8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

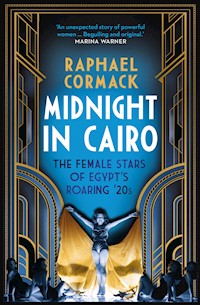

1920s Cairo: a counterculture was on the rise. A passionate group of artists captivated Egyptian society in the city's bars, hash dens and music halls - and the most dazzling and assertive were women. Midnight in Cairo tells the thrilling story of Egypt's interwar nightlife, through the lives of these pioneering women, including dancehall impresario Badia Masabni, innovator of Egyptian cinema Aziza Amir and legendary singer Oum Kalthoum. They exploited the opportunities offered by this new era, while weathering its many prejudices. And they held the keys to this raucous, cosmopolitan city's secrets. Introducing an eccentric cast of characters, Raphael Cormack brings to life a world of revolutionary ideas and provocative art. This is a story of modern Cairo as we have never heard it before.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

MIDNIGHTIN CAIRO

MIDNIGHTIN CAIRO

The Female Stars of Egypt’s Roaring ’20s

Raphael Cormack

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Saqi Books26 Westbourne GroveLondon W2 5RHwww.saqibooks.com

Copyright © Raphael Cormack 2021

Raphael Cormack has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

Map by Chris Robinson

Illustration on page 2: Publicity shot of Mounira al-Mahdiyya, courtesy of the Abushady Archive.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978 0 86356 313 3eISBN 978 0 86356 338 6

A full cip record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

CONTENTS

Introduction: The Past Is a Set of Old Clothes

Part I: SETTING THE SCENE

Chapter 1 ‘PARDON ME, I’M DRUNK’

Chapter 2 FROM QUEEN OF TARAB TO PRIMA DONNA

Chapter 3 ‘COME ON SISTERS, LET’S GO HAND IN HAND TO DEMAND OUR FREEDOM’

Chapter 4 DANCE OF FREEDOM

Part II: THE LEADING LADIES

Chapter 5 ‘IF I WERE NOT A WOMAN, I’D WANT TO BE ONE’

Chapter 6 SARAH BERNHARDT OF THE EAST

Chapter 7 THE SINGER, THE BABY AND THE BEY

Chapter 8 STAR OF THE EAST

Chapter 9 COME ON, TOUGH GUY, PLAY THE GAME

Chapter 10 ISIS FILMS

Chapter 11 MADAME BADIA’S CASINO

Part III: CURTAIN CALL

Chapter 12 THE SECOND REVOLUTION

Conclusion HOW TO END A STORY

Acknowledgements

Notes

Sources and Further Reading

Index

If you visit a city during the day, you cannot claim to know it. You have to see its nightlife.

JEANETTE TAGHERLes Cabarets du Caire dans la Seconde Moitié du XIXe Siècle

Ezbekiyya, Cairo’s nightlife district, in the 1920s.

MIDNIGHTIN CAIRO

INTRODUCTION

The Past Is a Set of Old Clothes

IN THE LATE 1980s, THE EGYPTIAN WRITER LOUIS AWAD looked back on his student days in Cairo between the wars. In particular, he remembered the nights he spent in the cafés of Cairo’s nightlife district, Ezbekiyya:

All you had to do was sit in one of the bars or cafés that looked out onto Alfi Bey Street, like the Parisiana or the Taverna, and tens of different salesmen would come up to you, one selling lottery tickets, another selling newspapers, another selling eggs and simit bread, another selling combs and shaving cream, the next shining shoes, and the next offering pistachios. There were also people who would play a game ‘Odds or Evens’, performing monkeys, clowns, men with pianolas who performed with their wives, fire eaters, and people impersonating Charlie Chaplin’s walk. Among all these, there was always someone trying to convince you that he would bring you to the most beautiful girl in the world, who was only a few steps away.1

In the 1920s and 1930s, the centre of nightlife in Ezbekiyya was Emad al-Din Street – long and wide, with a tram line down the middle running north to the suburbs of Shubra and Abbasiyya. The intersection with Alfi Bey Street, where Louis Awad used to sit in the bars and cafés, was at the southern end of the action. There stood the grand Kursaal music hall, owned by the Italian impresario Augusto Dalbagni, its two-storey entrance topped with stars and crescent moons to imitate Egypt’s flag, where touring European acts and local Egyptians alike performed. Down into Alfi Bey Street was an ever-changing series of venues, which in the early days of this area’s prominence included the grand Printania Theatre and, beside it, the Abbaye des Roses music hall. In the mid-1920s a new form of entertainment emerged when the venue became a court where the Basque sport of pelota – a ball game similar to squash or fives – was a popular late-night attraction with the main match starting at midnight.

Further north up Emad al-Din Street, the four grand domes of the khedivial buildings, finished in 1910, towered over the street from both sides. In this complex of apartments and offices, the Greek poet George Seferis used to work in the 1940s. In one of his poems he recalled the ‘car horns, trams, rumbling of car engines and screech of brakes’ that used to greet him on his walks.2 The street was lined with cinemas: the American Cosmograph, Empire, Obelisk, Violet and more. In the 1910s and ’20s they ran a selection of foreign films with intertitles (aka title cards) in French, English, Arabic and Greek and, sometimes, with live musical accompaniment – the Gaumont Palace featured a small orchestra led by the famous violinist Naoum Poliakine. Just before the junction with Kantaret al-Dikka, the street that led towards the red-light district to the east, was Youssef Wahbi’s Ramses Theatre, where his troupe put on a selection of Arabic tragedy, comedy and melodrama.

Across Kantaret al-Dikka, on the other side of the junction, was the European-style Casino de Paris cabaret. One Egyptian journal described it enthusiastically in 1923 as offering ‘exquisite Parisian girls, who come on stage to interpret the latest numbers from Paris, an agreeable atmosphere, fine champagne, and nothing lacking to give a total illusion of one of the Montmartre cabarets.’ A more cynical writer said that ‘with its walls hung with pink paper, its stage which is not much more than platform, and its bar of varnished wood . . . the Casino de Paris, in fact, much more resembled one of those small clubs that flourish in austere provincial towns, to the terror of the virtuous bourgeoisie.’ This infamous venue was run by Marcelle Langlois, a Frenchwoman with strikingly dyed red hair, who was notorious among anti-prostitution campaigners as a ‘procurer’ of chorus girls for wealthy clients. Her activities, both in and out of sight, earned her enough money to buy a large château in France.3

Emad al-Din Street, looking north.

