23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

This invaluable book is essential reading for all those who wish to build a small, narrow gauge model railway layout to a high standard. Comprehensive in its coverage, the book begins with a useful summary of the history and development of narrow gauge railways in the British Isles, and this is followed by a detailed, but easily digestible, consideration of the complex and wide choice of scales available to the modeller. In subsequent chapters, the author covers all aspects of construction, including materials and tools, skills and techniques, layout design, laying the track, scenic modelling, painting, soldering and wiring, as well as the construction of narrow gauge stock and appropriate buildings. The author provides clear, step-by-step instructions and photographs to show the reader how to build a straightforward narrow gauge model of a fictitious late 19th to early 20th century light railway in 4mm scale on 9mm track. He also suggests how the methods he has used can be adapted to other scales and briefly explains, by way of example, how they can be transferred directly to 7mm scale. Fully illustrated with 223 colour photographs and also included are several working sketches.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

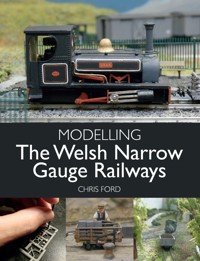

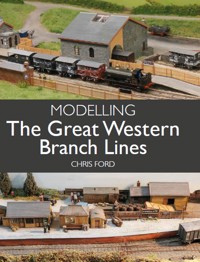

MODELLING

Narrow Gauge Railways

IN SMALL SCALES

CHRIS FORD

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Chris Ford 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 936 0

All photographs are by the author.

Disclaimer

The author and the publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, adverse outcome, or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it. If in doubt about any aspect of railway modelling, including electrics and electronics, readers are advised to seek professional advice.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the following for their assistance: Charles and Sue Benedetto, Miles Bevan, Michael Campbell, Greg Dodsworth, Stephen Fulljames, Richard Glover, Simon Hargraves, Nigel Hill, Laurie Maunder, Chris O’Donoghue, Christopher Payne, Paul Titmuss and Richard Williams.

Dedication

For Karen.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE:INTRODUCTION AND HISTORY

CHAPTER TWO:CHOICE OF SCALES

CHAPTER THREE:MODELLING ROLLING STOCK

CHAPTER FOUR:TYPICAL NARROW GAUGE BUILDINGS

CHAPTER FIVE:BUILDING THE BASEBOARD

CHAPTER SIX:LAYING THE TRACK

CHAPTER SEVEN:SCENERY FOR NARROW GAUGE RAILWAYS

CHAPTER EIGHT:NEXT STEPS

CHAPTER NINE:CHANGING SCALE

CHAPTER TEN:PLANNING FOR EXHIBITIONS AND OPERATION

CHAPTER ELEVEN:CONCLUSIONS AND FINISHING OFF

INDEX

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION AND HISTORY

BEGINNINGS

I can’t quite remember when I discovered narrow gauge railways, but the root of it was definitely a talk given by Iain Rice and Bob Barlow on ‘Light Railways’ at the Heathfield model railway exhibition sometime in the 1980s. To say that this grabbed me would be an understatement. I launched myself into finding out more about this new discovery of railways that were built outside of the normal mainline standards. This study led me straight into narrow gauge; not only were some of the lines technically ‘light’, but they had a quirky, individualistic, unusual air about them that still fascinates me to this day.

I suppose it would be helpful at this point to establish what this book is about, and if I’ve lost you already, what narrow gauge railways are. To explain in simple terms, they are railways with the gauge (the distance between the rails) set at less than 4ft 8½in (1,435mm) – a measurement that became the international standard gauge and was adopted by George Stephenson in the middle of the eighteenth century. Technically this is more of a ‘mid-gauge’ as the measurement preferred by a large portion of the west of England was I.K. Brunel’s 7ft ¼in gauge (2,140mm, or ‘broad’). This, despite having several technical advantages, had one major cost disadvantage in that passengers and goods had to be transferred whenever the broad gauge met the standard. It was this problem over all others which hastened the demise of the broad gauge, which disappeared shortly before the turn of the twentieth century, much to the disappointment of many a Great Western (and for that matter the London and South Western Railway) devotee. There are also historically, and still in existence, other gauges wider than Standard worldwide, however the only other in the British Isles is the Irish ‘standard’ of 5ft 3in (1,600mm). To all intents and purposes, this looks, at first glance, no different to standard gauge; in some cases using production body shells on wider gauge chassis units. But for now we can put all that wide gauge discussion to one side and concentrate on the narrower variety, and variety there certainly is.

