22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Over the centuries, the corset has been a vital garment designed to support and shape the fashions of the day, and has progressed from being an undergarment to bold outerwear. This practical book explains the full process of making a corset with clear instruction and supporting photographs. Packed with information, it explores methods of creating modern corsets, whilst acknowledging the pioneering techniques of the past. Whatever your reason for creating a corset- be it for theatre- re-enactment or personal wear - this book is an invaluable guide to making a well-constructed, figure-flattering garment. Includes: a list of helpful tools, equipment and materials; step-by-step illustrated instructions showing how to self-draft or personalize a commercially purchased corset pattern; techniques showing how to correct an array of fitting issues to produce a well-shaped corset; a selection of corset-making methods, illustrated with photographs and, finally, imaginative approaches to decorating and personalizing corsets. There are three main projects showing the development of the patterns and construction techniques to create gorgeous corsets.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 313

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

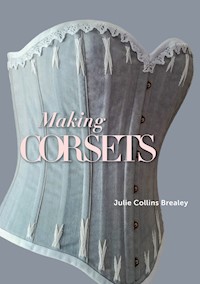

Making

CORSETS

Lady in a Red Corset, artist unknown, oil on canvas, from the PCF Fine Art Collection. (Reproduced with permission of Leicestershire County Council Museums Service)

Making

CORSETS

Julie Collins Brealey

First published in 2021by The Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2021

© Julie Collins Brealey 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 821 4

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the memory of my wonderfulMum and Dad, Dora and Keith. I know you would be proud.

Contents

Introduction

1

A Brief History of the Corset

2

Tools and Equipment

3

Materials for Your Corset

Corset Hardware

Fabrics, Textiles and Haberdashery

4

Measuring the Body

5

The Corset Pattern

6

The Toile

Making Your Toile

Fitting the Toile

Further Fitting Solutions

7

Creating Your Corset

8

Corset Construction

9

Grey Coutil Overbust Corset

10

Floral Silk Underbust Corset

11

Green Taffeta Overbust Corset

12

Alternative Corset-Making Techniques

13

Personalizing Your Corset

Conclusion

Glossary

Useful Information

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Index

Introduction

I have been teaching corset making now for a number of years, so when I was approached to write this book I felt that this was a great opportunity to pass on my experience and skills in detailing the process. I believe you will derive the same sense of satisfaction, achievement and pride in making a corset as I do.

On writing this book, my intention was to attempt to make the art of creating a corset accessible to all skill levels, whether you have some experience with sewing and using patterns or whether you are a complete beginner. Whatever your degree of knowledge in the subject, this book should offer technical guidance and new ideas and tips for you to work with. If you are an experienced corset maker, you may find a few useful methods and suggestions to add to your collection.

Floral silk underbust corset.

Your reason for making a corset is entirely personal. The satisfaction of seeing the garment come to life, with its two-dimensional panels transforming into the curving shapes of the three-dimensional piece, is magical. This is reward enough. Then, achieving the flattering fit which enhances the shape of the body is gratifying. Finally, progressing onto the finishes and embellishments to complete your unique creation is truly an achievement. However, the purpose of the corset may be solely because of the feeling that this body-hugging garment offers. The support, the way that it shapes the body – these are enough for many people to want to create their own corset.

Maybe there are other reasons: your goal may be historically accurate corsets or those made for reenactment – you may wish to construct these using techniques and materials as authentic as possible, performing much of the stitching by hand or by a vintage hand-operated sewing machine. Alternatively, your corset may be destined for use on the stage, in costume drama or burlesque, or for fetish wear. Whatever the purpose, you will want your corset to be the best that it can be – well-constructed, with a good fit and plenty of support.

If the corset fits well and supports the body effectively, it should not cause any undue pain or damage. Contrary to popular belief, a corset is not necessarily detrimental to a person’s health. However, over the centuries, experiments with the fashionable shaping of the day have caused some discomforts. Generally, though, a well-fitting corset should be quite comfortable. Furthermore, the support that a corset offers is usually beneficial to the posture and to any minor back problems. If you wish to tight-lace your corset, try to do this gradually: you will find that extreme tight lacing will be uncomfortable otherwise.

