Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

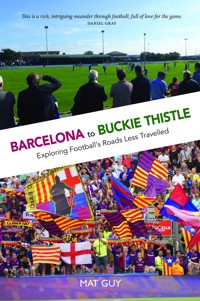

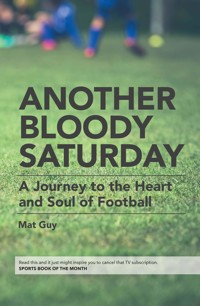

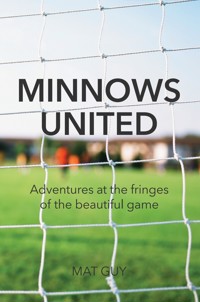

Following his first book, Another Bloody Saturday: A Journey to the Heart and Soul of Football, Mat Guy continues his exploration of the 'beautiful game' in Minnows United; an ode to the unsung heroes of football matches taking place out of the limelight, all over the world. From little known teams within the UK, to teams representing countries that, to most of the world, don't even exist, Mat Guy travels to remote parts of the globe to experience football not only on the fringes of the pitch, but on the fringes of the world. On his travels, he watches matches in Iceland, interviews members of the Tibetan Women's Football team, explores the impact of football in war-torn Palestine and explores the unsung heroes in the football clubs present throughout the length of the UK. What he finds is countries transcending the game itself and instead building communities, lifelines and friendship with football at the centre.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 478

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MAT GUY lives in Southampton with his wife Deb and cat Ellie. He has written about football for a number of magazines, including Box to Box, The Goalden Times, Thin White Line, and Late Tackle. Minnows United is his second book. Another Bloody Saturday: A Journey to the Heart and Soul of Football was published by Luath Press in October 2015.

First published 2017

ISBN: 978-1-912147-06-9

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by Ashford Colour Press, Gosport

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

Photographs (except where indicated) and text © Mat Guy 2017

This book is dedicated to my grandfather, who showed me that life can be joyous – as long as you remain faithful to your hopes and dreams.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 European Dreaming: F91 Dudelange

CHAPTER 2 If Football Shirts Could Talk: Palestine

CHAPTER 3 The End of the Classifieds and Beyond: Llanelli Town

CHAPTER 4 Neither Here nor There: Berwick Rangers

CHAPTER 5 Cyril Smith and the Unofficial Footballers

CHAPTER 6 The Forbidden Team from a Forbidden County: Tibetan Women’s Football

CHAPTER 7 A Club on the Edge: Port Talbot Town

CHAPTER 8 The Club That Wouldn’t Die: Accrington Stanley

CHAPTER 9 At the Edge of the World: UMF Víkingur Olafsvik, Iceland

CHAPTER 10 Adriano Moke

CHAPTER 11 Sarah Wiltshire and the Women’s Super League

CHAPTER 12 Displaced, Refugee, Unrecognised: Three National Teams in Search of a Nation

CHAPTER 13 Southampton A and B: Discovering Football’s Forgotten Teams

CHAPTER 14 Life in the Shadows: Macclesfield Town

CHAPTER 15 Full Circle: More European Dreaming

Acknowledgements

I WILL BE forever grateful to Alice Latchford, this book’s editor, for all her hard work, insight, and suggestions. So too Gavin MacDougall and Luath Press for their faith in the people and stories within these pages.

Indeed, without the stories this book would be nothing. I owe a debt of thanks to those who shared their experiences with me: Jamal Zaqout, Motaz Albuhaisi, and Moahmoud Sarsak from Gaza, Cassie Childers, Sonam Dolma, Sonam Sangmo, and Tenzin Dekyong from Tibet Women’s Soccer, Keil Clitheroe, Adam and Julie Houlden, Nick Westwell, Adam Scarborough from Accrington Stanley, Dan Hatfield from Selfoss, Anton Jonas Illugason from Olafsvik, Sarah Wiltshire from Yeovil Town Ladies, Iggy from Darfur United, Mick Ellard from Southampton and Rob Heys from Macclesfield Town – thank you, from the bottom of my heart for opening up a wonderful world to me.

Introduction

A LIFE AT the fringes of football, far from the media spotlight afforded the world’s biggest leagues and the most successful national teams, can be a largely anonymous one.

Supporters, players, clubs, and nations that find themselves existing right at the very edge of the game, be it geographically, politically, through size and status, historically or ideologically, do so in a vacuum devoid of attention, money, and quite possibly to those from above looking down, purpose.

However, among the clubs and nations that physically cling to the very ends of the footballing earth; are national teams that exist in a twilight world beyond the international scene, thanks to political decisions taken far from any football pitch. Among the teams and their supporters constantly living in the shadow of the games giants, in lowly leagues populated by ageing ramshackle stadiums and dwindling attendances, there exist stories, living histories that better detail all that is captivating and magical about this simple game than that which is offered through satellite television’s focus on the biggest and the best.

In a game fast becoming dominated by money, it is those furthest from it that tell the story of football in its purest form, and that can help to re-connect a soul to their first memories of going to their first ever match, or the moment that kicking a ball about a scrap of land or backyard became an obsession. Among the stories of players, clubs, and supporters rarely written about exists the heartbeat and foundation blocks that enables the Premier League and Champions League to be the enormous entities that they are.

Without these fundamental passions and truths that exist, have always existed at the very fringes of mainstream football, at its grassroots, everything that has gone beyond it could not.

It seems apt in a time where the higher echelons of the sport are beginning to lose this understanding of the importance of the game further down the food chain that we begin to explore it more, cherish it. Because in a world where FA Cup replays are being mooted for the scrapheap, and initial matches to be played in midweek to avoid fixture congestion for the bigger teams; where qualification for the World Cup and European Championships could soon be preceded by a pre-qualifying tournament between Europe’s ‘lesser’ nations, so as the ‘larger’ ones don’t have so many ‘unnecessary’ and ‘meaningless’ internationals – the world of the minnow needs to be trumpeted like never before.

