Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

The first water-cooled Porsche Turbos were launched in 1979, evolving through Turbo variants of the front-engined 924, 944 and 968. With the new Millennium came the first of the water-cooled rear-engined 922 Turbos, and from 2017 turbos have been applied to the mid engined Boxster and Cayman models. Johnny Tipler describes the progression of these popular cars from their introduction to the present day. Included are interviews with Derek Bell, Jacky Ickx, Walter Rohrl, Allan McNish, Jorg Bergmeister and Hans-Joachim Stuck. Full development and design history for all seven models is given along with specification tables and detailed motorsport achievements.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 540

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PORSCHE

WATER-COOLED TURBOS

1979–2019

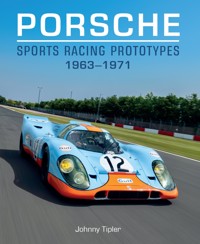

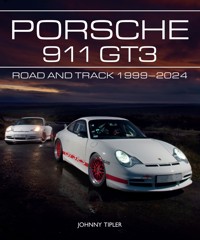

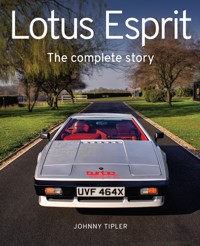

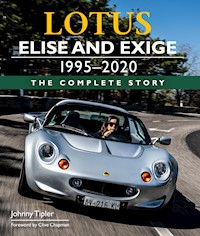

TITLES IN THE CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS SERIES

Alfa Romeo 2000 and 2600

Alfa Romeo 105 Series Spider

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV and Spider

Alfa Romeo Spider

Aston Martin DB4, DB5 & DB6

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin V8

Audi quattro

Austin Healey 100 & 3000 Series

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Classic Coupés 1965–1989

BMW Z3 and Z4

Citroen DS Series

Classic Jaguar XK: The 6-Cylinder Cars 1948–1970

Classic Mini Specials and Moke

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Ford Consul, Zephyr and Zodiac

Ford Transit: Fifty Years

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta Road and Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 and 2, S-Type and 420

Jaguar XJ-S

Jaguar XK8

Jensen V8

Land Rover Defender

Land Rover Discovery: 25 Years of the Family 4×4

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

MG T-Series

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz ‘Fintail’ Models

Mercedes-Benz S-Class

Mercedes-Benz W113

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes SL & SLC 107 Series 1971–2013

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

Peugeot 205

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Air-Cooled Turbos

Porsche Boxster and Cayman

Porsche Carrera: The Air-Cooled Era

Porsche Carrera: The Water-Cooled Era

Range Rover Sport

Range Rover: The First Generation

Range Rover: The Second Generation

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley: The Legendary RMs

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover 800

Rover P4

Rover P5 & P5B

Rover SD1

Saab 99 & 900

Shelby and AC Cobra

Subaru Impreza WRX and WRX STI

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire & GT6

Triumph TR6

Triumph TR7

VW Karmann Ghias and Cabriolets

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

PORSCHE

WATER-COOLED TURBOS

1979–2019

Johnny Tipler

Foreword by Alois RufWith photos by Antony Fraser

First published in 2020 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2020

© Johnny Tipler 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British library Cataloguing-in-Publication dataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 694 4

An original artwork of a Porsche 991 GT2 RS, painted by Caroline Llong, a Parisian artist based in Marseilles who specializes in depicting cars, and Porsche and Ferrari in particular. As she says, ‘All my paintings are resolutely modern, and characterized by brilliance of colour, depth of light, dazzling reflections and an amazing energy.’ (www.e-motion-art.fr). CAROLINE LLONG

Artwork of a Porsche 997 Turbo created specially for the book by French watercolourist Laurence B. Henry ([email protected]). LAURENCE B. HENRY

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is my fifth book about Porsches, all written for Crowood, and like its predecessors, Porsche Water-Cooled Turbos 1979– 2019 is prolifically illustrated with photographs by Antony Fraser, my regular work colleague, so I’m indebted to him for providing shots taken on our forays into the countryside when we visit specialists in Britain and Europe, travelling in press cars provided by Porsche GB as well as our own vehicles.

I’ve received support from Porsche GB press office in respect of access to state-of-the-art 911 Turbos, while at the Porsche Museum in Zuffenhausen, Jessica Fritzsch ensured photoshoots happened; other helpful folk at the factory included Katja Leinweber, Tobias Hütter, Tony Hatter and Dieter Landenberger, as well as former design head Harm Lagaaij. I’ve also much appreciated assistance from Porsche photographic archivists Jens Torner, Tobias Mauler and Amel Ghernati, who have unstintingly presented legions of pictures from their library over the years, and I’ve tried to use photos that have never been seen before, at least by me. Other photographers who have supplied images include Peter Meißner of Moment-fotodesign, Sarah Hall, Alex Denham, Kostas Sidiras, Carlie Thelwell, Christopher Ould and Peter Robain.

Comrades in arms (or at least in cups): photographer Antony Fraser and author Johnny Tipler with 997 Turbo Cabriolet brave the snow beside the Falkirk wheel.ANTONY FRASER

It’s a real treat to feature paintings of Porsche by some terrific artists – Laurence B. Henry, Caroline Llong, Tanja Stadnic, Alina Knott, Anna-Louise Felstead and Sonja Verducci – who have all supplied images of their work, in some cases executed specially for the book.

In the course of my job as a freelance journalist I call on a lot of Porsche specialists in Britain and Europe, as well as interviewing racing drivers and personalities associated with the marque. I visit establishments such as the Porsche Museum at Zuffenhausen, and attend race meetings and historic rallies where there tend to be a preponderance of Porsches. In this context I’m particularly fond of the Nürburgring 24-Hours, Spa Six-Hours and Monte Carlo Rallye Historique. The point is, I meet a great many Porsche enthusiasts who’ve become friends and have been helpful one way or another in the compilation of this book. So, here they are, in no particular order: Johan Dirickx, Mike Van Dingenen, Hans Dekkers and Joe Pinter at 911Motorsport; John and Tanya Hawkins at Specialist Cars of Malton; Ian Heward at Porscheshop; Paul and Rebecca Stephens; Adrian Crawford, Richard Williams and Louise Tope at Williams Crawford; Steve Bennett, editor of 911 & Porsche World magazine, from whom I get many of my commissions; Andy Moss and Stuart Manvell at SCS Porsche; Andrew Mearns at Gmund Cars; Ollie Preston at RPM Technic; Simon Cockram at Cameron Cars; Mark Sumpter at Paragon Porsche; Martin Pearse at MCP Motorsport; Jonny Royle and Jonathan Sturgess at Autostore; Joff Ward at Finlay Gorham; Phil Hindley at Tech9 Motorsport; Russ Rosenthal at JZM; Josh Sadler, Steve Woods and Mikey Wastie at Autofarm; Colin Belton at Ninemeister; Karl Chopra at Design911; Mike at Ashgood Porsche; James Turner of Sports Purpose; and not forgetting the guys at Kingsway Tyres Norwich who diligently swap tyres and balance wheels for me.

