Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

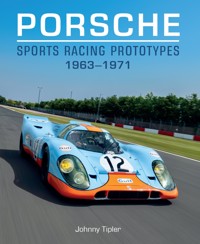

Between the 1950s and 1971, the halcyon days of long-distance endurance motor racing, Porsche embodied the up-and-coming manufacturer, progressing inexorably from reliable class-winner to outright victor – a platform they consolidated and never rescinded. This book focuses on the six distinct Porsche models that raced from 1963 to 1971. Porsche created a series of racing cars – the 904, 906, 910, 907, 908 and 917 – to run in the FIA-regulated International Sports Car Championship Group 6 Prototype class, the Group 4 World Sportscar Championship, and European Hillclimb Championship events held during that period. These races lasted either 24 hours, 12 hours or 6 hours, or were categorised by distance: 1,000km, 500km or 500 miles. Events took place annually at European tracks including Le Mans, Nürburgring, Monza, Spa-Francorchamps and Brands Hatch, and in the USA at Daytona and Sebring. Chronicling each season, this visually stunning volume records Porsche's multitude of successes. With over 300 outstanding images, many previously unseen, including professional photos and factory archive pictures, and featuring interviews with heroic Porsche racing drivers – with the Foreword written by two-times Le Mans winner Gijs van Lennep – this book tells the thrilling story of Porsche's rise from consistent class-winner to incontrovertible outright victor.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 423

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The 908 LH of Claudio Roddaro takes the chequered flag at the 2018 Le Mans Classic.

The 906 could legitimately be used on road and track, and over the years many, such as this, running in the Dordogne in 2007, have featured on the Tour Auto Optic 2000.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Timeline

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 THE PORSCHE 904 CARRERA GTS 1963–66

CHAPTER 2 THE PORSCHE 906 ‘CARRERA SIX’ 1966–67

CHAPTER 3 THE PORSCHE 910 1966–68

CHAPTER 4 THE PORSCHE 907 1967–68

CHAPTER 5 THE PORSCHE 908 1968–71

CHAPTER 6 THE PORSCHE 917 1969–71

Acknowledgements

Appendix: Specifications

Index

FOREWORD By Gijs van Lennep

Gijs van Lennep is an ambassador for Porsche, snapped here at Classics at the Castle with a 991 50th Anniversary model.

F irst of all, I would like to say how pleased I am to endorse Johnny Tipler’s book about the era of motor racing when Porsche was in the ascendant, which was also the period when I was building my racing career – the bulk of which was spent driving Porsches – and which culminated in two wins at the Le Mans 24-Hours in 1971 in a 917 and 1976 in a 936.

My racing career even took off in a car that was distantly related to Porsche: I started competing in a tuned-up Volkswagen Beetle at Zandvoort, which is within earshot of my home at Aerdenhout in the Netherlands. I scored my first win in 1965 in a Porsche 904, which sets the scene nicely for the content of this book.

I raced examples of all the models covered in the book, including the 904 Carrera GTS, the 906, the 908 Spyder and the 917, and each one was a milestone on Porsche’s trajectory to the top of the endurance racing pyramid. I enjoyed several successes in the 906, 908/2 and various 911s, and I won the inaugural Porsche Cup in 1970, organised on the initiative of Ferry Porsche and awarded to the world’s best privateer driver. Also in 1970, I drove the 917 KH owned by the Finnish driver Antti Aarnio Wihuri, alongside David Piper. At Le Mans, we dropped out on lap 112 when I had a tyre blowout at 320km/h, from which I luckily emerged totally unscathed. Nevertheless, the 917 was a fantastic racing car, and I like to say that it handled like a very powerful go-kart! I’m told that no one else drove 917s more than I did, and in the 1971 Le Mans, I drove one of the Martini Racing Team’s 917 KHs together with Helmut Marko. We hardly had any brakes for the last five hours, but stopping for fresh pads and so on would have cost us the lead. While most drivers went off for a doze during their downtime, during one of my breaks from driving, I tucked into a hearty steak dinner. That may have been a bit unorthodox, but we were young and didn’t know any better. In fact, in that race, we set a speed and distance record for the 24-hours, and the distance one wasn’t broken for 39 years.

I first met Johnny around 1973 when I was driving one of Frank Williams’ Iso-Marlboro F1 cars and he was doing John Player Team Lotus PR, promoting JPS cigarettes in the Formula 1 paddocks and press offices during the Grands Prix. Subsequently, our paths have crossed many times, such as when I drove a 356 in La Carrera Panamericana, a 550 Spyder in the Mille Miglia, and a 917 Can-Am car at the Zandvoort Historic Grand Prix, and he was there too, covering those events as a journalist. We’ve had plenty of fun at Abbeville racetrack over the years, too, where our mutual friend, RS collector Johan Dirickx, lets me put some of his rare 911 RSs through their paces around the circuit.

So, I’m very happy to be contributing to this book about the 1960s Porsche race cars, a subject that I have always been passionate about, and as a marque ambassador, I continue to endorse the brand at events such as the 2023 Rennsport Reunion at Laguna Seca. All being well, you will read about more of my racing exploits further on in the book!

TIMELINE

1963

Type 904 coupé introduced for the 1964 racing season.

1964

Type 904 GTS competes in the International World Championship for Makes, winning mountainous Sicilian Targa Florio epic.

1965

Types 904/6 and 904/8 coupés introduced, powered by flat-4 Carrera and ex-718 F1 flat-8 engines. Lightweight open-top Känguru prefigures Types 906, 910 and 909 Bergspyder hillclimb cars.

1966

Type 906 coupé launched, with 2.0-litre flat-6 engine; eligible for FIA Group 4 and Group 6 categories. Designed by Helmuth Bott and Hans Mezger; long- and short-tail versions raced. Targa Florio is biggest win. Aerodynamically-improved Type 910 introduced, current for the following two seasons. Type 910 Bergspyder entered in European Hillclimb Championship.

1967

Type 907 coupé with 2.2-litre flat-6 engine launched at Le Mans, heralding Porsche’s concerted attack on the World Sportscar Championship. New Type 711 3.0-litre flat-8 engine introduced. Type 910 wins Targa Florio.