With this book, my intention is to lead you through the creation of a corset, from the initial inspiration and design through to the beautifully finished result.

Throughout this journey, we will explore the materials and tools used to make your corset. We will then look at what constitutes a ‘good fit’, before moving on to accurately measuring the body to try to achieve this. There is a comprehensive chapter detailing the corset pattern, where we will explore the advantages of both the self-drafted and the commercially available pattern. I will demonstrate, through clear step-by-step instructions, the processes of adjusting the commercial pattern to fit and of self-drafting a pattern to your own body measurements. This will lead on to the construction of a temporary mock-up garment, a ‘toile’, which will enable you to perfect the fit, before moving on to a selection of corset-making techniques which you will apply to your corset.

In this book, there are three corset projects for you to follow. These are designed for the female figure but all the information on fitting and construction is translatable to corset making for the male shape.

The three projects demonstrate the creation of two overbust corsets and one underbust corset. These are all based on a traditional Victorian hourglass shape, which would have featured ten or twelve panels. Each project illustrates techniques of styling the corset and adjusting your original pattern to achieve this design. Methods relevant to constructing the corset are detailed, including some alternatives for you to try. Towards the end of the book there are suggestions of ways that you can customize your corset by adding decorations, embellishments and so on. Techniques in this book are supported with detailed step-by-step instructions and photographs, carefully leading you through each process.

The status of the corset has progressed from its original function as an item of underclothing. Who would have thought that this fascinating little garment, which has seen so many changes through the centuries, would now be regarded as a fashion statement and worn as outerwear?

This progression is shown at the beginning of the book where I have included a concise chapter on the history of the corset, introducing the garment and exploring its development, both its changing shape in fashion and its function, through the ages.

Though I will not be demonstrating historical corset construction techniques in this book, I do appreciate the exploration and research that went into achieving the most effective practices. The groundwork was done, and our modern methods are merely fine-tuned versions of these processes.

I will, however, be drawing comparisons between old and modern methods and materials, and the development from one to the other. I will be detailing alternative techniques to offer different options when working on your projects.

Whichever methods you choose for assembling your corset, it is necessary for the garment to be sturdy and well assembled. The corset is unlike any other garment that you will have made before in that its dimensions are smaller than your body measurements (this is called ‘negative ease’). Because of this, the corset, when worn, is subjected to much stress, especially on seams, lacings and so on, so it is very important to use suitable materials and construction techniques to add longevity to the garment. It would be a great pity to have spent many hours in the assembly of the corset only to find that it falls apart after having been worn only a few times.

Enjoy learning this fascinating skill of corset making. The information that this book offers is just a small percentage of the material available on this subject: it can be complemented by further research from books, exhibitions and websites.

Back detail of green taffeta overbust corset.

CHAPTER 1

A Brief History of the Corset

Through the centuries, variations of the corset have been worn to alter body shape and conform to the fashionable silhouette of the day.

As far back as 1600 BCE, there is evidence of a primitive form of corset which was worn by the Minoan people of Crete: ancient pottery figures depict the body tightly bound with firm fabric or leather. Since then, the shape and function of the corset have evolved dramatically.

From the fifteenth century, garments stiffened with paste were worn. Designed to compress the body and flatten the breasts, they were laced at the front and strengthened with strips of bone and wood.

This trend continued through the sixteenth century, where the natural roundness of the body was compressed into the new, fashionable conical shape. The silhouette was shaped as an inverted cone with a long, pointed bodice giving a slim, tightly bound appearance. It was expected that all wealthy women should wear corsets. These corsets were laced at the front, back or sides and included shoulder straps. They constricted the body, giving a flat-fronted look which pushed the breasts upwards, revealing the curve of the top of the breasts above the corset. At that time, corsets were referred to as ‘a pair of bodies’.

