13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

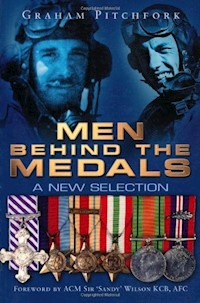

Of the many characteristics that emerge in warfare, none generates more admiration than gallantry. Using medal groups chosen for their unique combinations of gallantry and campaign awards, Graham Pitchfork pays tribute to the bravery of twenty Allied airmen who flew combat operations during the Second World War. Encompassing a wide cross-section of operational roles, theatres, aircraft types and aircrew categories, the men behind the medals' experiences and actions are narrated in relation to the wider war. These crucial operations are seen through a variety of different actions, including a night-fighter crew and a navigator who took part in supply drops to Resistance movements. The air war at sea is seen through the experiences of a Beaufighter pilot and a Royal Navy observer who attacked the Italian Fleet at Taranto. As the Second World War generation fade into history, their exploits need to live on forever as an example for future generations. In describing the exploits of the lesser-known heroes of that air war, Graham Pitchfork has ensured that 'The Many' will never be forgotten.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

MENBEHIND THE MEDALS

MENBEHIND THE MEDALS

A NEW SELECTION

AIR COMMODORE GRAHAM PITCHFORK

First published in 2003

This edition first published in 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Graham Pitchfork, 2003, 2009, 2013

The right of Graham Pitchfork to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9991 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Preface

1

The Medals

2

Daylight Attacker

3

Taranto Observer

4

Millennium Evader

5

Bomber Squadron Commander

6

Torpedo Attack Pilot

7

Jungle Hurricane Pilot

8

Malta Blenheim Navigator

9

Escape from Italy

10

Stirling Engineer

11

Over Madagascar and Italy

12

Spitfires to Moonlighting

13

Supplying the Partisans

14

Light Night Striking Force

15

Aegean Sea Strike Pilot

16

Night Fighter Radar Ace

17

Halton ‘Brat’ at Sea

18

Photographic Reconnaissance Navigator

19

Artillery Spotter Pilot

20

Rocket Typhoon Pilot

21

Low-Level Fighter Reconnaissance

Bibliography

Foreword

Air Chief Marshal Sir ‘Sandy’ Wilson KCB, AFC

If I were asked what characteristics most personified the generation that fought in the Second World War, like many others, I am sure, I would have to say that bravery and modesty were uppermost. Certainly, these characteristics are to be found in ample measure in this fascinating book.

Those of us who served in the Armed Forces in the aftermath of that war were privileged to know and fly with many gallant aircrew who had served with such distinction during those times. Although we thought we knew them well, and notwithstanding how distinguished they were, it was often not until we read their obituaries in our national newspapers that we gained any real appreciation of their service and heroism. Even then, one is often left wondering how much more could have been said. This was brought home to me when I was asked by the family of one of the most famous of all wartime aircrew, Flight Lieutenant Bill Reid VC, to give an address at his funeral. Whilst the epic story of how he won his supreme award has been widely told, it was only when I began to research the rest of his wartime service that I realised how much more there was to record.

As President of the Aircrew Association, I have been privileged to meet many of that modest wartime generation, and to hear at first hand their truly amazing untold stories. I have often asked them why they had not recorded their experiences for the benefit of future generations. Almost always, they reply, ‘But I did no more than countless others – and would anyone be interested in my experiences anyway?’ My instant reply has always been an emphatic ‘Of course they would!’

Having said that, it has to be added that it takes the professional skill of an airmen with an acute eye for history to bring such stories properly to life. In this, his second volume of Men Behind the Medals, Air Commodore Graham Pitchfork has done just that and, once again, has brought these incredible stories to light before it is too late. In this volume he has gone further by including many roles and theatres not covered in his previous book, and it is particularly appropriate that he has included aircrew who served in the Fleet Air Arm and the Army, as well as one story featuring that loyal and dedicated band of RAF ground crew.

As we have come to expect, Air Commodore Pitchfork has researched this book meticulously, and it is enhanced by the many illustrations and photographs never before published – many provided by the individuals and their families. The book makes a very valuable and important contribution to our aviation history. Above all, these stories, which personify the grit, gallantry and sense of duty of this modest era of aircrew, should serve as an example to both present and future generations.

Sandy Wilson

Stow-on-the-Wold

Acknowledgements

Writing this book about gallant aircrew has been a particularly rewarding task, but it could not have been completed without a great deal of help from many people. Their patience, support, expert advice and friendship have allowed me to complete this second volume; I am extremely grateful and wish to thank all of them. I would particularly like to thank my friend of over forty years, Air Chief Marshal Sir ‘Sandy’ Wilson for his support and for his generous Foreword. As the President of the Aircrew Association, no one is more qualified to appreciate the exploits of the men whose stories appear in this book.

The Director of the Air Historical Branch, Sebastian Cox, and his excellent staff have given me a great deal of assistance, none more so than Graham Day. The staffs of the Public Record Office have also been most helpful. Ken Delve of Key Publishing and Ken Ellis, the editor of Flypast magazine, have given a great deal of advice, and I am grateful to both for their continued support of my series ‘Men Behind the Medals’ in their excellent magazine. I am very grateful that they have agreed to continue with the series after the publication of this book. Group Captain Chris Morris has proofread every chapter as it has been completed, and his expert advice has been invaluable. Wing Commander Jim Routledge has, once again, given his expert advice on medals. Paul Baillie, John Foreman and Mike King have given me valuable assistance, and I thank Jimmie Taylor for allowing me to use some of his research material for the Arnhem operation.

