45,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

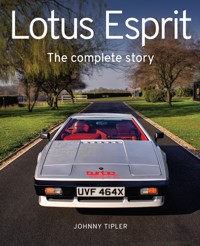

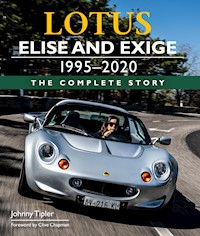

From the Mark 1 in 1948 to the World's most powerful electric hypercar – the Evija – in 2021, the story of the Lotus marque encompasses ongoing technical innovation on road and track. With seventy-four F1 Grand Prix wins, six Drivers' and seven Constructors' F1 World Championships chalked up over seven hectic decades, Lotus consolidated its reputation in racing while at the same time creating some of the World's most stylish and desirable sportscars and Grand Tourers, in-house as well as for global automotive clients via its Lotus Engineering consultancy. With over 380 photographs, this book includes: the origins of the business, creating Austin 7-based competition cars; the metamorphosis from sports-racing cars to F1 – and seven World titles; factory relocations, from Hornsey to Cheshunt to Hethel; the road cars: the Elite, Elan, Europa, Excel, Esprit, Elise, Exige and Evora; how sponsorship transformed traditional British Racing Green into Gold Leaf and JPS livery. There are also interviews with key Lotus personnel and drivers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

LOTUS

THE COMPLETE STORY

JPS Lotus 91 and the fabulous Gerry Judah loop-the-loop aerial raceway, featuring Lotus F1 and Tasman racing cars, in the grounds of Goodwood House at the 2012 Festival of Speed.

LOTUS

THE COMPLETE STORY

JOHNNY TIPLER

FOREWORD BY MIKE KIMBERLEY

First published in 2022 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2022

© Johnny Tipler 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 71984 006 7

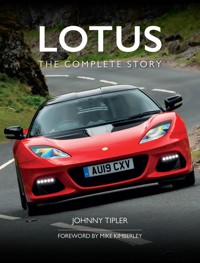

Front cover: The Evora was in production from 2009 until 2021. The GT430 Sport model is in action here at Cheddar Gorge.

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

Picture credits

Jeff Bloxham

Fred Bushell Archives

Laurie Caddell

Alex Denham

Roger Dixon

Stephanie Ewen

Antony Fraser

Sarah Hall

Laura Hampton

Kate Hunt

Mike Kimberley

Théodora Lecrinier

Esta-Jane Middling

Peter Mills

Guy Munday

Kenneth Olausson

Jason Parnell

Abi Powell

William Taylor

Wim Te Riet

Johnny Tipler

Joerg Uhr

Arjan Van Gemerden

Sonja Verducci

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Mike Kimberley

Timeline

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 THE HORNSEY YEARS, 1952–60

CHAPTER 2 THE CHESHUNT YEARS, 1960–6

CHAPTER 3 THE HETHEL YEARS, 1966–83

CHAPTER 4 FROM GM TO BUGATTI, 1983–96

CHAPTER 5 FROM PROTON TO GEELY, 1996–2021

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly, I’m thrilled to have the foreword written by Mike Kimberley, former Lotus MD and CEO who steered the company through thick and thin, and masterminded the design and production of several key models.

Next up, I want to thank Alastair Florance, Lotus press officer who arranged interviews with key personnel at the factory and provided several press cars over the years for me to evaluate. I’m also indebted to former marketing executive Caroline Parker, who took me on international Lotus assignments, enabling driving experiences in a host of exotic locations.

Photos come from a number of sources, starting with William Taylor’s comprehensive Coterie archive; former Lotus in-house photographer Jason Parnell, who joined me on many trips; my habitual snapping comrade Antony Fraser – who also provided the book’s cover shot – plus some of my own shots; and I’m also especially grateful to Kenneth Olausson, Stephanie Ewen, Sarah Hall, Alex Denham, Laura Hampton, Elisa Artioli, Peter Mills, Jeff Bloxham and Rémi Dargegen for supplying images. Original artworks gracing these pages were produced especially for the book by Caroline Llong, Kate Hunt, Sonja Verducci, Abi Powell and Esta-Jane Middling, for which many thanks.

Elisa Artioli is very active with her own car, in this instance leading a posse of Lotuses up the Stelvio Pass in 2020. The profile shot reveals the exquisite lines and detailing of her namesake, the Julian Thompson-styled Series 1 Elise.

Clive Chapman inherited many of the cars built and run in their heyday by Team Lotus, and together with a band of stalwart engineers and mechanics, he oversees their renaissance at Classic Team Lotus.

I’m delighted to include interviews and quotes I’ve recorded over the years with deities of the Lotus persuasion, including Clive Chapman, Emerson Fittipaldi, Mario Andretti, Bob Dance, John Miles, Stirling Moss, Jackie Oliver, Andy Middlehurst, Peter Brand, Brian Luff, Jim Endruweit, Peter Warr, Chris Dinnage, Kevin Smith and Malcolm Ricketts. Stories and images reflect events I’ve attended, road trips I’ve done, and venues visited over the years, including Silverstone Classic, Goodwood Revival and Festival of Speed, the Monte Carlo Rallye Historique, Porto Historic Grand Prix, Spa Six Hours, Algarve Historic Grand Prix, Zandvoort Historic Grand Prix, Nürburgring Old Timer, Solitude Revival, Tour Auto, several LOG events in the USA, the Lotus Festival, Barber Vintage Motorsport Museum, Spring Mountain Race School, Monaco Historic Grand Prix, Le Mans Classic, Ennstal Classic Rally, the RAC Rally, Jim Clark Revival at Hockenheim…

It’s not been without surprises, too: midway through composing this tome, the daughter and son-in-law of Lotus’s erstwhile company secretary and head of finance, Fred Bushell – Erica and Nick Copeman – gave me access to Fred’s memoirs that cover the period from 1945 to 1972, and these provide a fascinating account of Lotus’s early years – cut short at 1972 when Fred became too ill to continue writing, around 2008. Erica and Nick also furnished me with photos from Fred’s archives.

