59,44 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seoul National University Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In the first book-length study of Brazilian gangster funk in English, the author draws on a unique combination of ethnography and community activism undertaken across several years living and working in the favela of Rocinha—one of Rio’s largest—to explore its rise. On the surface, the core narrative he identifies pits favela residents against the middle and upper classes of mainstream Brazilian society. At a deeper level, though, he interprets it as a story of a communally oriented Afro-Atlantic worldview versus the dehumanizing colonialist and imperialist one. Brazilian gangster funk is an expression of the utopian edge of Rio’s urban youth culture pointing towards an improbable, yet powerful sense of hope for greater coexistence, not only for young people in Rio’s favelas but for all of us anywhere.

Brazilian funk has its origins in the dance parties of the young, mostly Black and racially mixed poor inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro in the early 1970s, set to the sounds of African American soul and funk. The music of these bailes funk evolved along with the advent of electronic music and hip hop—primarily through the influence of styles like electro funk, freestyle dance and Miami bass and groups and artists like 2 Live Crew, Grandmaster Flash, Stevie B and DJ Battery Brain. Due to the mass gang fighting at many dance halls across the city’s low-income suburbs in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the bailes funk relocated to Rio’s informal, low-income favela communities. There, funk carioca underwent a crucial shift as local MCs and DJs began performing in Portuguese to address the daily lives of Rio’s poor youths. They also started playing proibidão, as Brazilian gangster funk is called in Portuguese, often in homage to the criminal factions who ostensibly controlled those communities and hosted the parties.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 660

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

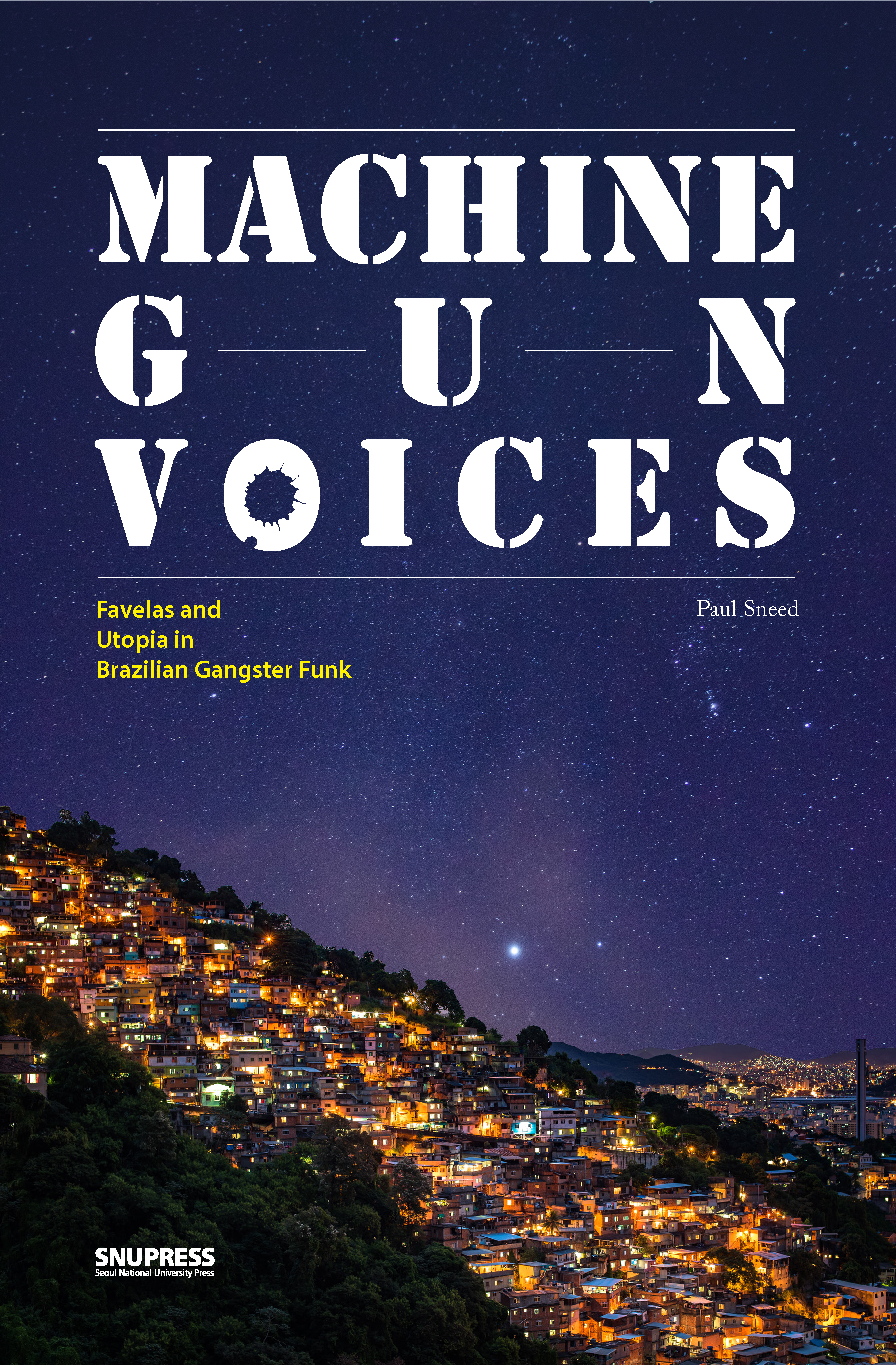

Machine Gun Voices

Favelas and Utopia in Brazilian Gangster Funk

Copyright © 2019 Paul Sneed

ISBN 978-89-521-2949-9 95380

All rights reserved. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any form or by any means, except for brief quotations, without written permission from Seoul National University Press.

Seoul National University Press

1 Gwanak-ro, Gwanak-gu, Seoul 08826, Republic of Korea

E-mail: [email protected]

Homepage: http://www.snupress.com

Tel: +82-2-880-5252

Fax: +82-2-889-0785

Contents

Photo Gallery

Foreword by Carlos Palombini

Chapter 1

Funk Rio

Chapter 2

Machine Gun Voices

Chapter 3

Writing about Funk Carioca

Chapter 4

Proibidão and Rio’s Gangs

Chapter 5

Rocinha Favela

Chapter 6

Crimes of Self Defense

Chapter 7

Social Bandits in Funk

Chapter 8

Bandits of Christ

Chapter 9

Trafficking Culture

Chapter 10

Musical Survival Tactics

Chapter 11

Utopias de Favela

Chapter 12

Mixes from the Margins

Chapter 13

Last Dance

Afterword

Appendix

Foreword

Funk carioca culture originates from the young proletarians of the greater Rio de Janeiro city who united to dance to the sounds of African-American soul in the early 1970s. Unlike the English club culture known as Northern Soul, Brazilian soul people shared with their North-American peers a common African heritage, but not a common language. In the course of two decades, their musical tastes evolved with African-American music—from soul to funk, Philly soul, disco, hip-hop, electro funk, electro, Miami bass, Latin freestyle—until a hybrid of song and electronic dance music (EDM) emerged (Palombini 2014). Funk carioca arose from a club culture, but the closure of suburban venues by law enforcement agents in the latter half of the 1990s sent it back to the favelas where it found a new home and exploded even more.