1968

Type 908/1 coupé introduced, using 3.0-litre flat-8. Type 908 Bergspyder wins European Hillclimb Championship. Type 907 wins Targa Florio.

1969

Type 908/2 Flounder introduced with open-top Spyder bodywork, powered by 3.0-litre flat-8. Another Targa Florio victory. Mentored by Ferdinand Piëch, Type 917 introduced, powered by 4.5-litre flat-12 engine, using both long- and short-tail rear bodywork. Type 917 PA Spyder races in Can-Am series. Porsche wins FIA World Championship for Makes (World Sportscar Championship) in 1969, 1970 and 1971.

1970

Type 908/3 introduced, featuring compact Spyder shell and 3.0-litre flat-8 engine; victory in Targa Florio. Porsche competition programme divided between JW-Automotive and Porsche Konstruktionen. Type 917 victorious in Le Mans 24-Hours. Flat 12 engine capacity increases to 4.9- and 5.0-litres.

1971

Competition programme run by JW Automotive and Martini International Racing teams. Types 908/3 and 917 win eight out of eleven rounds of the FIA World Sportscar Championship – also known as the World Championship for Makes.

INTRODUCTION

W hat is so significant about these seemingly random eight years between 1963 and 1971? Almost six decades ago, they represented the era when Porsche methodically worked its way up the endurance racing ladder from class winner to outright victor. We take the company’s success pretty much for granted now, in the showroom as well as on track. The period that the book focuses on reveals the skills, determination, ambition and prowess that consolidated the marque’s already burgeoning reputation.

In many ways, they were the halcyon days of long-distance endurance motor racing, during which Porsche embodied the rise of the up-and-coming manufacturer, progressing inexorably from reliable class-winners throughout the 1950s and 1960s to outright victors – a platform they consolidated and never rescinded. This does not imply that they were in any way also-rans in the lead-up since anyone running a Porsche, whether factory or privateer, was a serious contender at any level of the sport from the word go.

Like Colin Chapman of Lotus Cars, Porsche started off as a car maker in 1948, and the two makes often vied for victory in the sports car classes over the following decade. While Lotus focused mainly on producing and running single-seater racing cars from 1958, Porsche concentrated on sports racing cars, dipping into F1 and F2 with the Types 718/2 and 804 between 1959 and 1962, though majoring on the 718 RSK Spyder, RS61 and Type 695 2000 GS Abarth in sports-GT racing. It is interesting to draw a parallel between the two marques since both manufactured road-going sports and GT cars and, of course, Team Lotus won the F1 World Title four times during this period in which we are exploring Porsche’s rise to the top. Like Enzo Ferrari, Lotus founder Colin Chapman built production cars to subsidise the company’s racing activities, while Porsche raced in order to market its sports car production. It is no disrespect to Lotus to remark that the 75-year-long histories of both companies suggest that Porsche constructed the better business model. Chapman had no time for rules: he comprehended them and found ways to exploit loopholes – the ‘unfair advantage’, as he put it. Porsche, on the other hand, played with a straight bat. So, while Team Lotus was often the trailblazer in the rarefied field of F1 and single-seater racing cars, the sports-racing prototype arena in which Porsche competed was dominated by Ferrari, who was challenged over much of the 1960s – and beaten – by the corporate might of Ford. The eponymous Hollywood movie casts this needle match rather well. And as the titans wore each other down, Porsche capitalised on their rivalry and had eclipsed them by 1970.

The work’s 907s of Gerhard Mitter/Lodovico Scarfiotti, Jo Siffert/Hans Herrmann and Vic Elford/Jochen Neerpasch roar away from the startline to begin 1968’s BOAC 500 enduro.

I have been infatuated with Porsches since I was a child, initiated by an incident in the early 1960s involving my father spinning backwards into a hedge in his friend’s 356, fortunately without incurring injury or significant damage to the car. One could keep track of Porsche’s performances on track and in rallies via the motor racing magazines and a neat annual publication entitled Castrol Achievements. That’s why I have always been fascinated by the epoch that encapsulates the subject matter covered here.

I have interspersed the specification of the cars with their performances in accounts of the World Championship races they participated in, mostly chronologically, dovetailing interviews with some of Porsche’s top drivers who helped define this fabulous epoch. The book focuses on the six distinct Porsche models that raced during this period. Obviously, and inevitably, there were overlaps, for instance as Porsche tried out a new model whilst the existing one was still being campaigned, but, more or less, each car falls conveniently into each year.

Between 1963 and 1971, Porsche created and honed a series of racing cars in its Zuffenhausen factory and Weissach competitions department to run in the International Sports Car Championship Prototype classes. These cars are synonymous with the Le Mans 24-Hours and the rest of the FIA-regulated thirteen-round World Sportscar Championship races held during that period, split between the International Manufacturers’ Championship and the International Sports Car Championship. The category is known today as the World Endurance Championship; these races lasted 24 hours, twelve hours, or six hours, or they were otherwise categorised by distance, usually run over 1,000km or 500km, or indeed 500 miles. According to the FIA calendar, events took place annually at various European tracks, including Le Mans, Nürburgring, Monza, Spa-Francorchamps and Brands Hatch, among others, and in the USA at Daytona and Sebring.

With the 917 KH (#023, pictured at the factory in 1970) Porsche finally achieved its ambition of winning the Le Mans 24-Hours.

Here in the Brands Hatch paddock, the 2.2-litre 907 LH of Hans Herrmann and Jochen Neerpasch came 4th in the 1967 BOAC 500.

THE WORLD SPORTSCAR CHAMPIONSHIP

The World Sportscar Championship that Porsche zealously contested virtually throughout was an endurance race series, running under several different guises from 1953 to 1993. The series’ official name changed from time to time, variously to the Sportscar World Championship, the World Endurance Championship, the World Championship for Makes – or Manufacturers – and the World Sports Prototypes Championship.

The first era dates from 1953 to 1961, with six or so races each season in which sports prototypes and GT cars competed, exemplified by works entries from Ferrari, Maserati, Mercedes-Benz, Aston Martin and Jaguar, though the latter only ran at Le Mans. The 2023 movie Ferrari, starring Adam Driver and Penélope Cruz, encapsulates extremely well the drama of the duel between Ferrari and Maserati in 1957.

