8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

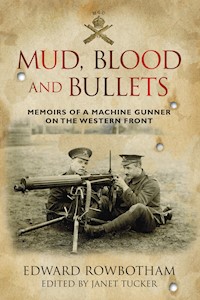

It is 1915 and the Great War has been raging for a year, when Edward Rowbotham, a coal miner from the Midlands, volunteers for Kitchener's Army. Drafted into the newly-formed Machine Gun Corps, he is sent to fight in places whose names will forever be associated with mud and blood and sacrifice: Ypres, the Somme, and Passchendaele. He is one of the 'lucky' ones, winning the Military Medal for bravery and surviving more than two-and-a-half years of the terrible slaughter that left nearly a million British soldiers dead by 1918 and wiped out all but six of his original company. He wrote these memoirs fifty years later, but found his memories of life in the trenches had not diminished at all. The sights and sounds of battle, the excitement, the terror, the extraordinary comradeship, are all vividly described as if they had happened to him only yesterday. Likely to be one of the last first-hand accounts to come to light, Mud, Blood and Bullets offers a rare perspective of the First World War from an ordinary soldier's viewpoint.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

He asked, ‘Is this the gun that’s been firing all night?’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘Is anything wrong?’

‘Far from it,’ he replied. ‘We’ve been out in front all night repairing the wire and the Jerries have been trying to sneak forward, throwing hand grenades. They couldn’t quite reach us, thanks to your gun. Now there are seven of ’em lying on their own wire.’

I should have been delighted with this news, but I was not. I found I gained no satisfaction from it whatsoever; in fact, I was overcome by a feeling of deep remorse. ‘Revenge is sweet’ as the saying goes, but not for me. This may sound daft coming from a soldier on the front line of a war, but for the first time I felt like a murderer. All day I could not stop thinking about those seven men; men I had killed in revenge for my brother. Those men probably had brothers too, who would be mourning them, just as I was mourning Tom, and I had created another seven sad families.

CONTENTS

Title Page

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

FOREWORD TO THE ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPTMEMOIRS OF A PLEBEIAN

CHAPTER ONE A WORKING CLASS LAD

CHAPTER TWO SCHOOL DAYS – QUEEN VICTORIA’S JUBILEE

CHAPTER THREE THE BOER WAR – WORKING LIFE

CHAPTER FOUR 1915 – JOINING KITCHENER’S ARMY

CHAPTER FIVE DEPARTURE FOR THE WESTERN FRONT

CHAPTER SIX YPRES – LIFE UNDER FIRE

CHAPTER SEVEN SOMME OFFENSIVE – BATTLE OF FLERS

CHAPTER EIGHT HOME LEAVE – THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES – PASSCHENDAELE

CHAPTER NINE THE BATTLE OF CAMBRAI

CHAPTER TEN PROMOTED TO SERGEANT – DEATH OF PRIVATE CHATWIN

CHAPTER ELEVEN WOUNDED AT MOUNT KEMMEL, YPRES, THE MILITARY MEDAL – THE ARMISTICE

CHAPTER TWELVE MARCH TO THE RHINE – DEMOBILISATION

CHAPTER THIRTEEN BACK TO BLIGHTY – MARRIAGE – AUSTRALIA

EPILOGUE

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly, my grateful thanks go to the members of the Machine Gun Corps Old Comrades Association, who continue to work so hard to keep and honour the memory of the 170,000 men who served in the Machine Gun Corps from 1915–1922. I would especially like to thank Graham Sacker, Judith Lappin and Andy Bray for their help, and for welcoming me so warmly as a new ‘Old Comrade’. I am also indebted to Bill Fulton of the Machine Gun Corps History Project, and his colleague Phil McCarty, for their generous assistance and unfailing patience in answering my many email queries.

I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Shaun Barrington at The History Press, for his belief that these memoirs were worthy of a ‘proper’ publisher, and to my editor Miranda Jewess for her help and support. Also, if I may, I would like to say an enormous thank you to my lovely, long-suffering husband Graham, who has spent these past months covering all the jobs on the Home Front while his wife has been ‘living’ in the trenches of the Western Front. Thank you also to family members who scoured their attics for photos, especially Chris Hill and Graham Foxall.

Lastly, and most importantly of all, I want to thank my mother, Edward Rowbotham’s much-loved daughter, who not only gave her permission for me to take away and edit Grandad’s notes and memoirs, but regularly sat uncomplaining while I ransacked her sideboards and cupboards in search of medals, family mementoes and old photographs.

