28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Edwardian fashions for women were characterized by the S-shaped silhouette, embellished with lace, tucks, ruffles, tassels, frills and flounces. This essential book includes eleven detailed projects, which form a capsule collection of clothing and accessories that might have been worn by an Edwardian governess, a woman travelling on an ocean liner, a campaigning suffragette, or a wife overseeing a busy household in a large country house. It explains making sequences in full and advises in detail on how to give the garments a fine, authentic finish. Eleven detailed projects are included, based on the dress collections at Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove, and Worthing Museum and Art Gallery. Each project includes a detailed description of the original garment, with an accompanying illustration alongside photographs of the original pieces, and scaled patterns are included for all projects with a list of materials and equipment required. Includes step-by-step instructions with information about the original techniques used and close-up photographs of the making process, with further chapters on tools and equipment, fabrics, measurements and sizes, and how to wear Edwardian fashion with ideas on creating new outfits from the featured projects. Also includes advice on how to adapt garments to make them suitable for both wealthy, leisured women, and for their poorer counterparts. Aimed at costume makers, museums and re-enactors and beautifully illustrated with 200 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

MAKING

EDWARDIAN

COSTUMES

FOR WOMEN

Suzanne Rowland

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2016 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

© Suzanne Rowland 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 103 1

Photographs by Benjamin Rowland

Illustrations by Joe McRae

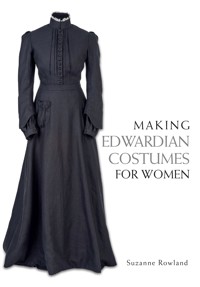

Frontispiece: Evening gown by Ida Pritchard. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery)

Dedication

To my mother Shirley Fenn

Contents

Introduction

1 Edwardian Fashion and Dressmaking

2 Tools and Techniques

3 Fabrics, Measurements and Sizes

4 Split Drawers and Chemise

5 Flounced Petticoat

6 Blouse with Tucks and Lace Insertions

7 Two-Part Walking Dress

8 Day Dress

9 Evening Gown

10 Lined Cape

11 Evening Bag, Hat and Parasol

12 Wearing Edwardian Fashion

Suppliers

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

Introduction

The selection of garments and accessories featured in this book are indicative of the kinds of projects made by an Edwardian dressmaker; this could have been a professional seamstress working from her own premises (it was a woman’s profession), a lady’s maid or a skilled hand batch-producing blouses by the dozen in a small workshop. Tailored outerwear and corsets have not been included because these were specialist areas outside of the dressmaker’s realm of experience. The garments and accessories featured are either from the collection at Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove, or Worthing Museum and Art Gallery, which gives readers the opportunity to make appointments with either museum to view the original pieces. Using museum collections poses some limitations for the researcher; it is widely acknowledged that historical clothing most often worn is likely to have been discarded; clothing saved for best is generally what survives and therefore makes up the bulk of museum collections. Fortunately both museums have diverse collections. Worthing Museum is a treasure trove of handmade and department store clothing. Due to the foresight of curators the collection contains unique pieces of everyday fashion; some in stages of disrepair, some perfectly preserved. The Royal Pavilion & Museums’ fashion and dress collection also holds examples of clothing from department stores from mid-range to high end. It contains a number of sub-collections, including the clothing of wealthy women such as Katherine Farebrother, Lady Desborough and the Messel family, who were dressed by the top London couture houses and professional dressmakers. Due to a longstanding association with both museums (as a volunteer at Brighton and as a museum educator at Worthing) I have been fortunate in developing a familiarity with the collections and I have benefited from having generous access to the collections for research.

Two fashionable evening gowns in pastel shades sketched by fashion illustrator Ida Pritchard. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery)

The criteria I used in selecting museum garments were as follows: firstly, all projects had to be suitable for reproduction; secondly, all fabrics and trimmings could be sourced without too much difficulty. A further objective was that projects should be adaptable and so projects have suggestions on how to adapt garments to make them suitable for both wealthy, leisured women, and for poorer women whose choices were limited due to a low income.

