9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Orford Ness was so secret a place that most people have never even heard of it. The role it played in inventing and testing weapons over the course of the twentieth century was far more significant and much longer than that of Bletchley Park. Nestled on a remote part of the Suffolk coast, Orford Ness operated for over eighty years as a highly classified research and testing site for the British military, the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment and, at one point, even the US Department of Defence. The work conducted here by some of the greatest 'boffins' of past generations played a crucial role in winning the three great wars of the twentieth century: the First, Second and the Cold. Hosting dangerous early night-flying and parachute testing during the First World War, the ingenious radar trials by Watson Watt and his team in the 1930s, through to the testing of nuclear bombs and the top-secret UK-US COBRA MIST project, the 'Ness' has been at the forefront of military technology from 1913 to the 1990s. Now a unique National Trust property and National Nature Reserve, its secrets have remained buried until recently. This book reveals an incredible history, rich with ingenuity, intrigue and typical British inventiveness.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

MOST SECRET

The Hidden History of

ORFORD NESS

‘[Orford Ness] is a wonderful place. It fully deserves a serious analysis of the important role that it has played in Britain’s defence in the past. Your admirable book provides just that ... a real pleasure to read.’

Nick Gurr, Director of Media and Communications,

Ministry of Defence

‘...Symbolic of the conflicts of man and nature, and of nation with nation...’ ‘Orfordness will always be an uncomfortable and untidy place to visit.’

Libby Purves, The Times

‘Walking on Orfordness is probably the nearest you can come in England to walking in the desert.’

Christopher Somerville, Sunday Telegraph

‘The pagodas are now stark monuments to the futilities of the Cold War.’

Merlin Waterson,

retired National Trust Regional Director for East Anglia

‘Orford Ness: eerily beautiful and historically significant –a fascinating trip through recent industrial/military archaeology.’

Sir John Tusa,

former Director-General of BBC World Service

‘...a stretch of coast that reverberates to the music of Benjamin Britten.’

Sir John Quicke,

former member of the Council of the National Trust

For a million years one life simply turns into the next... But a new thought arrives and the island is invaded - a radio mast stands up and starts cleaning its whiskers, afield of mirrors learns to see clear beyond the Alps, a set of ordinary headphones discovers the gift of tongues: there is no reason why any of this should change.

Extract from Orford Ness

by Sir Andrew Motion, former Poet Laureate

‘We are not talking groomed lawns and stately homes here, but a serious and desolate landscape dotted with sinister buildings... Without the work that went on here Britain’s nuclear bomb might never have been.’

Paul Heiney, BBC Radio 4 broadcast

MOST SECRET

The Hidden History of

ORFORD NESS

Paddy Heazell

For the which people of Orford and its Museum keeps alive the story of the place

The National Trust at Orford Ness would be interested to hear from anyone with memories, photographs, documents or other material relating to its ‘hidden’ history. Please get in touch via www.nationaltrust.org.uk

Disclaimer: All reasonable efforts have been made to trace the copyright holders and correctly credit any text quoted herein and any images reproduced. If any material has been used in error, please do not hesitate to contact The History Press for further details.

First published 2010

Reprinted 2010 (twice), 2012

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

Text © The National Trust, 2010

Foreword © Dick Strawbridge, 2010

pp.237-238 © Heather Hanbury Brown, 1995

The right of Paddy Heazell to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7424 3

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7423 6

Original typesetting by The History Press

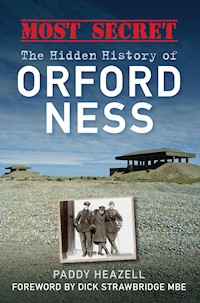

Front cover: Shingle leads up to the pagodas at Orford Ness, © NTPL/Joe Cornish. Inset: The three aviation pioneers: Charles Fairburn, George McKerrow, Bennett Melvill Jones. (Goldsworthy Collection). Back cover: Please see Plate Section for details.

Contents

National Trust Site Map

Foreword

Author’s Note & Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Setting the Scene

Orford Background

Visitors’ Voices

Chapter 2

The First World War and the RFC comes to the Ness

Three Great Men of the Ness

Chapter 3

Wartime Pioneers

The Holder Contribution

The Zeppelin Menace

Night Flying

Hitting the target

Chapter 4

Widening Horizons: RFC to RAF

The Butley Outstation

Auxiliary Forces

McKerrow’s Contribution

The Orford Ness Railway

To Care and Maintenance

Chapter 5

Inter-War Years

Trials Resume

First of the Beams

‘The Bomber Will Always Get Through’

Scientists Take Over

Radar Wins the Argument

The Watson Watt Legacy

Chapter 6

Pre-War Research

The Science of Bombing

Air Gunnery

Preparing for War

Chapter 7

The Research Station at War

The Shingle Street Myth

The Battle comes to Suffolk

Lethality, Vulnerability and Ballistics

Off Duty on the Ness

Chapter 8

The Ness Post-War

RAF Orford Ness?

Bomb Ballistics and Firing Trials

Rockets

The Great Flood

Spark-Photography Research

Chapter 9

Atom Bombs Over Suffolk

AWRE Turns Suffolk Nuclear

The WE177 Atomic Bomb

Hard Target Testing

AWRE Boffins’ Tales

Commercial Testing

Security

Station Secretary

Chapter 10

Cobra Mist: Over the Horizon Radar

Transport Solutions

Progress Slows

Lost in the Mist

An Unexplained Ring

The Plugs are Pulled

Chapter 11

Orford Mess

What to do with the Ness

The Nuclear Might-Have-Been

Over to ‘Auntie’

The Rendlesham UFO

Scrap and Demolition

Chapter 12

The Military Departs

The National Trust Acquisition

Open to the Public

Chapter 13

Epilogue

Glossary

Endnotes

Orford Ness Visitor Map. Note the shingle beach, where the bombing range was once located and the distant Cobra Mist site. It is also easy to appreciate how cut-off this experimental station was from the real world, no wonder the local inhabitants nicknamed it the ‘Island’, it would have been even more appropriate to call it ‘Boffin Island’, as it became in its heyday. (© The National Trust/Orford Ness)

Foreword

Orford Ness is just the right place for keeping secrets; the stories of Bletchley Park and Bawdsey Manor have been told, but Orford Ness has held out.