The quiet inspiration. The Tal-y-llyn 2ft 3in gauge track curves around the rock face towards Towyn.

NARROW GAUGE

Just to confuse you further, there probably is (or has been) somewhere in the world, a railway gauge carrying freight or passengers measuring down at inch increments from standard gauge (4ft 8½in) down to 15 inches. There is no single definitive reason for this, though somewhere in the individual railway company’s records there will be an indication of why that line chose to build to that size. These reasons fall broadly into three camps: something existed prior to construction that made any other gauge impractical; some second-hand equipment became available that tipped the balance on cost grounds; or the engineer for the line had a personal preference, possibly based on earlier experience, and presented that particular gauge as the best option. Or it may well have been all three.

However, technically there are two reasons: geology and cost. Provided the payloads are within sensible limits, it’s generally cheaper to build a narrower gauge – the sleepers are shorter, and, provided the loads are modest, the rail can be lighter. The rolling stock can also be smaller, and less equals cheaper. The geological angle is simply that the narrower the track bed and the smaller the rolling stock, the less earth and rock need to be removed during construction and obstructions can be avoided with the use of tighter track curvature. Therefore in mountainous rocky areas there is an immediate saving on civil engineering. This can also apply on totally opposite terrain – if the ground is soft and unstable than a very small, lightweight narrow gauge locomotive is going to be a far more logical item of power than a large heavy standard gauge one.

The Lister Autotruck in its rail version. This lightweight machine was designed for working in tight spaces such as factories, or over very soft ground where a heavy locomotive would have proved impractical.

MODELLING NARROW GAUGE

These, then, are the reasons narrow gauge was often chosen over standard: it’s lighter, it’s smaller, and most importantly it works out, at least initially, cheaper to the company building the line. But why does that make it an ideal candidate for a model railway?

The answer to this question isn’t that far away from the reasons for building the real thing. Let’s start with the blindingly obvious one – it’s smaller. In a period when houses are getting smaller and smaller and the cry goes up repeatedly that there’s not enough space for a model railway, narrow gauge nearly always saves the day. Just as with the prototype, it is possible to wrap narrow gauge track around approximately half the radius of the equivalent scale standard gauge. That may not be preferable, but it is possible. Also trains are generally shorter. Twelve-coach trains are rare on narrow gauge anywhere in the world, let alone the British Isles, and traditionally here a 30-foot coach is fairly long. So, in model terms, we can halve most physical dimensions. That alone gives it an instant ‘wow’ factor to someone who is short of room. If, for example, 4mm scale is used, it would be possible to build a satisfying small layout in an area of less than 1,200mm × 600mm.

There are two other terms that don’t usually get applied to Standard Gauge – it’s cute and it’s freelance (which in this context means the adoption of an invented line with fictitious stock and livery). I will stick my neck out here and say that the former is often the primary reason for modelling narrow gauge, and the latter is usually the result, and unlike with standard gauge modelling you are unlikely to get taken to task by others for doing that. Most narrow gauge modellers freelance to a greater or lesser degree, and within modelling circles it is perfectly acceptable to do so. There are narrow gauge modellers who reside within the fine-scale ethos and do stick rigidly to the prototype, but they are rare indeed; most find a comfortable middle ground between the two extremes using a mix of basic prototype ideals, padded out with some freelance additions.