Just past this European-style cabaret was a series of music halls and theatres that showed, in the words of one American journalist, ‘continuous three to five hour shows in Arabic and English . . . heavily peppered with bawdy jokes’ and catered to local Egyptians and occasional tourists. There were the Majestic, the Bijou Palace and the Egyptiana. In these theatres and music halls, the Franco-Arab revue flourished. It was a uniquely Cairene genre: a selection of short farces, songs and dances, all in a mixture of Arabic and French, bringing together in one night of entertainment Egyptian actors and dancers with performers from the music halls of Europe.4

Today, Emad al-Din Street has retained only traces of this world. There is just one theatre still working on the street, a derelict cinema stands on the site of the Casino de Paris, and the Scheherazade is the only major cabaret still operating in the area; the others have either moved out to Giza or behind nondescript doorways in the side streets of downtown Cairo. But in its heyday, Cairo’s nightlife could rival that in Paris, London or Berlin. Any resident of Egypt’s capital city in the early twentieth century could have claimed, with justification, to be living in one of the great cities of the world, at the centre of many different cultures.

The city’s population had come from an amazing variety of places across Europe, Africa and Asia. Some people (mostly the Europeans) enjoyed pampered lives with lucrative jobs in Africa’s latest boom town. Others struggled, working in menial jobs or negotiating the growing criminal underworld, trying anything to stay afloat. People seeking better opportunities lived alongside refugees from Europe who came in the wake of the First World War. Spies and political agitators from as far away as Russia and Japan crossed the paths of sybaritic aristocrats, who whiled away their afternoons in hotel bars.

This history of cosmopolitan Egypt is memorably recorded in the novels, poems and memoirs of Europeans, most of them living in Alexandria. From the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy’s melancholy evocations of Mediterranean café life to the rich, chocolate-cake prose of Lawrence Durrell’s epic Alexandria Quartet, these writers created some of the most enduring images of twentieth-century Egypt. But, far from the elite literary salons of Alexandria, another story unfolded – less well known but just as exciting – in the Arabic theatres, cafés and clubs of Cairo. In the transgressive nightlife of central Cairo, with all the freedom that came with performing for an audience of strangers, rigid identities and conventional barriers that separated different nationalities were more fluid than anywhere else.

Even a cursory attempt to list the stars of this period reveals the huge variety of their backgrounds, whether religious, national or cultural. Some became legends, others have been forgotten, but they all played their part. There were Egyptians of all kinds. Many of the earliest star actresses, like Nazla Mizrahi or the Dayan sisters, were Jewish; others were Christian or Muslim. Some performers came from further up the Nile. One dance hall in the 1930s boasted a troupe of Sudanese dancers, and among the many young actresses trying to break into the big time in the 1920s was Aida al-Habashiyya, who, to judge from her name, must have been of either Ethiopian or Sudanese descent (Habasha is the Arabic word for that part of sub-Saharan Africa). Other dancers, singers and actors came to Cairo from all over the Arab world to perform on its stages. Europeans, too, populated this primarily Arabic-speaking world. One of the most famous dancers of the 1920s was the Englishwoman Dolly Smith, who worked as a choreographer for the biggest theatrical companies in Cairo. Then there was the French Madame Langlois, the influential cabaret impresario and owner of Cairo’s Casino de Paris. The life of the stage proved a magnet for ambitious misfits of all kinds. They found ample possibilities in the nightlife district of Ezbekiyya, where the refined opera house and expensive hotels sat alongside smoky bars, hashish dens and nightclubs; where Greek waiters served their artistic patrons coffee, wine and zabib (a potent Egyptian version of arak); where singing and dancing lasted long into the night.

The story of this world from the late nineteenth century to the 1950s is often mythologised in Egypt but largely overlooked in the West, where the Middle East is usually seen only as a political problem to be solved. Yet it is full of surprises. It includes, at different points, a gay English Arts and Crafts designer, several cross-dressing actresses, a belly dancer involved in underground left-wing politics, and an unsuccessful attempt to make a film version of the life of the prophet Muhammad, directed by the man who went on to make Casablanca. Offstage, the action is punctuated by lawsuits, murder and revolution.

It should come as no surprise that early twentieth-century Cairo was full of so much drama. Egypt, at the time, was a country on the verge of huge social and political change. In 1919 a generation-defining series of events was set into motion; Egyptians had revolted against British colonial rule and, as a result, Egypt became officially independent (albeit with significant British control remaining, as we shall see). After this, they began to ask themselves what they wanted their country to be and what their future could look like as new beliefs and ideologies jostled for space.

The new generation debated big political ideas: liberalism, communism, atheism and more. In a 1941 film called Intisar al-Shabab (The triumph of youth), the main character caught the mood of the times: ‘That past is a set of old clothes; take it off and throw it away.’ Everywhere people were talking about this Nahda or ‘renaissance’ and the new opportunities it was heralding. The 1920s and 1930s were an exciting time to be alive in Egypt.

It was in this atmosphere of revolutionary ideas and change that the feminist movement in Egypt grew and expanded. In the early twentieth century, a number of organisations and unions were set up to support women’s rights; magazines were established that gave women space to discuss the issues that affected them directly; books on female progress and liberation were published. Egyptian women became part of a movement for change that took advantage of new technologies and a new feeling of internationalism to promote these ideas across the globe.