Photographs are a key component of this book and I want to thank my old friends Peter Green, Andy Thomas and Chris Ashworth for the loan of photographs, and for their advice and help on many aspects. I thank Paul Johnson at the Public Record Office, Flight Lieutenant Mary Hudson at the Air Historical Branch, and the staff of the Imperial War Museum for their help and for permission to use copyright photographs. Many others helped with individual photographs, and I hope they will accept the individual acknowledgements as my thanks for their help.

I am particularly grateful to Lady Lawrence, Mrs Ann Evans, Mrs Irene Neale and Mrs Estelle Wright for allowing me access to their late husbands’ logbooks, papers and photograph albums. Also Nicholas Webb who loaned me a great deal of material relating to his late grandfather, and to Jennie McIntosh for help with material relating to her late father, John Neale, who died during the preparation of this book. I reserve a very special thank-you to members of the Aircrew Association, other former aircrew who have given valuable advice, and to some of the ‘Men’ who appear in this book. In particular, I want to single out the following who entertained me in their homes, gave valuable information and advice and could not have been more helpful and kind: Frank Bayliss AFM, the late Ken Brain DFC, Dudley Burnside DSO, OBE, DFC and Bar, John Cruikshank VC, Derek Smith DFC and Bar, Freddie Deeks DFC, Lionel Daffurn DFC, David Ellis DFC, Guy Fazan DFC, Terry Goodwin DFC, DFM, Arthur Hall DFC and Bar, Bob Large DFC, Derek Manley, Roy Marlow MM, the late John Neale DSC, DFC, Doug Nicholls DFC, Charles Patterson DSO, DFC, Tom Pratt DFC, Joe Reed DFC, the late Bill Reid VC, Denys Stanley MBE, DFC, Jack Strain DFM, Joe Townshend DFM, David Urry, the late Aubrey Young DFC.

Finally, I want to thank the staff of Sutton Publishing for all their support, in particular Jonathan Falconer, Nick Reynolds, Elizabeth Stone and Bow Watkinson.

Preface

The chapters that follow relate the stories of twenty gallant young men who flew on operations during the Second World War. Their particular stories have been selected in order to embrace a wide cross-section of the flying operations conducted, in the main, by the Royal Air Force. However, in recognition of the significant contributions made by aircrew serving in the Fleet Air Arm and the British Army, I have included a chapter devoted to a man from each of these services. I have tried to embrace as many different roles and theatres of operations as possible, but not all can be included. Some were covered in volume one of Men Behind the Medals, and some omitted from the earlier book have been included in this volume, making, I trust, a very wide and comprehensive range across the two volumes.

I have endeavoured to include as many different aircrew categories as possible, and also to include a wide example of the decorations awarded for gallantry in the air. Inevitably in a book limited to twenty accounts, there are a number of omissions, and I consciously decided not to include accounts of Victoria Cross holders since their amazing experiences have been covered in numerous other publications. I have not included the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, although the story of Sergeant Stuart Sloan CGM is covered in volume one. As in that volume, it has been my intention that each story stands on its own as a comprehensive account of an individual’s flying career, and this has caused a certain degree of overlap. For example, two of the ‘Men behind the Medals’ took part in bombing operations over North Africa, and two others took part in the first One Thousand Bomber Raid on Cologne. In other respects their stories are very different, and they would have been incomplete if I had abbreviated them on the basis that details had appeared in an earlier chapter.

Despite many years researching the history of the air war of 1939 to 1945, I continue to be amazed at the variety of roles, activities and the sheer scale of the air operations. One thing, however, remains constant, and transcends every other aspect – the determination, comradeship, gallantry and raw courage of a generation of young men who fought for our freedom. Sadly, they are now fading into history, but their exploits need to live on forever as a stimulus and example for future generations. They should never be forgotten, and, as in Volume One, I dedicate this book to ‘the Many.’

Chapter One

The Medals

Introduction

This book tells the story of the exploits and service of gallant aircrew from all three British services whose courage was recognised by the award of medals for service during the Second World War. Some general knowledge of the medals referred to in the chapters that follow would, I believe, provide some useful and interesting background. However, it is not the intention to treat the reader to a detailed study of British medals. This is a vast and fascinating topic and there are some outstanding works that the enthusiast can study; none more so than British Gallantry Awards by Abbott and Tamplin and British Battles and Medals by Gordon, both of which are strongly recommended.

The medals that appear in this book can be split into four categories: gallantry, campaign service, long service and commemorative. This chapter will concentrate on the background to the medals awarded to British and Commonwealth aircrew for gallantry and for service in the Second World War.

Readers should be aware that major changes were made to the Honours system in 1993, and some well-known gallantry medals have disappeared – for example, the Distinguished Flying Medal. Others, such as the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross, have been introduced. Since all the stories covered in this book relate to the Second World War, these changes will not be discussed in this chapter, and all reference to medals will be based on the pre-1993 changes.

The exploits of those awarded the Victoria Cross, the nation’s ultimate award for gallantry, have been researched and related in great detail and thus, I have chosen not to include a story of one of the recipients. To those with a specific interest in this award to airmen, I strongly recommend they read the eminent air historian Chaz Bowyer’s For Valour. The Air VCs.

