15,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Ribbon of Wildness

- Sprache: Englisch

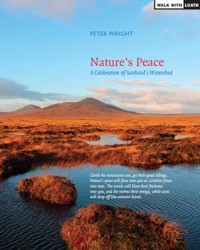

In 2005 Peter Wright walked the 1,200 km length of the Watershed in 64 days. Walking along the very spine of Scotland he was struck by the magnificence and diversity of the landscapes which his original and little publicised route exposed him to. Nature's Peace celebrates these landscapes as never before through stunning photographs, taking the reader on an imaginary journey from the English border in the south to the Shetland Isles and Unst at the very northern tip of Britain. Wright brings his journey to life with vivid descriptions of the land's history and discussions about its future.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 146

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Nature’s Peace

A Celebration ofScotland’s Watershed

Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves. JOHN MUIR

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Ribbon of Wildness

Walking with Wildness

Nature’s Peace

A Celebration ofScotland’s Watershed

PETER WRIGHT

LuathPressLimited EDINBURGHwww.luath.co.uk

First published 2013

eBook 2014

ISBN: 978-1-908373-83-0

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-94-6

The publishers acknowledge the support of Creative Scotland towards the publication of this volume.

Map by Jim Lewis

The author’s right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Peter Wright

Dedication

Nature’s Peaceis dedicated to all those who voluntarily take the time and the trouble to inspire a love of Nature’s wild places in those around them, especially in young people. Their generous influence is a beacon of goodness, which touches many lives, and enriches the human spirit.

Contents

Foreword – Stuart Brooks, Chief Executive, The John Muir Trust

Acknowledgements

Map

Nature’s Peace – a poem

CHAPTER ONE Welcome to the Watershed – Our Ribbon of Wildness

CHAPTER TWO The Reiver March – Through the Southern Uplands

CHAPTER THREE The Laich March – Linking Wildness with Wildness

CHAPTER FOUR The Heartland March – Cresting the Mountains

CHAPTER FIVE The Moine March – Through the North-West

CHAPTER SIX The Northlands March – Across The Flows

CHAPTER SEVEN The Viking March – Between Ocean and Sea

CHAPTER EIGHT Threats and Conservation – Creating a Legacy

CHAPTER NINE An End that is Just the Beginning

Photography and other key web-links

Environmental Abbreviations

Glossary

Foreword

The immense fund of inspiration about the Natural World that we can draw upon from the writings of John Muir is even more cogent today than it was when he first committed his thoughts and feelings to paper over a hundred years ago. ThatNature’s Peace, the title of this book, should be selected from one of his most popular quotes, is fitting indeed, as we prepare to mark the centenary of his death and reflect on his legacy. It gives me particular pleasure to provide a brief introduction to a book that will surely be appreciated and enjoyed by many. Peter Wright has created a landmark in the ever growing library of books about the landscapes of Scotland.

Although the concept of the Watershed, the backbone of Scotland, may be a very simple one, the landscapes of this geographic feature demonstrate a complex mix of widely differing types of terrain, and the rich habitats that they support. The evident wildness that binds all this together gives it a unique distinction, one that is noteworthy and invites celebration. People play an essential part in all of this, with a pride in their particular parts of the Watershed, and for those who visit from elsewhere, there is unlimited fulfilment and potential challenge.

The collection of pictures inNature’s Peacetake us on an evocative journey, spurred on by the evident talents of the many photographers who have contributed so generously to this fine book. Each has captured something of what they both saw and felt about the many different locations on this special journey, and given us something to enjoy. Together, they have provided the means to appreciate the landform of Scotland in a new way.

So, it is my hope that you will find something enriching for both mind and spirit within the pages ofNature’s Peace, that you will discover a new dimension to the landscapes of Scotland, and capture for yourself a good measure of Muir’s love of wild places. I also hope that this book inspires you to take your own journey into the wild and think about how you can ‘do something for wildness and make the mountains glad’.

Stuart Brooks

CHIEF EXECUTIVE, JOHN MUIR TRUST

Acknowledgements

Many motivated and generous people have contributed toNature’s Peace, and in a variety of different ways.

I am especially grateful to Alex Wood for the professionalism, attention to detail and practical advice which he so freely gave in the editing and proofreading that he carried out. To Liz Lefroy for her tact and skill in helping focus my poetic effort. To the following people who have used their photographic skills and talents to such good effect, and captured so many landscapes and moments – indeed the very essence ofNature’s Peace: Keith Brame, David Lintern, Nancy Chinnery, John Thomas, Ruth Longmuir, Hannah Longmuir, Malcolm Wylie, Gavin Crosby,Kerry Muirhead, Nick Bramhall, Chris Townsend, Fraser McAlistair, Peter Woolverton, Anna Woolverton, David MacFarlane, Katrina Martin, Mary Bates, Marie Lainton, Kirsty Bloom, Colin Meek, Nick McLaren, Norrie Russell, Colin Gregory, Fiona Isbister,NTSLibrary, Mike Pennington, Calum Toogood, Frank Hay, Kenneth Wright, James Wright, Mike Watson, Jen Trendall, Richard Kermode, Alan Bowie, James Macpherson, Richard King, Nigel Brown, Larry Foster, Jim Shedden, Rob Beaumont, Frank Brown, Richard Webb, Chris Dyer, John Tulloch, Hayley Warriner, Calum Togood, Kathryn Goodenough, Ewan Lyons, Andy Hunter, John Ferguson, Stephen Middlemiss, Andy Wilby and Jim deBank.