For centuries it was mainly known for its hazardous shore and to some it is only a desolate piece of land, barely above sea level, that is exposed to bitter easterly winds. However, the War Office’s procurement of the Ness as the home for an experimental establishment, in early 1914, was the start of a period that shaped Britain’s military capability throughout the twentieth century. This book provides a long overdue look at how the top secret trials and experiments that took place in this remote part of East Anglia played a key role in the three great conflicts of the modern age: the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War.

Paddy Heazell brings the story of Orford Ness to life, in this the first book on this subject to be written since the secret and inaccessible military property was opened to the public by the National Trust in 1995. Fifteen years of association with this very special place, ten of which involved painstakingly digging through archives and hunting down those who worked there, have allowed Paddy to piece together the jigsaw so we now get a full picture of what really went on. His investigations, and obvious respect for those who have lived and worked on the Ness, have produced a compelling book in which every chapter makes you swell with pride at the achievement of our forebears.

The figures that have shaped the activities at Orford Ness have been a heady mixture of notable academics, high achievers and, in many cases, extremely brave men. The anecdotes, lots of which come from the first hand accounts of those involved, are frightfully British. Some of the names will be familiar, but there are a lot whose exploits have not previously been written about and their stories would remain untold but for this book.

The detail here is enthralling and it is a very rich story indeed where some of the main players provide links to the birth of radar, vulnerability of gas turbine engines, earthquake bombs and even post-Project Manhattan tests of the ballistics of early nuclear weapons. I remember years ago watching archive films of early radar trials that were being carried out by very English gentlemen, wearing tweeds and smoking their pipes, and marvelling at how business was conducted in the inter-war years. Here, such trials are put into context and allow an appreciation of what our ‘boffins’ were really up to. Interestingly, today we all have our own image of what a ‘boffin’ is, but it was in relation to the pioneering activities that took place on the Ness that the term was coined during the Second World War. It was really one of appreciation, as a boffin was a scientist or technician, who could liaise with the military to understand service requirements and who, not only had the skill and imagination to create wonderful gadgets, but also, had the energy and drive to build them. Far from the pejorative way the word is used today!

There are so many stories about the projects conducted at Orford Ness; every page brings more facts and information about the men who worked there. That said, it was not all glamour and you get a real sense that there was a lot of hard work conducted which would have been mundane, repetitive and even fruitless. However, it is worth noting that the effects of what was learnt at Orford Ness have had long term impacts, for example, work in the later stages of the First World War to determine how to bomb and destroy railways provided lessons applied 65 years later when a Vulcan bomber bombed Port Stanley airfield during the Falklands conflict, and without some of the significant work on aerodynamics, influenced by time on the Ness, we may have been too late to gain sufficient expertise to design the Spitfires and Hurricanes that were so vital for the Battle of Britain.

The teams who have worked at Orford Ness have been a mix of academics, engineers, military men and support staff. They have made an outstanding contribution to the winning of war and keeping Britain safe. The test pilots who lived and worked on Orford Ness were the elite of their profession; we can only marvel at the bravery of the test pilot who took off for the first time on a towed, floating platform only 21 feet wide and 48 feet long. There was undoubtedly a true daredevil spirit among the men and women of the Ness.

This book is ultimately a celebration of real people doing amazing things. It is also a timely reminder that we should never forget those splendid boffins, who alongside our soldiers, have devoted, and often sacrificed, their lives over the years without seeking glory or reward.

Dick Strawbridge, 2010

Author’s Note and Acknowledgements

I first visited Orford Ness as a newly recruited National Trust volunteer in June 1995. There were four full-time staff wardens working on the property at this stage, busily occupied with the land management necessary to turn a military site into a nature reserve while also dealing with the demolition and tidying essential for making the property safe for visitors. The latter tasks were placed in the hands of the dozen or so somewhat bemused volunteers, whose understanding of what on earth Orford Ness was all about was often rather nebulous. The staff had little time to brief us. Excited visitors, fascinated by this hitherto secret place, bombarded us with a host of questions we could not easily deal with. It was sometimes tempting to make up our answers. How misled some of those early visitors were. It was in this context that I decided to exercise the skills I had acquired reading history at Cambridge. I began to find out just what had gone on in this secret site. This book is the product of ten years of mounting curiosity that led to five further years of more directed research.

Two issues of nomenclature. In referring to the place, I have been faced by a question of consistency. It is often referred to as the Ness (meaning ‘nose’ that sticks out into the sea), or even, by locals, as the island (which it isn’t, yet). It can be written as a single word: Orfordness. Throughout this book however, I have adopted the convention of the formal geographical title ‘Orford Ness’ in two words.

One other word I have felt free to use throughout the book is ‘boffin’. To call anyone before the Second World War a ‘boffin’ is incorrect. As I reveal, the word sprang out of work begun at Orford Ness and was coined only after 1940. Yet it has become so much part of our language that it seems perfectly reasonable to retrospectively describe the scientist/airmen of earlier decades, especially as they were so clearly doing exactly what boffins were famed for doing. The first boffin was a former Ness man. Indeed, Orford Ness might well have been renamed Boffin Island.

My research has stemmed from three chief sources. From the time of acquisition in 1993, the National Trust, with commendable foresight, began to assemble a comprehensive archive of material and pictures at their East of England Regional Office, now at Westley Bottom, near Bury St Edmunds. The second main source of information has been the National Archives (Public Record Office) at Kew. The third source has been the only other study of the place: Orford Ness: Secret Site by Gordon Kinsey, which was locally published in 1981. Kinsey of course was gravely handicapped in his enterprise. The Ness was still a secret and inaccessible military property. He could never visit it at the time of writing. Most files in the National Archives were similarly unavailable to him. However, he was able to contact a number of people who had served on the Ness and his work in identifying whatever was then in the public domain has provided an invaluable starting point for my rather fuller account of events between 1913 and 1993. I have ‘borrowed’ much from Kinsey and do so with his permission and blessing.