Black corset from the Symington Collection, dated 1895, featuring a spoon busk, flexible cording over the hips and machine-stitched feather embroidery flossing. The corset is boned with over forty cane strips and steel bones support the back panels. (Reproduced with permission of Leicestershire County Council Museums Service)

The busk was invented during the sixteenth century, as a means of stiffening the front of a corset and forcing it to lie flat. This would have been a rigid strip of wood, bone or iron which was inserted into a casing on the corset front.

Corsets of the seventeenth century were designed to accentuate the bust and neck area. The top edges were trimmed with lace to highlight these features. As this century progressed, corsets started to include more boning, in the form of reeds and whalebone (baleen). The long pointed busk had now become more decorative, with carvings and engravings, and could be made with ivory or silver, as well as bone and wood as before. The front lacings of the corset were covered by a V-shaped ‘stomacher’ which was made from a highly decorated cloth, and the lower corset edge was slashed to form tabs which helped the garment to fit round and below the waist. The popularity of the corset increased, which meant that men and children also wore them. The ‘pair of bodies’ were now referred to as ‘stays’.

During the eighteenth century, corsets were very constricting. Supported with whalebone or cane, the corset created a very small, low waist and narrow back, whilst pushing up the bust, still giving the conical appearance. The wide shoulder straps would be pulled together across the back, until the shoulder blades met. The corsets (stays) were laced across the front or back using the spiral lacing method. (We will be looking at corset-lacing methods in Chapter 12.) Corsets incorporated the tabs, as before, which opened out to allow more room over the hips.

As waistlines became higher and the Empire line was introduced at the beginning of the nineteenth century, corsets became shorter. They were now more lightweight with minimal boning, and featured cups to support the breasts and a busk to separate the cups. Breasts were accentuated and, as flowing garments were now fashionable, there was no need for the tight compression of earlier styles.

Fig. 1.1 Timeline of corset shapes through the centuries, showing the changing position of the waistline in fashions.

Around mid-century, the waistline dropped again and the hour-glass silhouette was on trend. The corset was still reasonably short, finishing just below the waistline, stiffened with whalebone and tight-laced to minimize the waist. Around this time, gestational stays became available which incorporated adjustable gussets on the front and bust areas to allow for expansion during pregnancy.

The nineteenth century welcomed the invention of the front-opening busk which was a revelation as a woman could now dress unaided. Also, just prior to this invention, metal eyelets were invented. These replaced the hand-stitched eyelets and would prove to be much stronger and prolong the life of the corset. Now, because the corset could be opened at the front, a different method of lacing emerged. The ‘rabbit ears’ method incorporated cross-over lacing with loops that could be tightened by the wearer. This meant that the corset did not need to be completely unlaced during undressing and dressing. Merely loosening the laces was enough to be able to unfasten the busk and remove the corset from the body.

This century welcomed other innovations in the field of corsetry. New types of ‘breathable’ fabrics were introduced in order to make corsets more comfortable. Summer corsets were designed with mesh inserts, some incorporating eyelets round the waist, for ventilation.

When fashions changed again later in the century, corsets became longer and more curvaceous, fitting snugly round the hips. They were now strengthened using steel or cane, with the newly invented spoon busk supporting the front. This shaped busk compressed the front of the body inwards at the stomach, curved outwards round the belly and again inwards underneath the belly. It was later realized that this design of busk was detrimental to the health as it caused too much compression and damage to the internal organs.

During the latter part of this century, men’s corsets became more fashionable. In earlier times, it was not unusual for a man to wear a corset to achieve a sleek silhouette, but now men’s corsetry was more widely available.