INTRODUCTION

The Great War, the one that was supposed to ‘end all wars’ but, of course, did not, has a unique place in British history. We remain fascinated by it – even 90 years on. We remember it because of the sheer numbers of young British men who fought in it for their country – more than in any other war either before or since – and the fact that many of these men did not belong to the regular army but were volunteers and conscripts. We also remember it for the dreadful toll of the slaughter of these young men; by the time of the Armistice in 1918 nearly a million of them were dead or missing, and around another million wounded. Edward Rowbotham, my grandfather, was one of the volunteers.

What life was like for the common soldier on the front line during the four years the war raged has, of course, been documented; however, most of the literature – books, memoirs, diaries – have been written by academics, politicians and officers, people who did not experience the war from quite the same perspective as the rank and file. There have been comparatively few detailed first-hand accounts written by the common soldier.

People born into the generation who could remember the First World War are gone now, and gone with them is the likelihood of obtaining any more first-hand accounts – which makes my grandfather’s memoirs a precious piece of history, possibly one of the final first-hand accounts to be discovered.

Edward Rowbotham was born in 1890, one of fourteen children from a working-class family in the Black Country at the end of the Victorian era. Although the Rowbothams were a loving and close family, there were so many mouths to feed that Grandad was no stranger to hardship and deprivation as he was growing up. He was a young man of 24, a coal miner, at the time Britain declared war on Germany. From the start he was desperate to join up, but he was by that time one of the principal breadwinners in the family and couldn’t be spared. Lord Kitchener kept pointing to him personally from the posters, telling him his country needed him, but he didn’t need telling; he truly wanted to be a hero, a ‘glory boy’, as he called it. He finally enlisted in November 1915, proud to accept the King’s Shilling and become one of Kitchener’s Army. Even when he realised, too late, that he had volunteered himself to fight at the very gates of hell, his sense of duty never faltered. He would see it through without complaint. ‘I just got on with it and made the best of things,’ he would always say about it afterwards with typical understatement.

He enlisted as a private in November 1915, joining the 5th South Staffordshire Regiment, but from there he was drafted into the newly-formed Machine Gun Corps and sent to the Western Front. There, he fought in every major conflict from March 1916 onwards, at Ypres and on the Somme. Men of the Machine Gun Corps, specially trained in the operation of the Vickers light automatic machine gun, were always deployed on the front line of the battlefield, sometimes even ahead of it in no-man’s-land, and sitting targets for every weapon the enemy could throw at them; so much so that members were sometimes known as ‘the suicide club’. Casualties, inevitably, were enormous. Of the 170,000 officers and men who served in the Machine Gun Corps, 62,000 of them became casualties (over 36 per cent): of these, nearly 14,000 were killed, and a further 48,000 were wounded, missing or prisoners of war. Edward Rowbotham was extremely lucky to be one of the survivors.

Uncomplaining, he endured the horrors and the brutal hardships of the trenches, his courage, stoicism and good humour seeing him through the darkest times. His passion for life never left him – there were even times when he actually seemed to enjoy the war. As a soldier he fought bravely and did his duty, which was to kill as many of the enemy as he could, but he was essentially a kind and gentle man. He had enormous compassion for his fellow man, on one occasion risking his own life to rescue, under enemy fire, one of his gun team, mortally injured in no-man’s-land, so that his comrade would not be left to die in a shell hole (every soldier’s dread) – an act for which he was awarded the Military Medal.

He wrote these memoirs in 1967, 50 years after the war, and yet he describes life in the trenches so vividly, as if the events had happened to him only yesterday. An enthusiastic storyteller, with excellent powers of recall, he had an amazing capacity for bringing his experiences to life. The stories he recounts I heard as a child many times (I adored him, my lovely brave Grandad, and I loved to listen to his tales of heroic deeds) and this helped me to edit his memoirs with confidence, enabling me to clarify the odd point where necessary, even adding the occasional titbit of information, which, for whatever reason, he omitted from his written account.

I know he wouldn’t mind a bit that I have changed his title. He gave his book the title Memoirs of a Plebeian. He described himself as a ‘plebeian’, meaning an ordinary working man, but there was nothing ordinary about him at all. He was a funny, articulate, highly intelligent man, who happened to be born into the lower classes at a time when it was almost impossible to move up. Opportunities were simply not there for him; had he been born today, I am certain he would have gone to university (Oxford probably, as his great grandson did a century later) and he would have had a good career, earning the kind of money Grandad spent his life hoping for, but never found.

