Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mórula Editorial

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Eliana gave us a beautiful book, valuable beyond the biographical itinerary of its author, and with a quality that shouldn't be attributed only to its origins. But beyond a notable book, valuable in and of itself, Eliana gave us an extraordinary example of transgressing patterns, prejudices and probabilities. An admirable example of citizen self-invention.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 269

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Maré Testimonies

Eliana Sousa Silva

TRANSLATION

Sofia Soter

COPYEDITING

Rogério Amorim

AUTHOR PICTURE

Antonello Veneri

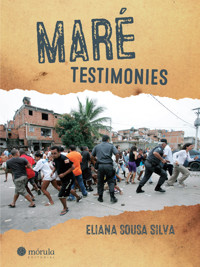

COVER PICTURE

Citizens riot because of the death of a child, Renan da Costa Ribeiro, in front of the 22nd Military Police Precinct on October 1st 2006 in the Nova Holanda favela, in Maré.

COVER PICTURE CREDITS

Marcelo Régua, Jornal O Dia

© 2016 MV Serviços e EditoraAll rights reserved.

R. Teotonio Regadas, 26 – 904 – Lapa – Rio de Janeiro – Brazilwww.morula.com.br • [email protected]

To Renan da Costa Ribeiro, a child who, like so many other childrenin hundreds of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, had his childhood cut short by violence we cannot accept.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To Jailson, for our unlimited love.

To João Aleixo Silva, Rodrigo Luiz and Paula Pimenta, expressions of unconditional love.

To my parents, João and Maria Aleixo, my four sisters and my brother, for lighting up my life.

To my nieces and nephews, for the love and energy we share.

To Heloisa Buarque de Hollanda, Luciana Bento, Gisele Martins, Ary Pimentel and Denise Peni, who were essential to the making of this book.

To André Urani, in memoriam, for the privilege of sharing his dreams and projects.

To the public security officials I met in this attempt to understand the actions of the Military Police in the favelas. It was a happy surprise to see that there are people who, like me, also want to go beyond their comfort zones and find a political and existential meaning in what they chose to do with their lives.

To everyone who shares the dream of creating a better life for those who live in Maré, acting through Redes da Maré. Here’s the proof of my gratitude to those who weave together this institution, partners in utopia, here and now.

To those who live in Maré, the reason for this work. Maré: where my life makes itself felt.

FOREWORD

Eliana Sousa Silva’s book, Maré Testimonies, is important for many reasons. First of all, the most evident: it produces relevant knowledge about the multidimensional complexity of public security and its strategic challenge – the relation between criminal justice institutions, especially law enforcement, and the Brazilian society, especially subaltern classes; a challenge that, in this instance, presents itself in its most delicate and demanding form, since the communities that make up Maré have lived a dramatic experience of geopolitical division, stemming from the bellicose rivalry between three criminal factions involved in the drug and arms trade.

Many poor neighborhoods in Rio face recurrent and institutionalized police brutality, resulting in a real genocide (from 2003 to 2010, 8,708 people were reported dead by police violence in the state of Rio de Janeiro), but Maré has also suffered the effects of the despotic presence and the occasional conflicts between armed groups that have been organized around the drug trade, allied with corrupt police segments, in an environment fostered by a hypocrite and irrational drugs policy.

At this point, I allow myself to interrupt my train of thought to consider that maybe some will find the use of the word “genocide” to describe the (still) ongoing process in Rio a little over the top. In this case, I ask the critical reader to read my emphatic tone against the backdrop offered by the following words, quoted in this book. Turned into song, they were repeated for many years as a sort of mantra in officer training in the Special Operations Police Force (Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais) of Rio de Janeiro’s Military Police (Polícia Militar), under the blessing of commands and governments and before an either indifferent or exulting public opinion:

An interrogation’s really easy to start / just beat the favelado until it hurts / an interrogation is really easy to end / just beat the favelado until he dies / you don’t clean up with a broom / you clean up with grenades / with rifles and machine guns.1

Am I exaggerating? Or are we really talking about institutionalized barbaric violence supporting a genocide? Allow me, now, to come back to my train of thought.

