Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

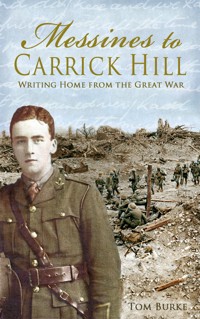

The book is structured around a collection of letters written by a nineteen year old Irish officer in the 6th Royal Irish Regiment, 2nd Lieutenant Michael Wall from Carrick Hill, near Malahide in north Co. Dublin. Michael was educated by the Christian Brothers in Dublin and destined to study science at UCD before being seduced by the illusion of adventure through war. By contextualising and expanding the content of Wall's letters and setting them within the entrenched battle zone of the Messines Ridge, Burke offers a unique insight into the trench life this young Irish man experienced, his disillusionment with war and his desire to get home. Burke also presents an account of the origin, preparations and successful execution of the battle to take Wijtschate on 7 June 1917 in which the 16th (Irish) and 36th (Ulster) Divisions played a pivotal role. In conclusion Burke offers an insight into the contentious subject of remembrance of the First World War in Ireland in the late 1920s

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 448

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Thomas Burke, 2017

ISBN: 978 1 78117 484 5

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 485 2

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 486 9

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

All characters and events in this book are entirely fictional. Any resemblance to any person, living or dead, which may occur inadvertently, is completely unintentional.

Contents

Abbreviations & Acronyms

Preface

1 Innocence

2 Smitten by War

3 ‘Fancy the Royal Irish captured Moore Street’

4 Dear Mother,You Are Not to Worry

5 The Road to Wijtschate

6 Michael’s New Home in Flanders

7 Back to School

8 ‘Shamrock grows nowhere else but Ireland’

9 ‘I stick to my rosary’

10 Life in the Reserve around Loker, Kemmel and Dranouter

11 ‘Curious times’

12 Paddy’s Day at Loker

13 The Swallows Have Arrived

14 Training and Away from the Guns for a While

15 ‘We’ll hold Derry’s Walls’ – Relations between the Irish Divisions in Flanders

16 ‘God grant that I come through … we have let Hell loose’

17 ‘Come on the Royal Irish’

18 One Haversack and Six Religious Medallions

19 Remembrance

20 Michael’s Belated Funeral – a Personal Reflection

Endnotes

Bibliography

About the Author

About the Publisher

Abbreviations & Acronyms

BEF British Expeditionary Force

CBS Christian Brothers School

CF Chaplain to the Forces

CWGC Commonwealth War Graves Commission

DCM Distinguished Conduct Medal

DSO Distinguished Service Order

GHQ General Headquarters

GOC General Officer Commanding

GPO General Post Office

HMT His/Her Majesty’s Transport

IWM Imperial War Museum

LHCMA Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives

NAK National Archives, Kew

NCO Non-commissioned Officer

OR Other Rank

OTC Officers’ Training Corps

RAMC Royal Army Medical Corps

RASC Royal Army Service Corps

RDF Royal Dublin Fusiliers

RDFA Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association

RFA Royal Field Artillery

RFC Royal Flying Corps

RHMS Royal Hibernian Military School

SJ Society of Jesus

SP Strong Point

UCD University College Dublin

UVF Ulster Volunteer Force

VC Victoria Cross

VD Venereal Disease

Preface

On 28 January 1999 Mrs Rosemary Kavanagh of Warner’s Lane, Dublin, wrote me a letter addressed to the Dublin Civic Museum in South William Street.1 She informed me in the letter that she had recently come into possession of a bundle of documents containing letters, telegrams and some photographs that had once belonged to Michael Wall, a young relative of her husband. She explained that Michael was an Irish officer who served in the Royal Irish Regiment during the First World War. The majority of the letters by Michael were written from the trenches in Flanders to his mother in Carrick Hill near Malahide in north County Dublin. The documents had come into Rosemary’s possession following the death of Michael’s younger brother Bernard, or Barney as he was known to family and friends. Barney never married and safely kept Michael’s papers for many years in his home in Blackrock, County Dublin. He died in August 1998 at the age of ninety. Rosemary graciously offered the documents as a donation to the archive of The Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association (RDFA).

It wasn’t until the middle of March 1999 that I got round to visiting Rosemary, her husband, Andy, and their daughter, Jane. I spent an entire afternoon and evening reading these simple but heart-rending letters. So emotionally moved was I by these letters that I made a promise to myself, to Rosemary and her family, and most of all to Michael that someday I would use his letters to write an account of his time in Flanders.

No matter how Michael’s story was going to be told, it had to be set within the larger story of the First World War and in particular the Battle of Wijtschate and Messines, which took place in early June 1917.2 After I received Michael’s letters, I spent several years researching the Irish participation in this battle in great detail. The end product of the research was an unpublished 500-page treatise that essentially told the story of how the 16th (Irish) and 36th (Ulster) Divisions took the village of Wijtschate from the Germans on 7 June 1917.3 Having completed the work, I realised that Michael’s story was lost in this vast script, in which the emphasis was on the battle itself and not on Michael Wall.4 Consequently, I decided the best way to tell this young man’s story was to let him tell it himself, by reducing emphasis on the battle and paying greater attention to the content of his letters. To add a sense of place and reality, the letters – all of which are dated – are set against his battalion’s locations and activities in Flanders.5Moreover, to explain the background of the sentiments Michael expressed and the topics to which he referred, the narrative is expanded and contextualised.

I would like to thank some of the people who helped me produce Michael’s story. There are few regrets I have in life, but, sad to say, one I do have is the fact that Rosemary never got to see the fruits of my work. She died peacefully at St Vincent’s University Hospital in Dublin on 23 June 2016. So to Rosemary, Andy, Jane and all the Kavanagh family, I simply say thank you for giving me his letters and the privilege of writing his story. To my dear friends and comrades in the RDFA – Sean Connolly, Brian Moroney, Captain (retired) Seamus Greene, Philip Lecane, Nick Broughall and the late Pat Hogarty – thank you for your friendship, kindness and generosity.