The conventional history of early twentieth-century Egyptian feminism usually runs through a list of prominent female activists, most (if not all) from middle- or upper-class backgrounds – Hoda Shaarawi, Nabawiyya Musa, May Ziadeh, Ceza Nabarawi, and the Egyptian Feminist Union. The brand of progress they advocated was cautious and incremental. They published magazines, attended international conferences, promoted women’s education and campaigned for women’s political rights, but they were careful not to make men too uncomfortable. Men, in turn, gave lip service to these new feminist ideals but maintained and protected their own male spheres of influence. High politics remained almost exclusively a male domain, as did high literature. Literary men professed their commitment to equality but spent their long evenings in the cafés, pontificating about art and beauty without any women present. The few female writers to enter these closed literary circles were exceptional.

However, outside of this world, another history of Egyptian feminism was being written on the stages of Cairo’s nightclubs, theatres and cabarets. The women’s movement in Egypt is not usually seen from the perspective of music hall singers, dancers and actresses. They lived in the margins of so-called decency, and hardly anyone who saw themselves as respectable wanted to be publicly associated with them.

British visitors, missionaries and colonial administrators saw these women as embodiments of all the old stereotypes they had about Egyptian society – primitive, exotic and pleasure-obsessed – further evidence that Egypt was not yet a nation capable of ruling itself, and either dangerously erotic or there to be saved. Meanwhile, members of Egypt’s elite class of modernising nationalist politicians and intellectuals, who were trying to show that they were capable of self-governance, were no more pleased than the British with the dance halls and nightclubs in their capital. They saw them, though, not as signs of their country’s own backwardness but as one of the many corrupting forces imported from the West. The bars, cafés and dance halls of Cairo, and particularly the female entertainers who filled them, were dragging the nation down and bringing the bright prospects of a new generation down with them.

Yet, in these disparaged music halls and theatres, women were defining their own place in the new century. They had a lot to fight against, from the disapproval of conservative society to men who thought they could do what they wanted with an actress or nightclub singer. But the lucky ones who managed to navigate their way through this world achieved significant personal and financial independence. Female singers commanded large audiences; actresses were in high demand; women owned dance halls, wrote and directed films, and recorded hit songs. In 1915, eight years before the founding of the Egyptian Feminist Union, the singer and actress Mounira al-Mahdiyya formed her own theatrical troupe.

These women who did so much to create modern Egyptian culture were not part of the elite. They frequently grew up in poverty, and many had little formal education – often they had to learn how to read just to be able to understand the scripts for plays they were supposed to act in. Nonetheless, telling the history of Egyptian culture – of Egypt itself – would be impossible without them. They chose what to perform and the Egypt they wanted to show. This is the story of a parallel women’s movement, one that happened in the demi-monde, late at night after the high-class critics had gone to bed.

Despite their lack of respectability (or perhaps because of it), these women soon became the first modern Egyptian celebrities. In the 1920s a series of popular entertainment magazines came into being, all of them catering to fans obsessed with these female stars. Journalists dissected everything about them, publishing countless photos, interviews and articles, feeding the public demand for details of their favourite stars’ lives. Later in life, many of these women also published their own memoirs of this period, often casting themselves in the best light or settling old scores. In this celebrity story-mill, fuelled by gossip, romanticism and myth, tales often took on a life of their own – the more flamboyant the better. Yet at its core, this was a group of women demanding to be heard as they asserted their wishes, claimed their rights, and made space for themselves.

Women offered a perspective on this world that men could not – and it was one in which men often came across quite badly. In 1951 a veteran actress called Fatima Rushdi wrote an article explaining why she loved acting parts written for men. She argued that such roles as Romeo, Hamlet, Napoleon and Don Juan ‘suit a woman’s nature because they have a universal character. They have a certain subtlety and intelligence that only she can succeed in capturing.’ Women, she argued, with their sensitivity to the world around them, just make better actors – whether the part be male or female. ‘Men have been luckier than women in the acting profession, but women are better actors,’ she said, contending that ‘only a woman can really get to the depths of the characters’. She concluded that ‘to put it plainly, women can give a performance that is more complete and successful than any man’.5

Since my first visit to Egypt in 2009, I have gone back and forth more times than I can count – first to learn Arabic, then to work on a PhD on adaptations of Sophocles’s tragedy Oedipus Rex in modern Egyptian theatre, and finally to research this book. Cairo is a city whose history feels, physically, very present – from the tombs around Imam al-Shafii’s mausoleum to the mosques and madrasas of the old walled city. I have always gravitated towards downtown, the heart of the modern city away from the historic centre, and wondered what stories also lurk there. What would it have been like to walk the same streets a hundred years ago?

While writing my PhD, I discovered that an abundant, animated and spirited entertainment press existed in 1920s and 1930s Egypt. Some of these magazines are still well known in Egypt; others seem to exist only in the collections of the National Library of Egypt; all of them are filled with bizarre and offbeat stories of Cairo’s wild nightlife and the stars of its entertainment world. There was, as one might expect, a good amount of gossip and rumour; but it was enough to send me on a mission to find out more. I soon discovered that a lot of the celebrities from that period had written memoirs (some had written more than one set) that were equally full of amusement and intrigue. After reading some more academic works of history on the period and searching through archives across the world, I managed to build a history of Cairo’s modern, cosmopolitan nightlife, a scene that was enticing and seductive but also exploitative and dangerous.

This book is my attempt to shine a light on that history and to show how Cairo became one of the most exciting cities in the world for anyone to spend a night in during the early twentieth century. This is a theatrical story in three acts. The first act tells the eventful modern history of Egypt’s nightlife from the late nineteenth century until the 1920s, alongside the wider context of colonialism, war and revolution. The stars of the second act are a few of the most important, successful and influential women of Cairo’s 1920s entertainment industry. With careers that often lasted several decades, spanning theatre, music, cabaret, film and journalism, their lives were entangled and intertwined both professionally and personally. Delving into the complex, well-lived lives of these seven exceptional women, this act returns them to the limelight after almost a century. The final act recounts Ezbekiyya’s journey through the Second World War to its final days as the centre of Cairo’s nightlife as Egypt moved into a new, post-colonial era with Nasser’s revolution in 1952. Together, these three acts tell an overlooked story of theatre, song and dance that shows the modern Middle East from a different angle – not one dominated by wars, ‘intellectuals’, ‘great men’ or high politics, but by late nights in cabarets, wild music, and women calling for change.