Therefore it only remains for me to say that this slim volume is designed to lead you gently into the world of narrow gauge modelling without first having to sit in a draughty hall in Sussex and without having to go through the painful process of asking the questions that I did in order to reach the grail of understanding narrow gauge, its models and all that it encompasses. Now, if you’ve got all that, it’s time for a short history lesson.

Note: For the purposes of the rest of the book I will refer to measurements in their historical context. In other words in order to avoid confusion, railways built using imperial feet and inches will be denoted as such and on the occasion when European lines are mentioned they will be denoted in their natural metric measurements. In addition the accepted standard terminology for each model scale will be used. This can be confusing to the novice, but to change to create more logical similar terms will only cause problems later.

EARLY HISTORY

So, what then is narrow gauge (NG)? As stated earlier, the answer is very simple: a railway built with the rails closer together than 4ft 8½in. But that’s not the whole story. For that we need to reach back to the second half of the nineteenth century to a couple of small slate quarries in North Wales and a man named James Spooner. Mines and quarries had long used narrow tracks or plate-ways (lines of stone laid for wheels to run along) to move mineral or waste away from the face in ‘tubs’ or ‘skips’ – small fourwheeled wagons small enough to be pushed by a man or pulled by ponies or horses. Spooner took this concept and, against the contemporary wisdom, in 1832 enlarged it to create a railway through challenging geological conditions to enable slate to be taken from the quarries above Blaenau Ffestiniog to ships at the wharves at Porthmadog on a line of 1ft 11½in gauge. The line was originally gravity worked, with full wagons rolling downhill to the port by gravity, and the empties drawn up to the quarries by horses on the return. The horses were transported back down the line in ‘dandy’ cars as part of the gravity train.

By the 1860s the traffic had outgrown this method of working, and Spooner’s son Charles introduced steam locomotive power to replace the horse working in 1863, cutting the upward journey by a number of hours. Once this North Wales precedent had been set, the concept of a narrow gauge railway as a full transport system, suited to conditions that would otherwise be awkward or too expensive for standard gauge railways took hold, and from this point until the 1920s NG railways gently blossomed alongside their bigger standard gauge brothers. While the Spooners neither invented narrow gauge nor steam-powered railways, their pioneering work in linking the two is accepted as being the point at which the concept of very narrow gauge being commercially viable and useful on a large scale began.

If the Spooner’s work in North Wales can be seen as the beginning, then two other events were to mark shifts in development: the Light Railway Act of 1896 and the First World War.

The classic Welsh slate wagon. This restored specimen is standing at Towyn Pendre station in 2013.

Ffestiniog Railway horse ‘dandy’ wagon, used to carry the animals back down the line within the gravity trains, the horse having hauled the empty slate wagons up.

Princess, one of the smaller 0-4-0 George England locomotives built for the Ffestiniog. Note that the original design, as delivered, featured flat-topped side tanks. The curved top is actually a weight added later to assist adhesion.

THE LIGHT RAILWAY ACT

In 1883 the British government passed the Tramways Act for Ireland. This was designed to open up depressed rural areas in the wake of the potato famine and promote growth and repopulation. Promoters of local railway or tram lines could apply to the Grand Juries – the local government organizations – for grants and permission to build lines under this act, which would be underwritten financially by the Grand Juries themselves. Unfortunately there was little or no timescale inserted into these agreements, meaning that the lines could spend many years running without making any profit whatsoever and yet the financial underwriting would continue. This translated in the long term into local taxpayers footing the bill for railways that had not run, and were unlikely to be able to be run, in anything but in a subsidized state. Despite the way that this arrangement turned out, the system was initially thought of as successful and it can be no coincidence that by the 1890s the British Government passed an act for the British mainland with similar aims, although without the heavy subsidies of the Irish system.

