8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

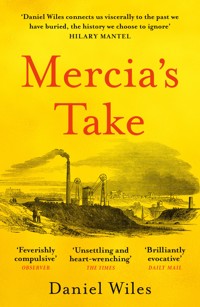

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'A brilliant debut' Guardian 1870s, the Black Country. Michael is a miner. But it's no life for a man. Michael exhausts himself working two jobs, to send his son Luke to school, so he won't have to be a miner too. Down the pit one day, he finds a seam of gold. If he gets it out, he can save his own life, and Luke's. But his workmate has other ideas… Mercia's Take summons an England in the heat of the industrial revolution, and the lives it took to make it. Gripping, powerful and intense, it is the debut of an astonishing new talent.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 178

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Contents

IIIIIIIVVVIVIIVIIIIXXXIXIIXIIIXIVXVXVIXVIIXVIIIXIXXXXXIXXIIXXIIIXXIVAcknowledgementsI

Michael stood in the cage. It was about ten feet wide and long. A dozen other men followed. Squeezed tight. Michael wore an ashen grey cotton shirt that had once been white. Outside the cage men and women moved around the vast sea of black land, down its hills and banks, in and out of its offices. He watched them. Women unhooked and hauled tubs of coal from the pithead and sent them down the bank. The giant pit wheel breathed slow and incessant. He stood as each other man, soldierlike with caged eyes. Waiting.

Winter soon.

He looked down at the man who spoke. A fellow hewer. Already halfnaked and bearing scars across his chest that scored his sootfogged skin. His stature unusually small. His hands unusually large. Michael recognised him.

Suppose weem paired up.

Ow’s that? the fellow hewer said.

Lawrence day tell ye?

Work me stall. Cor spake to that cunt.

Needn’t bite hands that feed ye.

Juss doe fancy spakin to him is all.

Westward groups of gulls laughed. Central to the bank the giant chimney sicked up stormblack smoke, creating a lingering baldachin. The steam engines rattled loud and hot, a constant alarm. Dead leaves from surrounding woodland carried across the ground by autumnal wind. Magpies and crows amongst the black earth. How many of the former were good fortune?

So, what was ye told? the fellow hewer said, looking up to him and smiling with his last few teeth different shades of brown.

That om to be paired up wi someone who looks as ye. Cain, is it?

Ar.

Michael.

So yowm new.

Ar.

Where frum?

Brownhills, Michael said, turning to Cain, who still stared at him with that partial smile plugged with chewing tobacco. His face viewed better now. Around the mouth a scratched patchy beard dyed with soot and slick with oil. His nose daftly small like a shirt pocket button and stabbing silver eyes that shone oddly bright.

The huge iron chain that held the cage started to move. Mechanical breaks like the cracking of fingerbones. The cage sunk and with it the miners. Everyone started to undress to their long johns and held their clothes clutched against their groins. Dark grey light swapped for the hot glow of Davy lamps and candles. The heat bathed them slowly from toe to head.

Chokedamp, sweat and manure invaded Michael’s nostrils. The shouts of the colliers and snap of the hewers picking at the walls. As the cage was swallowed into the belly of the earth he looked up and saw a child peering over the lip of the mine.

This earth takes its workers from an early age. Never got used to the sight. How could he. It was supposed to be outlawed now, supposed to be getting better. But it seemed each time he stepped onto this working land, it was one child more. One child more and eventually we can forget it was outlawed in the first place.

The cage hit the floor. Everyone stepped off. The workers replaced by the morning shift oozed lazily from the sump and onto the cage. The cheerful noise they brought with them that could only be described as end of shift excitement, left with them up the shaft. The wind gone now. Air stagnant and damp. Michael looked about him whilst the other men spoke to the underground manager.

Ours is five, Cain shouted.

They left their clothes in buckets on the sump floor and picked up Davy lamps and walked down the inbye. Immediately they were met by a young boy with iron chains around his waist. He was pulling a small skip of coal along the narrow track road. The boy was covered in erosions where the chains rubbed against his skin. He looked up at the men. They moved. He carried on.

Michael looked down at him again and noticed twinkling blisters all about his body that were bleeding from the centre. The boy winced with each step. The only part of his face left free of black were the lines around his eyes. He fell to his knees and slowly took off his chains. Their links clanged against each other before dropping to the floor with a dull thud. He approached the undermanager, who presently took a stick that he kept under his wing and started whipping him.

