20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

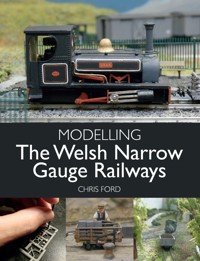

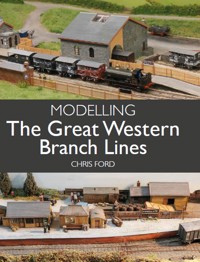

Modelling the Great Western Branch Lines is essential reading for all those who wish to build a model railway based on the branch lines of the Great Western Railway. The author guides the modeller through projects which are graded from simple to more advance. Each step is clearly described, explaining the techniques used and how alternative methods and materials could be employed. Topics covered include an historical overview of the subject; full listings of all tools and materials; a series of detailed model projects using the best of the currently available commercial model making products; an introduction to scratch-building lineside terms and, finally, suggestions as to how each project could be further developed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 275

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

MODELLING

The Great WesternBranch Lines

CHRIS FORD

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

© Chris Ford 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 566 4

Dedication

For my Father, Raymond Ford

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the following: Michael Farr, Simon Hargraves, Nigel Hill, the Bala Lake Railway, the Severn Valley Railway, Didcot Railway Centre, the Bodmin & Wadebridge Railway, Crawley MRS.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER TWO: SELECTED HISTORY

CHAPTER THREE: GOODS TRAFFIC

CHAPTER FOUR: COACHING STOCK

CHAPTER FIVE: APPROACHING ABSORBED ROLLING STOCK

CHAPTER SIX: BRANCH-LINE LOCOMOTIVES

CHAPTER SEVEN: MAIN BRANCH-LINE BUILDINGS

CHAPTER EIGHT: GWR SIGNALS

CHAPTER NINE: BRANCH CATTLE TRAFFIC AND AN INTRODUCTION TO ETCHED KITS

CHAPTER TEN: SMALL BUILDINGS AND ANCILLARY EQUIPMENT

CHAPTER ELEVEN: PLANNING YOUR LAYOUT

CHAPTER TWELVE: EXHIBITING YOUR GWR BRANCH LAYOUT

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: CONCLUSIONS

INDEX

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

The ‘typical Great Western branch line’ is the way that countless model railway layouts are often described. This only comes second to the term ‘classic’. When applied to descriptions of a model, the reality and irony is that neither ‘typical’ nor ‘classic’ is an apt description for what usually follows, which can often veer worryingly towards the unrealistic and the twee. There is, of course, nothing wrong with these slightly twee creations, which can, and do, give a vast amount of pleasure to the builder and the viewer alike. The Great Western Railway (GWR) branch-line model can be quite emotive for these very reasons, creating equally reactions of joy and total derision.

The truth is that in model terms it has over time become regarded as something of a cliché, far more than other similar branch-line models, and has resulted in a stream of repetitive models that are almost carbon copies of earlier examples. These frequent statements of Great Western layouts being clichéd are somewhat unfair, as although the Great Western Railway models may well be more numerous, the accusations of twee and unrealistic can in reality be levelled at any similar model of any railway company, without exception. And as the real thing drifts back further and further into history, the copying of other models will surely become ever more prevalent, as this is all the research that most people will bother to undertake. This slim volume is unable to fill these gaps in research in anything like a full and conclusive way, but hopefully more than anything else, it will nudge the reader into investigating some of the history of the Great Western branch system in a deeper fashion than may have previously been the case. If this happens even in a small way, then the book will have been deemed to be a success.

The classic and typical Great Western branch engine in the shape of a 45XX Small Prairie Tank. The numbering of GWR locomotives is confusing, but each class is usually referred to by the initial number of the class even if that bears little resemblance to the number on the cab plate. Here, number 5572 rests at Didcot Railway Centre.