Then I must mention my continental friends, beginning with tuner and builder extraordinaire Alois Ruf and his team, including Estonia (Mrs Ruf ), Claudia Müller, Marcel Groos, Marc Pfeiffer, Michaela Stapfer, Anja Bäurle and Anja Schropp, who have always made our trips to Bavaria a real pleasure. And, of course, a huge thank you to Alois for writing the Foreword. Next up, the genial Willy Brombacher and his FVD operation, including his son and daughter, Max and Franziska; Ron Simons, proprietor of RSR Nürburg and RSR Spa, who has provided cars and instructors (Freddy Mayeur!) for laps of these great circuits, and an unforgettable Mosel wine road trip with Kostas Sidiras as attendant snapper. Then, Thomas Schnarr at Cargraphic, whose silencer adorns my Boxster. My colleague and I have also been entertained by Ande Votteler, Manon Borrius Broek, Tobias Sokoll and Marc Herdtle at TechArt, Björn Striening at speedART, Oliver Eigner at Gemballa, Thomas Schmitz at TJS German Sportscars, Michael Roock at Roock Racing, Jan Fatthauer at 9ff, Dirk Sadlowski at PS Automobile, Eberhard Baunach at Kremer Racing, Dmitry Ryzhak and Oleg Kucharov at Atomic Performance Parts and Motorsport Equipment, and Manfred Hering at Early911S. Thanks also to another old friend, Kobus Cantraine, for providing Porsches to have fun in. Likewise, Mark Wegh at Porsche Center Gelderland.

Constructive observations and encouragement from my PA, Emma Stuart, are much appreciated, and I want to mention a swathe of aficionados, colleagues and commissionaires with whom I spoke or drove, including Rachel Parkin, Verena Proebst, Claudio Roddaro, André Bezuidenhout, Brent Jones, Mauritz Lange, Peter Bergqvist, Jürgen Barth, Hans-Joachim Stuck, Jacky Ickx, Vic Elford, Mike Wilds, Mario Andretti, Jörg Bergmeister, Dirk Werner, Klaus Bachler, Mark Mullen, Lee Maxted-Page, James Lipman, Patrick O’Brien, Simon Jackson (editor of GT Porsche magazine), Alastair Iles, Mike Roberts, Lee Sibley (editor of Total 911), Timo Bernhard, Peter Dumbreck, Wolf Henzler, Olaf Manthey, Brendon Hartley, Angelica Grey, Walter Röhrl, Andrea Kerr, Steve Hall, Tim Havermans, Wayne Collins, Peter Offord, Carlie Thelwell, Fran Newman, Joachim von Beust, Kenny Schachter, Ash Soan, Nick Bailey and Els van der Meer at Elan PR, Angie Voluti at AV PR, Sarah Bennett-Baggs, Mike Lane, Angelica Fuentes and Keith Mainland, Keith Seume (editor of Classic Porsche magazine), Andy Prill and Bert Vanderbruggen – to name but a few.

Other benefactors who in no small way enabled the composition of the book include Chris Jones at Brittany Ferries, Frances Amissah at Stena Line, Michelle Ulyatt at DFDS Ferries, Natalie Benville at Eurotunnel, Charlotte Wright at Rooster PR, Natalie Hall at P&O Ferries, Simon and Jon Young at Phoenix Exhausts, Angie Voluti at Vredestein Tyres, Stefanie Olbertz and Kerstin Schneider at Falken Tyres, and Samara Amos at Continental Tyres. Many thanks to all concerned, and hopefully I haven’t left too many people out.

FOREWORD

ALOIS RUF

CEO and owner of Ruf Automobile GmbH, Porsche concessionaire and doyen of turbocharging methodology

We began our first experiments with turbocharging at Ruf Automobile in 1974, fitting a turbo to a 2.7-litre 911 engine, and in 1977 we presented our first Ruf Turbo, developing 303bhp. The first car to bear a Ruf chassis number was the BTR of 1983, running a 3.4-litre Ruf turbo engine producing 374bhp, and our ‘Yellowbird’ CTR achieved international acclaim when it beat the world’s fastest supercars in a media shoot-out at Ehra-Lessien test track in 1987, going at 340km/h (211mph).

The fact that you can utilize the velocity of the exhaust flow to drive a turbo compressor to pre-charge the intake air is fascinating, conceptually as well as in a practical sense, because it is free power that would otherwise go to waste.

The traditional ways of increasing the performance of an engine are by enlarging the displacement of the engine, raising the rpm, and raising the combustion pressure.

The last method works with turbocharging as the most efficient and elegant solution. When the boost ‘sneaks up’ on you, I call it the ‘quiet storm’ – like a ghost that suddenly pops up behind you. You check your speedometer, and the needle shows 50km/h (30mph) more than you expected – achieved in a split second. Instead of squeezing out the horsepower from a naturally aspirated engine, the turbocharger effortlessly elicits the power from a turbo engine, giving it a light-footed feel. All the years spent developing turbocharged engines bore fruit, and the infamous turbo flat spot was banished by balancing the plumbing of the intake and the exhaust side, as well as identifying the ideal initial compression ratio for the engine.

We had proved conclusively that turbocharging worked perfectly harmoniously with air-cooled engines, and so, following on from our experiences with turbocharged engines in the 1970s and 1980s, we were watching carefully to monitor how the transition went from air-cooled to water-cooled engines in the Porsche flat-six racing cars. Le Mans has always been the yardstick for being the hardest endurance race in the world, challenging the race car builders. First, the 956 with water-cooled cylinder heads and 4-valve technology showed it was possible not only to go the distance, but to take the victory as well. Soon afterwards, the 962 followed on with all water-cooled engines. It was clear that future success for this high-performance flat-six engine, which was on its way to delivering 250bhp per litre, could only be achieved with water-cooling. That’s because the cooling media can be brought to the hard-to-reach corners within the cylinder head water-jackets in order to avoid heatnests or hot spots. Soon enough, digital engine management perfected everything, protecting the engine and enabling economical fuel consumption.

Alois Ruf explains some of the CTR-4 Yellowbird’s finer points to the author during a visit to the company’s Pfaffenhausen headquarters.ANTONY FRASER

A couple of Ruf Yellowbirds, separated in time by three decades: the latest CTR-4 (left) and original CTR-1.ANTONY FRASER

Here, at Ruf Automobile, we celebrate eighty years in business in 2019, more than half of which have been, for us, ‘turbo years’. So, we can say with some confidence that turbo is the future for your combustion engines. As a measure of how we have progressed in the last thirty years, you can read all about our latest CTR Yellowbird and its radically different chassis construction in Chapter 4 of this book.

I hope that all car connoisseurs and petrolheads thoroughly enjoy reading Johnny Tipler’s book on water-cooled Porsche and Ruf Turbos.

TIMELINE

1979 The 924 Turbo is introduced.

1980 The 924 Carrera GT is launched.

1981 The 924 Carrera GTS and GTR are in action.

1985 The 944 Turbo goes on sale; it delivers 217bhp from the 2.5-litre straight-four engine.

1986 The 944 Turbo Cup race series heralds the Porsche Carrera Cup.

1988 The 944 Turbo S is introduced, which develops 250bhp.

1991 The 944 Turbo Cabriolet is unveiled.

1992 The 968 Turbo S is a limited edition model with racing intent.

1999 The 996 Turbo debuts at the Frankfurt Show.

2000 The 3.6-litre, twin-turbo, all-wheel-drive 996 Turbo goes on sale.

2002 The X50 tuning package becomes available, raising power from 415bhp to 444bhp.

2003 The 996 Turbo Cabriolet is launched.

2005 The 997 Turbo is unveiled at Geneva Salon, with 473bhp.

2007 The 997 Cabriolet is released.

2007 The 997 GT2 becomes available, featuring rear-wheel drive and capable of 523bhp.

2010 The 997 Turbo S is introduced, with a 3.8-litre engine, 523bhp and seven-speed PDK transmission. The 997 GT2 RS is launched, with 3.6 litres delivering 612bhp.

