0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

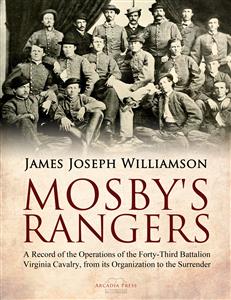

- Herausgeber: Arcadia Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

James J. Williamson was one of Mosby’s Rangers, so this is a memoir as well as the story of Mosby’s command.

While this is in no way an objective account, it’s still a necessary read for anyone who wants to study John S. Mosby and his men. Williamson also provides correspondence and extracts from the Official Records for both sides and contains interesting stories about some very colorful individuals.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

James J. Williamsonof Company A

MOSBY’S RANGERS

A RECORD OF THE OPERATIONSOF THE FORTY-THIRD BATTALIONOF VIRGINIA CAVALRY FROM ITS ORGANIZATION TO THE SURRENDER

Copyright © James J. Williamson

Mosby’s Rangers

(1909)

Arcadia Press 2019

www.arcadiapress.eu

Storewww.arcadiaebookstore.eu

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MOSBY’S RANGERS

PREFACE TO REVISED EDITION

It is my purpose in this Revised Edition to correct errors, supply omissions, and add such new material as I have collected since its first publication In doing this I sought the co-operation of my old comrades, asking them to call my attention to any statements which they found at variance with their knowledge of affairs, or where they may have had better opportunities of learning the facts.

After the close of the war and the disbanding of our command, the survivors scattered over the country, some even seeking refuge beyond the border, so that it was difficult to ascertain the whereabouts of parties to obtain information regarding affairs of which I had but few details. Even when these were found it was sometimes hard to reconcile contrary statements. Two persons, perfectly honest, equally reliable, and either with or without prejudice, will give different versions of the same occurrence, each viewing it from his own standpoint. This is particularly noticeable in recounting the details of a fight, where each one usually has sufficient to demand attention in his own immediate vicinity, and things may take place at a little distance from him, or without his range of vision, unnoticed by him, though plainly seen by others. Aware of this, I have sought to get the statements of others, not only to verify my own, but to add to my account what may have escaped my observation or may be brought to my recollection in this way. The reunions of these later years have brought together the survivors and given an opportunity of picking up many missing links.

There are no doubt many things yet which are not mentioned in this work. I have had comrades say: “You do not speak of a little affair which took place at — (naming time or place).” In the Good Book St. John tells us, there are also many other things which if they were written, every one, the. world itself would not be able to contain the books that should be written. While I would not make such a broad assertion as this, I can safely say that the deeds of Mosby and his Men, if written every one, would fill a much larger volume than the book before you.

While the bulk of the command was on an excursion in the Shenandoah Valley or in Fairfax, small squads would be out in various directions; consequently many occurrences are not noted, and the affair omitted may in some instances strike the participant as being more important than others here given.

In keeping a diary, which was the foundation of this work, I simply followed a habit, which had become an amusement, and at the time I had no thought of publishing. Had I entertained a suspicion of this I would have been more industrious in collecting data of important facts and interesting incidents. I now see with regret where I could have obtained a fund of entertaining matter, which I did not even take pains to inquire into or make note of at the time. So it is with us all, to a greater or less extent — as we grow older we all look back with regret at our lost opportunities.

PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION

The object of this work is to put in durable form a record of the exciting scenes and events in the career of Mosby’s Rangers, in most of which I was an humble actor, and to preserve the memory of the gallant deeds of Colonel Mosby and of his brave companions who shed their blood, and of our heroic dead who gave up their lives, in the cause for which we fought.

It is unnecessary at this late day to vindicate the military career of Mosby, or to justify his taking up arms in obedience to the call of his State. The falsehoods so industriously circulated concerning Mosby’s Men during the excitement of the war by partisan newsmongers, who are often too ready to pander to popular sentiment, without regard to truth, have been forever set at rest by the many Complimentary letters and notices regarding Mosby from Generals Lee, Stuart, Grant and others. — Federal and Confederate.

The main events of the war have long since passed into history, and will now be judged by unprejudiced minds, that will award to all their just measure of commendation or censure.

I have worked with an honest purpose. While I have presented the facts, and have given the best versions I could of matters from my standpoint, I have also deemed it only fair to give the other side of the story, when obtainable, as it is my desire to do justice to all, whether friend or foe.

This book is really the result of the habit of keeping a diary. During my imprisonment in the spring of 1863, in the Old Capitol prison in Washington, I kept a diary as a means of whiling away the tedious hours of prison life. After being exchanged, I joined Mosby in April, 1863, two months before the organization of Company A, his first company, and was with him until the surrender. The habit acquired while in prison still clung to me when I entered upon the active life of a ranger. It then became a pleasure to jot down the events that came under my observation or that I heard related by my comrades or others. I soon began to feel that my work was not completed until I had noted down briefly what had happened during the day. In this way my diary was kept — sometimes written by the wayside, sometimes by the camp-fire, sometimes in the quiet of the fireside. As time went on, my interest in the record increased, though it was kept simply as a matter of habit and amusement — not with any idea of publication.