PART I

SETTINGTHE SCENE

CHAPTER I

‘Pardon Me, I’m Drunk’

IN THE CLASSIC EGYPTIAN PLAYTHE PHANTOM, the main characters are having dinner soon after a particularly harsh government crackdown on vice – brothels have been closed, the wine shops shuttered, and Cairo’s hashish supplies cast into the fires. One disappointed character consoles the assembled guests with an ‘Elegy to Satan’, in which he describes the city’s debauched nightlife in earlier days, a demi-monde of drunkards, musicians, hashish-heads, clowns and prostitutes. ‘From now on,’ his poem laments, ‘no more hugging, no more fucking, no more kissing’; the good times have come to an end.1

This scene is not from modern Egypt. It was written for shadow puppets in the thirteenth century CE by Ibn Daniyal, an eye doctor originally from Mosul but based in Cairo. He composed his poem under the administration of the Mamluk Sultan Baibars, who is best known for his military victories against the crusaders and the Mongols but also, according to Ibn Daniyal’s play, started a moral crusade of his own at home. One of his three extant shadow plays, The Phantom is among the earliest dramatic scripts in Arabic to survive from Egypt and a rare medieval example of the genre, in which a huge range of elegant and finely made leather puppets acted out bawdy and often unapologetically obscene dramas. Light on plot – but stuffed full of songs and short sketches – the plays seem designed to show off the poet’s wit and the puppeteer’s skill while painting a vivid picture of the city’s culture and entertainment. Another of Ibn Daniyal’s shadow plays, Strange and Amazing, consists of a procession of characters who enter briefly to perform short skits and then leave. He populated Mamluk Egypt with an array of oddballs, acrobats, preachers, magicians, animal tamers, tricksters, tattooists and sword swallowers.

For centuries afterwards, shadow plays continued to be performed on the streets of Egypt and at religious festivals. Later surviving manuscripts include The Crocodile, in which a fisherman is eaten by a crocodile as a Nubian and a North African compete to save him from its stomach, and The Café, in which two characters debate the relative merits of homosexuality and heterosexuality. The proponent of heterosexuality wins the argument but loses the war because the former proponent of homosexuality promptly has an affair with his wife. As late as 1911, the German Orientalist scholar (and later spy) Curt Prüfer described the shadow plays that he had seen:

The player sets up his kushk, a movable wooden booth, wherever he wishes it; there he sits behind a tightly stretched muslin curtain, which is lighted from behind by a primitive oil lamp, and presses the transparent leather figures against the curtain by means of wooden sticks fastened to figures at the back, and serving at the same time to move their limbs. The player is supported by his troupe, who help him in the manipulation of the figures and in reciting the different roles.2

At the beginning of the 1800s, some six hundred years after Ibn Daniyal’s plays were first performed, many different public entertainment traditions existed alongside shadow plays. There was, for instance, another kind of puppet show called Aragoz, an Egyptian version of the Turkish shadow plays called Karagoz, that used hand puppets like a Punch and Judy show but kept the stock characters, slapstick humour and dirty jokes characteristic of the shadow theatre. As well as puppet shows, itinerant farce players (usually called Muhabbazin) were a regular feature at weddings, religious ceremonies and private parties. Their sketches, often concerned with contemporary rulers or the plight of the downtrodden, managed to mock the strong and weak alike. ‘It is chiefly by vulgar jests, and indecent actions, that they amuse, and obtain applause,’ the traveller and Orientalist Edward Lane wrote in the 1830s. Performances like these were not based on a precise script and had considerable room for improvisation and audience interaction. For the most part, details about the shows come from the (not always reliable) accounts of European travellers.3

In the cafés, storytellers recited oral epics, sometimes with musical backing and sometimes without. The most popular tales in the early nineteenth century were al-Sira al-Hilaliyya, the epic story of the migration of the Beni Hilal tribe from the Arabian Peninsula to North Africa; Sirat Antar, a tale about Antar, the son of a slave who became a great poet and warrior in pre-Islamic Arabia; and al-Sira al-Zahiriyya, an epic about the life of the Sultan Baibars (whose reforms Ibn Daniyal had mocked centuries before).

Then there were the singers and dancers. According to Lane, still a major source for nineteenth-century entertainment history (even if used a little cautiously), Egyptians were, in comparison to the British, ‘excessively fond of music’. He divided musical entertainers into three main types. The first was the alatee, a male musician who sang and accompanied himself on an instrument such as the oud (lute). Lane viewed these as ‘people of very dissolute habits’; however, he remarked that they were ‘hired at most grand entertainments, to amuse the company; and on these occasions they are usually supplied with brandy, or other spirituous liquors, which they sometimes drink until they can no longer sing, nor strike a chord’. The second type was the almeh, a female singer who almost exclusively performed in the houses of the elite. Lane said these women were often very skilled, writing their own poetry and receiving large sums for their performances. The third kind of musical entertainer, in Lane’s early nineteenth-century categorisation, was the ghawazee, a dancing girl who performed either in public streets or at the private parties of ordinary people. He considered their dancing to be inelegant and more highly sexualised than the dances he had seen in wealthy houses, but he admitted that ‘women, as well as men, take delight in witnessing their performances’ even if ‘many persons among the higher classes, and the more religious, disapprove of them’.4

For the residents of Cairo at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the city had a rich cultural life. But the coming decades would transform Egypt – and its nightlife – almost beyond recognition. Over this time, Egypt would develop from a largely unremarkable province of the Ottoman Empire into a flourishing, politically important modern state; a booming economic powerhouse; and before long, a (semi-formal) protectorate of the British Empire. As a new Egypt took shape, theatres, cinemas, cabarets and music halls – like those that were popular around the world – would take over Cairo. By the end of the century, Cairo’s nightlife would converge on the district of Ezbekiyya, named after an old Mamluk emir called Ezbek who once had a palace there. The district boasted at least thirteen large entertainment venues and innumerable smaller bars and cafés. Many of these places offered shows by singers or dancers in rooms heavy with smoke and alcohol, and they also housed gambling halls, hashish dens and more. This was Cairo’s equivalent of Montmartre, Broadway or Soho.