THE GREAT WESTERN BRANCH AS A SUBJECT FOR A MODEL

Why then is the GWR branch such a popular subject? There could be a number of reasons.The first is that more than likely to many people the GWR branches ran through some of the most beautiful scenery in the British Isles, although this could be countered by the fact that every British railway company was in the same situation. If this was a primary reason, models of the West Highland Railway in Scotland would outnumber anything else by ten to one. Secondly, it may be the attractive green locomotives with the gleaming copper fittings hauling chocolate and cream coaches, but in human terms we are fast losing anyone who can actually remember that scene in real life and much of the Great Western Railway’s money was made hauling dirty coal trains out of South Wales and transporting goods toward and away from the ports of Bristol and the Mersey. The third and more likely reason is that not only was the Great Western the country’s longest lived and physically largest rail company, invoking a certain local pride in those who lived in its area, but the model trade and press has pushed the Great Western like no other line throughout the history of commercial model production, making it almost the default entry point for any modeller coming to the hobby during the last sixty years. This makes it the most straightforward for the novice, as there is just so much available with a Great Western slant. It is only in the last decade or so that the other three 1923 Grouping companies (the London Midland & Scottish Railway, the Southern Railway and the London & the North Eastern Railway) have had anything like as much attention from the model manufacturers.

Another classic in model form, the 14XX 0-4-2 tank. This is a Hornby model (ex-Airfix) shown here as it comes, straight from the box. The prototypes were originally numbered in the 48XX and 58XX ranges, but the 48XXs were renumbered after World War II to 14XX and the entire class is usually referred to in this way, even the pre-war examples.

WHAT SCALE?

At the time of writing, there are some nine suitable ready-to-run (RTR) locomotives for a Great Western branch-line layout, and that’s just in 4mm scale (OO gauge). There are a similar number of coach designs and the list of suitable wagons in RTR or kit form is simply endless. All that from current new product manufacturers, without starting to access the buoyant second-hand market. The situation in N gauge is similarly good, with four or five locomotives to get you started, but a little less in the way of rolling stock. The range of locomotives in 7mm scale (O gauge) is greater, although these are in the main in kit form and are not necessarily aimed at the novice. However, there is no reason why someone armed with a basic toolkit and plenty of enthusiasm shouldn’t try one of the excellent Springside Models locomotive kits for the scale. There is recently, though, a sudden push to produce RTR locomotives and wagons in the larger scale and the modeller with even a modest amount of cash could now view this as a good entry point. The general understanding is that 7mm scale is almost four times the size in area terms as OO, so much less is needed to make the same visual impact, though naturally there is a little more baseboard area required for even a modest layout.

All in all, there is no excuse for not building a GWR branch-line layout and every reason to feel enthused by the sheer avalanche of material that will pour out from your local model shop. In fact, it is more than possible to build the layout purely from commercial shop-bought items, especially as in recent years there has been an explosion in the availability of ‘ready-toplant’ resin buildings … at a price. These buildings are somewhat expensive when compared to the equivalent plastic kit or scratch-built structure, so if finance is a concern, there are large savings to be made by doing much of this work yourself. However you wish to approach this and whatever your skill level, putting a GWR layout together is by far the most straightforward route to an attractive and accurate model branch line in any of the popular scales.

WHY A BRANCH LINE?

In historical model terms, branch lines always came in second place to the glamour and speed of main lines, but sometime around the late 1950s to the early 1960s there was a shift in the general approach. This was largely triggered by the hobby becoming generally cheaper to enter. Beforehand, it had been the preserve of those who were financially better off and the models reflected this. Much of the rolling stock consisted of high-value items made by toy manufacturers in Germany, or hand-crafted at great expense in the UK – definitely not the playthings of the lower-middle and working classes. Then three things gradually happened: the prices of the models came down; the hobby was marketed as something for the ‘aspiring and upwardly mobile father and son’ to do (a gender-specific ploy that would definitely be frowned upon today); and in Britain the scale shifted downwards from the usual O gauge to something closer to what we know as OO, making these newer small-scale models affordable to the masses. The young family could now afford the train sets, but did not necessarily have the available requirements in domestic space. The idea was put forward that the best way to proceed was to build a compact branch terminus. This could be worked up whilst you gained confidence and acquired rolling stock, at which point the layout could be expanded (presumably when you moved to a larger house) to the large main-line layout of your dreams.