The riches of the Champions League, and the Premier League seem to be blinding governing bodies to the simple realities that football is such a universal sport because of its inclusivity.

Every young child with a ball can dream of one day playing for their team, their country, of playing in the FA Cup or the World Cup. And if they can’t play in the final, then maybe one of the stages preceding it.

As a young boy, the qualifying rounds of the FA Cup felt just as exciting as sitting down to watch the final on television the following May. Salisbury FC’s old and ramshackle (even back in the ’80s when I was a young boy) and sadly long gone Victoria Park had an extra touch of magic about it on FA Cup qualifying round day.

Sitting down with my grandfather in Victoria Park’s only and very basic stand (Grandad had made two cushions out of foam to protect us from the cold concrete seating) the anticipation of a good win, followed by a couple more, that could result in little old Salisbury drawing a football league team in the first round proper had both the supporters in the stand, and the part-time players crammed into their changing room beneath an old, creaking pavilion, dreaming of something special on a blustery autumn afternoon as far from the early summer sun of Cup final day as you could get.

By threatening to devalue the competition by switching it to mid-week, by scrapping replays that could see a minnow team pull off an amazing feat by drawing at home to more illustrious league opposition – setting up a dream return match at a stadium players and fans alike could only dream of – the magic of the competition would be eroded, diluted.

And with it the inclusivity; that any child that dreamt and persevered hard enough could find themselves on a Saturday afternoon running out against Manchester United in the FA Cup third round. That any part-time player could maybe have the chance to do this any given season is what has preserved the competition as the most loved and revered competition on the planet.

It will be, as always, the teams far from the big leagues that suffer the most from these proposed changes and who will lose the slightest of opportunities to mix it with the big time, for just one day.

So too the minnows of the international game will suffer if they are never allowed to test themselves, to develop, by playing against the World’s best.

It is what makes the game so special, that the Faroe Islands, Luxembourg, Gibraltar can be drawn to play against Germany and Spain in a qualifying group; that school teachers and firemen and bank clerks can have the opportunity to take on the champions of the world.

It is the connectivity between all abilities that makes football the most watched and loved sport on the planet; it is for anyone, everyone, who can aspire to live out their dreams, no matter from what lowly starting point they find themselves.

It is this seemingly terminal fracturing between the big time and the rest that compelled me to explore and celebrate football that exists way out on the fringes of the game; to check the heartbeat of the sports very essence.

It is, after all, a game that is bigger than the global football entities that run it, that reaches out to more people on a daily basis than any satellite television audience, that enables and gives expression to those that FIFA and the United Nations don’t.

Beyond the glamour and money of the elite levels of football there are three things that preserve the game, no matter how remote, forgotten, or forsaken it may find itself: identity, belonging, and meaning.

These three fundamentals have helped keep small teams with no money afloat for more than 100 years and counting. They have helped preserve the histories and stories of the people that once populated them through fading pictures on clubhouse walls, scrapbooks, dusty trophy cabinets, and the passing down of tales from grandparent to grandchild. Without it I would have never learned of the amazing story of Cyril Smith, the kindly old man on the gate at Salisbury selling programmes, whose self-depreciation hid a remarkable past. Thankfully his friendship with my grandfather helped offer up enough of his tale for me to discover after his passing.

Identity, belonging and meaning have enabled communities almost lost to the world to maintain a presence through their love of football. Nations and groups failed by official world bodies survive in an unofficial capacity out on the pitch; shining a light on the reasons for their isolation, as well as celebrating a culture that others would rather have us forget, and a game that they will not be denied.

The fringes of the sport are populated with the obscure, the forgotten, the ignored, the persecuted, and sometimes the taboo that football in the mainstream struggles to deal with.

It is a world of humour, passion, beauty, and wonder. It can also be a world pain, horror, and suffering.

But throughout it all, football way out on the edges of mainstream consciousness maintains a rich vibrancy, a vitality, and a deep-rooted necessity that seems to be able to deal with the ever-greater isolation it finds itself existing in.

Having spent more than a year exploring just a handful of the countless fascinating clubs, players, and nations out there, you can’t help but wonder two things: just how many more amazing stories are there out there waiting to be discovered, and exactly who is the poorer for drifting away from the other – those on the fringes, or those that seem to be pulling away from the very spirit of the game?

The following 15 stories from football’s forgotten teams; of players and teams mostly ignored by the mainstream media, of people forsaken by politics and humanity, of clubs and nations isolated due to geography helps to reveal a world of diversity, colour, passion, and dedication.

Regardless of size, location, status, the sense of belonging and meaning that every player and supporter in the book takes from their team is every bit as vital and important as that of any fan in the Premier League. In some cases, more so.

Identity, meaning, a sense of self and of belonging cannot be quantified through FIFA rankings, or league tables. And these things don’t even begin to consider all those that lay beyond them, containing as they do only nations recognised by the UN and FIFA. Those at the very foot of the football pyramid and on the fringes of the mainstream derive as much meaning from the game as anyone else.

These tales follow European minnows, players surviving in war torn Palestine, clubs at the foot, and sometimes beyond the football classified results service on a Saturday afternoon. Clubs and players whose dedication makes them greater than the sum of their parts, forbidden national teams defying traditional boundaries and refugee teams clinging on to their very survival, they all offer an amazing insight into a vibrant world of footballing humanity that is often overlooked.

After having been on this journey that you are about to read, having witnessed the dedication and passion needed to circumvent a lack of finances, resources, and everything else, you could certainly argue that the real spirit of football truly is alive and well, but not necessarily where you would expect to find it.