The descriptions outlined below are general and do not go into the numerous warrants, minor changes and styles of naming that have been made over the years. Clearly, all the awards reflect the appropriate cypher and crown, but this book is concerned only with those awarded during the reigns of His Majesty King George VI and Queen Elizabeth II. The gallantry medals that appear in the following chapters are listed in order of precedence.

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire

This order was founded by King George V in June 1917 for services to the Empire. A military division was created in December 1918 with awards made to commissioned and warrant officers for distinguished services of a non-combatant character. The order consists of five classes and a medal. The insignia of the civil and military divisions is identical, but distinguished by their respective ribbons. In both cases, the ribbon is rose pink edged with pearl grey; the military division has a narrow central stripe, also in pearl grey. An example of the fourth order (officer) is included in this book.

Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) was instituted in 1886 and is only awarded to commissioned officers. It is available to members of all three services for ‘distinguished services under fire’, which might include a specific act of gallantry or distinguished service over a period of time. A good example of the former was the immediate award made to the then Pilot Officer Leonard Cheshire for safely bringing back to base his Whitley bomber of 102 Squadron, which had been severely damaged by enemy fire over Cologne.

The silver-gilt and white enamelled cross with the crown on the obverse and the cypher on the reverse hangs from a laurelled suspender and a red ribbon with narrow blue borders, which is attached to a similar laurelled bar and brooch. The year of award is engraved on the back of the suspender. Bars are awarded for subsequent acts of distinguished service or gallantry and these are similar in design to the brooch and suspender bars.

Some 870 orders and 72 bars were awarded to members of the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. A further 217 orders and 13 bars were awarded to members of the Commonwealth Air Forces and a further 38 Honorary Awards to foreign (non-Commonwealth) officers.

Distinguished Service Cross

The Conspicuous Service Cross, later to become the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), was instituted in June 1901, primarily to be awarded to warrant officers or subordinate officers of the Royal Navy for meritorious or distinguished service in action. On 14 October 1914 it was re-designated the ‘Distinguished Service Cross’ when the eligibility was extended to officers below the rank of Lieutenant Commander. Subsequently, further Orders in Council were made, which extended the eligibility to other forces. This included, from 17 April 1940, officers and warrant officers of the Royal Air Force serving with the Fleet.

The plain cross with rounded ends has the crowned royal cypher on the obverse, and the plain reverse is hallmarked with the date of issue engraved on the lower limb. The cross is attached to the ribbon, of three equal parts of dark blue, white and dark blue, by a silver ring passing through a smaller ring fixed to the top of the cross. Bars are awarded for further acts of gallantry and the year of award is engraved on the reverse.

Distinguished Flying Cross

Following the formation of an independent Royal Air Force on 1 April 1918, specific awards for gallantry in the air were instituted on 3 June 1918. This included the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) awarded to officers and warrant officers ‘for exceptional valour, courage and devotion to duty while flying in active operations against the enemy’. The award was extended to equivalent ranks in the Royal Navy on 11 March 1941.

The silver cross flory is surmounted by another cross of aeroplane propellers with a centre roundel within a wreath of laurels with an imperial crown and the letters RAF. The reverse is plain with the royal cypher above the date 1918. The cross is attached to the ribbon by a clasp adorned with two sprigs of laurel. Since July 1919 the ribbon has been violet and white alternate stripes running at an angle of forty-five degrees from left to right. The year of award is engraved on the reverse. Bars are awarded for further acts of gallantry and the year of award is engraved in a similar fashion.

During the Second World War just over 20,000 awards were made with a further 1,592 bars. Among the latter were forty-two second bars. Officers of the Royal Artillery engaged in flying duties during 1944 and 1945 were awarded eighty-seven crosses: the exploits of one of these officers, Captain A. Young, are described in a later chapter.

Air Force Cross

The Air Force Cross (AFC) was introduced at the same time as the DFC. It too is awarded to officers and warrant officers for an act or acts of valour, courage and devotion to duty while flying, though not in active service against the enemy.

The cross is silver and consists of a thunderbolt in the form of a cross, the arms conjoined by wings, the base bar terminating with a bomb surmounted by another cross composed of aeroplane propellers, the four ends inscribed with the letters GVRI. The roundel in the centre represents Hermes mounted on a hawk in flight bestowing a wreath. The reverse is plain with the royal cypher above the date 1918. The date of the award is engraved on the reverse. The suspension is a straight silver bar ornamented with sprigs of laurel. The ribbon is in the same style as the DFC with red and white diagonal stripes. Bars are awarded for further acts of gallantry or duty.

Distinguished Service Medal

The Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) was instituted in October 1914 for ‘courageous service in war’ by chief petty officers, petty officers and men of the Royal Navy, and non-commissioned officers and men of the Royal Marines. An additional Order in Council on 17 April 1940 made provision for the DSM to be awarded to NCOs and men of the Royal Air Force serving with the Fleet. On 13 January 1943, this was further extended to include service afloat yet not with the Fleet, such as air-sea rescue. Just twenty-three were awarded to members of the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. This Royal Navy medal is included here because a later chapter will relate the career of Flight Sergeant A.J. Brett RAF who was awarded the medal at the end of the Second World War.