In after years, realizing that I was growing old, and that my old comrades were dropping off one after another, it occurred to me that the surviving members of the command might be interested in this little diary, if written up and put in suitable form. My first idea, when preparing the manuscript, was to publish it as a magazine article, under the title of “Leaves from the Diary of one of Mosby’s Men.” Then I set about collecting portraits of officers and members of the command, in which I succeeded far beyond my expectations. I also procured from the records of the War Department, Official Federal Reports relating to many matters, in order to give the Federal version. The work grew on my hands.

Meeting my old friend, Ralph B. Kenyon, the publisher, about this time, and telling him what I contemplated, he said that my record supplied too important a chapter of war history to be hidden under such a title and published in such a way, and an arrangement was soon made to print it as a history of Mosby’s Rangers.

Once in hand, no pains or expense have been spared to make the work as complete as possible in all its details, so that it might be not only an accurate and authentic record of the doings of Mosby’s Men, but that for the surviving members it might be a souvenir of the old days. Whether this has been accomplished or not, the book must speak for itself.

I am glad of this opportunity to make grateful acknowledgment to many friends and comrades whose names and portraits appear in these pages, who have assisted me, both in collecting pictures, and in furnishing details where my record was imperfect or fragmentary. Among these I am particularly under obligations to Mr. George S. Ayre, Lieut. W. Ben Palmer, Charles H. Dear, Capt. Walter E. Frankland, John H. Foster, Joseph W. Owen, Lieut. Channing Smith, John N. Ballard, Lieut. Joseph H. Nelson and Zach. F. Jones. I have also drawn heavily on the pictorial collections of James E. Taylor and Charles Hall, who were both in the ranks of the Federal army, but who have since proved my warm friends and earnest helpers — “Enemies in war; in peace, friends.”

Ties of friendship were formed with companions in arms which death alone can sever. It is with mingled emotions of sadness and pleasure that we cast a fond, lingering look back through the misty past, and re-enjoy in some measure many happy hours, which, amid all the hardships and disappointments of those exciting times, appear in the retrospect like green spots in the journey of life.

If this work will refresh the memory of my comrades and thus enable them to live over again some of the old scenes, and at the same time be the means of convincing our Northern brothers that “Mosby’s Men” were not quite so bad as they have been represented to be, the hope of the author will be realized.

J. J. W.

Jersey City, N. J.

CHAPTER I

Why I Joined Mosby — Imprisoned in the Old Capitol at Washington— Sent to the Parole Camp near Petersburg and Exchanged — I set out to find Mosby— My First Sight of Him — Brief Sketch of his Life — Mosby a Prisoner — Promoted to a Captaincy in the C. S. A. — Mosby’s First Detail— Who “Mosby’s Men” Were— How they Lived and How they Fought — Regulars vs. Partisans — Guerrillas and Bushwhackers — Jessie Scouts — Tributes to Mosby and his Men— General Grant’s Opinion of Mosby— Mosby’s Tactics

Early in the spring of 1863, after an imprisonment of some months in the Old Capitol, at Washington, which had been converted into a political prison, the writer was sent, together with a number of others, via Fortress Monroe and City Point, to the Parole Camp at Model Farm Barracks, near Petersburg, where we were detained about two weeks until exchanged.

Among the acquaintances I had made in prison were six young men who, like myself, being denied the privilege of returning to their homes, had determined to unite their fortunes with Captain Mosby, who was then making a reputation by his dashing and successful exploits. The injustice of my imprisonment and the arbitrary and partisan oath offered me as a condition of release, alienated or rather hardened my feelings, so that I readily joined this party, and together we started in search of the daring ranger.

Journeying from Petersburg to Gordonsville by railroad, we proceeded thence on foot through the country to that portion of Virginia occupied by Mosby.

When we reached the little town of Upperville, in Fauquier County, we learned there was to be a meeting of “Mosby’s Men” at that place on the following day. So after a night’s rest and breakfast in the morning, we walked out through the town and saw them coming in from various directions.

Soon I beheld Mosby himself. From the accounts which I had heard and read of him, I expected to see a man such as novelists picture when describing some terrible brigand chief. I was therefore somewhat surprised when one of my companions pointed to a rather slender, but wiry looking young man of medium height, with light hair, keen eyes and pleasant expression, who was restlessly walking up and down the street, and said: “There is Mosby.”

I could scarcely believe that the slight frame before me could be that of the man who had won such military fame by his daring.

John Singleton Mosby was born at Edgemont, Powhatan County, Virginia, December 6, 1833. His father was Alfred D. Mosby, of Amherst County, and his mother, Virginia I., daughter of Rev. Mr. McLaurin, an Episcopal minister. He graduated at the University of Virginia, and began the study of law. After completing his studies he settled in Bristol, a small town on the boundary line of Virginia and Tennessee, where he successfully practiced his profession. He married Miss Pauline Clarke, daughter of Hon. Beverly J. Clarke, of Kentucky, formerly United States Minister to Central America, and at one time a Member of Congress.