From 1962 to 1965, the FIA grouped GT cars into three categories with separate classifications, while hillclimbs and sprints expanded the championship calendar to fifteen races a year. The points system did not paint an accurate overall picture of the most significant results, so from 1966, the FIA reverted to a programme of between six and ten races, with events including the Le Mans and Daytona 24-Hours and the Targa Florio, Monza, and Nürburgring 1,000kms counting towards the Groups 4 and 5 sports-prototype championship. The crucial year of the Homeric contest between Ford and Ferrari was 1966, captured with varying degrees of veracity in the eponymous 2019 movie. The no less significant supporting cast included Porsche, Lola, Chevron, Matra, Alpine, Alfa Romeo, Chaparral and Howmet, not forgetting the AC ‘Daytona’ Cobras, Ford-Cosworth F3L and the odd Maserati. There was also a separate classification for GT cars between 1968 and 1975, though the swingeing rule change for 1972 that outlawed the 5.0-litre sports cars such as the Porsche 917 and Ferrari 512S saw Porsche withdraw officially, with Ferrari dropping out in 1973 and Matra in 1974.

The Type 910 #28 driven by Jo Siffert and Hans Herrmann in the 1967 Nürburgring 1,000Kms failed to finish due to a dropped valve.

Long-distance endurance races such as the Le Mans 24-Hours inevitably include nocturnal running, demonstrated by this 917 at the 2012 Classic event.

KEY EVENTS

Le Mans 24-Hours, 1953–Mille Miglia, 1953–57

Nürburgring 1,000kms, 1953–

RAC Tourist Trophy, Dundrod/Goodwood/Oulton Park, 1953–69

Sebring 12-Hours, 1953–

La Carrera Panamericana, 1953–54 Targa Florio, 1955–73

Monza 1,000kms, 1963–2008

Spa-Francorchamps 1,000kms, 1963–

Reims 12-Hours, 1964–65

Buenos Aires 1,000kms, 1954–72

Zeltweg-Österreichring 1,000kms, 1966–76

BOAC 500 miles/1,000km Brands Hatch, 1967–71

Norisring 200 Miles, 1984–88

Watkins Glen 6 Hours, 1968–71, 1973–80

In 1976, a separate championship for GT and new Group 5 silhouette cars was introduced, ushering in the 911 Carrera RSR Turbo-based Porsche 935 that became almost ubiquitous over the following eight or nine years. Prototypes were readmitted in 1979, followed by the Group C category, which was synonymous with the FIA’s World Endurance Championship from 1982 to 1985, the World Sports-Prototype Championship from 1986 to 1990, and the World Sportscar Championship from 1991 to 1992. Several international manufacturers built Group C cars, including Porsche, Ford, Lancia, Jaguar, Nissan, Mazda, Toyota, Aston Martin and Peugeot. The most successful marque contesting the World Sportscar Championship was Porsche, who gained the most titles, followed by Ferrari.

PORSCHE LINE-UP

Over this halcyon period, the Porsche models involved in the action ranged from the Types 904 GTS (1963–66), the 906 – also known as the Carrera Six – (1966–67), the 907 (1967), the 908 (1968–71), the 909 Bergspyder (1968), the 910 (1967–69) and the 917 (1969–71). I consider it to be the era of the most aesthetically attractive sports racing cars, too – swooping curvaceous shapes unadorned for the most part by aerodynamic extravagances apart from modest split-ters, spoilers and gurney flaps.

Different models of Porsche were demonstrated at the 2012 Solitude Revival, including this 908/1 coupé, 910 and 917.

The 904 GTS

This was a radical departure from Porsche’s previous construction methodology, being entirely fibreglass-bodied on a traditional steel ladder-type chassis (rather than a multi-tubular spaceframe), powered by the 4-cylinder flat-4 2000cc 718/RS competition engine. A small number received the 6-cylinder unit introduced with the 911 road car in 1964 – still billed as the 901 in 1964. As well as the factory race team, the 904 was mostly raced by private entrants such as Dutch VW importer Ben Pon. Probably 108 units were built, including two flat-8 prototypes that utilised the 8-cylinder engine from the Type 718 Grand Prix cars.

The 904 also marked the passing of Porsche’s 1955 4-cyl-inder Carrera engine that had brought so much success in cars such as the 550 Spyder, RS60 and RS61 and 356 Carrera Abarth. Its successors all employed 6-, 8- and 12-cylinder engines.

The 906

The 906 was also known as the Carrera Six, and was Porsche’s last road-legal racing car. On road-based events, such as the Tour de France Auto and Sicilian Targa Florio, it fulfilled both roles. Works drivers Willy Mairesse and Herbert Müller won the 1966 Targa Florio outright in a 906.

The 906 – Carrera Six – was the last racing car that Porsche made that could be legally driven on the public road.

The 906, with its mid-mounted 2.0-litre flat-6 engine, was built on an elaborate multi-tubular spaceframe chassis, reverting to earlier practice. Like the 904, it was clad in a relatively crudely-made glassfibre body, although unlike the 904, the 906’s broader, flatter shape stemmed from wind-tunnel tests. For 1966, Porsche was looking to participate in the new Group 4 category for competition sports cars whilst continuing to produce the prototypes that honed the breed, which meant producing a minimum of 50 identical machines, so again, the 906 served both purposes. In total, 65 examples were made.

The 907

Based on its contemporary 910’s chassis, the 907 featured more aerodynamic bodywork, characterised by its long, rounded windscreen and perspex cover like the 906’s over the 2.2-litre flat-8 engine. Launched at the 1967 Daytona 24-Hours, the three longtail 907s crossed the finishing line together (in a dramatically staged finish), taking the first three places. Probably 21 cars were made. As much as any other, this result established that Porsche now had the measure of the rival titans Ford and Ferrari (see 2019 film Ford v Ferrari).

Virtually siblings under the skin, the 907 KH of 1967 (left) and 908 LH of 1968 (with its complex rear aerofoils) were fundamental in raising Porsche to a higher level in the World Sportscar Championship stakes.

A trio of 907 LHs cross the finish line together in a staged dead heat at the end of the 1968 Daytona 24-Hours. The actual winners were Vic Elford and Jochen Neerpasch in number 54.