The Edwardian era, if characterized by the reign of Edward VII, stretches neatly from the beginning to the end of the first decade of the twentieth century (1901–1910). The sartorial influence of Edward and Alexandra, who married in 1863, extends beyond these boundaries, and therefore this book will cover a wider period stretching from the mid-1890s up to the mid-1910s. During the Edwardian period British society was rigidly divided by class, but by the end of the period things were changing due to new developments in the workplace and in industry.

Three dresses included in the book span the Edwardian era: a two-part walking dress with fitted bodice and trailing skirt from the turn of the century, a lightweight cotton day dress with pouched bodice and full sleeves from the middle of the era and a later style ‘Empire’ line evening gown with beaded tulle panels.

Not all garments in the collections are dated and others have approximate dates only. A close look at the tools and techniques used in garment construction can help with dating. Garments made before the First World War often used metal hooks and eyes as closures on collars and plackets. Wartime restrictions on the use of metal made it difficult for the companies producing hooks and eyes to keep up with demand and led to a limitation of stock and an increase in prices. An advertisement in the garment manufacturing trade journal The Drapers’ Record, 14 August 1914, by the firm Newey Bros Ltd, shows that the firm were reluctantly increasing the price of hooks and eyes due to a ‘great advance’ in the price of metal.

Researching projects began in the museum’s archives with the clothes and accessories and developed to include a range of additional sources. Worthing Museum has a wide selection of Edwardian dressmaking manuals and journal features in the archives, which include Isobel’s Dressmaking at Home, Weldon’s Illustrated Dressmaker and Weldon’s Home Dressmaker. They also have a boxed set of dressmaking booklets dating from 1914 to the early 1930s produced as a correspondence course by the Woman’s Institute of Domestic Arts & Sciences, which was based in Scranton, Pennsylvania. The course offered a range of valuable instructions for dressmakers, from how to stock and manage a workroom to how to become more proficient in the skilful use of a needle and thread when embroidering monograms on lingerie. The Drapers’ Record archive held at The London College of Fashion has been a useful source of research; further sources have included women’s journals, Government Reports, social surveys, dressmaking manuals, costume reference books and museum visits. I was particularly inspired by Janet Arnold’s comprehensive observations of museum dress captured in detailed sketches in Patterns of Fashion 2 (1982). Anne Buck’s careful study of garments and accessories made when she was Keeper of the Gallery of English Costume at Platt Hall, Victorian Costume (1961), was a further source of inspiration, as was Lou Taylor’s exploration of the development of dress through object-focused research in The Study of Dress History (2002).

Chapter 1

Edwardian Fashion and Dressmaking

1

FASHION FOR ALL

The defining shape of the Edwardian period is the S-shaped silhouette, which refers to the shape of a woman in profile. The flat-fronted corset, seen in advertisements from 1900 to 1908, provided the first layer of shaping to the body, although it did not shape in the extreme way suggested by corset advertisements. The ‘Erect Form’ corset was featured in The Drapers’ Record in 1902 and showed an exaggerated version of the fashionable shape with a tiny waist, large bosom and protruding rear end. Much of the exaggerated shaping of the S-shaped silhouette was achieved by the outer layers of clothing, which included pouched front blouses and skirts that were flat at the front, smooth over the hips, with soft pleats or gathers at the centre back sitting on top of a similarly shaped petticoat. High fitted collars, trailing skirts and large hats, all decorated with flounces and embellishments, completed the look. Edwardian fashion was not always practical, or indeed comfortable. The straight fronted corset had the effect of flattening the stomach and encouraging the lower back to arch. The trailing skirts could also be a hindrance, as recalled by the Prime Minister’s daughter-in-law, Lady Cynthia Asquith, in her memoir Remember and Be Glad:

… the discomfort of a walk in the rain in a sodden skirt that wound its wetness round your legs and chapped your ankles… Walking about the London streets trailing clouds of dust was horrid. I once found I had carried into the house a banana skin which had got caught up in the unstitched hem of my dress.

The shape of a sleeve was one of the most changeable features in fashion, although one constant feature was a tight fit around the armhole. Writing in the New London Journal in 1906, journalist Mrs Humphry wrote of sleeves that were inserted too far back and sleeves that were tight on the fleshy part of the arm, and other sleeves ‘that would insist on being a mass of wrinkles, no matter what you did to coax or coerce them.’