Alongside the nightlife venues were several hotels that catered to European travellers. Most prominent among them was Shepheard’s, with its renowned terrace where, in the winter season, the world’s elite thronged. According to an article in Harper’s Bazaar in 1884, ‘In olden days, before the canal diverted the course of travel between India and Egypt, Shepheard’s Hotel was the spot where the streams from the East and West met.’5 These hotels, combined with the new French-style buildings springing up in this part of Cairo, led people to call Ezbekiyya the European Quarter. More was going on there, however, than that name indicates. To the north of the gardens was St. Mark’s Cathedral, seat of the Coptic Patriarchate and one of the most important sites of Egyptian Christianity. To the east was Mouski, a historic area with Arabic architecture and narrow streets leading to the heart of the Fatimid old city, which Europeans viewed as hugely exotic. Ezbekiyya, far from being just a tourists’ hotspot, was the place for pleasure-seeking Cairenes to go out at night.

*

The story of Ezbekiyya is also the story of modern Egypt. In most history books, the year 1798 is singled out as the beginning of a new phase in the country’s history. In that year, Napoleon led his armies across the Mediterranean and conquered Egypt, defeating the Ottoman armies at the Battle of the Pyramids. Living out a fantasy in which he played a cross between Muhammad and Alexander the Great, the French emperor took Cairo by storm, accompanied by thousands of soldiers and a team of 151 savants tasked with a minute analysis of the history, culture and geography of this ‘antique land’. The French army took up residence all around Cairo, including Ezbekiyya – then a neighbourhood of only middling importance – where they set up a temporary theatre to entertain the troops with dramatic performances including Voltaire’s Death of Caesar and a new opera (The Two Millers) written by two members of the expedition.

Many people have been tempted to see the French invasion as a decisive turning point in Egypt’s history and the beginning of modernity in the country – for this reason, many books on modern Egyptian history begin in 1798. However, in reality, Napoleon’s short but romanticised Middle Eastern campaign (which lasted only until 1801) probably had more of an impact on the European imagination than anything else. The most important result of the French invasion came about totally by chance. In 1801 Muhammad Ali, an Albanian military commander, arrived from Kavala in modern-day Greece as second-in-command of a small contingent of soldiers – one small part of the joint Ottoman–British army that defeated the French. But by 1805 Muhammad Ali had skilfully managed to manipulate the political chaos and make himself the Ottoman governor of Egypt. In 1811, he took complete control of the country by comprehensively defeating his powerful rivals – a caste of warrior-slaves called the Mamluks, who had been the Ottoman vassals in Egypt before the French invasion. In a brutal and now legendary ploy, he invited hundreds of the most powerful Mamluks to a party in Cairo’s citadel; once they were inside, he shut the gates and had them all killed.

From the 1810s to the 1840s, Muhammad Ali turned Egypt into a de facto self-governing state, establishing a dynasty of his own only nominally under the control of the Ottoman Empire. He instigated a huge programme of modernisation, professionalising the army, bringing in European advisors to help with state-building projects, and setting up a printing press, hospitals and educational institutes. He also set about the work of transforming Ezbekiyya into something new. In the early days of his reign, the area had been an elite enclave consisting of sumptuous palaces built around a small lake. The lake was drained and then turned into a garden, and soon hotels, small ramshackle bars, billiard rooms and music halls all started popping up around it.

By the time Muhammad Ali died in 1849, he had established a dynasty that his sons and grandsons continued with varying degrees of success for almost 150 years. After a brief period of rule by Muhammad Ali’s sons Ibrahim and Said and his grandson Abbas, ‘Ismail the Magnificent’, another grandson of Muhammad Ali, became the khedive (viceroy) of Egypt in 1863 (though the Ottomans did not let him formally use the title until 1867). More than anyone else, Ismail turned Ezbekiyya (and downtown Cairo more generally) into the centre of Egypt’s cultural life. In the 1860s, because of the American Civil War, cotton was in high demand globally, and Egypt capitalised on this. The crop, which had only recently been introduced to the country by Muhammad Ali, became a gold mine, and Ismail suddenly found he had huge amounts of money to spend on his passion for building. He spent lavishly on public works and private extravagances across the country, including the Gezira Palace that now houses the Marriott Hotel in Zamalek.

Ismail also began to design a whole new centre for Cairo. His workers knocked down crumbling old palaces to build new streets. He employed Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps, the former chief gardener of Paris who had planned the Bois de Boulogne, to lay out the new Ezbekiyya Gardens on the spot where Muhammad Ali had drained the old lake. Around the new gardens, Ismail ordered the construction of a series of luxury entertainment venues. Between 1869 and 1872, a ‘French theatre’, a circus, a hippodrome, a ‘garden theatre’ and an Italian-style opera house all sprang up. As pride of place in his building project, he erected a large bronze equestrian statue of his own illustrious father, the successful General Ibrahim Pasha, by the French sculptor Charles Cordier. Ibrahim Pasha’s statue pointed its finger to the horizon in a triumphal pose, befitting a general who had won decisive victories for his father, Muhammad Ali, in the Arabian Peninsula, Greece and Syria.

Opera Square, Ezbekiyya, 1934.

In Ismail’s Ezbekiyya, modern Egyptian nightlife and entertainment were born and went on to thrive. Clowns, acrobats, farce players and animal trainers carried on as they had done for centuries – a shadow theatre existed in Ezbekiyya until 1909, when authorities shut it down because they considered it too raunchy – but new attractions were now on the rise too.