CHAPTER 1

European Dreaming – F91 Dudelange

LUXEMBOURG, THERE HAS always been something about Luxembourg; a tiny country hidden, both politically, culturally, as well as on the sporting front, between much larger and grander European nations. But despite its size, or, in fact, because of it, there has been that special something that has made Luxembourg stand out where other countries don’t; something first initiated by a football programme between England and the world’s last surviving Grand Duchy arriving in the post when I was a ten-year-old boy.

My Grandfather, knowing that I loved football programmes almost as much as I loved football itself, had put the word out at the factory he worked in, asking his friends to pick up an extra one for his grandson if they ever happened to be at a match, which is why a week before Christmas in 1982 I found myself pouring over a programme between England and Luxembourg from a European Championship qualifier at Wembley Stadium.

Just like the Panini sticker album from the World Cup of that summer of ’82, in which I invested so many hours studying the information on teams from far-away lands, many of whom I had never even heard of before, I would spend an age reading and re-reading that programme. Marvelling at the strange sounding names of the teams that the Luxembourg squad played for back at home, peering into the team photo taken, to the eyes of an excitable ten year old in some exotic stadium, though in reality, and in the best case scenario upon looking at that same picture more than 30 years later, a dank, rain sodden and unfamiliar municipal stadium somewhere in Europe, more than likely long since lost to time and decay.

But to a young boy living in an age before the internet, where the world of football stretched as far as the coverage it received in The Daily Telegraph, my parents paper of choice, this programme opened up another world: a world of football beyond a young boy’s understanding; beyond the English First Division and the world football powers of Brazil and Italy, West Germany, as they were then, and all the rest that had played at the World Cup in Spain that summer.

This programme opened up a bigger, or rather smaller world of football outside that inner circle of the world’s ‘elite’, and it was fascinating, intoxicating, exciting, and seemed just as important and necessary, just as vital as that of Zico, Socrates, Tardelli, Rossi, and all the stars of that summer.

Just as I studied the information on the world’s best in my sticker album, so too did I the player profiles of that Luxembourg team, dreaming of what the club badges, the stadiums, the team shirts of Red Boys Differdange, Progres Niedercorn, Stade Dudelange, and the other club sides that they played for looked like.

That wonderment captured the imagination just as much as the unbelievable skills of that Brazil ’82 side, and for every hour spent staring at the erratically stuck in images of the World’s best in my sticker album, wondering about Zico’s Flamengo, and Socrates’ Corinthians, I spent longer devouring the exotic names and club sides of players playing for countries that I, or anyone else that I knew for that matter, knew nothing about.

To a young boy, the teams from El Salvador, Honduras, Peru, Cameroon, just like that team from Luxembourg, symbolised the unknown, adventure, and all the possibilities that flicking through a box of National Geographic maps from the ’40s and ’50s that my grandfather had kept, offered. Laying these maps out on my grandparents’ floor, I couldn’t help but wonder at the strange names of strange, far flung places. So, too, that old sticker book.

Joaquin Alonso Ventura played for Santiagueno in his native El Salvador. What did Santiagueno look like? What did the club’s stadium look like? The same questions arose for Mauricio Quintanilla, the El Salvadorian striker who played for Xelaju in Guatemala, and Jasem Yaqoub of Al-Qadesseyah, Kuwait, and Ernest Lottin Ebongue of Tonnerre Yaounde, Cameroon.

It seemed that, along with the standard fare of young children idolising the best players in the world, I found myself inextricably drawn to those unknown, ‘small-time’ forgotten players and teams as well, no matter where in the world. To me they did, and still do, matter as much as the greats of the game; their stories just as valid, as important as those of their more illustrious counterparts, maybe even more so for the tales they may have to tell.1

You can rank teams and nations according to their standard, but you can’t rank their importance, the pride of identity, of belonging, to fan and player alike, which remains just as significant and vital at the foot of the FIFA World rankings as it is at the top.

That sticker album and programme helped to open up a rich world of the minnow, the outsider that seemed to strike a chord in me: a shy boy that kept to himself, finding a world of football far from the bright lights and glare of the press, a world populated by the unknown footballer, the unknown fan very appealing. And it was no matter that no one outside of their country had ever heard of them; the players of these teams were competing at the World Cup, or in Luxembourg’s case, in a qualifying group for such a big tournament.

That deserved, in my mind, complete awe, irrespective that El Salvador lost ten one to Hungary and came bottom of their group; Ramirez Zapata, who didn’t make the cut for selection in the sticker album, and who therefore remains the faceless scorer of that consolation goal, their only one of the entire competition.

But the way they sung their national anthem, played with a passion as if their lives depended on it, even in the face of heavy defeat, only added to their mystique, and made me realise that regardless of their obscurity, their endeavour mattered, they mattered; and it made me wonder at their sporting lives away from the World Cup, and what that might look like.

It seemed obvious in a way, my love of this hidden, forgotten footballing world, full of possibility and adventure. After all, I had been guided in that direction by my grandfather, first through publications like National Geographic, then through the game I loved. It was that Luxembourg programme from Grandad, along with trips to see his team, Salisbury, play in the non-league ‘wilderness’ of the Southern League, as well as that barely three quarters full ’82 sticker album, that ignited my love for the underdog. And if ever there was an underdog, in European football at least, then it was Luxembourg.

The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg totals 998 square miles, making it one of the smallest sovereign nations in Europe. Indeed, it is ranked 179 in size out of the 194 independent countries in the world, and nestles between the borders of France, Belgium, and Germany, far from the main tourist routes through Western Europe. It is the world’s last remaining Grand Duchy; an historical anomaly, and a reminder of a bygone era of the Kings, Queens, Dukes and Duchesses that used to rule across Europe before war and revolution changed the political and cultural landscape forever.