FOREWORDBY MIKE KIMBERLEY

I’m delighted to write the foreword to Johnny Tipler’s new Lotus history book, as my rapid career progress was thanks to Colin Chapman, and largely associated with the marque. As Johnny affirms, the history of Lotus is a saga of technical innovation and aesthetic masterpieces played out over seven hectic decades. From its formative days as the hobby of an ambitious Colin Chapman in 1948 and the founding of the company in 1952, the marque went on to flourish at its North London base as the producer of aerodynamically sensational sports racing cars. Team Lotus’s competition successes stimulated sales, and the innovative Elite attracted customers seeking the ultimate in road-going sports cars.

Mike Kimberley, engineering director, managing director and CEO of Group Lotus, and co-founder with Colin Chapman of Lotus Engineering.

For much of its existence, Lotus has been synonymous with top-line racing cars as well as class-leading sports cars, and this interaction is reflected in the history of the company and its racing associations. The Ford Lotus Cortina of 1963 was a perfect example of the crossover between road and race cars, a symbiosis that suited both manufacturers perfectly. Lotus has always been about innovation. Having relocated to its new factory at Cheshunt in 1959, it led a revolution in Grand Prix racing and sports car racing, sweeping the board with lightweight mid-engined chassis powered by small-capacity engines. Together with Scottish driver Jim Clark, Chapman won the F1 world title for drivers and constructors in 1963, Clark helming the monocoque Type 25. Two years later, Jim and Team Lotus won the F1 championship again, this time in a Type 33, as well as the Indy 500 with the Type 38. Meanwhile, the Cheshunt factory was producing the Elan – favourite of the trendy Kings Road fraternity, while the Seven proved a winner for ‘down-to-earth’ enthusiast drivers.

Another major move came in 1966, this time to our present site at Hethel in central Norfolk, into a brand-new factory on the airfield site with its own test track and wartime buildings to house the racing activities. A tie-up with Renault spawned the mid-engined Europa, with the +2 Elan launching the following year. Team Lotus won the F1 world title again in 1968, Graham Hill lifting the crown as well as sharing Colin’s burden of grief following Clark’s death in an F2 race earlier in the year.

Chapman the indomitable innovator initiated big-time commercial sponsorship in 1968, presenting Lotus F1 racing cars in the livery of the Gold Leaf cigarette brand for John Player & Sons.

A pair of Elevens and a Mk 9 entered for Plateau 3 at the 2018 Le Mans Classic meeting.

Darling of the young and trendy, the Elan in coupé format lingers outside the Hilton Hotel in London’s Park Lane.

I joined Lotus from Jaguar in 1969, and my first project was the Europa Twin-Cam in 1971, and big-valve in 1972. In 1970, Team Lotus’s driver Jochen Rindt won the World Championship driving the Types 49 and 72, though he lost his life at Monza before the season ended. For 1972, Team Lotus racing livery switched to the iconic JPS John Player Special brand, and our driver Emerson Fittipaldi won the world title in the black and gold Type 72. Joined by Ronnie Peterson for 1973, the pair won the World Constructors’ Championship for Lotus in 1973.

Lotus was on a roll, both on road and track, and Colin Chapman took the road car range upmarket into the grand touring segment. As chief engineer and then director of Lotus Cars, I was responsible for the second-generation Elite in 1974, followed by the Eclat and then the introduction of the mid-engined Esprit in 1976. Having invested heavily in state-of-the-art composite technology, vehicle dynamics, and in the manufacture and development of our own all-aluminium, 4-valves-per-cylinder, high-performance and fuel-efficient engines, as well as cascading technology from F1 racing to road cars, Colin and I decided in 1977 to create Lotus Engineering as an advanced engineering, high-tech consultancy business to broaden the group business base.

The first project was initiated in January 1977, with the successful Talbot Sunbeam Lotus. The competition version won the RAC rally with Henri Toivonen in 1980 and the World Rally Championship in 1981. This project was followed over time by complete new vehicles, such as the DeLorean DMC12, and advanced-technology projects for most of the world’s automotive firms, including Chrysler, Toyota, General Motors, Volvo, PSA, Nissan, Hyundai, Kia, Aston Martin, Suzuki, Austin-Rover, Isuzu and Ford, to name just a few.

Pictured at Le Mans Classic, a Type 47 comes into the pits for a driver change. The 47 was based on the Europa, fitted with the 165bhp 1594cc Lotus-Ford twin-cam, with Girling disc brakes and Lotus four-spoke centre-lock wheels.

On track, Team Lotus then leapfrogged the F1 firmament, using the underside of the car to generate ‘ground effect’ downforce. This was followed by computer-controlled ‘active suspension’ – both Chapman-driven Lotus firsts. Driving the JPS Type 79, Mario Andretti and team mate Ronnie Peterson proved invincible in 1978. Mario and Lotus took the world title at Monza, though we tragically lost Ronnie during a hospital operation to reset his broken legs, caused by an accident during an unsafe start by the race official. Colin and I were in attendance, and we were both in shock.

The Talbot Sunbeam Lotus, of which we built over 2,000 examples between 1979 and 1981, was a homologated rally car for the road, a reprise of the Lotus Cortina. By now, Colin had already expanded into the world of motor yachts, acquiring Moonraker Marine in 1971, and we were seriously involved in the development of our own air-cooled engine for microlight aircraft when, tragically, he suffered a heart attack and died on 16 December 1982, aged just fifty-four.

Inevitably, this led to the dawning of a new era, with me becoming MD of Group Lotus, AMEX bank withdrawing, and our share price hitting rock-bottom on the FTSE! With the world in unprecedented economic recession, Lotus Cars was seriously affected, while, as planned, the Lotus Engineering technology business was growing hand over fist. Group Lotus finances were extremely critical but, thanks to our close relationship and the existing collaboration we enjoyed with Toyota, we were able to count on substantial and timely financial support in February and May 1983, which saved the company.

