Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

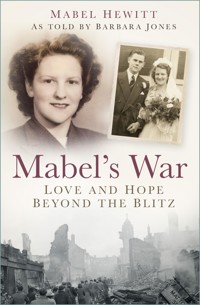

With devastating clarity and gentle humour, Mabel Hewitt takes us through her extraordinary life, from her childhood in the shadow of the First World War right up to the present day. Born in the tumultuous thirties, when the threat of the poorhouse hung over working families, she was just 10 years old when war clouds began to gather across Europe. She remembers air-raid sirens, taking shelter underground with her mother and sisters, and the utterly terrifying Coventry Blitz, when almost two-thirds of the city was destroyed or damaged. And yet, despite everything, her spirit shines through. Mabel's War is a poignant account of love and hope during some of the country's darkest days.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 206

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Young love, arm-in-arm along the prom at Whitley Bay, 1947.

Praise for Mabel’s War

Mabel’s War is not just a lively, fascinating memoir of everyday reality in one of Britain’s key wartime industrial cities – and most notorious of the Luftwaffe’s targets – but a timely and chillingly stark reminder of the hardships and miseries of working-class life before the creation of the modern welfare state.

Frederick Taylorwar historian

It’s a great read – and very moving. I didn’t expect to be reading the book from cover to cover in such a short time but I was unable to put it down for more than a few minutes. Many thanks for a fascinating book.

Rev. William HowardSecretary of The Friends of Coventry Cathedral

I haven’t read anything so viscerally direct about wartime conditions. The extreme hardships bring out Mabel’s feisty nature. I find the detail fascinating and I learned some things I didn’t really know. The simple and direct writing style makes it seem as though it’s all just happened and it’s told with such clarity that its impact is immediate.

Herry Lawfordstep-grandson of Coventry industrialist and philanthropist Sir Alfred Herbert

Cover illustrations: Mabel in her St John Ambulance Brigade uniform; Mabel and John on their wedding day; bomb damage in Coventry (Mirrorpix/Alamy)

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Mabel Hewitt, 2023

The right of Mabel Hewitt to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 300 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Author’s Notes by Barbara Jones

1 Born in Troubled Times

2 The Make-Do-And-Mend Years

3 Evacuation: A Painful Ordeal

4 Storm Clouds Gathering

5 My City, Hitler’s Target

6 The Night Without End

7 Finding John

8 Beyond the Blitz

9 A Good Life, Well Lived

Epilogue: My Proud Legacy

Author’s Notes

by Barbara Jones

All wars devastate the lives of ordinary people. Death and glory linger on the battlefields while many millions at home suffer the pain of fear, anxiety and dread. As a war reporter, I have witnessed a great deal of anguish in the aftermath of conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, always conscious of how the Second World War blighted an entire generation in our own country where bombs rained down on defenceless towns and cities.

Few people are still alive to recall those times and 93-year-old Mabel Hewitt stands tall among them as a spirited eloquent eyewitness to one of the worst-ever attacks on civilians and their homes.

She endeared herself to millions when she appeared on BBC TV in a commemorative programme and talked movingly of her night in a bomb shelter during the terrible Coventry Blitz in November 1940. A reviewer for The Times newspaper called her ‘formidably likeable’. Mabel’s family asked me to work with her on producing her life story. It was inspiring, enriching, a revelation.

In a rare lifetime that spans the struggle of 1930s Britain, the onset of a cruel war and childhood memories of her city reduced to rubble in the Blitz, Mabel has a treasure-trove of wisdom she is ready to share. Her earliest memories are of a crowded house in Coventry’s city suburbs with her six siblings, parents, grandmother and an uncle. Her brutally strict father ruled the household; her mother was completely cowed. Mabel remembers the fear, and the pervasive cold.

She knew even then that life could and should be better than this. Nothing would stop her seeking that out. She began to develop a determined streak that saw her survive poverty, deprivation and worse. Mabel lived through terrible times. She believes that some of today’s children, in their own way, are also living through terrible times. She wants them to know that life can be better. She is a strong, determined woman who wants to inspire others through her personal example. That is why she is telling this story.