The Light Railways Act was passed in 1896 and a commission was set up to oversee the applications and passing of ‘Light Railway Orders’. Initial finance could be made available from the government and the projected line(s) would not need an individual act of parliament, only a ‘Light Railway Order’, thus reducing the cost to the promoter. Most of the lines built under the act were of standard gauge, such as the Rother Valley Railway and the Sheppey Light Railway, but a percentage were built to a narrow gauge. The act set out to provide this streamlined path through railway legislation with certain provisos: lower maximum speeds (often 25 or 15mph), lower axle loadings for rolling stock and reduced signalling and safety standards. In a nutshell: this was a template for a railway that was less likely to cause damage and accidents than the faster, heavier main and branch lines that already existed. This enabled lines to be built with less expense by using lighter construction materials, reduced signalling apparatus, smaller locomotives and without the necessity to build grand station facilities and other expensive infrastructure. This last point produces a definite light railway ‘look’. Although other local building materials, such as stone, were used, the overwhelming architectural style of the light railway age was timber-framed, corrugated iron sheds – a building style more akin to farm architecture than the traditional British railway station.

Golf Links station (originally Camber Sands) on the Rye and Camber Tramway as photographed in the late 1980s. The front of the canopy has been filled in and the structure was being used as a storeroom at the time. Note that the 3-foot gauge track is encased in concrete. This was done to enable road vehicles to use the track bed after closure, first by adding strips on the outside of the rails, and then infilling the centre at a later date. The cars on the left stand on the platform road; the loop line is to their right, and a siding to a short jetty runs to the far right.

Classic light railway architecture – timber-framed with corrugated iron cladding – here at Pen-y-mount on the Welsh Highland Railway. This would make an ideal small generic station building for a narrow gauge model.

This ‘look’ means that it is possible to view the lines built under the act and in this style as, at least visually, a separate group. Although the lines on this point are very blurred, in the main the mineral haulers generally used local building material, often in the form of quarry waste, to construct any buildings on the line. The fact that both light railways and the narrow gauge mineral haulers were mostly initially independent of any standard gauge company involvement meant that each line took on a very individual appearance. For instance, it would be difficult to mistake the buildings of the Welshpool and Llanfair with those of the Tal-y-llyn, The former being mostly corrugated iron, the latter mostly slate waste and timber.

THE FIRST WORLD WAR EFFECT

It took the British authorities some two years to implement a light narrow gauge system during the First World War. By this time the German forces already had systems in place to move munitions to the front by rail. It wasn’t until the British took over a French sector with a 60cm gauge system that the benefits of using a lightly laid narrow gauge railway over rough ground found favour. The 60cm gauge (which was remarkably close to Spooner’s 1ft 11½in) was quickly adopted to match the existing French lines, and the British set to work building a large system totalling over 900 miles (1,480km) of lines serving what was by then an almost static fighting front, and which was usually known as the War Department Light Railway (WDLR).

The problem for the British Authorities was that while freight stock could be manufactured and delivered quickly from British builders such as the Gloucester Railway Wagon and Carriage Company, the British locomotive builders were already working at full production capacity supplying munitions – Hudswell Clark, Hunslet and Barclay combined could produce only 257 locomotives between them. This supply shortfall led the British to approach American builders, who, by having a more intensive production method, were able to fulfil the requirement in a short period of time; the builders Baldwin and Alco (American Locomotive Company) supplied almost 500 side tank locomotives of largely similar 4-6-0 and 2-6-2 designs to be shipped to France.

A 40hp Motor Rail Simplex built for War Department use during the First World War, here in its ‘open’ version without side doors, but with a roof. The other versions were ‘protected’ with doors, and ‘armoured’, fully enclosed. This example was pictured at Amberley Museum.

An Alco (American Locomotive Company) 2-6-2 built for use on the Western Front during the First World War. This example was photographed in the early 1990s under preservation in France.

Baldwin ‘petrol tractor’. This American machine was also built during the First World War and is now preserved in France.

A 20hp Simplex. These small petrol tractors were used in lighter situations than the 40hp machines and were largely built without any protection for the driver.