Is there any call for a history of Orford Ness? Apart from satisfying inevitable curiosity that stems from anything that has the magic word ‘secret’ attached to it, surely the nation owes a debt to those who served it in unpublicised – and in this case, largely unpublished – ways. For three quarters of a century, work was done on the Ness of real importance. The stories of Bletchley Park and Bawdsey Manor have been told. Now it’s Orford Ness’s turn.

A history of Orford Ness can be justified on three basic grounds. The very nature of its existence makes it a geographical phenomenon of real importance. The string of extraordinary military research projects it hosted only adds to its significance. This in turn has made it a place of unique atmosphere. It has a rare beauty, whatever the weather. Few people that visit it are unaffected by its wildness which only enhances the sense that history was made there.

Much background material has been culled from various published works. In some cases and where appropriate, these sources are quoted in the text, either as authorities and or as participants in the events described. I make no apology for including no bibliography, but I can assure the reader that I have authority for every fact quoted. If I have been in doubt, I have said so (as for example, in the role of Barnes Wallis’s alleged visit and trials on the Ness). Though hidden away in remote East Suffolk, much that happened in secret on the Ness was most relevant to contemporary world events. Conclusions I have drawn as to their significance are based on informed judgements, for which I alone am responsible. Inter-war pacifism and consequent subterfuge is a case in point.

I regard this as a general historical study. Coverage of events and activities is representative rather than comprehensive. Moreover it is designed very much for the non-specialist reader. I have managed to discover much (though not all) about what happened on Orford Ness, when, and in most cases, why. I am not a technical expert, however, and the reader needing to discover the details of how weapons work is recommended to look elsewhere. I am of the generation that finds the science involved totally mystifying and have made little attempt to search this out for myself.

The National Archives holds many files relating to work done on the Ness. I am grateful to staff for pulling out many dozens of them over the course of a number of visits to Kew. Not far short of twenty sections have yielded information on the Ness, especially sections AIR and AVIA.

The following libraries and similar institutions proved most helpful:

The Imperial War Museum, London

The National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

The Cambridge University Library

The Orford Museum The RAF Air Historical Branch

The RAF Museum, Hendon

The Radar Museum, Neatishead, Norfolk

The Royal Aeronautical Society Library

The Suffolk Wildlife Trust

The Suffolk County Library and Record Office services

The National Trust has created an audio archive and I record my indebtedness to the work of a volunteer, Roger Barrett, who assembled a significant collection of taped interviews. These have provided useful information and in some acknowledged instances, material which I have been able to quote verbatim.

I record with just as much gratitude the following (and many others doubtless omitted), who have given me first-hand information or pointed me in the right direction to discover it.

Jane Allen, John Anderson, John Backhouse, Len Beavis, Pat Bishop, Brian Boulton, Gordon Bruce, Brenda Carter, Maggie Cooper, Ken Daykin, D.F. Farrant, Chris Fisher, Lord Freeman, Vicky Gunnell, Charles Haynes, Harry Holmes, Chris Howard, Prof. Sir Bernard Lovell, Dennis Knights-Branch, Prof. Geoffrey Melvill Jones, David Miller, Iain Murray, Valerie Potter, Dr Ernest Putley, Brian Riddle, Clive Richards, Peter Rix, Bill Roberts, Ron Richardson, Keith Seaman, Margaret Shepherd, Bert Smith, Prof. Ramsay Spearman, Mary Stopes-Roe, Frank Tanner, Alistair Taylor, Geoffrey Taylor, Jane Timmins, Geoff Twibell, Adrian Underwood and Mike Vincent.

This project would have been out of the question but for the National Trust, which in its generous wisdom agreed to undertake its production. The Orford Ness wardens have been brilliant: Duncan Kent, Dave Cormack and Countryside Manager, Grant Lohoar. No less encouraging and helpful have been the Regional Director, Peter Griffiths and Archaeologist, Angus Wainwright. The Publishing Manager, Grant Berry at Heelis, Swindon and his counterpart at The History Press, Jo de Vries, have undertaken a mammoth task in making sense of the mess I submitted for publication and for the vital tasks of editing and proofreading. For errors of fact or interpretation however, I am entirely to blame. A final word of thanks to a long-suffering family which has tolerated my interminable preoccupation with this story and the monopoly I seemed to assume over the family computer.

I fully recognise that the story of Orford Ness and with it, the revelation of its many secrets, is far from complete. Indeed, I am hoping that this book will provoke the unearthing of much more that I have failed to discover. The National Trust at Orford Ness will most warmly welcome further information, pictures and artefacts relating to this remarkable place. Contact should be made direct to the property, via: www.nationaltrust.org.uk.

1

Setting the Scene

As a place for keeping things secret, Orford is a good choice, for it is unexpectedly remote. In many respects, its contact with the rest of the world has relied on water as much as land. East Suffolk itself can seem very much off any beaten track with its relatively sparse rural population. Between Felixstowe to the south and Lowestoft on the Norfolk border lies some 40 miles of Suffolk’s Heritage Coast, today an almost unbroken nature reserve. With no coastal road to link the intervening towns and villages, it remains a remarkably unspoilt and undeveloped corner of England.

There is only one classified road to Orford. The B1084 takes a distinctly circuitous route from Woodbridge, 10 miles to the west. This road ends uncompromisingly at a riverside quay. For quite a small place, it is quite a big quay. Its very size provides a real clue as to Orford’s importance, particularly during nearly eighty years of military occupation of what locals often refer to as ‘the island’, the extensive stretch of marsh and shingle on the far side of the river Ore. Moreover, there is no way to continue on from Orford, except by boat. This so-called island is in fact a peninsula, narrowly and somewhat precariously attached to the Suffolk mainland at Slaughden, just to the south of Aldeburgh, some 6 miles, as the gull flies, to the north. This is Orford Ness.

There are good reasons for giving the means of communication with the outside world a prominent place in this history. Twisting roads and narrow lanes have always been an endearing feature of this part of the county. The railway from Ipswich to Lowestoft to the north passed 9 miles distant from Orford. Communications – or rather, the lack of them – have inevitably shaped the development of the village. Even the major trunk road to this part of the county, the A12, was only modernised years after secret operations on the Ness were over. Between 1915 and the early 1970s, enormous volumes of traffic, some of it very heavy, made its way along this inadequate route. That such considerable and complex projects were contemplated at such an inaccessible place is not the least of the mysteries of the Ness.