Why it has taken over 40 years to approach a publisher with these remarkable reminiscences is a mystery. After he completed his memoirs (all painstakingly handwritten on foolscap paper and ‘professionally’ glued into a home-made binder, with the title on the front improvised from letters cut out of the Daily Mirror) Grandad passed it round the many and various members of the Rowbotham clan, and we all read it. I was only twelve at the time, and although I was given them to read I was still too young to really appreciate their importance.

After Grandad died in 1973, ‘The Book’, as he called it, was put away in Mum’s sideboard along with other treasured family keepsakes, like his Military Medal. Then, around the times of the 90th anniversaries of the battles of the Somme and Passchendaele, there seemed to be renewed media interest in the First World War, with books and TV programmes and many articles appearing in the newspapers. Mum remarked to me, ‘Your Grandad fought in the Battle of the Somme, and at Passchendaele – and he managed to come home in one piece at the end of it. He wrote about it all in ‘The Book’.’

Of course he did! I took out ‘The Book’ and began to read it again. It didn’t take me long to realise that it was more than just a family memoir, it was an important piece of history: a detailed and fascinating first-hand account of an ordinary soldier’s experiences of the Great War. I was determined to see if I could get it published for him.

So, here they are: my Grandad’s memoirs, lovingly revised and edited by his granddaughter. I have two regrets. The first is that he is not here to see ‘The Book’ in print (he would have been so proud); the second that he is not here to answer the very many questions I desperately want to ask him about his extraordinary life. But then, as Grandad always used to say, ‘You can’t have everything, can you?’

He dedicated his memoirs to his daughter and grandchildren; now I feel very proud indeed to dedicate them to his memory.

This is his story.

Janet Tucker

FOREWORD TO THE ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPT MEMOIRSOF APLEBEIAN

When I decided to write my memoirs I had two objects in view: firstly, to occupy my time in retirement, and secondly, to provide a record of events of my own lifetime, indicating the way of life enjoyed (I use that word loosely) by my generation of working class people.

I have wondered many times what life was like in my father’s and grandfather’s times. So, I propose to set down something of my life and times on the assumption that my grandchildren and their grandchildren in turn might wish to know what life was like for an ordinary working class lad growing up in the Black Country in late Victorian and Edwardian times; and then, as a young man, going to fight for his country on the bloody battlefields of the Western Front; then afterwards, on returning to normal life, how he coped (I use that word loosely too) with the aftermath of war.

I have called myself a ‘plebeian’ rather than a ‘working man’ because almost every man calls himself a working man and I wish to confine my observations to the class of people who have to work in order to live; in other words the Common Man.

Much has been written about the Great War, but the accent has invariably been on the exploits and habits of people in high places – the politicians, generals and officers. Not so much has been written from the viewpoint of the common man. These memoirs represent that point of view, and they are a true record of my own life.

Edward Rowbotham, 1967

CHAPTER ONE

A WORKING CLASS LAD

I was born in the year 1890, the seventh child of a family of fourteen (fifteen if you count a twin who died at two months). My brothers and sisters were, from the eldest down, Harry, Len, Albert, Ernie, Ada, Edie, Me, Gertie, Tom, Edgar, Hilda, Nellie, Frank and George. At the time of my birth we lived in a small terraced house in Reeves Street, Bloxwich, in the Midlands.

My dad was a hard-working man and loved his family. He was a coal miner and good enough at his job to earn as much money as the next man, though that was little enough in all conscience. He liked his drink of beer, but only imbibed when he could afford it. He never went to school, so could not read or write – but he had the intelligence to actually teach himself to read once he was forced to give up work when he was only 50 through ill health brought about by the abominable conditions which prevailed in the pits in the Midlands at the time.

The pits were grim, most of them wet and damp, and often men would be working all day in water over their boot-tops. Ventilation was so bad that, more often than not, the air was polluted, filled with powder smoke from the blasting operations. Not many men of my dad’s generation continued to work after the age of 50 or so. Penal servitude would have seemed like a holiday to them; after all, the convicts at least had fresh air to breathe.

My mother, bless her, was a fount of wisdom and knowledge, and ‘Mother Confessor’ not only to her family but to her friends and relations as well. Not only that, she could read and write, no mean achievement for her generation. She possessed a fine sense of humour – she needed it with fourteen children – and the family was a happy one. We were devastated when she died at the age of 55, and it seemed to us ironic that she should be taken just at the time she could have started to enjoy her grown-up family. My sisters, Ada and Edie had to take over the responsibilities of the household, assisted by Dad, who was practically an invalid himself by then, although he lived to be 71.

