10,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Southbank Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

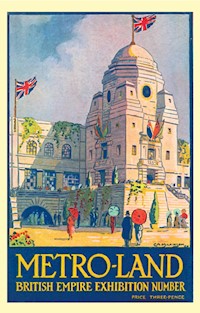

Metro-land was published annually from 1915 until 1932 featuring evocative descriptions and photographs of historic villages and rural vistas of the areas served by the Metropolitan Railway This 1924 edition was published just as the property and leisure boom was under way and also had the extra purpose of promoting The British Empire Exhibition of 1924 at Wembley,

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

METRO-LAND

1924 edition with a new introduction from

Oliver Green

INTRODUCTION

A detail of a decorative poster map of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley issued by the Underground Group in 1924. Cartography by Thomas Derrick, illustration by Edward Bawden.

AN INTRODUCTION TO METRO-LAND

Metro-land is the creation of the Metropolitan Railway’s Publicity Department. The title was devised as a catchy marketing brand name for the areas north west of London in Middlesex, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire served by the line. It first appeared in print in 1915 with the publication of Metro-land, a guidebook designed to promote the area for leisure excursion travel from London. More significantly, Metro-land was intended to stimulate new residential development, populating these districts with middle-class commuters who would travel to and from London daily on the Metropolitan’s services. Launching a promotion like this during the First World War, when house-hunting was hardly a priority for many people, does not look like the best of timing. But the essence of the scheme was to blossom into a huge success in the post-war twenties, when new suburban house sales around London took off as never before. The 1924 edition of Metro-land reproduced here was published just as the boom was under way.

A new edition of Metro-land was published annually from 1915 until 1932, the last full year of the Metropolitan’s existence as an independent railway company. On 1 July 1933, the Met unwillingly became part of London Transport, the new authority that took over all bus, tram and underground railway services in the London area. The Metropolitan was downgraded from main line railway status to just one of London Transport’s seven underground lines. Metro-land was dropped immediately from the advertising vocabulary of the new Board, never to be used again in official publicity, although London’s suburban growth continued until it was ended abruptly by the outbreak of war in September 1939.

Early Metro-land promotion in action. Two of the Metropolitan’s wartime women workers posting Metro-land advertisements outside a rival company’s station (Cricklewood, Midland Railway) c 1917.

Metro-land may have lost its official standing only eighteen years after its invention, but the name had already entered the language as an almost generic expression of suburban life. A popular song called My Little Metro-land Home had been published in 1920. The word had even, through Evelyn Waugh’s fictional character Margot Metro-land, appeared for the first time in the pages of a novel (Decline and Fall, published in 1928). Metro-land’s characteristics were later to be affectionately evoked in the poems of John Betjeman, such as The Metropolitan Railway (1954) and in his nostalgic BBC television programme, Metro-land, made in 1973. Yet another perspective appears in Julian Barnes’ first novel, Metroland (1980), where the writer draws on memories of his own suburban upbringing in the area in the 1960s. For Barnes, ‘Metro-land is a country with elastic borders which every visitor can draw for himself, as Stevenson drew his map of Treasure Island’. In little more than half a century, Metro-land grew from being an ad man’s creative invention into a more prosaic reality in the 1920s and 30s, a wistful post-war recollection from the 1950s onwards and finally a new land of personal imagination by 1980.

The area that was christened Metro-land in 1915 had been opened up by the railway between 1880 and 1905. In the process, the Metropolitan was itself transformed from a short urban underground feeder line linking three London termini with the City, into a fully fledged long distance railway with main line aspirations. The original section of the Metropolitan, opened in January 1863 between Paddington and Farringdon, was the world’s first underground railway. It was gradually extended over the next twenty years until, by linking up at both ends with London’s second main underground line, the District Railway, the Inner Circle (now the Circle line) was completed in 1884. By this time, the Metropolitan was concentrating its resources on promoting a potentially more lucrative expansion out into the country through London’s north west suburbs. This began as a modest branch line from Baker Street to Swiss Cottage, originally called the Metropolitan and St. John’s Wood Railway, which opened in 1868. The railway was then pushed overground through green fields on the edge of London, beyond Finchley Road to Willesden Green (1879), Harrow (1880), Pinner (1885), Rickmansworth (1887) and Chesham (1889). Chesham became a branch terminus when the main line was built onwards from Chalfont Road (now Chalfont and Latimer) through Amersham to Aylesbury (1892). A link with the existing Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway took Metropolitan trains on to Verney Junction, a remote country station in north Buckinghamshire, where there were connecting services on other lines to Banbury, Bletchley and Oxford.

An early edition of Metro-land c 1916.