Leave the nipper, Michael said.

The undermanager looked at him from up the inbye, inclined so he had three feet on him. Cain nudged Michael and said, Less goo.

Through the crowd of miners, the undermanager’s dark shape was fixed on him.

The central pit was a fair size, and on the far side there were channels that led to different stalls. The ground was logged with deep black water that held glowing shapes reflected from the lamplight. Moving and dancing. Wooden beams supporting the ceiling disappeared into the water. Men waded through it ignorant of its murk and scum that varnished the surface. Cain and Michael did also.

They walked past the unsteady fire of a furnace that moved foul gases and smells of the mine haphazardly through an upcast.

Two boys emerged from a small air hole. They looked unhuman, like some blind, bald rodents unearthing themselves in search of scraps of candlelight.

This he had saw before, it was he fifteen years ago. Picked up by a man after midnight and worked until sundown. He saw the darkness. He saw the nothing. In the winter, he would go months without feeling the sun on his face. But kids always preferred this job to haulage work. It was frightening and dangerous, but without the pain of iron chains pulling on the skin, the odd shapes that spectred yellow on the wall. The angry men. The ache. The tire. The fear of the undermanager’s whip.

He reached into his trouser pocket and lit a candle with his lamp and handed it to the boy. When the child took it he realised it was a girl. She handled it like a timid squirrel taking a nut. The two children, stark naked, held the candle carefully between them. It was as if they were praying to it. It lit up their faces blotted with soot. Already it dripped onto their hands and ran down their wrists. They burrowed back into the vein of the mine. He moved into the arteries.

From there the mine took three different directions. Each artery had only enough room for men to crouchwalk. Michael was a tall man and struggled to fit in them at all. The sweating body scratched by the rough walls. Cain moved down the tunnel with ease. Inside these walls clews of grey worms earthlodged.

At each stall the mine opened up a bit where the miners were already at work with pickaxes. The clap of sharp shots. He shouted at them when they swung back and almost hit him. One man on stall three turned and stared at him. He was bald, looked around fifty and had burn scars covering most of his face. Monstrous and devoid of all facial expressions.

When he reached the fifth stall Cain was already busy on it. It was hardly opened up at all. Indented about four feet tunnelside. He placed his Davy lamp on the floor and knelt and took off his boot and shook the water from it and after doing the same with the other he lifted the pickaxe and struck it against the coal. Then the two of them spoke in between pops of pickaxe.

Why do that? Cain said.

What.

The lad.

Any a nipper.

Doe trouble yaself wi it.

Ye got young a yown?

No response. Michael stole a look to his side as they hit the surface at a steady pace.

Boy has a choice to work the mine, Cain said.

Doe know that.

Is yown workin down ere?

Ay of age yet. Doe want him down ere though. Thass why om workin two mines now, so he can goo to school.

Ow old bin he?

Six.

So yowm still workin up Brownhills?

Ar.

Hewin?

On aulage mostly.

Cain stopped. The blood orange marble from the Davy lamp lit up his wide black eyes. Well I doe know if yowm more sense than stupid, he said.

A few hours into the shift. Empty tubs were pushed along the tunnel track to each stall. The miners loaded only decent sized pieces of coal into them. The breakaway pieces, or slack, were small, thin and slatelike. They were raked and saved for their own tub at end of shift.

When their tub was loaded with good coal it was pulled down the track by one of the boys. Michael watched the chains tighten around the lad and shook his head. Cain day stop hewing the wall.

Everything moved in the mine like finetuned machinery. The song of the hewers met with the melodies of the haulers and hellish bellowing of the undermanager. Every now and then they stopped for breaks, and if they could afford it, had their snap.

The snap was usually in the form of a sandwich. They used timber to sit on and the coalface to rest against. It was the same wall that they earned their money from, that they pissed against, that they cursed for shooting off bits of soot and dust that clawed at their throats and sent them into mean fits of coughing.

The coughing was a symptom of the job. Once the black gets in, it woe leave. It can only get worse. Only thing you can do is keep it at arm’s length.