In addition to these steam locomotives, several hundred ‘petrol tractors’ were built, largely by Motor Rail of Bedford. These internal combustion units were favoured for use close to the front as they produced no glowing fire or smoke that would be easily visible to the German forces, although the loads which could be drawn were much less. Smaller numbers of petrol units were also produced by British Westinghouse and Dick Kerr (both to a similar design) and again from the American Baldwin company.

The Motor Rail units were built with two engine sizes – 20hp and 40hp – and the larger of these designs were progressively fitted with armour in three styles: ‘open’, with armour front and rear; ‘protected’, with the addition of side doors and a canopy roof; and ‘armoured’, which meant fully enclosed. The fully enclosed version, apart from being highly uncomfortable to drive, has developed a certain notoriety and has been colloquially referred to as the ‘Tin Turtle’. In addition to this, when the Americans eventually entered the war in 1917, they too imported locomotives and stock to the battlefields, resulting in a huge amount of equipment lying redundant by the end of the war.

At the end of hostilities in 1918, much of the material and rolling stock was handed to the French, finding its way into agricultural and industrial use, sometimes using the same lines that the Allies had designed to transport munitions. A small amount of stock either remained in Britain or was shipped back across the channel, and by 1919 was gradually offered for sale through the War Stores Surplus Disposal Board. Much of this stock either ended up in industry or was snapped up by narrow gauge railway operators.

The major effect of all this redundant stock and infrastructure was that almost overnight the existing unofficial smaller standard gauge of 3 feet – often used by contractors for temporary lines – changed to 2 feet (or more accurately 60cm). New lines such as the Ashover Light Railway chose 2 feet as the optimum gauge, buying a total of six Baldwin steam locomotives and seventy wagons from the surplus board. Other existing lines were given a new lease of life by the availability of this apparently cheap source of motive power: the Glyn Valley Tramway and the Snailbeach District Railway purchased American locomotives and re-gauged them to 2ft 4in, replacing largely wornout existing stock. This influx of equipment presented the existing (or new) British narrow gauge lines with replacement stock, and a new tried and tested gauge, but more importantly introduced cheap lightweight internal combustion power where only steam had previously existed (unfortunately war surplus also presented the public with cheap lorries and men that could now drive them – men and vehicles that would provide a direct competition to Britain’s rail network). Although it didn’t completely replace steam power, the WDLR ‘petrol tractors’ proved that there was an alternative, one which was enthusiastically received by one man in particular.

Many locomotives built for use on the Western Front found their way into civilian use post 1918. This 20hp Motor Rail ended up at a council sewage works.

COLONEL STEPHENS

Holman Fred Stephens has become legendary among enthusiasts of independent railways. His skills as an engineer would have been enough to set his name into history by being involved in planning many minor lines in England and Wales. However, it was his astute (some might say, reckless) business head in acquiring a group of run-down lines and controlling them all from an office in Kent that will tie Stephens to the idea of the ‘run on a shoestring’ public railway. Stephens engineered and/or managed four narrow gauge lines: the Snailbeach District, the Ffestiniog and Welsh Highland (by then combined); the Ashover Light Railway; and the Rye and Camber Tramway – four lines with little in common either in gauge, traffic or geography. These and Stephens’ standard gauge lines were managed in a style that could only be described as laughable to most professional railway operators and yet they worked. Worked, that is, with run-down rolling stock, poor safety standards and a low-wage economy. The classic example of this was Stephens’ employment of a one-armed man as he was able to do the work required … but naturally at half the price.

All that said, Stephens was highly modern and forward-thinking; we take for granted the internal combustion engine in powering trains now, but Stephens was not only planning the use of such power at the turn of the twentieth century, but actively promoted its use on many of his lines at a time when steam was still considered the only viable option. In addition to that we have Stephens to thank for at least two lines that made it into preservation; it is unlikely that either the standard gauge Kent and East Sussex Railway or the Ffestiniog would have survived to the safety line of the end of the Second World War without Stephens’ management. Stronger lines, such as the Lynton and Barnstaple, failed, being taken over by the Southern Railway (via the LSWR) at the grouping, and promptly shut a little over a decade later in 1935. It’s also worth pondering what would have happened to the Southwold Railway in Suffolk had it fallen under Stephens’ control, rather than closing as it did in the 1930s.