The obverse of the circular silver medal carries the Sovereign’s effigy. The reverse carries a crowned wreath inscribed ‘FOR DISTINGUISHED SERVICE’. The medal is suspended from a straight suspender hanging from a ribbon of dark blue with two white stripes towards the centre. The medal is named on the edge. Bars are awarded for subsequent acts of valour.

Military Medal

Although the Military Medal (MM) is not awarded for flying operations, a number of awards have been made for gallantry to members of the Royal Air Force and the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. A brief description is included here since a later chapter will relate the story of Warrant Officer R. Marlow, who was awarded the medal in 1945.

The medal is awarded to non-commissioned officers and men of the British Army for bravery in the field. It was instituted in 1916 and extended by a 1920 warrant to include other ranks of ‘any of Our Military Forces’. A warrant in 1931 refined this statement further with a new provision that it could be given to other ranks of ‘Our Air Forces’ for services on the ground.

The silver medal carries the sovereign’s effigy on the obverse and the words ‘For Bravery in the Field’ surrounded by a laurel wreath surmounted by the royal cypher and a crown on the reverse. The medal is suspended by an ornate scroll bar suspender hanging from a dark blue ribbon with three white and two crimson narrow stripes down the centre. The medal is named on the edge with the recipient’s number, rank, name and unit.

During the Second World War 129 medals were awarded to the Air Forces including six to members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. Surprisingly, some medals were awarded to Royal Air Force personnel for engagements at sea.

Distinguished Flying Medal

The Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) was instituted at the same time as the DFC and is awarded to non-commissioned officers and other ranks for ‘an act or acts of valour, courage or devotion to duty performed while flying in operations against the enemy’.

The silver medal is oval shaped and carries the sovereign’s effigy. The reverse is more ornate showing Athena Nike seated on an aeroplane with a hawk rising from her right hand. Below are the words FOR COURAGE and the George VI issue contain the date 1918 in the top left-hand segment. The medal is suspended by a straight silver suspender fashioned in the form of two wings, all hanging from a ribbon of very narrow violet and white stripes at an angle of 45° from left to right. The medal is named on the edge. Bars are awarded for subsequent acts of valour and the date is engraved on the reverse.

During the Second World War 6,637 medals were awarded with just 60 bars and one second bar (the latter to Flight Sergeant Don Kingaby, who was later commissioned and awarded the DSO and AFC also). The small number of awards of the bar is explained since many recipients of the DFM were subsequently commissioned. Many were decorated again as officers.

Air Force Medal

The Air Force Medal (AFM) was the fourth of the ‘flying’ medals to be instituted by the Warrant on 3 June 1918 following the formation of the Royal Air Force. As with the AFC, the AFM is awarded for ‘valour, courage, or devotion to duty performed while flying not in active operations against the enemy’. The medal is awarded to non-commissioned officers and other ranks.

The silver medal is very similar to the DFM with the exception of the reverse and the ribbon. The reverse shows Hermes mounted on a hawk and bestowing a wreath. The George VI issue has the date 1918 placed at the centre left. The ribbon is the same design as the DFM but with the colours of red and white. The medals are named on the edge. Bars are awarded for additional acts of valour or duty.

There have been about 850 awards of the AFM since the award was instituted almost eighty years ago. Of these, 259 were awarded in the Second World War including two to the Army Air Corps. The AFM is the second most rare of the awards for flying.

Mention in Despatches

The practice of mentioning subordinates in despatches is of long standing. During the Second World War, and in recent years, a Mention in Despatches was normally awarded only for acts of gallantry or distinguished services in operations against the enemy for services that fell just short of the award of a gallantry medal. Until recently, the only medal to be awarded posthumously was the Victoria Cross. Posthumous ‘Mentions’ invariably indicated that the recipient would have earned a gallantry award had he survived, but, with the exception of the Victoria Cross, the statutes of the day denied posthumous recognition.

The emblem is single-leaved being approximately three-quarters of an inch long. For the Second World War the emblem is worn on the ribbon of the War Medal and for other actions it is worn on the appropriate campaign medal ribbon. Recommendations are submitted for the sovereign’s approval and a certificate is issued.

Air Efficiency Award

The Air Efficiency Award is not a gallantry award but is included here because it is an award made specifically to members of the Royal Air Force’s Auxiliary and Volunteer Reserve Forces. It was instituted in 1942 and can be awarded to all ranks who have completed ten years of service. War service reduced the qualifying period depending on the type of service.

The silver medal is oval with the sovereign’s effigy on the obverse. The reverse is plain with the words ‘AIR EFFICIENCY AWARD’. The suspender is an eagle with wings outspread and the medal hangs from a green ribbon with two pale blue central stripes. Bars can be awarded for additional service. The medal is named on the edge.

Efficiency Medal (Territorial)

The Efficiency Medal is similar to the Air Efficiency Award described above, but was awarded to other ranks of Army volunteer forces for twelve years’ service. Wartime service was counted as double value. A brief description is given because a later chapter includes the details of the service of Squadron Leader J. Harris, who commenced his military service in the Territorial Army before joining the Royal Air Force.

The oval silver medal has the monarch’s effigy on the obverse and the plain reverse is inscribed ‘FOR EFFICIENT SERVICE’. There is a fixed suspender bar decorated with a pair of silver palm leaves surmounted by a scroll inscribed ‘TERRITORIAL. The ribbon is green with yellow edges. The medal is named on the edge.