At the commencement of the war Mosby was engaged in the practice of law. He entered the army as a private in a cavalry company, the Washington Mounted Rifles, commanded by Capt. William E. Jones (afterwards General Jones). This company was incorporated in the First Regiment Virginia Cavalry, Captain Jones being promoted to the command, and Mosby was appointed Adjutant of the regiment. By the reorganization of the regiment Colonel Jones was thrown out, and consequently his adjutant relieved of duty. Mosby was then chosen by Gen. J. E. B. Stuart as an independent scout.

He was the first to make the circuit of the Federal Army while in front of Richmond, thereby enabling General Stuart to make his celebrated raid around the entire army of General McClellan, on which occasion Mosby went as guide.

Feeling that there was a wide field for the successful career as a partisan which he had mapped out for himself, Mosby urged General Stuart to give him a small detail of men with which to operate until he could enlist a command. While he met with a refusal of this request, he was given a letter recommending him to General Jackson, then in the vicinity of Gordonsville.

It happened that Gen. Rufus King, who was in command of the Federal forces at Fredericksburg at this time, was ordered by General Pope to send out a raiding party for the purpose of destroying as much as possible the Virginia Central Railroad, and so interrupt communication between Richmond and the Valley. Mosby encountered this party near Beaver Dam, was captured by the Second New York Cavalry, “Harris Light,” Col. J. Mansfield Davies, and sent as a prisoner to Washington.

After his release from the Old Capitol, and while on the prison transport awaiting exchange, Mosby saw the transports bringing Burnside’s forces from the South, and learned from conversations on board the prison boat that the troops were destined for Fredericksburg to unite with Pope; then on the Rapidan, and not to reinforce McClellan. As soon as the exchange was effected, Mosby hastened to Richmond and imparted this information to General Lee, who immediately dispatched a courier to General Jackson. The result was the battle of Cedar Mountain.

How well Mosby performed his duty as a scout is shown by the following:

“Special Order No. 82.

“His Excellency the President has pleased to show his appreciation of the good services and many daring exploits of the gallant John S. Mosby by promoting the latter to a captaincy in the Provisional Army of the Confederate States.

“The General commanding is confident that this manifestation of the approbation of his superiors will but serve to incite Captain Mosby to still greater efforts to advance the good of the cause in which we are engaged. He will at once proceed to organize his command as indicated in the letter of instructions this day furnished to him from this Headquarters.

“By command of General R. E. Lee:

“W. W. TAYLOR, A. A. G.”

The winter of 1863, about the time Mosby was budding into notoriety, was a season of remarkable activity for the Confederate cavalry. Their bold and successful raids and daring attacks and surprises had filled the breasts of the young cavaliers with most romantic visions and ardent de sires to enter upon this life of wild adventure. Stuart’s brilliant achievements, General Imboden’s forays in the Shenandoah Valley, Fitzhugh Lee on the Rappahannock, Gen. William E. Jones attack and rout of Milroy’s Cavalry in the Valley, the daring raids of Major E. V. White and his Loudoun Rangers along the Potomac, and the dashes of Captain Randolph, with his famous Black Horse Cavalry, furnished material for stories which read like the deeds of heroes of romance, and charmed the little groups around the firesides of cabin and hall.

At first a few men from the First Regiment Virginia Cavalry were detailed to act with Mosby, but he soon succeeded in obtaining a sufficient number of volunteers, and the detailed men were then, with a few exceptions, sent back to their commands.

“Mosby’s Men,” when not on duty, were mostly scattered through the counties of Loudoun and Fauquier. There were few indeed, even among the poorest mountaineers, who would refuse shelter and food to Mosby’s Rangers.

Having no camps, they made their homes at the farm houses, especially those along the Blue Ridge and Bull Run Mountains. Certain places would be designated at which to meet, but if no time or place had been named at a former meeting, or if necessary to have the command together before a time appointed, couriers were despatched through the country and the men thus notified.

Scouts were out at all times in Fairfax, or along the Potomac, or in the Shenandoah Valley. Whenever an opening was seen for successful operations, couriers were sent from headquarters and in a few hours a number of well-mounted and equipped men were at a prescribed rendezvous ready to surprise a picket, capture a train or attack a camp or body of cavalry. After a raid the men scattered, and to the Federal cavalry in pursuit it was like chasing a Will-o’-the-Wisp.

The command was composed chiefly of young men from Fairfax and the adjoining counties, with some Marylanders, many of whom had been arrested and imprisoned or had suffered injuries and injustice at the hands of the Federal government or the invading army. It was the custom of many Federal officers to retaliate upon defenseless citizens for injuries inflicted upon them by Confederate soldiers, and can any one feel surprised at “Mosby’s Men” taking up arms to protect themselves or to avenge their wrongs?

A large number lived in that portion of Virginia and Maryland where Mosby was operating, and naturally preferred serving with him, as they were kept nearer home and could enjoy the privilege of seeing their families.

There was always a little jealousy existing between the cavalry and infantry, many of whom lost no opportunity of having a thrust at their rivals. Illustrative of this ran the old joke of the day which will be remembered by the survivors of the war:

An old straggling infantryman, trudging wearily on the road, was overtaken by a cavalryman riding briskly along, who called out:

“Hurry up there, old web-foot; the Yankees are coming.”

