Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Honford Star

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

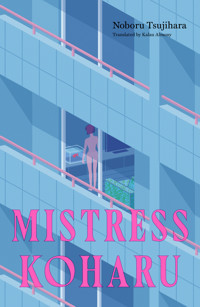

An obsessive Tokyoite Pygmalion—thrilling and provocative literary fiction from a leading Japanese author. Akira, a meticulous editor at a major publishing house in Tokyo, harbors a secret: he lives with Koharu, a Hungarian-made love doll. Each night, he speaks to her and finds a long-sought solace in her presence—a comfort he cannot attain even in the arms of real women in his life. Things only improve when Koharu breaks free from her role as a love doll and starts speaking and moving on her own, transformed into the perfect wife. But when a new woman enters Akira's life, everything changes. A single confession to Koharu about his attraction sets off a chain of disturbing events that spiral into the unexpected.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 335

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

12

Mistress Koharu

NOBORU TSUJIHARA

Translated by Kalau Almony

Contents

Part One

7

1.

Upon returning home a little after 10 p.m., Yano Akira opened his bedroom door and, without turning on the lights, whispered, “I’m home” to Koharu, who was sitting up, leaning against the headboard. Koharu squirmed ever so slightly, glanced at Akira, and gave him a small nod. Akira shut the door with bated breath and walked to the living-dining-kitchen at the end of the hall.

Akira lived in an apartment in a five-story building. He did not own but rather rented it from a real estate corporation, which had acquired the apartment as an investment. It was, in Japanese real-estate parlance, a 1LDK—a single bedroom and a combined living-dining-kitchen space—and was far from large, just forty-five square meters, but for a single man like Akira, the layout was perfectly livable. On the left of the hallway leading from the entryway was his bedroom and a small spare room he used for various chores; on the right were the bathroom and shower, divided into separate rooms. At the end of the hallway was the combination living-dining room and kitchen about ten tatami mats in size, and in this living-dining-kitchen was a large closet.

Before turning on the room lights, Akira approached the aquarium on the left of the closet and asked, “How are you doing?”

The tank was lit by a small clip-on light. The two red and white sarasa comet goldfish waved their long, flowing tails and 8raced to the surface of the water, opening and shutting their mouths in anticipation of food. In response to Akira’s call, the pure red ranchu emerged from his usual position in the crevice between the base of the heating cord and the corner of the tank, moving in a gentle, clockwise spiral. It was three years ago that he had brought these fishes home from the large plastic viewing tanks of Kingyozaka, a goldfish specialty shop in Hongo.

After Akira fed the fish, he watched the three of them swim back to their usual positions, and once they had returned, he shut off their light and covered the tank with a blackout sheet before switching on the lights of the living-dining-kitchen.

Akira approached the window and opened one of the sliding glass doors that led to the balcony, letting in the night air. The apartment had been shut up all day, and he wanted to air it out. He had left the front door half open for that purpose as well.

Below the balcony was a municipal park for young children. If one were to draw an oval within its rectangular grounds, it would probably produce a track of about 150 meters. Across the now barren and blackened park, the playground equipment and low trees cast tentative shadows. In the middle of the park was a pond with a fountain, but Akira had not once seen the fountain spitting water.

About forty meters away, on the opposite side of the park, stood a ten-story Leopalace apartment building. At this hour, Akira thought he could connect the dots of the few room lights still aglow and wind up with a constellation he knew. The wind blew through his apartment, and once Akira felt the air had freshened up, he closed the glass door and then closed and locked the front door as well. 9

Akira had moved into this apartment in Nishi-Kanda five years ago, when he was thirty-four. Prior to coming here, he had spent twelve years in the company dorm for single men in Mejirodai, near his workplace. The super there called him “boss.” Next year he would be turning forty, but he was still completely unattached. No one around him had brought up talk of marriage recently, and he had no intention of looking for someone to marry either, so it was probable that his life as a single man would continue. His father had lived for a long time as a widower in Minoh, one of Osaka’s satellite cities, and would be turning seventy this year.

Akira took a can of Guinness from the refrigerator opposite the kitchen sink, checked his mail, and read the evening paper. After finishing the beer, he made himself a Tachibana Genshu on the rocks, a sweet potato shochu he had ordered from Kuroki Honten distillery in Miyazaki.