Second World War Campaign Stars and Medals

Eight campaign stars were awarded for services during the Second World War. The six-pointed stars were made of a copper zinc alloy and were identical except for the name of the campaign in an outer circle surrounding the royal cypher and crown. All the medals were issued un-named. The maximum number of stars that could be awarded to one individual was five. Nine clasps were issued but only one could be worn with each star.

The qualifying periods for the campaign stars vary greatly and the reader who wishes to verify specific awards should consult one of the authoritative books mentioned in the introduction to this chapter.

The 1939–45 Star. This star was awarded for service in an operational area between 3 September 1939 and 2 September 1945. The colours of the ribbon represents the three services with the navy blue of the Senior Service on the left, the red of the Army in the centre and the pale blue of the RAF on the right. Fighter aircrew that took part in the Battle of Britain between 10 July and 31 October 1940 were awarded the clasp ‘Battle of Britain’.

The Atlantic Star. The Atlantic Star was awarded to those involved in operations during the Battle of the Atlantic from 3 September 1940 to 8 May 1945. The watered ribbon of blue, white and green represents the mood of the Atlantic. The clasps ‘Aircrew Europe’ and ‘France and Germany’ can be worn with this star.

The Air Crew Europe Star. The Aircrew Europe Star was awarded for operational flying over Europe from airfields in the United Kingdom between the outbreak of war and the invasion of Normandy on 6 June 1944. The ribbon of ‘Air Force’ blue, with black edges and two yellow stripes represents continuous operations by day and night. The clasps ‘Atlantic’ and ‘France and Germany’ were awarded with this star.

The Africa Star. This star was awarded for one or more day’s service in numerous areas of Africa, primarily North Africa, between the entry of Italy in the war on 10 June 1940 and 12 May 1943. Other qualifying areas included Abyssinia, Somaliland, Sudan and Malta. The ribbon is a pale buff representing the desert with a central red stripe flanked by a single navy blue and light blue stripe. These represent the three services. The clasp ‘North Africa 1942–43’ was awarded to qualifying members of the RAF.

The Pacific Star. The Pacific Star was awarded for service in the Pacific area of operations between 8 December 1941 and 2 September 1945. These areas included those invaded by the enemy, Malaya and the Pacific Ocean. The ribbon is dark green with red edges with a central yellow stripe flanked by thin lines of dark and light blue. These colours represent the jungle and desert and the involvement of all three services. The clasp ‘Burma’ was issued with this star.

The Burma Star. This star was awarded for service in the Burma Campaign between 11 December 1941 and 2 September 1945 and for service in parts of India, China and Malaya over certain periods. The ribbon is dark blue with a wide red stripe down the middle. The latter represents the Commonwealth forces. The blue edges each have a central orange stripe representing the sun. Those eligible for both wore a clasp ‘Pacific’ with this star.

The Italy Star. This star was awarded from the beginning of the Italian campaign for operational service in Sicily or Italy from 11 June 1943 to 8 May 1945. Aircrew service between these dates over Yugoslavia, Greece, the Dodecanese, Sardinia and Corsica also qualified for this star. The ribbon represents the Italian colours of green, white and red in equal stripes with the green on the outside and the red in the middle of the white centre. There are no clasps with this star.

The France and Germany Star. This star was awarded for service in France, Belgium, Holland and Germany after D-Day on 6 June 1944 to VE Day on 8 May 1945. Operations mounted from Italy did not qualify for this star. The ribbon is red, white and blue representing the national flags of Great Britain, France and Holland. The colours are in equal stripes with the blue on the outside and the red in the centre. The clasp ‘Atlantic’ can be awarded with this star.

The Defence Medal. The Defence Medal is made of cupro-nickel and shows the uncrowned head of King George VI on the obverse. The reverse has the royal crown resting on the stump of an oak tree with the years 1939 and 1945 at the top left and right. The words ‘THE DEFENCE MEDAL are at the base. The ribbon is flame coloured with green edges and two thin black stripes down the centre of the green ones. These colours represent our green land and the fires during the night blitz. Qualification for this medal is complex but it was basically issued to reward those in a non-operational but threatened area and the qualifying period was three years at home and one year in certain areas overseas. The medal was issued un-named.

The War Medal. The medal is also made of cupro-nickel but the obverse has the crowned head of King George VI. The obverse shows a lion standing on a dragon with two heads with the years 1939 and 1945 above. The colours are symbolic of the Union Jack. All personnel with a minimum of twenty-eight day’ service were eligible for the award. The War Medal was also issued un-named.

Campaign Medals

Since the early nineteenth century medals have been awarded to those who have taken part in the countless campaigns that have involved British forces overseas. Where there may have been numerous actions within a campaign, individual clasps have been awarded which are attached to the ribbon of the campaign medal. For example, during the early part of the twentieth century there were numerous actions in the North of India and a total of twelve clasps were awarded for the Indian General Service Medal. There are very many British campaign medals, but the reader will only encounter the General Service Medal in the chapters below, and so a brief description follows.

General Service Medal. To commemorate other ‘minor’ wars following the end of the First World War a General Service Medal was instituted in 1923, and by the time it was replaced in 1962 sixteen clasps had been authorised. Some will be covered in the stories that follow. The medal has been issued with three different obverse effigies and several different legends. The crowned head of the sovereign appears on the obverse. On the reverse is the standing winged figure of Victory holding a trident and who is placing a wreath on the emblems of the two services. The ornamental suspender and the medal hang from a purple ribbon with a central green stripe. The recipient’s name is impressed on the edge. Recipients of a Mention in Despatches wear a bronze oak leaf emblem on the ribbon.