From late 1983 to the end of 1985, Group Lotus Plc was owned by five investors, including BCA, Toyota and JCB. During that time, we grew the engineering consultancy business significantly while lacking the funding for new Lotus models, including the Toyota-based Elan M90.

GM acquired the Group in January 1986, investing heavily in re-facilitating the car company and belatedly launching the M100 GM-based Elan in 1989. Under Jack Smith and Bob Eaton at GME, Lotus was encouraged to prosper, enabling the acquisition of the 800-acre Millbrook International Proving Ground for Lotus Engineering, and the image-building, ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing’ joint venture – the Lotus Carlton-Omega, a four-door, four-seater saloon capable of circa 180mph (290km/h), which caused a sensation both in the media and in parliament!

Lotus was sold, however, in August 1993, to Romano Artioli of Bugatti. During that turbulent period, while I was personally working in Asia Pacific as an EVP of General Motors Overseas Corporation from January 1992, and then president and CEO of Automobili Lamborghini SpA in Sant’Agata Bolognese through 1996, Group Lotus was again changing owners.

The Type 100 second-generation Elan was unveiled at the 1989 Earls Court Show. To comply with US federal regulations, the 1588cc Isuzu engine was turbocharged for the more numerous Elan SE model.

Meanwhile, at the privately owned Team Lotus, team manager Peter Warr ran the F1 racing stable through to 1990. During that period, lead drivers were Nigel Mansell, Elio de Angelis and Ayrton Senna, with John Player Special sponsorship passing on to Camel cigarettes – from black and gold to yellow. I recall being at the 1987 Detroit Grand Prix with our brilliant engineering MD Peter Wright when Senna won with the active suspension Lotus 99T: a fantastic performance, which left him absolutely drained. I had to help Ayrton across the track to collect the trophy and carry it back to the Lotus enclave because he was so exhausted and dehydrated. It was Team Lotus’s seventy-ninth Grand Prix victory and, sadly, its last. In 1991, Peter Wright left Lotus Engineering, and together with Peter Collins, took over the helm of Team Lotus until 1994, when its sponsorship ran out.

In 1996, with ownership of Group Lotus passing to state-owned DRB-HICOM, who also owned Malaysian car maker Proton, out-going Bugatti owner Romano Artioli had reintroduced the M100 Elan as the S2 in June 1994, followed by the V8 Esprit in Spring 1996, and then the car that returned Lotus to the forefront of the entry-level sports car market, the Type 111 Elise, on sale in October 1996.

Ownership of Group Lotus PLC was then divested from DRB-HICOM to Proton Holdings Berhad in 1997. While Lotus was under Proton ownership, I was invited in late 2005 to join a number of boards, one being Group Lotus. After persuading the shareholders to allow Lotus to be rejuvenated, we created and launched in 2008 the company’s first new model for thirteen years, the Evora, a 32-month ‘clean-sheet-to-sale’, dedicated and committed Lotus team ‘can-do DNA’ achievement; we rebuilt the Lotus Engineering consultancy business globally with EV and new technology while returning the group to financial stability.

The jagged pinnacles of Montserrat form a backdrop to our Catalonian road trip with the Elise S, winding through the Muntanya national park and up to the lofty 8,200ft (2,500m) monastic pilgrimage site.

Launched in 2009, the Type 122 Evora was configured as a 2+2, but could be ordered without the rear seats as a two-seat coupé. An automatic version was also available, the IPS (Intelligent Precision Shift). Looking cool in black, this car is participating in a press launch in Provence.

Another Mike Kimberley legacy: the Exige 260 Cup, supreme on the 2009 Dutch Spring Run, meandering through gorgeous landscapes bookmarked by windmills and canals between Amersfoort, Kampen and Bad Bentheim.

Pictured outside the former Team Lotus and Classic Team Lotus World War II premises off Potash Lane, the heritage edition Exige 430 Cup of 2018 echoes the black-and-gold JPS-liveried 1978 World Championship-winning Type 79.

Vertiginous view: an example of every Lotus F1 car ever built, assembled on the grid at Snetterton during the 2010 Lotus Festival, organized by Clive Chapman.

Sadly, a serious accident forced my early retirement in July 2009. Lotus subsequently entered a period of instability with a resultant lack of business plan continuity and consistent strategy.

A corner was turned when, in 2017, the Chinese global automotive company Geely gained a 51 per cent controlling share of Lotus, with 49 per cent owned by Etika Automotive, a Malaysian conglomerate, giving the company a new lease of life with exciting long-term prospects, including rebuilding Lotus Engineering as an innovative and creative advanced technology consultancy business.

With new models in the pipeline, in 2019, the world’s most powerful electric hypercar was unveiled: the 2,000hp Evija, representing a new flagship model for Lotus and heralding an extensive brand-new range of cars, starting with the Type 131 range, which is set to launch Lotus in 2022. On road and track, Lotus cars have always projected their peerless DNA, evident in a host of unique driver-vehicle dynamic sensory attributes, and the T131 will undoubtedly fulfil those criteria, being manifestly a real Lotus.

So much for history: the future looks very bright indeed for Lotus at Hethel, with a state-of-the-art new factory, equipment, facilities, advanced new models and technology. Colin Chapman would be proud.

Mike Kimberley CEng, FIMechE, FRSA,FIMI, FIEngD, Harvard alumnusFormer managing director and chief executive officer of Group Lotus plc

TIMELINE

1947

Mk 1: Colin Chapman’s first car; one made.

1949

Mk 2: trials special, later used for racing; one made.

1951

Mk 3: racing car built to 750 Formula; two made.

1952

Mk 4: road-going and sprint car; one made.Lotus Engineering formed, based in Tottenham Lane, Hornsey.Mk 5: not made.

1953–5

Mk 6: first production sports car; 110 made.

1954

Mk 8: sports racing car; seven made.