The very early years of the twentieth century saw the introduction of the S-bend or swan bill corset. This was tight-laced and straight-fronted, resulting in a very upright posture with a low, sloping bust, small waist, flattened belly and greatly exaggerated hips and buttocks. The busk was again straight, as this was deemed to be a ‘healthier’ option, but it was also very long. This was intended to push the pelvis and hips backwards, giving the body an unnatural S-bend shape. This was a ‘midbust’ corset where the top edge had lowered to nipple height, and designs were very long, ending around the mid-thigh. Suspenders were introduced, comprising long elastic strips with clips designed to hold up the stockings. The S-bend was a particularly uncomfortable fashion and so endured for less than ten years. Indeed, corsets themselves seemed to be on the decline. Some loose-fitting garments introduced before the First World War allowed women to go without corsets.

However, the corsets that were still around were constructed with elastic inserts. This resulted in a far more comfortable undergarment and allowed more mobility, as many corset designs of that time ended well down the thigh.

During the 1920s, a boyish silhouette was fashionable so the body shape needed to become slimmer. The corset was replaced by the girdle, a narrower and more elastic garment, with minimal boning, which enabled the hips and belly to be controlled. The girdle would be worn with a separate bra.

Fig. 1.2 Detail of an 1895 corset from the Symington Collection, featuring flossing and lace trimming. (Reproduced with permission of Leicestershire County Council Museums Service)

The silhouette of the 1930s and 1940s was still slim but with the emphasis on a small waist. Many corsets of this time were constructed with a built-in bra. Elastane, a new elasticated fibre, was incorporated into some fabrics, making the corsets more comfortable and easier to put on.

Christian Dior’s ‘New Look’ in 1947 brought the hour-glass figure back into fashion, which resurrected the full corset for a while as this style warranted a very small waist and accentuated hips.

In the 1950s, the all-in-one ‘corselette’, which was a combination of girdle and bra, featured pointed bra cups stiffened with circular stitching to force the breasts into a conical shape. This look would be revived by Jean Paul Gaultier in 1990 for Madonna to wear on tour.

The 1970s, with the arrival of the punk movement, brought the corset to the fore as an outer garment. Up until then corsets were intended to be worn as underwear, but now innovative fashion designers such as Vivienne Westwood and Gaultier were injecting new life into the garment.

The corset, now mainly worn as outerwear, continues to develop and grow in popularity, and is featured regularly in the ‘big four’ fashion week runway shows. The iconic corsetier Mr Pearl keeps this garment in the forefront of fashion by designing corsets for the likes of Thierry Mugler and Alexander McQueen. These are often gloriously showcased by the ‘Queen of Burlesque’, Dita Von Teese.

Today, there are numerous reasons for a woman to want to wear a corset. Many are worn for aesthetic reasons, to emphasize and enhance the body shape, accentuating the bust and hips and the smallness of the waist, and promoting a feeling of sensuality and desirability. Waist training, an extreme form of tight lacing over a period of time, can change the body shape. This may be too extreme for some, who just like the support and ‘body-hug’ that the corset offers.

Wearing a corset can help correct the posture and aid with other medical issues. It will support and protect an injured body or one with spinal problems.

Some may wear a corset in a theatrical setting as part of a costume, or in a burlesque show. Others like corsets as fetish or fantasy wear.

The steampunk movement features the corset as one of its main items of costume, combining this with other Victorian-style garments and adding leather, metal and industrial-looking accessories.

Mainly, corsets worn these days will be of the tenor twelve-panel Victorian shape, with a front-opening busk and back lacing. This hour-glass silhouette seems to be the most desirable. A corset can be incorporated into a wedding dress or special-occasion outfit, resulting in a figure-flattering shape without the need of a supporting undergarment.

As well as the Victorian corset, there are also commercial patterns currently available for most historical styles of corset which could be worn for theatrical purposes, re-enactments, historical gatherings and cosplay.

In acknowledging and appreciating these reasons for wearing a corset, I am convinced that this versatile garment will be around for many more years to come.

Mass-Produced Corsets

With the invention of the sewing machine, mass production of the corset was introduced in the mid-nineteenth century. The demand for a good-quality, reasonably priced corset was at a peak, so corset factories were established in order to meet this demand. Symington & Company, based in Market Harborough, Leicestershire, were one of the first mechanized corset factories. They were a main manufacturer of mass-produced corsets, becoming internationally renowned, exporting their corsets to Australia, Africa, Canada and the USA. Fig. 1.2 shows detail of a beautiful Symington corset from 1895, where you can see the intricate machine-stitched flossing design, ribbon-threaded lace and embroidered trim.