Royal Air Force Long Service & Good Conduct Medal

The RAF’s Long Service and Good Conduct Medal (LS&GC) was instituted on 1 July 1919, and awarded to non-commissioned officers and other ranks of the RAF for eighteen years’ exemplary service. (This was reduced to fifteen years in 1977.) In 1947 officers who had served for twelve years in the ranks became eligible for the medal. A bar is awarded for further similar periods of service.

The obverse of the silver medal carries the effigy of the sovereign, and the reverse has the RAF eagle and crown insignia surrounded by the words ‘FOR LONG SERVICE AND GOOD CONDUCT’. The medal is named on the edge.

Chapter Two

Daylight Attacker – Charles Patterson

With war imminent, nineteen-year-old Charles Patterson returned from his farming studies in Ireland to join the Royal Air Force as a pilot. He commenced his training in November 1939 and was soon offered a commission. On completion of a basic aircrew course at 5 Initial Training Wing, based in a Hastings hotel, he left to begin pilot training on Tiger Moths at 12 Elementary Flying Training School at Prestwick. Patterson was allocated to nineteen-year-old instructor Sergeant Elder, and made his first flight in N 9430 on 18 June 1940 and completed his first solo after ten hours of dual instruction. Barely six weeks later he had completed the elementary course with forty-six hours recorded in his logbook and an above average assessment.

The next stage of training was at 2 Flying Training School at Brize Norton, and Patterson flew his first sortie in an Oxford (R 6317) with Flight Lieutenant de Sarigny on 6 August 1940. The young trainee pilots were suddenly introduced to the reality of war on 16 August when two Junkers 88 bombers wrought tremendous havoc on the airfield over a period of a few minutes. Two hangars full of Oxford aircraft were hit, and no less than forty-six aircraft were destroyed in one of the most successful attacks against any British airfield throughout the war. After seventy-five hours of instruction on the Oxford, Patterson was posted to Kinloss to learn to fly the Whitley at 19 Operational Training Unit (OTU). After a few sorties it was clear that the 5ft 6in Patterson was having difficulties with the rudder pedals, and he was ‘taken off Whitleys due to shortage of stature’. This pleased him a great deal since he had always wanted to fly the Blenheim, and he was promptly sent to Upwood in Cambridgeshire and to 17 OTU to convert to the twin-engine bomber. He flew his first sortie with Flight Lieutenant Derek Rowe DFC, ‘a 21-year-old veteran’, and soon afterwards formed his own crew with Sergeant Shaddick as navigator and Sergeant Griffiths as air gunner. The latter would fly all his operational hours with Patterson. After some seventy hours’ flying, he completed the course, was commissioned as a Pilot Officer, and posted with his crew to 114 Squadron equipped with the Blenheim IV at Thornaby on Teesside.

Charles Patterson as a very youthful 21-year old Acting Squadron Leader. (Charles Patterson)

By the time Patterson finished his training at the OTU in April 1941, the fear of a German invasion had abated, but the threat from the U-boat menace in the Atlantic was increasing. The aircraft of Coastal Command needed to be relieved of the onerous task of patrolling the North Sea in order to concentrate their operations against the U-boats, and a number of 2 Group Blenheim Squadrons were detached to the Command to take on the patrols over the North Sea. These included 114 Squadron, and Patterson flew his first war sortie, a convoy escort, on 28 April 1941 from Thornaby in V 5888, an aircraft he would fly throughout his tour on the Squadron.

Orders were given to the AOC 2 Group, Air Vice-Marshal Stevenson, to halt the movement of all enemy shipping between Brittany and southern Norway ‘whatever the cost’. To avoid detection by radar, aircraft had to attack at very low level and make the maximum tactical use of cloud. The North Sea was divided into a series of ‘beats’, which had to be patrolled constantly by groups of aircraft flying in line abreast so that any ship sighted would come under a concentrated attack. The weather had an impact on tactics and determined the number of aircraft allocated to a ‘beat’. Patterson flew a number of these patrols off the Norwegian coast and, on one occasion, attacked a ship from fifty feet during a patrol from Leuchars.

All anti-shipping operations had proved extremely dangerous in the face of the increasingly powerful flak, and the Blenheims were gradually withdrawn and returned to 2 Group. Patterson had flown twenty-six patrols by the time his Squadron flew in formation to West Raynham on 19 July to recommence ‘Circus’ operations against targets in northern France. He also found himself appointed as a Flight Commander and promoted to the rank of Acting Flight Lieutenant, just three months after joining the Squadron.

The Squadron flew its first Circus within three days of returning from Scotland. The basic formation used was a close box of six Blenheims comprising two sections flying in vic, with the second slightly stepped down. Fighters provided close escort with others flying on the flanks, and a further Squadron giving top cover. Up to twenty-four Blenheims, armed with four 250-lb GP bombs, formed the bomber force operating at 12,000 to 14,000 feet, placing them above the light flak. Patterson led the second vic of three against the sheds and slipways at Le Trait, and the following day, the ammunition dumps near St Omer were bombed from 12,000 feet. Flying in the formation was Sergeant Ivor Broom on one of his first operations. Many years later he retired as an Air Marshal and a much decorated bomber pilot.

