran up against fundamental issues such as verifiable facts versus likelihoods, personal privacy versus public knowledge, the biographer’s role in giving interpretations, opinions and judgements – all of which still exercise present-day biographers. No-one was more aware of these genre issues than Dr Johnson. Expressing his impatience with contemporary biographers who were content merely to log the chronology of their subject’s achievements, Johnson famously declared: ‘more knowledge may be gained of a man’s character, by a short conversation with one of his servants, than from a formal and studied narrative, begun with his pedigree, and ended with his funeral’ (Johnson, ‘On Biography’, The Rambler, No. 60). Johnson’s essay was published in the same year, 1750, as Fielding’s The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling. From the outset, the line between biography and fiction was a blurred one, as indicated by Fielding’s title, or by Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (1760–1767). And so it continued with Jane Eyre (1847), subtitled ‘An Autobiography’. Conversely, reading the opening chapter of Mrs Gaskell’s The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857) is like reading the start of one of her novels. The concurrent rise of the novel and biography meant that fictions incorporated quasi-documentary items like letters and diary entries more commonly found in biographies, whereas biographies presented scenes and people with the creative eye of the novelist. It is little wonder that boundary disputes should break out, or that biofictions like According to Queeney and Author, Author should develop the popularity they enjoy today. Nor is it surprising, given the aura that surrounds many writers, to find that recent literary biography often struggles to extricate itself not only from fiction but also from myth. The posthumous mythologizing of Sylvia Plath since her suicide in 1963, and Lucasta Miller’s demythologising in The Brontë Myth (2001), are two modern examples taken up in Chapter 4.

Fact, fiction or myth? Literary biography has long been a mixture of all three from its beginnings in Dr Johnson’s An Account of the Life of Mr. Richard Savage, Son of the Earl Rivers (1744), whose extended title attempts to mask by its assertiveness the uncertain status of its subject. Together with his Lives of the English Poets (1779–1781), in which the Life of Savage reappeared as an outsize component, Johnson is usually seen as the father of modern literary biography. The ‘son’, his successor and protégé in the next generation, was, of course, his own biographer James Boswell. Their approaches to biography were sharply different. Johnson’s style was to assimilate what information he could find about his subjects, to order it, interpret it, and weigh its significance and to produce a series of ‘Lives’ of generally modest proportions. (His Pope and Savage, the one through his eminence, the other for friendship, are longer exceptions to this rule.) Boswell’s view of biography was to let his subject speak for himself by quoting verbatim letters, conversations, stories and words of wit and wisdom, thus creating a ‘baggy’, loosely formed ‘Life’ of elephantine size. The contrast between the summary qualities of the ‘distilled life’ and the inclusiveness of the ‘comprehensive life’ punctuates the history of biography in various guises in succeeding centuries: in Strachey’s scornful rejection of ‘those two fat volumes’ that characterise Victorian biography and, nowadays, in the difference between, say, Carol Shields’s brief, personal life of Jane Austen (2001) and Park Honan’s fully documented Jane Austen: Her Life (rev. edn, 1997), which, its author claims in his Preface, ‘is acknowledged to be the most complete, realistic life’ of its subject.

Nineteenth-century biography generally favoured the Boswellian fullness without emulating his frankness. It reflected the decorous proprieties of its age and, as in the most celebrated and seminal literary biography of the period – Mrs Gaskell’s The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857) – eschewed ‘coarseness’ and tended to sanitise its subject with the fresh bloom of respectability. As Victorian certainties began to buckle, biography began to change, albeit slowly. In science, in Darwin’s account of natural selection; in society, in Marx’s analysis of cultural materialism; and in psychoanalysis, in Freud’s theory of the unconscious, there developed three powerful forces that subverted the conventional religious, societal and psychological views of the nature of man and the very concept of human identity. Biography, like poetry and fiction, underwent its modernist revolution, even if its Bloomsbury character made it less convincing and pervasive than its counterparts in the other arts. Nevertheless, Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians (1918) and Virginia Woolf’s preoccupation with biography in all her writings during the 1920s and 1930s together form the basis for what is usually called ‘the new biography’, a reappraisal of life-writing which, in its way, has been as influential as the works of its eighteenth-century originators.