CHAPTER 2

Tools and Equipment

In this chapter you can see a selection of the tools and equipment widely available for corset making, each with a brief description. You will not need to acquire everything on the list. Some of the items I will use during the corset-making process, and some are shown as alternatives. Read this book before you decide which items you need. You may already have some of the items in your sewing kit. Many are readily available and inexpensive. More details on how to use these tools will be included in further chapters.

If you are new to corset making, I suggest that you purchase pre-cut boning so that you will not need to buy the bone-cutting equipment. Pre-cut boning is more expensive than cutting and tipping bones yourself, but good-quality tools can be quite pricey so wait until you are sure that you need them before purchasing. Buy the best that you can afford. It is false economy to buy cheaper, flimsy tools which will not do the job properly and will almost certainly break.

Selection of tools and equipment used to make the corset projects in this book.

Note that I have included brand names of the items which I use frequently. In all cases there will be comparable products on the market – just read specifications carefully and test on scrap fabrics before using on a major project.

Sewing Equipment

A basic sewing machine is adequate for corset making as almost all that is required to make a corset is a straight stitch. However, the machine does need to be sturdy as it will need to cope with multiple layers of tough fabric. Most machines will have a stitching guide engraved into the needle plate, as shown in Fig. 2.1: this will enable you to keep to a regular and accurate seam width. Check the width of seam allowance by stitching on a scrap of fabric first.

Fig. 2.1 Needle plate on a sewing machine, showing engraved stitching guides to ensure accurate seam lines.

Use good-quality sewing machine needles of medium to heavy weight, depending on the thickness of fabric and the number of layers to be stitched. Change the needles regularly to prevent the fabric from snagging.

Most of the machine stitching on your corset can be carried out with an all-purpose presser foot.

Fig. 2.2 Presser feet for corset making. L to R: all-purpose foot; Teflon foot; zip foot; open-toe foot.

Alternatively, a Teflon foot can be used which helps the fabric glide more easily over the needle plate. You will need a zip foot for inserting the busk into your corset. An open-toe foot is also useful when stitching boning channels, although this is not essential. Fig. 2.2 shows examples of these feet. Note: the zip foot is double-sided to enable you to stitch down either side of the busk; however, a single zip foot will produce the same result if adjusted carefully for each side.

All-purpose polyester sewing threads work well with any fabric, no matter the fibre content. Buy a good-quality thread: cheaper ones can tangle in the machine tension and snap. If you are planning to floss the ends of the boning channels, use a buttonhole twist or silk thread. (See‘Flossing’ in Chapter 13.)

Fig. 2.3 A seam ripper, or unpicker, is useful for ripping out whole seams or individual stitches; it is seen here with safety pins that have a multitude of uses.

The seam ripper or unpicker, as shown in Fig. 2.3, has a very sharp, pointed blade which is useful for ripping out any seams that have been incorrectly stitched or need to be let out, particularly when adjusting the toile. Small, sharp scissors can be used as an alternative. It is seen here with safety pins, which have a multitude of uses.

Use good-quality, fine hand-sewing needles in a variety of sizes and lengths to suit the weight of fabric that you are working with. Don’t be tempted to use chunky needles just because they are easier to thread, as they will make it more difficult to penetrate the fabric. Use embroidery needles for flossing: these have a larger eye to accommodate the thicker embroidery thread.

Using beeswax on hand-sewing threads will minimize the chance of the threads knotting and help threads to pull through the fabric more easily.

Fig. 2.4 Good-quality hand-sewing needles, with beeswax used for lubricating thread during hand-stitching.

Fig. 2.4 shows a packet of good-quality needles for hand-sewing and a container with beeswax. Run the thread through one of the slots round the edge of the container to keep the thread lubricated.