1955

Mk 9: sports racing car; thirty made.First Lotus appearance at Le Mans 24-Hours.Mk 10: sports racing car; six made.

1956–8

Eleven: sports racing car. Class win and Index of Performance victory at Le Mans in 1957;166 Series 1 and 104 Series 2 made.

1957

Mk 12: first single-seater Lotus, a Formula 2 car; twelve made.

1957–61

Lotus Cars Ltd formed. Lotus Engineering Co.Ltd constructs racing cars, Team Lotus Ltd is factory racing team.Lotus moves to Cheshunt factory in June 1959.Type 14 Elite: sports GT model; 281 Series 1 and 749 Series 2 made.

1957–3

Seven: production sports car; 243 Series 1 made, 1,310 Series 2, 340 Series 3, 13 Series 3SS and 625 Series 4.

1958–60

Type 15: sports racing car; twenty-seven made.Type 16: Formula 1/Formula 2 racing car; eight made.

1959

Type 17: sports racing car; twenty-three made.

1959–60

Type 18: rear-engined single-seater for Formula 1, 2, and Junior; 120 Formula Junior and thirty F1 made.

1960–1

Type 19 Monte Carlo: rear-engined sports racing car; seventeen made.

1961

Type 20: Formula Junior racing car; 118 made.Type 20B: Formule Libre or Formula B; 118 made.Type 21: Formula 1 racing car; eleven made.

1962

Type 22: Formula Junior racing car; seventy-seven made.Type 23 and 23B: sports racing car; 131 made.Type 24: Formula 1 car; fifteen made.Type 25: Formula 1 car; seven made.Type 26: Elan 1500 and 1600, production sports car; 848 Series 1 made.

1963

Type 27: Formula Junior; thirty-five made.Jim Clark and Team Lotus are 1963 F1 World Champions.Type 28 Lotus-Cortina: production saloon car; 2,894 made.Type 29: Indianapolis racing car; three made.

1964

Type 26R Elan: sports racing car; ninety-seven made.Jim Clark is British Saloon Car champion.Type 30: sports racing car; thirty-three made.Type 31: Formula 3 car; twelve made.Type 32: Formula 2/Formula B; twelve made.Type 32B: Tasman series racer; one made.Type 33: Formula 1 car; six made.Jim Clark and Team Lotus are World Champions.Type 34: Indianapolis racer; three made.Type 26: Elan Series 2; 848 made.

1965

Type 35: Formula 2/Formula 3/Formula B car; twenty-two made.John Whitmore is European Touring Car champion in Alan Mann Lotus Cortina.Type 36: Elan S3 Coupé; 1,200 made.Type 37: Seven-based sports racing car; one made.Type 38: Indianapolis racing car: Jim Clark victorious; ten made.Type 39: Formula 1/Tasman racer; one made.Type 40: sports racing car; three made.

1966

Type 41: Formula 3 car; sixty-one made.Type 42 and 42F: Indycar; two made.Type 43: Formula 1 car; two made.Type 44: Formula 2, run by Charles Lucas Team Lotus; three made.Type 45: Series 3 Elan soft-top; 1,450 made.Type 46 Europa: production coupé; 644 made.Type 47: sports GT, based on Europa; seventy-one made.

1967

Types 41, 41B and 41X: Formula 2, 3 and B; sixty-one made.Type 42: Indycar; two made.Type 48: Formula 2 car; four made.Type 49: Formula 1 and Tasman; twelve made.Team Lotus adopts Gold Leaf livery of John Player & Sons.Type 50: Elan +2; 2,000 made.+2S released 1969; 1,000 built. +2S 130 released 1971; 2,088 made.Type 51: Formula Ford; 218 made.

1968

Series 4 Elan hard- and soft-tops; 1,450 made.Type 56: gas turbine Indycar. Type 56B resurfaces in F1 in 1970; four made.Type 51: Formula Ford; 200 made.Type 58: Formula 2/Tasman car; one made.

1969–70

Type 59/59F: Formulae 2, 3, Formula Ford; forty-two made.Type 59B: Formula 2 and Formula B single-seater; ten made.Type 61: Formula Ford; 248 made.Type 62: sports prototype racer; two made.Type 63: 4×4 Formula 1 car; two made.Type 64: STP-sponsored Indycar; four made.Type 65: Europa Series 2, Federal spec; 865 made.

1970–1

Type 69/69F: Formula 2, 3 and Formula Ford; ten F2 cars made, fifty-five F3 cars, fifty-five Formula Ford.Type 70: Formula 5000 and Formula A; ten made.Type 72: F1 car in Gold Leaf and JPS livery; nine made. World Drivers’ Championship winner in 1970 and 1972 and Constructors’ Cup in 1973.Chapman buys Moonraker Motor Yachts.

1972

Type 73: Formula 3 car; two made.Closure of Lotus Racing –- no more customer cars.

1973

Type 74: Formula 2 car; three made. Type 74 is also Europa Twin-Cam; 4,710 made.

1974

Type 75: Elite 2+2 GT, 1973cc 907 twin-cam engine; 2,398 made.Type 76: Formula 1 car; two made.

1975

Type 76: Eclat; 1,299 cars made.Type 79: Esprit GT; 864 made.

1976

Type 77: Formula 1 car; three made.Mike Kimberley becomes MD of Lotus Cars.

1977–8

Type 78: First Formula 1 ground effect car, based on design work by Peter Wright and Tony Rudd.Negative lift is generated by channelling air through venturi in the side pods; four cars made.Type 76 is also Eclat Sprint designation.Lotus Engineering consultancy business initiated.

1978–9

Type 79: Esprit Series 2; 1,068 made.Type 79 designation shared Formula 1 car, in which Mario Andretti and Team Lotus are F1 World Champions; six made.

1979

Type 80: Formula 1 car, Martini sponsorship; two made.