The 908

For 1968, the FIA introduced rule changes for Group 6 prototype-sports cars, limiting engine displacement to 3.0-litres, and Porsche designed the 908 accordingly. The new 908’s air-cooled 3.0-litre flat-8 produced 350bhp at 8,400rpm. The 908 was originally configured as a coupé, almost identical to the 907, and now with the driver’s seat located on the right-hand side, since most race circuits ran clockwise, and having the driver’s weight on the right aided cornering stability. From 1969 on, the 908 was mainly raced as the 908/2, a lighter, open-top Spyder, known as a ‘Flounder’ due to its flat-fish form. The much more compact 908/3 was introduced in 1970 to complement the heavier Porsche 917 on twisty tracks that favoured nimble cars, like the Targa Florio and the Nürburgring. Probably 31 cars were made.

Two vastly different incarnations of the 908 posed at Classics at the Castle: the 1969 long-tail ‘Lang Heck’in the foreground and the compact 1971 Martini Team 908/3 beyond.

The 909

Known as the Bergspyder, the Type 909 consisted of just two pared-to-the-bone lightweight Spyders, used exclusively in two rounds of the 1968 European Hill-Climb Championship. They were underdeveloped, but paved the way for the 908/3.

One of the disciplines that Porsche excelled in was mountain climbing, and lightweight versions were built to contest the European Hillclimb Championship during the 1960s, including the one-off 909 Bergspyder.

The 910

Launched in 1967, Porsche made 22 units of the 910 coupé, powered by the 220bhp 2.0-litre (1991cc) flat-6, and thirteen cars were fitted with the 260bhp flat-8 in 2195cc and 1981cc format, of which seven were coupés and six were spyders. The 910 used the same complex steel tube-frame chassis as the 906, similarly clad in glass-fibre bodywork bonded to the triangulated tubes at strategic points. The principal differences included the pioneering (for Porsche) centre-lock 13in wheels, shod with correspondingly lower profile tyres, allowing a much sleeker, co-ordinated body shape. For the 1967 Targa Florio, six 910s were dispatched – three flat-6s and three flat-8s, all fuel injected – and they took the first three places.

The 910 #017 of Vic Elford and Lucien Bianchi traverses Brands Hatch’s South Bank Bend during the 1967 BOAC 500. It retired with faulty valve gear.

The 917

Porsche won the 1969 World Sportscar Championship – the International Championship for Makes – with outright victories in the 1,000km races at Brands Hatch, Monza, Spa and the Nürburgring, as well as the Targa Florio. But they had yet to win the coveted Le Mans 24-Hours trophy outright; the car intended to achieve this was the 917.

The 917 was constructed to FIA Group 4 regulations, powered by a flat-12-cylinder engine that was progressively enlarged from 4.5-litres to 5.0-litres. At first, it proved unwieldy on track, but swiftly went on to dominate sports car racing in 1970 and 1971. Drivers Richard Attwood and Hans Herrmann drove their 917 to victory in the 1970 Le Mans 24-Hours, breaking the duck as far as Porsche was concerned in that particular iconic event.

Photographed in the underground car park at the Porsche Museum at Zuffenhausen, this 917 KH is liveried as chassis #023, the car that won the 1970 Le Mans 24-Hours.

Donington Circuit’s Kraner Curves section provides a thrilling prospect for the author at the wheel of the 917, as recounted later in the book.

Peter Vögele drives 917 #025 at Classic Le Mans 2018. The car was originally sold to Dominique Martin’s Zitro Racing Team in 1970, and ran in the 1971 Buenos Aires 1,000 Kms placing 10th, the Monza 1,000Kms finishing 9th, and also at Spa and the 1971 Le Mans, co-driven by Gérard Pillon.

FIA GT and European Le Mans Series Champion Marc Lieb drives the 1,000bhp twin-turbo 917/30 on Weissach’s Can-Am circuit, formerly raced by Herbert Müller in the European Interserie Championship in 1974.

RULING THE ROOST

When the FIA rules changed for 1972, the 917 and its contemporary Ferrari 512S were sidelined in favour of 3.0-litre prototypes; Porsche had been running 3.0-litre 908 prototypes since 1968, but the new breed would be powered by Formula 1 engines, and Porsche declined to get involved. So, while Ferrari fielded the 312P, Porsche took a breather to develop turbocharged racing versions of the 911, Gijs van Lennep and Herbert Müller winning Le Mans in 1974 with the 911 Carrera RSR Turbo. However, Porsche had already developed the open-top 917 PA Spyder for Can-Am racing in North America, culminating in the mighty twin-turbo 917/30 Spyder that won the Can-Am title in 1972 and 1973. It was so crushingly invincible that all the opposition fell away, and the category was abandoned. The 917 Spyder also won the Can-Am equivalent European-based Interserie championship every year from 1969 to 1975. Sixty-five cars were built.

A brief historical perspective. Previous Porsche racing cars from the early 1960s were the RS60 and RS61, with Porsche on a steady roll since it began racing with the 550 Spyder in 1953. Equally significantly, the firm’s roots go way back to Professor Ferdinand Porsche’s successful racing car designs for Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union in the 1920s and 1930s, prior to him setting up his own company in 1948 with his son Dr Ferry Porsche. It was the latter who oversaw the rise of the marque to successful international status during the 1950s and 1960s, with talented lieutenants including Huschke von Hanstein, Hans Mezger, Helmuth Bott, Peter Falk and (successor) Ferdinand Piëch masterminding the engineering that steered Porsche to the top of the charts in world-class endurance racing. It is quite a fantastic saga of racing car evolution in a particularly dangerous yet swash-buckling era, with Porsche gaining supremacy over deadly rivals Ferrari and Ford.

From regular and reliable class-winners in the early- to mid-1960s, Porsche evolved into outright winners in events like the Sicilian Targa Florio road race, an arduous 80-mile lap of largely mountain backroads that suited the size, handling and power-to-weight ratio of Porsche race cars. As we will see in more detail later on, the Targa Florio became something of a Porsche speciality, with eleven victories spread from 1959, 1960, 1963, 1964, and every year thereafter from 1966 to 1970, as well as the final race in 1973 for good measure. Porsche also logged nine 2nd places and twelve 3rds, slightly better than runners-up Alfa Romeo, and much better than Ferrari. In this respect, the Targa Florio is a better yardstick of Porsche’s excellence in the sporting arena than the much vaunted Le Mans 24-Hours, in which it was successful in respect of class wins during the 1950s and 1960s, but did not win outright until 1970.