The social-climbing aspirational desire of the postwar masses was not lost on the model-makers and the idea of the pure branch-line model gained a traction that has remained ever since. The unforeseen outside factor during this post-war period was the rapid closure of the prototype branches by British Railways at around the same time, further prompting interest in rural branch lines that before had been regarded as not worthy of notice. As the branches closed, so the interest in preserving them in model form grew. The final piece in the jigsaw was probably the work of one man, Cyril Freezer, editor of both Model Railways and Railway Modeller. He promoted the idea of the Great Western branch line as an ideal with almost religious zeal. The model trade recognized the trend, duly followed, and the cult of the GWR branch in model form was complete.

Many of these reasons for choosing to model a branch line still hold true today, to some extent more so, as the size of the standard British home steadily reduces. The ‘build a branch – expand to a main line’ course of action will certainly still work now, but whereas previously the result could be quite crude with little in the way of scenery around the railway, we can now easily produce a high-quality model that will far surpass anything that could have been produced in 1960.

Here, an N gauge GWR layout shows how compact a terminus station can be. This model is built in the space of 45 × 12in (1,143 × 305mm).

The other modern development which could not have been foreseen in the early days of modelling has been the rise of the model railway exhibition as almost a hobby in itself. Every weekend, a travelling circus of modellers gathers in halls of various sizes all around the country to display their layouts. This also plays firmly against the idea of the large main-line layout. These certainly do exist, but they are generally set up and operated by large clubs, are transported there by van and take a goodly while to erect. More common is the smaller group or individual who turns up in a private car with, what else, but the GWR branch-line terminus in OO or N scale – the ultimate in portable model railways. In the 1950s and 1960s, the idea was centred around cost and fitting something into a small bedroom. In the twenty-first century, it is very much about what will fit into the family car; though in the end it all comes down to desire verses practicality.

WHAT SORT OF BRANCH LINE?

So let’s assume that you have decided on a branch-line model and also plumped for the Great Western as the company, but what sort of branch do you want? Many of the answers to this will be expanded upon later in the book, but here are a few initial ideas. Due to its size and longevity, the GWR was highly diverse. The usual way of thinking is to build a branch terminus station with a platform, a goods shed, an engine shed and a signal box. Bear in mind, though, that this was far from a standard set-up – many termini did not have engine sheds, some had only rudimentary goods facilities, while a few barely even had platforms. The reason for this is that the GWR acquired several independent and minor lines over the years and these were far from consistent in their build and shape, making the design of branch stations far from standard.

Lastly, there is an historical angle. Most model GWR branch layouts tend to be set firmly in the mid-1920s to World War II period, but if you were to drop this dateline back ten or twenty years, things start to look quite different, featuring outside-framed locomotives with open cabs, Crimson Lake coaching stock and even red-oxide wagons with heavy timber framing. Travelling back into the nineteenth century would give an entirely different view and you could even take on the challenge of the Great Western’s broad gauge, of which more later in the book. This very lengthy possible timescale makes the Great Western unique, as no other British railway company existed with unbroken working and management structure from the early Victorian age through to World War II.

This Kitson-built 0-4-0 was absorbed into GWR stock when it took over the Cardiff Railway, where it worked the lines around the docks in the city. The GWR owned many such small shunters, built for and used in similar circumstances.

PLANNING YOUR LAYOUT

All of this can involve a large degree of planning and careful study. You may, of course, just lift a printed plan out of a book or a magazine and run with it exactly as presented. This approach will often work well, but bear in mind that some paper plans do not allow quite enough space, so do check that it will work before you start building. Many a layout has been abandoned through not building a simple mock-up with a few points and crude card buildings to establish that the plan will actually do what it suggests. Also, most published plans are already physically compressed for the modeller and will probably not take any further reduction.

Bob Vaughan’s highly detailed and compact OO layout ‘Condicote’. Note that almost everything in this scene save the platform is a commercial item, readily available at all model shops. This demonstrates that even though most are not marketed as Great Western, with skill and practice a very convincing scene can be achieved and will reflect a GWR atmosphere with only small amounts of visual information. Only the van, the coach body and the pagoda building are GWR designs, yet the viewer is fooled into thinking the whole is typical.