THREE FOOT GAUGE

Three-foot gauge is often seen as the poor relation in British narrow gauge, the above mentioned Southwold Railway being the sole public example of any duration on the UK mainland. The gauge did, however, gain acceptance with road and railway building contractors as it had the benefit of being light and quick to lay as a temporary system, but still being able to carry loads approaching that of standard gauge wagons; if it had not have been for the major push toward 60cm/2-foot gauge during the First World War then the railway gauge of 3 feet may well have had a happier, longer life. Not all was lost, though, for the wider gauge; for once the waters of the Irish Sea are crossed things look up.

Due to the twist of government policy outlined above, there became what were effectively two standard gauges in Ireland: 5ft 3in (which still remains) and, for most of the lines built under the Tramways Act, 3ft gauge. These were by and large a financial disaster; built to open up depressed area, they often had the opposite effect bringing more goods inward than the area exported and allowing the indigenous populations more freedom to leave. Even with the generous government subsidies and later the introduction of internal combustion power, the first closures began in 1924. The interest, particularly for the modeller, is the sheer size of these lines: although there were diminutive locomotives and stock such as tiny Wilkinson enclosed tram locomotives, many of the Irish lines were not far short of standard gauge loading gauges. These were visually a long way from the Spooner-designed slate lines, boasting a spread of sizes up to the Londonderry and Lough Swilly 4-8-0 tender locomotives and 4-8-4 tanks, therefore giving the modeller an entirely different subject matter from the majority of UK narrow gauge railways.

A 3-foot gauge County Donegal railcar pictured at Douglas on the Isle of Man in 1995. Railcars were introduced by the CDR in the post-war years as a cost-saving device, but failed to save the line.

CH Wood, one of the classic 3-foot gauge 2-4-0 ‘Manx Kittens’ built by Beyer Peacock and seen here resting at Port Erin in 1995.

The only place where the 3-foot gauge survives in the British Isles in anything close to its original form is on the Isle of Man. For such a small area the island was for the latter part of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries very well served by a 3-foot gauge system. Beating the introduction of 3-foot gauge in Ireland by only a matter of months, the IOM quickly developed a rail system of independently managed lines along the long southeast coast, across the island and running towards the northern tip as far as Ramsey. The early development of the Manx and Irish 3-foot lines would be hard to separate, and although the definitive reasons for the choice of gauge are lost, it is obvious that there is a strong link. The difference in the histories is that while the Irish lines have gone, a mixture of public money and increased tourism mean that some 50 per cent of the Manx lines survive, albeit in a much slimmer form than in the heyday of the early twentieth century.

For the student or modeller of 3-foot gauge lines, the Isle of Man would be the first place to examine. Whilst these two systems dominated their localities, 3-foot gauge on the UK mainland was much more thinly spread, the Rye and Camber, Ravenglass and Eskdale and the Southwold being the only public lines of note built to the gauge. The R&E quickly fell into difficulty and then re-gauged to 15 inches. The R&C is hard to define as it was termed a ‘tramway’ and was largely built to serve Rye Golf Club, was not strictly a common carrier, and did not require the usual Act of Parliament as it was constructed entirely on private land. Compared to most other 3-foot lines it was small both in route miles and with regard to the rolling stock size and quantity. Only three locomotives were used: two 2-4-0 tank engines supplied by Bagnall, and a Motor Rail petrol tractor.

INDUSTRY

It’s very hard to define what is and what isn’t an industrial narrow gauge railway, as most, if not all, lines were either specifically built to handle a single goods traffic, or developed that way during the life of the line. It could be said that even the common carriers such as the Southwold or the Welshpool lines were industrial if you consider a heavy bias toward farm traffic as industry. Where this definition becomes clearer is with the non-public lines: those tucked away from view, which could be exceptionally large and sprawling such as the various ironstone systems in the English Midlands, or minuscule, down to lines which were measured not in miles but in yards, often operated by just one man and just one or two items of rolling stock.