Without losing from obstacles and risk, and going against violence, community socialization has been practiced with intense vitality, showing once again that the favela isn’t an unilaterally negative space, defined by lack, emptiness, need and incompletion. It’s also a place for citizen creativity, in every area of human activity. This constructive social energy even manifests itself – as the author shows us – in organizing solutions to widely shared insecurity.

Therefore, the actions of armed factions and the regular police interventions don’t find a void, but the thickness of cultural and symbolic resistance and the density of social networks. The community throws itself at the demanding daily life, at the confrontations, at the unfortunate and terrifying visits of the Skull,at the inconsequential police operations, at the tyrant will of young dealers but also, thankfully, has moments of peace. Those who live in Maré don’t give in to skepticism and stillness. They persist: negotiating, mediating, reacting, anticipating, searching for the support of Rio’s society and of political representatives, beyond the neighborhood, to allow for the collective construction of alternative scenarios. The community acts unarmed, but gifted with the legitimate word, with the power of its multiple voices and with the force of popular organizations.

Still, it’s not idealized by the author as a single cohesive unit, beyond good and evil. Contradictions circle social life as in any territory, in any part of town. They also circle law enforcement and the drugs and arms trade. There are no simple and homogeneous realities in society. Therefore, generalizations won’t stand, neither the ones echoing accusations, nor the ones stamped on crime statistics. Eliana Sousa Silva teaches us that the stories of social groups are distinctive, the territories keep their secrets, the political and institutional webs carry their own conflicts and should be analyzed in their specificity, without losing sight, however, of the broader contexts and of state and federal (and even transnational) conjunctions, in the heart of which the peculiarity of each path gains full meaning.

How, then, can public security be treated as if it was a object unattached to its time and to the marks of history? How can it be treated as if independent from politics and culture, from economy and social structures, from expectations and dreams, from values and beliefs, from the affection and resentment of the men and women who, everyday, build social relations? It can’t, the author tells us. Not without paying a hefty price for being reductionist. A price that leads to a deficit in knowledge and to debt in prejudices.

That’s why her study on public security and violence in Maré, or from the point of view Maré, is first and foremost a clear and sensitive investigation on the history of the community, on the expansion of democracy in poor neighborhoods, on popular associations and their pitfalls, on electoral tactics and anti-manipulation strategies, and on the relationship with the State as mediated by the forces of law and order, reframed as instruments of disorder by their practice.

The use of interviews and statements, participant observation and the exchanges with police officers, drug dealers and civilians are so important that it’s featured in the title: “testimonies”. I’d even dare suggest that this book, originally a PhD thesis, was actually written in the fashion of a long testimony of the author herself. Like literature’s Bildungsromans, in the social sciences there are genealogical reports (explicitly or tacitly autobiographical) related to the author’s coming of age as human subjects, scholars and citizens; yet, such stories can still be relevant portraits of more general aspects of society.

It’s in this context that I place the work the reader has in their hands. And this is one more reason for the special importance I attribute to this book. Who else could be able to conduct a research listening to police officers, drug dealers and the people of a community where the two former groups tend to fight? Who could have the human authority and the social legitimacy to walk freely, deserving everyone’s respect? Who could obtain safe-conduct to cross war zones and borders separating enemy powers in the same territory? Who could gain enough trust to get precious testimonies, beyond the layer of (justified) fear? Who could overcome so bravely their own fear to walk among such different characters with poise?

There could only be one answer: someone who, as well as being a competent scholar, had lived all their life with these people, had grown up with their families, shared the pain and the pleasure of being part of the same. Someone who, by their actions through the decades, had shown, beyond all doubt, ethical rigor in the defense of their principles, complete loyalty to the community and unwavering openness to dialogue – balancing leadership and the humbleness of one who’s part of a brotherland. Someone whose word was deserving of trust and was worth as much as strong currency, unquestionable to every group, every character and every quadrant. Someone whose personal and political paths had made history and, in telling their life and remembering what happened, would be writing the story of their city and their generation. Someone like Eliana Sousa Silva.

Eliana grew up in Maré. She was the first female president of a neighborhood association. She attended college, studied abroad, got a PhD, without ever leaving Maré behind. She dedicated herself to social, cultural and educational projects. She invested in the creation of free night schools to prepare for college admissions, so that others could also have the chance that destiny hadn’t denied her. She led people in the fight for human rights and for change in the decades-old public security model – suspended or temporarily transformed for brief periods of time.