Paul Sneed lived in the favela of Rocinha, in South Rio, as a University of Virginia undergraduate student on an exchange programme in 1990. He returned for extended stays in 1992 and 1995, for research experiences as a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin in 1996, 1998 and 2000, and for fieldwork in 2001, 2002 and 2003, adding up to some five years of residence (not including subsequent stays and research stints in Rocinha). He was thus able to gain in situ knowledge of the newborn music, with its early waves of popularity in the media, of which the first, in 1995, coincides with the golden age of funk consciente(‘conscious rap’), whereas the second, in the year 2000, is coetaneous with the ascendancy of the subgenres putaria(‘whoredom’) and proibidão(‘forbidden funk’).

Proibidão is commonly described as apologia(‘apology’) with ellipsis of the object that this music would eulogize. Such an object is tacitly understood to be crime, sex or both.1Strictly speaking, the subject matter of proibidão is ‘crime life,’ where ‘crime’ stands for the trading of illicit substances conductive to altered states of consciousness, especially marijuana, cocaine and crack, with the exemption of those activities of this trade that take place outside the favela or are not conducted by people associated with it. The remainder of this operation is termed ‘drug dealing,’ so that the lower echelons of the drug business substitute for the upper ones insofar as liability to punishment is concerned. The rhetorical expenditure of this naming strategy, in which pars pro toto (‘a synecdoche’) hides behind an ellipsis, is inversely proportional to the legitimacy of the measures wherewith the music is penalized, hence the ironic hyperbole of the augmentative (the term proibidão translates as ‘forbidden big thing’) — yet another double figure of speech. Proibidão is best defined as the subgenre of funk carioca that deals with life on the retail end of the illicit substance trade, narrated with specific ethical concerns, from the perspective of those who experience its problems, according to a particular aesthetics of composition, performance, and musical and phonographic production.

One of the main representatives of the subgenre, MC Mascote, from the favela of Vidigal (facing the sea on the thither side of the same Dois Irmãos rock on whose slopes part of Rocinha stands), states that the first proibidão was “Rap do parapapá,” by MCs Cidinho and Doca, from the West Rio favela of Cidade de Deus, in 1994.2The following year, the repercussion of “Rap das armas,” by MCs Júnior and Leonardo, from Rocinha, turned proibidão into a public security affair.3Thinly veiled allusions to life in crime made it onto vinyl without further ado in the 1990s, while explicit pieces, recorded live during funk dances, circulated on MDs and cassette tapes. In 1998 Bonde do Lambari(“Lambari Crew”), from the North Rio favela of Jacaré, was probably the first CD to feature proibidão prominently among its tracks.4On September 9, 1999 a copy of the CD Proibidão do Rap appeared when the police raided Fazendinha, in the Alemão Complex of favelas, in North Rio, and arrested 20-year old MC Sapão, who unwittingly hit the mainstream press as an alleged drug dealer in the following days (“Apreensão” 1999; Oliveira 1999, 17); on November 16th, another raid, this time in Vila Cruzeiro, in the Penha Complex of favelas, also in North Rio, led to the discovery of Proibidão do Rap 2(“O brinde musical dos traficantes” 1999).5

The year 2000 saw the proliferation of such CDs, their circulation soon enhanced by peer-to-peer file sharing networks (Soulseek), file hosting services (4shared, MegaUpload, RapidShare), social networking websites (Orkut, Facebook), webcasting, blogs, photo-logs and file-streaming services (SoundCloud). YouTube eventually became the main distribution outlet, proibidão hits reaching views in the range of eight-digit figures therein. Recorded live at Chatuba, in the Penha Complex, on July 26, 2009, “Vida bandida,” by Praga, sung by MC Smith and produced by DJ Byano, epitomizes this acme, the poignancy of its refrain rendered barely bearable by DJ Byano’s humorous touches: “Hoje somos festa, amanhã seremos luto” (“Our life is bandit and our game is tough, today we are party, tomorrow we shall be mourning”). Yet the extent to which this music relied on the circuit of favela dances started to become clear as the infamous Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) policy began to supress them from 2008 onwards.6The military invasions and occupation of the Penha and Alemão Complexes in November 2010 (Caceres, Ferrari and Palombini 2014, 160–177) as well as the illegal jailing of MCs Frank, Max, Tikão, Dido and Smith in December dealt a severe blow (Palombini 2013). The Chatuba dance, which had been the epicentre of proibidão during that decade, ceased its activities and the subgenre started to move in different directions (Facina and Palombini 2017).

In tracks like “Papo de bandido” (“Bandit’s talk”) and “Tá tudo monitorado” (“It’s all monitored”), produced by DJ RD da NH, MC Rodson (2011, 2012) resorts to elusive syntax, ellipses and coded language; in “Rotina de patrão” (“Boss’ Routine”), produced by DJs Rennan and Isaac 22, MC Smith (2011) explores the ambiguity of the bandit figure, as does MC Orelha (2013) in “Herói ou vilão” (“Hero or Villain”), produced by DJ Diogo do Serrão; in “Vida bandida 2” (“Bandit Life 2”), written by Praga and produced by DJ RD da NH, MC Smith (2013) incarnates a jailed bandit who ponders on his life. Some artists stuck to the explicitness of the old style, replacing rival criminal factions with the State as the target of their invectives. Thus, in 2011 MC Vitinho released “Bala na Dilma sapatão” (“Bullets at [President] Dilma, the Dyke”), produced by DJ Rafael da Coruja, and in 2014 MC GEELE recorded “Na Copa do Mundo quem vai vencer é o CV” (“In the World Cup the Red Command Shall Win”), produced by Estúdio Criminoso.7

With his doctoral dissertation, presented at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2003, Sneed became the first scholar to devote his efforts to proibidão. The Master’s theses of Carla Mattos (2006), Rodrigo Russano (2006), Maurício Guedes (2007), Eduardo Baker (2013) and Dennis Novaes (2016) followed suit. Some, including Guedes, have concluded that “… proibidão is the spokesperson of the drug-dealers’ factions…” (Sneed 2007). Sneed’s view is different. By focusing on the creation of a collective time-space of power, knowledge and existence, rather than on leaders or lyrics, in this present work (which is an outgrowth of that earlier dissertation) he reaches the insight that proibidão is a symbolic site in which the expectations of community residents vis-à-vis illicit substance retailers—and vice-versa—are both articulated and mediated. With this publication, Machine Gun Voices now figures alongside Carlos Bruce Batista’s 2013 interdisciplinary anthology as one of the two published volumes on this music around which some of the most pressing issues of the times converge—and the first in English.

On December 15, 2010 images of the arrest of MCs Frank, Tikão and Smith by a sheriff turned into TV-star invaded Brazilian homes as an epilogue to the latest and most spectacular episode of the Global War on Drugs. Since then, a never-ending series of violations of rights has been perpetrated against MCs, DJs, sound-system owners and funksters in general. If this can happen to artists who enjoy the love of millions, so I thought, it could happen to anyone else. In response to the popular uprising of June 2013 the middle-classes have become acquainted with a somewhat milder version of such treatment. The following year, the Operação Lava Jato (or “Car Wash Operation,” the famous investigation into corruption at the forefront of Brazilian politics over the past decade) started to familiarize a selected few members of the élite with an even more polite one. Sneed’s work shows one way out of the impending danger: communion with the lives, culture and artistry of those who, from time immemorial, have been suffering oppression in its crudest state.