Gijs van Lennep and Jacky Ickx shared the winning Type 936 #002 at the 1976 Le Mans 24-Hours, the third such victory for the Belgian and the second for the Dutchman.

Porsche won the Daytona 24-Hours in 1968 with the 907, and the Targa Florio in 1968 with the 908, at last conquering Le Mans outright in 1970 with the 917. These are the bare bones, steps on the ladder: over the course of six chapters, the book broadly charts the introduction, evolution and race career of each specific model.

The 917 became defunct when the rules were changed by the FIA for 1972, after which Porsche adapted its road-going 911 2.7RS into the 911 Carrera RSR Turbo, 934 and 935, which also became outright Le Mans winners. That makes the period between 1964 and 1971 very much a standalone era, witnessing the rise of Porsche from a regular and reliable class winner to the out-and-out victor. Porsche’s success on the racetrack was, thereafter, a given. By 1976, the 917’s spiritual successor, the 936, was the Le Mans and World Championship winner, followed by the virtually unbeatable 956 and 962 in the Group C series of the 1980s.

CHAPTER 1

THE PORSCHE 904 CARRERA GTS 1963–66

The 904/6 of Ralf Kelleners and Afschin Fatemi comes perilously close to the wall at La Source hairpin during the 2016 Spa Six Hours.

P orsche set out to design a completely new car in 1963 to maintain their stronghold in the under 2.0-litre GT racing class. The 904’s inception was partly in response to the introduction of the Alfa Romeo GTZ (Tubolare Zagato) and Abarth’s 1600 OT (Omologata Turismo), designed specifically to contest the FIA GT class. For homologation purposes, they needed to build at least 100 units of the new car in twelve months, and, as far as Porsche was concerned, the new model would have to be a road-going model because, in those days, they would be unlikely to sell 100 full-on race cars. As a road-going model, it still conformed to Group 3 Appendix J rules. The firm’s Formula 1 programme was sacrificed to free up resources to design and develop the 904, on the assumption that the development costs of the GT racer would be recouped by sales. Porsche’s engineers started with a clean sheet for the 904 because the tubular spaceframe construction employed in the construction of the Type 718 and RS60/61 Spyders would be too expensive and time-consuming in the creation of what was going to be a production car. The 718’s mid-engined layout was carried over so that the Fuhrmann four-cam ‘Carrera’ flat-4 unit was mounted between the cockpit and rear axle on a steel ladder-frame chassis, and clad with fibreglass (GRP) body panels. Ferry ‘Butzi’ Porsche, grandson of founder Prof Ferdinand Porsche and designer of the 911, was responsible for the styling of the plastic body. He included some of the styling cues and the windscreen of the 718 in the design, and the fabrication of the body panels was outsourced to aircraft manufacturer Heinkel, who moulded two bodies a day, while Porsche managed a single chassis a day. Heinkel’s methodology involved spraying chopped fibreglass into moulds rather than the laying-up by hand method employed by manufacturers such as Lotus (pre-VARI) and TVR at the time. The 904’s upper and lower bodyshell panels were bonded and bolted onto the ladder chassis, a configuration that proved to be more rigid than the previous spaceframe chassis.

The 1967cc 904 GTS flat-4 is cradled amidships, in this case with an oil tank to the right and petrol tank at the rear.

Five 904 GTSs under construction in the Porsche Zuffenhausen factory – testing took place on the newly completed Weissach track – featuring ladder chassis, engine cradles and flat-4 motor, with fibreglass bodies bonded and bolted to the chassis.

The original plan was to install the brand new 2.0-litre flat-6 engine, designed for the forthcoming 901/911, but it was not ready when Porsche needed to present the car for homologation, so the 1966cc Type 587/3 180bhp quad-cam 356 Carrera 2 engine was used instead, allied to the road car’s new five-speed gearbox. The suspension consisted of coil springs and dampers rather than trailing arm front and swing-axle rear suspension, with unequal-length A-arms at the front. Brakes were 275mm (10.8in) discs at the front and 285mm (11.2in) at the rear.

Front brake disc, caliper, wishbone and damper of a 904/6.

The Stanley Gold 904/6 demonstrates the Kamm Tail aspect of its styling, which contributed to its aerodynamic shape.

Three 904 prototypes were constructed and tested during the autumn of 1963, and the car was unveiled in late November. Within the factory, it was referred to by its ‘904’ type number, but at launch, it was marketed as the ‘Carrera GTS’. Their confidence was not misplaced: a fortnight after introduction, only 20 of the 90 units slated for public consumption were unsold. Production started soon afterwards in the new 901/11 plant, and by April 1964 the 904 was homologated as a Grand Turismo racing car. January 1964’s Motor Sport magazine published a front three-quarter shot of the 904, with this extended caption:

The Porsche Type 904 GT coupe, which is for sale to racing customers, has a fibre-glass body bonded to a steel box-sectioned chassis. It has a ‘Manx-tail’ end to the body, and the rear window is vertical, sunk into the smooth contours of the sides. Grilles behind the doors take in air for the Weber carburettors and for the cooling fan. Disc brakes and bolt-on wheels are used, while the slot in the nose takes in air for the oil cooler.

Porsche’s 904 project was also a radical departure from the series of Carreras developed in the past, the engine in the new car being in front of the rear axle, as on a Porsche Spyder, instead of behind the axle. The Porsche 904 bore no resemblance to any previous production models, and they probably built 114 altogether. Autosport revealed the specification of the new 904, commenting on the innovative trend for placing the powertrain of competition Grand Touring cars amidships:

Ferrari has adapted the much better mid-engine position, which is in front of the rear axle but behind the driving compartment, which is standard Grand Prix layout. And while Porsche did this with their experimental GT coupé using the 8-cylinder engine, the production GT cars were full rear-engine layout. The new Porsche is designated the Type 904, not to be confused with the Type 901, which is the touring 6-cylinder that appeared recently at all the motor shows…

(and, of course, became known as the 911).