For all that and more, I believe we owe Eliana Sousa Silva much more than what could be said in a foreword. She gave us a beautiful book, valuable beyond the biographical itinerary of its author, and with a quality that shouldn’t be attributed only to its origins. But beyond a notable book, valuable in and of itself, Eliana gave us an extraordinary example of transgressing patterns, prejudices and probabilities. An admirable example of citizen self-invention.

LUIZ EDUARDO SOARES

ANTHROPOLOGIST AND WRITER

1 “O interrogatório é muito fácil de fazer / pega o favelado e dá porrada até doer / O interrogatório é muito fácil de acabar / pega o favelado e dá porrada até matar. Bandido favelado / não se varre com vassoura / se varre com granada / com fuzil, metralhador.”

CHAPTER 1

On elections, absurd deaths and new perspectives on violence in Maré

It was an intensely hot and sunny morning. Children played on the streets, running over political candidate flyers, distributed by canvassers and illegal campaigners. In the overpass above Avenida Brasil, a group of men and women handed people the flyers that were carried by the wind, as if a rain of democracy fell on the favela in this day, October 1st 2006, when another election for governor, senators and state and federal representatives happened around the country. According to the press, the electoral process went as planned by the electoral court, save a few hitches due to the particular realities of each state.

In the case of Rio de Janeiro, occasional incidents were reported in specific areas where the elections were taking place – especially in polling stations in favelas. In these areas, there is stronger law enforcement due to the alleged risk brought on by drug dealers or militias1 faced by voters and those responsible for the election.

In the Maré favela complex,2 election days are always festive moments, whether because of the sheer amount of people on the streets campaigning, or because of the opportunity to see old friends and family who moved to other neighborhoods but still vote at the same polling station. Without a doubt, the atmosphere on election days in the poorer, more stigmatized, areas of the city is characterized by the happiness of group encounters and by the persistent hint of hope that the political process might bring them a better life.

In practical terms, the election is also seen as a special and positive moment because a lot of people find temporary employment in canvassing, even if they rarely believe in the candidate’s proposals. In this specific territory, the electoral process is a very intense and agitated time, and its climax, the moment of ultimate celebration, is the first election, when voters go to the stations to choose their candidates.

For me, as someone who left Maré in 1995, election day is a personal civic ritual: I go back to the same polling station where I cast my first vote. I’ve never given up on this experience of coming back to my origins, and on the pleasure of feeling once more the intensity of living in this place, to which I’m still tethered by so many different personal bonds.

On October 1st 2006, however, the election meant something different for me. On this day, I watched a scene that moved me deeply and contributed decisively to the choice of theme for my PhD research, on which this book is based. A fact that wasn’t deemed worthy of press attention became essential to me, because it triggered a new way of perceiving reality and allowed me to realize how I could contribute to another form of law enforcement in the favelas, as well as making me rethink the effects of the public security intervention that’s been happening for a long time in these areas.

Like in every election, I was in front of my parents’ old home, in Nova Holanda, the area of Maré where I lived for 28 years. The house is across the street from the public school where I studied as a kid, that serves as an important polling station on election days.

It was half past noon when two police SUVs abruptly showed up on the main street of Nova Holanda. Even though there didn’t seem to be any problems around, the cars sped by, aimlessly shooting and burning rubber. People were gathered in the street: some of them talking, like me, some of them playing cards or having barbecues. Everyone got scared and ran for cover in nearby houses and stores.

I found cover in a drugstore and, from there, watched an awful scene: a three-year-old child, holding his grandmother’s hand, was hit by a bullet in the stomach as police officers shot without seeing where they were aiming.

The grandmother, who was running for cover when she heard the shots, started screaming when she saw the child fall to the ground. Upon realizing the child had been shot, one of the officers stopped his car, got out, and, with no comment or explanation, picked up the child and ran back to the car to, as I came to know later, take him to a nearby hospital. The grandmother, who had started feeling unwell a little earlier, fainted and was cared for by neighbors who came to her aid.