Through Metropolitan services from Verney Junction to Baker Street were introduced in 1897. A short branch from Quainton Road to Brill, built by the Duke of Buckingham to serve his private estate, was also acquired by the Metropolitan in 1899. Thus, by the turn of the century, the Metropolitan’s domain stretched over more than fifty miles from central London through the Chilterns into deepest Bucks. At the time, this was less about preparing the ground for suburban development than the initial building blocks of a far grander plan by the company chairman, Sir Edward Watkin. His ambition was to make the Metropolitan the key link in a main line network running from Manchester via London to Dover, then through a proposed Channel tunnel to Paris and the rest of Continental Europe. This was no idle dream. Watkin was already chairman of two other existing railway companies along the route as well as the nascent Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway, which was planning a new trunk line from the north west to London. He was one of the most powerful and influential of the late Victorian railway barons, but a debilitating stroke forced him to resign as Metropolitan chairman in 1894. The company’s more grandiose and visionary plans effectively collapsed with him. Although the successful completion of a Channel rail tunnel was still a century away, other more modest development possibilities were already emerging for the Metropolitan.

As was often the case when a new railway opened, the Metropolitan’s Extension Line brought new residential development in its wake, although not always as quickly as the company would have liked. Unlike any other railway, however, the Metropolitan became directly involved in housing development itself, using surplus land alongside the line bought before the railway was built. Property not required for railway purposes was usually resold when construction was complete, but the Metropolitan cannily hung on to its purchases. The company’s first property development venture was the Willesden Park Estate, laid out on railway land near Willesden Green station in the 1880s and 1890s. The houses were modest, semi-detached villas intended for rental by middle-class families.

Another two housing estates, including some rather more upmarket residences, were begun in the early 1900s further down the line at Pinner (Cecil Park) and at Wembley Park, where a large area of land south of the railway had been acquired in 1890 to develop as sports and pleasure grounds. This was another Watkin scheme that included, as its centrepiece, plans for a massive viewing tower inspired by the success of the Eiffel Tower, built for the Paris Exhibition of 1889. The Wembley Park pleasure grounds were opened to the public in 1894, served by a new station, but the great tower had already run into financial and construction difficulties. It never rose above the first 155ft. high stage, a mere fifth of its intended stature. Without the main attraction, the hoped for crowds of trippers arriving on Metropolitan trains never materialised. Watkin’s Folly, as the part built tower became known, was eventually closed to visitors and finally demolished in 1907. Wembley had yet to become a household name.

During the Edwardian years, the ground was laid for the full-scale development of Metro-land that took place in the 1920s. The railway service was further extended and modernised with a new branch line from Harrow to Uxbridge, opened in 1904, and the start of electric services the following year over the inner sections of the Metropolitan and as far out as Uxbridge. Banishing steam locomotives from passenger trains on the Met’s sub-surface lines was not before time, as the unpleasant atmosphere of its stations and tunnels compared badly with the clean new rival electric Tube railways that were criss-crossing the capital. A sign of the new standards to which the company aspired was the introduction of two Pullman cars in 1910. These were used on some of the fast long-distance services to and from Buckinghamshire, providing drinks and light refreshments to first-class passengers paying a supplementary fare. Tea or coffee with buttered toast, cake and jam was available for 1s 6d (7½p), while a light breakfast, lunch or supper cost 3s 0d (15p). A full range of alcoholic drinks was also available from the bar.

Opening day special train on the Uxbridge branch at Ruislip. 30 June 1904. Public services began on 4 July using steam trains for the first six months. This locomotive, Met no. 1, is preserved in working order at the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre at Quainton.

Two luxury Pullman cars named Mayflower and Galatea were introduced on some long distance Met services in June 1910. This is the opulent interior of one of them.

Such luxuries were only taken up by a small proportion of the Metropolitan’s clientele. The Pullman service was more of an image builder than a profit maker, but other more significant improvements that could be appreciated and experienced by all the railway’s customers were being developed in this period. This was particularly true after the appointment of Robert Hope Selbie as General Manager in 1908. It was the autocratic but far-sighted Selbie who now drove a series of new initiatives for the Met and who would oversee the successful creation of Metro-land. Selbie recognised that promotion of new traffic for the railway had to go hand in hand with visibly improved services. A major investment in additional express tracks over the busy bottleneck section between Finchley Road and Wembley Park during 1913–15 was a prime example of this. Selbie’s additional proposals, to extend the electrification of the main line beyond Harrow to Rickmansworth and to build a new electric branch to Watford, had to be postponed with the outbreak of war in 1914. Further estate development was also brought to a temporary halt, although the optimistic launch of the first Metro-land guide only a year later showed that the railway had not shelved all its plans for the duration of the war.

In January 1919, only two months after the Armistice, a scheme was announced to create a new property company that would manage and develop the railway’s land holdings. Until this point, the commercial administration of the Met’s estates had been in the hands of the Surplus Lands Committee. The Committee’s responsibilities were now taken over by Metropolitan Railway Country Estates Ltd. Legally it was a separate company independent of the railway, but in practice the MRCE was under the control of the Metropolitan’s directors. Selbie, who was an MRCE director from the start, became a director of the Metropolitan Railway in 1922 whilst continuing to serve as its General Manager. It was a cosy arrangement that gave the Metropolitan the unique opportunity among railway companies to become a profitable property developer.