On 24 July the Blenheims of 2 Group were used to mount a major attack against Cherbourg in support of a large force of heavy bombers attacking the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at La Pallice and Brest. No. 114 Squadron provided twelve Blenheims and attacked after three other Squadrons had already bombed – Patterson was leading the second section in V 5888. The flak was intense, and four aircraft were damaged as they bombed from 12,000 feet. Air gunners reported hits and heavy black smoke in the vicinity of the target.

Early in August the 2 Group Blenheim Squadrons carried out a period of intensive low-level flying training in preparation for one of the most spectacular operations it ever mounted. The aircrew were not aware of the purpose for such activity but, as one of the Flight Commanders, Charles Patterson, was told confidentially of the target in the afternoon of 10 August, two days before the attack. He hardly slept that night. ‘Operation 77’ was mounted to fulfil a number of requirements of the current bombing campaign. It was a deep penetration, in daylight, into Germany with the aim of hitting a major target and drawing fighters from the Russian Front in the expectation that other similar attacks would follow. The targets chosen were the main power stations at Knapsack and Quadrath Fortuna near Cologne. Knapsack had the largest steam generators in Europe and was capable of producing 600,000 kilowatts. Quadrath could generate 200,000 kilowatts, and together they produced much of the electricity needed by the industries of the Ruhr.

A force of fifty-four Blenheims, drawn from six Squadrons, provided the main attacking force, with eighteen aircraft attacking Quadrath and thirty-six tasked to bomb Knapsack. Leading the Knapsack force was 114 Squadron with its new Commanding Officer, Wing Commander John Nichol, and each of the aircraft carried two 500-lb GP bombs with an eleven-second-delay fuse. Patterson was appointed deputy to the leader. A Circus operation of eighty-four fighters escorting six Hampdens also took off to attack targets in northern France, and to act as a diversionary force to attract the St Omer-based Messchersmitt Bf 109s away from the Blenheim force, a tactic that worked well. Four of the RAF’s new B-17 Flying Fortress bombers of 90 Squadron also flew diversionary raids at almost 30,000 feet with the aim of drawing off the fighters from the low-flying Blenheims.

Shortly after 0900 the Blenheims took off to head for Orfordness, and the rendezvous with the escorting force of Whirlwind fighters of 263 Squadron. The large force set course over the North Sea for Holland flying at low level in loose formation. As it penetrated through the mouth of the Scheldt estuary to Antwerp, the Whirlwinds had to return, and the Blenheims pressed on alone over the flat Dutch countryside to Cologne. The visibility was good and the prominent tall chimneys of the Knapsack power station could be seen clearly as the formation split to attack their targets. Nichol made a gentle turn to starboard to line up on the primary target, flying between the chimneys as he released his bombs with Patterson still formating on his wing. The flak batteries opened up, but the 114 Squadron aircraft emerged unscathed to join up for the return flight.

Everyone had anticipated that the return flight would be the most hazardous, but enemy fighters failed to appear as the Blenheims raced on to make their rendezvous with a Spitfire Wing. But, just as the Blenheims thought they were clear, the Messerschmitt Bf 109s of JG 1 and JG 26 found the returning bombers. The Spitfires entered the fray when numerous air battles took place, but some of the enemy fighters got through to the low-flying bombers. Nichol called his crews to tighten formation as he descended even lower, with his gunner, Pilot Officer J. Morton, calling evasive tactics as the formation flew down the Scheldt and out to sea where the enemy fighters finally broke off their attack.

With a great sense of relief, the Blenheim crews climbed to 500 feet as a further Wing of Spitfires arrived to escort the bombers home. The raid had been a great success and made headline news, but it had been achieved at a loss. Twelve of the fifty-four Blenheims failed to return and many others returned damaged. In recognition of his outstanding leadership, Wing Commander Nichol was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. Many, including his station commander, the Earl of Bandon, and Charles Patterson felt that he deserved the Victoria Cross. Tragically, he was lost a week later and never learnt of his award.

Two days later Circus operations were resumed when Patterson led six aircraft to Boulogne to attack the docks, and this was followed by more of the feared shipping beats during which he attacked a 300-ton trawler. With mounting losses among the Blenheim crews, the 21-year-old ‘veteran’ Charles Patterson was promoted to Acting Squadron Leader just five months after joining the Squadron as a Pilot Officer.

On 4 September Patterson led six aircraft, with a Spitfire and Whirlwind escort, against a whale oil ship at Cherbourg. The formation was met by intense flak during the bombing run at 8,000 feet, and the Whirlwinds broke off to drive away a formation of approaching Bf 109s. As the Blenheims departed, the Exeter Spitfire Wing arrived to escort them home.

By mid-September Patterson’s tour with 114 Squadron was drawing to a close. On 27 September he led twelve aircraft on Circus 103, an attack against the power station at Mazingarbe in France. Fighters of the Hornchurch Wing escorted the aircraft as they bombed with 500-lb bombs and 40-lb incendiaries from 15,000 feet. At 1600 he landed back at West Raynham and climbed out of V 5888 for the last time at the end of his fortieth operation. Shortly afterwards it was announced that he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The citation, endorsed by Group Captain the Earl of Bandon, drew attention to his role as a section leader on the Knapsack raid and concluded ‘He has shown great zeal and devotion to duty and his work has always been a fine example to his Flight.’ Patterson was particularly delighted when his long-standing air gunner, who had been with him on every operation, Sergeant Alan Griffiths, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal.