I have always believed that if one is going to write about a battle, one must walk the battlefield – or in my case cycle it. For many years I have cycled round the laneways and roads that once passed through the battlefield on the eastern and western sides of Wijtschate and Messines to see where a camp called the Curragh Camp and hutment lines called Tralee Lines and Shankill Lines once stood full of Irish men. I simply could not have survived in the Heuvelland region of Flanders without the help of Mrs Trees Vanneste, her husband, Marc, and also Mr Johan Vandelanotte, who, sadly, passed away too young on 26 October 2016. I thank them for their kindness and hospitality on my many trips to the region.

I thank, too, my dear friends Erwin and Mia Ureel. Erwin is a Flemish man who for many years, unknown to most people in Ireland, has worked tirelessly to keep alive the memory of the Irish soldiers who fought and died in his country. To mark the 100th anniversary of the Christmas Truce of December 1914, Erwin, Sean Connolly and I camped out on the old front line near Prowse Point Cemetery on Christmas Eve 2014. It was a magical experience.

There were many people who read parts of my script and offered their opinions, which I valued. For their contribution I would like to thank Sean Connolly, Philip Lecane, Dr Tim Bowman of the University of Kent and Dr David Murphy of the National University of Ireland, Maynooth. There are also many people to whom I am very grateful for their advice on the location and sourcing of primary source material: Ellen Murphy and Dr Mary Clarke of the Dublin City Library and Archive; Billy Ervine of The Somme Heritage Centre in Newtownards; Fr Fergus O’Donoghue SJ of the Jesuit Archive in Leeson Street, Dublin; Cliff Walter of the Royal Signals Museum in Dorset; Alan Wakefield of The Photographic Archive in the Imperial War Museum, London; Aoife Lyons, librarian, National Gallery of Ireland; and Brother Tom Connolly, Edmund Rice House, Dublin. Thanks, too, to Martin Steffen for his help on German regiments. Thanks also to Mr George (RIP) and Mrs Mabel Pearson, Hillsborough, County Down, for allowing me access to the papers of Sergeant Andrew Lockhart; the editorial staff of Mercier Press, Wendy Logue, Noel O’Regan and Trish Myers Smith; my brother-in-law Trevor Wayman for his artistic skills; and my friend at Ulster Television, Paul Clark, who was so encouraging to me along the way.

To my mother, Annie, and my father, Ned, long since passed away, thank you for giving me the gift of an education. To my wife, Michele, and children, Carl, Jamie and Rachel, thank you for your support and encouragement during difficult times.

And so, after many a twist and turn to complete it, here is the story of one of Ireland’s lost generation of unfulfilled potential. This is my anthem for their doomed youth.

Tom Burke

June 2017

1 Innocence

Michael Thomas Wall, or ‘Al’ as he was known to family and friends, was born on 21 March 1898 in the fishing village of Howth, north County Dublin.1 His father, also named Michael, had been born on a farm near the village of Coolrain, County Laois; he worked as a bookkeeper in Howth.2 Michael’s mother, Theresa Carr, was born on 24 February 1872 and came from Dunbo Cottages, near Dunbo Terrace, behind the police station in Howth.3 Theresa and Michael Wall senior (who was a widower) met in Howth and were married in the old Catholic church in the village on 21 May 1897.4 Within a year of their marriage, Michael junior was born at Glentora, an elegant house situated on the fashionable Balkill Road in Howth. Over the next ten years, Michael senior and Theresa brought three more children into the world: Patrick Joseph, or ‘Joe’, in 1899; Agatha Mary in 1901; and Bernard, or ‘Barney’, on 20 August 1908.

In May 1906, at a little over eight years of age, young Michael enrolled in St Joseph’s Christian Brothers School (CBS) in the north Dublin suburb of Fairview.5 Each morning he travelled to school by tram from Howth along the coast road. The full fourteen-and-a-half kilometre journey to Nelson’s Pillar in central Dublin took about forty-five minutes; the fare was five pennies.6Within a month of his being at St Joseph’s, Michael had made an impression on his teacher, Brother M. S. O’Farrell, who wrote to Mrs Wall telling her that ‘Michael is a fine, talented child. He’s bound, if God spares him, to become a fine man.’7

The year 1908 was a good one for Michael. In August his mother gave birth to a baby boy she named Barney, and Michael passed his Standard III exam and advanced to Standard IV. Written on Michael’s Standard III certificate was a quotation by the writer John Ruskin (1819–1900), which the brothers used as a kind of motto: ‘Education is the leading of human souls to what is best.’ Brother Reid signed Michael’s certificate.

The following year St Joseph’s – or ‘Joey’s’ as it became known to generations of Dubliners – reached its twenty-first year and metaphorically had come of age (the school had been in operation since 1888). It had three Christian Brothers and three lay teachers teaching under the supervision of Brother Patrick Berchmans Reid (1880–1956), Master of Method in the Christian Brothers’ training school. The school hours were 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. In that year, Joey’s had a state inspection. The inspectors were pleased with the layout of the school, its cleanliness and the provision of blackboards and maps. They noted the presence of a library containing some 600 volumes, mostly books of adventure. They also noted that discipline was very good and that punishment was by means of a strap on the palm of the hand.8

Sometime after Barney was born, the Wall family had moved from Howth to 7 Hollybrook Road, Clontarf, a well-established parish about five kilometres north-east of Dublin city and near Fairview.9 A terrible tragedy struck this young family in December 1910 when Michael’s father died, aged forty-five, from cancer of the colon. He was buried in St Fintan’s Cemetery, Sutton, County Dublin. Michael was just twelve. The death of her husband left Theresa with a very young family and no regular source of income; the future looked bleak indeed.