1980–1

Type 81 and 81B: Formula 1 car, Essex Petroleum livery; three made.Type 81 is also designation for Talbot Sunbeam Lotus rally car; 2,318 made. Winner of 1980 Lombard RAC rally and 1981 World Rally Championship Manufacturers’ title.Type 82: Esprit Turbo; 1,274 made. Esprit S2.2; ninety-three made.Type 83: Elite Series 2 and S2.2; 133 made.Type 84: Eclat Series 2 and S2.2; 223 made.Type 86: Twin-chassis Formula 1 car; one made.Type 85: Esprit Series 3; 767 made. Restyled Esprit unveiled in 1987; 286 made.Type 87 and 87B: Formula 1 car; three made.

1982

Type 89: Eclat-Excel production GT car; 872 made.Type 91 Formula 1 car; two made.Colin Chapman dies, 16 December 1982, aged fifty-four. Peter Warr now runs Team Lotus.

1983

Mike Kimberley is group managing director.Type 92: Formula 1 car; two made. Computerized hydraulic ‘active ride’ suspension unveiled.Type 93T: 1.5-litre twin-turbo Renault EF1 V6; two made.Type 94T: Formula 1 car; three made.

1984

Type 95T: Formula 1 car; four made.Type 96T: Indycar project; one made.

1985

Type 97T: Formula 1; four made.Type 89: Excel SE and SA; 1,300 made.

1986

Group Lotus passes to General Motors andToyota;Toyota defers to GM after four months.Type 98T: Formula 1; four made.Turbo Esprit HC and HPCI Federal edition; 2,819 made.

1987

Type 99T: Formula 1 car, Camel sponsorship, with active suspension; six made.Group Lotus takes over Millbrook Proving Ground for Lotus Engineering.Esprit Turbo; 250 made.

1988

Type 100T: Formula 1 car; four made.

1989

Type 100: M100 Elan and Elan SE; 129 and 3,167 made.Turbocharged Federal version: 559 made.Esprit Turbo SE; 1,608 cars made.Type 101: Formula 1; four made.Peter Warr leaves Team Lotus.

1990

Type 102: Formula 1 car; five made.Type 104: Lotus Carlton-Omega; 950 made.Type 105: Esprit SE; twenty-two made.Type 106: Esprit X180R SCCA race car; three made.

1991

Type 102B: Formula 1 car; three made.

1992

Type 107: Formula 1; four made.Clive Chapman sets up Classic Team Lotus.Type 108: Chris Boardman-inspired pursuit bicycle; fifteen made.Esprit Sport 300; sixty-five made.

1993

GM sells Group Lotus to Romano Artioli’s ACBN Holdings.Type 107B: Formula 1 car.Esprit S4; 624 made.

1994

Type 109: Formula 1 car; three made.Team Lotus closes.Turbocharged Elan S2; 800 made.Type 110: time trial bicycle.Esprit S4S; 361 made.

1995

Esprit GT2 race car for Global Endurance series; three made.

1996

Type 111: Elise S1; 8,600 made.Malaysian DRB-HICOM Group acquires major stake in Group Lotus from Artioli.Esprit GT3; 196 made.Esprit V8; 550 made.

1997

Type 115: Elise-based GT1 racing car; eight made.Type 114: Esprit GT1 race car; three made.Twin-turbo Esprit V8GT; 204 made.Proton Holdings Berhad takes 80 per cent control of Group Lotus – operating as Lotus Cars, Lotus Engineering and Lotus Sport.

1998

Lotus’s fiftieth anniversary celebrations.Elise Sport 135; eighty-five made.Elise Sport 190; forty-eight made.Esprit Sport 350; fifty-eight made.Esprit V8SE; 600 made.

1999

Elise 111S; 1,487 made.Type 49; 134 made.340R concept car; 340 made.Motorsport Elise unveiled.Type 118: M250 prototype; two made.

2000

Autobytel Lotus Sport Elise; sixty-six made.GM VX220 Speedster.Elise Sport 160; 319 made.Type 111 Exige S1; 604 made.

2001

Elise S2; 4,500 made.

2002

Elise Type 111S; 2,000 made.Type 82, Esprit Final Edition.

2003

Sport Elise 135R; 123 made.Type 119: soapbox contests Goodwood Gravity Racing Club Soapbox Challenge; three made.

2004

Type 111 Series 2 Exige; 2,900 made.Federal Elise, Elise 111R: Toyota ZZ 1.8-litre and six-speed gearbox replace K-Series driveline; 8,000 made.

2005

Sport Exige 240R; fifty made.

2006

Tesla Roadster; 2,450 made.Mike Kimberley becomes CEO of Group Lotus, May 2006.Lotus Engineering reconfigured; Paul Newsome becomes MD.

2007

Type 121: Europa S 2.0; 409 made.Europa SE; forty-seven made.Type 111 Elise S; 1,815 made. 111R renamed Elise R.Type 123: Lotus 2-Eleven roadster; 358 made.2-Eleven GT4 Supersport; fourteen made.

2008

Exige 265E and 270E: bioethanol-fuelled models and Eco Elise; three made.Type 111: Elise S, Elise R, Elise SC; 1,402 made.Exige Cup 260; 300 made.Type 122: Evora 2+2; 6,000 made.

2009

Exige S 260; 129 made.Exige Scura.Exige GT3 racer.Mike Kimberley retires, succeeded by Dany Bahar.

2010

Type 124: Evora Cup GT4; thirty made.Type 125: Formula 1-inspired racer; four made.

2011

Elise facelifted, 1600cc Toyota 1ZR-FAE engine introduced; 645 made.Elise Club Racer; 437 made.Evora GTE: LM GTE and GT4 racers.Evora 414E Hybrid.Type 124 Evora GTS and Enduro; six made.Type 124 Evora GTE race car; two made.

2012

Type 111: Exige R-GT; one made.Exige S and S Roadster available; around 1,500 cars made.Dany Bahar quits as CEO.

2013

Exige V6 Cup and Exige V6 Cup R.Elise S Club Racer, Elise S Cup R.Type 122: Evora Sports Racer.