Michael spoke not a word more to Cain. They sat quietly for five minutes, chewing their bits of bread. Sniffing. Coughing. Scratching their heads.

His shift ended. He and the other men and women were loaded back onto the cage and spewed from the mine. First stop was the checkweighman’s office.

The wooden beams held up a small shack that wor built for comfort. The checkweighman was sat at a desk under a lamp with his books. He was weighing the last few tubs as the last of the feeble day lingered in the room.

The men lined up for their payslips. When the miners at stall five got theirs, Cain snarled at the checkweighman.

The fuck is this?

Under the glow of the lamplight the checkweighman was hunched over his desk. He turned his eye to Cain and at the same time pulled his shoulder up and hunched over even more. Not this again, he said.

We sent five full tubs out today.

I juss weigh em an write it down. Forget yow elected me for this job?

Cain laughed. I day elect ye for nothin.

Next, the checkweighman said.

Michael folded the slip into his pocket and walked around the shack and watched the light fall away from the sky.

Michael in the payroll office. As each one left the room another was asked, Scrip or bob? And when he reached the front he was asked the same.

He already was paid in scrip tokens for the tommy shop at his first work. Easier that way. The mine always stocked the tommy well, and it was right next door. The tommy shop here was the same. But he asked for a few bob instead. He had it worked out. His first work was for scrip, and this one for bob. He wanted to visit Pelsall village with it and a sense of achievement in his pocket.

The man took his payslip. Bob’s less value than tokens, ye know that? he said, looking up at Michael over his spectacles.

Michael frowned. Why?

Juss the way it is. If ye want cash then we take away a percentage.

He arrived just before closing. A family should never look upon a loaf a bread as luxury, the baker said, shuffling about behind the counter. Keep this un, pay me next time.

Can pay for it, Michael said, handing across the coin.

The village empty save a few partied crows and pigeons in dead trees that lined the streets and rowdy dregs that hung outside the pub. A shout of accusation. Jeering of a crowd. Towards the south a red glowing skyline. The sun long set. This crude painting the living beast of industry, the chosen child to the earth’s breast with its perfect heart beating metronomically throughout the night. He held the loaf under his arm and walked.

Along the cut desolation of light save the distant glow of the fires and furnaces. He trudged through mucked puddles, each of his boots sticking for a second before being sucked back out. Nesting coots squeaked from the reeds on the opposite bank. Nocturnal mallards huddled with beaded eyes watching him pass. Clouds of gnats about his head. Swifts swung about screaming from hedgerow to hedgerow.

Fork lightning over the horizon. Whitish purple against the red. A figure came. He day notice it until it was five feet ahead. It was a lad. He was bleeding down his neck and his cream shirt was ripped loose at the arm. Deep gurgling thunder. The lad went past him, head down but looking up at Michael from the corners of his eyes. Turbulent quacks of ducks. He turned around. The lad was sprinting barefoot down the cut.

He walked to the new iron bridge. Used it to cross the cut and followed a path until he arrived at a small bungalow. From outside a small haven from the smoke and rain. Warm yellow windowlight. He wiped his boots on the brown bristled mat, opened the door, and walked in.

II

He leaned on the doorframe to slip off his boots. The smell of hot gravied soup. A voice shouted from the kitchen.

What? he said.

Juss in time, she said, drying her hands with a darkened tea towel. He handed the bread to his wife of five years, Jane. Her hands were small but aged, with large knuckles and rough skin. She wore an offwhite apron over a long grey dress. It reached the floor and masked her figure. She had mousey blonde hair tied back tightly save for a few thin strands that fell down the sides of her rosy cheeks. Her eyes were small and black. Thank yow, she said, washin before tea?

Ar, he said.

He removed his clothes and followed her to the back door. She swung it open and handed him a metal bucket. The rain had started to beat down harder. He took the bucket along the small brick path that led to the well. He yanked the pump a handful of times and waited. The smack of the water from the tap almost drowned out by the rain.

Inside the outhouse, he knelt and plunged his black hands into the water and lifted it up over his head and face and down the back of his neck. When he heard a tapping noise, he rubbed his eyes clear and turned to it. Luke was standing there holding a light.

Alright son, he said, and continued to scrub himself.

Ready for tea?

In a minute.

He sat himself down next to Jane as she spooned the stew into bowls. His face clean.