After the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the lands that comprise modern day Luxembourg were disputed over between Prussia and the Netherlands. The Congress of Vienna formed Luxembourg as a Grand Duchy, hovering between the two states that would have equal influence over it, in an attempt to appease both.

In 1839 it became fully independent, and began a relatively anonymous life among its more illustrious and noisy neighbours, with a succession of Grand Dukes as head of state (the latest being Henri).

During World War Two it was, like nearly all of mainland Europe, invaded and annexed by the Third Reich. The government in exile based themselves in London and sent volunteers back to the mainland who participated in the Normandy Landings that helped defeat Hitler.

Given its history and close proximity, culturally as well as geographically, to its neighbours, it is no real surprise that there are three languages used in Luxembourg: French, German, and Luxembourgish, the latter being used by most in general conversation but not until quite recently in the written form.

Luxembourgish is a hybrid language and is classified as High German, though with over 5,000 French words in its vocabulary it often sounds to the untrained ear that those speaking it are flitting between the two larger languages in any given sentence; a glorious eccentricity that I found myself mulling over as I drove through the stunning Ardennes, a seemingly never ending expanse of rich, dense forest that stretches and undulates across Belgium and into Luxembourg, the fresh smell of wet pine courtesy of the rain storms stretching across Western Europe thick in the air.

Dudelange lies at the southern tip of Luxembourg, a small picturesque town that huddles beneath the imposing St. Martin church at its centre, its twin spires jostling for supremacy with a huge water tower that once used to stand among large factories and mines on the far side of town.

This friendly, sleepy place doesn’t feel like a natural venue for European football’s second largest club competition to begin its ten-month journey to a showcase final in Basel, Switzerland that will be watched by millions worldwide.

But that is what makes the qualifying rounds of the UEFA Europa League so special; long before the big names come along to take the main prize, a glut of teams unknown outside their home town get to participate, get to belong to a prestigious competition, and celebrate the successes that enabled them to qualify – celebrate their pride in their club, their town, their community with an intensity and passion just as great as those that make the final. That Dudelange is a part of this celebration, even though the rest of Europe will take little notice of this, or any of the other first qualifying round fixtures, is what makes these competitions so vital. Just because their club, their town, their community isn’t very big doesn’t mean it isn’t just as important as that of Manchester United, Barcelona, Bayern Munich. It may not seem it if you have never been to such an early fixture in the competition before, but if you had happened to be at the Stade Jos Nosbaum, Dudelange, for F91 Dudelange’s match against University College Dublin on a balmy early July evening, or any of the other countless first qualifying round fixtures across Europe that day, then you would know differently.

F91 Dudelange was formed in 1991 when Alliance Dudelange, Stade Dudelange (who were represented in that Luxembourg squad of 1982), and US Dudelange merged in the hope of creating a more financially and sportingly stable club. All three had won the Luxembourg national league and cup in the past, but all had fallen on hard times, and it wasn’t until the year 2000 that the new F91 finally put the long-term decline of its predecessors behind it by winning the league.

Given the size of the country and the size of the town, which could be explored in its entirety in a couple of hours on foot, it seems amazing that it could have supported three teams for as long as it did.

From high up on the observation platform beneath the head of the water tower, Dudelange fanned-out around the church and the small town centre, before quickly becoming over-run by the deep, rolling forest that stretched over the hills beyond.2

A short walk from the water tower takes you out to where the forest had reclaimed the open mines that once formed a large part of the town’s industry. Such a small town surrounded by such verdant woods made you wonder just how many years it would take for it to swallow Dudelange too, if kept unchecked. Not many.

F91’s adventures in Europe began in 1993 with a 7-1 aggregate defeat to Maccabi Haifa of Israel in the now defunct European Cup Winners Cup, followed the next year with a 12-2 defeat at the hands of Ferencváros of Hungary.

It wasn’t until the first qualifying round of the Champions League in 2005 that F91 finally won a European tie, equalising in the last minute away to HSK Zrinjski Mostar of Bosnia before scoring three unanswered goals in extra time that sent them through to the second round and a 9-3 defeat by Rapid Vienna. Only once have F9I gone beyond the second qualifying round of any of the European club competitions, when a victory via away goals against Red Bull Salzburg in 2012 saw them lose 5-1 to NK Maribor in the third round.

The club are no strangers to European football, albeit only at the early qualifying round stages; their 1-0 defeat to UCD in the first leg the week before being their 47th match in Europe since the club were formed back in ’91. But despite the regularity of their appearances in European competition, it was clear to see that the pride in qualifying for it still hadn’t waned.

Walking up through quiet, tidy, narrow residential streets the morning of the second leg against University College Dublin, the Stade Jos Nosbaum, which sat on top of a hill overlooking southern Dudelange, hidden by a small wall at the end of a cul-de-sac, was busy with volunteers making the final touches ahead of their big night.

A small army of volunteers, all well into their ’60s and no doubt retired, swept the small main stand, an exposed stretch of blue seats that basked in the sun on the far side, and raised the flags of Luxembourg, Ireland, and UEFA as well as a flag promoting respect on four flag poles by the entrance. Others slowly moved the sprinklers that were watering the pitch from spot to spot, or pushed trolleys of food and drink for the kiosks. The place was quietly bustling with excitement at the prospect of another night of European football, and they smiled and nodded as I took pictures, showing me where I could buy my ticket later on, happy to let me wander about their field of dreams.