The new 904 was a complete break from Porsche tradition in its construction, with a chassis frame comprised of two deep-section box members, suitably cross-braced, whereas previous Porsche coupés – the 356s – were of monocoque construction, made from thin sheet steel or sheet aluminium. The 904 suspension consists of double wishbone and coil-spring front suspension, rack and pinion steering, and double wishbone and coil-spring rear suspension, all of which are descended from the F1 and F2 Grand Prix 787 and 718 Porsche 8-cylinder cars. The air-cooled 2.0-litre Carrera 4-cylinder engine is mounted ahead of the rear axle, with transmission via a 5-speed Porsche gearbox, and the drive is taken to the independently-sprung rear wheels through one-piece driveshafts, having inboard universal joints that not only swivel in all planes, but also extend in and out on short links, giving friction-free movement to the rear end. These new universal joints achieved by mechanical means the same effect as Lotus arrived at with the rubber-ring ‘doughnut’ universal joints used on their 1960s racing cars.

The 904 coupé body is made of fibreglass, in two longitudinal halves – top and bottom – and bonded and bolted to the chassis frame, the whole tail hingeing upwards to give access to the engine and gearbox. The 4-cylinder engine has a 92 x 74 mm bore and stroke, giving 1966cc, and develops 180bhp at 7,000rpm, using Weber carburettors and a 9.8:1 compression ratio. Porsche insisted, correctly as it turned out, that it was not an ‘airport racer’, but an all-around GT car that could run in the Targa Florio and on smooth circuits or in rallies of the Tour de France type.

Six-cylinder engine and transmission of the 904/6 are cradled off the rear of the ladder chassis, which also provide pick-up points for the rear suspension.

THE 904 IN RACING

The race record took off at the 1964 Sebring 12-Hours, where drivers Lake Underwood and Briggs Cunningham’s 904 finished 9th overall and 1st in the prototype class. It was the beginning of a highly successful racing career, including overall victory in the Targa Florio for unfancied veterans Colin Davis and Antonio Pucci, and many class victories in the WSC 1,000km endurance races and the Le Mans 24-Hours, while rally successes included Eugen Böhringer and Rolf Wütherich (who was the ill-fated James Dean’s 550 Spyder co-driver) finishing 2nd in the snow-bound 1965 Rallye Monte Carlo.

During 1964, Porsche continued to develop the 904 and provide customers with uprated components to keep the cars on the pace. Two factory race cars were fitted with a 2.0-litre version of the F1 718’s flat-8 engine, and later in 1964, the flat-6 appeared, although these unhomologated cars ran as prototypes.

Taking the Targa Florio as a good benchmark for judging a car’s overall prowess – not to mention that of its drivers –Porsche’s victory in 1964 carries as much weight as Ferrari’s Le Mans win the same year. Horses for courses at this point in time. As Motor Sport magazine’s Denis Jenkinson reported in its June 1964 edition, ‘a production competition GT car had won, and undoubtedly vindicated Porsche’s policy of development through racing’.

Historically, Porsche won their class virtually every year since they first ran at Le Mans – La Sarthe – in 1951, and the 904 GTS was no exception, coming 4th and 5th overall in 1965, and winning the imponderable Index of Performance and Index of Thermal Efficiency categories. We are shortly going to take a close look at the car that was the Targa Florio victor, one of the original works’ 904 GTSs making its European debut at the Sicilian enduro on 26 April 1964. Driven by veterans Colin Davis (an ex-pat British racer who lived in Rapallo) and Baron Antonio Pucci from Palermo, for five laps each of the 72km Piccolo Madonie circuit, chassis 904-006 (race number 86) outlasted both its prototype siblings around the sinuous mountain course, not to mention the host of Alfas, works Ferraris, debutant GT40 and sundry Cobras. After Davis set the fastest lap at 41m 10.5s, Pucci put the car into the lead on its 7th lap, and they were followed home by a second works’ 904 GTS driven by Herbert Linge and Gianni Balzarini. As Motor Sport’s Denis Jenkinson said in his report of June 1964:

In the Porsche pits there was an air of satisfaction, for though the works prototypes had broken down, they had a production GT car in the lead with an older model in second place and another 904 model in fourth place, while the eight-cyl-inder car of Barth and Maglioli had been repaired and was running again, but too far behind to hope to get anywhere.

This was regarded as an outstanding success, since the 904 was essentially the company’s first customer racing car, and (apart from Sebring) they had proved it was a winner from the outset.

Also on the Porsche driver roster were a couple of Formula 1 stars: Jo Bonnier and 1962 F1 World Champion Graham Hill. This compelling duo had raced for Porsche since 1960 in Hill’s case, and 1961 in Bonnier’s. But, having practised as assiduously as only Hill could, he did not get a go in the 1964 Targa, Bonnier having retired the car on the second lap.

Midway through the 1964 season, Motor Sport’s Jenkinson took stock:

At one time a GT car was a practical and usable road car that could be raced, but development and the rules has caused the appearance of the Porsche 904 and the Ferrari 250 LM, which are splendid racing cars but not everyday GT cars, although there are people who use a 904 as a road car. It has also developed very fast and powerful racing coupés that are getting into the hands of inexperienced drivers, as witness the number of crashed 904 Porsches this season, and had there been a hundred Ferrari LM models available there would have been a lot more crashes – not because there is anything wrong with these cars, far from it, but they are very fast racing machines and there are not more than 20 or 30 drivers in Europe capable of handling them to their limit.

And he would know what he was talking about, having navigated Stirling Moss to victory on the 1955 Mille Miglia.

At Le Mans 1964, the headliners were the Ferrari 3.3-litre 275P prototypes – the mid-engined cars appearing for the first time – and 250 GTOs, vying with the AC Cobras for outright supremacy. The prototype class up to 2000cc was a predictable victory for the lone 8-cyl-inder Porsche of Jo Bonnier and Richie Ginther. After the throttle-sticking troubles had been sorted out and a moment of alarm when Bonnier thought the rear suspension was falling off, the car ran well, albeit two laps behind the overall winner. A further four 904 GTSs occupied the top ten positions.

Herbert Linge drove the 1981cc flat-8 powered 904/8 at the Norisring street circuit on 5 July 1964.

Antonio Pucci and Colin Davis on their way to winning the 1965 Targa Florio. The photo gives an idea of the arduous nature of the circuit’s terrain.