2013 The 991 Turbo and Turbo S released; the former develops 513bhp from a 3.8-litre flat-six, the latter 552bhp.

2013 The 991 Turbo and Turbo S Cabriolet versions become available.

2015 Facelifted 991 Turbo and Turbo S models go on sale.

2016 All 991 models except the Turbo and Turbo S are powered by new 3.0-litre turbocharged flat-six engines.

2016 The 718 series Boxster and Cayman models powered by 2.0- and 2.5-litre turbocharged flat-four engines appear.

2017 The 718 Boxster GTS and Cayman GTS 2.5-litre flat-four engines develop 361bhp. The 991 Turbo S Exclusive series is launched, comprising just 500 units with a power kit.

2018 The 991 GT2 RS released, developing 690bhp from a twin-turbo 3.8-litre flat-six.

2019 The 935 is launched, a pastiche of a slant-nose racing car from the late 1970s.

2020 The 992 Turbo is unveiled.

INTRODUCTION

From 1973, when Porsche first applied forced induction to its 917 Spyders for use in the North American Can-Am series and the European Interserie championships, it was inevitable that the technology would transfer onto the 911 street car, and the earliest 911 Turbo was shown at the Paris Salon in 1973. The first racing 911s to receive turbochargers were the factory’s Carrera RSR Turbo race cars, one of which finished second at Le Mans in 1974, driven by Gijs van Lennep and Herbert Müller. Porsche’s racing 911s evolved into the 934, hugely successful as a Group 4 car in the GT category of the World Sportscar Championship (Le Mans etc) and US-based IMSA (International Motor Sports Association) series. By 1976, the turbocharged Porsche of choice for international GT racing was the more extreme Group 5 935, which was good enough to win Le Mans outright in 1979. Both the 934 and 935 could have twin turbos rather than single units, depending on in which category or race series they participated.

Porsche’s first road-going application, the 930, or 911 Turbo as it was originally known, appeared in 1974, and remained in production until 1989, to be superseded in 1991 by the 964 Turbo. The high-tech twin-turbo 959 featured as a Group B Paris–Dakar Rally weapon and road-going supercar, produced in very limited numbers between 1983 and 1993. The final incarnation of the air-cooled 911 Turbo was the 993 Turbo, built between 1995 and 1998. Anyone interested in these models might like to look out for my book Porsche Air-Cooled Turbos (1973–1998), also published by The Crowood Press.

Meanwhile, a model line of turbocharged, water-cooled, front-engined Porsches evolved, which I’ve covered in this book, as they are, well, turbos obviously, and they are sports cars bearing the Porsche badge. I wondered whether they commanded a separate book all to themselves, but on balance I elected to bring the total water-cooled oeuvre together here. The front-engined cars were manufactured in parallel with the air-cooled 911s, starting with the 924 Turbo, which was in production between 1979 and 1982. This model spawned the 924 Carrera GT, followed chronologically by the 944 Turbo (1985–91), Turbo S and Turbo Cup derivative. The final example of the front-engined Turbos was the 968 Turbo (1992–3) and its Turbo S and RS offshoots. Then, with the dawning of the new millennium, came the first of the water-cooled 911 Turbos, the 996 Turbo, followed in 2005 by the 997 Turbo and in 2013 by the 991 Turbo. These mainstream models begat ‘S’ versions as well as GT2 and GT2 RS derivatives, the main difference being that the mainstream cars were four-wheel drive and the competition-oriented GT2s were rear-drive only. Minor facelifts were introduced in 2017, and the 992 will inevitably usher in a Turbo version in late 2019 or 2020. Meanwhile, advances in environmental legislation and turbocharging efficiency meant that, from 2016, all petrol-engined Porsche cars, bar the GT3, were turbocharged, not just the Turbos, allowing us to consider the forced-induction 991 GTS and 718 Boxster and Cayman models in the book’s last two chapters.

Turbo trio: a striking line-up of 911 turbos composed specially for the book by Jonathan Sturgess at Cambridgeshire-based Autostore (www.autostore.co.uk), comprising a 996 Turbo, 997 Turbo and 991 Turbo Cabriolet.CHRISTOPHER OULD

The 924 Carrera GTS was a derivative of the 924 Carrera GT, introduced in 1981, created predominantly for rallying and similar competition purposes.ANTONY FRASER

Another rare car developed at Weissach by Jürgen Barth, the 968 RS Turbo Club Sport is one of four RS-Ts, campaigned in South Africa in 1993 before being imported into Great Britain.ANTONY FRASER

Finished in Velvet Red Metallic, this 944 Turbo is a rare Club Sport version, originally delivered in Finland in 1988 and now resident in Belgium.ANTONY FRASER

First of the water-cooled turbocharged 911s, the 996 Turbo was introduced in 2000. The intakes in the front panel feed cooling air to brakes and radiators, while ducts in the rear three-quarter panels ahead of the wheel arches serve the intercoolers.JOHNNY TIPLER

As the water-cooled 911 Turbo morphed into its third generation, the 991 version released in 2013 took the design a stage further, with more restructuring of ducting and aero, and the coupé shape bulked up with each evolution.JOHNNY TIPLER

Launched in 2005, the 911 Turbo’s shape was rationalized with the 997 model, with air intakes and light housings better co-ordinated than on its predecessor.JOHNNY TIPLER

The 991 GTS is a great result of Porsche’s move to turbocharge the majority of their petrol-engined models. This is FVD Brombacher’s interpretation, parked at holzschläger Matten-Kurve on the schauinslandstrasse near Freiburg.JOHNNY TIPLER

TURBOCHARGING

Open up the engine lid on modern Porsches and you’re mainly confronted by plastic covers concealing the mechanicals that lie beneath. Up on a ramp it’s easier to see what goes on, and it’s while looking upwards from down below that you perceive the turbochargers and their integral positioning within the exhaust system. We’ve come to take them for granted because they have become an almost standard piece of equipment – certainly there have been turbocharged models consistently in the Porsche range since 1974.

While most readers will know what a turbo does, this is a book about cars that specifically use them and are designated as such, so it would be remiss not to start with a basic overview of how a turbocharger functions. The turbo is basically an air pump that takes air at ambient atmospheric pressure and compresses it to a higher pressure, feeding the compressed air into the engine’s cylinders via the inlet valves. Engines are dependent on air and fuel, and an increase in either will increase power output. So, to augment airflow, compressed air is blown into the engine, mixing with the injected fuel and enabling the fuel to burn more efficiently, thereby increasing power output.