In the 1930s, there was no welfare state, no child benefit or help for the poor. The threat of the workhouse was ever present. Mabel remembers children coming to her school with no shoes. It was a life of make-do-and-mend. She was 10 when Britain found itself at war with Germany. Mabel was among the bewildered children sent to strangers’ homes in the countryside to save them from the anticipated bombing onslaught.

In the chaos of the government’s rushed evacuation programme, she was separated from her siblings and billeted with a family whose home life was actually harder than her own. There was no running water, just a standpipe in the yard serving several families. Her foster parents had a newborn baby who cried day and night. There was no heating, no electricity and a ‘thunderbox’ toilet in an outhouse. Mabel shivered miserably through the nights on an old camp bed on the landing. But worse was to come. The man of the house invited her into his bed ‘to get warm’ and terrified her with his advances.

She packed her cardboard suitcase and left. Mabel had found the inner strength which would see her through many tribulations as wartime bombings escalated and her city became a crucial target.

The notorious attack of 14 November 1940, when Coventry was set ablaze in Britain’s longest night of German bombing raids, is etched into her memory. Mabel was hiding in the family’s Anderson shelter from where she witnessed the sights and sounds of a bombardment which horrified the world. The city’s medieval cathedral, fire-bombed into rubble and ashes, was at the heart of an extraordinary campaign of reconciliation and forgiveness just a few days later.

Mabel was beginning to learn about the healing power of forgiveness alongside the need to survive evil and overcome it. She was to learn assertiveness in the workplace when she left school at 14 and was assigned a lowly job in a local munitions factory. Determination won her a different career path. She wants today’s youth to know they can be assertive too.

The turning point in her young life of hardship and sorrows was when she found the man who would be her husband and her rock. Love and hope, Mabel believes, are crucial. She found herself in a warm, loving family with John Hewitt and his kind parents. Together they created their own close and happy family. She lost John too soon; he died at 56. It was family and friends, and Mabel’s determined cheerfulness and optimism, which saw her through.

Later she suffered a devastating illness of her own, and spent six years in treatment for bladder cancer. At 88, she received the all-clear.

Today, at 93, Mabel is an inspiration to those around her. Loved by three generations of her own family, she has a unique place in her local community with loyal friends and neighbours. Content with modest pleasures – a pretty garden, a comfortable home adapted to her mobility needs, reading and listening to music – she looks back on a life well lived and struggles overcome.

Mabel takes a keen interest in today’s young people and their struggles. She wants them to know they can also find inner strength and achieve a better life. Mabel’s Enterprise, a Community Interest Company (CIC) set up by her grandson Matthew in her name, aims to inspire young people. It is her way of reaching out to them.

Barbara Jones,Foreign Correspondent

1

Born in Troubled Times

Looking back, I can see that the sad shadows of war darkened the whole of my young life. The legacy of horrendous suffering and sacrifice in the First World War was there from the day I was born. My father, strong and wiry, was a cold-hearted frightening presence to me as a small child and that fear pervaded our household. His whip-handled cane stood in the corner, ready to be snatched up and used to threaten us for any minor transgression. His old widowed mother, my Granny, lived with us in the city suburb of Holbrooks, in Coventry, and shared a bedroom with me and my sisters. We thought of her as a witch, always dressed in black, with a temper to match.

Today I understand that my father Ben Goodwin, serving as a farrier for four long years in the horse artillery at Ypres, was undoubtedly scarred by the sights and sounds of that muddy wartime hell. They say that 368,000 horses served alongside soldiers on the Western Front, holding back the German army as it tried to fight its way through to reach the ports of Dunkirk and Calais. My father cared for horses that pulled the supply wagons carrying ammunition to the front line. Sometimes they returned carrying the wounded and dead. Always in the wintry mud. Heavy draught horses pulled artillery guns; others were ridden to take messages to the front or carry out reconnaissance. My father’s skills as a farrier were crucial. He once had a bad fall from a horse, getting his foot caught in the stirrup as the animal moved ahead, breaking his ankle. He had a lifelong limp.