*

The Khedive Ismail’s vision for Cairo’s new entertainment district was dominated by theatre and opera, largely following European models in European languages. He wanted to show his court and his most elite subjects the best examples of those genres that existed, in order to glorify his rule. With the vast sums of money available to him as the ruler of Egypt, this goal was within his reach. In 1869, he inaugurated the Théâtre Français with a production of his favourite opera, Offenbach’s La belle Hélène. Two years later, Ismail realised one of his great triumphs when he persuaded the highly sought-after Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi, helped along by the vast sum of 150,000 gold francs, to write him an opera to be performed at his new opera house. The opera was Aida, the story of an Ethiopian princess in Pharaonic Egypt, and it premiered in Cairo in 1871. A long-standing myth holds that the opera was commissioned to celebrate the inauguration of the Suez Canal but was delayed. This is not, strictly speaking, true; but Ismail did use Aida in the same way that he used such large public works as the Suez Canal: to project an image of a powerful global leader.

Although not commissioned directly by Ismail, an Arabic-speaking dramatic movement soon emerged in Ezbekiyya to follow these European classics. The colourful and eccentric figure Yaqub Sanua, who went by the name of James, is now usually considered to be the father of Arabic theatre in Egypt. He was the son of an Egyptian Jewish mother and a Sephardic Jewish father from the Tuscan port of Livorno who worked as an advisor to a minor member of the khedivial family in Cairo. Over the next seventy years the Jewish population of Egypt would increase many-fold, but in the mid-nineteenth century it was not huge. In Cairo, as the London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews estimated in 1856, there were around 4,000 Jews in a population of about 300,000. A number of prominent Sephardic families had some power and influence, but most of the Jewish population led ordinary lives, though not free from discrimination or prejudice.

James himself was a dreamer, a visionary and a prolific self-publicist. He was also a committed Egyptian nationalist and an enthusiastic promoter of Arabic-language culture. As a teenager he was sent to study in Livorno on a government scholarship. On his return he worked for a while as a tutor to the children of the khedivial court before landing an appointment in 1868 at the École Polytechnique, an institute in Cairo for the study of engineering and architecture. While enjoying this comfortable bourgeois existence in the summer of 1870, James saw two touring theatrical companies – one French, one Italian – performing at Ismail’s new open-air theatre in Ezbekiyya Gardens. He might have seen drama of this kind in Livorno, but he had almost certainly never been to a play in Cairo before. He approached the companies and asked if he could help with their production. They both welcomed assistance from this enterprising young Egyptian and invited him to join the troupes temporarily (it is unclear whether he acted with them or helped in some other way). In his later recollections, James identified this as the precise moment that his passion for theatre was sparked.

Once these touring troupes had left Cairo, James quickly got to work forming a theatrical company that would put on his own plays in Arabic. He gathered and trained a group of actors, wrote a script, and was ready for his opening night by the next summer. In a speech in Paris more than thirty years later, James could still remember the moment. He described, perhaps with a degree of poetic licence, the vast audience of 3,000 people gathered around the stage – men and women of all colours, including some government ministers and European ambassadors. ‘A thunder of applause welcomed us and cries of bravo in all the languages of the Tower of Babel,’ James reminisced proudly. Backstage, the actors had been buoyed by the gift of a bottle of three-star Cognac from a wealthy Egyptian fan and, when they came onstage, delivered an assured performance of the newly written script.6

That day the troupe performed a short one-act farce known sometimes as The Harem and sometimes as The Bowman. Usually considered the first piece of modern Egyptian drama, this short comedy mocked both the increasingly outdated, elite Egyptian system of the harem, in which the wives and concubines of the wealthy lived together in a separate area of the house, as well as the obsession that foreign visitors had with these harems (and myths that had grown around them). The story begins with a visiting European prince who is desperate to have an authentic illicit experience in a genuine Arab harem. He makes a bet of 1,000 Egyptian pounds with the son of a well-connected young Egyptian noble. Within a month, the prince says, he will be able smuggle himself inside the women’s quarters of some local pasha (an Ottoman noble title whose closest equivalent in English may be ‘lord’).

Just a few days later, the prince receives good news. A letter arrives for him from a woman who (she says) has seen him from the harem as he was visiting her house, and his blue eyes have pierced her heart. The letter tells him to wait that night at the foot of the Sphinx, where a eunuch will pick him up and take him to her. After nightfall he goes to the agreed spot – and, sure enough, the eunuch soon appears. The prince is blindfolded and driven in secret to the palace, where he is smuggled into the women’s rooms.

Now that they have the European prince at their mercy, the women of the harem play a cruel trick on him. They dress an attractive sixteen-year-old Syrian boy in women’s clothes and pretend that he is the pasha’s favourite out of all of them. They lead the prince into a secluded spot where he removes his blindfold. Seeing the boy in front of him, he is captivated and attempts to woo what he thinks is the young girl. He declares his love, and ‘she’ reciprocates. As the two lovers are on the verge of a passionate embrace, the old, bearded pasha bursts into the room, interrupting their tryst.

Scandalised by the breach of his inner sanctum, he threatens to punish both of the transgressors by putting them in a sack and feeding them to the crocodiles. The holidaying prince pleads for mercy, even offering to give the pasha all of the 1,000 Egyptian pounds that he stands to win in his bet. At this point the characters remove their different disguises. The pasha takes off his white beard to reveal himself as the young man who had taken the prince’s wager at the beginning of the play. The boy takes off his women’s clothing to reveal himself as a young military officer, no doubt the bowman that the play is named after. Then a group of the prince’s friends all emerge, laughing, from the next room, and the play ends with a sumptuous dinner in the palace gardens.

Over the next two years, James’s company went on to produce thirty-two different plays. His repertoire mostly consisted of one-act farces or comedies of manners, similar to the first play he had written, with evocative names like The Dandy of Cairo, The Alexandrian Princess or The Tourist and the Donkey Boy. Characters in the plays were drawn from the many different communities that lived in Egypt at the time – Nubian, Armenian, French, Greek, Arab and English. There were frequent appearances from comic stock characters, among whom were the hashish-addled servant, the foreigner out of his or her depth, and the upper-crust Egyptian who tries, with comic incompetence, to ape European culture. This kind of thing later became the bread-and-butter of Egyptian comedy for many decades, and James’s dramatic style may well have owed an unacknowledged debt to the shadow plays or travelling farce players of nineteenth-century Cairo.