Sitting on the couch, Akira turned on the TV. The NHK-BS1 news broadcast had just started; they were announcing today’s opening of a new extension to the Hokuriku Shinkansen bullet train line, which would connect Tokyo and Kanazawa. The trip would take only two hours and twenty-eight minutes! The newscaster added that the line was expected to be extended to Tsuruga in Fukui by 2022.

Akira remembered traveling around the Noto Peninsula one winter in his mid-twenties. Back then, he had taken the Joetsu Shinkansen to Echigo-Yuzawa Station and changed trains for the Hakutaka Express to get to Kanazawa. It had taken over four hours. He was shocked by how much faster the trains had gotten.

As the clock struck twelve, he turned off the TV, showered, 10changed into his pajamas, brushed his teeth, and headed to the bedroom.

Akira turned on the floor lamp to the right of his bed, removed Koharu’s dress, helping her strip down to just her lingerie, and positioned her face up on the mattress.

He climbed over her, and from her left side, leaned on top of her, his right hand massaging her thigh and buttocks as he rubbed his face in her breast.

Koharu was a life-sized love doll Akira had had delivered from a gallery in Koganecho in Yokohama’s Naka Ward. Such dolls used for sex were once called “Dutch wives,” but the term “love doll” had come into general usage to denote a Dutch wife made with realistic detail.

Akira graduated as a literature major from the humanities department of his university, with his undergraduate thesis on Chikamatsu Monzaemon, the playwright of bunraku puppet theater and kabuki plays. Even before this doll arrived, he had decided that he would call her Koharu—the name of the heroine of Chikamatsu’s TheLoveSuicidesatAmijima.

After he began living with Koharu, Akira made a discovery. Something unrelated to the workings of sex, something to do with sleep.

The expression “Dutch wife,” the predecessor of the term “love doll,” came from Dutch-occupied Indonesia, where Dutchmen sought to improve their troubled sleep in the hot tropical nights by sleeping with body pillows made of bamboo. These “bamboo wives” inspired the name of the dolls later made for sex. And what Akira discovered was that, when he slept spooning with Koharu, she served to drastically improve his sleep. 11

He found that when he went to bed with any part of his body touching Koharu, he would fall into a deep sleep such as he had never before experienced. Moreover, he had completely stopped dreaming.

Akira’s bedtime ritual began with petting then advanced to him telling stories. Problems at work, memories from his childhood, gossip about friends; the talk would continue endlessly, and Koharu, an excellent listener, would nod her head, give simple responses, and touch his body at just the right moments. Akira would grow relaxed, overcome by a warm and gentle feeling.

Akira worked in the editorial department at a large publishing house of both books and magazines, and tonight he couldn’t help but let the complaints spill from his mouth.

“Printing ran late again today. The editor should have marked the author’s corrections on the galleys and handed those over to the printers, but she just gave them the galleys with the author’s notes attached. The operators had to do twice as much work, and the way they mark corrections isn’t even the same.”

“Is it that woman editor again?”

“Yeah, did I tell you about her? The new girl who started last year. I don’t know who trained her, but they don’t seem to have taught her anything …”

Koharu pushed her right breast against his left arm, and Akira tried to continue his story with his eyes closed, but there was nothing he could do to fend off the sleep that suddenly overcame him. After dropping off for just a moment, he woke again, and though he felt aroused at Koharu gently stroking his penis through his pants, sleep came and dragged him back into its depths. 12

2.

When he was a student, Akira encountered the work of manga artist Tsuge Yoshiharu. As with many Tsuge fans, he first read ScrewStyleand then began collecting all his major works. After landing his current job, Akira learned that Tsuge had once serialized his diary in a literary magazine, and so, for a hefty price, Akira purchased on Amazon a used copy of the hardcover edition of TheDiaryofTsugeYoshiharu.

TheDiarycovers five years, beginning in 1975 and ending in 1980, though there are at times significant gaps between entries, and the work is filled with the details of the manga artist’s daily life. It begins with the birth of his son and goes on to capture on page his wife’s battle with cervical cancer, the couple’s disagreements, the deaths of friends, memories of a discontented and oppressive childhood, and complaints about his incapacity to create new work.

Tsuge was haunted by an incomprehensible anxiety, and beginning in the second half of TheDiary, mentions of that anxiety grow frequent.