The turbocharger harnesses the engine’s exhaust gases to drive a turbine wheel that’s connected by a shaft to a compressor wheel. Instead of discharging down the exhaust pipe, hot gases produced during combustion flow to the turbocharger. The exhaust gases spin the turbine blades up to a mind-boggling 150,000rpm. The compressor sucks air in through the air filters and passes it into the engine. As the exhaust gases are expelled from the engine via the exhaust valves, they are passed to the turbine fan within the turbo, and so the cycle continues. The additional oxygen consumed enables a turbocharged engine to generate around 30 per cent more power than a non-turbo unit of the same cubic capacity.

The turbocharged engine ideally needs an intercooler to moderate the temperature of the incoming air. That’s because, in passing through the turbo blades and being thus boosted, it gets exceedingly hot, and this is not good news for the engine. Most turbocharged engines, certainly in a competition context, employ an intercooler. This is basically an air-to-air radiator, usually mounted prominently in the car’s airstream – for example, at the front of the engine bay in the case of the 924 Carrera GT and in the rear wing of the 930. Hot air from the turbo goes in at one end and is cooled as it passes through the intercooler, just like a water-cooled car’s radiator, before entering the engine at a much lower temperature and thus denser.

The alternative means of applying forced induction is supercharging, which was more widely used to boost engine performance in the 1930s. The difference between the two units, supercharger and turbocharger, is that the supercharger derives its power from the crankshaft, whence it’s driven by a belt (in the same way as the water pump and alternator), whereas the turbo draws power from the engine’s exhaust gases. Superchargers spin at up to 50,000rpm while the turbocharger can spin much faster. Emissions wise, the supercharger doesn’t have a wastegate, whereas turbos have catalytic converters to lower carbon emissions. Turbochargers run extremely hot and need to be well insulated. Superchargers deliver boost at lower revs than a turbocharger whereas the turbo works best at high engine speeds. In practical terms, the supercharger is easier to install, though it takes a small portion of the engine’s power in its operation. Turbochargers are quieter in operation, and fuel economy is affected less adversely with a turbo’d engine, while superchargers are more reliable and easier to maintain than the more complex turbocharger. The turbo mutes the exhaust note, so if, like me, you derive a certain ecstasy from the raw rasp of a Porsche flat-six, air- or water-cooled, you’ll know that the gruff boom emitted by a turbocharged car is slightly anticlimactic by comparison. There are fairly clear advantages and disadvantages to both forms of forced induction, but since turbos work better with high-performance applications and, at the same time, are more efficient in dealing with emissions, Porsche took the turbo option.

From 2017, all Porsche 911s – bar the GT3 – were turbocharged, though not identified as such. This is the 991 GTS, revealing twin turbos installed within the exhaust systems on either side of the engine.ANTONY FRASER

The 924 Carrera GTS’s 1984cc slant-four engine achieved a maximum 1.0 bar turbo boost to produce 245bhp via its 40 per cent limited-slip differential, enabling a 0–100km/h time of 6.2sec and a top speed of 249km/h (155mph).ANTONY FRASER

Cutaway of a KKK turbocharger, conveniently left in my hotel room at Breidscheid beside the Nordschleife, revealing the component’s internals, which basically consist of the compressor casing at top left and compressor wheel that’s connected by a shaft to the turbine wheel, which is accommodated in the turbine casing. For a full description of forced induction, i recommend getting hold of a copy of Alan Allard’s Turbocharging and Supercharging.JOHNNY TIPLER

CHAPTER ONE

THE FRONT-ENGINED TURBOS: 924, 944 AND 968

THE 924 TURBO

Four decades ago, the 924 was the entry-level Porsche. In 1979, the model took a major leap up market in the shape of the 924 Turbo. The 924 Turbo went out of production in 1982, and was superseded in the forced-induction stakes by the 944 Turbo and subsequent 968 Turbo. In recent years I’ve been lent a few by Andrew Mearns of Gmund Cars, Knaresborough, and driven them over the Yorkshire Dales, where their competent handling provided compelling evidence that their time has come again. Andrew has a soft spot for the 924 Turbo himself:

It’s a nice car to drive. People are looking at them again, thinking, ‘Hang on a minute, a 924 Turbo for £18 grand,’ and this is entry-level money for any decent classic car. In that context, I think the 924 Turbo is still slightly undervalued, and in practical terms, as a sports car it’s very well put together, though it is quite quirky because the turbocharging is old school, with a certain amount of lag as it’s a relatively big turbo.

Social media is a fair barometer for what’s vexing and sexing people – from the hysterical to the merely eye-popping – but I was surprised that there were over twice as many ‘likes’ for the pic I posted of a 924 compared with a hunky 911 backdate. The comments on the 924 revealed much greater fondness, whimsy even, for the front-engined cars. They’re not exactly comfortable bed-fellows with the 911 Turbos that constitute the greater part of this tome, but they are nevertheless bona fide Porsche sports cars and thus they have a chapter dedicated to them. So, my task is to take a run out onto the bleak, sheep-frequented moorland byways of the Yorkshire Dales National Park and see how the 924 Turbo has stood the test of time.

Cheddar gorgeous: the 924 Turbo was available in quite sophisticated livery combinations including two-tone and pinstriping in the early 1980s.ANTONY FRASER

As the cut-off eligibility year marches into the 1980s, more 924 Turbos are entered in the Monte Carlo Rallye Historique. Here, the French car of Glasgow-starters the Grangeons rounds a hairpin descending the Col de Perty in the Rhône-Alpes in 2018. Snapper Alex Denham is the figure at first right.JOHNNY TIPLER

Encapsulating Porsche’s expertise with turbocharging, the 924 Turbo bridged the performance gap between regular 924 with 125bhp and the 204bhp 911 SC. Launched for the 1979 model year with 170bhp, power rose in 1981 to 177bhp. The 924 Turbo was also designated the 931/932, and production totalled 11,616 units. The 924 Turbo shown here was recently acquired by Richard Kirk, who is Andrew’s right-hand man and has a long history with the model. It’s a second-generation car and has the large lift-out sunroof panel too. The 2.0-litre straight-four was modified to better handle the extra turbo boost, including lowering the standard 924 compression ratio and fitting a new cylinder head with better flow characteristics, plus an oil cooler.

The Turbo has a five-speed transaxle gearbox, with dog-leg first, and I find the slots are much closer than in the four-speed. The steering feel and feedback is also different, and it’s weighted subtly differently. Among the noteworthy details are the NACA cooling duct in the bonnet and the slatted bonnet front and the slotted valance, which provide airflow to the oil cooler. The Turbo’s multi-spoke forged alloy wheels reference contemporary BBS lattice centres and have five bolts, as opposed to the standard 924’s four studs, and are shod with Falcon Azenis 195/35 × 16 tyres all round. The Turbo has a flap over the fuel cap – advocating 98 octane on the label – superseding the regular 924’s lockable finger-grip cap.

The colour of this one is called Mocha Black, a deep brown hue that’s become quite fashionable recently. The sticker in the back window is that of the supplying dealer, Dingle Garages, Colwyn Bay, and quite avant-garde for 1981. Richard explains:

There’s a few things that aren’t practical in modern use, like the radio, which is quite crackly, but it is the original radio so I wouldn’t want to change it. In the service history there’s a handbook for a CB radio so I assume that’s what the antenna mount is for on the rear three-quarter panel. It’s all the little clues like this that tell you the history of the car.