Peter Wright

Great Glen Sunset

The wonder of sunset uponthe Great Glen to Loch Ness, from Creag nan Gobhar.

Kirsty Bloom, Great Glen Hostel

NN315985

Nature’s Peace

Come, come away from the crowd,

take unhurried time,

leave the familiar order of things

and dare.

Discover Nature’s high places,

and go beyond the mundane to push yourself.

Tread lightly upon this fine green ribbon in the landscape

to find more of your spirit,

in all the possibilities

of this promising engagement

with wildness.

PETER WRIGHT

Carrifran Fencewalkers

Fence-walkers pause on their patrol round the high rim of Carrifran Wildwood, Borders Forest Trust.

John Thomas, John Muir Trust

NT159138

Chapter One

Welcome to the Watershed –Our Ribbon of Wildness

Do something for wildness and make the mountains glad. JOHN MUIR

Within the pages ofNature’s Peace, you are invited to imagine yourself taking an immense journey along the entire length of Scotland, on the very spine of the country. The many photographs will give you a tantalising flavour of just some of the magnificent landscapes to be experienced along the way, by hill, mountain, rock, moor and forest. These images may evoke memories of other journeys and from each of these, may also develop a very personal growing love of our wilder landscapes. They may re-kindle your awareness of places not yet visited, but very much on yourwish list. While for the walker they will stimulate a fond recollection of many fine days out on the hill. InNature’s Peace, there is an entirely novel visual experience of a vast swathe of much of Scotland’s best countryside, on an original route from the border with England all the way to Unst in Shetland, by way of Duncansby Head in Caithness. It proudly connects, then presents, and enthusiastically celebrates a large slice of Scotland as you have never quite seen it before.

Stacks of Duncansby

Stacks of Duncansby stand like a guard of honour to mark the inspiring approach to Duncansby Head.

Colin Gregory,Thurso Camera Club

ND397715

Blackwater Reservoir

Light on water and range beyond range – Blackwater Reservoir and Glencoe from Sron Leachd a Chaorainn.

Peter Wright

NN419629

Ben Alisky and Morven

Morven framed by the Watershed’s twin tops of Ben Alisky and Beinn Glas-choire.

Colin Gregory,Thurso Camera Club

ND039387

The recognition and enjoyment of the great Watershed of Scotland offers an opportunity to do something for Scotland, her people and her visitors, of almost unrivalled integrity. It most certainly provides an opportunity to ‘do something for wildness’, as Muir so eloquently invites. As an addition to the gazetteer of Scotland, it creates a radical dimension to how we see and appreciate the landform of this country. For those who love all that Nature has bestowed, and are tuned in to that eternal heartbeat, there is an eco-spiritual enrichment in these special landscapes.

This golden opportunity has a head start, for it already binds a large number of designated and protected sites, and every single national environmental organisation has an active presence. Many local conservation groups have a direct interest intheirlocal landscapes which form an integral part of it. It isScotland United – by Nature, by wildness.

Those who travel around Scotland and appreciate the great landscapes that this country has to offer will in all likelihood have crossed and re-crossed the Watershed on countless occasions, perhaps without even being aware of it. Many writers have drawn attention to that special moment when the traveller willcross the Watershed, almost as a right of passage, perhaps to some other exciting destination elsewhere.

South from Culter Fell

Lone walker and boot-marks in the snow leading south from Culter Fell to Gathersnow Hill and Hillshaw Head.

Anna Woolverton

NT052291

How does this all link together to form the great Watershed of Scotland; indeed, what is this apparently novel geographic feature which has mysteriously appeared? In the United Kingdom the picture is paradoxically sketchy, while north of the border, there are but two historical references, by Francis H. Groome in 1884 and then in the Collins Survey Atlas of Scotland of 1912 – both of which allude to the geographic Watershed. Yet, what we have is an intriguingly simple divide between, on the one hand the Atlantic Ocean and those bodies of water that are directly connected to it, such as the Solway Firth, the Irish Sea and The Minch, while to the east there is just the North Sea.