“It’s not that I grow anxious about some imagined problem; rather I’m in a state where I’m anxious about anxiety itself. Sometimes I feel as though the only escape from this anxiety will be death.”

One day, on a walk with his four-year-old son, Tsuge suffered a sudden episode of some sort and collapsed in the park grass. There, lying on his side, he followed his son’s movements with his eyes, his own body stiff and trembling.

The Diary ends on sports day of his son’s preschool. 13

Akira read the book in one sitting. In the afterword, Tsuge wrote that he was encouraged by his editor’s flattering claim that his diary “is actually an I-novel,” but Akira felt that the work possessed a charm different in nature from the so-called I-novel of Japan. He remembered the feeling he had after reading the book: it was as if in one corner of a dark and gloomy sky there had opened a gaping mouth of blue.

When Akira discovered that the author Tomioka Taeko had written about this diary, he searched the office library for her essay.

The piece was titled “Personal Life and the I-Novel,” and was in Tomioka’s essay collection TheSceneofExpression. In the opening she touched on how Tsuge mentioned his editor complimented him by saying that his diary was like an I-novel, and then she drew attention to Tsuge’s understanding of his own work as an I-novel. She argued that unlike the I-novels that came before it, Tsuge’s was not premised on the intention to express the self through fabrication, and she went on to claim that the unostentatious style of the work was the result of Tsuge’s optimistic belief that one could both maintain the purity of their “personal life” while also making themself into the subject of an I-novel.

Additionally, she wrote, “Whenever I think about the ‘novel,’ I imagine a scale with ‘I-novels’ in the Tsuge style on one side and ‘allegory’ on the other. These two are polar opposites, and the ‘novel’ must not go to either extreme; it must fluctuate between the two sides. Maybe it is because his illustrations are a form of allegorical expression that his written work tends towards the opposite extreme.”

As Akira looked over the other essays contained within 14TheSceneofExpression, he noticed a piece titled “Curses and Reproductions.”

Tomioka Taeko begins “Curses and Reproductions” by citing an interview with a “Dr. S” published in the May 1984 issue of PhotographicEra. After witnessing the suicide of a mother of a disabled child and seeing families collapse under the pressure of raising disabled children, Dr. S, a neurosurgeon, decided to create a Dutch wife for mothers and children. Dr. S proposed this unexpected solution after coming face to face with situations where the male child’s sexual desire was directed at the mother.

After many prototypes and failures, Dr. S managed to produce one thousand dolls which he believed would be effective as partners for disabled people. Dr. S called those dolls his “daughters,” and he is quoted as saying that “those who have requested one of my daughters must choose auspicious days for the occasion of receiving her” and that he truly felt as though he were sending daughters off to get married.

This was when Akira first developed a strong interest in the Japanese-made Dutch wives, called “sex dolls” in English, twenty-two years after Tomioka Taeko wrote this essay.

Tomioka noted the measurements of Dr. S’s “daughters.” According to the essay, they were 158 centimeters tall, with busts of 88 centimeters, waists of 60 centimeters, hips of 89 centimeters, and weighed 7 kilograms. Their skin was made from 100% latex, and the subcutaneous fat of rubber. When he looked this up online, Akira found that these types of dolls were now primarily made of silicone.

In terms of its texture, elasticity, and translucency, silicone was the material that most closely resembled human skin, and 15it could be used to reproduce even the most delicate features of the human body.

Further, contemporary dolls had frames made of stainless steel, industrial plastic, brass, and aluminum, and as their joints were made of fiber-reinforced plastic, their shoulders, groin, hips, and knees could all be moved freely.

Akira had imagined a love doll shrugging and smiling, and he thought to himself that at least once he’d like to see a real one.

While online, Akira had stumbled upon Orient Industry. Of the handful of love doll makers within Japan, Orient Industry was the oldest and largest, the premier brand. Because, at the time, Akira lived in a dormitory for single men, he wouldn’t have been able to bring home a love doll. However, Orient Industry had a showroom and took reservations for tours. Out of curiosity, Akira had headed to their showroom in Okachimachi.

Over fifty dolls had been on display, dressed in a variety of fashions and striking a range of poses, and while Akira did find some charm in their deportment and construction, he did not find a doll whose face he liked. The heads were connected by joints and interchangeable, but they all looked like characters from comics or anime and were made up like popular idols; they had felt quite distant from his own preferences.