Theresa’s sister Margaret, or ‘Margo’ for short, was one year older than her and had married a wealthy landowner, Sir Percy Willan. Their family residence was at Carrick Hill House, a grand country house with thirty-two rooms, near Portmarnock, also in north County Dublin. In an act of kindness, Margo offered Theresa and her young family part of her home in which to stay.Margo had suffered her own share of tragedy. She had married in 1899 and in 1903 gave birth to a boy named Cyril. Four years later, however, her husband ran off with Cyril’s nanny. He also left Margo near-penniless at the time by selling most of the farm’s livestock.10Before he had died, Theresa’s husband, Michael, with his farming experience, had helped to restock the farm at Carrick Hill. The exact date on which Michael junior and the rest of his family moved to Carrick Hill is not known, but it may well have been soon after he left Joey’s in January 1911.

The estate around Carrick Hill House consisted of about 263 acres of excellent farming land. It was a very active farm, with the main business coming from cattle, sheep and the growing of Russet eating apples for export.11The house itself was surrounded by beautiful gardens. It was customary with such large country houses to have live-in maids. Two lived at Carrick Hill: Bridget Marshall, aged thirty-one, who was single and from County Westmeath, and Elizabeth Clynn, seventeen and also single, from County Longford.12

Portmarnock was the nearest village to Michael’s new home.13In the early twentieth century, it was a typical small Irish country village with an economy that was based mainly on agriculture. Like many such villages at the time, Portmarnock had its share of local landlords and gentry. The bulk of the land around the village was in the hands of four families, namely the Jamesons (Protestant and associated with the distilling of Irish whiskey), the Plunketts (Roman Catholic), the Trumbulls (Protestant) and the Willans (Protestant). Probably the earliest landowners in the area were the Plunkett family, who were in Portmarnock as far back as 1733. They were also related to St Oliver Plunkett, who had been primate of Ireland in the seventeenth century. The Plunketts ran a brick factory in the village for nearly 200 years and, along with farming, provided the main source of employment in the parish. Out of the twenty-three families who lived in Portmarnock, sixteen lived on lands owned by the Plunkett family.14

Front (top) and rear views of Carrick Hill House, Carrick Hill, Portmarnock, County Dublin. Courtesy of the Kavanagh family.

Living and working on the Willan estate were six families.15Tommy Cunningham, the Land Steward who worked on the estate, lived there all his life. When Sir Percy departed, Margo had known nothing about farming and had relied on Tommy, who, through hard work, brought the farm back from near-bankruptcy. Cunningham was a decent, honest man, respected by those who worked under him. He died, aged eighty-eight, in 1956 and is buried in the Old Cemetery in Portmarnock.16 Harry Kealy, the local coalman’s brother, was the Willans’ shepherd.17 John Donnelly was the blacksmith; his forge and thatched family home were on the road leading up to the big house.

Mrs Connie Fowler, née Donnelly, was one of the blacksmith’s daughters. She could recall her father working in his forge when she was a little girl: the only light was ‘daylight which came in through the double door at the front … Among Dad’s regular customers was Cyril Willan, James Kealy, the local coalman, the Jamesons and the locals who had ponies for Sunday mass.’ She had fond memories of life in Portmarnock during the years of the First World War, especially on market day, which began with the collection of cabbages from the Willan estate. In the summer months, when the beach and golf course at Portmarnock attracted visitors, Connie’s mother opened a tea garden in the front garden of the house, with tables set with white linen tablecloths and decorated with flowers from the garden.18

Martha Reilly was born in Portmarnock in 1894. Her recollections of lazy, peaceful summer evenings present a further image of life around the Willan estate in the early twentieth century:

The Jamesons used to rent the Martello field from Willan for grassing and the cows used to walk from that field across the road and down onto the strand near the rocks at the Martello Tower. They used to paddle in the water and lie on the beach. It was lovely to watch them. At evening they would then move down the strand and across the sandy banks on their way to Jameson’s stables for milking.19

The Dublin artist Walter Osborne (1859–1903) was a regular summer visitor to Portmarnock. His paintings Cattle in the Sea, Milking Time in St Marnock’s Byre and On the Beach depict the scene Martha talked about.20

There was no Catholic church in the village of Portmarnock for centuries until the first one was dedicated on Sunday 22 July 1934. Consequently, folks had to travel, mainly by horse and cart, on the coast road from Portmarnock and Carrick Hill to the Church of St Peter and Paul in Baldoyle. The parish priest who looked after the spiritual needs of the Roman Catholics of Portmarnock, Carrick Hill and Baldoyle was Fr Robert Carrick (1833–1932). The children of the village went to the Jameson School, so named after the family who were the school’s early patrons from 1868. When the Jamesons visited the school, the children all had to stand up and sing ‘God Save the King’. The school was a national school for the village children between four and twelve years of age, and was in use until 1965.21

Apart from Michael, all of Theresa’s children were sent to Mount Sackville boarding school at Chapelizod in Dublin. Their fees were paid for by Margo. The common practice for boys who had completed their junior education at St Joseph’s was to transfer to the senior CBS – O’Connell Boys’ School in North Richmond Street, Dublin, named after Daniel O’Connell – and Michael, like many before him, followed this path. The compliments his teacher at St Joseph’s wrote about him being a ‘fine, talented child’ were quite genuine.22 Michael brought these talents with him into his early adolescence. In 1915 the Scholarship Committee of Dublin County Council offered Michael, who was by then seventeen, a county scholarship to study at University College Dublin (UCD).23During the summer of 1915 he completed his matriculation exams for entry into the National University of Ireland. His late application, however, denied him a place in college that year. Judging by the science subjects he studied over his four years at O’Connell CBS, such as elementary physics and magnetism, he no doubt would have pursued a degree in engineering or science.24

Life for Theresa’s young family seemed idyllic. Fresh air and all the pursuits of country living helped to ease the loss of a husband and father. Michael soon took on the mantle of being the man of the family. He settled into his new home and assumed the role of a young country squire. His destiny seemed to lie in a university education and a career in science or engineering. It is incredible to think that effects of the shock wave created by the assassination of an Austrian aristocrat and his wife by a Serbian nationalist on the streets of Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 trickled their way to a little coastal village in north County Dublin, and brought with them disaster and misery for some of its inhabitants.