Mileage is quite low at 72,000km (45,000 miles), and though the speedo shows just 24,000km (15,000 miles), that’s because the speedo was replaced at circa 48,000km (30,000 miles), attested by the stamps in the service book. Apart from the Turbo graphic on the sill there’s nothing that shouts turbo, not even a boost gauge. The upholstery is Berber check, a nice combination of two-tone brown and beige, which looks like a luxury option compared with the pinstripe in the standard 924. Richard’s Turbo history goes back more than three decades.

If you had a child seat fitted in your car, once the child outgrew it they would give you your money back when you returned it. It was a safety incentive, so I took my Turbo along and said, ‘Right, put a child seat in the back,’ and they mounted it on top of the transmission tunnel between the rear seats. My daughter remembers those days fondly, and she’s in her thirties now! And, yes, I did get my money back.

In the Yorkshire Dales, a 924 Turbo and its standard 924 stablemate both provided entertaining drives over the moorland byways.ANTONY FRASER

The 924 Turbo’s slant-four was based on the Audi 100 block with single overhead camshaft head and 7.5:1 compression ratio (later 8.5:1), to improve low-speed throttle response and better handle the extra turbo boost. Power output was 180bhp at 5,500rpm.ANTONY FRASER

Cabin interior of the 924 Turbo, showing fabric-upholstered seats, handbrake to the right of the driver, and generic 1980s Porsche four-spoke steering wheel.ANTONY FRASER

Driving the 924 Turbo on the Yorkshire Dales hill roads, the driver has to get acclimatized to its dog-leg first gear and pedal position, but finds it a willing and compliant car on the undulating terrain.ANTONY FRASER

The 924 Turbo on a run out on the moorland byways of Nidderdale in the Yorkshire Dales National Park.ANTONY FRASER

This 924 Turbo, driven by Swedish superstar Åke Andersson and navigated by talented co-driver Anna Sylvan, negotiates a hairpin heading from Sisteron towards the Route Napoleon during the 2013 Rallye Monte Carlo Historique.JOHNNY TIPLER

We motor out onto the upland wilderness of Nidderdale fells. The first thing to get acclimatized to is the seating position, which, although the seat is low-slung in the cab, means I am sitting quite close to the top of the windscreen so that my hat is bumping on the sun visor. Personally, I would welcome more seat adjustment and to be sitting slightly lower in the driving position. The pedal position also takes some getting used to, being oriented slightly differently in the pedal box from what I’m used to (which is currently a 986 Boxster S).

The 924 Turbo is an eager car; there are one or two controls to get used to, such as the dog-leg first gear and the handbrake being to the right of the (RHD) driver’s seat. The view ahead is interrupted by the pop-up headlights that seem somewhat comical today, though you might recall that the much-vaunted Ferrari Daytona and various Lotuses also had a similar lighting arrangement, and we also have to remind ourselves that when stylist Harm Lagaaij drew the 924 in 1973, the Daytona was very much the car of the moment.

Performance wise, there’s no comparison, of course. The 924 Turbo’s acceleration is reasonably swift, though not spectacularly rapid. There’s plenty of torque, pulling from quite low down in third gear, and once it’s warmed up there’s a nice burr… from the exhaust. It’s fluent enough through the bends, and I drop from fourth to third to get around quicker corners. The brakes are a bit spongy and not so convincing, though again I tell myself it’s a forty-year old car. It’s swishing and swaying along quite nicely, and through the twistier sections turn-in is easy-over progressive, the steering is accurate and the handling neutral, and there’s no inclination towards oversteer or understeer. It’s a decent ride, if a bit on the bouncy side. Winding through undulating hill country I’m using third for the most part, and for the corners I’m mostly leaving it in third as well, as it’s torquey enough for that to work for most bends, with some sharper turns and steep hills above the cattle grid zones requiring second. The car is also stable in a straight line, and I’ve wound it up to 115km/h (70mph) on a B-road – and, as luck would have it, I’m blocked by a horsebox at the very point where we pass a speed camera van: here, in the middle of nowhere, in God’s own country. My colleague is less fortunate, however, having already passed the horsebox.

The 924 Turbo is a sprightly performer, edging the standard 924 in that regard, with firm ride and nice turn-in to corners, where I can balance it neatly on the throttle. The steering is a bit of a battle when turning around in a tight spot, as I do for the moorland photoshoot, but easy enough when in motion, and there’s a pleasing delicacy about the gearshift on the move as well. There is a little bit of lag but, really, it’s just a question of being in the right gear at the right time and looking for the turbo spooling up, and then you get the power surge. Does it feel much faster than the standard 924? It’s meant to be 2.5sec quicker to 60mph, but I’m not sure there’s that much in it in practice.

It’s evaluation time. I’m burning up the back road from Loft-house to Pateley Bridge, and it’s one third-gear bend after another, holding 3,500rpm, and it’s more entertaining than it’s got any right to be. It’s not a stiff chassis exactly, and I should think that, torsionally, it’s quite flexible, but nevertheless it does go exactly where I want it to. One of the most outstanding plus points is that it’s driver-friendly: you can do virtually anything you want with it. It’s not over-powered, and handling is adequately compliant. The 924 Turbo is an easy-going car, once you’ve got used to the seating position, pedals and so on. It’s biddable, has no tricks up its sleeve, goes the way you point it, and, in the context of a car from the mid-1970s, it may lack the panache of a 911 but nonetheless is a character in its own right.

924 CARRERA GT 1980–1982

Layout and chassis

Steel body, composite wings, two aluminium seats, hot-dip galvanized shell, polyurethane extremities, top-mounted air scoop for intercooler

Engine

924 CARRERA GT

The 924 Carrera GT is probably the most desirable of all Porsche’s front-engined water-cooled models, being a limited production run as well as having a racing pedigree. Launched in the white heat of the Turbo era, it recalls the marque’s remarkable performance at Le Mans in 1980, when three Carrera GTs that bore close resemblance to cars you could buy in the showroom finished sixth, twelfth and thirteenth overall.

Unveiled as a styling exercise at the Frankfurt Show in September 1979, the 924 Carrera GT was an evolution of the 924 Turbo – and designated factory type number 937. The bodykit is unpretentious, as the car was intended for competition work, produced in sufficient numbers for homologation into Group 4, leading into the Group B supercars that would take over in 1982. According to Porsche’s chief race car tester, Jürgen Barth, there was initially no factory interest in racing its front-engined cars, but he and co-engineer Roland Kussmaul were allowed to do their own thing with some 924 Turbo prototypes. The Le Mans cars of 1980 stemmed from there.

Visually, the 924 Carrera GT stands out because of its plastic front wings and wheel spats – and that distinctive bonnet air scoop. Under the skin, what makes it special is the intercooler that the ordinary 924 Turbo didn’t have, riding on a stiffened and lightened platform to provide handling at the raw edge. We know that Porsche are past masters at creating these race-derived special editions – and the 924 Carrera GT is worthy of the same degree of respect as the revered 911 Carrera 2.7 RS from 1972, as the resulting sports car is something of a technical tour de force that’s evolved from the series production model.