“Did you see ‘em, Mister?” queried the infantryman.

“Yes; they are coming on right behind us,” replied the trooper.

“Say, Mister, wus your hoss lame, or wus your spurs broke?” retorted the web-foot.

So also the regular cavalry, viewing the comparative freedom of the life of the Partisan Ranger in contrast with the dull routine and more rigid discipline of camp life, sometimes gave vent to their feelings, and half in jest and half in earnest would banter the Rangers, calling them “Carpet Knights” or “Feather-bed Soldiers” — but when a sacrifice was required, the “Carpet Knights” shed their blood and gave up their lives as freely as did the Knights of old in the palmiest days of chivalry.

The sabre was no favorite with Mosby’s men — they looked upon it as an obsolete weapon — and very few carried carbines. In the stillness of the night the clanking of the sabres and the rattle of the carbines striking against the saddles could be heard for a great distance, and would often betray us when moving cautiously in the vicinity of the Federal camps. We sometimes passed between camps but a few hundred yards apart. We would then leave the hard roads where the noise of the horses’ hoofs would attract attention and, marching through the grassy fields, take down bars or fences and pass quietly through. The carbine was for long range shooting. With us the fighting was mostly at close quarters and the revolver was then used with deadly effect.

I well remember on one occasion, when falling back before the Federal advance on the Little River Turnpike, alternately halting and retreating, the monotony varied only by an occasional long range shot, brave, bluff Lieut. Harry Hatcher impatiently exclaimed to a superior officer: “If you are going to fight, fight; and if you are going to run, run; but quit this d—n nonsense.”

Regarding the custom of our Northern brethren, when speaking of “Mosby’s Men,” to use the terms “guerrillas,” “bushwhackers,” “freebooters,” and the like, I will only say that Mosby’s command was regularly organized and mustered into the Confederate service on the same footing with other troops, except that being organized under the Partizan Ranger Law, an act passed by the Confederate Congress, they were allowed the benefit of the law applying to Maritime prizes. All cattle and mules were turned over to the Confederate Government, but horses captured were distributed among the men making the capture. When it is borne in mind that the men had to arm, equip and support themselves, this did not leave a very heavy surplus, as we received but little aid from the government. The “Greenback Raid” was the only one that brought in any great return, and there were only about eighty men who reaped the benefit of it, as the proceeds of a capture went directly to the men making it. The acquisition of arms and accoutrements, or even horses, did not make the men wealthy. Wagons and supplies were destroyed, though of course the men were allowed to appropriate anything they chose before destroying the captured stores.

Mosby was acting under direct orders of General Stuart up to the time of his death, and then under General Lee, and was independent only in the sense that both Lee and Stuart had such confidence in him that they permitted him to act on his own discretion. In fact it would have been folly to hamper him with orders or place him under restrictions when he was so far separated from the main army, and at times so situated that he could with difficulty communicate with his superiors.

It has been charged that “Mosby’s Men” went in the disguise of Federal soldiers. Such was not the case. They never masqueraded in the uniforms of Federals, except that through force of circumstances men at times wore blue overcoats captured by them from Federal cavalry. This was done because they could get no others. The Confederate government did not, or could not at all times provide proper clothing, and our soldiers were compelled to wear these to protect themselves from the cold. Rubber blankets were common to both armies and when one was worn it completely hid the uniform.

The “Jessie Scouts” of the Federal army, however, will be well remembered by the soldiers of both armies. They dressed in the regular Confederate uniform, which they wore for the purpose of deceiving our men.

Dr. Monteiro, in his very entertaining volume of reminiscences of Mosby’s command, says:

“Every man knew that the slightest suspicion of dishonesty or cowardice would consign him at once to the disgrace of expulsion; and although there must have been the usual modicum of human meanness always found in a given number of human beings, I am enabled to say after three years of active field service in the regular army that I have never witnessed amongst eight hundred men and officers more true courage and chivalry, or a higher sense of honor blended with less vice, selfishness and meanness than I found during my official intercourse with the Partisan Battalion.”

To this I will add a tribute, which will certainly be regarded as unprejudiced. In the Life of Gen. Sheridan, on page 314, in speaking of old rosters, the author says:

“But one of the most remarkable of Confederate cavalrymen is never named in these rosters. Yet he held, having won it fairly, the commission of Colonel. John S. Mosby, the partisan leader of Northern Virginia, deserves a place in any reference to the doings and deeds of the Confederate troopers. He deserves it because he is a man of character enough to win the respect of his foe, and since the war closed to have induced General Grant to write of him as follows, after having appointed him Consul to Hong Kong: ‘Since the close of the war I have come to know Mosby personally and somewhat intimately. He is a different man entirely from what I supposed. He is slender, not tall, wiry, and looks as if he could endure any amount of physical exercise. He is able and thoroughly honest and truthful. There were probably but few men in the South who could have commanded successfully a separate detachment in the rear of an opposing army, and so near the borders of hostilities as long as he did without losing his entire command.’ (Grant’s Memoirs, Vol. 11, p. 142.)