The boy started on his stew too quickly. He spat it back out and held his hand to his mouth.

Now look what yowve done. Remember to blow on it, Jane said.

Michael grabbed some bread and forced it in and around the bowl and soggied it. He looked at Jane, slowly blowing on her spoonful before tentatively eating. She was smiling. He rarely saw her without one. She caught him staring. He shifted his eyes towards Luke.

School soon, he said, to which the boy nodded and carried on blowing on his spoon. Doe let em bully ye. Yowm startin late but iss better than never. Enjoy it.

The coal fire burned with a rumble and spat every now and then. He cor tell whether the boy was excited or not. It was possible he felt neither excitement nor worry.

After the boy was put to bed, Michael sat with Jane as she sewed the holes in his socks. She was perched on the chair next to the fire. He lay on his back supported by his elbow and warmed his eyes by the fire.

Ow was the new place then? she said.

Alright. Met a strange bloke. Name was Cain.

Oh ar?

Ar. I reckon him a fruitcake.

Why?

Juss the way he carried himself. Queer way about him.

Always so quick to judge people, Michael.

He thought me mad for tekkin up two jobs.

I think yow mad for it an all.

Om alright, he said, closing the hot lids of his eyes to rest the lenses from the heat.

She stopped sewing. I wish I could help, she said. I feel like a bother.

He shook his head and looked down at his fingers. Cleared the dirt from his nails on his left hand with the corner of his righthand thumbnail. Nay. Nay. Yowm not.

The fire sank into every part of him, wrapping around him like a coat. If only it had been him and not her that them skips fell on. If only. Laid up in bed for months and changed forever. If she were in his boots, she would understand why he day find her a bother, why they could nay help their lot and he day blame her for it. Still, they never spoke of the accident in depth. What repercussions it caused. How it changed her. It happened before they met after all, and he day want to prod too much. Over the years he had thought about mentioning it in passing, in a lighthearted way, as though they were talking about the weather. What did it feel like when they came down on ye? When did ye find out ye was barren? What did that feel like then? But the words would never form. How do ye ask someone of such things?

III

It was almost ten at night when he left home. He had to walk along the cut for a mile before he reached the Brownhills colliery. Again he walked the sludgy canalside where bats fluttered about the old trees.

Ossdrawn barges churned up silt from the cut floor as they slithered past. Barges hauling coal, barges hauling limestone, barges that held families and pilgrims. One boat held so many people that some nippers even swam behind it in the dark water, only visible by the light that hung behind the boat. Dogs swam with them, their eyes reflecting like buoyed beacons.

As he got closer to the colliery he saw the lights and heard the noise. Engines and waggons and people. Heat drew upon him like a daemonic wind. Geese westward against the pale waning moon.

He crossed the far side of the bank. Past the pit wheels and the bankswomen. Past two young girls clinging to their mother’s feet, sobbing painful words.

There wor a cage that he entered in this mine. Instead he stepped down a narrow turnpike staircase. He walked along the wide, hewed hallways filled with osses dragging carts as men whipped them. Lights filled the walls.

He navigated the mine easily, travelling from tunnel to crosscut to tunnel to crosscut until he reached the main pit and reported to the undermanager.

Michael, ow bist?

Fit as a fiddle, and ye?

Back’s bin killin me.

Yowm walkin ay ya?

Ar?

So yowm fit. Ought to see some a these nippers.

The undermanager drew back, inverted his chin and looked at him sourly. Anyroad, he said, we ay got work on haulin for ye tonight. This is comin from above. Few a the osses keeled over, so.

Well I can work without em. Tay a problem.

We ay got enough men to push ya waggon. Them waggons am too big. Ye cor do it alone.

I car believe theym up for losin ow much money on a wasted waggon tonight?

I told ye, iss from above. Them Morris girls ay well so ye can work trappin.

Trappin?

Ar, he said, taking a pencil from behind his ear and turning his attention to his clipboard. Ye can trap or come back in the morra. Your choice.

The darkness swallowed everything. He had been sat there for hours opening and closing the trapdoor, forcing the foul gases out the mine.

He had taken the job of a child. The job of his childhood. All about the mine the sounds were various, but in this small corridor it was silent. The only noise was that of the sighing and whistling air that sought to escape around the door.