It is an idyllic spot for a football club, and it is easy to see how such devotion as displayed by this small band of old-timers can manifest itself; the pride in their club, their stadium, their town apparent in the beautifully hand painted club badge mural on the wall above the rows of blue seats, the immaculately tended wooden framed main stand, the carefully displayed photographs, pennants and scarves of previous European fixtures on the walls of the small fan shop. This was their Nou Camp, Old Trafford, San Siro, only smaller, anonymous.

The Stade Jos Nosbaum was not my first Luxembourg football stadium visit. No, the pull of that programme from 1982 had been strong; the fascination of wondering about the likes of Progres Niedercorn, Stade Dudelange, and the Luxembourg national team itself (that had lost that match at Wembley 9-0, which remains to this day the nation’s heaviest international defeat) had compelled me to ask my parents if we could make a short detour as we drove across France one summer for a camping holiday near the German border, showing on the map how close we were to Luxembourg and their 15,000 capacity national stadium.

To my amazement they thought that was fair enough, which was how I found my 12-year-old self pressed up against the gates of the Municipal Stadium, peering intently at the patch of seats that I could make out across the pitch, wondering at the thought of England, Germany, and Italy playing here as well as matches between Avenir Beggen, Juenesse D’Esch and Red Boys Differdange. No longer was the thought of these tiny teams an abstract one; here was the home of Luxembourg football, here was their version of Wembley.

I took some very bad pictures with my wind-on camera, trying to take shots between the bars of the main gate, but invariably just taking close ups of the gates themselves. Either way when they were developed the better ones were kept safe; they still are a memento of my first ever taste of football’s minnow community.

The thrill I felt standing at those gates, of seeing abstract made real, of having the peace and quiet to experience the scene while my parents and sister sat patiently in the car felt just as intense as when I used to do the same thing at The Dell, Southampton, during the summer months of the off-season.

If we went in to town we would always have to stop off at my spiritual home of football to see if I could spend any of my pocket money on programmes or player photographs from the season just gone, and if there was time I would snatch a few moments pressed up against the locked turnstile gates, trying to catch glimpses of the pitch and the stands through cracks in the old wooden doors; the drone of a lawnmower as the groundsman tended the pitch, the slow rumble of cars creeping past, distant echoes of children playing drifting across the cramped terraced streets beyond.

That quiet moment, where I had the entire ground all to myself, where I could look, absorb it all without the bustle and necessity to keep moving on a match day because of the crowds, those hushed few moments felt special, looking on my first love in a way most people didn’t. The rows of old wooden seats beneath the shadow of the West stand, the sun-drenched terraces. For one small moment I got to see them, really see them. They had seen so much through the years, had survived, just, the blitz of World War Two, had been the heart of the town, the community, for more than eight decades.

The fact that I felt just the same levels of electricity, awe, coursing through me in Luxembourg as I did at home helped me realise that, though I loved my team and the big time of the first division, so too did I love the small time teams, the obscure. They felt just as vital, just as important, and I needed them in my life just as much.

If F91 are long in the tooth when it comes to European football, then University College Dublin is still very much taking baby steps.

There can’t be very many University teams that can lay claim to having ever played European club football, but UCD’s US style scholarship scheme that enables players the chance to combine study for a college degree with playing senior football has enabled a select few to do just that.

Since 1979 when the college scheme was set up upon entry to the League of Ireland Senior Division UCD have made three adventures into Europe, their clash with F91 Dudelange being the third. In 1984 they came away with a very creditable 1-0 aggregate defeat to FA Cup winners Everton in the European Cup Winners Cup, and in 2000 they lost on away goals in the Inter Toto Cup to Velbazhd Kyustendil of Bulgaria.

Their 1-0 home victory over Dudelange in the first leg created history as their first ever European success, despite reports that the team from Luxembourg absolutely battered them looking for an equaliser; inspired goalkeeping by Niall Corbet and lady luck saw them bring a slender lead in to the away leg.

This feat is made all the more remarkable because UCD were actually relegated to the Airtricity League First Division, the second tier of senior Irish football, in 2014, only gaining entry into the Europa League via the UEFA fair play table, and even then, they didn’t win that – they came third, behind St Patricks Athletic and Dundalk, but as they had already qualified for this season’s European competitions UCD claimed the spot.

It may not be the most traditional way of securing European football, by being successful in domestic league or cup competitions, but as UEFA explain:

The fair play assessments are made by the official UEFA delegates on criteria such as positive play, respect of the opponent, respect of the referee, behaviour of the crowd and of the team officials, as well as cautions and dismissals.

It is hard not to want clubs that consider such levels of respect to be the norm, to have their day in the sun as a reward for upholding all that can be great about the game. UCD’s small but loyal fan base used to include, until his untimely death, the actor Dermot Morgan, who played the wonderful Father Ted in the show of the same name. When asked why, of all teams, he chose to support UCD, the legend goes that he replied, ‘Because I hate crowds!’

Whether he would have enjoyed this Europa League qualifier therefore, as 1,200 people began to fill the compact Stade Jos Nosbaum, will remain one of life’s great unanswered questions. As the small band of students that followed their team way out to the Grand Duchy began to attach their Irish flags to their corner of the main stand, and sit in the heat of the day drinking beer, you can’t help but imagine that he most probably would have.

From the sun drenched blue phalanx of uncovered seats that ran the entire length of the pitch opposite, watching the shadow of the odd cloud undulate across the vast expanse of rolling forest on the hills beyond the water tower, it seemed a ludicrous notion for anyone to not appreciate such a blissful spot. Yes, the 1,200-crowd made this tiny ground seem very full, but the relaxed atmosphere that enabled young children to have a kick about between the milling throng at the kiosk selling beer and sausages, the warm handshakes between UCD and F91 supporters as they huddled around the small fan shop looking at pennants and pin badges, would surely have made even Father Ted at ease.