At the recommendation of an editor who joined the publishing company at the same time as him, Akira had watched the film Cape Fear, directed by J. Lee Thompson, starring Gregory Peck and featuring Robert Mitchum in the role of the unforgettable villain. Akira fostered a secret adoration of the actress Lori Martin, the only daughter of the lawyer played by Peck—and he had hoped for a doll with a similar, daintily featured face. 16

After the tour of the showroom, Akira continued to browse the webpages of love doll makers and maniac fans, and among them he regularly visited a certain connoisseur’s webpage called Taa-bo’s Dress Up Reference Room. And though his interest in love dolls never waned, he never encountered a doll that made him take the leap and make an actual purchase.

Then a few years after leaving the dormitory, in the fall of 2014, he had happened upon a youth magazine’s special issue on love dolls. One of the articles in the issue said that Gallery Hitogata in Yokohama’s Naka Ward held a biannual exhibition and sale of love dolls assembled from around the world. The owner of the gallery was the manager of a major restaurant in Chinatown, and he collected love dolls for his personal amusement.

So twelve months ago, mid-December 2014, Akira exited the gates of Keikyu Hinodecho Station and headed for Gallery Hitogata. As he had previously researched, the gallery was located below the Keikyu Main Line that ran alongside the Ooka River, halfway between Hinodecho Station and Koganecho Station. This area used to be a red-light district, overrun with prostitution and drug trafficking. However, the commencement of a construction project to repair and reinforce the elevated Keikyu Main Line in case of earthquakes triggered evictions of the shops and residences under the rail line, as well as the establishment of the Koganecho Area Management Center, a non-profit organization with the goal of beautifying the area.

As part of their activities, in 2011, the organization established a new facility called Konagecho New Studio Beneath the Rails in the one-hundred-meter space below the train 17tracks between Kogane Bridge and Suekichi Bridge. The facility combined gallery spaces, shops, studios, and meeting rooms.

Gallery Hitogata was housed within that complex. Akira walked along the footpath between the tracks and the river, searching for the gallery.

Konagecho New Studio Beneath the Rails was a long, two-story, rectangular glass box stuffed beneath the train tracks, and Gallery Hitogata was on the second floor. On the first floor was a used bookstore, Artbook Bazaar, which specialized in art books.

Akira climbed the wooden stairs, then, walking along the glass wall, made one pass of the hallway before opening the door of the gallery. There were no other visitors. A small, fat man built like a penguin who, like Jean-Paul Sartre, had a lazy right eye approached him. He said something to Akira, but as a train passed overhead just as he began to speak, Akira couldn’t catch what he was saying.

The man introduced himself as the gallery manager and politely led Akira to the display space. The floor was covered in the same wood as the hallway, and aside from the entrance, all the walls were glass, with off-white lacquered boards positioned to block the sun—and people’s glances—from the outside. Soft downlighting illuminated the small space, where fifteen or so dolls striking various poses lay in wait.

“Our specialty is foreign-made dolls,” the man said in a whisper. “These are mostly from America, from Abyss Creations in San Marcos in Southern California. This company doesn’t call their products love dolls, but ‘RealDolls.’”

Akira looked at the dolls one by one. Both the build and 18makeup of these dolls, which were clearly made for American tastes, made Akira deeply uncomfortable. Their breasts and butts were emphasized to the extreme, and all together they felt forbidding to him, the thickness of their eyebrows and plumpness of their lips simply abnormal. Were they supposed to look like some Hollywood actresses?

After looking over about two-thirds of the dolls, Akira had begun to lose interest. Then, when he arrived in front of a doll sitting on a stand in the corner of the display room, he stopped in his tracks.

This doll had an entirely different aesthetic from those made by Abyss—she had short, black hair, and looked undeniably Asian. In English, one might call someone with her clearly defined features a handsome woman. Yes, she was without question a handsome doll.

She was wearing a purple cotton dress. It fit her loosely, and the hem came down far enough to cover her ankles, but the sleeves were short and tied back at her elbows. The whole dress was embroidered with colorful flowers and trimmed with white lace; it made Akira think of the traditional clothing of some Eastern European tribe. The fabric had faded slightly, which exaggerated the yellowing of the lace.