ORFORD BACKGROUND

Orford does not appear by name in the Domesday Book, and hence cannot claim quite the ancestry of some of its neighbours, like Snape or Iken or Sutton. It was no more than the coastal outlet for Sudbourne, now no more than a scattered village, but then a substantial and great estate, 2 miles inland. With a small but secure harbour, then much more open to access from the sea, Orford was a very suitable spot for Henry II to establish a base for exerting royal control. The castle was built to deal with various challenges to the King’s rule, including possible threats from the exiled Thomas à Becket, as well as troublesome sons and rapacious local baronage, led in this district by Hugh Bigod of the nearby Framlingham Castle. Though Henry never visited Orford himself, his garrison must have stabilised the state of East Anglia and it certainly turned Orford itself from an insignificant fishing village into what was for a period, a notable town.

The power and dignity of Orford reached an early zenith in the reign of Elizabeth I, but even then, there were the first clear signs of impending decline. During the later medieval period, Orford had gained a charter entitling it to send two members to Parliament, a right that, disregarding the years of the Protectorate, only ended with the Reform Bill of 1832. The town’s powers were extended by a series of Royal Charters, which gave it land and privileges.

Trade was under pressure, not least because of the shifting shingle spit, which increasingly blocked the harbour entrance. By the early eighteenth century, Orford came to be described by a noted visitor, Daniel Defoe, as ‘once a good town, but now decayed’. Poverty and corruption marched hand in hand, making Orford a classic eighteenth-century rotten borough.

During the eighteenth century, the Seymour-Conway family acquired and developed the estate of Sudbourne Hall. With their title of Earls of Hertford their principal seat was in Warwickshire, at Ragley Hall. They added the manors of Iken and Gedgrave to their existing Suffolk estate, which included Orford village, the castle and the very quay on which all local trade relied. In 1793, the then Earl was created 1st Marquess of Hertford. The Sudbourne estate was attractive for much more than just its game sport. With the ownership of Orford came the lucrative patronage provided by its two parliamentary seats. The Hall was developed by the great architect James Wyatt and became notable for its art collection. The 4th Marquess was succeeded by his illegitimate son, Sir Richard Wallace, who sold the estate in 1884. The family treasures were transferred to their London house, now famed as the Wallace Collection.

Orford had benefited greatly by the generosity of the Hertford family, who built both the school and the Town Hall. With no railway and poor roads, the community was cut off from the rest of the county and was pretty self-reliant. Under its new owners, the Clarks, the estate was to give Orford another thirty years of relative prosperity. However, come the First World War, Orford was indeed fortunate that a new source of patronage appeared: the War Office.

Apart from the castle keep, another tower dominates the Orford skyline. This belongs to St Bartholomew’s Church, which stands rather massively above the road that zigzags past it. Orford’s church was originally no more than a chapel, the daughter church to Sudbourne, some 3 miles away. However, in 1295, with wealth rapidly increasing in the place, an Augustinian Friary was founded and the church in Orford expanded accordingly. Not all of its imposing structure has survived, and today little more than half of the original building remains. It is blessed by fine acoustics making it a favoured location for concerts and was chosen by Benjamin Britten for the première of Noye’s Fludde and his church parable operas.

Shortly before the only road enters Orford, it passes the edge of Sudbourne Park. The Hall, once a great focal point for grand society gatherings, was requisitioned by the military during the Second World War. Together with much of the countryside along this coast, the estate became part of a vast military training area in preparation for D-Day. The Hall, occupied by the Army, never recovered. Too damaged to be worth repairing, it was knocked down in 1951.

This sad event does not alter the fact that the village was a source of rest and recreation and indeed of hospitality for countless Ness personnel, both military and civilian. Its hostelries provided accommodation, venues for meeting and social gatherings, and at times, Officers’ Mess facilities. Its church tower was a navigational marker for many of its airmen, and its churchyard, sadly, a resting place for a few of them. Personnel from the Ness learned to regard this area as their ‘home from home’. It is remarkable how many preferred to stay in this part of Suffolk when their appointments at the Ness came to an end. Orford is an essential part of the story of Orford Ness, however secret the activity there was supposed to remain.

Whatever the season, the scene on the quay is seldom dull and in summer, ‘fishing’ for crabs provides endless excitement for the young. The observant may spot a highly significant craft, usually moored on the further bank, a substantial battleship-grey landing craft, which periodically crosses from its home on the Ness to run vehicles on and off from a ramp which slopes into the water. This vessel more than any other provides a graphic reminder of a military past.

For centuries, Orford Ness was known chiefly for the hazards of its notorious shore. It was always posing a potential threat to the busy passing traffic, shipping goods and raw materials down to London, as well as to the local inshore fishing trade. The call for some sort of aid to navigation reached a point in the seventeenth century when the need for action became irresistible. King Charles I was happy to grant a ‘patent’ to a private speculator rather than to Trinity House, one assumes because he could thereby benefit his Treasury.

A long sequence of pretty unsatisfactory wooden beacons followed, all in turn burnt down or washed away. The last of these was destroyed in a fierce storm in October 1789. The then owner, Lord Braybrooke, aware that this was a profitable asset that deserved a more robust construction, decided to construct a mighty new tower in stuccoed brick. It was completed in 1792. This is the lighthouse that has survived to the twenty-first century.

During the nineteenth century, the Orford Light was developed under the demanding stewardship of Trinity House, which acquired it by an Act of Parliament in 1837. Technical improvement followed, notably in the 1860s, when the eminent contractor James Timmins Chance installed new lenses and mirrors. Chance brought with him his consultant engineer, John Hopkinson, the inventor of a system for light flashing. His son was Bertram Hopkinson, who would play a vital role in the history of the Ness.

Further major development was undertaken during the decade before the outbreak of the First World War. The Orford Light was thus as advanced as any in the land when war broke out and the keepers found their whole way of life altered for good. From then on, they would have to share the Ness with new neighbours, both military and civilian.