Ultimately, James’s theatrical career did not last long; by the end of 1872, his troupe had stopped performing. The Khedive Ismail was originally very supportive of the company – he was not against Arabic theatre, as long as it served his aims. But James later said that he fell out of favour with Ismail, who forced him to end his theatrical activities and eventually get out of Egypt; James suspected that his rivals, some ‘gros bonnets’ and ‘sworn enemies of progress and civilisation’ were whispering poisonous words to Egypt’s ruler, trying to persuade him that James was hiding anti-government messages in his plays. An 1879 article in the Saturday Review claimed that ‘the wrongs of the Fellah [‘peasant’] and the corruption of Ismail’s government were treated by him in terms that quickly brought upon him the displeasure of the authorities’. James himself later circulated the story that his play The Two Wives, which criticised the practice of taking more than one wife, offended Ismail, who had several wives. The khedive’s riposte to James was, ‘If you don’t have stout enough kidneys to please more than one woman, that’s no reason to put others off.’7

James may also have had more prosaic reasons for drifting away from the theatre in the 1870s. The money was running out. The cotton boom of the 1860s was starting to wane. And Ismail’s extravagance was starting to catch up with him. He had borrowed heavily from European creditors and – alongside his disastrous decision to wage a war in Ethiopia – his spending was unsustainable. Finally, in 1876, a debt-ridden Egypt went bankrupt and, after long negotiations, British and French experts were brought into a new ministry created to supervise the country’s finances on behalf of foreign lenders.

Politically, the late 1870s were extremely charged. Britain, in particular, began to exert more influence in Egypt; as this happened, James Sanua turned his attention towards more conventional politics, becoming a vocal critic of the khedive’s compliance with further European expansion and playing a minor part in big political changes to come. In 1878 he started a fiercely anti-colonial and anti-Ismail satirical magazine called Abou Naddara Zarqa (The man with the blue glasses), whose circulation soon reached 50,000 copies in a population of around 6 million. Before the year was over, the magazine was bringing James unwanted kinds of attention and, after enduring two assassination attempts, he decided to leave Egypt for self-imposed exile in Paris. There he found a new permanent home for his journal, now simply called Abou Naddara (omitting the adjective zarqa, ‘blue’), in Paris’s Rue du Caire. Under this new name, and with the protection of exile, he began to publish more savage attacks on both the British and Egyptian ruling elite.

The European powers, however, did not stop their meddling in Egypt. Despite the agreements they had come to a few years before, in 1879 they decided to remove the Khedive Ismail from Egypt’s throne and appoint his son Tawfiq as khedive in his place. But this did not stop the turmoil; in 1881 an Egyptian army officer called Ahmed Urabi led a revolt based on a new constitution, which he had drafted, and calling for parliamentary government. James Sanua’s satirical journal got behind this new movement from Paris, filling the magazine with flattering cartoons of the Egyptian rebel. The British were so worried about the possibility that Urabi could take control of Egypt that they launched a military invasion to quash his uprising, which they painted as fanatical and dangerous. In 1882, claiming to be worried on behalf of foreign creditors and the European population of Egypt, the British installed Evelyn Baring (Lord Cromer) as their new consul general. Although the Khedive Tawfiq was kept on the throne and Egypt officially remained in the Ottoman Empire, Cromer and the British were now in effective control of the country.

James Sanua continued publishing magazines in Paris until the 1910s. He also became something of a celebrity in France, performing comic monologues at conferences and walking around with medals on his chest of fourteen grand orders of chivalry – which he claimed he had been awarded by governments across the world, including those of Persia, Tunisia and the important Indian Ocean trading stations of Obock, Zanzibar and Grande Comore. In these later years he wrote an autobiographical play, which he extravagantly named The Sufferings of Egypt’s Molière. This dramatised account of his theatrical experiment of the early 1870s was published in Paris in the early twentieth century. In 1912 James died in Paris and now lies buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery.

*

After the lull of theatrical activities in the 1870s and then the political turmoil of 1882, Arabic drama seemed to be on a downward trajectory in Egypt (after the British invasion of 1882 there is no record of any dramatic productions in Arabic until 1884). The theatre scene was only saved by a wave of theatrical companies coming in from the Levant (al-Sham in Arabic, an area that encompasses what is today Syria, Lebanon and Israel-Palestine). Arabic drama had existed there since at least 1848, when a troupe in Beirut had performed a play inspired by Molière’s L’Avare, and in the 1880s several thriving companies were plying their trade to the East of the Mediterranean.

By the mid-1880s, Cairo was again looking like an attractive place to visit – politically and economically stable, at least for the moment – and at the same time, poverty, hunger and sometimes repressive Ottoman policies were pushing people away from the Levant. Refugees from the area were starting to travel across the world, some of them ending up as far away as the Americas, but many came to Egypt, where the theatrically minded flocked to Ezbekiyya and started giving their own performances to Egyptian audiences hungry for Arabic plays. Ismail’s ambitious theatre schemes were faltering; two decades after the khedive had begun four grand projects in Ezbekiyya – the opera house, the French theatre, the circus and the hippodrome – only one, the opera house, remained. But these experienced Arabic-speaking actors, who had already been performing in Beirut and Damascus, started a new revolution in Arabic-language theatre in Cairo.

The Levantine troupes soon found enthusiastic support from Egyptians. One ‘group of patriots’ clubbed together to build a theatre for the Levantine director Sulayman al-Qardahi; it was located to the north of Ezbekiyya Gardens, close to the Grand Bar. Two of these recent immigrants from across the Mediterranean moved into theatres across the road from one another, in a square near the opera house called Ataba al-Khadra. One of the theatres burned down in 1900, but the other continued to prosper for years.