“Perhaps nothing will illustrate Mosby’s intelligence as a soldier and the amount he accomplished better than his own statement of the theory upon which he acted as a partisan leader, and the recognition of his services in that capacity which he received from his superiors. Of the first. Colonel Mosby says that he was never a spy, and that his warfare was always such as the laws of war allow. He epitomizes his theory of action as follows: ‘As a line is only as strong as its weakest point, it was necessary for it to be stronger than I was at every point in order to resist my attacks.’

“… To destroy supply trains, to break up the means of conveying intelligence and thus isolating an army from its base, as well as its different corps from each other, to confuse plans by capturing dispatches, are the objects of partisan warfare… The military value of a partisan’s work is not measured by the amount of property destroyed, or the number of men killed or captured, but’ by the number he keeps watching. Every soldier withdrawn from the front to guard the rear of an army is so much taken from its fighting strength.”

After Mosby had attracted attention by his daring achievements, men came from all parts of the country to join him. Officers resigned positions in the regular army and came to Mosby to serve as privates; even the famed armies of the Old World were not without representatives in his ranks. Although a dangerous service, there was a fascination in the life of a Ranger; the changing scenes, the wild adventure, and even the dangers themselves exerted a seductive influence which attracted many to the side of the dashing partisan chief.

An Austrian General speaking of Napoleon I., said indignantly:

“This beardless youth ought to have been beaten over and over again; for whoever saw such tactics? The blockhead knows nothing of the rules of war. To-day he is in our rear, to-morrow in our flank and the next day in our front. Such gross violations of the established principles of war are in sufferable.”

But Napoleon was generally successful. Mosby, disregarding established rules, fought upon a principle which his enemies could neither discover nor guard against. He was in their front, in their rear, on their flank at one place to day, and to-morrow in their camps at a point far distant. By his enemies he was thought to be almost ubiquitous. What he lacked in numbers he compensated for by the celerity of his movements and the boldness of his attacks. He generally fought against odds often great odds; seldom waited to receive a charge, but nearly always sought to make the attack.

A Federal officer whom we captured when Meade’s army followed Lee into Virginia after the battle of Gettysburg, said: “Yesterday I heard our cavalry were chasing you in our front, and who would expect to find you this morning in the very midst of our army?”

CHAPTER II

March, 1863 — Raid on Fairfax Court-House — Captain Walter E. Frankland’s Reminiscences of his early days with Mosby and Account of his Trip to the Camp of the Fifth New York Cavalry with Sergeant Ames (“Big Yankee”) — Colonel Mosby’s Graphic Description of the Raid and Capture of General Stoughton— Report of the Federal Provost Marshal at Fairfax Court-House— General Stuart’s Complimentary Order — Mosby Promoted to the rank of Major

Mosby’s growing fame was greatly increased by the capture of Brigadier-General Stoughton, at Fairfax Court-House, on the night of March 8, 1863. This bold enterprise was effected by Mosby, who penetrated the Federal lines with 29 men and succeeded in bringing off his captures without loss or injury.

The raid on Fairfax Court-House and capture of General Stoughton was accomplished a short time previous to my joining Mosby, but being one of the most important events in the history of our command, I make it a prominent feature.

Capt. Walter E. Frankland has given me the following very interesting narrative, embracing reminiscences of his first days with Mosby, the desertion of Sergeant Ames (“Big Yankee”) and the particulars of his visit to the camp of the Fifth New York Cavalry in company with Ames, which occurred just one week prior to and suggested the capture of General Stoughton:

Captain Walter E. Frankland’s Narrative.

Having served as private in the “Warrenton Rifles,” Co. K, Seventeenth Virginia Infantry, from Sunday, April 21st, 1861, until late in 1862, when I was honorably discharged at Richmond, where I had been on detached duty in the Provost Marshal’s Office several months, I started with a friend, George Whitescarver, to join Col. E. V. White’s Cavalry, then in Loudoun. After spending several weeks among his relatives in Upper Fauquier, Whitescarver and I, about February 10, 1863, were joined at Salem (now Marshall) by Joseph H. Nelson, and at sundown that evening we three drew up at the hospitable home of James H. Hathaway. A little later in the evening a lone horseman, Frank Williams, rode up, and was also welcomed to its cordial entertainment. I little dreamed that the life-ties born at that supper table, where most of us first met, were destined to bind us through scenes of blood and years of strife and peace.

We four — Nelson and Williams mounted, Whitescarver and myself afoot — resolved to go together to Loudoun and fulfill my original purpose, when, for the first time, we were told by Mr. Hathaway of a private scout named Mosby, who had made several successful attacks on the Federal pickets with a detail of fifteen men of Stuart’s Cavalry; and they were to meet the next day at Rector’s X Roads to make another raid. At Mr. Hathaway’s earnest suggestion we concluded to see Mosby the next day before joining White’s command.

We set out after an early breakfast and reached the rendezvous in time to see Mosby, who was then but a private in rank with a dozen men (part of his detail having been captured), but who was destined to prove the most remarkable, indomitable and successful warrior in that line developed by the great Civil War, or known in American history. I was made spokesman, and soon we arranged to join him as his “own men,” being his “first four.”