Carlos Palombini8

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil

1 In the case of sex, the precise name is putaria; see Raquel Moreira, “Bitches Unleashed: Women in Rio’s Funk Movement, Performances of Heterosexual Femininity, and Possibilities of Resistance,” and Mariana Gomes, “My Pussy é o Poder. Representação feminina através do funk: identidade, feminismo e indústria cultural.”

2 Personal communication to Foreword’s author (Carlos Palombini), August 26, 2015.

3 A radio-friendly version of “Rap do parapapá.”

4 I (forward’s author Carlos Palombini) am grateful to DJ Leandro Baré for calling my attention to this CD, and to DJ Pedro Fontes for giving me access to it.

5 News about these raids was discovered by Adriana Facina during archival research in the National Library and mentioned in personal communication to Foreword’s author (Carlos Palombini, nd).

6 Pacifying Police Units were designed to militarily occupy favelas located in highly valued neighbourhoods as part of preparatory efforts towards the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games, as well as of a wide process of urban gentrification.

7 The CV is one of the three main associations of illicit-substance retailers, or facções (‘factions’), and the one most closely associated with proibidão culture.

8Carlos Palombini is Professor of musicology in the school of Music of the universidade Federal de Minas Gerais(UFMG), fellow Brazils National Research Council(CNPq) and associated faculty of the graduate program at the Universidade Fedral do Estado do Rio de Janeiro(UNIRIO)

Favela Street Party1

It’s a muggy summer night after three A.M. on a Saturday in early 2002 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. At the foot of the favela of Rocinha, heavily armed gangsters are throwing an enormous outdoor funk dance party in the middle of a narrow street called the Via Ápia. Booming electronic music flows from the towering speaker stacks running along the side of the slender road, one of the primary commercial strips in the grid-like lower area of the favela. Despite the late hour, thousands of young people circle to and fro in long train-like lines, moving up and down the street as the subwoofers blast music loud enough to rattle the glass out of some nearby windows. Under a makeshift canvas awning, off to one side, drug-traffickers cluster in the dim light around tables jam-packed with money, guns and packets of cocaine and marijuana of different sizes. Others patrol in small bands, machine guns brandished as they move slowly through the crowd, serenely taking in the scene and making sure no fights break out.

This type of street baile is a sort of community festival that attracts people of all ages, including many who would never consider themselves funkeiros, as such, as one calls fans of Brazilian funk. Though most are in their teens and early 2000s, a significant number of those present have not yet hit puberty. Just in front of us, scattered groups of kids as young as seven and eight cheerfully perform choreographed dance moves with one another. A surprising number of middle-aged people gather along the storefronts and small restaurants lining the street—and even some elderly folks besides—drinking, laughing and playing cards in the mouths of the network of alleyways intersecting the larger road. In any case, since this baile funk(as these dance parties are called in Portuguese) is outdoors, there is no clear physical division or barrier between where it begins and ends. As a result, even those neighbors inside the homes up and down the Via Ápia and the surrounding areas of the favela also find themselves in its midst, like it or not. Try as they might to close up their residences, padding their doors and windows with towels and blankets, running fans, blaring their TVs, even households a considerable distance away literally tremble to the pervasive throbbing blast of the surrounding electronic soundscape.

Even when there are no dances in the Via Ápia, twenty-four hours a day it is one of the most bustling areas of Rocinha. Buildings as many as five and six stories tall line both sides of the street, which gently slopes up the base of the Morro Dois Irmãos (‘Two Brothers Hill’), a famous granite-peaked, forested mountain visible from the posh beaches of Rio’s Southern Zone. By day, hundreds of motorcycles, taxis, trucks and cars speedily squeeze past one another along the Via Ápia as hundreds more people enter and leave the favela on foot. At those times, countless more stand off to the sides, conversing with friends and neighbors. The street runs slightly uphill from the entrance of Rocinha past the numerous bars, restaurants and other businesses lining it along both sides, including small furniture stores, bingo halls, hair salons and stands selling hot dogs, corn on the cob and pirated CDs and DVDs. On nights when there are not dances here, skinny, unarmed teenage drug dealers talk in small groups, keeping a lookout for customers and the police.

Tonight the celebration being thrown by Rocinha’s drug traffickers in the Via Apia is what funk fans in Brazil call abaile de comunidade(‘community dance party’). It is a type of open-air baile funk held in favelas in the streets, alleyways, soccer courts or bus depots of the neighborhood.2I am standing shoulder to shoulder with a small group of friends from the Cachopa area of the favela, where I have lived off and on for several years during my frequent but sporadic periods of residence in Brazil. Orlando, Vítor and Cícero, all in their mid-2000s, smile as they sway gently to the beat, scanning the crowd for other friends and neighbors. The music of the baile is so loud that it forces the people at the dance to speak from a very close distance, as they hug, clasp one another’s hands enthusiastically and exchange beijinhos—as the little kisses often used by women and members of the opposite sex are called.

The crowd mixes along the narrow strip in two currents. One heads up to Rocinha’s main thoroughfare, the Estrada da Gávea, where Planet Pizza and the Cabaré do Barata are doing booming business. The other stream flows down toward the entrance of the favela at the Passarela pedestrian footbridge, near the tunnel and the high-speed Lagoa-Barra freeway just below. The dense masses of people moving in either direction make it slightly difficult to breathe, let alone dance. Even so, people everywhere gently sway as they chat and smile nonchalantly. Others perform dance moves off in the small spaces to the sides and on either end, facing the line of stacked amplifiers along the edge of the street.

The heavily armed soldados(‘soldiers’), as the armed favela gangsters are called, of the local drug cartel can be seen wading through the crowd or standing in the openings of alleyways, dressed as the other funkeiros but flashing weapons such as AK-47s, AR-15s, shotguns, pistols and Uzis.3One gangster wearing a rubber Osama Bin Laden mask accepts a fat, smoky marijuana joint from another, taking care to balance his assault rifle straight up in the air with his other arm so as not to accidentally shoot anyone.4Adhesive stickers of the Flamengo soccer club are visible against the silver plating of his weapon. The drug traffickers talk in groups as they eye the crowd, keeping watch and swaying to the thudding beat of the funk music. Fighting is uncommon at the bailes funk in the Via Ápia, because to cause trouble of any kind would be an offense to these same gangster hosts that are throwing the party. Still, one never knows what can happen at any funk dance party and my friends and I pay careful attention to the multitudes of people pressing against us in the ever-shifting crowd.5

The baile is hot and humid in the summer night, despite being outdoors, and the air hangs thick on the crowd, filled with smoke, the smell of sweaty bodies and even some gasoline exhaust from vehicles in the cramped side alleys off the Via Ápia. I’m filled with a sense of joy and expectation as people with smiling faces pass by shouting the words to the music, chanting and swaying sensually to the songs. On the small black, plywood platform by the speaker stacks, fireworks explode in flaming fountains as the stage lights flash and a smoke machine pours out columns of smoke. The MCs have not yet taken stage there and a DJ is playing the summer’s funk hits. He starts with a montage titled “5 Caras” by the Bonde do Vinho. Next, we hear a familiar refrain popular in Rocinha of a song by MC Dollores (Aldenir Francisco dos Santos), one of the all-time greatest Rio funk singers and a life-long Rocinha resident. The chorus, “‘O Bigode’ é quem comanda a favela da Rocinha!” (“‘Moustache’ is in charge of the favela of Rocinha!”), makes reference to the favela drug gang’s boss, Lulu (Luciano Barbosa da Silva), who was slain by police in 2004. Next comes the song “Paga Spring Love,” by Fornalha, another Rocinha MC at the height of his popularity. Suddenly my friend Josivaldo, from the Cachopa area of Rocinha, appears in the crowd in front of me and clasps my hand enthusiastically, slapping me on the back several times. He has come upon the dance on his way over to his girlfriend’s house across town in Taquara and has been lingering in the street, taking in the scene and talking with friends.