For the next ten months Patterson instructed on the Blenheim Conversion Flight of 17 OTU at Upwood before returning to operational flying. After a brief spell flying Bostons with 88 Squadron, he transferred to 105 Squadron – the first to be equipped with the Mosquito, and commanded by Wing Commander Hughie Edwards VC, DFC. The superior performance of the Mosquito soon became apparent. Whereas a training navigation exercise in a Blenheim was a triangular route round the centre of England, the route in a Mosquito was a triangle around the British Isles – and completed in a similar time.

After just three sorties on the Mosquito, Patterson and his navigator, Sergeant Egan, found themselves flying DK 338 on their first operation. Led by the legendary crew of Roy Ralston and Syd Clayton, they took off on 22 September 1942 for a low-level daylight attack against the coke ovens at Ijmuiden, dropping four 500-lb GP delay-fused bombs in the face of intense light flak. Four days later, Patterson flew his second operation, a daylight weather reconnaissance sortie requested by Air Marshal Harris who intended to mount a large raid with his heavy bombers that night. Flying at 25,000 feet over Germany, the route took him to Magdeburg, Rostock, Kiel and Esjberg – a sortie completed in just over four hours and covering 1,200-miles, the absolute maximum range for a Mosquito IV. On landing, the crew were met by Hughie Edwards who explained that he was both delighted and surprised to see them back. Throughout the afternoon, the RAF listening posts had intercepted numerous German broadcasts scrambling fighters to engage the high-flying Mosquito – the only RAF aircraft over Germany that day – and Patterson and his navigator had been given up as lost. Throughout the Flight they had not seen a single fighter!

By early October the second Mosquito Squadron, 139 Squadron, had become operational and revised battle orders were issued for the two Mosquito Squadrons. Their primary role was to attack industrial targets deep in Germany, not only to destroy factories but also to act as nuisance raids to affect the morale of the civilian population. After night-time raids by the heavy bomber force, Mosquitoes would return the following night. The aircraft’s secondary role was the attack against specific industries by small formations. Patterson flew a number of sorties deep into Germany, but by the middle of November the two Squadrons found themselves conducting a concentrated series of low-level exercises. Unknown to the crews, HQ 2 Group was planning the most ambitious low-level daylight operation of the war: Operation ‘Oyster’, the attack against the Philips radio and valve works at Eindhoven.

During the training period Wing Commander Edwards took Patterson on one side and told him that he had been ‘selected’ to fly a specialist reconnaissance task using a cine-camera mounted in the nose of his Mosquito. He was to fly down the Scheldt estuary to the German fighter airfield at Woensdrecht taking films that would be used to brief the crews taking part in the forthcoming attack. However, to create the correct perspective, he would have to fly at 400 feet, and this would give the German radars ample warning of his approach. In his unarmed Mosquito he would have to rely on surprise and the aircraft’s speed to avoid being intercepted. On 20 November he took off in DK 338 to fly the sortie. His arrival took the Germans by surprise and they failed to intercept him, and he was back at Marham with his film two hours later. It was the beginning of an exceptional chapter in the remarkable operational career of Charles Patterson.

The plan for the Eindhoven attack was complex. The Bostons, Venturas and Mosquitoes of 2 Group had very different performances, yet the aim was to condense the raid into the shortest possible time. As a result, the Bostons were selected to lead the attack followed by the Mosquitoes with the slow Venturas bringing up the rear. Ninety medium bombers were assigned to the task with Spitfire and Mustang Wings tasked to provide escorts. The raid was planned to take place early during the morning of 6 December – a Sunday was chosen to minimise casualties among the Dutch work force, who would be at home.

Wing Commander Hughie Edwards led the twelve Mosquitoes, with Patterson flying at the rear of the second section. The cine-camera had been fitted in the nose of his aircraft, and he was to film the attack as he dropped his 500-lb bombs. As the formation passed Woensdrecht, Bf 109s rose to intercept, and two Mosquitoes broke formation to draw the enemy fighters from the rest of the formation leaving Patterson to lead the second section. The heroic gamble worked, allowing the Mosquitoes to attack the northerly target unmolested. Three miles short of the target they pulled up to 1,500 feet to commence their shallow dive-bombing attack with their delay-fused bombs. Immediately after releasing his bombs and running his camera, Patterson broke to the north at treetop height to make his way home at low level. To avoid the enemy defences, he flew north to the Zuider Zee and into the North Sea near the island of Vliehors – a tactic he would use on many more occasions.

Although the losses were high, the raid was a great success, and the factory did not return to full production for almost six months. For his leadership of the Mosquito formation, Hughie Edwards added a Distinguished Service Order to his VC and DFC.

Shortly after the raid on Eindhoven, Patterson was told that he would be the RAF Film Unit’s pilot, and he was sent to Hatfield to select a Mosquito IV to use for all his future sorties. He selected DZ 414, which became ‘O for Orange’ and he would fly the rest of his many operations in this aircraft. On 13 February 1943 he took it to Lorient on its first operation following behind the main attack force. It was the beginning of a remarkable career for the aircraft, which flew 24,000 operational miles during the war. Patterson flew virtually all the sorties in the aircraft amassing 20,000 miles. It was always armed with four 500-lb bombs, and Patterson flew a few minutes behind the main formation – by which time all the enemy defences were alerted – dropping his bombs as the cine-camera recorded the results of the raid.