After the police went away, a significant number of people who watched what had happened went to the streets, yelling about the absurdity of it all and asking for justice. It was an atmosphere of commotion as people faced the weight of that act of violence. A feeling of rebellion rose in the voices of those who were there, and the decision to go to the 22nd Precinct – the only police station inside a favela in Rio, ironically placed 300 meters from where the shooting occurred – to protest against what happened was unanimous.

People were clearly upset, and some were getting violent. Noticing the growing turmoil, I approached them and proposed going to the station, in an orderly fashion, to ask for justice and demand that those responsible were punished. As we discussed what to do, we received the news that the child, whose name was Renan, had died soon after getting to the hospital. Once again, people got angry, and there were screams, accusations and expletives. The tumult was overwhelming and we started crossing the two blocks that separated us from the station.

Our arrival was disastrously received, a clear example of how law enforcement, despite being the State’s responsibility, is far from being a republican organization: a big gate at the back of the building was shut in our face.

The group’s first intent was to speak to the chief to explain, clearly and objectively, what had happened, as an attempt to contribute to the verification of facts. However, the chief took a long time to come to the gate, and more people kept arriving to protest. There were lots of insults all around: the people called the officers guarding the gate murderers; the officers looked at us with disgust and responded in kind, yelling, cursing and making rude remarks, especially directed to women. It was painful to wait for four hours in front of a police station and to feel so clearly the distance between the people of that community and the law enforcement officers.

As we waited to speak to the chief, we called professionals who worked in human rights organizations, such as Global Justice. After two of these experts arrived, we decided to form a commission and force our way into the station, since we hadn’t received an answer regarding that possibility yet. Faced with the new scenario, the chief finally decided to come to the gate and welcome a group of people in his office.

The group was composed of me, chosen by the people because of my long history of activism, the human rights institution representatives we had called, and one of Renan’s aunts. It was a very hard conversation due to the extremely defensive and guarded stance of the chief, who didn’t hide his discomfort in talking to us.

Right off the bat, when we tried to explain what we watched as the police arrived in Nova Holanda, we were met with a rude and aggressive response. The chief defended the officers without considering what we had to say, claiming they were there because they had seen two gun-carrying drug dealers on a motorcycle at the place of the shooting.

Hearing this argument, the boy’s aunt grew angry, emphatically declaring that that wasn’t what had transpired. In the opinion of some of the people there, the officers attacked in retaliation for local dealers’ refusal to comply with extortion, claiming they had already payed off another group of police officers not to be bothered that day.

What was most impressive to me was the chief’s insistence in ignoring any version of the facts other than the one told by his officers. He had no interest in listening to the people in the area, to the people he allegedly ought to protect. It was evident he wasn’t going to make any efforts to investigate the murder of a child, and that he saw the whole community as a threat.

Faced with these facts, we went back to the gate. The protesters got even angrier, and the cursing grew louder. After a few hours, the press arrived, deeply annoying the police officers. They tried to close the gate once more, but the protesters wouldn’t let them until they had gotten a clear position from the police. In that moment, there was some shoving. The officers threw tear gas bombs and shot into the air to disperse the crowd.

However, they didn’t accomplish their goal, and were met with more violence: some people started throwing rocks and pieces of wood at the station. As it turned into a riot, we ran for cover behind parked cars. I couldn’t help crying as I saw, disappointed, how such an expressive show of citizenship had been met with authoritarianism, violence and complete disregard for human beings. I was taken, then, by a sudden feeling of helplessness and disbelief, knowing that those actions weren’t an isolated incident, but a typical expression of how law enforcement acts in the poorer parts of town.

The next day, every newspaper in town talked about the disturbance during election day in Maré. The versions of the story presented by the press were many, all of them trying to justify the absurd and unnecessary death of Renan. The news mostly repeated the official version of the police: an alleged confrontation between police and drug dealers. As we had suspected, the case was closed and nothing happened to the officers involved.

This situation impacted my mind, my eyes and my soul – and to this day it follows me and feeds me. Trying not to succumb to the brutality, my initial feelings of disappointment, pain and helplessness were replaced by the drive to understand the reasoning behind the violence in the favelas and to look for alternatives.