In the first Battle of Ypres, in October 1914, horses were often swamped with mud and died on the battlefield. They sometimes became tangled in the enemy’s barbed wire and had to be shot. They suffered from fatigue, and terrible diseases like mange. The front line was terrifying for horses and men alike with its noise and chaos. My father never spoke of the horrors he had witnessed. My gradual realisation of their effect on him has taken many years. All I knew in my childhood was that there was no love or laughter or fun, or even a conversation, to be had with my father. He worked slavishly to keep us out of the workhouse. The price we all paid was that home was an unhappy, cold place where my earliest thoughts were of finding a way out.

In 1918, my father had returned to a Britain reeling from loss and sacrifice. Many families were missing their husbands, brothers and sons. There was mass unemployment and little government help.

Records show that 35,000 men from Coventry and Warwickshire went off to fight in France, many of them never to return. Our city was an important centre for munitions manufacture; all the car and cycles companies had been converted to help the war effort.

It was, ironically, a boom time for local industry. Men left to join the army, causing a huge shortage of labour. Women started working in the munitions factories for the first time and people began flooding in from other areas. The population of Coventry went from 119,000 to 133,000 in 1914.

Food shortages began to impact local families, as imports from abroad could not get through. Sugar, lard, flour and meat were hard to find and women began to form large queues outside city shops from early in the morning. Often there would be nothing but bones with a few ragged pieces of meat for them to buy once they reached the end of the queue. Boys were sent out as ‘watchers’ to scour the city streets looking for shops where there were some goods to buy. For a penny or two, one of them would save a place in the queue while his friend ran back to alert a housewife that it was a good time to go shopping. The government had not brought in rationing yet and some people were hoarding food. One woman was exposed in the local press for having bought dozens of bags of flour. She kept them in the bath where they got damp and maggots grew, ruining all of it.

Families were growing hungry and desperate, and their anger turned against a government refusing to recognise their problems and continuing to reassure the country that the war would be a short one. There were protests and strikes in Coventry calling for rationing so that everyone could at least share what was available.

In 1917, there was a huge demonstration in the city centre calling for ‘Equal food, Equal distribution’, with protesters holding up home-made banners and chanting slogans demanding rationing. The government could not afford to ignore the people of Coventry where key parts of the war effort were concentrated. By 1918, there was rationing of sugar, meat, butter and cheese.

Families were suffering from the absence of their men folk and the constant dread of bad news coming from France. Soon the Germans started to target inland towns from the air. The Zeppelin bomber was greatly feared. People had no air-raid shelters to flee to when this giant of the skies roared into view. The Germans were proud of their advanced technology. They had carried out many raids at sea using these airship bombers. Now they were aiming at civilians. The Zeppelin was a long-range airship with a metal frame, about 150m long and 18.5m in diameter, carrying a crew of up to nineteen, with seven or eight machine guns and 1,800kg of high-explosive bombs. It was powered by motors and kept afloat, lighter than air, by impenetrable bags holding hydrogen gas. It floated like a ship at a height of about 15,000ft. British planes might reach that height but had no bullets that could penetrate the bags and ignite the hydrogen gas.

It was an engineer from Coventry who invented the tracer bullet which would eventually help to bring them down. Flamboyant racing driver and engineer, James Buckingham, well known in the Spon Street area for his eccentric inventions and collection of home-made motors, studied the structure of the gas bags. They were made of cows’ intestines and had, until then, proved impervious to attempts to puncture them. Working alone, he developed an incendiary bullet which could puncture the Zeppelin’s bags, ignite spontaneously and set fire to the hydrogen gas inside. The Buckingham incendiary ammunition, combined with Pomeroy and Brock explosive bullets, was being used widely in Britain’s fighter aircraft machine guns by 1916, shooting down or destroying 77 of the 115 Zeppelins flown over Britain in attack raids. James Buckingham became a local and a national hero, and was awarded the Order of the British Empire at the end of the war, along with a £10,000 ‘thank you’ from the government.