Unless you are very confident, be careful not to overreach at this stage. A small, fully worked-out layout plan that is able to be finished in a reasonable amount of time is better than a grandiose room-filling idea that will never have a chance of getting done. The key point is often to work out as part of the scheme how much time you realistically have available, as this is probably more important than the layout plan itself. It doesn’t matter how many or how large a plan you dream up in your head during your working or commuting hours. If you only have twenty minutes of spare time a day outside of work and family commitments, then a big layout simply will not get done. It is a far better policy to start small, pace yourself, and build something that can be regarded as finished within a reasonable amount of time. A project that is likely to take longer than a year to complete will quickly lose inertia and will become a millstone, rather than a pleasure.

Tip

Spend plenty of time deciding what you want to achieve in terms of scale, period and size of the overall project before you buy too much or start work on a layout.

HISTORICAL PROTOTYPE RESEARCH

Unless you are desperate to get started straight away, doing a little prototype research will be time very well spent. This could be nothing more than a little casual browsing through some of the mainstream model magazines such as Railway Modeller or Model Rail, or it could be something much more academic and organized. A very brief general history of the GWR follows in the next chapter, but as a gentle preamble there are a couple of points to consider. Firstly, the layouts in magazines have a habit of replicating themselves and this is where the problem of the GWR branch line being a cliché tends to emanate from. While it’s wrong to criticize other people’s modelling work, it is often hard not to wonder if the builder has looked outside the modelling catalogues and magazines at all, such is the repetition of ideas. The defence for this is that in many ways the GWR is just as much an historical experience as, say, the Tudor period, so other people’s models tend to become the pattern. We are now at the point in time where there are few who can remember the pre-World War II era, so we are reliant on contemporary film footage and photographs in exactly the same way as we are reliant on documents and artefacts from the Tudor 1500s – and that is where most of the problem lies. We readily accept that everyone carries some sort of camera now, but although cameras were available in the 1920s, they were still very much a luxury item. Add to that the high cost of film compared to the throwaway digital format, and the subject matter chosen by the photographer became much more prone to natural selection. In other words, if you were going to photograph a train, it was likely to be a big, glamorous example and not a small, grubby train on a branch-line goods service. Therefore, what does exist photographically in spades is the record-breaking express, but much less of the ordinary working branch-line trains.

The suggestion for the novice is to start collecting some of the picture-album books that refer either to the GWR as a whole, or specifically to the area being modelled. The second-hand market often turns up books from the publisher Bradford Barton. These are useful, as they are comparatively contemporaneous with the end of steam in the UK. However, this can offer up traps, as while branches were notorious for keeping the same running style beyond World War II, it is usually only the locomotives (albeit reliveried for British Railways) that remain from pure Great Western days. There was a dramatic change in wagon design post-war, and often as not the coaches too were upgraded from the 1930s types, so a little thought is required before taking the photographic evidence as typical for the pre-war period. The newer versions of the Bradford Bartons are the books from Middleton Press, which deal with the railway system almost line by line. These do occasionally feature pre-war images, but they are mostly very up to date and therefore useless for our needs. The whole process is one of sifting through material and discarding that which has no relevance. In essence, it is pure historical research. Lastly, it is worth picking up Great Western Railway Journal, which is available quarterly from larger newsagents. It does get very detailed at times with regard to the written work – possibly much more than the novice will require – but the photographs are high quality and very useful.

The main thing that the novice modeller is looking for is the make-up of the trains in given situations for branch traffic, for instance: are the trains loco-hauled or push-pull (the locomotive hauling the train one way, then pushing on the return journey)? Are the passenger trains ‘mixed’, with wagons added? What sort of goods traffic is being carried, and so on? Also, the layout of the station buildings and trackwork should be noted. Rarely is it exactly as many of the model plans would have you believe, as these are often swayed toward using commercial track units. As obvious as it sounds, the key here is that the real railway company laid out a station to make the railway as efficient and cheap to work as possible, whereas the modeller in the main aims to add operational interest and complication to what would possibly be a very simple and straightforward working practice. This aspect will be dealt with toward the back of the book, but it is something to think about as your planning evolves.

Tip

Study the prototype first and do not base your layout purely on other people’s models.