Corset advertisement in The Drapers’ Record showing an exaggerated form of the S-shaped silhouette, 1902. (© EMap and the London College of Fashion Archive)

For the fashion-conscious woman the influence of ‘the latest fashions from Paris’ cannot be overstated. Even cheap penny weekly Home Chat had a section entitled ‘Our Paris Letter’, a fashion feature written by the glamorously named correspondent Yvonne D’Ivoire. In March 1895 she wrote of her admiration for imitation tortoiseshell hairpins in the shape of tiny wings. Fashion tips from Paris also feature heavily in the upmarket weekly journal The Ladies’ Field and were reported upon by the well-known fashion correspondent Mrs Eric Pritchard. On 3 February 1906, Mrs Pritchard described a new fashion for linen collars: ‘Parisians have them made of immense height, of beautiful linen, with a distinctive cachet in a little handwork … [which] adds a dainty little suggestion of refinement’.

Detail of a hand-painted fashion plate showing a green and white striped day dress from Barrance and Ford, Brighton, Ltd. (Peter Hinkins)

For a wealthier woman, dressing in a complete ensemble from embroidered silk stockings to her immaculately coiffured hair was a time-consuming process. A lady’s maid was essential to help with dressing, to carry out clothing repairs, and to make alterations. If a maid possessed good dressmaking skills she might also make a lady’s underwear. The maid would be kept busy throughout the day and evening because Edwardian etiquette required several changes of clothing to fit each new social occasion. Cynthia Asquith recorded the garments needed for a typical country house visit in the early 1900s:

A Friday-to-Monday party meant taking your ‘Sunday best’, two tweed coats and skirts with appropriate shirts, three evening frocks, three garments suitable for tea, your ‘best hat’ … a riding habit and billycock hat, rows of indoor and outdoor shoes, boots and gaiters, numberless accessories in the way of petticoats, shawls, scarves, ornamental combs and wreaths, and a large bag in which to carry your embroidery about the house.

The fashionable clothing worn by Katherine Sophia Farebrother (1857–1928), the wife of a Salisbury solicitor, features in the collection at Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove. The Farebrother collection consists of over twenty dresses and accessories. When her husband died in 1913, Katherine’s clothes were packed away and she went into mourning until her own death in 1928. The collection remained undiscovered for over sixty years and only came to light during a house move. The Royal Pavilion & Museums’ records contain information obtained from Katherine’s grandson which provides an insight into her lifestyle: ‘Besides herself, her husband and three children, she organized a household of four servants, interviewing the cook each morning at 10 o’clock.’ It is fascinating to observe a collection of clothes belonging to one woman and to form a sense of her personal taste and her financial means. Katherine Farebrother was said to be a talented artist and the collection shows that she occasionally wore artistic dress. The bulk of the collection, however, is comprised of more conventional clothing purchased from smart London department stores such as Dickins and Jones, and Harvey Nichols. She also used the services of local dressmakers although she was apparently a good, plain needlewoman herself.

For women who were not wealthy enough to shop in smart London department stores it appears that there were still opportunities to partake in fashion. Young working-class women employed in the Birmingham and Coventry metal trades were observed by a health and safety inspector for a government report in 1908. The report provides conclusive evidence of factory workers wearing fashionable clothing. The inspector observed:

There are hundreds of girls engaged at fairly clean work in the Birmingham and Coventry metal trades operating the lighter milling machines and lathes. Very many of these girls are arrayed in flimsy, stylish attire, including blouses with loose sleeves and trimmings, and the hair expanded loosely with strands escaping, either by accident or design, from their fastenings.

The report not unsurprisingly sounds disapproving of women wearing fashionable clothing to work. This relates to the looseness of their clothes and the possibility of something getting trapped in the machinery, and could also relate to the ‘flimsy’ nature of the garments. The idea of young working-class women wearing delicate clothing would imply that they were dressing outside of the expectations for someone from their class of society.

In order to understand the spending habits of working-class families between 1909 and 1913 Maud Pember Reeves and other members of the Fabian Women’s Group recorded the daily lives and budgets of families in Lambeth, East London, in the publication Round About a Pound a Week. All families had a husband in regular employment and survived on a basic income of about a pound a week. Pember Reeves was mystified by the lack of money for non-essentials like clothing, and concluded that if new clothes were bought then the already sparse weekly food budget would be reduced. For the majority of families clothing was either handed down, homemade or bought from a secondhand market stall. The everyday clothes worn by most Lambeth women were a blouse and patched skirt with a sacking apron tied on top.

