11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Designing and making successful automata involves combining materials, mechanisms and magic. Making Simple Automata explains how to design and construct small scale, simple mechanical devices made for fun. Materials such as paper and card, wood, wire, tinplate and plastics are covered along with mechanisms - levers and linkages, cranks and cams, wheels, gears, pulleys, springs, ratchets and pawls. This wonderful book is illustrated with examples throughout and explains the six golden rules for making automata alongside detailed step-by-step projects. Magic - an unanalyzable charm, a strong fascination so that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Superbly illustrated with 110 colour photographs with examples and detailed step-by-step projects.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 142

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Robert Race

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2014 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Robert Race 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 745 8

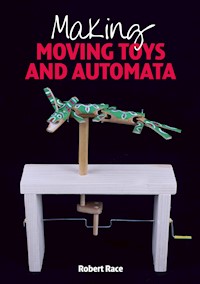

Frontispiece: The Motley Crew.

Picture credits

Page 8 ©Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, NL.

Page 9 (bottom) Library of Congress, prints and photographs collection. LC-USZ62-110278.

Page 10 Los Angeles County Museum of Arts.

Page 20 D. J. Shin, CC BY-SA3.0

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to all the makers, named in the text, who have generously allowed me to use pictures of their work. Many thanks to them, and thanks also to the anonymous makers of the simple, but ingenious, mechanical toys that so inspire me, and special thanks, for all her support, to my wife, and favourite Muse, Thalia.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1. MAKING AUTOMATA

2. MATERIALS

3. MECHANISMS

4. MAGIC

5. THREE PROJECTS

6. USEFUL STUFF AND WHERE TO FIND IT

INDEX

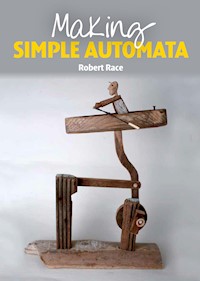

Canoe with Birds. A simple automaton, made by the author in driftwood.

INTRODUCTION

WHAT ARE AUTOMATA?

Automata is the plural of the Greek word automaton, meaning a thing that moves of itself. The plural can also be automatons, but it is less common. Rather more common, but not strictly correct, is the use of automata for the singular. Modern dictionaries give a broad spectrum of definitions and usage. Sometimes the word has a narrow specialized application, such as in the mathematical concept of a cellular automaton. It can be applied to a person, or to a living creature in general, when it suggests a possibly efficient, but merely mechanical action, without thought or feeling. One of the common usages of the word focuses on the notion of a mechanical device that moves, is usually intended as a toy or amusement, and often imitates the action of a living creature. There may be reference to a concealed mechanism and motive power. Although automata can be quite complicated machines, mimicking the movements of human beings or animals, even performing complex actions such as drawing a picture or writing, the Oxford English Dictionary gives a clockwork mouse as an example.

This book deals with the design and construction of small scale, simple mechanical devices made for fun. I shall call them automata, although in many, the mechanism, rather than being concealed, is in full view and intended to be part of the overall effect. The source of motive power and its transmission are also often clearly visible. Power may be provided directly by turning a drive shaft with a crank handle, or less directly, for instance by raising a weight or winding a spring.

The oxford english dictionary suggests a clockwork mouse as an example of an automaton.

THE HISTORY OF AUTOMATA

That the OED gives a clockwork mouse as an example of an automaton indicates that it is pretty impossible to disentangle the history of automata from the history of moving or mechanical toys, not to mention that of puppets and dolls, of kinetic sculpture, of theatrical devices, of conjuring or of robotics.

If you look at such histories you will find the same passages from classical authors, and the same museum objects, claimed as early references to, and early examples of, automata, or of moving toys, or of dolls, or of puppets and so on.

Figure Kneading dough. An ancient moving toy, operated by pulling a string. egypt, around 2000BCE.

It is well worth following these histories. Since prehistoric times the urge to represent living things by animating them has been a significant factor in the development of technology.

Among the toys, or toy-like objects, found in ancient Egyptian tombs are a variety of jointed figures with movable limbs, and animals with moving jaws, operated by pulling a string. One notable example that survives in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo is an ivory sculpture of three dancing dwarves mounted on a base: strings can be pulled to rotate the figures (a fourth figure from the group is in the Metropolitan Museum, New York).

A number of moving toys, including wheeled toys, dolls with movable limbs and figures operated by pulling a string, survive from ancient Greece, and also from earlier civilizations, such as those in Mesopotamia and the Indus valley.

References to automata, moving toys and puppets in classical texts are sparse, and often difficult to interpret with any certainty, but they do suggest that such things were familiar objects in ancient Greece. For example, in Chapter 7 of The Republic, in the well-known allegory of the cave, Plato pictured puppets, with their operators hidden behind a wall below, casting shadows on the wall. Aristotle, in De motu animalium, compared the movement of animal limbs to automata (by which he probably meant some sort of puppet, or mechanical theatrical device) and also to a strange-sounding toy cart, which runs in a circle because the wheel, or wheels, on one side are smaller than on the other.