2014

Elise S Cup announced.Jean-Marc Gales becomes CEO.

2015

Exige 360 Cup.Facelifted, supercharged Evora 400.

2016

Elise 250 Special Edition, Elise 3-Eleven and Elise Race 250.Exige 350 Special Edition.Evora GT410 Sport.

2017

Geely acquires controlling stake in Group Lotus. New CEO Feng Qingfeng replaces Gales.Type 111: Elise Sprint, Elise Cup 260.Exige Race 380, Exige Cup 380, Exige Cup 430.Type 122: Evora GT430.

2018

Exige Cup 430 ‘Type 25’, Exige Sport 410, Exige ‘Type 49’ and ‘Type 79’.Phil Popham becomes CEO of Lotus Cars.

2019

Federal Type 122 Evora GT.Type 130: Evija hypercar; 130 cars scheduled.

2020

Type 111: Elise Classic Heritage Editions.Exige Sport 410 20th Anniversary model.

2021

Matt Windle becomes managing director of Group Lotus.Type 131: Emira, replacement for Evora.

Brought together at Classic Team Lotus HQ, the Type 72 Formula 1 car and Evora GT410 Sport exemplify Lotus’ fundamental heritage of building road and race cars.

INTRODUCTION

The history of Lotus is a tale that’s been told a dozen times and more. Indeed, I’ve written in some depth about elements of the Lotus story, from the Types 25 and 33 to the Types 78 and 79 Formula 1 cars, with detailed tomes about the Elise and Exige, as well as driver biographies on erstwhile Lotus Grand Prix stars Ronnie Peterson, Graham Hill and Ayrton Senna – plus the turbulent black-and-gold John Player Special era when I operated the JPS Motorsport press office. So, here is the full Lotus marque history, broken down into five main chapters and sidebars, recounting what cars were made at each factory, how the business fared, and what race successes ensued: a summary of the ups and downs, the highs and lows.

We find that, while most Lotus road cars were developed over the years and evolved with mechanical upgrades and facelifts, Lotus racing cars inevitably had a very much shorter shelf life, very likely replaced year on year, and the unfolding story and successive type numbering reflects that high turnover. And while numbers built of road cars such as the Esprit and Elise run into thousands, the majority of racing cars are in the twos, threes and fours.

The 3.5-litre V8 ‘Final Edition’ version of the Type 82 Esprit, culmination of two decades and sixteen evolutions of the Hethel-made supercar, flashing those characteristic headlamps on a backroad in Hoosier National Forest, Indiana.

A line-up of Lotus Mk 6s in the infield at Classic Le Mans.

Hairpin heaven: on a drive from Barcelona to the Muntanya de Montserrat, negotiating the serpentine backroads of this Spanish national park in the supremely nimble S2 Elise.

The Eleven S2 ‘Custard Climax’ of Neil Twyman and Olly Hancock at Portimao during the 2011 Algarve Classic event.

Lotus has a devoted following of fans for whom the marque is a way of life, and is not by any stretch of the imagination a mass producer, but a niche specialist of truly iconic and exquisite cars, both for road and track. From my first-ever childhood trip to Brands Hatch, I’ve been gripped by its sensory stimulants – aural and olfactory as well as visual – the heady, pungent pong of Castrol-R racing oil, the harsh bellow of unsilenced multi-cylinder racing engines, the burning rubber of screeching tortured tyres, all fundamental elements of Lotus DNA. To balance the inevitable preponderance of race material, I’ve included interviews with key individuals and images from drive trips undertaken in various Lotus road cars.

Lotus’s history has been episodic, an up-and-down saga of triumph and tragedy, of technical and aesthetic masterpieces – and the odd dud. From its first tentative steps as the hobby of an ambitious Colin Chapman in 1948, to the founding of the company in 1953, the marque flourished during the mid-1950s as the producer – on a hand-to-mouth basis – of aerodynamically brilliant sports racing cars, thanks to designer Frank Costin and Chapman’s career in the aero industry. These cars were sought by amateur racers and run at events such as Le Mans by Chapman and his new ‘Team Lotus’. Competition successes attracted more business – though the innovative road-going Elite model served as a shop window for more customers; like Enzo Ferrari, Chapman produced road cars to fund his racing cars. By 1959, the firm had outgrown its Hornsey premises and relocated to new factory buildings at Cheshunt, Hertfordshire.

GRAND PRIX SUCCESS

By 1960, Lotus and Cooper led a revolution in Grand Prix racing, as well as up-and-coming categories – Formula Junior (a substitute for Formula 2 and 3) and sports car racing. Aided by rule changes that called for small-capacity engines, Lotus and Cooper swept the board, joined briefly by Porsche and Lola. While Coopers were regarded as products wrought in a foundry or smithy, Lotuses were finely crafted – fragile, even – built to the minimum weight limits on the premise that if they held together till the finish line was crossed, and then fell apart, that was fair enough. Stirling Moss settled out of court in 1960 for injuries sustained after a wheel fell off his Lotus at that year’s Belgian GP.

An Elan 26R, part of a collection belonging to Roy Walzer, based in Litchfield, Connecticut. Flared bodywork suits the wider, cast magnesium wheels, and there’s a factory-fitted singleskin hard-top.

Colin Chapman’s close rapport with Scottish ace Jim Clark won the Formula 1 world title for drivers and constructors in 1963 driving the radical Type 25, and also came close to winning the Indianapolis 500 with its arcane rules and archaic runners. Clark won the Formula 1 championship again in 1965, still in the Type 25/33, as well as the Indy 500. Meanwhile, on the road, Lotus’s Cheshunt factory was producing the Elan, a fine-handling fibreglass-bodied sports car.

A Type 47 comes into the pits during the Le Mans Classic, referencing the Gold Leaf colours of 1968. Classified in 1968 as a Group 4 sports car rather than a GT, the 47A proved reliable and quick enough to set ten new lap records that season.