Young unmarried working women were a significant group of consumers of fashionable clothing. Known as the ‘New Woman’ or ‘Gibson Girl’, after the fictional character drawn by American illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, they required smart and respectable clothing to enter the world of office work. The Gibson Girl was often depicted in illustrations wearing a masculine influenced shirt and tie whilst riding a bicycle. Such was the appeal of this character that The Ladies’ Field featured a Gibson Girl shirt pattern available by mail order in 1903. The Ladies’ Field described the Dana Gibson shirt as the ‘highest triumph’ in shirt evolution and keenly praised American women for demonstrating how to wear it. While the New Woman was a cultural step towards emancipation, the women’s suffrage movement was a political one. Suffragette members of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) were given advice on what to wear and this included a lightweight blouse and plain wool skirt, nothing that detracted from their important message.

DEPARTMENT STORES OFFERING MADE-TO-MEASURE

One of the first department stores was William Whiteley’s Emporium, which opened in Westbourne Grove, London in the latter half of the mid-nineteenth century. Other stores followed in London’s West End, which rapidly became a fashionable destination for shopping. Stores such as Debenhams and Freebody employed seamstresses in workrooms on the premises to make and alter clothing. The seamstresses are captured in two black and white photographs, now in the National Archives at Kew, in which women are shown sitting shoulder to shoulder around long tables, sewing by hand with electric lighting overhead. For customers unable to travel to the large department stores a mail order service was offered for patterns and part-made clothing that could be fitted at home and finished to suit the customer. Catalogues and bound volumes produced by the stores featured sketches of fashions rather than photographs; these presented women with a glamourized ideal version of femininity. Worthing Museum holds the archive of fashion illustrator Ida Pritchard who sketched promotional material for the Peter Robinson department store in London’s Oxford Street between 1906 and 1914. She was a skilled illustrator who sketched plates in colour or monotone; her figures were stylized but not wildly unnatural.

Photograph of fashion illustrator Ida Pritchard. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery)

The upmarket department store Marshall offered a mail order service catalogue in 1909. The company boldly stated, ‘We believe that this catalogue will be appreciated by ladies living at a distance from London who wish to wear fashionable garments concurrently with the leaders of fashion in the principal cities of the world’. Dressmaking patterns by mail order were also available to those living abroad. In 1907 an advert in The Queen by the London firm Kentish encouraged ‘ladies living in the country or colonies’ to order smart tailor-made gowns with the promise of an accurate fit. In Knightsbridge, Harrods department store sold both readymade and made-to-measure fashions. Worthing Museum has a commemorative book celebrating the firm’s Diamond Jubilee in 1909, which contains a section devoted to each department in the store. The dressmaking service gave customers the opportunity of choosing fabric and a pattern to have a garment made on the premises. Another option was to buy an ‘unmade’ robe which was a partly constructed gown adapted and finished to fit an individual customer.

Internal view of the bodice of an evening gown showing fabric channels inserted with whalebones, finished at the ends with orange flossing. Waist stay woven with the name of the Brighton department store Leeson and Vokins. (Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove)

Advertisement for Kentish, Ladies’ Tailor, for plain tailor-made or dressmaking gowns, The Queen, Saturday 20 July, 1907. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery)

Outside London, regional department stores in larger towns and cities offered similar services. Leeson and Vokins department store opened in Brighton in 1882 and by the Edwardian period was well established as a destination for purchasing the latest fashions. Royal Pavilion & Museums has a selection of clothing and accessories from the store including the beaded evening bag recreated in Chapter 11. The University of Brighton’s Design Archive holds the Vokins’ Archive; this contains advertising materials and leaflets which demonstrate that customers were regularly invited to fashion shows to view the latest ‘novelties’ to arrive in store. Advertising materials stress that everything was sold at a reasonable price, which is useful for understanding the profile of the woman who might have purchased the beaded evening bag. Photographs of the store show well-stocked departments with rows of bentwood chairs for customers to rest in while an assistant attended to their needs.