Coventry was once again at the forefront of the war effort, from its munitions factories and massive workforce to its ingenious individuals with engineering skills. The city was proud of its Zeppelin hero and a new phrase came into being. ‘Doing a Buckingham’ was when you achieved something fair and square. Gradually, through advances like these, Britain gained the upper hand, and by the end of the First World War the Zeppelin had been rendered ineffective. By then it had claimed more than 500 lives.

Zeppelins had flown over Coventry on only a few occasions. Navigational aids were in their infancy and the Germans seemed unable to pinpoint the city accurately. The first to fly over the city, on 31 January 1917, found it in total darkness and flew on to Staffordshire to cause major destruction with its payload. However, an 80-year-old woman in Brooklyn Road, Holbrooks – my childhood home – suffered a stroke from sheer fright that night as she saw it in the sky, and died. Later, in April 1918, a Zeppelin dropped bombs in the grounds of Whitley Abbey and on the Baginton sewage farm. It had flown a successful raid after coming in from the Norfolk coast and dropping high-explosive and incendiary bombs as it headed towards the Midlands. Anti-aircraft guns opened fire but were unable to bring it down. By almost midnight it was over the grounds of Whitley Abbey where it dropped a 300kg bomb which smashed windows. Soon afterwards, two high-explosive bombs and nine incendiaries dropped on the sewage works and surrounding countryside, killing farm animals.

My father’s war in Belgium had been altogether bloodier and more calamitous. He was to come home to a city emotionally devastated by the loss of its young men’s lives. There was little to celebrate in the aftermath of mustard gas attacks, devastating battles at sea and the psychological wounds of a generation. His own family home was a doss-house down by Coventry railway station. Labourers from out of town, many of them poor immigrants who had left Ireland after the famine, paid 2d a night to literally sleep on a clothes’ line after a hard day’s work on the railways. Homeless, it was their only option. My father’s mother – my ‘witch’ of a Granny – rented out a room where 18–20 men would hang their arms and the top part of their bodies over a rope stretched from one end of the room to the other. Somehow, they would sleep like this, fully clothed, until five or six in the morning when the rope would be mercilessly cut. Granny wanted everyone out so she could accommodate those coming off a night shift.

There were thousands of similar common lodging houses in British cities at that time. Some were so cold that on occasions a man would be found frozen to death by the morning and would be carted off to a pauper’s grave. The dossers could buy a ‘penny mash’ from my Granny for their breakfast before heading to work. It was a spoon of loose tea and a spoon of sugar wrapped in a small twist of newspaper. They would empty it into a billycan of hot water, add some condensed milk, and hope for sufficient nourishment to get them through the morning.

These were hard times and they made for hard people. People like my Granny and my father who seemed to know little of love or kindness. He had no notion of how to bring that into family life.

He had lost his own father at the age of 3. Immediately after the First World War, the government launched an initiative encouraging young people to marry, to start families, to regenerate the broken country. My mother, quiet and submissive, had been a Sunday School teacher before she married. She was sensitive and musical, playing the organ at church and living a devout Christian life. Her basic education, along with her ten siblings, had been at a Ragged School, one of the benevolences of the Victorian era where children from poor working-class backgrounds could attend for free. Now it was the 1920s, when the creation of a large family was seen as almost a national duty. Britain needed to replace its workforce after the devastating loss of young men in wartime. There was no family planning and, at the same time, no welfare society to give support during the sharp rise in birth rates. My mother had one son and six daughters; I was the middle one, born in May 1929.

It was my mother’s kindness that saw us through the bleak early years of our childhood, praying with us each night before bed and saving us from the worst of our father’s wrath. We used to say the Lord’s Prayer and then a prayer of her own asking God to keep us safe through the night. Three of my sisters shared a bedroom with me, Granny in her own bed in the same room. Every sound would carry downstairs from the wooden floorboards. We had no rugs or carpets. We learned to keep perfectly silent once we had been sent to bed or there would be the whoosh of the cane as my father ascended the stairs. The slightest hint of chatter and he would enter the room, laying the cane firmly down on the bed as a warning of more to come if we continued.