The Frankfurt show car was developed into the limited-production 924 Carrera GT released in June 1980, coinciding neatly with the success at Le Mans – Jürgen Barth and Manfred Schurti came sixth overall in an era when the slant-nose 935 and (winning) mid-engined 936 were dominant. Two versions were available: the road-legal production run of 406 units of the standard GT, which enabled the homologation process – of which six were prototypes; and the GTR, based more closely on the works Le Mans machines, which would metamorphose into the full-on GTR and GTS Rally competition cars the following year.

The street car was equipped with the 924 Turbo engine, augmented by an air-to-air intercooler lying flat on top of the engine’s cam cover and served by the dedicated air scoop. It developed 210bhp at 6,000rpm, which may not be a wildly increased output, but the car derived its punch and its raw character from a good power-to-weight ratio. This was achieved by omitting superfluous sound-deadening and swapping narrow steel front wings for broad-shouldered polyurethane and glass-fibre composite panels, and trading the steel doors and bonnet for aluminium skins. The front spoiler, outer sills and rear wheel-arch extensions were also in flexible polyurethane, reinforced with glass-fibre. Although the characteristic 924 Turbo vents in the front of the bonnet were retained, the Carrera GT had a single long horizontal slot at the base of the front spoiler. There was also a larger rear spoiler on the outer rim of the tailgate. It also used an aluminium transaxle tube and lightweight suspension components in a firm-riding recipe that included Bilstein dampers and stiffer springs.

In the cabin, still recognizably that of the 924 with its two-plus-two ergonomics, there are lightweight 911 SC sports seats, upholstered in black cloth with a red pinstripe (although one customer specified a full-leather interior). The Carrera GT tips the scales at just over 1,000kg (2,200lb), undercutting the normal 924 Turbo by 181kg (399lb). This, combined with the punch from the intercooled turbo engine, enables a top speed of 240km/h (150mph) and a 0–100km/h time of 6.9sec. By comparison, the normal 924 Turbo produces 177bhp and makes 204km/h (127mph) tops, with 0–60mph coming up in 9.2sec.

TypeFront-mounted, in-line slant-fourBlock materialCast ironHead materialAluminiumCylinders4CoolingWater-cooledBore and stroke86.5 × 84.4Capacity1984ccValvesSOHC, 2 valves per cylinderCompression ratio8.0:1CarburettorElectric pump, Bosch K-Jetronic injection, KKK turbo, Langener & Reich intercoolerMax. power (DIN)210bhp at 6,000rpmMax. torque303lb ft at 6,000rpmFuel capacity80ltr (17.6gal)Transmission

GearboxGetrag manual 5-speed, transaxle rear drive, limited-slip differential optionalClutch911-type single dry plateRatios1st 3.6712nd 1.7783rd 1.2174th 0.9315th 0.706Reverse 2.909Final drive4.125Suspension and Steering

FrontMacPherson struts, coil springs, anti-roll barRearTrailing arms, torsion barsSteeringRack and pinionTyres205/55VR × 16 front, 225/50VR × 16 rearWheels16in Fuchs alloysRim width7 J × 16 front, 8 J × 16 rearBrakes

TypeFront and rear ventilated and drilled discsSize30mm all roundDimensions

Track1,420mm (55.9in) front, 1,389mm (54.7in) rearWheelbase2,402mm (94.6in)Overall length4,200mm (165in)Overall width1,685mm (66in)Overall height1,270mm (50in)Unladen weight1,080kg (2,380lb)Performance

Top speed241km/h (150mph)0–60mph6.9secThe 924 Carrera GTS and GTR

The evolution of the 924 Carrera GT logically encompasses its two derivatives: the GTS and GTR. In March 1981, the two offshoots came out once the construction of the road-going Carrera GT run was complete for homologation purposes. Although the GTR and GTS are primarily competition cars, with headlights lurking behind Plexiglass fairings rather than the parent car’s pop-up type, a number were adapted for road use and finished with full cabin furnishings and wind-up windows instead of the sliding Plexiglass type. Glazing is thinner than standard-issue 924 panes. In addition, they have 911 seats instead of the racer’s 935-style racing buckets.

The 924 Carrera GTS and its GTR sibling are evolutions of the 924 Carrera GT, introduced in March 1981. Headlights are mounted behind Plexiglass fairings, rather than the parent car’s pop-up type. This particular car was owned by the late racing driver Richard Lloyd, who drove a 924 GTR at Le Mans in 1982 and was known to the author through his motorsport PR business, but was killed in a light plane crash in 2008.ANTONY FRASER

The 924 Carrera GTS’s broad-shouldered polyurethane and glass-fibre composite wheel arches replaced the standard 924 Turbo’s narrow steel panels, and the steel doors and bonnet were exchanged for aluminium skins. The front spoiler and outer sills were also in flexible polyurethane, reinforced with glass-fibre.ANTONY FRASER

The Carrera GTS delivers better low-speed torque than the GT by deploying a maximum 1.0 bar turbo boost to produce 245bhp via a 40 per cent limited-slip differential, easing ahead of the Carrera GT with a 0–100km/h time of 6.2sec and a top speed of 249km/h (155mph). Being a race and rally machine, its suspension is uprated with lighter front wishbones and coil-sprung rear suspension, enhanced by cast aluminium trailing arms. In rally trim, the GTS features yet tougher suspension – with higher ground clearance, plus a sump guard and underbody shield and a built-in roll-cage. Brakes are ventilated cross-bored discs all round, allied to 911 Turbo hubs. It’s 59kg (130lb) lighter than the Carrera GT by virtue of glass-fibre wings, air dam and rear bumper, as well as doors and bonnet. Wings and rear arches are also more prominent than the Carrera GT’s. The rear greenhouse panel is in Plexiglass, although roadable versions have the normal glass tailgate with a wiper.

A 280bhp version, described as the GTS Rally or Club Sport, became available from January 1981 – stripped for action, with no protection below the floorpan and an aluminium roll-cage and fire extinguisher inside. Famous owners of this beast over the years include Derek Bell, Lord Mexborough, the Earl of March and George Harrison.

Lighter still, the GTR model – R for Rennsport (racing) – was intended for use in the FIA Group 4 category, where it was eligible for the 1982 World Endurance Championship. It’s no surprise that it was directly descended from the 1980 Le Mans car, weighing in at 945kg (2,084lb). But the output is quite staggering. The much-modified 2.0-litre 924 Turbo power unit delivers a serious 375bhp, thanks to Kugelfischer mechanical fuel injection and a larger KKK turbocharger, now housed on the left-hand side of the engine block instead of below and to the right front. It could hit 291km/h (181mph) and top 100km/h in 4.7sec. Brakes were sourced from the 935 race car, having originated in the 917. When new, you could specify any colour you liked for the GTR, provided it was white. Relative to the basic 924 Turbo’s £13,998 – and even the Carrera GT’s £19,211 – the £34,630 price tag in 1981 was stratospheric. By comparison, the (red only) GTS would set you back a not unreasonable £23,950, relatively speaking.

Contrast this with the showroom sticker of £18,180 for a Sport Equipment 911 SC at the time, and the status of the 924 Carrera GT in the marque’s hierarchy becomes a little clearer. Of the 406 units of the 924 Carrera GT, just seventy-five were in right-hand drive, with UK deliveries starting in January 1981. There were just forty units of the GTS and nineteen of the GTR, all of which were left-hand drive.