We were a close-knit family, but as I look back now I realise what an immense struggle it must have been to raise our mob. There were already nine children before the first one, Harry, was old enough to go out to work. It is hard to imagine now what it must have been like with a house full of kids and only one worker to support us all. The burden of the household duties fell on my mother. She worked day and night to keep us fed and clothed, proud that she managed it without ever having to apply for Parish Relief. Parish Relief was only one step short of the shame of being sent to the workhouse – an ever-present threat to large families.

Many families where the father couldn’t, or didn’t want to work, or was not very good at managing the household finances, or he spent too much of the household finances in the pub, would end up in the workhouse. The workhouse was a wretched place, where the family would be subject to humiliating conditions. Charles Dickens wasn’t exaggerating.

By the grace of God we never reached that stage, and it was my parents’ proud and justifiable boast that none of their children had ever gone to bed hungry. On the contrary, we considered ourselves well-fed. Mother baked all our own bread. She baked once a week, enough bread to last until the following week, and when the day’s fragrant baking was piled on the table, anyone who didn’t know us would have thought we were preparing for a siege. The highlight of baking day, to us children at least, was the time for the removal from the oven of the flap-jacks, which, when cooked, were about six inches in diameter and about an inch and a half thick. Mother would give us one each while they were still hot, and we would separate them and put in a slice of cheese or a knob of butter. The heat would melt the filling and they were delicious!

It was an awe-inspiring sight to see the family at meal times, particularly at Sunday dinner, when we were all round the table. The size of the meat joint would make some of the offerings you see in shops today look very puny indeed. In winter the evenings would be spent talking about pit-work, Dad and the elder brothers discussing the day’s happenings down the pit, what they said to the ‘gaffer’ or what the ‘gaffer’ had said to them or, when Len was at home, listening to him play the organ. Mother would be darning socks, or making a dress or pair of trousers for one of us, the girls washing up or tidying a room, the younger ones playing Ludo or draughts or snakes and ladders. Then Dad would say ‘Come on, that’s enough, let’s ‘ave yer up the wooden hill!’, and Mother, assisted by my sisters, would prepare the younger ones for bed, and, when all the children had gone up, it was suddenly very peaceful.

Sunday evenings were the highlight of the week. Len would be at the organ, and the family would gather round singing hymns with such gusto that often there would be quite a crowd gathered outside our front window. Although we weren’t church-goers it was a strict rule that only hymns should be sung on Sundays. Len offered to give me lessons on the organ as I was so keen on playing it, but alas, after about six lessons he started courting a young girl, so it is easy to guess what happened to my music tuition after that. Nevertheless, I kept on practising, and I was so eager to play that practically all my spare time was spent at the organ. Although I couldn’t read music, I eventually taught myself to play quite a number of tunes by ear; in fact, I progressed well enough to deputise for Len at our Sunday sing-songs when he was absent.

Our house around this period was hardly ever without visitors. Friends of my older brothers or my Dad would come to have a look at the pigs we kept in the yard, or to discuss their work in the pit. At weekends, particularly on a Sunday morning, we always had visitors and the parlour would be thick with tobacco smoke, and the conversation would be about – guess what? Pit work! I think my mother and sisters could have worked a coal mine; they heard so much about pit work they could give a competent message in detail to one of the night shift from one of the day shift.

One visitor, Tom Holden, who was one of Albert’s pals, bought a new gramophone, an Edison (which as a cylindrical type should have been called a phonograph, but we called them all gramophones). It was his very proud possession. We prevailed on Tom to bring it round, and the first time he brought it we were enraptured and mystified as to how a person’s voice could be made to come up a little trumpet like that. The records were cylindrical and cost sixpence each. The general verdict was ‘whatever will they think of next?’

Seeing the new gramophone and how it worked solved a mystery for me, for I had actually seen and heard one some time before at Leamore Flower Show. It was up on a platform with the gramophone itself resting on a large box. We were all eagerly waiting for the gramophone recital to start and when it did we were flabbergasted to hear a man’s voice coming up through the trumpet. We couldn’t believe it and thought somebody was having us on. We were convinced they had a man hiding in the box underneath, singing the songs.

CHAPTER TWO

SCHOOL DAYS – QUEEN VICTORIA’S JUBILEE

Life at school was no bed of roses. The teachers wielded the cane far too frequently and it was little consolation to us when our elders told us how lucky we were to be getting a free education and that ‘we didn’t know we were born …’ Inwardly, I thought it was they who were the lucky ones, not having to go to school.

Out of school hours, of course, we were much the same as any other generation of kids – noisy, mischievous and full of the joy of life. And the best part of school, naturally, was the holidays.