To be one of the very few UCD supporters that could say, ‘I’ve seen my team play away in Europe’, something only a few have the honour of boasting, would have been worth a bit of shoulder jostling while queuing for a glass of Bofferding, Luxembourg’s home brewed beer. And as both teams came out on to the pitch the fervour with which the UCD scholars greeted their team suggested they were going to make the very most of this rare opportunity.

On paper, as with the first leg, UCD seemed up against it; a collection of students from the second tier in Ireland playing against a side with four senior internationals in their line-up. Jonathan Joubert, Tom Schnell, Daniel Alves Da Mota, and David Turpel all had lots of experience playing against the world’s best for Luxembourg, who were placed 146 in the FIFA rankings.

The team, and the supporters, who shielded their eyes from the sun with a newspaper come match programme given out free at the entrance, seemed very quietly confident of turning the 0-1 deficit around, and their team’s composure and skill on the ball in the opening minutes, where they restricted UCD to snatches of possession, seemed to back up everyone’s positivity.

Unfortunately for the team and their fans, they hadn’t quite counted on UCD’s resilience.

After close to 20 minutes of constant pressure, UCD broke down yet another attack by F91 and scurried off on a rare counter. Catching the F91 defence cold they tore down the right wing, and a couple of passes later Ryan Swan, the goal scorer in the first match, swept home another to put the students two up on aggregate. Beer, flags, newspapers are flung into the air like the entire away section have just plummeted down the steep face of a rollercoaster ride, and the students on and off the pitch went ballistic. Stunned silence descended around the rest of Stade Jos Nosbaum, and it is only stirred back into life when a couple of minutes later a UCD defender is sent off for what looked like an innocuous 50-50 challenge.

Suddenly, with more than 60 minutes remaining, and despite their twogoal lead, the tide seemed to have turned in F91’s favour. They had dominated play when UCD were at 11, now they were one down it was true backs-to-the-wall stuff from the Irish. Last ditch tackles, desperate clearances, and an ever-increasing string of spectacular saves from the hero of the first leg, Niall Corbet, kept UCD ahead until right on half time when, as the board went up to announce three minutes of added time, F91 midfielder Joel Pedro struck a long-range screamer that no keeper in the world was going to stop right in the top corner: one all on the night, 2-1 on aggregate. And before the home supporters could find their seats, Dudelange tore at UCD from the kick-off, forcing a corner from which Kevin Nakache powered a bullet header into the roof of the net; 2-1, though UCD’s away goal still gave them the advantage as the half time whistle went.

But to the fans slumped in the away end and to the UCD players trudging off toward the tunnel with sagging shoulders, that slender advantage seemed as good as useless; UCD had run themselves into the ground trying to make up the superior technique and man advantage of their hosts, and they had conceded twice. Ahead of them lay an entire second half to try and do the same, but this time they couldn’t afford to let in any more.

With the sun seeming to be growing stronger, sapping at already tired legs, the students’ task seemed almost futile; to the home fans at least, who seemed relaxed once more as they went for more Bofferding, confident that the second half would be a formality.

So what happened next came as a complete surprise. The second half began in a relatively sedate manner, with Dudelange confident that the goal would come, passing the ball about with ease in front of UCD, who would drop all bar one player onto the edge of their penalty box whenever the hosts encroached too far, tackling ferociously to preserve their lead with Ryan Swan, their sole attacking player chasing down any clearance UCD’s flat back eight made, trying to take it into the wings until help came.

But as the half progressed and the students tired beneath the hot sun, F91 stepped it up, launching attack after attack, smacking one long range shot against the bar, fizzing others narrowly wide, forcing Niall Corbet into fingertip save after fingertip save.

In front of him the students’ tackles became more desperate as the host’s advances became more dangerous. UCD bodies threw themselves in front of shots, made last ditch tackles before somehow recovering to hoof the ball down field, praying Swan might be able to latch onto the odd one, and try and take it as far in to Dudelange territory as possible to waste a bit more time.

The minutes ticked by painfully slowly for the visitors as legs began to cramp, and the skill of F91 created opportunity after opportunity. Never, I imagine, had 45 minutes felt so long to the UCD players who knew that if they could hold on, they would create a small slice of European history. History that would create precious few ripples among the wider European football community; but for them, for their club, it would mean everything. However, even among the desperate tackles and lung bursting runs to close down F91 attacks, UCD allowed a little bit of slapstick, a moment of physical comedy that wouldn’t have looked amiss in an episode of Father Ted, and would have made their most famous son roar with laughter.

As the clock slowly wound down, and yet another attack had been repelled, UCD found themselves with a throw in on the half way line in the shadow of the main stand. One UCD player slowly retrieved the ball, holding it above his head as if to take the throw-in, before allowing it to drop behind him and he jogged back on to the pitch. A second student took the ball up, held it above his head, looking for a player to throw too, before he too let the ball drop behind him, and ambled back on to the field. With howls of derision raining down from all sides of the ground, the F91 bench gesticulating to the referee, a third UCD player took the ball up, feigned to drop it behind his head too before smirking and throwing it down the line; a tiny moment of magic direct from Craggy Island itself.

The talent of F91, with all its international experience, passed and probed and attacked mercilessly, making every UCD player go far beyond whatever levels of pain and exhaustion they thought possible. Every threatening pass was countered with a lunge tackle and clearance, every run down the wing covered by a student shadow boxing the step-overs and trickery of a Dudelange attacker, every cross powerfully headed away, long minute after minute after minute. And when all that failed there was Corbet in goal to pull off another save at full stretch.