Frank Williams and Joseph Nelson, having horses of their own, accompanied Mosby on that raid, and as Mosby was to mount Whitescarver and myself from his captures, we secured quarters at the very retired little cottage of a poor widow named Rutter. There we awaited Mosby’s return, but to be disappointed by his failure to bring us horses, so Whitescarver borrowed one and went on the next — the Ox Road — raid, leaving me on February 25th.

Just before they rode off, a Yankee deserter, Sergeant James F. Ames, of the Fifth New York Cavalry (afterwards known as “Big Yankee”), came walking up and wanted to join Mosby. No one gave any credence to his story, but I took him with me to the old widow’s house, where we slept and ate together several days and nights. He impressed me as a true man, assuring me he had deserted on account of the Emancipation Proclamation, which, he said, showed that “the war had become a war for the Negro instead of a war for the Union.”

Mosby’s raid proved futile as to mounting me, for the captures were divided among the participants. Ames had so far gained my confidence that I had arranged with him, and we had prepared our arms to make a trip to his late camp at Germantown to supply ourselves with horses.

The day after Mosby’s return we two started from the old widow’s house, near Rector’s X Roads, February 28th, 1863, for a thirty miles walk to the camp of the Fifth New York Cavalry, at Germanton, about two miles from Fairfax Court House. Before we reached Middleburg a heavy rain was falling and when we turned into the Old Braddock road below Aldie, which we took for privacy, the mud was deep and slippery, like putty. We pushed on, making slow progress, our boots heavy with mud and clothing saturated, and when Saturday night came only half our journey was accomplished, the darkness intense and the rain pouring down. We begged quarters for the night on the roadside several miles from Cub Run, and from there resumed our trip after an early hot breakfast, before day on Sunday morning, March 1st.

Leaving the Old Braddock road we crossed the field and entered the woods in which we soon came to Cub Run on a boom. Every crossing log was gone, so we improvised a raft of fence rails, which the whirling torrent drove to pieces just as it struck the other bank. But it had served our purpose and we were safe and at liberty to pursue our mission. We then took our way leisurely, as we had all day in which to make twelve or fifteen miles, as we wanted twilight to cover our near approach to the camp and caution was necessary lest the Federal scouts or trespassing parties might detect us and defeat our purpose.

We learned from citizens that a raid to capture Mosby was about to be made, and by 7 p. m. when we reached the little pine cliff at the rear of the Fifth New York Camp at Germantown, we found the regiment all astir with preparation. It was Sunday night, March 1st, and we watched their movements from our admirable position. When “taps” sounded all quieted down. The clouds were gone, the moon shone brightly and we could see the sentinel pacing to and fro, guarding the officers’ horses, our object, but the camp was restless and every now and then others, besides the “guard,” could be seen moving about, so we waited for the “dead hour” to come. At midnight the bugle sounded, and the horses were “saddled up,” including the two we had come after.

About two hundred men from the Fifth New York and Eighteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry formed on the Little River turnpike and marched off, commanded by Major Joseph Gilmer of the latter regiment. We waited until the sounds of the cavalry horses died away and then deliberately walked to the middle of the camp and talked freely to the “guard,” who never suspected us, even when we walked into two of the stalls he was guarding, bridled two of the horses, mounted them in his presence, and rode away in a walk.

We hoped to reach Mosby before the raiding party, but stiff mud roads were too much for us, and before we succeeded in rejoining him, Mosby with a few men had surprised the First Vermont in Aldie (after they, the Vermonters, had scared Major Gilmer and his two hundred men into a most disgraceful retreat of ten miles) capturing Captain Huntoon, 19 men and 23 horses.

Thus, after vainly waiting about two weeks for Mosby to mount me— the captured horses each time being only sufficient for the men who were on the raids — I had, accompanied and guided by Ames, penetrated the Federal lines to the camp of the Fifth New York Cavalry at Germantown, within two miles of Fairfax Court House, walking thirty miles to accomplish it, in order to mount myself. The success of this enterprise demonstrated the feasibility of passing in between their camps, evading their pickets and far within their lines quietly executing a purpose without causing an alarm.

Mosby’s quick perception turned this to good account by arranging at once to strike deep for some great achievement, and just one week after my success of Sunday, March 1st, Mosby, with twenty-nine of us, on Sunday, March 8th, undertook and successfully executed an enterprise which made him and his command renowned, and brought to his standard hundreds of brave spirits who possessed the very metal he needed to build with, and who were in every way worthy of their illustrious leader. It was the capture of General Stoughton.

The best account of the raid and capture of General Stoughton obtainable is the following article, from the able pen of Mosby himself, as published in the Belford Magazine in 1892:

One of My War Adventures.