The Lotus Elan 26R of Stéphane Gutzwiller and Ivo Salvadori heads a BMW through Brünnchen curve on the Nordschleife in the heat of the 2012 Nürburgring Old Timer meeting.

Another major rule change in 1967 partnered charismatic Graham Hill with Clark in the Type 49 – another inventive construction, though Clark was killed in a Formula 2 race early in 1968. Devastated, Chapman was on the point of giving up, but Hill galvanized the team and went on to win the 1968 World Championship. Significantly for Team Lotus, and motor racing in general, Chapman embraced big-time commercial sponsorship for 1968, welcoming cigarette manufacturer John Player and presenting Lotus racing cars in the livery of the Gold Leaf brand. This opened the doors to major commercial investment in motor sport as a marketing tool.

Meanwhile, Lotus Cars continued to produce the Elan, which was joined by the Europa, a mid-engined Renault-powered car that also served on the track. Lotus Components created the makings of racing cars, mainly Formula Fords, for private customers. Team Lotus’s next star driver was whirlwind Austrian Jochen Rindt, who won the 1970 World Championship for Lotus, albeit posthumously, having been killed at Monza near season’s end: no other driver subsequently gained more points than he had accrued.

Master of the four-wheel drift on full opposite lock, Ronnie Peterson led the 1973 Spanish Grand Prix at Montjuïc Park in the JPS Type 72 until his gearbox gave up under the rigours of shifting on the Barcelona street circuit.

Jump to 1972, and Team Lotus livery switched to the black and gold of JPS John Player Specials, and young Brazilian star Emerson Fittipaldi drove the Type 72 to win the world title for Lotus. For 1973, Emerson was joined by Super Swede Ronnie Peterson, regarded as the fastest man in Formula 1, despite his laconic manner. They won the constructors’ prize in 1973, but split the race wins to their detriment, allowing Jackie Stewart to scoop the driver’s title.

GOING UPMARKET

On the road, the Elan +2 was built alongside the Elan two-seater and the Europa. Lotus had been on a roll, both on track and on the road, and Colin Chapman elected to take the road car range upmarket into the grand touring segment, announcing the front-engined Elite Mk 2, Eclat and mid-engined Esprit – which was a significant declaration of intent.

Team Lotus drivers were allocated their own Lotus road cars, and this is Ronnie Peterson at his Maidenhead home in 1974 with his Elan +2, which he drove flat-out absolutely everywhere. The Granada was Ford’s contribution to his stable.

The turbocharged 2.2-litre Type 82 Esprit S4 came out in 1993, featuring revised bumper panels and sills, with sculpted ducting funnelling air into the engine bay, further ducts covering the scoop behind the rear window, and with the smaller rear wing now attached to the tailgate.

The next march that Chapman stole on the Formula 1 firmament was ‘ground effect’. To generate maximum downforce to gain superior traction and road-holding, he visualized a car configured like an inverted wing. By harnessing airflow under the chassis by means of venturi in the side pods and trapping it underneath by means of side skirts, the whole vehicle was sucked down onto the track. The faster it went the more downforce was generated. Here was something for nothing – the ‘unfair advantage’!

There was inevitably an element of triumph and tragedy about the Lotus saga: there were innumerable race wins, but a lot of drivers were killed in the 1960s, and in 1978 Lotus lost two Swedes – Gunnar Nilsson to cancer and Peterson to a surgeon’s blunder after an accident in the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. Peterson’s team mate Mario Andretti was World Champion in what was, under the circumstances, a pyrrhic victory. It proved to be Team Lotus’s last World Championship win.

Andrew Beaumont channels Ronnie Peterson in his 1978 Type 79, run by Classic Team Lotus, heading out of the paddock for a run up the Goodwood Hill in 2014.

Jubilation on the podium, with Ronnie Peterson, Mario Andretti, Colin Chapman and Clive Chapman celebrating a one-two at Zandvoort, one of four Grands Prix where they finished first and second out of a sixteen-race schedule.

Colin Chapman, ever the innovator and rule bender, proposed a twin-chassis Formula 1 car, the Type 88, for the 1981 season, but was snubbed by the FIA who control the sport, and rival teams. Chapman again contemplated quitting the sport, and was seriously preparing to build microlight aeroplanes and their engines. Chapman and Kimberley started building Lotus’s engineering consultancy business in 1977, starting with the rally-winning Talbot Sunbeam Lotus project. This was followed by Chapman eventually deciding to take on the DeLorean project, which involved turning a GT concept into an engineered and US-certified production specification in just eighteen months. Just before a major DeLorean Motor Company (DMC) accounting fraud was alleged, Chapman suffered a heart attack and died in December 1982, aged just fifty-four.

LIFE AFTER CHAPMAN

At Team Lotus, the reins were picked up by team manager Peter Warr, who ran the Formula 1 racing cars throughout the 1980s and through to 1991, when Peter Wright and Peter Collins took over until it collapsed in 1994. During that period, top drivers were Nigel Mansell and then Brazilian ace Ayrton Senna. Had Team Lotus been able to give Senna sufficiently reliable cars, they would have won the World Championship again. As it was, they couldn’t, and he went off to McLaren and was champion the following year.

The Series 1 Elise in Gold Leaf Team Lotus ‘Type 49’ livery, posed in front of Goodwood House. This was one of the first Heritage Editions, released in 1999, celebrating the marque’s first taste of commercial sponsorship back in the late 1960s.

This 2002 Final Edition Esprit rollercoasters an Indiana backroad on a LOG28 run out of Indianapolis to Nashville in Brown County National Park. Just eighty-two cars were built, all to North American specification.

Group Lotus, meanwhile, was in deep financial trouble, caused by recession, AMEX bank’s withdrawal of its loan and the collapse of the global car market. After Chapman’s death, Mike Kimberley was appointed group managing director, working with Toyota funding support to enable Lotus to survive the next six months, and then ensuring a small recapitalization and stabilization of the company in July 1983. From 1983 to the end of 1985, Lotus Engineering was expanded successfully, though the car company lacked investment for new models, including a joint venture M90 Elan with Toyota.