Fig. 2.5 Various types of thimble and finger shield are available to protect your fingers when hand-sewing through thick layers of corset fabric.

It is advisable to use a thimble or finger shield when hand-stitching through several layers of fabric, especially coutil, to protect the fingertips. Various types are available, as shown in Fig. 2.5, so choose one that is comfortable.

Dressmaker’s pins are handy for holding fabric in place whilst hand- or machine-stitching. Note: never machine-stitch over pins – remove each one before it gets close to the presser foot. Buy good-quality pins which will not rust or bend. I recommend Prym dressmaker’s pins which come in lots of different lengths and thicknesses. A pincushion is a safe and convenient place to keep your pins, and is easy to make too, using scraps of fabric.

Fig. 2.6 Pins and Wonder Clips are multi-functional and are useful for holding corset components together during stitching.

Wonder Clips are marvellous little pegs that can be used for many projects. They grip tightly, holding fabrics, trims and so on in place whilst sewing. The bottom surface is flat so these little clips can be used with a sewing machine, instead of pins, to aid stitching. They are great for attaching elastic. Fig. 2.6 shows a tub of Prym dressmaker’s pins with a pincushion and a selection of Clover Wonder Clips.

Cutting Tools

Fig. 2.7 shows a variety of cutting equipment needed for corset making.

Fig. 2.7 Cutting equipment for corset making. L to R: fabric shears, rotary cutter, small thread-cutting scissors, thread snips and paper scissors, all resting on a cutting mat.

You will need various pairs of scissors during the corset-making process: a good sharp pair of dressmaking shears to cut the fabric, a pair of regular scissors to cut paper, and a small sharp pair for trimming threads. Make sure that the dressmaking shears are kept solely for the purpose of cutting fabric – using them to cut paper will soon dull the blades.

Thread snips can be used in place of small scissors and are used to trim off thread-ends after stitching.

A rotary cutter is an alternative to scissors and can be used for cutting out your corset panels. The blade is very sharp, so extra care must be taken when using it; it has a protective shield which needs to be moved over the blade when not in use. If you prefer this method of cutting, the rotary cutter should be accompanied by a self-healing mat.

Self-healing mats come in various sizes and are used to protect the table from the cutting blade. The scratches on the surface of the mat close over after being in contact with the blade.

Measuring Equipment

Fig. 2.8 shows a selection of measuring tools used for corset making.

Fig. 2.8 Measuring tools used for corset making, including rulers, tape measure, pattern maker and protractor.

Buy a good-quality tape measure made from fibreglass with metal ends. A tape measure will often show metric measurements on one side of the tape and imperial on the other. Check the condition of your tape measure from time to time as it will need to be replaced if it is damaged or has stretched.

I prefer a see-through plastic ruler which can be used with a rotary cutter. Even more convenient is a flexible ruler used for measuring round curves. A small marking guide is a convenient extra. I recommend the Prym hand gauge which has metric markings and notches at 1cm intervals. It is very flexible and is great for measuring round tight curves. It also has the bonus of a little set square cut into the end of it.

A pattern maker or set square is a must for drafting patterns. I recommend the original Patternmaster® (by Morplan) which is made from sturdy perspex, although cheaper, more lightweight versions are available. The pattern maker combines a set square and ruler with a French curve, and incorporates parallel lines, pivot points and more. It is worth investing in a good quality piece, as it will last for years. They are available with metric or imperial measurements. As an alternative to the pattern maker, you could use a separate set square, ruler and French curve.

You may find that a protractor is incorporated into your ruler or set square. If not, a small, inexpensive protractor is adequate to measure angles.

Drawing/Drafting Equipment

Use a light- to mediumweight pattern paper for your patterns. Dot-and-cross or squared paper is easier to use, but plain paper is fine as long as you ensure that your right angles are drawn accurately.