Through permanent dialogue between different subjects, from different places and walks of life, I believe we can construct in the present what the people of Nova Holanda asked for in the commotion following Renan’s death: the end of police violence and a new public security policy based on the respect for the life of those who live in Rio’s favelas. That’s why, instead of demonizing the actions of law enforcement in the outskirts of town and in areas of affordable housing, I tried to get a better understanding of police intervention in Maré; in order to do that, I tried to create channels that would allow me to listen to the stories of law enforcement agents, as well as of the people of Maré – among them drug dealers and militiamen, important agents in the representations that, in the war logic that intends to defeat an enemy, justify lethal incursions into these spaces.

Considering the broadness of points of view and interpretations, I believe it can be possible to create a space for dialogue with an array of authors who propose different theoretical and practical concepts, all of them regarding the realization of a new policy of citizen safety. I believe this is not only possible but necessary to a significant improvement in quality of life in the favelas and throughout the city.

The direction of my journey

At seven years old, I moved to Nova Holanda, one of the favelas in the Maré neighborhood.3At the time, my life was restricted to going to school, to the Sagrada Família parish – the Catholic Church, into which I was raised, and a religion with which my parents are still greatly involved –, and to playing inside with my four sisters and my brother. My parents wouldn’t let us play on the street: “where you only learn the things you shouldn’t”, they said with the strictness of northeasterns who were raised according to very different rules than those seen in the favela. With the streets a forbidden space, my parents took us to the movies and to amusement parks when they could.

As a teenager, I started helping my parents in their store, a bodega at the corner of the main street and Sargento Silva Nunes. The store was the family’s main source of income. At that point, my knowledge about the area where we lived was still very limited, and all my friends were from school or from church. In my life, there was no time to frequent neighbor’s houses or other places in the community (nor would my parents allow it). Therefore, up until that moment, my experience in the favela was marked by clear limits around home, school and church, restricting my range of experiences and relationships to my family and to institutions. My reality as someone who lived in the favela was, in many ways, very different from that of most people, in particular teenagers, who experienced the rich possibilities of public space and popular culture in the favela.

I was aware of this difference, and it made me extremely curious about the experiences of my neighbors and school friends. I was especially moved by the question of violence, that was already very present in the daily life of the people of the favela, both in reality and in the collective imagination that was being created at the time. We lived across the street from a DPO (Destacamento de Policiamento Ostensivo), a Military Police detachment installed in a small building on main street to act on the favela. At the time, I saw many boys – and some girls – arrested and sometimes beaten up by the police. There was so much screaming and name-calling that sometimes we couldn’t even sleep. However, back then, I didn’t understand why people were being arrested, why they were assaulted, or why there was so much tension and disrespect between the people and the police.

Furthermore, I found it weird and somewhat appalling that many basic services weren’t being provided in Nova Holanda, such as drinking water or waste disposal, as well as electricity, schools, preschools and entertainment areas. One of the only ways the State made itself known in the region was through police violence. However, in the instance of public security, the service that was provided to us was characterized by abuse of power, corruption and the violation of people’s rights coming from part of those who represented the State.

I started getting involved in community projects from a young age. At first through the Catholic Church, then through other community organizations, such as the neighborhood associations and the Favela Federation (Federação de Favelas do Rio de Janeiro), or through extension projects linked to the health institution Fiocruz (Fundação Oswaldo Cruz). These practices allowed me to make direct contact with situations of extreme poverty and with the social problems inherent to life in Nova Holanda and other similar areas.

In 1984, right after turning 22, I ran for president of Nova Holanda’s neighborhood association as part of the Pink Slate, a color that represented women’s roles in the community and as a spearheading figure in local claims. It was an unforgettable electoral process: the first direct election in the community, allowing people to fulfill their role as subjects of their own stories. Until then, the Lion XIII Foundation (Fundação Leão XIII), a branch of the state’s Social Action Office (Secretaria da Ação Social), had been responsible for choosing the institution’s directors.

The election was marked by massive participation of the people of the favela, and by the hope that many changes would follow, because people were trying to guarantee their rights through collective action. In this environment of hope, faith and joy, we won the election by a large margin of votes.