The baile funk is its own kind of high. Drinking, smoking marijuana or snorting cocaine might heighten the experience for some of the people in attendance, but one need not be drunk or high to feel the energy of the masses of squirming bodies and the barrage of bass pulling the crowd back and forth to the beat. Despite the enormous volume of the music and the multitude of thousands jamming itself into the proportionally small street, the baile de comunidade in the Via Ápia is beautiful and I begin to feel a sense of great peace and belonging overtaking me. The music and the crowd itself are so loud that they somehow drown everything else out, leaving me with a quiet sense of awe. The sound of the heavy bass and electronic beats of the music echo across the slopes of the favela as those of us in the crowd blissfully swim in the sonic waves of a favela funk utopia.

With its population estimated at over 100,000, Rocinha is considered one of the largest of the hundreds of favelas in Rio.6Due to its size and location in one of the wealthiest parts of the city, Rocinha receives considerably more attention from the city government than most other favelas and has grown commercially at an astounding rate over the last few decades.7Still, given the limitation of its physical space relative to its vast population, Rocinha is one of the most densely populated places on Earth and remains sadly lacking in adequate sewage, water, electricity and educational resources.8Throughout much of its history, police have done little policing in the neighborhood and, instead, residents have relied upon local drug-traffickers to provide law and order.

Rocinha has always been one of the most important communities for the movimento funk(‘funk movement’) as folks often called it back then. Many of funk’s most famous old-school MCs came from Rocinha, like MC Galo (Everaldo Almeida da Silva), Neném (Anderson da Silva Ângelo), Gorila and brothers Leonardo (Leonardo Pereira Mota) and Júnior (Francisco de Assis Mota Júnior)—none more exceptional than the aforementioned MC Dollores. Funk melody, a romantic, bubblegum version of funk, was also crucial in Rocinha, which was the home of the composer Renato Moreno and the singer Charlys da Rocinha, who performed songs in Portuguese, Spanish, English, French and Hebrew.9There were at least four large-scale bailes held weekly in Rocinha, each one attracting thousands of funkeiros, in addition to the events held for holidays and other special occasions. The most famous was at the Emoções club. Another was at the old samba quadra(‘practice hall’) on top of the favela at Rua Um. One took place along the open-air sewage duct of the Valão area near the base of the hill (and the most active location for illicit drug sales at the time) and the last was the baile in the Via Ápia described above.

Rio’s Funk Carioca

With its booming bass and pulsing electronic beats, throaty vocal delivery, frenetic samplings and playful, sensual dance moves, Brazilian funk has much in common with its close cousin, American hip-hop, Latin reggaetón and Jamaican dancehall are also close relatives.10Though these are all Afro-Atlantic, urban electronic music styles with many common roots, funk carioca, as it is also known (carioca is used to describe someone or something from Rio de Janeiro), is far from being a mere imitation. It is a rich and uniquely Brazilian musical culture with its own distinctive ways of walking, talking, dancing and making music.11The bailes funk, like the dance party described above, also have a distinctly Rio way of coming together. Incorporating counter-cultural aspects of the broader Black Atlantic world and the international Black Movement more and fusing them with the culture of the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, funk carioca, since its beginnings in the early 1970s, has evolved into a vibrant musical youth expression characterized by irony, complex masking and subversive messages and practices.12At once heroic and delinquent, a cry of protest and resistance, an apology of crime, a cheap and sexualized commodity and a call to gather together in community, to love, to fight and to live, Brazil’s funk is a weapon in a postmodern war.

Since the later years of the twentieth-century funk carioca has maintained undeniable significance for millions of poor urban youth, who continue to identify with it to this day. Hundreds of thousands still attend the enormous funk dance parties each week in the streets and samba clubs of the favelas where they live. Indeed, these bailes funk have come to be emblematic of the world of Rio’s favelas today. It is a world existing on the front lines of police violence and gang wars, poverty and stark inadequacies, yet still one made up of resilient people confronting the harsh conditions of their daily lives with humor, love, courage, perseverance and music.

Musically, Brazilian funk is a rich blend of beats and diverse pre-recorded samples of everything from machine gun fire and explosions to digitally enhanced voices, radio sound bites, Brazilian cowboy calls, animal noises and anything in between. It is as unashamedly eclectic as the culture of the favelas of Rio de Janeiro within which it has arisen, mixing the melodic structures of other Brazilian musical styles such as axé, forró and samba—even the Afro-Brazilian martial art/dance form of capoeira—with features of international music like R&B, techno, hip-hop, pop, rock and even Contemporary Christian Music. Rio Funk MCs perform singing more than rapping, often calling out in hoarse, throaty voices, sometimes almost yelling as they chant out refrains reminiscent of the mass cheers at soccer games in the Maracanã stadium on the north side of Rio.13

MCs have been singing lyrics in Portuguese since the mid-1990s, when several of the Rocinha singers first came to prominence, as did those in neighborhoods like the Cidade de Deus, the favelas of Borel and Vidigal and countless other communities. Some, like MC Galo, female MC Taty Quebra-Barraco (Tatiana dos Santos Lourenço), Deize Tigrona (earlier known as Deize da Injeção), MC Sabrina (Sabrina Lindalva da Cruz Credo, one of the early female figures associated with proibidão), Bob Rum (Moisés Osmar da Silva), D’Eddy, and Mr. Catra (Wagner Domingues Costa) performed mostly as solo artists. Others, like Cidinho (Sidney da Silva) and Doca (Marcos Paulo de Jesus Peizoto), Leonardo and Júnior, Markinhos (Marcos Ribeiro Chaves) and Dollores (Aldenir Francisco dos Santos), William (William Santos de Souza) and Duda (Carlos Eduardo Cardoso da Silva) and Claudinho (Claudio Rodriques de Mattos) and Buchecha (Claucirlei Jovêncio de Sousa) generally performed in duos. Others started as duos, like Mascote (Fábio de Oliveira Cordeiro) and Neném, later to perform as solo acts. MC Serginho (Sérgio Braga Manhães) sung with his transgender dancer and partner Lacraia (Marco Aurélio Silva da Rosa). Still others performed as lead vocals for backing groups often called bondes, like Valesca Popozuda (Valesca Reis Santos), of the girl group Gaiola das Popozudas, a group that formed in 2000 but achieved national fame beginning in 2007. Although they touched on a range of topics too broad to define, many of their songs were of a romantic, sexual, violent, humorous or consciousness-raising nature. Even in those early days, lyrics could touch on everything from appealing to violence and raw sexuality one moment to brotherly love, peace and faith in God the next. Whatever the songs of funk have been about—then or now—they have been written by and large by and for people living in Rio’s favelas and the city’s other low-income neighborhoods. They have been, not surprisingly, mostly about the lives of such people and their love, passion, beauty, strength, faith, sensuality, sexuality and creativity.