General Motors acquired Lotus in January 1986, bringing major investment to the car company, and enabling production of the M100 Elan that replaced the lost M90 project. In 1993, GM sold Lotus to Romano Artioli’s Bugatti concern, and though Artioli relinquished control in 1996, with ownership passing to state-owned Malaysian car maker Proton, he instituted the construction and launch of the Elise, a major factor in the perception of Lotus, since it harked back in several ways to the company’s innovative competition roots.

In 2000, the Series 1 Elise made way for the Series 2 model and its principal derivative the Exige, and the concept gradually matured with powertrain revisions, styling facelifts and chassis modifications through the next twenty years. The long-running Esprit finally went out of production in 2002, though a replacement was envisaged. The Series 2 Federal version of the Elise came out in 2004, along with the S2 Exige. The Toyota ZZ 1.8-litre twin-cam engine and six-speed gearbox were adopted at the same time, replacing the K-Series driveline.

The Type 121 Europa was released in 2007, with the enhanced SE arriving the following year. I drove one from Stuttgart to Marrakech, and found the 2.0-litre turbo GM engine made the Europa SE nearly as quick as the Elise SC.

Mike Kimberley joined the holding board in 2005, and was appointed Group Lotus CEO in 2006, but was forced to retire early in 2009 when he seriously injured his back in a fall in an icy car park. In the interim, he’d conceived and initiated the launch of the Toyota V6-powered Evora, rebuilt Lotus Engineering, and returned the company to operating profit in 2008 and 2009.

It had been going very well up to that point. Then, in 2009, Proton appointed as Kimberley’s successor former Ferrari ‘commercial and brand’ vice president Dany Bahar to take Lotus into what proved an overly ambitious expansion programme, aimed at rivalling Italian supercar makers such as Ferrari and Lamborghini. There was, briefly, a ruthless drive to go upmarket, with six projected new models announced at the 2010 Paris Show, and ‘lifestyle’ the all-embracing mindset. When that didn’t work out, the Malaysian government shifted control from Proton to DRB-HICOM, the state-owned car distribution conglomerate, changing top management at Lotus in the process. Key Lotus engineering and executive staff resigned or were dismissed.

The press office lent me a range-topping 2020 Evora GT410 Sport for a few days, in the course of which its responsiveness was abundantly apparent.

The Evora GT410 shelters beneath a yew tree at Salle, Norfolk. It’s quite apt, as Évora is the capital of Portugal’s Alentejo department, and means ‘yew tree’.

The new contingent of Malaysian owners did not fully comprehend nor appreciate what an iconic entity they had at Hethel, and no major investment was made in creating new product, or doing more than evolving the existing product ranges. In fairness, this is because they caught a cold over the Bahar programme. Due diligence, it was called. Nevertheless, Lotus had stagnated.

Then, in 2017, salvation arrived in the shape of the Chinese global automotive company Geely. This bullish conglomerate, which also bought a 49 per cent share of Proton, had already taken over Volvo in 2010 and made beneficial changes there, and similar promises were made for Lotus. In 2020, The Economist magazine declared that Geely ‘might well succeed where others had failed’.

CHAPTER ONE

THE HORNSEY YEARS, 1952–60

Company founder Colin Chapman enrolled at University College, London, in 1945, to read structural engineering. While there, Chapman and his friend Colin Dare traded second-hand cars, helped by the fact that the Warren Street dealers’ mecca was very close by; but when the basic petrol ration was suddenly withdrawn in October 1947 – and fuel rationing continued until 1954 – Chapman was left with a stock of cars that he had to sell off at a loss. The last one was a fabric-bodied Austin 7, and he dismantled it and clad the chassis in alloy-bonded plywood for greater rigidity. Chapman was a member of the university air squadron and to a degree it followed the principles of aircraft construction.

A decade later, Lotus took a stand at the Do-It-Yourself Exhibition, demonstrating just how long the make-do ethos held sway. Those were the days of new artificial materials like Formica and Fablon, of plywood and chipboard, and it was respectable enough for up-and-coming celebrities, including Graham Hill, to visit the Lotus stand. Chapman’s first effort at a trials car in 1948, retrospectively named the Lotus Mk 1, was essentially an Austin 7.

Ron Gammons in his Eleven Le Mans during the Masters Historic Sports Cars round at Portimao, part of the Algarve Classic Festival.

THE FIRST LOTUSES

Chapman spent time mulling over technical treatises at the Institute of Mechanical Engineers’ library to discover what stresses cars were subjected to, and what had to be done to counteract them, and his early cars began to embody some of the principles he absorbed. Not many car designers took these things as seriously as Chapman, and the spaceframe chassis and aerodynamic bodied models of the 1950s should be viewed in this light. He extended the rear of the Mk 1 body to accommodate passengers – or trialling ballast. The Austin 7 special was assembled in a lock-up garage behind his girlfriend Hazel Williams’ parents’ home in Alexandra Park Road, north London. She supported Colin in his obsession with cars and speed, providing him with the wherewithal and premises for tinkering with engines.

Inspired by ‘mud-plugging’ trials competition, Colin Chapman created his own contender from a twentyyear old Austin Seven in 1948, replacing the fabric panels with aluminium to produce the Mk 1 Lotus.

Colin Chapman, right, and a bunch of girlfriends cluster round the Mk 1 at a trials event in 1948.

The car was registered OX 9292 as a Lotus Mk 1, early in 1948, and Chapman, partnered by Hazel, campaigned it successfully in the mud and ruts of trials competitions as far afield as Cheshire from 1948. Perhaps Chapman’s most notable discovery was that inverting the rear leaf springs cured the Austin 7’s propensity to oversteer. He also created an independent front end by splitting the front axle beam and pivoting it in the centre, thus ensuring the wheels were vertical during cornering.