ATMOSPHERE

What we are probably trying to gain overall here is atmosphere. This is a slippery beast and often hard to get hold of, but it can be done with a little thought. Again, there are questions to ask: Is the railway/station site rural or urban? Not all GWR branches were set in leafy countryside. Is there a single traffic that needs a specific set of buildings, such as a dairy? Are there one or more platforms and are they long or short? Several of the classic lines (there’s that description again) started their lives as light railways, such as the Culm Valley line, and had very basic platforms which were no more than 200ft (61m) long. Others that catered for big holiday crowds, such as those in the West Country, had much longer platforms to cope with large trains disgorging many passengers. These questions need to be asked quite early, as it may affect how you do something. If you already have a picture in your mind’s eye of a tiny tank engine pulling a couple of four-wheel coaches, then something like the Culm Valley or the Tanat Valley with their small, simple stations may be your ideal prototype, but if you want a more main-line feel with longer trains and larger engines, then that is going to look ridiculous in the same setting – that would need a much more passenger-heavy situation and vice versa. The railway traffic and the shape of the station site tend to go hand in hand.

The ‘typical and classic’ atmosphere beyond the trains is somewhat easier to achieve and most of it can be done with a lick of paint. This applies to any model railway really – simply study the company colours of the paintwork on the buildings and the colour of the station signage and copy it. This will get you most of the way there. In this case, the overriding scheme is to use, in the GWR’s terminology, dark, mid and light stone. The dark stone is a red chocolate brown, not dissimilar to the brown used for the coaches, and the light, a cream with a hint of pink in it. However, these colours were open to a degree of local interpretation and the further away from Paddington and the more out of the way the buildings were, the more variants in these colours could occur; often as not, the light stone morphed into a muddy cream. Signage for most of the system was usually white lettering on a black background, although again there was quite a bit of local variation.

This attention to colour and detail should provide both you and the casual viewer with an instant rec ognition of the railway company. The rule of thumb is always to be able to recognize the place and company before the trains arrive. If your model railway achieves this, you will have succeeded in your efforts.

GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY

One more thing to consider is a loose sense of geography and geology. Urban scenes are a case apart, but if your layout is country-based, it is almost essential that you consider the lie of the land: Is it rolling Devon hills? Fearsome bleak Welsh mountains? Or perhaps the much flatter Thames Valley? Even with a relatively small layout, this can be suggested quite quickly with ground contours, reinforced by a suitable backscene. Having a few visual pointers can help the trains ‘sit comfortably’ within their surroundings, making the layout feel all of a piece rather than a set of unrelated, disjointed items that look to be thrown together.

The modern preservation scene at Bodmin – 57XX pannier tank shunts its train. Note the open hatches and the riding position of the fireman – a long way from most model crew poses.

TAKING INSPIRATION FROM PRESERVED LINES

The Great Western modeller is lucky in the respect that there are several well-organized preserved lines which are either ex-GWR branch or main lines. A few of these are some of the longest in the British Isles, such as the West Somerset Railway and the Severn Valley Railway, down to short demonstration lines like the Didcot Railway Centre. All of them are very welcoming and have a good range of ex-GWR locomotives and rolling stock to study. But these preservation lines, however well run, can only hint at the sort of operation that would have taken place on the real Great Western. There are no connecting services at junctions, no porters pushing barrows full of luggage and no slow-moving goods trains clanking through the station during quieter mid-morning periods.

The approach to St Ives. The steam has long gone, but the service still remains. Replace the modern 150 unit and it is still a GWR scene from a branch worked for many years by prairie tank engines and long passenger trains.

Nevertheless, preserved lines are fine places for not only an entertaining day out, but somewhere to do a little research and to gain an insight into branch-line working. For although many of these preserved railways are sited on old main and secondary routes, the working is much closer to branch-line routine, with the same rake of stock drawn back and forth and with uncoupling and running-round taking place at each end. This preserved-line atmosphere may actually give an alternative base for a model rather than the usual pre-World War II historical approach – one that is still a GWR branch line, but set in the present day, using clean and polished preserved rolling stock.

The preservation scene is full of interest and there are gems tucked away from the main theatre. This 2-8-0 tank was designed by the GWR to haul heavy coal trains out of the South Wales coal fields and stands in the sun awaiting attention. Note the correct, but unusual, lettering style typical of the South Wales locomotive sheds.