In that first wave of funk songs with lyrics in Portuguese in the mid-1990s, one prevalent feature in songs was to enact a radical inversion of the social geography of Rio de Janeiro. Rejecting the traditional superior value given to middle and upper-class neighborhoods like Copacabana, Ipanema, Leblon and Lagoa, commonly referred to in Portuguese as bairros nobres(‘noble neighborhoods’) songs instead proclaimed the favelas as the quintessentially Brazilian social spaces—and indeed quintessentially pan-human ones. This tendency was particularly evident through the mid-1990s through early 2000s, in what I consider the heyday of the community dance parties—like the one described in the beginning of this chapter–that took place in that favela. It was a common feature in funk songs at the time to include lengthy, fluidly arranged lists of the names of favelas. An excellent example of this tendency was in the song “Nosso Sonho” (“Our Dream”), by the bubblegum pop-funk duo Claudinho and Buchecha, a hit in 1997. The song’s title, too, is well in keeping with the utopian impulse at the heart of funk carioca analyzed in this study. 14

Beginning in the 1990s, distinctions arose between categories of the funk (pronounced ‘funkee’ in Portuguese). Montagem(‘montage’) used heavy samples and electronic beats with highly repetitive lyrical phrases and refrains. Rap was a lyrical form of funk which, despite the name, almost never actually included rapping, per se. Funk melody, the variety performed by Claudinho and Buchecha, mentioned above, was similar to the sound of Rio’s charme scene, a close cousin of funk carioca popular in those early days. Into the early 2000s, the array of funk subgenres grew to include proibidão, a sort of forbidden, underground gangster rap, putaria, which literally means ‘whorishness’ (often euphemized as funk sensua l).15More recently still, it has expanded to include funk ostentação, (‘swag funk’) associated mostly with funk carioca as it has developed in São Paulo. Today one also hears of funk de raiz, literally meaning ‘root funk,’ a sort of consciousness-raising, throwback style used as a platform for a social justice agenda, and even an Evangelical Christian variety of funk carioca known as gospel funk.16

Given the richness and complexity of Rio’s funk, the best sound or video recordings are not truly capable of transmitting the full experience of the musical culture but are instead more like photographic snapshots. The same is true when it comes to books like this and even TV shows, films and documentaries about funk. Even so, for those interested in getting a sense of what funk carioca is about, one might start with Denise Garcia’s 2005 Sou feia, mas tô na moda or Wesley Pentz (DJ Diplo) and Leandro HBL’s 2008 Favela on Blast. Despite its age and the many changes occurring in funk culture over the past two decades, Sérgio Goldenberg’s pioneering film in 1994, Funk Rio is still arguably the best example of Brazilian funk videography, for its emphasis the lives of ordinary youths in and around the bailes funk.16

One of the most widely-viewed funk documentaries, with over a million views on YouTube, is 2018’s fan film Documentário Mc Zoi de Gato (A Voz da Favela), by internet influencer Kelvy Lopes. It tells the story of MC Zoi de Gato (Denner Augusto Sena da Silva), a brilliant pioneer of proibidão in São Paulo who died in a car crash, merely sixteen-years-old, in 2009. If viewers can be patient enough to sit through the meandering first hour and a half of the film, the final fifteen minutes is deeply moving, and even reminiscent of Sérgio Goldenberg’s relational film style. It highlights the inauguration of a giant graffiti memorial to the MC, where Denner’s mother, dona Kátia, is presented with an illustrated portrait of her son. The scene takes place as a surprise to dona Kátia, who is brought in blindfolded before hundreds of neighbors to a small plaza in the MCs community of Vila Natal, along the working class periphery of São Paulo. Meanwhile, his hauntingly beautiful underground hit “Amor é só de mãe” (“Love Is Just from Mothers”) plays in the background.17

Ultimately, what makes it so difficult to encapsulate the culture of funk carioca in print, sound recording or video representations is that it is primarily one of live performance, despite its explosive growth in cyberspace and social media since the early 2000s. Indeed, the real space-time of funk carioca comes together in the lives of the people who join together to create it—especially within the reality of the baile funk dance parties themselves, live and in color, in the midst of thousands of sweaty dancing bodies and the thunderous bass of the wall of speakers. More than a beat or musical style, Rio funk is in many ways the transformation of the sounds and realities of the favela themselves into music, dance and song—heightened and intensified in the bailes funk. As local expressions of the larger, historical Afro-Atlantic world, over time I have come to understand these dance parties as community encounters in the everyday life, religious and musical practices of the youth culture of the residents of Rio’s favelas, as African Diaspora peoples.18As community encounters, the reality of these spaces is limbic besides, making them not only hideouts from hegemony protecting them ideologically but as safe havens strengthening them psychologically and even physiologically.19

Rio’s funk scene has evolved over the past few decades into one of the country’s most vibrant musical expressions—this in a country well-known for its rich musicality. Even so, it continues to be one of the least understood by people outside of the favelas and other poor communities where it is most famous, not only abroad but also among the greater Brazil public. Its reputation as a violent and socially irresponsible form of music involving overly explicit dance moves, superficial lyrics, low-end levels of music production and frequent references to Rio’s infamous criminal factions has made it difficult for outsiders to consider funk carioca in a sympathetic light.

Amidst those booms of funk carioca in the mid-1990s and early 2000s, media representations of funk were common, though scholarly analyses were still few. Many of the initial media coverage of Rio’s funk tended to either romanticize or vilify it, generally in either a sensationalist tone or an exotic one (Herschmann 2000). Funk carioca’s reputation for violence and overt sexuality made it, according to the New York Times in 2001, “perhaps the most controversial dance scene in the world” (Strauss 2001, 29). The following year, the Washington Post reported that “The ‘funk balls’ of Rio are pantheons of pleasure and violence that have gained international renown as the world’s fiercest urban dance scene. Brazilian funk—inspired by the sounds and styles of American gangsta rap and hip-hop but far more extreme than either—and the balls where it is played are the most controversial craze yet in Latin America’s largest nation (Faiola 2001, C7).” That same year, Brazilian investigative reporter Tim Lopes—of Brazil’s leading television network, Globo—was discovered by drug traffickers as he filmed their activities inside a funk dance in a favela in Rio de Janeiro. The events surrounding the brutal torture he suffered and his murder shortly after that invigorated the debate about funk and its connections to the growing crisis of violence and social exclusion in Brazil (Souza 2002).

Over the years, scholars writing about funk carioca have wrestled with its demonization in mainstream Brazilian media and society, starting with the very first research publication about funk, anthropologist Hermano Vianna’s O mundo funk carioca(1988). A decade later Micael Herschmann provided an in-depth communications-based analysis of this issue early on in his edited volume Abalando os anos 90(1997) and in his single-authored follow-up book O funk e o hip-hop invadem a cena(2000). Over the course of time, journalists like Sílvio Essinger, author of Batidão: Uma história do funk(2005), and Júlio Ludemir, author of 100 Funks que você tem que ouvir antes de morrer(2013), have also written about this problem. So, too, have leading scholars of funk today like Adriana Facina and Carlos Palombini, co-authors of “O patrão e a padroeira: festas populares, criminalização e sobrevivências na Penha, Rio de Janeiro” (2016). Funk activists, like brothers MCs Leonardo and Júnior, themselves similarly decry the problem, , as is recounted in Adriana Lopes’ Funk-se quem quiser(2011)(see, for instance, the preface by MC Leonardo, 13-17), and in Mariana Gomes Caetano’s equally penetrating—and hotly debated—Master’s thesis “My pussy é o poder: Representação feminina através do funk: Identidade, feminismo e indústria cultural” (2015). Together these sources offer useful historical perspectives on the development of funk carioca, as well.