Granny and my father’s brother, Uncle Phil, lived with us throughout my childhood. Their only alternative had been the workhouse in Gulson Road where hundreds of paupers were accommodated. A red-brick edifice which later became a hospital and is today the engineering faculty of Coventry University, it was a constant menacing presence in the 1930s. A silk mill operated inside the workhouse, using penniless men, women and children as its labourers. Nine-year-old children would receive the same pay as adults – they were allowed to keep one penny out of every shilling they earned in a ten-hour day, six days a week. The location was a byword for destitution in Coventry. A man offered a poorly paid job would know: ‘It’s this or Gulson Road.’

Granny had become too old and infirm to run the doss-house any longer. My Uncle Phil, in his twenties, also needed a home. He was an amiable presence, good fun and kind to me and my sisters. I remember him giving me a ride on the handlebars of his bicycle, and often offering a handful of sweets or a penny. But Granny was nothing less than a tyrant who could barely tolerate our existence. There were sharp words and smacks, and one day I saw her throw a full scoop of water from the laundry boiler at my mother after an exchange of words.

My sisters and I flinched from these frightening episodes. We would often listen to the sound of persistent angry complaints from my father towards my mother as we lay in bed. One night, the angry murmur seemed to escalate and when we heard a muffled scream my sister Anne, a little older than me and my closest sibling throughout her life, crept out to the upstairs landing. She saw my father holding a knife to my terrified mother’s throat, both of them standing against a wall near the open sitting-room door. My father moved away when he saw Anne. We cried ourselves to sleep. This was no way to live.

Of course, there was the comfort of a close bond between us children. My mother gave birth to all her babies at home and I remember coming back from infant school and twice being ushered into her bedroom to see my newborn sisters. There had been no fuss during the pregnancy, no let-up that I can remember in my mother’s daily chores. No fuss or screaming during the pain of labour; it was my poor mother’s lot to accept the weariness and drudgery of a household where money was always tight and marital love and care even tighter.

Our home was a brick-built semi with three bedrooms, an indoor bathroom but outside toilet, and a useful yard where my father kept a horse. Hard-working and enterprising, he had set himself up in business doing house removals. The horse pulled carts full of furniture and possessions. He would respond night or day to a customer needing his services urgently. These were ‘midnight flits’ where a family had packed up and left without paying their rent. My father would move them to their new lodgings, no questions asked.

He also swept chimneys and hauled coal, stacking it in the yard where customers filled their own sacks. He was often covered in soot and grime, his work clothes black with dirt. He shod horses too, wearing a worn leather apron.

Dad was also something of an entrepreneur. He had bought up several old terraced houses in the poorer parts of Coventry, and even owned two shops in Spon Street in the city centre, running them as a greengrocer’s and flower shop, and a corner grocery store. In our day this location was run-down. It was hard to see any future worth in the dilapidated buildings, neglected since the Middle Ages. There was no cachet at all in being a shopkeeper there. Continual patching up of the roofs and masonry and the cost of employing staff were a constant drag on my father’s finances.

Today he would be astonished to know that Spon Street is preserved as a medieval jewel and one of Coventry’s major tourist attractions with its lovingly restored half-timbered buildings. For my father, the ownership of these houses and shops was a drain on his energy and the cash bank-roll he kept in his back pocket. Today his business acumen would give him status and even wealth. But in 1930s Coventry his ‘investments’ were the sources of stress and strain. Somehow, he had learnt the value of savings and the need to plan for the family’s immediate financial needs. Perhaps the grim experience of his mother’s doss-house had instilled that in him. And despite his many small enterprises it was a continuous struggle to support eleven of us in the family home. Sadly, although he did manage to keep us safely housed, clothed and fed, he had no notion of paternal love.