Eminent Victorians made a great impact on its publication in May 1918. In a world disillusioned by war and distrustful of its leaders’ soundbites, Strachey’s wit and irony directed at four high-profile figures in Victorian society (Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Dr Arnold and General Gordon) hit the right sceptical and ‘slightly cynical’ note. His Preface has become a manifesto for later biographers both for its commitment to the value of individual lives and for its stylistic brevity and editorial selectivity. The first is seen in his remark that, ‘Human beings are too important to be treated as mere symptoms of the past. They have a value which is independent of any temporal processes – which is eternal and must be felt for its own sake’ (Strachey, 1986: 10). Unremarkable as such sentiments may now seem, to the immediate post-war generation they represented a necessary reaffirmation of individual worth. Stylistically, too, Strachey was radical. He argued that the biographer has to ‘adopt a subtler strategy’ than that of ‘scrupulous narration’. He has to be selective, coming at his subject obliquely, revealing character in unexpected ways, illuminating personality in a new light. ‘He will row out over that great ocean of material, and lower down into it, here and there, a little bucket, which will bring up to the light of day some characteristic specimen, from those far depths, to be examined with a careful curiosity’ (Strachey, 1986: 9). Strachey’s style of ‘short condensed biography’ returned life-writing to the Johnsonian form in that it avoided both the dead weight of heavy documentation and the light weight of facile, conventional panegyric. But Strachey’s subjects, unlike Johnson’s, were set up as targets, representative of false, misleading or hypocritical values of the Victorian age, not held up to us as individuals whose lives should be a lesson to us all.

Virginia Woolf’s contribution to ‘The New Biography’ (the title of her first essay on the subject in 1927) was of a quite different nature. Biography permeates her work, obliquely and profoundly in her novels, especially To The Lighthouse, humorously in Orlando and Flush, directly in her essays and in her Life of Roger Fry, incidentally in her letters and diaries, and movingly in her autobiographical writings collected under the title Moments of Being, which Hermione Lee describes as ‘an evolving narrative about the process of “life-writing”’ (Lee, 2002: xiii). The issues that preoccupy Woolf are fundamental to biography: the relationships between fiction and non-fiction, art and craft, documentary and invention, truth in fact and truth in art. The issues remain ‘live’, not only, as noted above, in current thinking about biography, but also in the innovations in the form that have appeared in the past two decades. For example, the seven controversial Interludes in Peter Ackroyd’s Dickens (1999), which challenge the generic boundary between fact and fiction; the ten Interchapters in D. J. Taylor’s Orwell: The Life (2004), where the biographer steps out of the time-frame and takes a sideways glance at his subject; and, most radical of all (see below in Chapter 12), in Jonathan Coe’s biography of B. S. Johnson, Like a Fiery Elephant (2004), which, mirroring his subject’s work, is fragmentary in structure and confessional in tone, ‘more a dossier than a conventional literary biography’, as he warns us in his Introduction. Biography is not only thriving but is thoughtfully interrogating itself; and, during its long history, two figures stand out as maintaining a continuing relevance: Dr Johnson and Virginia Woolf.

Dr Johnson: Biographer, Theorist and Subject

The strange case of Richard Savage is an unlikely subject for the first literary biography. Savage was a minor poet, a convicted murderer who received a royal pardon, a vagrant who wandered the streets of London at night, whose life began with uncertain parentage and ended in Newgate Gaol in Bristol. The relationship between Richard Savage and Samuel Johnson which resulted in the latter’s Life of Savage has puzzled people since its first publication in 1744. The identity of the subject and the role of the biographer lie at the heart of the story. The mystery that encompasses them unites biography then with biography now in Richard Holmes’s modern masterpiece, Dr. Johnson and Mr. Savage, a title whose Stevensonian echo captures the unusual intimacy of the biographer and his subject.