For the next eight years I was part of the neighborhood association, with a participation marked by strong popular mobilization. The process, inserted in the context of the country’s democratization and of more openness to popular demands from state and municipal governments, accounted for the achievement of most of the basic services that are currently provided to Nova Holanda.

Even back then, violence and the social order of the favela were excluded from the public debate in local organizations. At most, there were occasional movements against extreme police brutality.

This experience with community activism was intense and determinant to my life. It was through it that I understood the complexity of my place, of the favelas and of the city as a whole. In this process, I saw myself, in the mid-90s, devoted to a new way of acting in Maré, considering not only the reality and the problems of Nova Holanda, but the whole group of 16 favelas, and working with what I define as second and third generation demands.4

In 1997, alongside a group of locals and ex-locals, I participated in the creation of a social organization called, at the time, CEASM (Maré Center of Studies and Solidarity Actions – Centro de Estudos e Ações Solidárias da Maré). As the president of the organization for ten years, I could develop a series of projects aiming to broaden existential possibilities, especially those of teenagers and young adults of Maré. Afterwards, I was part of the creation of another social organization, with the objective to act in the city, the Rio Favela Observatory (Observatório de Favelas do Rio de Janeiro). But the desire to act in a way that would create institutional structural changes in Maré was still strong in me. That’s why, in 2007, we created the Maré Development Network (Redes de Desenvolvimento da Maré), Redes for short, the successor to the late CEASM.

In the process of intervening in local reality, we started to run into the question of violence more frequently. The confrontations between young drug dealers and police officers were common, so there was the permanent need to negotiate with both groups, as to avoid conflicts that would expose students and to restrain arbitrary actions, especially from the police force.

Because of that, it became clear to me that it wouldn’t be possible to consider better life quality in the favela without trying to create new positions and propositions regarding violence, which became the main problem of Brazilian urban centers in the late 20th century, especially to the people who lived in favelas. To attain this goal, I needed to broaden my understanding of urban social reality and intervention to beyond the borders of Maré. With this desire and this objective, I built the study that took shape as this book.

A preliminary question in the proposed investigation was to understand how the knowledge and the experience I’d gained from my studies and social trajectory could contribute to the production of new perceptions and approaches to the social space of the favela and its population. This was necessary because I’d long been aware of the lack of academic investigations into the subject at hand written by people with similar trajectories to mine.

With this affirmation, I don’t want to endorse purist and sectarian judgements, based on the assumption that only subjects of poor origins, as well as from other subaltern groups in the present social order, can speak or write about their practices. On the contrary, I understand the need for a plurality of points of view regarding the lives and practices in the social world, in all its levels. This includes, necessarily, scholars from the favelas and from the outskirts of town. However, a subject’s perspective on their world and social reality in these social spaces is still lacking in Rio’s academia (the same could be said for Brazilian academia as a whole).

In this study, the attempt to intertwine my political and academic interests makes itself clear. In this tension, I develop a study marked by the choice – if I can, with such a rational word, name something so visceral – to act as an insider scholar in the social space of the favela. In other words, this is the work of someone who lives, analyzes, influences and is influenced by the territory and the theme of the study. I’m also legitimized as an author because of my path, my historical insertion in Maré and my objective and direct experience with violent practices and their solid effects in the locale, in the city, in my personal existence. This composite of experiences, reflections and analysis is what the reader will find in the book that’s now in your hands.

Through the lens of personal experience, I attempted to develop reflections brought by the analysis of the context of law enforcement practices in Maré. In this work, I point out many questions that seem to be relevant to give proper dimension to the phenomenon of violence and public security. In the first place, a very important aspect of this study was the contact with police officers from the Maré precinct and with other subjects of armed violence in regions ruled by criminal organizations, such as drug dealers and militias.

Therefore, I could deal with the three central actors involved in the issue of violence in a new way, and better understand their actions – which doesn’t mean, of course, that I justify them. In the interview process, I could also better understand the perceptions of my interviewees, whether they were civilians, armed criminals or police officers, which allowed me to humanize these characters and to deconstruct the demonized figures that were cemented in our brains after being circulated and reproduced by corporate media. In this way, it was possible to understand the structural aspect of the issue of violence, the suffering of all those involved and the limits of current public security strategies.

1