Using the right pencil to draw fine lines is crucial in pattern drafting as a chunky line will result in a discrepancy in the size of the pattern. Therefore, use nothing softer than an HB pencil and sharpen it regularly. A propelling pencil is a good choice, as this will give a consistently fine line.

Fig. 2.9 Selection of marker pens for use on patterns and fabric.

There are many types of marker pens that you can use on your patterns and fabric. Fig. 2.9 shows a selection. For patterns, any type will work, although indelible markers are not advisable in case any of the ink strays onto your fabric. There are water-soluble and also air-erasable markers available for use on fabric. Either is fine, but make sure you test on a scrap of your fabric first, to make sure that the ink does disappear. I prefer to use Pilot Frixion ball pens which come in a variety of colours and can be used on paper and fabric. They give a fine line, which is crucial for accuracy, and can be erased from paper by friction and from fabric by ironing. Again, test on your fabric first.

Fig. 2.10 French curves are useful for pattern drafting.

In pattern drafting, French curves of varying shapes and sizes, as shown in Fig. 2.10, are useful and can be obtained inexpensively.

Scotch Tape, sometimes called invisible tape, is a useful alternative to sticky tape in your corset-making toolkit, as it can be drawn on with pencil or pen, and will not leave marks when peeled off fabric. (Comparable brands are available but read the specifications very carefully and test on scrap fabrics.)

Fig. 2.11 A pin tracing wheel or double tracing wheel can be used with dressmaker’s carbon paper to transfer markings from pattern to fabric.

There are various types of tracing wheels on the market. A smooth tracing wheel is suitable for delicate fabrics, whilst a serrated wheel works better on medium to heavier fabrics. A pin-wheel is more suited to pattern drafting as it is able to penetrate thicker layers of fabric, paper and card. A double tracing wheel can mark two parallel lines simultaneously and has removable wheels which can be spaced at 5mm increments. All tracing wheels can be used to transfer pattern markings onto fabrics, with the use of dressmaker’s carbon paper. Fig. 2.11 shows double and single tracing wheels with a pack of dressmaker’s carbon paper.

Not to be confused with conventional carbon paper which is very messy and leaves inky smudges on the fabric, dressmaker’s carbon paper has a coloured waxy finish and is used to transfer pattern markings onto fabric with the aid of a tracing wheel or pencil. (I use the one made by Hemline but there are others on the market.) Test on your fabric first to check the best colour to use. Try not to use a strong-coloured carbon paper on light-coloured fabrics as this may result in smudges. Use on the wrong sides (WS) of the fabric only.

Fig. 2.12 Manila pattern card and a pattern notcher with dotand-cross pattern paper.

Specific manila pattern card can be used for your corset block pattern, but any board will suffice providing it is fairly sturdy and can be cut neatly.

A pattern notcher is a nice thing to have, but is by no means a necessity. It will effortlessly cut small notches on the edge of card patterns. Sharp scissors will do the job just as well, albeit much more slowly. Fig. 2.12 shows manila pattern card and a pattern notcher resting on a sheet of dot-and-cross pattern paper.

Pressing Equipment

A regular steam iron and any size of ironing board are necessary for producing a neat corset with sharply pressed seams and edges.

If you have a sleeve board (which looks like a miniature ironing board), you will find it useful when pressing small areas, but it is not a necessity.

Use a tailor’s ham for pressing curved areas on your corset. The ham has different sized/shaped curves round its surface, so should accommodate any curves on your corset. The tailor’s ham is quite an expensive piece of equipment, but it is possible to make your own.

Fig. 2.13 A sleeve board and tailor’s ham are used for pressing small or curved areas of the corset.

Alternatively, you could use a rolled-up towel to pad out the curves of your corset whilst pressing. Fig. 2.13 shows a sleeve board and tailor’s ham.

A protective pressing cloth placed over your work will prevent shiny marks appearing after pressing. You can buy or make a silk organza pressing cloth which allows you to see where you are pressing and prevents the iron from pressing wrinkles into the fabric.

Eyelet/Grommet-Setting Equipment

Fig. 2.14 shows a variety of tools required for setting eyelets/grommets.