“The gallery owner purchased this one. According to him, this doll was made in a studio in the suburbs of Budapest, Hungary. Supposedly the posthumously discovered work of the legendary doll-maker Giuseppe. The ancestors of the people of Hungary were originally Asian nomads, so I imagine that explains how she acquired such a face.

“This doll had been sent to St. Petersburg in Russia as part of 19a special exhibition; the owner picked up whatever dolls didn’t sell. He got her along with two French dolls. Here, the French dolls sold right away, but this one …”

Once again, a train passed overhead, cutting off their conversation.

“The owner said she had a nickname in Russian, and that name translates to something like ‘leftovers.’”

Here the manager’s story veered further off the tracks.

“I’ve heard there is a small village north of St. Petersburg, where every year they host a Dutch wife river race. Contestants race inflatable dolls down the rapids of the local river. Occasionally, there are even deaths.”

Akira hadn’t just liked the looks of this doll. With just one glance he had felt somehow that they would be able to talk to each other, that they’d get along. He was drawn in by the intense magnetic force she was emanating, but he did not mention this to the manager.

“Why hasn’t anyone wanted to buy her?”

“A black-haired Mongoloid in Russia? And in Japan, it’s her size. She must be about 165 centimeters tall. They make all the dolls smaller here. There are optimal proportions for dolls, you know. At Orient Industry, all the dolls are between 148 and 155 centimeters tall, their busts are …”

Akira recalled a television show he saw on Animal Planet about dog shelters in America. Since it’s generally assumed that big, black dogs don’t find owners, they are all put down.

After taking a perfunctory look at the remaining dolls, Akira returned to the Hungarian-born doll. He took a photo of her and then asked, “Can you please take off her clothes?” 20

3.

Upon deciding to purchase the doll, Akira asked if there was anything to prove it was actually the work of the famous artist Giuseppe, some sort of product guarantee. The manager said that unfortunately he had no such documentation, but proceeded to take out a handwritten memo left by the gallery owner. Indeed, the name “Giuseppe” was written where the manager indicated. The manager attached a red ribbon saying “Sold” to the embroidered breast of the doll and whispered, “Congratulations.”

After processing the payment on Akira’s credit card, the manager handed him a pamphlet for first-time doll purchasers, clearly just put together and printed out on the office computer, titled “Dear New Love Doll Owners.”

Akira returned home, and, using the photos he took in the gallery, identified the embroidered pattern on the doll’s dress as a traditional Hungarian design known as Matyo embroidery. He learned Matyo was the name of a region approximately 130 kilometers east of Budapest, said to be the poorest area in all of Hungary. There, the majority of residents worked in agriculture and were, uncommon in Hungary, primarily Roman Catholic. The patterns of the embroidery were known for their use of roses, birds, tulips and other sumptuous motifs, and in 2012 it was registered with UNESCO as a form of intangible cultural heritage.

Akira began to read “Dear New Love Doll Owners.”

CAUTION!!!

Tight-fitting clothing and wire brassieres may damage your doll’s supple skin. 21Dark-colored fabrics (black, red, purple, brown, blue) may transfer color to your doll’s skin.High-heeled shoes increase risk of falls.Changing your doll’s clothing is a constant challenge. Front or back fasteners are fine for clothing on the upper half of her body, but you cannot use side fasteners. However, skirts that fasten to the side present no problem.When posing your doll, poses such as holding the doll’s arms above her head, standing the doll straight up or at attention, squatting the doll excessively low (or raising the knees high in a sitting or lying position), or squeezing the doll’s breasts together may put excessive force on the silicon, causing rips or damaged joints.[…]

Recommended Clothing

Camisoles and fabric brassiere sets. Stretch fabrics, thin knitwear, and jersey items.For sexy options, consider a set with an open top and miniskirt or string bikini swimsuit.Only use fingerless gloves. It is difficult to insert the doll’s fingers in regular gloves.The Hole/Misc.

Included in your purchase are two types of Japanese-made holes (genitals): opened and closed types. Please consult with a love doll maker for specific questions about their use. All makers offer a wide selection of parts which can easily be purchased individually.[…] 22

Thank you for your purchase. We appreciate your patience as you wait for your doll to arrive.

Sincerely,

Gallery Hitogata Manager

It would be over a week before the exhibition ended and the doll would be sent to Akira’s apartment, so he spent the time with fashion magazines and mail-order shopping catalogues spread across his coffee table. Until now, he had never paid much attention to women’s clothes. In all his time working in magazines, he had never once handled a woman’s magazine.