These theatrical troupes had eclectic repertoires. They often performed their own Arabic versions of the classics of European drama – works by Racine, Corneille and Shakespeare were among the most popular. There was good money to be made as a translator, and a cottage industry of multilingual writers formed which could meet the demand for new scripts. They often lightly adapted plays for local tastes, sometimes changing names and places, sometimes changing the plot itself, and always adding songs and musical interludes to the action (when one company tried to perform a version of Hamlet without singing, the audience complained so much that the troupe never repeated the experiment). The titles gave clues about what audience members should expect, since many of them would have been unfamiliar with the originals. So, Romeo and Juliet became ‘The Martyrs of Passion’, Othello was given the title ‘The Moroccan Commander’ or ‘The Schemes of Women’, and Corneille’s Le Cid was known as ‘Passion and Revenge’.

But the troupes did not only rework European classics. In these early days, Arabic theatre took influences from anywhere it could find them. Some performances were based on stories taken from Islamic history and vignettes from the Arabian Nights. Legends about the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid were particularly popular sources for plays, as was the life of the pre-Islamic hero Antar ibn Shaddad, whose epic was still being sung by storytellers in Cairo’s cafés.

Dancers at the Old Eldorado music hall.

Before long, some Egyptian writers also began to write their own plays and stage them. This group included one young lawyer, Ismail Asim, who gave up his lucrative profession to join the new dramatic movement. His most famous play was called Brotherly Truth and focused on the story of a young libertine called Nadim. He has been squandering his life in the bars and gambling dens of Ezbekiyya, but he is eventually redeemed after his father dies – he gives up his dissolute existence, becoming a successful merchant and ensuring the family’s survival.

At first, the expanding world of the theatre was overwhelmingly male. In these early days, female roles in plays were often taken by boys, because women could not be found to play them. As is so often the case, actress in Egypt was coming to be seen as a byword for immorality, even prostitution, and was not considered a respectable profession for women. Most of the women who broke this taboo came from the Levant. When Sulayman al-Qardahi’s Syrian troupe first arrived in Egypt in the 1880s, his wife, Christine, appeared onstage, as did at least one other actress, known as ‘Leila the Jewess’.8 Muslim women did not usually act onstage in this early period, a phenomenon often noted but seldom explained. It may have been because Muslims at the time had stricter views about the appearance of women in public than did Jews and Christians. Or the concerns may have been more general ones of maintaining propriety; minority religions, already outside the mainstream, might have been less worried by such niceties than were Muslims, who made up around 90 per cent of the population.

Audiences at the time would also have been predominantly male. Women were certainly present at the performances of most plays, but they were in the minority and usually segregated. Ismail’s opera house had separate boxes, concealed by a kind of latticework that female patrons could look out of without being seen. We cannot be certain that every single theatre was like this – elite Egyptians in the late nineteenth century placed much more emphasis on female ‘seclusion’ than other classes did – but it is likely that comparable sex segregation was practised in most theatres in the late nineteenth century.

It is perhaps surprising, therefore, that probably the most indepth autobiographical account of a member of one of these Levantine theatre troupes in Egypt was written by a woman. In an article published in 1915 in al-Ahram newspaper, one of the biggest female stars of early Egyptian theatre, Mariam Sumat, was given the chance to tell the story of her career. ‘I have stood on Arabic stages and acted different historical scenes to the generous Egyptian public for twenty-five years and I have won the respect of troupe leaders and actors,’ she said. Finally, after all that time, she was going to tell her readers about ‘the stages that acting went through, from its foundation to where it is now, and the changes that happened to it along the way’.9

Like many others, Mariam had a family connection to the stage. Her father had been a merchant in Syria, trading in jewels and precious stones. Then one day in the late 1880s, for reasons she does not fully explain, he decided to pack it all in and try his luck as an actor in Egypt. His first real break occurred after he became friendly with the Levantine troupe leader Iskandar Farah, who started to give him roles in his plays. It was also this friendship that gave Mariam her own path to the stage. Once, when Iskandar was visiting the family house, he encouraged her father to let Mariam start acting. He talked at great length about the lofty glories that actresses around the world had attained. Apparently persuaded by the speech, Mariam’s father allowed her to join the profession and she soon made her acting debut in a small troupe called the Society of Learning. Her first play was an Arabic adaptation of Jean Racine’s Mithridate, a tragedy about the ancient King of Pontus, one of the great enemies of Rome in the first century BCE. Mariam played Monime, Mithridate’s fiancée, who ends the play pledging to take vengeance for Mithridate’s death with his son Xiphares, her new lover.

As the theatre boom of the late nineteenth century continued, more troupes sprang into life. Mariam was part of a generation of young actresses that included Labiba Manoli and her sister Mariam, Milia Dayan, and the Estati sisters, Ibriz and Almaz, whose names translate as ‘gold’ and ‘diamond’ respectively. They moved back and forth between troupes, competing for good roles. Unfortunately, because of scant information about the lives of these women and only short notices in newspapers to identify them, they remain largely a parade of names on the edges of the historical record.

The life of a jobbing actress in this period, judging from Mariam’s memoirs, was almost impossibly complicated. She herself changed troupes frequently and, as well as recounting successes in Cairo, she recalled her tours in the countryside of Egypt and even as far as Damascus and Beirut. Theatrical companies had to do what they could to stand out. In addition to the play itself, theatrical notices at the time also advertised short comic skits and ‘pantomimes’, as well as lots of singing and dancing. Singing was such a crucial part of what people expected from live entertainment that troupes would have to add their own songs to the action of the plays that had no singing parts. On Cairo’s stages, every play became a musical and every actor a singer. As the 1890s continued, more and more ploys were invented to boost ticket sales. Some companies advertised that there would be a raffle before the performance. With the advent of new technology such as the cinematograph, short films also became part of the night’s attractions.

Problems of funding and power struggles at the top of troupes followed wherever Mariam went, as did arguments and jealousy between the ordinary members. All this left Mariam upset with the pettiness of her fellow actors and actresses. In her view, the early days of Egyptian theatre would have produced much better work if not for the envy, jealousy and ambition of others. ‘Oh greed!’ she lamented, ‘corrupter of success, sure path to ruin, and destroyer of noble work.’10