DRESSMAKING

The ease of availability of paper patterns coupled with the rise in popularity of the domestic sewing machine allowed many women to make their own fashionable clothes at home. Weekly journal The Ladies’ Field encouraged readers to try their hand at making their own clothes, in October 1907, by stressing the large variety of materials available and the advantage of getting a good fit.

Dressmaking was also a way for women to earn an income and the Edwardian dressmaker was a fixture in all levels of society, from Lucile (Lady Duff Gordon), designer and maker of beautiful and expensive gowns for society ladies, to an East End grocer’s wife who earned a little extra money by making blouses for her neighbours. At the upper end of the market women could select a design from a hand-painted bound volume of designs. The beautiful autumn 1905 collection from Lucile is one example (reproduced in full in Lucile Ltd: London, Paris, New York and Chicago, 1890s–1930s by Valerie D. Mendes and Amy de la Haye). The Brighton-based dressmakers Barrance and Ford also produced bound volumes with a range of colourful fashion plates for customers to view at the shop or in their own homes. For women wanting to make their own clothes there was a range of dressmaking manuals offering tips and advice to improve skills or learn a new technique.

Front cover of Weldon’s Home Dressmaker, No. 189, advertising free paper patterns of a Day Gown and Evening Dress. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery)

Edwardian paper patterns were often given away free with women’s journals but this was not always the case. In 1901 the dressmaking journal Isobel’s Dressmaking At Home advertised individual patterns for sale by post, claiming to be the cheapest in the world. An afternoon blouse pattern to buy was advertised at 6d with free postage and packaging. One free pattern was included in this particular edition: a skirt with a bias-cut peplum. For younger women, wanting to make dressmaking their profession, an apprenticeship combined with an education at a trade school was an option. In 1904 the Borough Polytechnic in south east London was offering a waistcoat-making course for girls as just one of several options. The social campaigner Clementina Black visited the school to learn about the benefits of educating girls in this way and wrote of seeing girls designing and making miniature sleeves and skirts that were then submitted to an advisory committee for comment and inspection. Making a miniature version was a method of testing a technique by using a minimal amount of fabric in a shorter space of time. Once the apprentices had qualified it was relatively easy to find work as a dressmaker. There were disadvantages to the profession, however, because it was a seasonal trade, but the main disadvantage for women was the low rates of pay. A Government Report from the Select Committee on Home Work in 1908 provides information on the pay and working practices of makers such as ‘Miss A’ who had eighteen years’ dressmaking experience. She worked on a ‘fast sewing machine’ which she had bought using the instalment system and paid for on a weekly basis. She worked long hours for a warehouse in the West End of London making blouses from home for which she earned between six and seven shillings a week, a very poor income at that time. Miss A explained the process of making a blouse to fit a specific size, which required a degree of skill. She received all pieces already cut out for each blouse and added the lace and all trimmings. It was important to make it to the correct size and she had a dress stand to ensure this was achieved. She explained, ‘I have to put it on a stand, and shape the necks, and make it fit in all parts – make the arm-holes the right size, and make the necks to size.’

Postcard of a young woman wearing a blouse and skirt with a straw hat, 1907. (Kat Williams)

Domestic sewing machines were readily available to Edwardian dressmakers. On 26 September 1914 The Drapers’ Record carried an advertisement for Jones Domestic Sewing Machines, described as silent, ‘light-running’ machines that could be operated by hand or by foot using a treadle table. More information about tools and techniques features in the following chapter. Chapter 3 focuses on a selection of fabrics and provides advice on taking measurements. Each subsequent chapter is dedicated to the recreation of a museum garment or accessory. The final chapter looks at the wearing of Edwardian fashion and gives ideas for combining the projects featured in the book to create a variety of new outfits.

Chapter 2

Tools and Techniques

2

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

The projects in this book are suited to those with sewing experience but I would encourage anyone with an interest to have a go at a project that they find interesting. The instructions for making have been written using my positive experiences of teaching dressmaking to many adult learners ranging from complete beginners to skilled makers. The techniques are all based on my experiences of working in theatre and film costume workrooms for many years. The advantage of working alongside skilled cutters and costume makers is that many tips are shared in a workroom, some of which I have been able to pass on in this book. All projects are presented with a series of step-bystep photographs and written instructions and, where possible, photographs showing details of the original museum garments and accessories have also been included. Breaking down projects into smaller tasks means that one section can be completed at a time and a good result achieved before moving to the next stage.