This prelude to the Ness story aims to explain the setting and the context for events that took place there over the course of nearly eighty years when it was a secret place. Forbidding notices along the riverbank throughout this period used to warn people off: ‘WARNING: This is a prohibited place within the meaning of the Official Secrets Act. Unauthorised persons entering this area may be arrested and prosecuted’. Perhaps all this hardly welcoming message did was to stimulate an added curiosity as to what was really going on. Its new owner, the National Trust has, for obvious reasons, found itself seemingly only a little less forbidding. ‘Please keep out’, run its notices. ‘This site is not open to the public.’ The notice explains this apparently qualified welcome: ‘All the structures are very unsafe: There may be a risk from contamination and unexploded ordnance.’ Sadly, access to the secret site has to be managed and controlled, even as visitors are encouraged and warmly welcomed.

When the National Trust purchased the Ness in 1993, it rescued the site from serious neglect. Such neglect would not only have destroyed the intrinsic value of the place, but would have constituted a disgraceful insult to the memory of a legion of people who gave great service to their country. For the secret researches and tests carried out on Orford Ness played no small part in the resolution of the three great wars of the twentieth century: the First, the Second and the Cold.

So, even now that it is in the custody of the National Trust, Orford Ness may still give an impression of being essentially a secret place. There are no brown signboards with the familiar oak leaf logo to point visitors from far and wide in its direction. By design and by circumstance, the place maintains its obscurity. Only the determined and discerning press their way to the quay. They may quickly come to regard their passage across the river as an adventure into a land of secrecy, privacy, ‘cover stories’ and mystery; of curiosity, challenge, danger, discomfort, enterprise and invention. One thing is frequently observed and has often been repeated by those who worked on the site over the years. Here is a place with an amazing atmosphere, a bit of magic and, in its unique fashion, an unmatched beauty.

When the Ness was officially opened to the public in June 1995 it ceased to be quite the mysterious and secret site of the previous eight decades. Visitors at the rate of up to 7,000 a year come to satisfy their curiosity, and see the place for themselves. For a National Trust property, the numbers are small: a great house would welcome that many over a few weeks in summer. The Ness is not a grand landscaped estate or ornamental garden and it provides no stately home, and crowds of visitors filling the place would be quite inappropriate for what is above all a nature reserve.

VISITORS’ VOICES

This coast in general and Orford in particular has always enjoyed a long tradition of folk-tale and legend, of ghosts (M.R. James (1862—1936) the noted Cambridge scholar and writer of celebrated ghost stories, was greatly affected by East Suffolk), of smugglers and of violence. Here is the venue for the nineteenth-century romance of Margaret Catchpole and the smuggling fraternity. Latterly it has been the land of military secrets, and it has regularly provided inspiration for artists and writers.

The first and perhaps greatest interpreter of the Ness shore was J.M.W. Turner, who painted a number of watercolours as part of his important ‘East Coast’ collection during the 1820s.

Until it was opened to the public, descriptions with a Ness setting have been understandably rare. An exception appeared in 1938, when the thriller writer Richard Keverne, a former Royal Flying Corps (RFC) pilot, published his book The Havering Plot, set in a thinly disguised Ness. In 1992, shortly before the Trust takeover, the atmospheric writer and scholar W.G. Sebald paid a visit. A description of an afternoon on the site appeared in his memorable book The Rings of Saturn. He chose a rather gloomy day and was in a rather gloomy mood. Tellingly, and he was far from being alone here, he sensed what might be termed an ‘Ozymandias’ reaction to the evocative silhouettes of the nuclear bomb test labs on the seaward horizon:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare, The lone and level sands stretch far away.

(P.B. Shelley)

The Ness was open to the general public only from 1995 and so the opportunity for artists and writers to be inspired by the place has inevitably been restricted. In recent years, the Ness has proved almost irresistibly attractive to artists, writers and photographers, actively encouraged by the National Trust.

Two noted artists were commissioned to celebrate this occasion, John Wonnacott and Dennis Creffield. The latter produced a series of dark and threatening portraits of the labs, highlighting the violence they represented and the wildness of their setting. He argued that they should be seen as monuments and memorials to the Cold War, and the Trust has indeed followed his advice.

Essential to the cultural heritage of Orford is the medieval myth of the ‘Merman of Orford’. The story, as related by Ralph of Coggeshall, tells of the creature, half man and half fish, caught in Orford fishermen’s nets and forced by torture to reveal who or what he was. Terrified that they had captured a devil who might corrupt them, they hurled him back into the sea off the Ness, and he was never seen again. This legend inspired the then Poet Laureate, Sir Andrew Motion to write a major poem, published in the Independent on Sunday in July 1994. Here he subtly interpolates the Merman tale into his interpretation of the twentieth-century military activity.

As to other writers in recent years, these have largely been journalists, who have struggled to find sufficient information about the Ness, many sources remaining classified. Travel writer Christopher Somerville penned a portrait which appeared in The Sunday Telegraph in January 1998 and offers the best possible alternative to actually visiting the Ness. ‘It was’, he argues, ‘probably the nearest you can come in England to walking in the desert…’ The description given by the National Trust is ‘the last coastal wilderness in southern England’. Somerville explains how the unique feature of the ridges and furrows in the shingle beach, which appeared ‘to have had a giant’s comb dragged lengthwise along it’, were the product of centuries of wild storms. His is a brilliant picture in words.

Somerville reminded his readers of another feature of this Suffolk shore: its association with one of the great musicians of the twentieth century. Benjamin Britten, living locally most of his life, loved the characteristic sound of the Suffolk coast, and wove it into the fabric of Curlew River and Peter Grimes. For those with an ear for such a fantasy, the music of Britten and ghost of Grimes ‘at his exercise’ is never far away. For even if the air is still, there is the constant lap of water rolling up and down the shingle. The cry of swooping gulls is seldom absent. The constant winds blow through the railings on the staircase up to the Bomb Ballistics building’s viewing platform. It makes a steady whistle and hum, varying in pitch and volume, like some eerie invisible orchestra.