2 Smitten by War

Michael Wall was only sixteen when the First World War broke out. At such a young and impressionable age, war and boyhood adventure went hand in hand. In early March 1915 he wrote to an acquaintance of the family, Francis Gleeson, who by then was a padre with the Royal Munster Fusiliers serving in France.1On 14 March Fr Gleeson replied to Michael’s letter; he thanked Michael for the shamrock he had sent. He found life at the front, ‘desolate and cheerless … a very hard one, but the loneliness is the worst’.2

Like so many young men of his generation, Michael may have been seduced by a vision of war presented to him in what he read in his youth. In the years leading up to the First World War, young boys who could read and afford them bought magazines such as The Boy’s Own, Pluck and The Boy’s Friend, which mythologised war with romantic and chivalric stories. Not only were these fictions a source of exciting escapist adventure, but they also promoted ‘patriotism, manliness and a simplistic imperial world view that emphasised duty and the need for sacrifice if the British Empire was to endure’.3According to Michael Paris, ‘adventure fictions, generally written for boys and young men aged between 10 and 18 years, were intended to inculcate patriotism, manliness, and a sense of duty to Crown and Empire among readers’.4 The library in St Joseph’s CBS in Fairview may not have had many books relating to the glory of the British Empire, but boyhood adventure was a central theme of many of the books.

Young German boys had their choice of pre-war patriotic, martial juvenile literature to read too. According to Sonja Muller:

Historic juvenile literature was the main genre and related to battles and wars of the past. Also popular were books on contemporary history. Titles like Um Freiheit und Vaterland (For Freedom and Fatherland), Die Helden des Burenkrieges (Heroes of the Boer War) or Der Weltkrieg, Deutsche Träume (World War, German Dreams) offered various ranges of militaristic literature.5

To add to the martial influences acting on Michael’s juvenile mind, the boys from the Royal Hibernian Military School (RHMS) in Phoenix Park, Dublin, spent their summer camp in the fields round Carrick Hill, where they practised drill and lived the outdoor life under canvas. The RHMS boys were at Carrick Hill in August 1915.6 With recruitment posters on display throughout the land, the war had come to Ireland, and recruitment was in full swing by late 1914. By the beginning of February 1915 approximately 50,107 Irishmen had enlisted in the army.7

Michael was too young to enlist legally. Recruits for the army at that time had to be between eighteen and thirty-eight years of age. However, despite his age, this war was not going to pass him by. Having an interest in science and engineering, on the advice of his friend R. W. Smyth at the RHMS, Michael applied for work in the engineering department at the Ministry of Munitions, which had an office at 32 Nassau Street in Dublin. On 25 September 1915 Staff Captain R. B. Kelly, who represented the Ministry of Munitions in Ireland, wrote to Michael declining his application but suggested that he should ‘communicate with Messrs Watt Ltd of Bridgefoot Street in Dublin’.8Michael didn’t seem to have much luck in obtaining work with Watt Ltd either, so, keen as ever, he reapplied to the Ministry of Munitions for work.

On 16 November he received another letter, from a Captain Browne, superintendent engineer for Dublin and South of Ireland, who informed Michael, ‘I have forwarded your application to W. H. Morton Esq. Loco Engineer, Midland Great Western Railway, Broadstone, Dublin, who will no doubt write to you in the course of a few posts.’9 But Michael’s ambitions to work in munitions never materialised. A week later, Smyth wrote to Michael suggesting he should try to enlist in the army.10 Two days later, on 25 November 1915, Michael filled out Army Form W.3075, which was to be completed by a ‘Candidate for a Commission in the Regular Army, Special Reserve or Territorial’.

The language used in Smyth’s letter to Michael is interesting to note. By using the words ‘they will all think the more of you for doing so’, Smyth tapped into the Edwardian sense of honour and manly pride, suggesting to Michael that ‘they’ – that is, those who knew him and perhaps his mother – would be proud of him for enlisting. In truth, his mother may have been proud of her son, but as Smyth also suggested, Michael’s enlistment did nothing for her peace of mind. No doubt some difficult words were exchanged between Michael and his mother when he told her that he had applied to join the army.

Michael had applied for a cadetship as an officer and not as an ordinary private soldier. His young country squire self-image and his coming from the ‘big house’ at Carrick Hill, with all the social standing and imagery associated with the big-house class, conditioned his ambition to take part in this war as an officer. It was adventure that drove Michael to enlist. He certainly did not do so out of economic necessity; after all, he came from comfortable surroundings and had a good academic career ahead of him in UCD. He was going to wear the uniform of an officer, a leader, an imagined heroic character from an adventure book and a representative of his assumed class.

Michael’s ambition to join the officer ranks was in contrast to a neighbour of his who also enlisted. Patrick (Pat) Redmond was the son of Plunkett’s chauffeur, James Redmond. Pat was twenty years of age when the war broke out, and he enlisted as a private in the 9th Royal Dublin Fusiliers (RDF).11 He was a general labourer and lived with his father, two sisters and two brothers in their three-room tenant-cottage on the Plunkett estate. His mother was dead.12 Pat’s and Michael’s different levels of entry into the army were dictated by their social class and were a reflection of the society from which they came. Their motivation for enlisting may also have been different. While Michael’s was adventure, Patrick’s may well have been economic.