The 904 GTS was an effective rally car, pictured here at the 7th International Porsche Ski-Treffen Winter Rally at Zürs-Arlberg, Austria, in 1964.

The 904 GTS of Antonio Pucci/Colin Davis won the 1965 Targa Florio, with Gianni Balzarini/Herbert Linge 2nd in another 904 GTS.

F1 stars Graham Hill and Jo Bonnier brought this 904/8 home in 4th place in the 1965 Targa Florio. The 904/8 Känguru is just visible behind it.

Dutch Porsche concessionaire Ben Pon steps between a quartet of works’ 904 GTSs in the Nürburgring paddock during the 1965 1,000Kms meeting. Pon and Koch finished 25th.

THE 904 GTS SPEC

Introduced in December 1963, the 904 GTS consisted of a pressed steel frame made up of rectangular section longitudinal beams and cross-bracings. A new departure from aluminium panels was the lightweight, curvaceous fibreglass body made for Porsche by Heinkel: very pretty, even though the bottom half did not quite line up with the top half, which left a peculiar lip along the length of the hull. The 1967cc 587 Carrera flat-4 engine developed 180bhp @ 7,000rpm and was mounted amidships ahead of the axle, while a new gearbox was located behind the axle, allied to a single-plate clutch and ZF limited slip diff. The suspension consisted of unequal-length wishbones at the front with wishbones and twin forward-facing radius rods and coil springs at the rear. Larger ducts for cooling the bigger rear brakes mark out the 904/6, and it was superseded in 1966 by the 906, or Carrera 6. Bluntly, the 1964 launch of the 911, whose completely new 6-cylinder engine and modified MacPherson Strut front suspension represented a clean break with Porsche tradition, rendered the 904 obsolete. By 1966, it had been swept away by Porsche cousin Ferdinand Piëch and his Carrera 6. Meanwhile, the 904 Carrera GTS enjoys a unique place in the manufacturer’s history as the last competition car to be fitted with the four-cam, 4-cylinder Carrera engine.

The fuel tank and on-board fire system are located in the nose of the 904/6.

The 904/6’s rear suspension involves reversed upper wishbones, upper and lower longitudinal radius arms, coil-over dampers, and an anti-roll bar.

Interestingly, there was much debate about top speeds achieved by the fastest Ferrari and Lola-Ford prototypes: a radar beam positioned on the Mulsanne Straight – long before chicanes were installed – indicated that Richie Ginther’s Lola had hit 340km/h – 211mph – by virtue of slipstreaming three works Ferraris.

The 904 GTS entered by August Veuillet and driven by Robert Buchet and Guy Ligier came 7th overall at Le Mans 1964.

TYPE 904 CARRERA GTS MAJOR SUCCESSES

1964

1st, Targa Florio

3rd, Nürburgring 1,000kms

7th, 8th, 10th, 11th, 12th, Le Mans 24-Hours

1st, Reims 12-Hours

1st, Tulip Rally

1st, Alpine Rally

1st, European Hillclimb Championship, GT & Sports classes 1965

1st, Rossfeld Hillclimb

1st, Gaisberg Hillclimb

1st, European Hillclimb Championship, GT class

2nd, Monte Carlo Rally

2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, Targa Florio

4th, 5th, Le Mans 24-Hours

CLIMB EVERY MOUNTAIN

Meanwhile, Porsche was invincible in hillclimbing – mountain-climbing, or Berg-Rennen, as it is known in Europe. At Rossfeld – close to Hitler’s Berchtesgaden eyrie –Edgar Barth won Round 1 of the European championship in an 8-cylinder Elva-Porsche, with Herbert Müller second in an 8-cylinder 904. Heini Walter set a new 2.0-litre GT record in a 904. I have driven this course in a 991 Turbo, and it is, to my mind, more thrilling than lapping a racetrack, partly because of the topography and fathom-less drop-offs, and the demands of negotiating numerous hairpin corners.

Here is Autosport’s take on the uphill series:

At the time of going to press, three further events have taken place in the European Hillclimb championship, these being Mont Ventoux in France on June 14th, Gaisberg, Austria, on June 28th, and Trento-Bondone in Italy on July 12th, making with the Rossfeld meeting a total of four rounds out of this series of seven.

Mont Ventoux was the longest event in the championship curriculum, measuring 22 kilometres or 13 miles, and incorporated the most gruelling road surfaces imaginable. Current champion Edgar Barth, who won the first event with a flat-8-engined 2.0-litre Elva Porsche, switched to last year’s championship-winning flat-8 Porsche prototype, and he had little difficulty in winning the championship class from Anton Fischaber’s Lotus-BMW. Gaisberg, like Rossfeld, required competitors to score on an aggregate of two runs. Barth once more set the pace and scored his hat-trick, and Müller, with the hurriedly prepared Elva-Porsche, was placed second. The meeting was full of incidents, most of which could be blamed on poor crowd control.

When I drove the Gaisberg climb in 2019 in a Porsche 718 Cayman with Antony Fraser, there were no such problems, though the hilltop restaurant was very popular with hikers as well as car and bike fans, and parking at the summit was difficult. On the other hand, we had the Zistelalm Hotel, mid-way up the climb, virtually to ourselves. Back then, Barth’s best time of 4m 11.54s for the 8.5km hill course constituted a new outright record. The sinuous 17.5-km Trento-Bondone climb in northern Italy was the scene of Barth’s fourth consecutive win, which clinched for him the 1964 European title, with three further qualifying events. His time of 12m 17.8s bettered his old record by 0.08 of a second.

Two further events, Cesena-Sestrière on 26 July and Schauinsland-Freiburg on 9th August, came next. Edgar Barth, who had already assured himself of the title for the second successive year by winning Trento-Bondone, continued to dominate the championship with his works-entered 2.0-litre 904 prototype, and won at Cesana in a new record time of 5m 33.1s. Second place went once more to the young Swiss driver Herbert Müller in the Scuderia Filipinetti 2.0-litre flat-8 Elva-Porsche, over five seconds behind the winner. At the penultimate round, Freiburg-Schauinsland, Barth kept up the pressure to notch up his sixth successive championship win, ascending in a new record time of 6m 40.66s for the 11.2km course. This is another key European hillclimb I have driven a few times, courtesy of local Porsche spares specialists FVD Brombacher – father and daughter Willy and Franziska – variously in a 997 GT3 4.0, a 992 GTS and a 996 GT2. We never reached the summit in one go, always irresistibly tempted to stop at the halfway-house Sternwald restaurant. Record-breaking was never the goal.