Solid descriptions of more complex automata first appear in the second and first centuries bce in the works of the Alexandrian school, and particularly of Ctesibius, Philo and Hero. A wide variety of hydraulic, pneumatic and mechanical devices are described in the texts that survived. Some of these, such as clepsydrae (water-clocks), are machines with a really practical purpose, but they often incorporate moving figures, singing birds and, literally, bells and whistles. In addition, many are really just automata – intended to mystify theatre-goers and temple-goers, or simply to amuse.

These texts survived because they were transcribed by Byzantine and Arab scholars. They subsequently had a considerable impact on Renaissance Europe when Latin translations appeared during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Woman with Rolling Pin, by a modern maker, Edessia Aghajanian. In the British Museum there is a terracotta string-pull toy from Rhodes, dating from 450bce, showing the same timeless domestic task.

Hero’s device for automatically opening temple doors when a fire is lit on the altar. From Giambattista Aleotti’s work of 1647.

Under Harun al-Rashid, the fifth caliph of the Abbasid dynasty, who succeeded in 786ce, and under his successors, Baghdad became an important centre of learning, not least in mathematics and science. Scholars at the House of Wisdom actively sought Greek texts, such as Euclid’s Elements, to translate into Arabic. Among them were the three Banū Mūsā brothers who produced the Book of Ingenious Devices including an array of hydraulic and pneumatic automata including trick vessels, automatic fountains and music machines. They drew heavily on the work of Philo and Hero, but introduced many original features of their own.

Another important figure in the history of automata is the brilliant engineer Al-Jazari, who, in the late twelfth century was in the service of three successive Artuqid rulers in the city of Āmid, now Diyarbakir in Eastern Turkey. His amazing Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices appeared in 1206CE. It also draws heavily on the Alexandrians, and on the Banū Mūsā brothers’ developments. It has numerous coloured drawings of automata and other hydraulic, pneumatic and mechanical constructions, many involving delicate control mechanisms, and highly sophisticated water clocks and a boat with four mechanical musicians operated through a camshaft. The drawings are detailed, if sometimes difficult to interpret. Al-Jazari’s designs use mechanical devices, such as crankshafts and camshafts, and are technologically advanced in the use of segmental gears, and of conical valves with the seats and plugs ground down to give a watertight fit.

Al-Jazari’s design for a candle clock, with a system of weights and pulleys, releasing twelve balls to mark the hours.

Grottoes, fountains and mechanical theatres

Translations of Hero and Philo started to appear in Europe at the beginning of the sixteenth century. The hydraulic and pneumatic devices that they described were used enthusiastically in princely pleasure gardens with ever more elaborate fountains and grottoes with mechanical music, moving figures and automated scenes. The motive power was provided by flowing water, but the mechanical elements became more and more complex, using pulley systems, camshafts and crankshafts to animate individual figures and even whole theatrical scenes.

These garden embellishments were the preserve of the seriously rich and powerful – they were expensive to build and difficult to maintain. Many of the more intricate mechanical elements did not last. However, a famous example of these waterworks was installed early in the seventeenth century at Schloss Heilbrunn near Salzberg and many of the effects survive, although the hydraulic mechanisms are not original. In the eighteenth century the Nuremberg craftsman Lorenz Rosenegge installed an extraordinary model theatre, which is also still in working order.

Lorenz rosenegge’s water-driven mechanical theatre added to the attractions in the gardens at schloss Hellbrunn, salzberg, in the mid-eighteenth century.

Clockwork

In 807 one of the gifts that Harun al-Rashid presented to Charlemagne was a clepsydra (water clock) in which twelve horsemen appear in turn and twelve balls fall onto cymbals to strike the hours. There were plenty of other opportunities for the advancing technologies used in clepsydrae (water clocks) in the Arab world to pass into Europe, principally through Muslim Spain. Complicated water clocks became widely used in medieval Europe, and usually they would include various automata, such as figures to strike a bell to mark the hours. From the end of the thirteenth century weight driven clocks, with an escapement mechanism to control the fall of the weight, started to replace them. The word clock comes from the French cloche, Latin clocca, meaning bell, and the earliest had no hands, indicating the passage of time by the ringing of a bell. The principal purpose, for these mechanical clocks, as for the clepsydrae that preceded them, was to measure the fixed canonical hours of prayer. They were substantial structures, and typically mounted on a tower. Just as the makers of clepsydrae often incorporated animated figures, opening doors and singing birds, the mechanical clock makers incorporated animated strikers of the bell to be operated by the weight-driven clockwork mechanism. These were known as jacks of the clock, or jaquemarts.

By the late fourteenth century dials were being added to the clocks. At first the dial rotated and a fixed hand indicated the time, but soon a rotating hand sweeping around a fixed dial became the norm. Mechanical clocks developed rapidly. There would be more than one jack to strike the bell, and different sets of figures might appear through doors at the hour and at the quarters, circling around at the front. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries many churches also had automata associated with the organ, and mechanical figures of Christ on the cross, or of devils and angels, were not uncommon.