Literary biography thus got off to a controversial start. Questions abounded:

What relationship lay behind the

Life of Savage

in the time between Samuel Johnson’s arrival in London in 1737 and Richard Savage’s death in 1743?

Why would a morally scrupulous man like Johnson become a close friend and biographer of an apparently unstable, feckless character such as Savage?

What are we to believe about the selection and interpretation of the ‘facts’ of Savage’s life in Johnson’s biography?

What does the account reveal about the biographer as well as his subject? About his judgements? About his qualities as a writer?

The first two questions concern the biographer/biographee relationship and, in particular, the benefits and disadvantages of friendship between the two, a subject on which Johnson was characteristically blunt: ‘If the biographer writes from personal knowledge … there is a danger lest his interest, his fear, his gratitude, or his tenderness, overpower his fidelity and tempt him to conceal, if not to invent’ (The Rambler, No. 60). The second two questions concern Johnson’s skill as a biographer, his handling of his materials and his strategies in turning them into a ‘Life’. Three substantive issues arise in reading his Life of Savage, each one a particular puzzle and each having a bearing upon these wider questions.

First, who was Johnson’s subject? Was he a nobleman or an imposter? His mother should know – but was she his mother and was she honest? Richard Savage claimed throughout his life that he was the illegitimate son of Lady Macclesfield and Earl Rivers, born in Holborn on 10 January 1698, but his ‘mother’ never acknowledged his claim to be her son and regarded him as a blackmailing imposter or a deluded crank. Johnson, as he makes clear in his full title and in his advocacy throughout the ‘Life’, supported Savage’s claim. Whether he entertained any doubts about its truth remains open to question. Secondly, how does Johnson deal with the central incident in Savage’s history – his conviction for the fatal stabbing of one James Sinclair in a coffee-house brawl on 20 November 1727? Was it murder or self-defence? In a forensic analysis of Johnson’s account, Richard Holmes lays bare the ways in which Johnson defends Savage by ‘bending his own rules of biographical realism’ in the biased presentation of the courtroom drama, in the fictional projection of Savage’s voice, and in the caricaturing of the presiding Judge Page (Holmes, 1994: 100–132). Here, too, the ‘truth’ hangs in suspension between fact and fiction, between the incomplete documentary evidence and the ‘adversarial skill’ Johnson shows in mounting a defence of his friend. Thirdly, what conclusions does Johnson draw in his final setpiece where, if he is to be true to his own principles, his aim is for fair and balanced judgement? Certainly, Johnson catalogues eloquently both his subject’s vices and shortcomings and his virtues and abilities. The balance is evident and reflected in his carefully modulated sentences; but so seductive are their disarming tone and urbane style that Savage’s faults seem merely the endearing weaknesses of a mercurial character for whom we instinctively make allowances. Johnson’s precarious balance is also there in the psychological ‘twist in the tail’ at the very end of his biography. Richard Holmes argues that this ‘Life’ has, in effect, two alternative endings, the final paragraph being ‘Added’, the word Johnson wrote against it when preparing the second edition. This later ending condemns Savage’s life as showing that ‘nothing will supply the want of prudence, and that negligence and irregularity, long continued, will make knowledge useless, wit ridiculous, and genius contemptible.’ By contrast, the original ending which now forms the penultimate paragraph advocates empathy rather than condemnation: ‘nor will any wise man presume to say, “Had I been in Savage’s condition, I should have lived or written better than Savage”’. Holmes sees this as Johnson’s real conclusion, and the later ending as a ‘placatory afterthought; a conciliatory gesture to the forces of social opinion’ (Holmes, 1994: 226–227).

The ambivalence of the ending is symptomatic of the unstable life upon which the whole biography is built. In Johnson’s conduct of the case for the defence, we are simultaneously aware that, however brilliantly it is advocated, his is a tendentious account, a narrative in which the search for truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth is compromised through a combination of personal loyalty and rhetorical skill. Desmond McCarthy’s much-quoted description of the biographer as ‘an artist on oath’ may be admirable in aspiration but, as Johnson’s Savage shows, it papers over the cracks between the truth of art and the truth of fact.