Five minutes of added time at the end added insult to injury, as the students fought off attack after attack, but finally, finally, as the referee blew his whistle one last time those added minutes of excruciating toil only served to heighten the ecstasy, helped embellish the heroism of the UCD ten (14 including the three substitutes and young Sean Coyne who looked to have been sent off unfairly), adding to the legend of the battle of Dudelange. The impossible had happened; through guts and determination they had survived.

As the students celebrated on the pitch and in the stands, some of the backroom staff and various club officials stood in floods of tears, hugging one another in disbelief at what had been achieved, at being a part of the first ever UCD team, a team playing in the second tier of Irish football, to win a European tie. The small band of away fans in the quickly draining main stand jumped up and down, unsure what else to do, and as the sun slowly began to set on this picturesque little ground, in a picturesque little town in this lush, forested spot in southern Luxembourg, they knew they had witnessed their own little European miracle.

It may never be heralded like Manchester United’s come back in the Champions League final of 1999, or the miracle of Istanbul that Liverpool instigated in 2005, but this anonymous little fixture, hidden among a great many other anonymous European fixtures at this embryonic stage of the competition, provided a display of heroism and bravery the like of which I hadn’t seen for a very long time. That it was only witnessed by 1,245 people is immaterial.

To those who were there, they’ll know, no matter how painful it may be to the vast majority, a number of whom sat quietly in their seats, in shock, long after the final whistle, so confused by what they had just seen, their team so dominant in almost every aspect. They had dismantled UCD in every technical aspect of the game, the only thing they hadn’t broken was their determination, their bravery.

As the supporters drained away beneath a setting sun, slipping away into the quiet streets, only a couple of turns of which and the compact Stade Jos Nosbaum disappeared from view as if it had never been there, those same old-timers from the morning began to lower the flags, empty bins, sweep the stands with far less vigour than they did earlier, their European adventure over for another year.

It’s not so much defeat that hurts these long-time volunteers of F91, after all supporting Dudelange, supporting Luxembourg, being the perennial underdog, you must grow accustomed to losing; it’s more that this year, this fixture, for the first time in a very long time they weren’t the underdogs. They had been the bigger and better team. But it just wasn’t to be.

At least there would be next year, though no consolation right now, because surely this team would be good enough to remain at the top of the domestic league, ensuring another crack in a year’s time. As I wandered about the now near deserted Stade Jos Nosbaum, watching the old-timers at work, I certainly hoped so.

For F91 Dudelange there would hopefully be next year. For University College Dublin there would be, probably against even their wildest dreams, next week, and a trip to Slovan Bratislava in the second qualifying round, where they would ultimately lose 1-0 before a 5-1 defeat at home sent them out.

But for now, for one night, they could allow themselves a moment of celebration. A celebration their supporters embrace fully, as a group of four students weaving away down the street drunk on success and Bofferding ask each other two questions in broad Irish accents:

‘Where the hell is Bratislava?’, and ‘Where can we get some more of this Bofferding?’

For them it was going to be a long night. For their club it was a night that will never be forgotten.

And that I think is the point.

Great stories aren’t just the preserve of football’s elite. The soul of football plays itself out wherever there is a scrap of land, a battered old ball, or 1,200 people in a small stadium in southern Luxembourg. In fact, the soul of football can be far more easily discovered the further from the elite level you travel, where barriers between player and supporter, clubs and those that love them don’t exist. It is a vibrant, exciting place, and how many other stories like UCD’s would be played out across this one night of Europa League first qualifying round football? How many more acts of devotion by untold volunteers in preparing their spiritual homes for its big day; how many more tales of die hard supporters travelling to far flung regions of the continent all in the name of the club they love?

We will never know. But out there a precious few do, and that is what really matters. And thanks to one old programme from 1982, given to me by my Grandad that set me on my way, I felt very happy knowing that I had, finally, become one of them.

1 Joaquin Alonso Ventura, nicknamed ‘La Muerte’, The Death, became a fitness instructor and English teacher when he retired, but not before winning the CONCACAF Champions Cup with Aguila, also of El Salvador, in 1976 in an interesting fashion. After routine wins over Aurora and Diriangen of Nicaragua, and fellow El Salvadorians Alianza, they beat Leon of Mexico in the semi-final 3-1 on aggregate. With Leon leading 2-1 from the first leg, the return tie was abandoned after a fight broke out on the pitch, resulting in Aguila being awarded a 2-0 victory and passage to the final where they defeated the wonderfully named Robin Hood or Suriname eight three.

Joaquin’s international team-mate Mauricio Quintanilla, or El Chino, despite featuring in the sticker album, narrowly missed out on the ’82 World Cup squad, but did go on to earn five caps for his country as well as win the Guatemalan league title in 1980 with Xelaju before returning home.

Jasem Yaquob scored 34 goals for Kuwait and played from 1969 until retiring in 1983 for just one club, Al-Qadesseyah where he won the Kuwait Premier League six times, and the Kuwait Emir Cup four time.

Ernest Lottin Ebongue played in all three of Cameroon’s World Cup matches in ’82, and was capped eight times in total for his country. His career took him to France where he played a season each for AS Beziers Herault in 1986 and US Fecamp in 1987, before a season with Vitoria Guimares in Portugal in 1988, three with fellow Portuguese side Varzim, and two shorter spells with Desportivo Das Aves and Lamego.

Ernest finished his career in Indonesia where he spent four years playing for Persma Manado and Pupuk Hactim. Preceding all his travels Ernest won the Cameroon Premier Division three times with Tonnerre Yaounde, but arguably his greatest achievements came for his country at the ’82 World Cup and the Africa Cup of Nations a decade later where he scored his only international goal in front of a partisan 35,000 crowd in Dakar, in the quarter finals against hosts Senegal.