The 1920 edition of Metro-land.

Between 1919 and 1933, the MRCE developed a series of private housing estates all down the line at Neasden, Wembley Park, Northwick Park, Eastcote, Rayners Lane, Ruislip, Hillingdon, Pinner, Rickmansworth, Chorleywood and Amersham. In the early days, the estates company built some houses itself, but the usual pattern was to lay out an estate and then sell plots to individual purchasers wishing to have a house built to their own specifications. Later on, the design and construction was usually undertaken by other companies who would offer the prospective purchaser a choice of house sizes and styles at a range of prices. The procedure is described on pages 80 to 95.

A poster promoting the 1926 edition of Metro-land.

The annual Metro-land guide was always the main advertising medium for these developments. The seductive dream of a new home on the edge of beautiful countryside but with every modern convenience, including a fast rail service to central London, was an appealing vision eighty years ago, and remains so today. In true advertising tradition, the Met’s copywriters went way over the top in their purple prose, trying rather unconvincingly to blend notions of age-old rural tradition with civilised progress: ‘This is a good parcel of English soil in which to build home and strike root, inhabited from of old ... the new settlement of Metro-land proceeds apace; the new colonists thrive amain’. The language must have sounded contrived even then, although a quick glance today at the ads and features in the weekly Homes and Property supplement of the London Evening Standard will show that marketing methods have only changed superficially. Lifestyle advertising and promotion using fashionable jargon still seems to work. Metro-land was just one of the first and most successful examples of an approach to property marketing that is now familiar to us all.

Poster advertising the Met’s Country Walks booklets, mainly featuring rambles from the outer Metro-land stations beyond Amersham, 1929.

Until after the First World War, hardly anyone in Britain owned their own home. Before 1914, even the wealthier middle classes usually rented, but in the 1920s actually buying a new house with a mortgage became a practical possibility for thousands of people. Building societies, which provided most of the new mortgages for house purchases, did not require large cash deposits and loan rates were low. One of the fastest growing societies in the London area which helped finance the Metro-land boom was the Abbey Road, later to become the Abbey National, which registered a 700% increase in borrowers between 1926 and 1936. A prominent advertisement for the Abbey appears in this and most subsequent editions of Metro-land.

Every Metro-land booklet features evocative descriptions and photographs of historic villages and rural vistas in what its authors claimed to be ‘London’s nearest countryside ... where charm and peace await you’. Production and printing were of an exceptionally high quality, with the special luxury, for this period, of coloured covers and plates that could be ordered in sets for framing. No doubt the brochure conjured up a tempting prospect for the hiker or day tripper, but Metro-land’s real target market was always the prospective resident rather than the casual visitor. Selbie and his colleagues always had new season ticket holders in their sights. In the persuasive words of the 1920 edition of Metro-land, ‘the strain which the London business or professional man has to undergo amidst the turmoil and bustle of Town can only be counteracted by the quiet restfulness and comfort of a residence amidst pure air and surroundings, and whilst jaded vitality and taxed nerves are the natural penalties of modern conditions, Nature has, in the delightful districts abounding in Metro-land, placed a potential remedy at hand’.

As well as offering a guide to visitors and potential residents of Metro-land itself (the outer suburban and country area starting at Wembley), this Metro-land booklet purports to offer guidance to anyone travelling up to Town with a ‘How to get about London section’ on pages 25 to 34. Closer inspection reveals the bizarre recommendation that visitors start by memorising the position of the most convenient railway station for their destination (p28) linked to the misleading suggestion that as the Metropolitan ‘goes north, south, east and west’, there is always likely to be a Met station or interchange with the Tube close at hand. The Key Plans on pages 32 and 33 actually give a rather poor indication of the precise street locations of many central London Tube stations, which almost suggests a deliberate attempt to sabotage any use of rival Underground services. It is also curious that the photographs of the City on pages 30 and 31 are more than a decade out of date. They were clearly taken around 1910 when there were still horse buses on the streets. Is this a sly dig at another rival transport company, the London General Omnibus Company, which had in fact replaced its entire horse drawn fleet with new motor buses in 1911? If this is simply an oversight, it gives the photographs a strangely archaic feel, particularly alongside a text which is obsessively fixated on the modern features and up to the minute statistics of the Met’s new services to the forthcoming British Empire Exhibition at Wembley. Perhaps the simple explanation is that this 1924 edition of Metro-land has been rather uncomfortably adapted to squeeze in as much as possible about the new show at Wembley as this was clearly about to be the dominant attraction of the area in the year ahead.