About February 1st, 1863, I began operating on the outposts of the troops belonging to the defense of Washington that were stationed in Fairfax and Loudon counties, Virginia. I had with me a detachment of fifteen men from the First Virginia Cavalry, which Stuart had allowed to go with me while his cavalry corps was in winter quarters. As I had camped several months in Fairfax the year before, and done picket duty along the Potomac, I had acquired considerable local knowledge of the country. By questioning the prisoners I took, separately and apart from each other, I had learned the location of the camps and the headquarters of the principal officers. I had been meditating a raid on Fairfax Court House, where I knew there were many rich prizes, when fortunately Ames, a deserter from the Fifth New York Cavalry, came to my command and supplied all the missing links in the chain of evidence. Whenever we made any captures the prisoners were sent under guard to Culpeper. Court House, where Fitz Lee was stationed with a brigade of cavalry. Stuart was then in the vicinity of Fredericksburg. I have heretofore related the affair with Major Gilmer and the First Vermont Cavalry, which occurred on March 2d. As it was necessary to make a detail from the men serving with me to guard the prisoners that were sent to Culpeper, I had to wait several days for them to return before undertaking another enterprise. Gilmer’s expedition into our territory had been so disastrous that the Union cavalry seemed to be content to stay in camp and let us alone. On the afternoon of March 8th, the anniversary of the day that my regiment (First Virginia Cavalry) had the year before crossed Bull Run as the rear guard covering the retirement of Johnson’s army to Richmond, twenty-nine men met me at Aldie, in Loudon county, the appointed rendezvous. My recollection of events is refreshed by my report to Stuart, written three days afterwards, which is printed in the official records by the Government. I did not communicate my purpose of making a raid on the headquarters of the commanding general at Fairfax Court House to any of the men except Ames, and not to him until we started.

The men thought we were simply going down to make an attack on a picket post. It was late in the afternoon when we left Aldie. There was a melting snow on the ground with a drizzling rain. All this favored my plan, the darkness concealed us, and the horses treading on the soft snow made very little noise. We started down the Little River turnpike which runs by Fairfax Court House to Alexandria. From Fairfax Court House another turnpike runs easterly by Centreville, seven miles distant to Warrenton. At Centreville there was a brigade of infantry with artillery and cavalry. This was the extreme out-post. From Centreville there was a chain of outposts extending in one direction, by Fryingpan, to the Potomac; and to Union Mills and Fairfax Station in the other. Near the junction of the two turnpikes, a mile east of Fairfax Court House, there was a brigade of cavalry in camp; the railroad from Union Mills to Alexandria was strongly guarded.

At Chantilly, on the Little River pike, there was also a strong cavalry out-post. The two turnpikes that connected near Fairfax Court House and the picket line from Centrevilla to Fryingpan thus formed a triangle. I found out where there was a gap in the picket line between the two turnpikes and determined to penetrate it. I knew that if we succeeded in passing the outer line without alarming the pickets we might reach the generals’ headquarters at the court house in comparative safety, as we would be mistaken for their own troops even if the enemy discovered us. The headquarters were so thoroughly girdled with troops that no one dreamed of the possibility of an enemy approaching them. In justice to Stoughton, the commanding general, I must say that he had called the attention of the out-post commander to the weak point in his picket line. But no attention was paid to it. He did not conceive that any one had the audacity to pass his pickets and ride into his camps. The commander of the Union cavalry at that time was Colonel Percy Wyndham, an English adventurer, who, it was said, had served with Garibaldi. He had been greatly exasperated by my midnight forays on his out-posts and mortified at his own unsuccessful attempts at reprisal. In consequence he had sent me many insulting messages. I thought I would put a stop to his talk by gobbling him up in bed and sending him off to Richmond. Ashby had captured him in the Shenandoah Valley the year before. When we got to within three miles of Chantilly we turned off to the right from the turnpike, and passed unobserved through the picket line about midway between that place and Centreville and reached the Warrenton turnpike about halfway between Centreville and the court house. I was riding by the side of one of my men named Hunter, and at this point I told him where we were going. He realized, as I did, the difficulties and dangers that surrounded us. I told him our safety was in the audacity of the enterprise. We were then four miles inside the enemy’s line and within a mile or two of the cavalry companies. We could no doubt have marched straight into them, or challenge and brought off a lot of men and horses. But I was hunting that night for bigger game, and knew that Wyndham did not sleep in the cavalry camp, but at the court house a mile beyond. I also knew that General Stoughton’s headquarters were there. To a man uninitiated into the mysteries of war our situation, environed on all sides by hostile troops, would have appeared desperate. To me it did not seem at all so, as my experience enabled me to measure the danger. Proceeding a short distance on the pike towards the court house, we turned oil to the right, flanked the corps directly in front of us, and came into the town unmolested at two o’clock in the morning. It had been my intention to get there about midnight, but our column got broken in two at one time in the darkness; the rear portion remained standing still for some time, thinking the whole column had halted. We had gone a considerable distance before it was discovered. So I had to turn back in search of the missing. The rear, after standing still some time, moved on, but could not find our trail. They were on the point of going back when by accident we came upon them wandering in the dark like Iris in search of the lost Osiris. This involved considerable delay. With the exception of a few drowsy sentinels all the troops in the town were asleep. Nothing of the kind had ever been attempted before during the war, and no preparations had been made to guard against it. It is only practicable to guard against what is probable, and in war, as everything else, a great deal must be left to chance. Once inside the enemy’s lines everything we discovered as easy as falling off a log. There was not the slightest show of resistance. As the night was pitch dark it was impossible to tell from our appearance to which side we belonged, although all of us were dressed in Confederate gray.