2

The First World War and the RFC comes to the Ness

The first manned flight by a powered fixed-wing aircraft took place in 1903. The significance of this momentous achievement by the Wright brothers in remote Kitty Hawk, North Carolina may not have been appreciated at the time, certainly in Europe. Indeed, initially it was scarcely acknowledged in the United States. While the Royal Aeronautical Society in London had inaugurated a lecture series in honour of Wilbur Wright as early as 1913, no equivalent event happened in America until 1937. A guest speaker at this inaugural event in the US was an Englishman, Professor Bennett Melvill Jones. He was one of many brilliant men whose flying career had been launched on Orford Ness in 1917. This curious lack of appreciation of the Wright brothers’ achievement in their own land can be illustrated by one other extraordinary fact. Their pioneering biplane spent all its early years on display in London, at the Science Museum. It was transferred to Washington’s National Air and Space Museum only in 1948.

The year 1903 was a significant year for other reasons. While a European war may not have seemed imminent, there were signs, on land and sea if not in the air, that an international war was a possibility. The very idea seemed to enjoy quite a degree of popular support. Jingoism was widespread. A German High Seas Fleet was being built, and a spy-thriller, published that same year, further provoked the fear that Britain could be attacked. Riddle of the Sands by Erskine Childers aroused some widespread interest, and was noted in official circles. It forecast a surprise invasion on the East Anglian coast by German barges. For a decade, similar wild plans were indeed in circulation around the German High Command, chiefly in order to curry favour with the anglophobe Kaiser. The idea was largely debunked by the more realistic Count von Tirpitz, architect of the Imperial German fleet and for nearly twenty years State Secretary of the Navy Office.

The main preparations for war on both sides of the North Sea did indeed tend to focus on naval developments. As early as 1909, the Royal Navy began to realise that the aeroplane might well have a useful part to play in future warfare. That year, Prime Minister Asquith set up an advisory committee under Lord Rayleigh to guide the War Office. He brought in professional academics to work with the military and the government, a cooperation that would be a major feature in the Orford Ness story over succeeding decades. Two years later, a generous benefactor, Frank McLean, presented the Admiralty with the site of its first air station at Eastchurch, to enable aviators to be taught to fly. In some respects, therefore, the Navy took the lead in aerial warfare. With an easily excited and air-minded First Lord of the Admiralty in Winston Churchill, this was hardly surprising.

The War Office created its air wing in 1911, the same year as the Admiralty. The Army was much more conservative however. There was widespread suspicion of noisy machines, which ‘might frighten the horses’. Initially, this air wing was to be no more than a branch of the Royal Engineers. Nevertheless, the recruitment of eager volunteers truly excited by the novel experience of flying led it to evolve rapidly into a unit in its own right: the newly designated Royal Flying Corps (RFC). It was founded in a formal and identifiable sense in April 1912 and was in operation a month later.

By 1913, it had established its headquarters at Farnborough and acquired a further station at Netheravon in Wiltshire, close to the vast military centres at Tidworth and Larkhill. It was also near what in May 1912 had become the Central Flying School for pilot training at Upavon, used by Army and Navy alike: its first commanding officer was in fact a naval officer, Capt. Godfrey Paine RN. He was appointed by an enthusiastic Churchill, and given just two weeks to learn how to fly in order to prepare him for his new role as Commandant.

At the same time, the Army was beginning to take the part the RFC might play in warfare more seriously. RFC requirements came to be given proper consideration. By the early autumn, various memos were in circulation defining the current state of the Corps, as well as indicating the priorities in realising its immediate needs. In particular, there was talk now of making provision in the military estimates for the purchase of land and the construction of barracks and special buildings. A plan was revealed, expanding the RFC to at least eight squadrons of aircraft by 1914. Of course, at that stage, the timing of the outbreak of a full-scale war could only have been surmised. A survey of resources around the British Isles was undertaken. This indicated just how few aircraft and airfields there were at this juncture. The bulk of these were in the hands of private amateur enthusiasts. The Army spelled out various criteria for selecting suitable sites for its airfields. The emphasis was clear: the RFC was to be seen largely as an adjunct to the land Army. Air stations must be near to existing concentrations of troops and used in their support. This perhaps explains the apparent preoccupation with sending RFC squadrons to Ireland, where the political tension was by then serious.

In view of the primitive and hence unreliable nature of the aircraft of the day, these air stations were to be ‘in the countryside and suitable for flying over’. Urban locations might be too dangerous. A 15-mile radius of open fields with low hedges and the minimum of woodland were suggested requirements, with the odd lake or proximity of the sea – ‘not less than 3 miles distant’ – to assist in navigation and orientation. A level strip a mile in length would be needed, with a site for accommodation barracks not less than 3 miles away. Just to complicate matters, and for fairly obvious reasons, a nearby town to supply a repair base was considered important. Railway access was also a recommendation. Reflecting on these recommendations, it is interesting to note how relatively few seemed to apply to Orford Ness.

In the light of this sense of increasing urgency, officers were dispatched around the country to recommend suitable sites. Perhaps typical of these tours was that by Major Brooke-Popham, who surveyed the area between Fareham and Cosham and other localities round Southampton Water. Major Brooke-Popham was to become a senior RFC officer and by 1919, a Brigadier-General and Director of Research, and thus closely involved in work on the Ness. By the 1930s he was the Air Chief Marshal who helped make the RAF ready for the next world war, but in 1913, following his tour of the countryside, he was unable to recommend a single possible site for the RFC. In addition, it was evident that during the last few months of pre-war calm, the landed classes were far from willing to consider sacrificing their private interests to any sort of national requirement. ‘Nimbyism’, a feeling of ‘not in my back yard’, was alive and healthy. In November 1913, a conference attended by no fewer than three Major-Generals (Cowan, Van Donop and Scott-Moncrief) was held to discuss the situation. A number of suggestions were put forward, like taking over the Dover Prison buildings to hasten the provision of an airfield in a strategic location, obviating the need to build barracks. By now, the southeast corner of England was identified as the crucial area for RFC deployment.

Shortly before this, in September 1913, correspondence within the War Office revealed the promise of a third air station, following on from Farnborough and Netheravon. ‘Purchase of some land at Orford Ness is about to be completed’, reported the RFC commanding officer, Brigadier-General David Henderson*, ‘and I propose to establish at least one squadron there. This station, which is on an island, [sic] is required to enable certain experimental work to be carried on in privacy. It is within reasonable distance of the troops at Colchester, Ipswich and Norwich.’ This same letter, with its very first reference to the Ness in the War Office files, mentioned a number of other places that were being targeted by the RFC, including sites in Chatham, Lydd, Hyde, Shorncliffe and Dover. One air station not listed was already established on rented property at Montrose in Scotland. It was from here that an early notable achievement by RFC aircraft is recorded. Six planes successfully flew the considerable distance to take part in summer manoeuvres in southern Ireland in 1914.