Rolf Stommelen was 3rd of three 904 GTSs on the wet Gaisberg Hillclimb on 19 September 1965, with Michel Weber 1st and Sepp Greger 2nd. The author, and photographer Antony Fraser, fondly remember staying at the Zistelalm Hotel when reprising the route in 2019 aboard a 718 Cayman.

Michel Weber’s 904 GTS recorded 4th fastest time up the Trento Bondone hillclimb on 10 July 1966, behind Mitter’s 906, Herrmann’s 910 and Greger’s 906.

The 904 of Michel Weber being fettled in readiness for the 1966 Schauinsland-Freiburg Hillclimb, in which he came 4th. Mitter’s 910 coupé was the winner.

THE 1964 SEASON

For the Reims 12-Hours race on 5 July 1964, the Porsche factory entered a lone 8-cylinder version of the 904 GTS coupé for Edgar Barth and Colin Davis and a full series production 904 for Gerhard Koch and Gerhard Mitter, and there were eight further 904 models in the hands of private owners. The event had last been held in 1958, when it had been run for GT cars. Now, prototypes augmented the entry list, effectively a half-distance Le Mans. The main concern was the after-dark start, with the traditional Le Mans-style sprint across the track for drivers to leap aboard their cars. The 904/8s were quickest away, and very quickly, a new average lap speed was posted of 203km/h – 126mph – in the dark, with two virtual hairpin bends to cope with on the road circuit. I expect most of us have paused there for the obligatory selfie beside the renovated pits, and to marvel at the speeds potentially attainable on those long, straight public roads.

A pit stop for JT’s 986S on the former Reims Grand Prix circuit, once home to the International 12-Hour endurance race, whilst covering the Rallye Monte-Carlo Historique with photographer Alex Denham.

Herbert Linge’s 904/8 exhibits a bit of lean as it rounds a hairpin on the Norisring street circuit, Nuremberg, 5 July 1964.

Anyway, behind the Ferrari LMs, Lola-Fords and AC Cobras, the 904s began moving into the higher places as faster cars retired. In the final outcome, Porsche placed 5th, 6th, 7th, and 10th, and we note the name van Lennep at 15th, sharing a 904 with van Zalinge entered by Racing Team Holland.

The wonderfully expansive Tour de France Automobile was, at the time, a round of the FIA World Sportscar Championship. The Tour Auto was organised annually by the Automobile Club of Nice, with the participation of the French Shell Oil company and many other firms, including Dunlop Tyres. The idea of the event was very simple: a few French racing circuits were selected, together with an equal number of hill climbs, and then ten days were taken up driving around between them, with every other night being spent in a hotel at one of the selected towns. This may sound like a very relaxing way to go rallying, but anyone who has competed in this event will be quick to disabuse you of that fallacy. The actual amount of rest that the drivers and navigators got was minimal, and the event was no less of a strain on the competing cars, demonstrated by the high proportion of retirements.

Between 1960 and 1962, the number of starters remained constant at 116, while the number of finishers fell from 48 to 46, and in 1963, only 31 survived out of 122 starters. This was serious stuff, making the modern pastiche – the Tour Auto Optic for classic cars run by Peter Auto, who also run Classic Le Mans among other historic events –look something of a jolly. An enjoyable one, nevertheless. With certain reservations: I lost my driving licence covering it one year in a press Boxster 987 S, caught doing 160mph (258km/h) on a stretch of brand new autoroute in the Dordogne while leapfrogging a stage or two for the benefit of my colleague Antony Fraser (who needed to be ahead of the rally retinue in order to take photographs as the cars swept by). Having brusquely confiscated my licence at the next péage, the arresting officer demanded to see Antony’s so he could lawfully take the Porsche’s wheel. He was unable to produce it, the document being at the time in the care of the Yorkshire Constabulary. Fortuitously, the discovery of a letter from Porsche in the glove box identifying us as legitimate custodians of the vehicle enabled us to proceed to the Albi racetrack and beyond, to Clermont-Ferrand’s Charade circuit.

Like the Alpine A110 behind it, the 904 GTS is a great handling car on a tarmac stage event like the French Tour Auto, seen here at the Souillac start in 2008.

Stanley Gold’s 904/6 going neck-and-neck with an Alfa Romeo Giulia TZ2 during the Plateau 4 race at the 2012 Le Mans Classic: both models are well matched in performance and handling.

Four decades earlier, in the GT category, the Porsche 904 GTSs were up against Alfa Romeo GTZs and sundry MGBs, Spitfires, Renault Alpines and Renée-Bonnet Djets. The works Porsche 904s of Robert Bouchet/Herbert Linge and Gunther Klass/Rolf Wütherich were never seriously challenged, and they took the win in the GT category, with 904 GTSs occupying 3rd through to 6th places in the leading classifications.

The 1964 season closed with the Linas-Montlhéry 1,000kms on the spectacular partly-banked circuit just south of Paris. It marked the first appearance of a Porsche 904/6 GTS, being a 904 GTS with a 6-cylinder engine replacing the original 4-cylinder Carrera engine. Outwardly, the new car was basically a production 904 fibreglass coupé, and the flat-6 engine was of the type being fitted to the new production touring Porsche, still known as the 901. This explains partly why the 904 GTS was originally designed with so much room in the engine compartment, because when you hinge up the tail of a 904, the 4-cylinder Carrera engine looks a bit lost in a fore-and-aft direction. The air-cooled flat-6 engine fits in very nicely.

Overhead view of the 904 GTS with engine cover partially hinged backwards, revealing the 1967cc flat-4 engine.

STANLEY GOLD’S 904 #006

The Gold/Junne 904/6 in the Le Mans pitlane during the 2012 Classic event.

Among the marvellous machinery at Classic Le Mans in 2010 was a former factory 904 GTS race car, which just happened to have that 1964 Targa Florio win to its credit, and owner Stanley Gold gave chapter and verse on its life and times. The event was a veritable Porsche fest, with fans and factory thronging to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the marque’s first win at La Sarthe.