He used the magazines and catalogues to gather basic information, and then on the weekend he went out to department stores and boutiques to make his actual purchases. He purchased a cashmere tunic coat, a wool one-piece dress, lingerie, panty stockings, socks, shoes, scarves, accessories such as earrings and necklaces, a parasol for the sun, and considering the possibility that he might take her for a drive, sunglasses and masks as well. Once, he even paused for a second in the department for menstrual products.

In two or three of the stores, female staff gave him strange looks; they must have been wondering if he was a crossdresser. Akira also bought thicker curtains to replace the ones in his bedroom, which had been hanging there since he had moved in, and replaced the mattress and sheets of his king-sized single bed.

At the end of the year, a large, heavy, rectangular cardboard box arrived. The box was plain, and the packing slip listed the product name as “furniture.”

After much struggling, he was just barely able to get the box 23through the door to his bedroom. From within the thick, double-layered cardboard, emerged Koharu, still dressed in Matyo embroidery. Akira lifted her up, laying her across his arms, and carried her to the bed.

Paying careful attention to the range of motion of her joints, he delicately bent and arranged her arms and legs, removed her dress, carried her to the bathroom, and gave her a shower.

Her skin was smooth, youthful, and a brilliant white. He dressed her in the lingerie set of lace-covered silk shorts, a brassiere, and a slip and leaned her in a relaxed position against the headboard of his bed.

In the pamphlet he had received from the gallery was a warning that if you leave the doll in a position that creates wrinkles in the crotch, stomach, side, or back of the legs for an extended period of time, it may cause cracks to form when repositioning, so it was best to leave the body in a wrinkle-free position as much as possible. Take care not to forget that her body is made of silicone, the pamphlet reminded.

There were tears and frayed spots on Koharu’s dress, and it smelled of mold. When he tried washing it by hand in the sink, the water turned blackish red from the dirt and dye. After he dried the dress out, he sent it for the most expensive cleaning option at the dry cleaners, and when it was returned he hung it in the closet along with her other clothes.

Akira did not dislike these little chores. In fact, they allowed him to demonstrate his attentiveness and dedication, and he took them up eagerly.

He was, however, soon met with a surprise. About ten days after her arrival, some oil-like substance began to leak from the surface 24of Koharu’s skin, dirtying her shorts and underclothing. When he emailed the experts at Orient Industry asking what was wrong, there came an immediate reply. This was a phenomenon known as “bleed”; the oil added to soften the silicone was leaking from the surface of the doll. The oil should be removed with a cleaning product such as Magiclean. The doll should then be showered, thoroughly dried off, and dusted with baby powder to prevent further bleed. The baby powder will not only give the doll’s skin a human-like feel, but also prevent the buildup of static electricity and the collection of dust. The response from Orient Industry included a postscript mentioning that when all the oil had left the doll’s body, the silicon would harden and the doll would have reached the end of its life.

The love doll’s eyes could be moved, as could its tongue. The mock genitals were called a “hole,” and there was an empty space to insert that hole in Koharu’s nether regions. There was also a part called a “hole cap” that was to be inserted to prevent wrinkling in the crotch area when a hole wasn’t in use.

When she arrived, the empty space in Koharu’s crotch was stuffed with high-grade cork. The standard-type holes included in the packaging were so carefully constructed, Akira found himself transfixed.

Usually, there was only one empty space in a love doll’s crotch for inserting a hole. To create another one in the rear to replicate an anus was considered technically difficult for structural reasons. Inclusion of such a space would inevitably lead to weakening of the groin region and the hip joints.

Koharu, however, had two spaces. This, Akira had seen with his own two eyes when he had the manager of Gallery Hitogata undress her. 25

From the beginning, Akira’s sexual relations with the doll were simple, vanilla. While he found pleasure in missionary and doggy style, he did not attempt any risky positions such as cowgirl.

In his first few days of living with Koharu, a sense of familiarity of the sort he’d never felt before took shape within him, and Akira was struck by a premonition that their relationship would grow to be a close one. His sense in the gallery that they’d make a good match must have been correct.

While he bathed the doll, patted her down with baby powder, and changed her clothes, he would talk about whatever trivial matters came to him. That was good for his mental health, and he discovered the importance of having someone who would listen to his troubles.