When war broke out, the Army operated just seven stations, a number that had risen to over 300 by 1918. Orford Ness had become a military site, and remained so for another eighty years. It can thus claim the distinction of being one of the very oldest air stations in England. However, for legal reasons, the acquisition was not totally straightforward, and this explains the considerable delay between the War Office statement in September 1913 and the actual arrival of the first aircraft over two years later.

The title deeds, now in the hands of the National Trust, show that the initial purchase was of some 155 acres of King’s Marsh, and is dated as early as 16 August 1913. The named vendors of this section of the site were Edward Moberly and Mary Louise Tyler. They appear to have been occupying tenants of what was a property quite seriously compromised by what the legal documents refer to as ‘adverse matters’. These were traditional grants in support of local parishes, manorial rights and customary agreements. One of these was a right to extract from the beach 150 tons of shingle per annum. The complicated business of dealing with tenancy rights and all other similar obstructions to acquiring the total freehold delayed matters until 13 December 1914. It had involved a certain amount of wrangling. Thus, the making of the grazing marshlands ready for use by aircraft was delayed and work cannot have begun until early 1915.

The main sale of the Ness was dated 20 January 1914 and referred to the bulk of the site. The price for the 1,500 acres of ‘Saltings’ and ‘Orford Beach’ was £9,250. A further £500 to obtain release from free rent and other commitments meant that the War Office ultimately paid a total of £13,750 for their Ness property. Eighty years later, the MoD’s asking price was a twenty-fold increase on this original purchase cost.

This land formed a peripheral part of the 11,000 acre Sudbourne Estate and its sale marked the beginning of its break-up, a fact of life for many large agricultural holdings during these years. Now owned by a very wealthy but improvident and extravagant Scottish industrialist, Sudbourne Hall was enjoying a terminal flourish of Edwardian splendour. Kenneth Mackenzie Clark restored the Hall, making it the happiest of homes for his noted son, Kenneth, later Lord Clark, of Civilisation fame. His grandson, historian and politician Alan Clark, will in turn appear later in the story of the Ness in his role of Defence Minister. The writing was on the wall and the decline of the estate culminated in the abandonment and demolition of the Hall in 1951.

So Orford Ness, well over 2,000 acres in all, for so long just an appendage to a great estate across the river, began to develop a significance and identity in its own right. This was based in large measure on the very fact that it was cut off from the mainland, affording, as the War Office described it, ‘privacy’.

For the reasons described above, there was an apparent hiatus before more frenetic military activity could begin in late 1915. What had in 1913 seemed ideal for the purposes of an experimental station from the viewpoints of location and availability was certainly not so ideal in terms of terrain. The marshland had to be transformed from its uses as grazing for livestock and as a playground for affluent sportsmen. There were channels and ditches and humps and bumps, all of which had to be transformed into a flat and essentially dry field suitable for take-off and landing. In fact from the outset it was more accurate to say ‘fields’, for a channel was left for the roadway (and later a narrow-gauge railway) leading from the jetty on the river to the station’s buildings. In effect there was a pair of airfields. Such an arrangement was not so uncommon in the early days: one thinks of Croydon or Lulsgate at Bristol. An accident on one side would not necessarily cause closure of the other.

There seems to have been no sign of any impatience at the delay in gaining access. It was always scheduled to be an experimental station and it could be argued that the RFC needed time to discover just what experiments actual warfare conditions at the Front would necessitate.

The arrangement of Britain’s air forces in 1914 was very much at a formative stage. The RFC, and the naval wing, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), each had a distinct area of responsibility. For a while, defending the coastline was seen as a job for the Navy: home defence was just a part of the RNAS brief. It was therefore Churchill from the Admiralty who defined the tactics for dealing with aerial attacks. This was the position in September 1914, at a time when the nation was defended by only seven operational RFC air stations; the prime responsibility of the RFC was to support the Army in the field, and not to protect the civilian population at home. The Navy and Army had scarcely 120 aircraft in service, less than half the number available to the numerically much larger armed forces of France, Germany and Russia.

The Admiralty directives argued that if possible, enemy aircraft be engaged at, or near, their bases, and that priority for locating anti-aircraft guns would go to military installations. Cities should receive no such protection but rely on blackout. The success of the first Zeppelin raids from 1915 prompted a more methodical defence arrangement, necessitating the creation of RFC’s so-called Home Defence squadrons, to work with the RNAS. This all resulted in various rivalries and inevitable conflicts. Home Defence squadrons for example did not take kindly to an experimental station like Orford Ness involving itself in its sphere of responsibility. There was a marked and fierce rivalry between the RNAS and the RFC.

When work on preparation of the military facilities began on the Ness, the Central Flying School had been established at Upavon. In late 1914, a unit known as the Armament Experimental Flight, commanded by Capt. A.H.L. Soames, M.C., was created, also at Upavon, to develop techniques and equipment for the effective tactical use of aircraft as weapons of war. This was the unit that was transferred to the Ness. Its functions shaped the sort of work that Orford Ness would be undertaking for the rest of its existence as a military site.

In an almost lyrical passage in his book Secret Site, Gordon Kinsey suggested that the impact on the servicemen involved in the move to East Anglia must have been pretty shattering, even by wartime standards. It will have seemed: ‘…a scene of complete desolation. After the rolling hills of Wiltshire this flat, lonely marshland, barely above sea level, with its bitter easterly wind, must have made the new arrivals wish they had been posted anywhere else but here.’

Initially, it seems that accommodation had to be found for many of the troops in Orford itself and the officers used the Crown and Castle Hotel as their ‘mess’. This was to be far from the only time that this hostelry was to play its part in the work done on the Ness. Orford’s fine Town Hall, the gift to the community of the 4th Marquess of Hertford, was for a while used as station headquarters.