There were literally hundreds of these small operations all over the UK built to various gauges, but with 2-foot/60cm dominating due to surplus purchases after the First World War. Before dumper trucks became the norm, the first thought when something heavy or dirty needed moving repeatedly was to install a small railway. Hence there was a proliferation of such lines serving sewage works, brickworks, sand pits, quarries and small mining operations, and these were the most likely places to find a narrow gauge railway in the UK. These railway systems could be tiny – a stock of one locomotive and less than half a dozen open wagons was not unusual. The operation of these railways – as viewed from a modelling perspective – could be thought as little short of boring, with a small diesel drawing a few wagons back and forth between two points all day.

Industrial lines were the polar opposite of the glamorous mainline steam railway – often dirty and battered, often with appalling trackwork, usually regarded with distain by serious rail enthusiasts, and with complete lack of interest by those who worked them. They were often simply a rail-run conveyer belt, designed to move a material over a short distance as cheaply and efficiently as possible. Only now do some get enthused about industrial lines. To those who worked with them, these railways were just another piece of expendable industrial plant. If a wagon became unserviceable it was not lovingly repaired, but usually unceremoniously dumped at the nearest convenient trackside location where it would slowly corrode, disintegrate and gradually disappear under a covering of undergrowth, only to be rescued to cannibalize for parts, or if lucky, passed to preservationists on the line’s closure.

Thakeham Tiles locomotive preserved at Amberley in 2013. This tiny 2-foot gauge machine was built at the Thakeham works using an Amstrong Siddeley engine on a redundant Hudson skip chassis.

One of the stalwart types of the industrial 2-foot gauge was this Ruston & Hornsby locomotive.

Many industrial lines of this type were initially steam operated, but this was the area where the early internal combustion engine found its natural home. The constant drive for cheap and efficient power gave diesel, petrol and in certain cases, battery power, the edge with easy maintenance and (compared to a steam locomotive) quick starting. Often the manufacturers of industrial locomotives cited the cheap running cost as a ‘gallons per day’ figure, as once started a locomotive was left to run throughout the working day whether it was actually hauling something or not. Rolling stock was usually simple open tipping wagons, which in early times owed their design more to horse-drawn cart working, being constructed from timber or iron framework with a tipping body built from wood, the axles carried in internal bearings. The size of these wooden wagons varied from something approaching the size of a small standard gauge wagon down to small mine-type tubs or drams that could be pushed by hand.

The most ubiquitous of all of the rolling stock designed for industrial use was the ‘V skip’ tipping wagon. Made in their thousands to several similar designs, they were of rugged metal construction, hardy enough to handle locomotive haulage, but with tipping bodies light and balanced enough to be emptied by one man. Not only were these used as intended, but they were also modified either by the original manufacturer or locally on site into a variety of other rolling stock styles, such as flat wagons (simply by attaching planks to the chassis), fuel or water bowsers, and in some cases even crude passenger-carrying vehicles, by adding bench seating either front/back facing or longitudinally. This quasi-home-made approach gave the industrial narrow gauge rolling stock a quirky individual appearance rarely matched on public passenger-carrying lines or on the standard gauge.

In the later days of 2-foot gauge industrial railways the Hudson Rugga skip reigned supreme. Light enough and balanced well enough to be tipped by one man and extremely robust, they were very popular with many industries to carry heavy, loose loads such as sand, gravel, or waste of various types. This particular skip even has a film credit, being featured in the Bond movie You Only Live Twice.

Hudson skip chassis were adapted to many other uses, either by the maker or on site. Here a simple flat wagon has been built with the addition of a planked floor. Other modifications include tank wagons and even open coaches by further adding bench seats.