Eventually, defenders of funk carioca would take the debate all the way to Rio’s legislature, where they were finally successful in getting a law passed that recognized funk as one of the city’s most significant cultural manifestations. The session was presided over by the well-known human rights advocate and Rio representative Marcelo Freixo, of the Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (PSOL). Other advocates who presented arguments in favor of funk included: anthropologist Hermano Vianna, the pioneer of studies of funk, anthropologist Adriana Facina, one of the most active funk scholars/activists today; famous Brazilian white pop/MPB singer Fernanda Abreu; MC Leonardo, renowned Rocinha funk singer from the `s. With his brother, MC Júnior, Leonardo is co-founder of Apafunk (Associação Profissionais e Amigos do Funk), an organization that, besides defending funk, advocates for the rights of prison inmates and favela residents.20 Despite such legal recognition, however, funk carioca continues to be the most controversial musical style in Brazil today.

Machine Gun Voices20

My first contact with funk carioca occurred in 1990, during my initial period of residence in Rocinha, a favela that would eventually rise as one of the cradles of the style as it is known today. At the time, I was an undergraduate student from the US researching in Rocinha; my research was not about funk, per se, but the about views of residents of Rocinha on the favela’s powerful drug gang and what they called the “law of the favela.” I still remember the first time I ever heard funk, one night late as the music and live singing came booming up the hillside to the tiny home at the top of the favela where I was renting a room. I was up on the roof that night talking with Bete, the daughter of the family with which I was living. Still in her early 2000s, Bete and her family was originally from the State of Pará, in Amazonia to the north. There leaning on an unfinished brick wall about waist-high, next to a clothesline hung with drying socks and underwear, she explained to me that the song was coming all the way from the Emoções Club at the bottom of the favela. Since the house in Rua Um, quite near the top, I couldn’t believe the music was coming from so far away: it was so loud! Maybe the enormous granite rock face of the Morro Dois Irmãos was somehow funneling the sound our way, I thought.

Since I had only arrived in Brazil for the very first time months earlier, my Portuguese was still quite rough. Indeed, it was more ‘Portuñol,’ as people often jokingly call the mixture of Spanish and Portuguese. Bete did her best to help me understand the meaning of the song. Though I was grateful for her efforts, I remember that the playfully sexualized tone of the song struck me as woefully vulgar and the singing unpolished. The cheap eroticism of the song was especially apparent in the one verse I could easily make out by myself, a gleeful cry of “…e a mulher abre as pernas!” (“…and the woman opens her legs!”). Bete didn’t seem phased by it at all. In fact, she told me that she originally had been planning to go to the dance party herself, but something had come up. When she told me that she’d go for sure the next week I had no desire to tag along and dropped the subject. That same year, a funk carioca song became a radio hit in Rio. “Feira de Acari,” produced and mixed by funk great DJ Marlboro and sung by MC Batata, was based on the famous stolen goods market in Acari, on Rio’s north side. Despite the fact it was one of the first-ever Brazilian funk songs sung in Portuguese, hearing the song did little to change my view. Though I found it mildly amusing, I incorrectly assumed “Feira de Acari” was merely a low-quality rip-off of hip-hop.21

With my limited initial contact with it that year, I had not yet understood funk carioca as constituting an important development in Brazilian music; even though it had already been playing an increasingly crucial role in the lives of poor young people over the previous decade or two. In truth, I somewhat loathed the music at first: funk carioca was cheap-sounding and superficial. It was not as ‘authentic’ as the Afro-Bahian Carnival music that was at the time emerging from the more explicitly consciousness-raising afoxés and blocos-afro like Filhos de Gandhy, Ilê Ayê and Olodum. As I returned to Rocinha several times—as a researcher, social activist, community educator and neighbor, eventually coming to live there for a total of over four years-over time I slowly gained an appreciation for the significance of the music in the lives of my young friends and neighbors. Eventually, funk carioca won me over as a fan: for the music and lyrics and for the utopian intensity of those colossal community dance parties in the streets of Rocinha.

In the mid-1990s, the style underwent its first major boom, suddenly rising to a previously unknown level of exposure in television and radio, not only within Rio, but throughout Brazil, and gaining a following that cut across social classes. Songs like MC Cidinho and Doca’s “Rap da Felicidade,” Leonardo and Júnior’s “Rap das Armas,” Willian and Duda’s “Rap do Borel” and Claudinho and Buchecha’s “Nosso Sonho” were instantly ubiquitous on radio and TV all across Brazil. I also became interested in the social and political concerns evident in the music, especially the consciousness-raising aspects regarding issues such as racial and class discrimination. Many songs from those early days also dealt with the theme of putting an end to the violent clashes occurring in the city’s funk dance halls that were occurring at the time outside of favelas (in the infamous bailes de corredor, names for the so-called ‘death corridors’ formed in such dance parties).

It was in the early 2000s that funk carioca entered into its second major boom, one in which the sub-genres putaria and proibidão became central. During the mid-1990s, despite the popularity of funk acts and the radio-friendly versions of some select songs, funk parties had been demonized in mainstream society to the point they were chased off from clubs and other venues of the formal city. This vilification coincided with an effort on the part of the legal authorities to quell the collective fighting in the death corridor-style bailes. As a result, the locus of funk culture moved from clubs in mostly low-income neighborhoods to the city’s favelas, where the community street dances assumed central stage (Herschmann 2000, 87-123). Such a shift placed Brazilian gangster rap at the center of the parties, too, along with the favela drug traffickers who commonly sponsored them. In those days, proibidão and putaria—usually identified as separate subgenres of funk today—were conflated, often under the name raps proibidos(‘forbidden raps’). Originally, this prohibited or forbidden style of funk arose as an underground expression, mostly from live performances at funk dances involving alternate versions of radio-friendly songs.22 Recordings of these songs emerged from clandestine studios to be distributed in the informal economy of favelas on cassette tapes and CDs to celebrate the names and deeds of local drug traffickers.

My status in those years as an on-and-off resident of Rocinha placed me in a position to witness firsthand these developments in that first boom of consciousness-raising-style funk in the mid-1990s and then the rise of the proibidão-style gangster rap of the second explosion in the popularity of the community dances. In the summer of 1996, I began formally studying funk, as a Ph.D. student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. As I delved more deeply into the subject over the years, in readings, lyrical and performance analyses and broader ethnography, two central questions emerged in my thinking.