“There’s a branch of a university hospital near my office, and in the lobby there, there’s this coffee vending machine. It was on that variety show Tokoro-sannoMegaTen!on Nippon TV. Sometimes on my way back from lunch I get a jumbo-sized mill-ground coffee mocha for 280 yen. There’s one with eleven grams of sugar, and one with sixteen grams. I always get the eleven gram one with cream. For a vending machine it takes a while for the cup to come out, but while you wait it plays that song ‘Coffee Rumba’ by Nishida Sachiko: ‘Longago,agreatArabmonkgaveasadmanwho’dgivenuponloveanamberdrinksorichin smellittingles…’It’s nice to listen to that song while you wait for your coffee. There are a couple of other fans of this vending machine in my office as well.” 26

One night, about three weeks after Koharu had arrived, Akira stopped by a bar in Jimbocho before heading home. After he showered, he laid on the bed and while touching Koharu’s chest said, “Last night on NHK they played an episode of the travel documentary ShinNihonFudoki, I think it was the one called ‘Osaka Babe Ruth.’ I had it recorded. The backing song was by Ueda Masaki, and it was about the people living near Osaka Harbor, people from Okinawa and barge families, fishermen who worked in the mouth of the Yodo River. I thought it was a good show.”

Unprompted, he started telling a story he had heard from his father.

“My family is originally from Ikeda City in Osaka,” he began. “When my father was in elementary school, sometime at the start of the third decade of Showa, my grandpa took him to see his great-grandfather’s house in Fushiodai in Ikeda. It was this enormous house, all fenced in, and with this great kabukimon-style gate, a wooden one with a crossbar on the top that sticks out on both sides. On the other side of the trees in the garden, my father could make out the second story of the wooden house. Then they went to see a nearby temple where my grandpa played when he was a child. But the temple was abandoned and no one was there. There was a placard with a list of all the people in the neighborhood who had donated money to the temple, and they found my great-grandpa’s name there and how much he had donated.

“My grandpa passed away when I was eight, in Minoh, Osaka. When I was three or four he’d let me sleep in his arms, and he always sang me Osaka bedtime songs or lullabies or whatever 27you want to call them. ‘Akira/StartswithA/Anjuro/Ants a-hoisting / Aren’t they? / Aren’t they?’ And it goes on, but that’s all I remember. It was like a spell or a curse or something, when I’d hear it I’d get so, so sleepy.”

Koharu, who had been lying beside him, lifted up her body and repeated,

“Ants a-hoisting / Aren’t they? / Aren’t they?”

Akira was drunk. He broke into a full grin and said, “Amazin’. You memorized it!” in his Osaka dialect. In the moment, he did not find it the least bit strange that Koharu had risen and begun speaking on her own.

4.

Yano Akira began working at the publisher in 1998, just two years before what was widely perceived as the end of the twentieth century and the start of the new millennium. The following year, the publisher would begin publication of a partwork—a publication released in sections—called Record of the 20th Century. They planned to release one volume a week for each year of the century, covering the history of the twentieth century in both Japan and the rest of the world.

Incidentally, the twentieth century actually started in 1901, not 1900. The first century began in year 1, and thus its final year was year 100—the year zero did not exist, and thus the new millennium would actually begin in 2001.

After completing his three-month training period, Akira was assigned to the editorial department, as he had requested upon hiring, and began working as the assistant to the two editors 28in charge of Recordofthe20thCentury. His work consisted of proofreading—comparing the proofs against original texts and correcting any typos or other errors, while also keeping an eye on the factual accuracy of the content.

Akira acquired basic editorial skills such as how to use correction symbols and handle first and second drafts. He also learned how to collect the necessary materials for editing and fact checking historical texts, registering as a user of the National Diet Library in Nagatacho for this purpose. He would keep note of the content that he couldn’t satisfactorily check with the materials in the company library and, once a week, make his way there.

As this particular partwork was a graphic magazine using photographs to illustrate wars, disasters, changes in customs, and other important incidents, the quantity of photographs they could collect would be key in determining the quality of the work. Therefore, the editor of each issue worked with specialized staff gathering photos, and they amassed an enormous collection of historical images. On occasion, rare, once forgotten photographs were rediscovered through the process.