Tip

Ensure that you always have a camera with you on these trips to record as many small details as possible. Not just the locomotives, but lamps, platform seats, buffer stops and other miscellaneous details. These are rarely recorded by the casual and family visitor, but will add to the atmosphere of your layout. The small amount of research undertaken around such items will add to the pleasure of building a layout.

SCALES AND GAUGES

At some point during the planning process the question of scales and gauges will arise. We will start with the 4mm scale, of which OO is the most common. This is actually a track gauge (the measurement between the rails) of 16.5mm. All the main track manufacturers such as Peco and Hornby use this as standard and they are largely interchangeable with each other, though there are even variations within this, with different ranges with marginally different rail heights and cross sections. If in doubt, it is probably wise to stick to the standard Peco Streamline Code 100 range, which also matches the Hornby track.

There are also two further 4mm scale gauges: P4 (Proto-four), which is exactly accurate at 18.83mm gauge, and EM (18mm) at 18.2mm gauge. Both of these require a certain level of skill and need in the main to have at least some of the track built by the modeller and the locomotives and rolling stock adjusted to match. It has to be said that there is a degree of snobbery surrounding these last two. Yes, it is trickier to accomplish, and yes, it is more accurate, but to be quite honest, 99 per cent of the population is unlikely to notice. The advice to the novice is to stick (at least initially) to OO gauge, build your first layout and worry about hyper-exact track gauges later. All the RTR models you will buy are designed for this gauge, so you will avoid an unnecessary set of problems. That is not to say that the more ambitious novice could not achieve a good result by taking this path, but just that it will take more time and if you want to make adequate progress over the mid-term, using OO for a first effort would probably be the safest route.

Below 4mm scale is N gauge. This is nominally (but fractionally larger than) 2mm to the foot, so half the size of OO in linear terms, or 25 per cent of the total area. Again, there are several track systems to choose from, the most easily available being Peco. Moving up we come to O gauge or 7mm to the foot, with a track gauge of 32mm, which is also available from Peco. Most will plump for the popular OO, but aside from the three given here, there are several ‘in-between’ scales such as 3mm scale or the old imperial measured S scale, which is somewhat larger than 4mm scale.

A comparison of two 4mm scale points (turnouts). The upper item is a very short Y from Peco, the lower is a medium-length right-hand unit in EM gauge (18.2mm). The Peco point is essentially made for the 3.5mm scale (HO) market, but has been sold as a flexi-scale item for OO for decades. Until very recently, all commercial OO trackwork was made with this market in mind.

Tip

Chat to your local retailer about the different track systems before finally deciding on which one to settle. Most new RTR items will run on the finescale track ranges, but some of the earlier pre-1990s models, such as those made by Lima, have wheel profiles that are too large. If you plan to use this age of stock, sticking to the standard Hornby/Peco code 100 rail is possibly your only option.

USING THIS BOOK

Following the next short history chapter, the book is broken up into sections dealing with a particular aspect of Great Western Railway branch-line modelling. These are not necessarily meant to be read in order – more to be picked at as the fancy takes you. They are very loosely graduated in difficulty within each chapter and there is a certain amount of technique crossover between projects, but that doesn’t mean that you couldn’t start with the trickier sections if that suits you.

There are no hard and fast rules with any of the projects. They are purely suggestions and all of the techniques are easily transferable to other similar items and, in the main, to other scales as well. Putting a plastic wagon kit together in 4mm scale as described here will transfer directly to a similar vehicle in 7mm scale. The model railway trade is notorious for suddenly taking a product off the market and some of the products used here may not always be available all of the time. It is safe to say, though, that due to the popularity of the subject, it is fairly certain that a new and similar item will rapidly become available.

Notes: The term 4mm scale should be taken to mean OO scale from this point on. The acronyms GWR or just GW (Great Western Railway) and RTR (ready-to-run) will also be used throughout the book from this juncture. Any other acronyms will be explained as they are introduced.

Metric measurements are given where appropriate, but imperial measurements are used freely, as these are historically what was referred to at the time, for example vehicle chassis lengths are almost always referred to in imperial terms of feet and inches, and it would be churlish to try to fight against this standard terminology.

Tip