Michael was not the only ex-Joey’s CBS boy who enlisted in the British Army. Tom O’Mara from the Howth Road in Clontarf was commissioned a lieutenant. Thomas Saurin from 3 Seafield Road, also in Clontarf, who had passed the Middle Grade exam at St Joseph’s in 1910, served with the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) on the Western Front. In contrast, his brother Charles James Saurin would fight with the Irish Volunteers in the Dublin Metropole Hotel during the Easter Rising of 1916. Twenty-four past pupils, some possibly classmates of Michael Wall, would fight with the Irish Volunteers and others in the Easter Rising.13

Like all recruits, Michael underwent a medical examination. He was examined by Lieutenant Colonel Dr M. O’Connell of the RAMC. Michael’s medical report noted that he was a healthy young man but had suffered from typhoid and diphtheria in the past. The report also noted that he was eighteen years of age. This was wrong, of course; he was in fact seventeen years, nine months and four days old, and so underage for military service.14 His application for a commission in the regular army was turned down, and he was told to reapply for a commission in the Reserve of Officers. Three days before Christmas 1915, Michael completed Army Form B.201, an application to the Special Reserve of Officers. His choice of unit was the Royal Irish Regiment. Because he was under twenty-one years of age, his mother had to sign the form as his guardian. Attached to the application was a Certificate of Moral Character signed by Fr Robert Carrick. His school principal at O’Connell CBS also signed a statement saying Michael had obtained a ‘good standard of education’.15

Christmas 1915 at Carrick Hill passed happily for Michael and his family. On 8 January 1916 Michael received a letter from Captain Cecil Stafford, writing on behalf of the assistant military secretary, Irish Command, at 32 Nassau Street, Dublin. The letter invited Michael to attend an interview at the headquarters of the 25th Reserve Infantry Brigade. The interview took place at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham, some time between 10.30 a.m. and 3.30 p.m. on 13 January 1916. The invitation noted that ‘owing to the large number of candidates registered, no undertaking as to your appointment to a Commission can be given or implied … No claim for travelling or other expenses in attending the Board can be sanctioned.’16

There was, indeed, a large number of applications from young, enthusiastic Irishmen just like Michael, who wanted to be officers. In fact, by 14 December 1914 Lieutenant Colonel W. B. Rennie, a senior staff officer with the 16th (Irish) Division, informed Sir Maurice Moore that ‘in junior officers, the division is already over establishment’.17

Before February 1916 one method of appointing officers was through self-appointment from amongst the ranks of men in their battalion, simply on the grounds of their standing in society. This created tension in some battalions, particularly the 7th RDF. Bryan Cooper notes that men found it difficult to work under their peers: ‘The preservation of rigid military discipline among men who were the equals of their officers in social position was not easy.’18 The main danger of this self-appointing system was that men with no military training or experience were given positions of command. Take Ernest Julian for example, a barrister educated at Trinity College, Dublin. He enlisted and was ‘Elected to Commission’ by his comrades in September 1914. He was commissioned a lieutenant one month later.19 Another example is Robert Douglas, who was educated at the grammar school in Kingstown and The Abbey in Tipperary. Like Julian, he was elected for a commission by his comrades in ‘D’ Company of the 7th RDF simply because ‘he had been known to most of them in sport’.20Poole Hickman was another Trinity graduate and a barrister on the Munster circuit before the war. On 22 September 1914 he was gazetted a second lieutenant in the 7th RDF, was made captain on 7 January 1915 and from that date was officer commanding ‘D’ Company 7th RDF. In fewer than six months, this man transferred from being a civilian barrister on the Munster circuit to commanding a company of soldiers on their way to war.21

This internal appointment of officers proved disastrous in combat, and lessons were learned at the War Office in London as to the consequences of self-appointed temporary commissions. According to Ian Beckett and Keith Simpson, ‘as a result of increasing subaltern casualties and the continuing expansion of the army, the War Office decided in February 1916 to establish a new system for selecting and training junior officers’.22The new system resulted in the formation of the Officer Cadet battalions set up throughout the United Kingdom.

However, in Ireland, Cadet Company No. 7 was established at Moore Park in Cork as early as November 1914.23 Up to 5 December 1915 the general officer commanding (GOC) of the 16th (Irish) Division was Lieutenant General Sir Lawrence W. Parsons.24A disciplinarian, Parsons also knew of the tragic consequences of internally appointing officers. To become an officer in the 16th (Irish) Division would demand dedication. In November 1914 Parsons left no young man in any doubt as to what was required of him:

If he (the applicant) has not had any previous military training, I tell him that he must enlist as a Private soldier in the 7th Battalion Leinster Regiment in which ‘C’ Company is kept as the Candidates Company … I tell him plainly that if I do not consider him fit for Officer’s or NCO’s [non-commissioned officer’s] rank he will have to go on service and, possibly die in a trench, as a Private.25

According to Lieutenant Colonel Frederick E. Whitton, ‘several hundreds of young officers were gazetted from time to time to various regiments’ from the 7th Leinster’s Cadet Company No. 7.26 Between November 1914 and December 1915, some 161 young men were commissioned from this company at Blackdown Camp near Aldershot.27

To be accepted into a cadetship, applicants first had to sit an interview with a senior officer. Michael Wall received his cadetship through this method when he met Captain Cecil Stafford at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham. His interview went well; on 15 January he received a letter from Captain Stafford stating, ‘I have the honour to inform you that your application for a Special Reserve Commission has been forwarded to the War Office.’28 Ten days later Michael received his letter of appointment (opposite) from the War Office informing him that he had been offered a commission as a second lieutenant in the Special Reserve of Officers and was posted to the 3rd Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment, at Richmond Barracks in Dublin.29

On 2 February 1916 Michael became a member of Class 12 and began a six-week course at the Dublin University Officers’ School of Instruction. Before he presented himself at the school, he was informed in a letter from the commandant that:

Letter from the War Office offering Michael a commission as a second lieutenant (on probation) to the 3rd Royal Irish Regiment,

25 January 1916.

Dublin University OTC Standing Orders for Class 1.