Once a project has been selected there is a list of materials, tools and equipment to help get started. Each chapter has a main photograph of the completed garment or accessory. Because some of the museum garments are in need of conservation it was not possible to mount them on mannequins to take photographs and so black-and-white illustrations showing detailed features of the original garments have been included. The sketches express the clothing as it is now, that is to say clothing that has been worn and used rather than in pristine condition. Specific instructions are given in each chapter on the cutting of fabrics and linings with a making sequence to follow to achieve the best results. Additional information and hints on adapting garments for the stage, and for a range of social classes, is also provided at the end of each chapter. Many projects have some form of embellishment, including pin-tucks, tucks, ruffles and beading, which are enjoyable to create but also extremely time consuming. Where a technique is repeated, for example the beading pattern on both sides of the drawstring evening bag, only one side has been completed on the reproduction bag. Some garments have been slightly simplified, such as the blouse where there are fewer insertions of lace running down each sleeve. In each case this is explained, and descriptions and, where possible, photographs of sections of the original garments showing the techniques, are provided alongside the illustrations.

Costume-making equipment.

It is important to note that all patterns are reproduced without seam allowance and it is suggested that a generous seam allowance is added to patterns and trimmed down only after a fitting has taken place. If a true reconstruction of the inside of an original garment is desired then the finished seam allowance should be narrow. The seam allowance observed on most of the original garments was a scant 1cm, which allowed Edwardian dressmakers to be economical with their fabric. In theatre costume a much larger seam allowance is left to enable alterations at a later stage, for example if a production is revived with a new cast.

Taking patterns from original garments poses a few challenges: in some cases, due to the age of the garments, stretching, disintegration, wear and tear, and alterations may have distorted the original garment. Even when a garment is in a good state of repair, allowances need to be made for the fact that Edwardian women differed in shape from women today due to a different combination of underwear, diet and exercise. The renowned theatrical costumier Jean Hunnisett studied paper patterns from French fashion journal La Mode Illustrée between 1900 and 1909 for her book Period Costumes for Stage and Screen: Patterns for Women’s Dress 1800–1909, and noted that the Edwardian woman had a narrower back, a wider front and, perhaps not surprisingly, a smaller waist. Taking these concerns into account the patterns featured in the book are a contemporary adaptation of the Edwardian silhouette. The aim has been to retain the period look of each piece but to make the patterns suitable for a modern shape.

HOW TO USE THE PATTERNS

CF – Centre Front

CB – Centre Back

SS – Side Seam

Grain Line – place the pattern piece on the fabric so that the grain line follows the straight grain of the fabric

Fold – place the pattern piece along a folded edge

Cut 2 – cut two pieces with the same pattern piece

Darts, tucks, gathering and balance points are also included on the patterns.

How to enlarge patterns

The method suggested for scaling up the patterns in the book is to use pattern paper marked with a 1cm grid of squares. The best results will be achieved by working with only one pattern piece at a time and using a Pattern Master. Those proficient in scaling up using a photocopier will be aware that distortions can occur using this method. In all cases the pattern must be tested by making a toile and carrying out a fitting before cutting in fabric.

Adding seam allowances and transferring markings

Seam allowance is added directly to the fabric by tracing around the pattern pieces once they have been pinned to the fabric. How much seam allowance to add depends on the type of garment and what it is being made for. Commercial sewing patterns add 1.5cm to most seams but costume makers have to consider fittings and alterations and so at least 2cm should be left and more may be preferred. To add seam allowance to heavier fabrics and mounting fabrics, use a sharp piece of tailor’s chalk to draw around the edge of the pattern. Also use tailor’s chalk to mark darts and other balance marks. Once all pieces have seam allowance and have been cut out, marking can be transferred to the reverse side with carbon paper and a tracing wheel. For lighter fabrics, where the chalk and carbon paper will show through to the right side, temporary lines can be drawn with an air erasable marker. Thread tracing can be also be used, which involves tacking with double thread along a line, snipping the top threads, then carefully pulling the pieces apart and then snipping the threads between the two pieces. The making instructions in this book suggest pinning and then machining and do not include tacking in the process, although tacking can be included if required.