A jack of the clock in Wells Cathedral. The figure strikes the bell in front with a hammer, and two bells with his heels.

Gradually the mechanisms of large public clocks were refined and miniaturized, as were the automated figures associated with them. During the sixteenth century, notably in southern Germany, increasingly sophisticated animated human figures, androids, and devices on a domestic scale, such as the table decorations based on the nef were constructed. The nef was a model ship, originally for storing utensils and spices, but it developed into an elaborate mechanical ornament incorporating a clock, with many little automated figures.

By the eighteenth century there was a growing appetite throughout Europe for ever more life-like and active mechanical figures, powered by more complex clockwork, with springs, weights, gear trains, wires, chains, pulleys, bellows, cranks, camshafts and levers. In 1738 Jacques de Vaucanson, a brilliant mechanician and astute showman, exhibited Le Flûteur (The Flute Player) in Paris. This was an extraordinary life-size figure, mounted on a plinth that concealed the complicated mechanism which controlled the flow of air, changed the shape of the mouth, moved the steel tongue, and operated the fingers. It could play twelve melodies. The following year he added two more automata: the first was a figure that played the traditional Provençal combo of galoubet et tambourine (pipe and tambour) faster than any human player. The other was a mechanical duck that moved its wings and neck, ate grain from a bowl, and appeared to digest the food and excrete the remains.

This really caught the public imagination. Despite Vaucanson’s claims, the ‘digestion’ turned out to be an illusion. The grain was sucked through the mouth into a compartment inside the duck, but not digested. Instead, the excreted substance was released from a separate compartment. The mechanical ingenuity of Vaucanson’s automata was extraordinary. He went on to revolutionize silk manufacture in France, one of his innovations being a precursor of the automatic Jacquard loom, controlled by a chain of cardboard strips with punched holes. At the request of Louis XV, he tried to design and make a working model of the circulation of the blood, a project that, after many years, came to nothing. In the end, the defecating duck was Vaucanson’s best known achievement.

None of Vaucanson’s automata has survived, but we know that eighteenth century craftsmen were extremely skilled because of three astonishingly life-like figures made by Pierre Jaquet-Droz, his son, Henri-Louis, and Jean-Frédéric Leschot. These beautiful automata, first exhibited in 1774, survived, were restored to full working order, and can be seen today in Neuchatel: a young woman playing a keyboard organ, two children, a writer and a draughtsman. As with Vaucanson’s flute player, the organist’s fingers move across the keyboard and depress the keys to produce the notes. Depending which set of cams is deployed, The draughtsman draws one of four different drawings. Three cams control the arm movement: two move the pencil on the paper left to right, and up and down, and the third lifts the pencil from the surface. The figure also blows a puff of air from its lips to remove graphite dust from the paper. The writer is even more complex: he moves his head and eyes, dips a quill pen in the inkpot, shakes it to remove surplus ink and then writes a message of up to forty letters. A rotating disc with steel pegs arranged around the edge controls the deployment of the cams that produce the movements required for each letter. The pegs can be rearranged to change the message. Vaucanson’s automata had stood on large plinths which contained much of the mechanisms, but the Jaquet-Droz team miniaturized the components so that the whole mechanism fitted within the body of The writer.

The popularity of these automata encouraged many clock and watchmakers of the time to produce their own versions. Henri Maillardet, who had worked with Jaquet-Droz, exhibited a range of automata in London, including a draughtsman/writer that survived, and was restored to working order at the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia. The production of complex automata was much encouraged by a growing trade with China. The Chinese had a long tradition of increasingly complicated water clocks, with automated figures, but mechanically driven clockwork was new to them, so from the sixteenth century, the Chinese were really interested in acquiring clocks, and clockwork automata, from the West. During the eighteenth century increasingly complex and expensive machines were produced for this trade by such entrepreneurs as James Cox, whose museum of automata in London was briefly fashionable before the collection was sold by lottery in 1775, many of the pieces subsequently finding their way east.

In nineteenth century Europe the public appetite for automata continued to grow. Stage magicians such as Robert-Houdin and the Boulogne clockmaker Pierre Stevenard made some astonishing automata for their hugely popular stage performances.

New technologies and materials, and the beginnings of mass production, led to a wide range of smaller automata becoming available: some were still expensive playthings for the very rich, but other more affordable examples, including musical boxes, novelty clocks, mechanical figures and mechanical pictures, could be found in the ordinary bourgeois drawing room.

Towards the end of the century they could also be seen, on a rather larger scale, in the window displays of department stores.

A nineteenth-century print showing two of Jacques de Vaucanson’s androids, the Flute Player and the Pipe and Tambour Player on their large plinths.

Postage stamps illustrating two examples of the domestic scale automata produced in large numbers in nineteenth-century europe.

AUTOMATA IN THE EAST

There are very some early accounts of automata in China, such as the mechanical human figure said to have been made by Yan Shi for King Mu of the Zhou dynasty in the ninth century BCE. The account we have is from about 600 years later, and is clearly fanciful. There is also a legendary account of a South pointing chariot from around 2600BCE