Officers will be billeted during the course and need not bring bedding, special billeting allowances is [sic] granted. Officers must report in uniform, swords are not necessary. Officers should bring with them the following books. Musketry Regulations, Infantry Training, Field Service Regulations Part 1 and The Manual of Map Reading.30

While with the Dublin University Officers’ Training Corps (OTC), the trainee officers were billeted in local hotels and had to obey a set of standing orders (opposite) on topics such as the maintenance of discipline in their hotel, eating and dress.31

The seduction of a uniform, status and future adventure had won the battle between Michael’s heart and his head.

Michael in uniform. Courtesy of the Kavanagh family.

3 ‘Fancy the Royal Irish captured Moore Street’

Towards the end of March 1916 Michael finished his six-week training course at the Dublin University OTC and was sent for further training to Ballykinlar, County Down. For Michael and his fellow trainees, the wooden billets at Ballykinlar were a far cry from the comforts of a plush hotel in the centre of Dublin. On 18 April Michael began a process of regular letter writing to family and friends. He wrote to his younger brother Bernard, who had just made his First Confession. Michael was pleased to hear the news that young Bernard was going to become a soldier. Not a British soldier, but, as all first confessors are told, a soldier of Christ. Michael promised to bring home his rifle and bayonet to show to Bernard.1

Michael spent Holy Week 1916 at home in Carrick Hill. On a rainy Easter Sunday morning, he left to return to Ballykinlar. He caught the Great Northern train from Amiens Street Station in Dublin and arrived back in camp in the early hours of Easter Monday morning. He missed the beginning of the Easter Rising in Dublin by one day. Had he been in Dublin, he would have been called up. He wrote to his mother on Tuesday:

Group of officer cadets at Ballykinlar Camp, County Down in April 1916. Michael is standing third from the left. Courtesy of the Kavanagh family

Officers Company

Ballykinlar Camp

Co. Down

April 25th 1916.

Dear Mother,

I arrived here quite safe about 1 oc[lock] on Monday morning. We stopped in Newry and had supper with a fellow called Frank, his father is a Veterinary Surgeon there. Do you know who has just got a commission in the R.A.M.C. – Willie O’Neill … I hear there was a great racket in Dublin with the Sinn Feiners and that there was some damage done to the post office. I have not seen any papers yet so I cannot say that it is true. It poured rain all the way back on Sunday from Drogheda and it is still raining … When are you going to the opera? Write and tell me if it was any good. I am sending a few cigarette pictures, I suppose Bernard will be pleased to have them. Do you know what you might do – send me on every Saturday night’s Herald as they publish the Roll of Honour of the different schools. Must close now. Give my love to Auntie and all at C. H.

I remain, your fond son,

Michael.

Please excuse scribble as I have a bad pen.2

The letter shows that the Rising came as a surprise to Michael, as it did to many of the people of Dublin. It is interesting to note that it is only the third item he refers to in his letter, after the supper with Frank and news about Willie O’Neill obtaining a commission in the RAMC.

However, reflecting the general change in the public attitude when the full impact of the Rising was realised, it became the first item in his next letter home. Indeed the excitement of the unfolding events may explain why Michael incorrectly dated this letter to 6 April (he probably meant 6 May). His ambivalent attitude had also changed:

Officers Company,

Ballykinlar Camp,

Co. Down.

April 6th [sic] 1916.

Dear Mother,

I hope this letter finds you all well and safe at Carrick Hill. Wasn’t it a terrible week. I hope Auntie has not sustained any damage as I saw in the paper that there was an outbreak at Swords but whether it is true or not I cannot say. I got back to camp too soon. I wish I had been in Dublin. It would have been great. Fancy the Royal Irish captured Moore St under Col. Owens. One of our officers was killed – Lt. Ramsey [sic] – I am sure Mrs Clifford must have been in a terrible state. About six hundred of the Rifles left here on the Tuesday after Easter and they held the Railway embankment at Fairview. Have you been to see poor old Dublin yet. There are a good many of our fellows gone up to Dublin for the weekend armed to the teeth with revolvers. Of course they had to motor up. The bugle sounded the alarm Saturday morning at one o’clock and we had to turn out as quickly as possible. I managed to get out in five minutes with my clothes on anyway and a rifle and bayonet. Some fellows ran out in their pyjamas. Then we were served out with fifty rounds of ammunition each and we were told that a party of Sinn Feiners had left Newry and were coming on to Newcastle with the intention of attacking the Camp. Then we started off and posted pickets and sentry groups and barricaded all the roads. That brought us up to 6:30 a.m. Then we had breakfast after which we were to fall in at eight o’clock. This gave us an hour’s rest and we all set to sharpening our bayonets on the door step. I have got an edge on mine like a razor. At eight o’clock, a portion of our platoon went off to dig a trench overlooking Dundrum and my party were sent out with wire cutters and gloves and we put up barbed wire entanglements and then occupied the trenches. We were relieved at 8 o’c[lock] p.m. but had to stand by so I was up for two nights and days. But we were sorely disappointed as the beggars never came out at all. Of course we were confined to camp up to Wednesday last and now we can go about freely enough. As soon as the train service is restored I will try and go up. I would like to see Dublin. I suppose Joe barricaded the house and had his air gun ready. What about Cyril and Bernard? Have they gone back to school yet. I saw Mrs Fogarty of Artane House in Newcastle on Wednesday and there are a couple of fellows here very keen on Miss Fogarty. I hope this letter will reach you all right, I’m sure it will as I see the Rotunda Rink is made into a post office. I must close now but I hope to hear from you soon. Give my love to all at Carrick Hill and kindest regards to Auntie.