The first was about how proibidão funk functioned as one of the principal arenas through which the power and legitimacy of Rio’s favela drug gangs were produced and lived. I didn’t see this process as merely a top-down ideological imposition by the drug traffickers upon the other residents. It struck me instead as a complex field of negotiations, in which residents also exerted a significant degree of influence upon their would-be leaders in the gangs, from the bottom-up.23

Beyond the issue of violence and crime, however, it seemed to me that an even more primordial theme of funk carioca was community—in the ‘live’ sense of a collective encounter. In this vein, the other primary question guiding my research was that of the Afro-Atlantic aesthetics of funk carioca. It struck me as a powerfully utopian musical practice born of the remarkably fluid hybridity of the favelas and the politics of transformation characteristic of African Diaspora peoples. For me, more than any other context of funk carioca the outdoor spaces of the bailes de comunidade embodied the counter-cultural utopian tendencies of Black Atlantic cultural expressions.24This focus on utopia also made it possible for me to begin comparing and contrasting funk carioca with other utopian popular cultural forms in Brazil such as Carnival, capoeira, Brazilian hip-hop and even the country’s more literary modernismo. I also wondered to what degree these two questions intersected. In other words, how did the negotiation of power in the favela in ideological terms relate to the Afro-Atlantic aesthetics of the music?

With such considerations in mind, in Chapter Two of this book, “Machine Gun Voices,” I explain in greater depth the motives that led me to study funk in Rio in the first place and offer a bit of my personal history in the favela of Rocinha. I also offer a summary of trends in Brazilian music at the time of the golden age of proibidão funk in the community dances and discuss the emergence of that style in regards to those trends. In Chapter Three, “Writing about Funk Carioca,” I discuss several of the major studies of funk that were influential on my fieldwork and comment on the methodological procedures I employed in carrying it out. In Chapter Four, “Proibidão and Rio’s Gangs,” I present my discussion of proibidão funk in the context of the aftermath of the murder of investigative journalist Tim Lopes in 2002 and the debates regarding the culture of drug trafficking. In particular, I attempt to bring the discussion on crime and security in Rio beyond the mostly economic focus of Alba Zaluar, a well-known specialist on crime in Rio, to open up consideration of the more cultural side of hegemony in that context.

Chapter Five, “Rocinha Favela,” provides a brief social history of Rocinha and offers a reading of the baile funk in the streets of the favela as a staging of their power. With Chapter Six “Crimes of Self Defense,” my goal is to consider in greater detail the specific ideological strategies evident in proibidão and the ways those strategies have served in the negotiation of an image of the drug traffickers of the favelas of Rio de Janeiro as “social bandits.” In Chapter Seven, “Social Bandits in Funk,” I discuss the portrayal of organized crime in funk in songs like “10 mandamentos da favela” (“10 Commandments of the Favela”) as comparable to the notion of the social bandit developed by E. J. Hobsbawm. Chapter Eight, “Bandits of Christ,” further explores the figure of the proibidão MC as a mediator of the culture of crime in Rio’s favelas, between actual gangsters and their cartels and the everyday, non-gangster residents in and around favela community funk dances parties. I expand upon this in Chapter Nine, “Trafficking Culture,” undertaking additional close readings of proibidão lyrics to analyze the ideological strategies of the drug gangs evident in them, according to ideological categories suggested by Terry Eagleton.

In the tenth chapter, “Musical Survival Tactics,” I move from the question of violence and organized crime in funk and favelas to an exploration of its Afro-Atlantic aesthetic dimensions as a utopian cultural practice. In Chapter Eleven, “Utopias de Favela,” I follow the straightforward analytic framework employed by cultural critic Richard Dyer in his influential article “Utopia and Entertainment.” In the next chapter, “Mixes from the Margins,” I examine the baile funk as an example of the utopian community practices of the cultures of the African Diaspora, analyzing it considering what Paul Gilroy has referred to as the “politics of transformation.” I consider the tendency of funk carioca towards hybridity through the lens of Brazil’s famous cultural cannibalism aesthetics and beyond, as well as comparing it to expressions of Carnival and hip-hop in Brazil. In the final chapter, “Last Dance,” I reflect on the connections between the threads of violence, utopianism and community dealt within throughout the various chapters and contemplate the significance of funk in the context of the struggle for social justice in Afro-Atlantic culture today.

To bring this study of Brazilian funk full circle, from my original observations during the time of my original fieldwork to today, I have included an Afterword reflecting back upon that golden age of funk carioca in Rocinha from my point of view today. In the interval, much has changed in Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro and Brazil, not least of all funk itself and the academic scholarship on the subject. Despite changes in the music and Rio’s favelas over time, however, the representation of the power of the drug traffickers that arose in the late 1990s and early 2000s in funk continues to be central to everyday life in communities like Rocinha. Similarly, the utopian dimensions of the live outdoor community street dances continue to attract a new generation of funk fans and artists and to offer them a mode of relational collective resistance. Looking back at that pivotal time now indeed offers relevant vistas into the ongoing crisis of social exclusion and violence persisting in Brazil to this day.

In 2003, when I first defended that early dissertation form of this study, I was reluctant to publish my findings in book form. I worried that a book titled Machine Gun Voices might contribute to the bad reputation of Rocinha and other much-maligned favelas in Rio and throughout Brazil. As the years have gone by, I have seen how the work is relevant not only as local case study of violence and community and for its broader implications for social justice in the context of the Afro-Atlantic world. From my point of view now, the utopian aspects of funk carioca point towards an even more profound, more primordial impulse at play in the live street funk parties rooted in our pan-human needs for relationship and attachment. In a sense, I see a progression in my own thinking from the two central concerns of my original work in the 2000s—in the culture of crime and the utopianism of funk—to a Community Studies perspective.

Viewing funk in this way seems especially important to me from my current vantage point living and working here in Korea, a country that is grappling with violence and dehumanizing polarization in its own right. Internally, recent years in Korea have seen the Candlelight Revolution and the ouster of President Park Geun-hye for corruption. Externally, the threat of nuclear war in the region looms larger than ever. In the face of such challenges, like in the case of Brazil and the favelas of Rio de Janeiro there is hope here in Korea, too. The 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics attest to this, as efforts for cooperation and dialogue between the Koreas intensify.

In this light, I could say that, although the title of that original work has not changed its meaning for me has. At the very least it has expanded. The “machine gun voices” in question are not merely a defining feature in the soundscape of the often brutal reality of Rio’s favelas or even echoes of the gangsters’ gunfire, as such. For the favela residents, those machine guns and the sounds they make are their own, both as emblems of the difficulties they face in the conditions of their lives and as symbols of their determination to forge a community and protect it through their own travail. In the sense that funk carioca is part of something larger than Brazilian culture or even the Afro-Atlantic world, for me, those machine gun voices of funk are also a symbol of the universal suffering of human beings everywhere as we hold on together for the possibility of some more profound peace and coexistence.

1This description of a baile funk is offered both as one of an actual event occurring on February 8, 2002, and as a synthesis of other community dance parties taking place in Rocinha over the years of my residence there as a researcher, neighbor and community educator from the US.

2At the time of my early fieldwork in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the criminal faction known as the Comando Vermelho (‘Red Command’), or CV, operated in Rocinha. During subsequent fieldwork in 2004, the faction called Amigos dos Amigos (‘Friends of the Friends’), or ADA, gained control. In November 2011 the government intervened with a community policing program called Unidades de Polícia Pacificadora, known as UPPs, or Pacifying Police Units. Despite some initial success, the program floundered and in September 2017 a major turf war erupted in Rocinha. At the time of writing (May 2018), friends living there report that, after initial infighting between rivals from within the ADA, the larger CV has been making a move to return to the favela. As of May 18, 2018, residents in personal correspondence with the author report that members of both the CV and ADA are in the favela, controlling different areas, along with a permanent police presence. The UPP is scheduled to be closed, along with roughly half the UPPs in the favela locations in Rio, and replaced with more conventional battalion not geared towards community policing (O Globo, “Intervenção”). According to news reports, as of January 2018, the related deaths of 37 persons occurred in Rocinha since September (G1, “Desde setembro”). Sporadic confrontations continue and just days ago a much-loved seventy-five-year-old man named Francisco Nunes da França, known in the community as Ciclista Pipoca (‘Popcorn Cyclist’), died victim of a stray bullet (Extra Online, “Tiroteio” and UOL Notícias, “Morador”).