Yet, Johnson believed, in theory, in telling the whole truth, as the ending of his essay ‘On Biography’ (The Rambler, No. 60) shows. In practice, however, Boswell detected some contradiction, or what he tactfully calls Johnson’s ‘varying from himself in talk’. On one occasion, Johnson argued that mention of Addison’s and Parnell’s excessive drinking should be censored since it would encourage others to do the same; on another, he argued that such an example would act as an ‘instructive caution’ (Boswell, 1791/1949, II: 115). There is ambivalence, too, in Johnson’s view, quoted above, of the effects of friendship and ‘personal knowledge’ in the biographer/ biographee relationship, both in writing the ‘Life’ of his friend Savage and in encouraging the writing of his own ‘Life’ by his friend Boswell. The essay in The Rambler, No. 60 is, nevertheless, Johnson’s principal statement. Its essential premise is the democratisation of biography: ‘I have often thought that there is rarely passed a life of which a judicious and faithful narrative would not be useful’. The motive is educational: ‘no species of writing seems more worthy of cultivation than biography, since none can be more delightful or more useful … or more widely diffuse instruction’. The means should be to ‘display the minute details of daily life’ which ‘lead the thoughts into domestic privacies’, rather than dwelling on incidents that ‘produce vulgar greatness’. Johnson’s educative principle is that people learn from other people’s experiences, from particulars not from generalities, from life histories in which everyone can imaginatively recognise shared hopes and problems, not from ‘histories of the downfall of kingdoms and revolutions of empires’. Johnson’s two later essays in The Idler, Nos. 84 and 102 provide a gloss upon these principles. The first stresses the usefulness of biography as a pragmatic guide in daily life and raises the issues of accuracy and belief in autobiography. The second promotes the idea of authors, rather than soldiers or statesmen, as biographical subjects, and ends with a typical Johnsonian side-swipe at his favourite target, the patron. Johnson was able to put this idea of literary biography into practice in his Lives of the English Poets in which, in the more substantial accounts of major writers such as Pope, Dryden, Swift and Milton (as well as in the recycled Savage), he shows how, for the first time, biography can explore the relationships between the writer, his works and the times. In the essays, in the ‘Lives’, and especially in his Life of Savage, Johnson did more than anyone to establish biography as a literary genre. He rescued it from the fate of ‘tedious panegyric’; he demonstrated that life-writing is based upon narrative skill, on the deployment of data and evidence, and on the (re)creation of historical scenes; and, despite his all-too-human struggle to reconcile theory and practice, Johnson’s belief in the ethical basis of biography, grounded in human sympathy and backed by moral principles, is never in doubt.

* * *

Boswell’s Johnson is a quite different figure from the implied image of the author of the Life of Savage. Young Sam Johnson, newly arrived from the provinces, shows a puzzling if consistent loyalty, a sense of justice that verges on outrage, and a degree of credulity and romanticism over Savage’s misfortunes. His attitude has often provoked the question of how much he saw his own early struggles mirrored in the life of his friend. Did Johnson, the biographer, unwittingly write something of his own autobiography? By contrast, the Johnson whom Boswell knew, and the one we have all inherited from his biography, is a mature, successful man in his mid-fifties; the revered Tory of the clubs and dinner tables, the sententious sage, confident in argument and universally respected as poet, essayist, lexicographer – the great man of letters of his age. How did Boswell create this portrait?

There are many ways in which Boswell, while firmly anchored in his time, remains our contemporary as a biographer. His procedure in compiling The Life of Dr. Johnson was new to the art of biography, and four of his techniques, with modifications, remain part of the biographer’s armoury today. The summaries which follow draw upon Adam Sisman’s invaluable and entertaining book, Boswell’s Presumptuous Task (2001).

First, Boswell kept a journal as an aide-mémoire