Making a toile and samples

Although it might seem like an additional and time-consuming process, making a toile actually saves time in the long run. A toile should be made before making up any projects in this book. A toile can be made from calico, muslin or similar fabric and all seams should be sewn with a long machine stitch to make unpicking easier afterwards. Toiles can be unpicked and the newly marked shape transferred to the pattern piece. As well as helping to test the fit of the pattern the toile can also be used to test techniques. Techniques can also be tested on smaller pieces of fabric to be used for a project. If pin-tucks or a flat felled seam have not been attempted before it is better to perfect the technique by making a sample before working on the actual garment and running the risk of having to unpick a mistake.

TOOLS

Having the right tools for a job makes the job easier; similarly, the wrong tools or poorly maintained tools add an extra level of difficulty. Many dressmaking tools and techniques used in the Edwardian era are still in use today. A further aspect to consider is a place in which to work. Ideally this would be a fully equipped workroom but many beautifully made garments have been created on a kitchen table. If you are lucky enough to have a workroom then a large cutting table at waist height is a useful aid.

Iron and board

A steam iron and a sturdy ironing board with a clean cover are essential items. A further useful item is a sleeve board, which can be used to press sleeve seams and small details. Theatre costume departments use industrial steam irons and ironing tables with a foot-operated vacuum press – this helps to hold the garment in place while the maker uses both hands for pressing. A pressing cloth made from a lightweight natural fabric can be used dry or damp as a barrier between the shiny surface of the iron and delicate or woollen fabrics. Fabrics require different temperatures and ironing techniques and it is worth testing a scrap of fabric before putting the iron on the actual garment.

All fabrics should be pressed before cutting. To achieve a professional looking garment each stage should be pressed in the making process before moving on to the next stage. Whilst work is in progress the garment should be folded over a hanger and kept neatly stored until completed.

Tailor’s pressing tools

A tailor’s ham is a cloth-covered pad that feels firm to the touch and (perhaps unsurprisingly) is shaped like a ham. It is useful for pressing hip seams or wherever there is a curved seam. A sleeve roll performs a similar function and is useful for inserting into sleeves to press seams. A tailor’s pressing glove is useful for pressing garments on a dress stand. The padded glove or mitt is worn on the hand and placed inside the garment while the other hand operates the iron. For woollen fabrics a smooth block of wood known as a tailor’s clapper can be used to ‘block’ or flatten an area directly after pressing. The block is held firmly in place for a few seconds after a burst of steam has been directed at the fabric.

Scissors

Scissors vary in size, with 8-, 10- or 12-inch blades; the longer blades are used by tailors and are also known as shears. Dressmaking scissors and shears are available for right- and left-handed users and should only be used for cutting cloth and threads. Three pairs of scissors are needed for the projects in this book: one for cutting out fabric, a separate pair for paper, and small, sharp scissors for cutting threads and buttonholes. For the Edwardian dressmaker the best scissors were those made from Sheffield Steel. An advertisement for the firm Cox & Co. shows cutting scissors with leather covered handles and small buttonhole scissors, which would have been useful for cutting hand-worked buttonholes on delicate fabrics.

Advertisement for a range of Sheffield Steel scissors in The Lady’s World. (Worthing Museum and Art Gallery)

Seam ripper

No matter how experienced a maker is there is always the possibility of making a mistake when sewing. Edwardian dressmakers used a small sharp knife for ripping seams apart. A razor blade was another option. A tailor I used to work with used a small folding penknife for cutting threads, which hung from a piece of elastic tied to his belt. As an alternative a seam ripper (also known as an unpicker or stitch ripper) is available in two sizes. Small, sharp scissors can also be used.

Tape measure

A good quality tape measure printed in both metric and imperial measurements is an essential piece of equipment. A tape measure should not be wound into a tight swirl in case stretching should occur. Edwardian tape measures were advertised as being 60 inches long. A small sewing gauge is also useful for measuring small areas and for marking hems. The ‘Picken dressmaker’s gauge’ was patented in 1915 and is described in the Woman’s Institute of Domestic Arts & Sciences booklet Essential Stitches and Seams. It could be used for marking tucks, plaits and ruffles, as well as hems, buttons and buttonholes.