2 The water tower housed an extraordinary exhibition of haunting pictures taken during the great depression in the United States in the 1930s. Row upon row of nameless, destitute people, their lives of hardship and struggle etched into their expressions materialised out the gloom of deliberately ill-lit spaces. Their bleak, helpless resignation at their inescapable fate seemed at home in the dark silence of a gallery; these faces lingering as you stepped blinking out into the day on the observation platform at the top. The collection, entitled ‘The Bitter Years’ was the last exhibition organised by Edward Steichen as director of the photography department of New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. Steichen believed them to be ‘the most remarkable human documents ever rendered in pictures’. As a gift to his homeland, he requested that the images be bequeathed to the Luxembourg government in 1967.

CHAPTER 2

If Football Shirts Could Talk – Palestine

Part One – back to 2003

IF FOOTBALL SHIRTS could talk what stories might they be able to tell? Potential answers to the sports eternal mysteries that seem destined to remain locked within the confines of dressing room walls, turning to myth with the passing of time.

If they could what might they be able to say about the goings on in the Colombian dressing room minutes before their last group match at the World Cup in 1994? What could they tell us of rumours of threatening phone calls from drug cartels, an unfortunate own goal resulting in the South Americans early exit from the competition, and the subsequent assassination of Andres Escobar, the scorer of that own goal?

What of the goings on before the World Cup final four years later? What really happened to Ronaldo? Did Nike force the Brazilian management to play him regardless of him having a seizure?

What could they tell us of the dynamics and power struggles between countless big name players and managers throughout the decades?

But personally, a far more important story that had haunted me for more than a decade, a story far from the bright lights of the World Cup, a story with so much more to tell, if the shirts could only tell me, would be what became of the wearers of an old amber and black kit, liberated from a life destined to fester in an English attic in 2003, and re-invented as the training kit of the Palestinian FA’s Gaza based under-15 team?

All these years later, after well over a decade of war, deprivation and suffering, where might those shirts be now, and more importantly, what became of the young boys that wore them?

But first, how did a football kit that had long been forgotten in a loft on the outskirts of Southampton get there, to Gaza, one of the most dangerous places on earth, in the first place?

In 2001 I began raising funds to start a team that would be called Druk United in the little known and very poor Buddhist country of Bhutan, high up in the Himalayas. Short on resources and money, it proved a rewarding experience providing children with a chance to access kit and coaching, to play the game they loved, and which resulted, 14 years on with one of the team’s players representing his country in their first ever World Cup qualifier in Sri Lanka, before going on to captain the side against Hong Kong and The Maldives.

With all the extensive fundraising I managed to accumulate bags and bags of kit that enabled even more groups within Bhutan the chance of having a kit of their own. Some also found its way to Montserrat, Bhutan’s opponents in an international friendly played in 2002 and captured in the inspirational film The Other Final.

And then there was a bag of old amber and black kit, won for a couple of pounds on eBay, left over after all the other parcels had been sent on their long Himalayan or Caribbean treks. What to do with that?

Palestine, like Bhutan, was, and still is, a country desperately lacking in sporting resources. But unlike Bhutan, whose geographical isolation bars easy access to facilities just as much as its economy; the eternal Arab-Israeli conflict, with economic blockades into Gaza and aggressive Israeli incursions in response to mortar fire from Hamas positions into Israel, (that in turn are retaliations to oppressive Israeli policies that can all too frequently descend into all-out war) keeps the football community of Palestine, and especially those of The Gaza Strip, living off of scraps and in horrendous conditions.

Regardless of political leanings and thoughts on one of the most divisive issues in the world, the simple bond of empathy that can be created between one football fan and another can often elevate itself high above the realities of centuries of unrest. Knowing the joys that our game can bring into our lives, the escape from the everyday, the ability to dream, to live out our dreams, it is easy for someone that has it all to want to help those with precious little, and the people of Gaza have exactly that. A set of old, unwanted shirts, though very small and insignificant in the scheme of things, well it was something where often there could be nothing.

Palestine and all its hardships seemed as good a recipient for this old kit as any, and after some very vague emails to the only contact details of the Palestinian Football Association that I could find, I received a reply from Jamal Zaquot, General secretary of the PFA, who said the boys’ team from Gaza would be very happy to have it, providing an address in the Gaza Strip where the kit could be sent.

Looking at those lines of text that made up the address I wasn’t entirely confident that any parcel sent to it would make it through the various borders and check points and blockades that separated Palestine from the outside world. But send it I did, and a couple of weeks later came back a letter of thanks confirming it had arrived safely, and a number of small photographs, indistinct and hazy, their contents fragile, washed out, like partially developed Polaroids that only hinted at the larger picture around them. They were photographs of the boys training in the kit at a deserted, sun bleached stadium somewhere in Gaza.

Despite having received similar pictures from all over Bhutan and Montserrat in the previous months, it never stopped feeling surreal to witness shirts that had been piled in one corner of a spare room having new life breathed into them by grateful recipients across the globe.

That a set of kit that had been sat in someone’s loft for who knows how many years had found its way to one of the most war-torn spots on earth, and was enabling children that had to survive among it all to play the game they loved is a hard notion to fully absorb, to properly comprehend. And like the pictures from Bhutan, these photographs from Palestine found a safe resting place in an old scrapbook, to help keep their meaning, their contents safe.

And there they stayed, though the faces that looked out from them endured, and kept coming into sharp focus every time another news story appeared about the tensions in the Middle East.

With the significant language barrier (Jamal had communicated with me using his broken English, my Arabic being non-existent), as well as the extreme lack of resources, limited windows of communication, political tensions that closed borders and shut off basic amenities, and the almost constant threat of all-out war, something as simple as a list of the boys’ names that featured in those photographs, where they lived, what they hoped to become, seemed all but impossible in 2003, and even more so now, all those