Bloxwich Wake, the annual fair and one of the highlights of our year, always came in the August holidays. The excitement would mount as the Wake ground began to fill up with caravans and all the paraphernalia of the side-shows, coconut shies etc, all horse-drawn. Most of the big attractions, such as the gondolas, the mounting ponies, the steam boat and Pat Collins’ own big show were drawn by a huge steam traction engine which operated between the Wake ground and Bloxwich railway station, where it would arrive on flat trucks. This is where us kids came in. One of the workmen would put a megaphone to his mouth and bawl out, ‘Come on lads, down to the railway station and help unload the trucks!’ We would be promised free admission to the Wake in return for our labours, so down to the station we would race, hundreds of us it would seem.

The workmen would attach a thick heavy rope to whatever it was to be unloaded, while the kids would be positioned along the length of the rope, one each side alternately. And then we would start to pull. The first pull would be from the siding to the gates, and a second pull would move the object up onto the road so that the traction engine could be hooked up to it. When there were enough objects hooked up to the traction engine it would haul them all up to the Wake ground, while another ‘train’ of stuff was hauled into position by kid-power. Those wake folk certainly knew what they were doing, using us kids as a free haulage machine. Of course, we were under the fond delusion that they would keep their promise to let us in for free (admission was 2d for adults and 1d for children), but when our work was done we were not even allowed to stay in the ground to watch the roundabouts assembled; as soon as the last load was hauled in from the station they would round us all up one last time and tell us to clear off, much to our disappointment.

‘We won’t ’elp ya next year. You can pull the rope yourselves,’ we would plead, but to no avail.

‘Gerroff!’ would be their final word on the matter.

A year is a long time in a youngster’s life, however, and by the time the Wake came round again it was forgotten and we would fall for the same trick all over again.

While I was still very young I saw, with others, a phenomenon which I have not seen since that time and have often wondered if I could have dreamt the whole thing, and if I told the story so many times that I had come to believe it myself. It was summer and the morning was sultry and close, and shortly before we were to be let out of school for the lunch break, a heavy thunderstorm broke. It was so severe that we were kept in school until it abated. When we were eventually let out, the water was gushing down the street gutters and almost overwhelming the drains and, like boys of all generations, we rushed to paddle in it. To our amazement we found that there were hundreds of little silver coloured fish in the water, not more than about half an inch long. As the water receded they were left high and dry and flapping about all over the place. At the end of afternoon school, we returned to look for the fish and found the poor things lying in the gutters – all dead.

I have, during the course of my 77 years, told this story many times to many different people. Sometimes I have been believed, but at other times I have sensed a certain disbelief, never openly contradicted, but just a wry smile perhaps, or a doubtful glance. When I decided to write these memoirs, I thought I would try to have the story verified, or otherwise, by writing to the BBC Weather Unit – and I received this reply:

Room 4095

Weather Unit

BBC

1st April 1967

Dear Mr Rowbotham

Thank you for your letter. The event you mention is certainly possible meteorologically speaking. When violent, thundery conditions exist, there is also a tendency for water-spouts and whirlwinds to form locally. In the case you describe, water from a pool or lake could have been sucked up into the clouds, and the whole lot, water, fishes and all, dropped some distance away.

Mind you, this does not happen frequently, although one or two similar occurrences have been reported from various places.

Yours sincerely

P.H. Walker

Well, fancy that!

There is another incident from my school days that I think is worth recording, particularly in view of all the stress we seem to lay on hygiene these days. I refer to the Christmas ‘Scrum’. This was when sweets were given out to the children before breaking up for the Christmas holidays. Now, whether the teachers did it this way for the children’s benefit or for their own malicious enjoyment we never knew, but instead of giving every child a few sweets each, which would have been the fairer way, one of the big classrooms would be cleared of desks. Whether the floor was swept I do not remember, and at that age I probably didn’t care. All the children, large and small, would be assembled in the classroom. Then, the teachers would come in carrying huge bags of sweets and start throwing the sweets up into the air, trying to reach all four corners of the room so that everyone would have a ‘fair’ chance of getting some. Well, the noise can be better imagined than described, and it was definitely a case of survival of the fittest, the oldest and the tallest, as the big boys pushed the little ones aside and grabbed the lion’s share.

Some boys – it always seemed to be the same ones – ended up with their pockets bulging, while the smaller boys got just a few. The teachers always appeared to be having the time of their lives. Wrapped sweets were unknown in those days and often the sweets were retrieved from the floor covered in dust and bits of fluff. The teachers would tell us, ‘You have to eat a peck of dirt before you die’, and, thinking about those Christmas scrums, I suppose we must have done.