3For a short recapitulation of the recent history of the Rocinha drug gang since the golden age of Brazilian gangster rap in Rio’s favelas analyzed throughout this book, see Glenny, “One of Rio de Janeiro’s Safest Favelas Descends into Violence.” For a more detailed account, see Nemesis (Glenny 2015).

4Bin Laden was a popular figure in the gangs at the time, which was shortly after the 9/11 Attacks.

5For perspective on the urgency of such ongoing violence in this context, 2017 Rio recorded 6,590 violent deaths, the highest number in a decade. There were a staggering 61,000 total violent deaths across Brazil during the same time (Faiola and Kaiser, “A Once Trendy Slum”).

6Schmidt, “Estudo aponta mais 49 favelas,” also cites the 2000 census conducted by the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) estimating the population of Rocinha at 56,000. In my interview on July 3, 2009 with Wallace Pereira da Silva, then president of the Associação de Moradores e Amigos do Bairro de Barcelos (AMABB, one of three neighbor’s associations in the favela), he estimated the unofficial population at around 160,000. That same year, employees of the governmental XXVII Centro Administrativo da Rocinha, a branch of the City Hall, told me it was 120,000. When I first went to Rocinha in 1990, I became friends with the president of another of Rocinha’s neighbor’s associations, União Pró-Melhoramentos dos Moradores da Rocinha (UPMMR). Seu Pereira (Everindo da Silva Pereira), who has since passed away, helped me much with my initial research on organized crime in the favela. He told me that there were 300,000 people in the neighborhood. With such a tendency to inflate numbers, Rocinha’s fabled size has become a part of itsambivalent mystique and, consequently, some may be disappointed to hear there are perhaps fewer residents than was previously thought. In any case, the difficulty in assessing the size of the population in of itself is evidence of Rocinha’s nature as a partially informal community.

7The official number of favelas recognized by City Hall in Rio de Janeiro went up in 2003 from 603 to 752 (Schmidt, “Estudo aponta mais 49 favelas”). Note that this excludes favelas from Rio’s surrounding suburbs.

8Whatever the number of people is, the relatively small physical space it occupies makes it quite densely populated. According to The Economist, “Rio’s Post-Olympic Blues,” the total area of Rocinha is 1km2 with a population of roughly 100,000. Also see Bernardo Tabak, “Maior favela do país.”

9Charlys da Rocinha continues to embody such a spirit of favela versatility to the present day, most recently as a singer of Brazilian Contemporary Christian Music. Charlys, his brothers Carlos and Alan and our friend Renato Moreno helped me immeasurably with my research over the years. MCs Leonardo and Júnior were also indispensable. MC Galo and MC Dollores were also supportive, as were countless other people associated with Rocinha’s funk scene throughout (see acknowledgments).

10For a thorough overview of reggaetón and its connections to hip-hop and other expressions of Afro-Atlantic youth cultures, see Reggaeton (Rivera et al 2009).

11More often than not, Brazilians simply refer to funk carioca as ‘funk.’ To avoid confusion with the American musical style of the same name, sometimes the word ‘carioca’ is added, especially by journalists, music critics, scholars and activists. Besides those names and ‘movimento funk,’ as people often called it in the mid-1990s, people use other names like pancadão, (literally a ‘big punch’ or ‘blow’) batidão (‘big beat’). In English, it’s often called baile funk, which in Portuguese actually refers to the massive dance parties in which this music is played, and sometimes favela funk or Rio funk. For more nuanced and expansive list of names for funk and its subgenres, see Batidão: Uma história do funk (Essinger 2005, 11).

12 For the early history of funk carioca, see O mundo funk carioca (Vianna 1988), O funk e o hip-hop entram em cena (Herschmann 2000, 18-31), and Abalando os anos90, (Herschmann 1997, 7-13), and Batidão (Essinger 2015) (for his exploration of Rio’s Black Pride scene see his chapter “Em tempos de soul power,” 15-48).

13For the evolution of the musical characteristics of funk carioca, including its beats from the volt mix sound of the mid-1990s to the tamborzão style (‘big drum’) of the early 2000s and the ‘beat box’ sound of the 2010s—and the way these changes connected historically to developments in Brazilian politics and society—see Caceres, Ferrari and Palombini, “A era Lula/tamborzão.”

14The perfect pitch of the duo on the track is remarkable, as well, especially in the artfully crafted list of favelas and other working-class neighborhoods in its middle section. Like most songs mentioned in this book, “Nosso sonho” is readily available on YouTube.

15For more on putaria, especially the debates as to whether or not the female MCs should be considered organic feminists, see Caetano, “My pussy é o poder: representação feminina através do funk: identidade, feminismo e indústria cultural,” Moreira, “Bitches Unleashed.”and Funk-se quem quiser (Lopes 2011, 151-210).

16 For more on funk de raiz and funk activism more generally, also see Funk-se quem quiser (Lopes 2011, 67-150). As the most in-depth study to date of funk carioca’s role in leftist mobilization in Rio, her narrative provides detailed accounts of the partnerships between funkeiros, journalists, university professors, politicians and other activists in promoting funk and social inclusion more generally. See especially chapter three, “De funk de raiz a movimento político e cultural,” 99-150.

17 My efforts to track down the acclaimed funk documentaries—not including feature pieces in news media—have turned up nearly a dozen (all listed in the bibliography). Also relevant are commercial productions prominently featuring funk dances, such as the Oscar-nominated feature film Cidade de Deus (2002), José Padilha’s Tropa de elite (2007), Vai Anitta (2018) and the television episode “Sábado,” from the series Cidade dos homens (from Fernando Meirelles, one of the directors of Cidade de Deus). In my opinion, this last production offers a particularly poignant portrayal of the bailes funk for its focus on the experience of everyday fans, along with Funk Rio, mentioned above. The latest is 2018’s Vai Anitta, a six-part docu-series from Netflix about the funk singer turned Brazilian national diva Anitta.

18 Of particular relevance to my view in this sense is Gilroy’s treatment of musical expressions in Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness (Gilroy 1993), especially chapter 3, “Jewels Brought from Bondage: Black Music and the Politics of Authenticity,” 72-110.

19 With the idea of ‘limbic realism’ in this context, I am thinking of work done in the field of psychology emphasizing such neuro-physiological interdependencies, as expounded by Flores, Addiction as Attachment Disorder. An earlier, even more foundational work in this vein is Thomas Lewis, Fari Amini and Richard Lannon, A General Theory of Love, in which the authors provide a concise summary of the nature of such limbic inter-connectedness. I consider this more closely in the Afterword.

20See especially Funk-se quem quiser (Lopes 2011, 68-74), “No dia em que o parlamento cantou…”

21