I remain, your fond son,

Michael.3

News about the Rising in Dublin was slow to reach the front lines in Flanders, France and beyond. The authorities did their best to contain the news.4 The Irish serving overseas heard about the Rising in various ways. Private George Soper, a signaller serving with the 2nd RDF in France, read about the Rising in an Irish newspaper.5 Like Michael, Private Soper may well have read The Irish Times, which printed three editions during the week of the Rising. While serving with the Royal Artillery in Mesopotamia, Tom Barry found out about the Rising from a bulletin posted in his unit’s orderly room. He found the news ‘a rude awakening’.6Soon after the Rising, Irish papers reported that Irish troops felt betrayed and angered. Some of the nationalist newspapers gave their support to the Irish regiments that put down the Rising. On 5 May 1916 The Freeman’s Journal sang their praises:

Not regiments of professional soldiery of the old stamp, but reserves of the Irish Brigade who had rallied to the last call of the Irish leader, true Irish Volunteers … defending their city against the blind self-devoted victims of the Hun.7

German newspapers were aware of the Dublin rebellion and this news travelled to their troops at the front. They raised placards opposite the Irish lines informing them of the rebellion. One read: ‘Irishmen! Heavy uproar in Ireland: english guns are firing at your wifes and children! 1st May 1916.’8 The placards asked the Irish to desert, but little heed was paid to the German enticements. The war diarist of the 9th Royal Munster Fusiliers recorded a revenge taunt on 21 May, when his battalion hung up an effigy of Roger Casement in full view of the German trenches. The battalion’s war diary recorded that the effigy ‘appeared to annoy the enemy and was found riddled with bullets’.9

The Easter Rising could be argued to be the beginning of the Irish Civil War. The Freeman’s Journal thought so. Captain Stephen Gwynn, a nationalist MP serving with the 6th Connaught Rangers, noted that the 10th RDF, who fought the Irish Volunteers at the Mendicity Institution building during the Rising, included men who ‘had been active leaders in the Howth gun-running. It was not merely a case of Irishmen firing on their fellow countrymen: it was one section of the original [Irish] Volunteers firing on another.’10

Feelings about and reactions to the Rising varied among the thousands of Irishmen serving at the time in the British Army at home and at the front. There were feelings of surprise. Private Soper wrote to Miss Monica Roberts in Stillorgan in Dublin on 20 May 1916: ‘I was more than surprised when I heard of the Rebellion in Ireland and I could scarcely believe it until I read it in the papers …’.11 Michael Wall, as his letter revealed, was also surprised, and delighted to learn that his regiment had taken Moore Street from the rebels.12

Others felt angry and wanted revenge. On hearing news of the Rising, Lieutenant Patrick Hemphill speculated on 29 April: ‘I suppose they’ll hang the ringleaders. It’s what traitors deserve. It appears to have been got up by Roger Casement.’13 Michael told his mother that he was ‘sharpening’ his bayonet ready for any encounter with ‘the beggars’ in Sinn Féin. This young, middle-class Catholic Irishman, educated by the Christian Brothers in St Joseph’s and O’Connell School in Dublin, was totally against the Rising.14

Michael’s anger would later turn to a desire for retribution. Almost a year after the Rising, he reckoned that ‘those Sinn Feiners should be sent out here [to the front] to do a few nights on the fire step, I will guarantee it will cool their air down.’15 Private Christy Fox of the 2nd RDF, from North King Street in Dublin, felt the same way as Michael. He remembered the poverty in Dublin following the strikes in 1913 during the Lockout. Writing to Monica Roberts in Dublin, Fox noted:

I am glad to hear all the trouble is over in Dublin. I would like to have a few of those rebels out here, I can tell you I would give them 2 oz of lead. But in ways the poor fools, that’s what I would call them, were dragged into it by Connolly and a few more of his colleagues. Deed [sic] I know them very well, the lot of robbers. I remember the strike in Dublin, look at the way Dublin was left poverty stricken that time. It is the same click [sic] that has brought on all that destruction on our dear old country. However they are put down now and I only have one hope and that is I hope they are down forever.16

Such sentiments were common amongst the ranks of the 2nd RDF in France. Writing to Monica Roberts on 11 May 1916, Private Joseph Clarke told her what he and many of his comrades felt about the Rising:

I was sorry to hear of the rebel rising in Ireland, but I hope by the time this letter reaches you, the condition will have changed and things [are] normal again. There is no one more sorry to hear of the Rising than the Irish troops out here, it worries them more than I can explain. Their whole cry is, if they could only get amongst them for a few days, the country would not be annoyed with them anymore. Some of the men in this battalion is [sic] very uneasy about the safety of their people and one or two poor fellows have lost relatives in this scandalous affair. We just have had some men returned off leave and they tell us that Dublin is in ruins. It is awfully hard to lose one’s life out here without being shot at home.