Bodywork and Chassis

The GTS and GTR panels were of glass-fibre rather than polyurethane. These more extreme cars were fitted with a one-piece nose section with integral lights and rubber overriders – and no front bumper. The contours of the front wheel arches are slightly wider in the GTS/GTR than the Carrera GT, and the back ones are a tad taller, as well as wider. Their glass-fibre tailgate spoilers are slightly different to the GT’s, with a built-in Gurney flap lip and a moulded GTS logo beneath.

The Porsche badge is a decal glued on the bonnet, although some owners opt to site the number plate there instead. In all cases, the windscreen is bonded to the shell, rather than rubbered in place, improving the airflow over the cabin top. If you’re looking at a car with a big ‘step’ between the frame and the glass, its screen isn’t bonded, so it may not be genuine. There are fundamental changes in the rear chassis as well, to do with the use of coil springs requiring variable ride-height platforms. The boot floor is also raised to make provision for a 120-litre (26.4gal) fuel tank to provide suitable range for endurance racing, so there are no rear seats. In addition, the Carrera GT has a slightly extended rear bumper, projecting further than the 924 Turbo’s, and a larger-lipped wrap-around tailgate spoiler with a rougher surface finish. It comes in just three body colours: Diamond Silver metallic (twenty-two UK cars), Black (twenty) or Guards Red (thirty).

Here’s how the chassis numbering works. The factory’s model designation is 937, so the VIN number stamped on the left of the false bulkhead should read WPOZZZ93ZBN7… and so on. The 93 serves to indicate 937; the letter B is the factory code for 1981, and the N identifies it as a car built at the Audi plant at Neckarsulm, north of Stuttgart. The numerology should be followed by two zeros and a three-digit number corresponding to its positioning in the 406-unit production run. The first chassis number was 066 and the last 449. By comparison, a 924 Turbo is type number 931 and will have a VIN containing 93ZBN1. The GTS VIN should read WPOZZZ93ZBS7…, the S referring to its Stuttgart construction, then 10001 to 10059 depending on its place in the production chart. As a separate production run, the GTR chassis identification ran from 93ZBS720001 to 0022, with numbers 13 and 18–21 omitted.

In all cases, the swirling Carrera script is emblazoned on the top of the right-hand front wing, with the Carrera GT identification to the right of the rear panel. The cursive turbo label appears on the inner door sills. When checking out a car, examine it closely for ill-fitting panels and odd gaps suggesting poor accident repairs. Check for over-spray on hard-to-mask areas such as the suspension. The plastic panels will almost certainly have ripples, which is not a concern, but look underneath to see if the underbody protection has been compromised.

The Interior

Creature comforts and amenities in UK-spec cars include 911 SC sports seats, deep-pile carpet, electric windows, Panasonic radio/cassette player (model number CQ863) with electric aerial, tinted glass, driver’s door electric/heated mirror, rear wiper, headlamp washers and four-spoke sports steering wheel. Again, the GTS is in a different league: it has the three-spoke 911 SC wheel, racing bucket seats and four-point harnesses. Door trims are unique, with grab handles instead of door-pulls and flimsy catches. Bonnet cables have been known to fail. Only the principal moulding remains of the original 924 dashboard, its binnacle containing the 300km/h (186mph) speedo and rev-counter with integral boost gauge, while other dials are mounted in a centre console ahead of the gear lever. Apart from a thin veneer of black carpet, all other trim is absent. The downside is that none of the specialized interior trim is available any more.

Being a competition-oriented machine, the 924 Carrera GTS cockpit harbours a comprehensive roll-cage and fire extinguisher, while the author is belted into the bucket seat with a full Autoflug harness.ANTONY FRASER

The Engine

The 924 Carrera GT uses the 924 Turbo engine, with the same Porsche-designed aluminium cylinder head (and cast-iron block) but modified combustion chambers, 3mm larger exhaust valves and repositioned spark plugs relative to the standard car. The electronic ignition system is more refined, and it’s fitted with forged pistons and an air-to-air intercooler mounted over the rocker cover. The KKK (type K26-2660 GA 6.10) turbo has a slightly larger body – and its maximum boost pressure is 0.75 bar, so output is up to 210bhp at 6,000rpm. It runs two auxiliary cooling fans instead of just one, although the water radiator is identical. The oil cooler is relocated ahead of the radiator, and the larger-bore exhaust is more of a straight-through system.

The weakest link is the turbocharger – it has a startlingly short 40,000- to 64,000km (25,000- to 40,000-mile) life expectancy. The engine should always be allowed to run for a couple of minutes before switching it off, to allow the oil to circulate and the compressor to cool off. Otherwise, oil cooks in the turbo and there’s none available for the bearings on start-up. The engine should also be allowed to warm up for a few minutes before pulling away, to let the lubricant coat the bearings effectively.

Despite its competition tendencies, the 924 Carrera GTS cabin is also a comfortable environment, offering carpeted floorpan, padded bucket seats and the normal range of early 1980s controls and instrumentation.ANTONY FRASER

Just when you think you’ve got the hang of the Carrera GT, you discover the GTS is quite different in many ways. For instance, instead of the intercooler, pride of place under the bonnet goes to the cast-alloy inlet manifold, fronted by the modified injection system from the Porsche 928, which supplies the injectors via an eight-into-four adaptor stack. The massive intercooler is tucked up in the front of the car, and there’s an unconnected safety cutout switch on the inner wing in front of the VIN plate. The battery is positioned in the boot for optimum weight distribution – and there’s a hand-made light-alloy expansion tank for the cooling system.

Suspension, Gearbox and Brakes

The most noticeable difference between the 924 Turbo and the Carrera GT is the dog-leg first gear, located to the left of the gate, so the main four ratios are selected in an H-pattern and convenient for competition use. Reverse is ahead of first. The G31/03 five-speed gearbox is of the transaxle type, in unit with the rear axle for optimum weight distribution. Compared with the 924 Turbo, it has a stronger final drive, and case-hardened crown wheel and pinion in third, fourth and fifth gears. The actual ratios are the same as for the 924 Turbo, although first gear synchro is out of the 911 for easier shifts when cold, along with a 911 clutch. The limited-slip differential is optional. On the GTS the finned transaxle has its own minimalist oil cooler beside it. Check that the casing isn’t leaking on prospective cars.

The Carrera GT sits 10mm (0.4in) lower than the 924 Turbo, and uses Bilstein gas dampers. The steering joints are beefed up, as are the anti-roll bars and rear trailing arms. Brakes are ventilated discs measuring 392mm (11.5in) up front and 290mm (11.4in) at the rear, with dual brake circuits front and rear, allied to a stepped tandem master cylinder. There are two ducts within the front valance to cool the front discs. The brake circuit is split front/rear, while that of the 924 Turbo is a diagonally split twin-circuit system.

Wider wheels give the 924 Carrera GT a broader track than the 924 Turbo, which accounts for the bulbous wings and wheel arches in the first place. Track, both front and rear, measures 1,477mm (58in), including 21mm spacers at the rear. Wheels are forged five-spoke Fuchs, 7J × 15in shod with 215/60 VR15 tyres front and rear, while 7 and 8J × 16in wheels with 225/50 VR16 rear tyres were an optional fitment – and standard on the GTS Rally or Club Sport model.