Gordon Kinsey quotes a recollection of an Orford inhabitant, Lou Anderson, the village tailor:

We were all excited one day to see the arrival of six large RFC lorries, as our village was at that time a backwater and large lorries were not an everyday sight. They were loaded with large bales of canvas and long poles, which turned out to be portable hangars for aeroplanes. Other large and small items of equipment could be seen piled up on the backs of the vehicles as they trundled through the village down to the quay.

The recreation ground was commandeered for marquees and bell tents, while the officers were billeted in the hotels and other larger houses. Mr Friend’s Garage was used as the motor transport depot and boats were acquired to ferry the men across the river each day until more permanent facilities were constructed. The sight of so many servicemen must have come as both a thrill and a shock to the local population.

Primitive buildings, mostly of a pre-fabricated wooden type, were erected for the troops and for administration, while the aircraft were initially housed in canvas hangars. These were essentially tents, shaped to accommodate the wings and fuselage of a single aeroplane. During 1916 larger canvas hangars and rectangular wooden Bessoneau hangars (a type named after its inventor) were erected, to be followed later by two even larger and more permanent structures, the so-called Belfast Truss constructions. In 1918, a pair of the largest hangars of all was built to house twin-engined aircraft. These seem to have been to a design unique to the Ness and they were sufficiently strong to give many decades of service.

All these buildings were arranged in a long sprawl on the eastern side of the fields, about 1 kilometre from the river jetty. On the seaward side of these buildings was the tidal creek, Stony Ditch, which separated the marshland from the great shingle spit, at this point around 800 metres wide. A very clear picture of how these buildings were arranged is provided by a series of aerial photographs taken in 1917 and 1918 (see Plate Section).

The actual opening of Orford Ness took place during October 1915. The official commissioning of the Ness station came the following year, on 15 May 1916. The first squadron to arrive was given the number 37, and came from the Experimental Flying Section from within the Central Flying School in Upavon, but it would be a mistake to describe the personnel or planes on the station in terms of defined or fixed squadrons. A constant flow of aircraft and people came and went, constituting the Orford Ness Armament Experimental Flight.

From early 1917, there was an added complication over nomenclature and staffing. The Experimental Flight, which had begun work on the Ness in 1916, was to grow into a greater and more imposing organisation. The Ness was no longer quite extensive enough. Two important officers were dispatched from the Ness to Ipswich to look for another airfield site, to extend the trial facilities. These were Lieutenant Henry Tizard and Captain Bertram Hopkinson, both archetypical Ness figures, high-powered and extremely brave, and very notable academics. They observed that a field on Martlesham Heath, part of the Pretyman estates, which stretched northwards from Orwell Park at Nacton to the east of Ipswich, was already being used as an aircraft landing field. Their recommendation was that the whole site be acquired.

Martlesham Heath opened in January 1917 as the RFC Aeroplane Experimental Research Station. The Ness meanwhile had its title defined as the RFC Armament Experimental Research Station. From 1920, the word ‘Establishment’ replaced ‘Station’ and in 1924, with the reopening of Orford Ness after a temporary suspension, the whole organisation of the two stations was officially called the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE).

For several reasons Martlesham immediately assumed the ‘senior’ status. Martlesham was considerably bigger than the Ness. It was closer to a large urban centre, Ipswich, and located beside the A12 road and just a mile from Bealings station on the Lowestoft branch of the Great Eastern Railway. Over the years, the two air stations shared research projects and the personnel to conduct them. Indeed, it is almost impossible to claim that a Martlesham pilot was not also an Orford Ness pilot. Similarly, another smaller research field was established a year later, in January 1918, at Butley, a heathland site in the Rendelsham estate.

A host of trials and experiments took place at all three stations, and indeed at a fourth, attached to the seaplane base at Felixstowe. So, by the end of the war, four of the seven experimental air stations in the hands of the RAF were located in this cluster in east Suffolk, and further south, beside the Medway in Kent, was the naval equivalent, the Isle of Grain Research Station, also transferred from Upavon.

The two stations at Orford and Martlesham rapidly established an enviable reputation for skilled flying, meticulous attention to detail in their researches and for bare courage in what could be a highly dangerous occupation. Moreover there was a constant turnover of personnel, with plenty of interchange between the two stations. Describing these pilots, the historian (and former Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) officer) Constance Babbington Smith wrote: the very name Martlesham came to stand for everything that was most accurate and thorough in test flying. A Martlesham pilot was by definition one who could turn his hand to testing any variety of aeroplane and a Martlesham report meant a report that indicated an analysis of unprecedented detail and comprehensiveness.’ Gordon Kinsey confirms that ‘to be a Martlesham test-pilot was to be one of the elite of the profession’. These tributes applied no less to an Orford Ness test pilot. To be an Orford Ness scientist, boffin or pilot was to demonstrate the highest standards of research, worthy of any great university. This is indeed where so many of these men came from.

It would be perhaps a mistake to attempt to define a tidy or conventional hierarchical structure for the operation of these stations. In the case of Orford Ness, there was a Commanding Officer, in the rank of Major or Lieutenant-Colonel. His job was to become increasingly administrative, running the organisation of the station, which by 1918 on the Ness was to grow into a sizeable unit, with over 600 men and women on site. He also held overall responsibility for conducting the trials. His signature would follow that of the trials officers in the official reports. Major Wanklyn was the inaugural Commanding Officer (C/O) until early 1917. It is significant, just to indicate how blurred the lines of authority were, that he was a regular pilot in trials and clearly wanted to be involved. Wanklyn was followed by Major J.B. Cooper, whose appointment coincided with a number of changes in personnel. In spring 1918 he was replaced by Lieutenant-Colonel Shackleton, who presided over the transfer from RFC to RAF in April 1918. By the end of the war, Lieutenant-Colonel Boddham-Whetton had taken over.

Above the C/O was the highly significant figure of Major, soon promoted Lieutenant-Colonel Bertram Hopkinson, who acted as mastermind and liaison with the War Office. The naval analogy would be that of the Commodore in his relationship with the Captain of a flagship. Hopkinson helped set up both the Ness and Martlesham. Sadly, he died shortly before the end of the war, and no replacement was appointed to fill the post.