Fig. 2.14 Tools required for setting eyelets/grommets, including an awl, setting tools (anvil and driving pin), rubber mallet and eyelets; all are resting on a wooden board which protects the work surface.

An awl is a tool with a long, pointed spike used to make a hole in fabric by separating the fibres instead of cutting them, as a hole punch would do. If possible, use a tapered awl which will vary the size of hole required.

I recommend the tapered awl by Clover as this does the job perfectly and has a comfortable handle and a smooth tip which glides easily through the fabric.

My preferred method of inserting eyelets/grommets is with the two-part setting tool. The lower part, the anvil, has an indentation which houses the top of the eyelet. A washer is placed on the shank of the eyelet, with the fabric sandwiched in between, and then the driving pin is inserted into the eyelet. The top of the driving pin is struck with a rubber mallet to set the eyelet.

Do not use an ordinary hammer to set your eyelets.

The force is likely to split the eyelet or washer, or both. Instead, use a rubber mallet which will absorb the energy of the strike and set the eyelet without damaging it.

A wooden board will protect your work surface when setting your eyelets. I use an inexpensive wooden chopping board.

Eyelets can be inserted using multi-purpose pliers which will also insert rivets, studs and so on depending on the dies used. Dies are available in all types and sizes, and often are included in packs of eyelets.

Fig. 2.15 Hole cutters for use on fabric or paper: the wheel is rotated to select the hole size.

Hole cutters, as shown in Fig. 2.15, will cut holes into fabric or paper. Select the hole size required by rotating the wheel, insert the fabric, then squeeze the handles together. If you choose to use hole cutters, buy a good-quality pair to retain the strength and sharpness of the cutting edges.

Bone-Cutting Tools

Invest in a heavy-duty pair of tin or aviation snips, as shown in Fig. 2.16. You will need these to cut your spring steel boning into lengths. The steel is tough to cut through, so make sure the snips are sharp and strong, to prevent damage to your wrists when cutting. Always use with safely glasses or goggles.

Fig. 2.16 Tin/aviation snips for cutting steel boning; invest in a good-quality pair.

Fig. 2.17 Side cutters are used for cutting spiral wires to the required length.

Strong side cutters are used for cutting spiral wires to the correct lengths. Again, buy a good-quality pair that is easy to use and will not cause hand strain. Always use with safely glasses or goggles. Fig. 2.17 shows a pair of sturdy side cutters.

Fig. 2.18 Eye protection should be worn when cutting boning: goggles (above) and safety glasses (below).

It is vital to protect your eyes when using snips or side cutters. Safety glasses or goggles will shield your eyes from any pieces of flying metal. In Fig. 2.18 you will see a pair of safety glasses and wraparound safety goggles.

A metal file is used to smooth any rough edges on a steel bone or spiral wire after cutting and before tipping.

Fig. 2.19 Two pairs of needle-nose pliers and a metal file for smoothing jagged ends of bones and applying U tips.

You will need two pairs of needle-nose pliers to attach U tips to the ends of boning. These pliers have long, narrow jaws, making it easy to grip the U tip and squeeze it in both dimensions to attach it to the bone. Fig. 2.19 shows two pairs of pliers and a metal file needed to finish the bone ends.

Adhesive Products

Fig. 2.20 shows three types of adhesive that can be used in corset making.

Fig. 2.20 Adhesive products for corset making: Wonder Tape, Fray Check for controlling frayed edges and spray glue for attaching two fabric layers.

If you are making a double-layer corset, and you wish to bond the two layers of fabric together, spray glue is an easy way to accomplish this. The spray is a temporary adhesive which holds the layers together long enough to assemble the garment. I recommend 505 as it is easy to use and does not soak through the fabric, leaving marks; however, you will need to test it on a scrap of your fabric before using to check. (There are other brands on the market.) The glue comes in an aerosol can so must be used in a well-ventilated area.

I use Fray Check by Prym, a fabric glue