Once, Akira discovered a black and white photo of a meeting of the Imperial Council at the Imperial Palace printed backwards in a second draft, and he just managed to replace it in time, averting certain catastrophe. The writer of that article had joked that “a car full of far-right protesters were already on their way,” and was so relieved the mistake was rectified that he took Akira to a restaurant in Kagurazaka and treated him to dinner.

That same writer also shared with him several stories of his hardships searching for photos, including one occasion he 29worked on a column in Recordofthe20thCenturythat was titled “Nippon from the Outside.” This column was about how Japan and the Japanese were seen by people from other countries, and in the middle of each article there would be a photo of the face of whichever person’s perspective was being described.

In the 1913 (Taisho 2) issue, the column’s subtitle was “Shogun Nogi Through the Eyes of a US Newspaper Reporter.” The topic was how Stanley Washburn, a twenty-six-year-old special correspondent for the ChicagoDailyNews, saw Nogi Maresuke, the general in the Imperial Japanese Army who famously led the 1904 (Meiji 37) attack on a Russian military detachment in Port Arthur.

Washburn’s best-known work was the book Nogi:AManAgainsttheBackgroundofaGreatWar, and the magazine writer explained to Akira how he had to find a photo of this journalist’s face. However, no matter where he looked, he couldn’t find any publication in Japan that had run a portrait of him. He could have reached out to American media, starting with the Chicago DailyNews, but there was simply no time. The writer was under pressure and spent several nights visited by nightmares where the column, with an empty space where the photo should have been, came chasing after him.

One day, as he worried himself, he had a sudden flash of brilliance and recalled that he had heard the U.S. Embassy in Akasaka had a wealth of materials relating to America. Though he may have been grasping at straws, he called their publicity office. The voice on the other line asked if he knew the date of Washburn’s death, and after answering, he was told to try checking the obituaries of the NewYorkTimes, as that paper was well known for publishing photos of the deceased. 30

Upon hearing that, the writer darted from his office and rushed to the Diet Library, where he finally found a photo of the young Washburn, and was also shocked to find that the library had complete archives of not just the New York Times but also the Times, LeFigaro, and numerous newspapers of record from around the world.

After his time on this partwork project, Akira worked on men’s weekly magazines for quite some time before being assigned to a men’s monthly, where he was faced with a certain situation that bothered him.

That monthly poured a lot of resources into their nonfiction pieces and wasted no effort on developing their writing talent. One day, when he was editing an article on the Glico-Morinaga Incident, Akira’s eyes stopped on a passage. The Glico-Morinaga Incident began in Nishimiya City, Futamicho just after 9 p.m. on Sunday, March 18, Showa 59 (1984) when a group calling itself “The Monster with Twenty-One Faces” raided the home of Ezaki Katsuhisa, the forty-two-year-old president of food company Ezaki Glico, and kidnapped him.

The passage in question read, “The gang infiltrated the house through the servant’s door using a spare key and quick as the wind raced up the stairs of the Ezaki residence to the bedroom on the left side of the stairway.” However, this depiction, in a piece which attested to be nonfiction, sparked a deep suspicion in Akira. It described how the criminals moved through the house as they searched for Katsuhisa, who was on the second floor bathing with his children, but no one had actually witnessed this scene. 31

There were several other sections that repeated this sort of imaginative depiction, and each time he found one he left a Post-it with a simple comment, but when Akira checked the revised manuscript, the writer had ignored all of his notes and the piece was published as it was.

For Akira, the question of whether a writer of nonfiction can use their imagination and insert such suggestive passages between the facts soon grew into a larger question. Whether nonfiction or otherwise, all writing must necessarily take the form of a narrative. Therefore, did this not then mean that the adding or subtracting from the facts to create structure and the incorporation of the writer’s own biases and flourishes always happened somewhere in the background of a piece of writing? And was this authorial intervention not also a sort of black box, impenetrable to readers who have no means of evaluating the function and extent of the author’s imagination?

An inspiration for this question were the crime novels Incidentby Ooka Shohei and VengeanceisMineby Saki Ryuzo. Akira harbored the suspicion that when the authors wrote these crime novels—both based on real incidents—they were actually doing the same thing as nonfiction writers. He felt that the presumption that the use of imagination increased as one moved from nonfiction to fiction based on true events, then further increased as one moved to wholly imagined fiction, was both naïve and contrived.