The names of all the cavalry regiments stationed there were familiar to us; so whenever a sentinel halted us the answer was: “Fifth New York Cavalry,” and it was all right. Of course we took the sentinel with us. All of my men except Hunter and Ames were as much surprised as the enemies were when they found themselves in a town filled with Union troops and stores. As I had never led them into a place from which I was not able to take them out, there was not a faint heart among them. All seemed to have a blind confidence in my destiny. Hunter was at the time a sergeant in the company to which he belonged. I explained the situation to him as we were riding along, as I looked to him more than to any of the men to aid me in accomplishing my design. He showed great coolness and courage, and fully merited the promotion he soon afterwards received. He is now a citizen of California. I had only twenty-nine men — we were surrounded by hostile thousands. Ames, who also knew to what point he was piloting us, rode by my side. Without being able to give any satisfactory reason for it, I felt an instinctive trust in his fidelity, which he never betrayed. When we reached the courthouse square, which was appointed as a rendezvous, the men were detailed in squads; some were sent to the stables to collect the fine horses that I knew were there, others to the different headquarters, where the officers were quartered. We were more anxious to capture Wyndham than any other.

There was a hospital on the main street in a building which had been a hotel. In front of it a sentry was walking. The first thing I did was to send Ames and Frankland to relieve him from duty and to prevent any of the occupants from giving the alarm. Ames whispered gently into his ear to keep quiet — that he was a prisoner. A six-shooter has great persuasive powers. I went directly with the larger portion of the command to the house of a citizen named Murray, which I had been told was Wyndham’s headquarters. This was not so. He told us that they were at Judge Thomas’ house, which we had passed in the other end of the town. So we quickly returned to the court-house square. Ames was sent with a party to Wyndham’s headquarters. Two of his staff were found there asleep, but the bird we were trying to catch had flown — Wyndham had gone down to Washington that evening by the railroad. My men indemnified themselves to some extent for the loss by appropriating his fine wardrobe and several splendid horses that they found in the stables.

The irony of fortune made Ames the captor of his own captain. He was Captain Barker, Fifth New York Cavalry, detailed as Assistant Adjutant General. Ames treated his former commander with the greatest civility, and seemed to feel his great pride in introducing him to me. Joe Nelson saw a tent in the courtyard; he went in and took the telegraph operator who was sleeping there We had already cut the wires before we came into the town to prevent communication with Centreville. Joe had also caught a soldier who told him that he was one of the guard at General Stoughton’s headquarters. This was the reason I did not go with Ames after Wyndham. I took five or six men with me to go after Stoughton. I remember the names of Joe Nelson, Hunter, Whitescarver, Welt Hatcher and Frank Williams. Stoughton was occupying a brick house on the outskirts of the village belonging to Dr. Gunnell.

When we reached it all dismounted and I gave a loud knock on the front door. A head bobbed out from an upper window and inquired who was there. My answer was, “Fifth New York Cavalry with a dispatch for General Stoughton.” Footsteps were soon heard tripping down stairs and the door opened. A man stood before me with nothing on but his shirt and drawers. I immediately seized hold of his shirt-collar, and whispered in his ear who I was, and ordered him to lead me to the general’s room. He was Lieutenant Prentiss of the staff. We went straight upstairs where Stoughton was, leaving Welt Hatcher and George Whitescarver behind to guard the horses. When a light was struck we saw lying on the bed before us the man of war. He was buried in deep sleep, and seemed to be dreaming in all the fancied security of the Turk on the night when Marco Bozzarris with his band burst on his camp from the forest shades:

“In dreams, through court and camp, he bore

The trophies of a conqueror.”

There were signs in the room of having been revelry in the house that night. Some uncorked champagne bottles furnished an explanation of the general’s deep sleep. He had been entertaining a number of ladies from Washington in a style becoming a commanding general. The revelers had retired to rest just before our arrival with no suspicion of the danger that was hovering over them. The ladies had gone to spend the night at a citizen’s house; loud and long I have been told were the lamentations next morning when they heard of the mishap that had befallen the gallant young general. He had been caught asleep, ingloriously in bed, and spirited off without even bidding them good bye. As the general was not awakened by the noise we made in entering the room, I walked up to his bed and pulled off the covering. But even this did not arouse him. He was turned over on his side snoring like one of the seven sleepers. With such environments I could not afford to await his convenience or to stand on ceremony. So I just pulled up his shirt and gave him a spank. Its effect was electric. The brigadier rose from his pillow and in an authoritative tone inquired the meaning of this rude intrusion, He had not realized that we were not some of his staff. I leaned over and said to him: “General, did you ever hear of Mosby?” “Yes,” he quickly answered, “have you caught him?” “No,” I said, “I am Mosby— he has caught you.” In order to deprive him of all hope I told him that Stuart’s Cavalry held the town and that General Jackson was at Centreville.