Although the characteristic 924 Turbo vents in the front of the bonnet were retained, the Carrera GTS also had a large intake where the standard model’s NACA duct would have been, plus a single long horizontal slot at the base of the front spoiler.ANTONY FRASER

Performance

On the road, the Carrera GT offers a vivid driving experience. When the turbo kicks in it’s creamy smooth – and after 3,000rpm it pulls like a train. Up to a point, there’s so much torque available that you can (almost) get away with treating it like a four-speed gearbox and forget about first, although second is frequently difficult to find. Handling is neutral, with a hint of understeer, and the car drifts rather than the back end coming out at speed. The brakes are the weakest link – they feel like early 1980s brakes and, although they do the job, they don’t match the car’s performance. The steering is high-geared, as well, which makes over-correcting a temptation. It’s a fast, well-balanced driver’s car – reliable, economical (returning 9.4ltr/100km or 30mpg) and easy on tyres.

Alongside the 260km/h (160mph) speedometer, the revcounter is oriented to provide an unrestricted view of the dial from 3,000rpm to 6,000rpm beneath the rim of the non-adjustable steering wheel. The turbo emits a characteristic whistle just below 2,000rpm and the boost gauge in the base of the rev-counter starts to register at 2,500rpm with 0.5 bar, rising to 1.2 bar around 3,000rpm when torque peaks – and there it stays. Lag is minimal. There’s a surge of power at 3,500rpm, complemented by a change in the exhaust note as it comes on full song.

It’s a fast A-road car, provided it’s not too crowded, and highly entertaining on smooth-surfaced B-roads and back doubles, when an incautious right foot makes you conscious of its depths of power. Handling is spot on, as you would expect from such a well-honed package, incorporating positive scrub-radius front-suspension geometry that provides all the front-end grip you need to tackle fast corners. Track-day buffs say it’s as fast as a Boxster on the straights, but loses out on the bends. Put that down to the march of time. It’s a racer for the road, yet at the same time it’s kitted out like its more civilized siblings. The only thing it doesn’t do well is town-centre parking, as it hasn’t got power steering.

Le Mans Legends

The inspiration for the 924 Carrera GT came from the factory’s Le Mans entries in 1980, when the three cars developed under Norbert Singer by Jurgen Barth and Roland Kussmaul completed the marathon event, vindicating the decision to go racing with the front-engined water-cooled model.

Financed by the Porsche concessionaires in Germany, USA and the UK, Barth and Manfred Schurti drove the German car to finish sixth overall and third in the GTP class, averaging 179.6km/h (111.60mph) over 4,310km (2,678 miles). Al Holbert and Peter Gregg drove the American car to thirteenth place, despite a dropped exhaust valve, and Derek Bell, Tony Dron and Andy Rouse handled the British car to twelfth, requiring just a change of spark plugs but experiencing the major drama of losing its one-piece nose cone at night in the turbulence of a passing 935 on the Mulsanne Straight. The following year, Barth/Röhrl came seventh in their 924 GTR and Schurti/Rouse were eleventh, but the Alméras/Sivel car retired with transmission failure. In the rally arena, Walter Röhrl won the 1981 German Rally championship in a 924 Carrera GTS, with the Hessen Rallye, Rallye Vorderpfalz and the Serengeti Safari Rallye to his credit.

Walter Röhrl discusses a seat fitting with Jürgen Barth and Roland Kussmaul at Weissach during the construction of the 924 Carrera GTRs in 1979–80.PORSCHE PHOTO ARCHIVE

DEREK BELL INTERVIEW

Derek Bell has never really stopped racing. His frontline competition career spanned more than two decades, including an F1 stint at Ferrari and five Le Mans wins, culminating twice in the World Sportscar Championship title. He can be relied upon to drive any front-line car at any major historic meeting, from vintage Bentley to classic Mustang, Classic Le Mans and Copenhagen Historic GP. Derek is a legend, and certainly one of the most successful drivers in history. And much of that was achieved in Porsches. We chatted with him in a rare downtime moment when he wasn’t gunning some supercar up the Hill at the Goodwood Festival of Speed.

Having enjoyed a long and successful association with Porsche, Derek Bell owns a 924 Carrera GTS, while his daily drive is a 991.ANTONY FRASER

Johnny Tipler: I believe you have a modern 991 at the moment?

Derek Bell: Yes, I do; I’m part owner of the Bentley and Porsche dealership in Naples, Florida, so I have to cross the Alligator Alley on a weekly basis, and I’m always there if I’m in America. And I can’t afford to buy a Bentley but I can afford to buy a 991, so I bought a 991. Plus, the 991 is the sort of fun car that, when you’re driving on a dead straight bit of road like Everglades Parkway it’s not as boring as it might be in a bigger car, which cruises very beautifully at 80mph (130km/h); a 911 has a bit more character to it at that point.

JT: You raced a 924 Carrera GTR, a 934 and a 935, but did you ever get to race a 911 RSR?

DB: I once raced a 934 and a RSR for the same team in the same race at the Nürburgring in 1976, which was rather exciting because I got out of one and they stuck me in the other – that was Max Moritz Racing – and I was happy enough in the 934, which was turbocharged. Then they put me in a regular Group 5 RSR, and a normally aspirated 911 is much more fun to drive than the 934 turbo because it’s such a handful when all the power comes in. The following year I drove a 935 for Georg Loos (GELO Racing) and also with that the power doesn’t come in gently, one might say!

JT: Even though you’ve got those massive wheels and tyres on the back?

DB: Yep, at the Nürburgring, with 160 corners, you spend so much time leaping and jumping over the crests, and when you touch the ground you want it to be progressive and not suddenly go up from 350 to 550 horsepower during that split second you’re in the air. And also the 934 was never built to be a proper race car, though you’ll probably think it was, but it’s not like a 935 that was built from the ground up as a race car and really was a proper car for the job. Oh yes, it was certainly a racing car, the 935. It’s a car you get in and get hold of the gear lever, which sticks up like a mast, and you say to the car, ‘It’s either you or me, but today it’s me,’ and you would have to convince yourself that you’re going to beat the hell out of it, or it will beat the hell out of you. You are actually fighting it and you’re saying, ‘I’m in charge today, not you,’ and that has to be your attitude, you have to be ahead of it the whole time. It wasn’t scary, it was just magnificent.

JT: To go back slightly, your first race in any Porsche was in a 917 at the 1971 Buenos Aires 1,000km with Jo Siffert.

DB: Which I won!

JT: That’s quite incredible. But you were trying out long-tail bodywork on the 917 for them at Hockenheim during the preceding winter.

DB: That came about after John Wyer Automotive tested at Goodwood with me, Ronnie Peterson and Pete Gethin in the 917, and for some reason I got the contract to drive for them, probably because Ronnie had his eyes on Formula 1 and that’s where he should have been, and I’d had my couple of years in Formula 1 with Ferrari. Of course Pete Gethin was also getting in there as well, but I always thought I was as good as Peter, though I thought Ronnie was a star, which of course he was. So, I got the drive and then I did the test at Hockenheim in the pissing rain at Christmas in the dark, nearly, which was actually really very unfunny, and from there of course we went straight to Buenos Aires in January.