The Sherwood’s [sic] lost heavily but I expect the Rebels got the worst of the encounter. We of the 2nd Battalion, the Dublins, would ask for nothing better that [sic] the rebels should be sent out here and have an encounter with some of their ‘so called Allies’, the Germans. I do not think anything they have done will cause any anxiety to England or her noble cause. We will win just the same. These men are pro-German pure and simple, and no Irish men will be sorry when they get justice meted out to them, which, in my opinion, should be death by being shot.17

Men feared for the safety of their families back in Ireland. Private Andrew Lockhart of the 11th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, a battalion in the 36th (Ulster) Division, was worried that the Irish Volunteers would cause trouble around his home farm near Bruckless in County Donegal. Writing to his sister Mina in Donegal he noted: ‘I was glad to hear that things are getting quiet in Ireland, had you any trouble with them at home …’.18

Private Christy Fox was initially very worried because he had not received any letters from home following the Rising. Since he lived near the Linenhall Barracks in Dublin, he was worried that his family had been caught up in the fighting. However, by the end of May 1916 he had received word that all was well. Writing to Monica Roberts, he noted:

I’m glad to be able to tell you I have got news from home, all my people are quite safe. There was [sic] a few people killed where I live. Those two men that were dug up in the cellar in 177 North King Street, I live in the house facing it at the corner of Linenhall Street. There were four men killed in a house only three doors from me at 27 North King Street, I live in 24 when I’m at home and I knew one of them well.19

One thing soldiers in any army must feel is that they have support from the home front. Loss of that support creates uncertainty in the ranks. According to Captain Stephen Gwynn, the Rising left Irish soldiers ‘in great measure cut off from that moral support which a country gives its citizens in arms’.20 Nationalist officers in particular believed the Rising was a betrayal and that it damaged the prospects of Irish Home Rule. Gwynn told his fellow nationalist MP Major William (Willie) Hoey Kearney Redmond (who, incidentally, was Michael Wall’s commanding officer in the 6th Royal Irish Regiment): ‘I shall never forget the men’s indignation. They felt they had been stabbed in the back.’21 According to Jane Leonard, ‘Captain Stephen Gwynn’s subsequent speeches to the House of Commons and his letters to the press were bitter about the damage done to Home Rule.’22

Willie Redmond, who had been on leave in England at the time of the Rising, in turn, wrote to Gwynn: ‘Don’t imagine that what you and I have done is going to make us popular with our people. On the contrary, we shall both be sent to the right about at the first general election.’ Redmond, who was also devastated by the fighting in Dublin, clearly feared he would lose his seat in the next election. It was Patrick Pearse’s appeal to the ‘Gallant German allies’ that particularly shocked him.23 The Rising had undermined his political life’s work. His wife wrote that ‘often since the rebellion he said he thought he could best serve Ireland by dying’.24

Irish Nationalist MP and officer in the 9th RDF Tom Kettle was also aghast at the Rising. He denounced the venture as madness, seeing it as destructive of what he had striven for throughout his adult life.25

Following the execution of leaders of the Rising between 3 and 12 May, attitudes of some of the civilian population began to change in favour of Sinn Féin. Robert Barton, a Wicklow landowner, was gazetted from the Inns of Court OTC to the RDF just as the rebellion began. As a soldier he experienced that change in civilian sentiment. By June 1916 he noted that ‘everyone is a Sinn Feiner now … Ireland will never again be as friendly disposed to England as she was at the outbreak of the war’.26

Some of the soldiers also started to question whether they had made the right choice in joining the British Army. They may well have felt disillusioned. Men like Second Lieutenant O’Connor Dunbar of the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC), a friend and colleague of writer and poet Monk Gibbon, who wrote about Dunbar’s participation in the gun-running at Howth and was a Redmondite National Volunteer. Gibbon, who was also an officer in the RASC, stated that ‘it had taken the Easter executions to make Dunbar begin to doubt the wisdom of the step he had taken’.27

Like Michael Wall, Charles Duff had just missed the Rising, going to England for officer training on Easter Monday from Fermanagh. He noted in his memoirs that he ‘had joined the British Army as a volunteer in Dublin – to fight Germans’, but presumably not to fight his fellow countrymen.28 Tom Kettle was also distressed by the executions; he was friendly with several of those who were shot. Moreover, the murder of his brother-in-law, Francis Sheehy Skeffington, during the Rising deeply affected Kettle. Kettle’s wife, Mary, and Francis’s wife, Hannah, were sisters. Sheehy Skeffington’s murderer, Captain Bowen-Colthurst, and Kettle wore the same uniform. Kettle, too, began to doubt his vocation.29

Writing in 1970 about ‘that affair in April 1916’, William Mount, an ex-officer with the RDF and friend of Seán Heuston (who had commanded the Volunteer garrison in the Mendicity Institution), stated, ‘there were times when I wondered if we were on the right side’. Referring to the executions he said, ‘That was a cowardly, unforgivable thing to do.’30 John Lucy of the 2nd Royal Irish Rifles was anguished by the news of the executions. He noted that ‘my fellow soldiers had no great sympathy with the rebels but they got fed up when they heard of the execution of the leaders’.31 The poet Francis Ledwidge was also deeply troubled by the executions in Dublin: ‘Yes, poor Ireland is always in trouble,’ he wrote to an Ulster Protestant friend on the day the first leaders were executed. ‘Though I am not a Sinn Feiner and you are a Carsonite, do your sympathies not go to Cathleen ni Houlihan? Poor MacDonagh and Pearse were two of my best friends and now they are dead, shot by England.’32

Some nationalist-minded men felt powerless, realising that they could do little more than get on with the task in hand at the front. Lieutenant Michael Fitzgerald, serving in the Irish Guards, noted: ‘We were too preoccupied with what was in front of us and what we had to do … whatever might happen in Ireland after we’d gone we could do nothing about it. That was our attitude.’33Others found the whole affair uninteresting. Anthony Brennan of the 2nd Royal Irish Regiment wrote in 1937: ‘Although we were mildly interested, nobody took the thing very seriously.’34