Expandable button spacer

This is a useful tool for working out the spacing of buttons, fastenings or pleats and was not something an Edwardian dressmaker had the benefit of owning. It is lightweight and folds away, and can easily be stored in the bottom of a workbox.

Long ruler

A metre-long ruler is valuable for measuring fabric and is essential for pattern cutting. A folding metre stick is lightweight and convenient for taking into archives (if allowed).

French curve

A flat curved tool used for drawing curved edges. The Pattern Master performs the same role and is another essential tool for costume makers.

Drafting paper

A roll of dot and cross paper marked at 1 inch or 2.5cm intervals is a worthwhile investment. Squared paper marked at 1cm intervals and plain newsprint can also be used.

Hand sewing needles

Hand sewing needles were an essential item of equipment for Edwardian dressmakers, some of whom did not have access to a sewing machine and therefore made whole garments by hand. The size of needle varied to suit each task with short, fine needles used for small stitches. Having the right sized needle was essential to complete each process skilfully and in good time. A good set of assorted needles is useful, with additional needles for specific jobs. For example beading needles are long and fine and fit through the opening of the tiniest bead.

Sewing threads

To replicate Edwardian garments accurately, natural sewing threads should be used. A 1902 advert for sewing thread in The Drapers’ Record for Gütermann & Co. shows that the firm produced sewing silk and machine twist. Buttonhole twist was also available – this is a thicker thread used for hand sewing buttonholes. To match the colour of the sewing thread to the fabric, unroll the end of the thread and place it on top of the fabric (this should be done in natural light). If an exact match cannot be found then select a shade darker.

Advertisement in The Drapers’ Record for ‘REFORM’ sewing silks and machine twist for manufacturers. (© EMap and the London College of Fashion Archive)

Fray Check

The Edwardian dressmaker certainly would not have heard of this product but it is invaluable to the contemporary costume maker. A dab of liquid Fray Check can be used to strengthen corners or to stop threads from fraying on delicate work. Other brands are available.

Bodkin

A bodkin is a flat, blunt needle with a large eye, useful for inserting ribbon through lace or elastic into a casing. A safety pin is an alternative suggestion.

Pins

‘Cheap pins are not an economy,’ warned the Woman’s Institute of Domestic Arts & Sciences in Essential Stitches and Seams, and this is still the case. Cheap pins have a tendency to bend, break or rust and therefore stainless steel pins are the best option. Costume workrooms tend to use magnetic pincushions, which are also useful for picking pins up from the floor.

Turning tool

The social campaigner Clementina Black wrote in her study of women’s working practices published in 1915, Married Women’s Work, of collar makers in London performing the ‘turning process’ which was the act of turning the collar the right way round once it had been stitched. She observed that it was a tricky process and that most makers used a bone tool to poke the corners out to achieve a neat finish. A bamboo collar turner from Merchant & Mills is a useful modern equivalent.

Beeswax

Sewing thread is pulled through the edge of a block of beeswax to coat the thread with a layer of wax for extra strength. Tailors use beeswax for coating buttonhole twist when sewing a hand-worked buttonhole.

Thimble

A thimble protects the middle finger of either hand depending on whether the maker is right- or left-handed. Indentations in thimbles are there to make it easier to push the blunt end of the needle through fabric. Tailor’s thimbles are open-ended because the tailor pushes the blunt end of the needle through layers of cloth and canvas with the side of the finger rather than the tip. The Woman’s Institute of Domestic Arts & Sciences advised that the thimble ‘should not be tight enough to stop the circulation of blood in the finger, and yet not loose enough to drop off when you are sewing.’ The Edwardian dressmaker had the option of purchasing a practical yet decorative thimble from a jeweller or ‘fancy dealer’. The Dorcas thimble, for example, was made from three layers of steel and silver, not only to make it more comfortable but also to make it more resistant to damage.

Tailor’s chalk and marking pens

Tailor’s chalk is available in several colours, in either triangular or squared shapes. The edges of the tailor’s chalk should always be kept sharp, either with a tailor’s chalk sharpener or by using the blade of paper scissors. An alternative is an air erasable marker although it is advisable to test the marker on a scrap of the fabric before use. Water-soluble markers are also available.

Tracing wheel