A small number of intrepid people have now walked and indeed run the Watershed in whole or in part. The first to walk the fully defined geographic Watershed was Malcolm Wylie. Dave Hewitt accomplished an impressive continuous walk along much of the Watershed some years earlier, with a Northern terminus at Cape Wrath – top left-hand corner. The author undertook his backpack Watershed trek in stages in 2005, and in 2012, Colin Meek completed an incredible Watershed run. Chris Townsend will be the most recent with his venture in summer 2013. Others have contributed to this walking genre by undertaking their own version or particular part of it.

This very brief dip into the Watershed on-foot phenomenon is surely beginning to provide a graphic explanation of just what this key landscape feature is. To round it off, however, the concept is indeed a simple one, and a number of people have remarked that it is strange that something so simple has not been more widely promoted and celebrated much sooner.

Eskdalemuir

The enticing upper-Eskdale, with a Watershed source rising to the left of this landscape.

Nancy Chinnery,Eskdalemuir Community Hub

NY243990

So the classic description goes as follows: ‘Imagine that you are a raindrop about to land on Scotland, well your destiny dear raindrop is that when you do touch-down, you will start another journey by bog, burn and river. Finally, you will empty into either the Atlantic Ocean or the North Sea, and which it is to be will depend upon which side of the spine of the country – the Watershed, or water divide – you have first landed’.

The most detailed definition and description of the Watershed of Scotland has been given in the author’s ownRibbon of Wildness – Discovering the Watershed of Scotlandpublished by Luath Press in 2010. The Royal Scottish Geographical Society in response to this, in 2011, described the Watershed as ‘this hitherto largely unknown geographic feature’. WhilstThe Scotsmanhad this to say:‘No other journey can give so sublime a sense of unity, a feeling of how the Nation’s various landscapes link together to form a coherent whole’. Clearly public awareness is changing year on year, and there can be no more fitting events than the Year of Natural Scotland in 2013 and John Muir Centenary during 2014 to ensure that the Watershed of Scotland is more widely and popularly appreciated – simply for what it is.

Black Law Wind farm

Desirable or destructive – the dilemma of turbines on the Watershed, and Black Law.

Peter Wright

NS910550

Ben Alder

Snow and mist remnants on the hill – Ben Alder from Sgor Gaibhre, over Beinn a Chumhainn.

Richard Kermode

NN469718

Cadha Dearg

Pause to ponder the Gleann a Cadha Dearg with the distinctive Coigach beyond.

Colin Meek

NH283861

Quinag from Glas Bheinn

Lochan Bealach Cornaidh nestles in the lee of Quinag and Sail Gharbh, viewed from Glas Bhein.

Nick McLaren,Lairg Learning Centre

NC255264

Ben Hee

Summit rocks and crags of Ben Hee with Loch Naver and Ben Klibreck, to the east.

Chris Townsend

NC426339

This does of course beg the question as to why the Watershed should be of such growing importance, and from this, why should it be valued in a way that has not been the case hitherto?

We have of course, a bit of catching up to do with other countries and continents, where the key place and function of the Watershed in their respective landforms is fully appreciated, celebrated even. We have the growing range of hard copy and online accounts of the on foot journeys along all or part of the Watershed, and these are nothing if not inspiring. Indeed, the common thread is that theroutewas created not by mankind; not in any way for our convenience, but solely by the hand of Nature. There are a growing body of people who are fascinated by the immensity of the forces, timescales, events, and processes that have given us this Watershed, and put it where it is. It is certainly largely unchanged in location, since the end of the last Ice Age, while many parts of it extend much further back into geo-glacial time. True, its surface and habitat character have changed greatly over these thousands and millions of years, but location and where water starts its further journey by bog, via burn and river,is largely unaltered.

Blar nam Faoileag Sunset

Winter sunset catchingan extensive area of Flows, from above Blar nam Faoileag, to Morven.

Norrie Russel, RSPB Forsinard

ND131453

This alone, however, will not suffice as a reason for conservation; the historical dimension is only a part of the story. Much has rightly been done of late to identify, describe and give critical importance to wild land, and to mark out the value of wildness in our landscapes. There will be those who argue thatwild landandwildnessmay not necessarily be one and the same thing, and they may produce factors which set them apart. The processes and methods of defining wild-land may be emerging as a more exact science, but the areas thus defined are sadly shrinking – both on account of increasing precision in the criteria being used and of the inexorable encroachment into these very areas, by man-made structures. Most are naturally far from the main centres of population, and herein lies both a dilemma and a challenge. These areas are unquestionably worth greater protection, but their very remoteness, often at the extremity or boundary of both estate and local authority, serve to marginalise their priority. They are however something well worth arguing for.

After the Snow Flurry – Borders Hills

Texture of light catching snow covered tussocks, under a heavy sky in the Border Hills.

Peter Wright

NT558019

Bodesbeck Law

Lochan on the edge of the deep steep crags on Black Hope to the inviting Bodesbeck Law, with Mirk Side on the left.

Anna Woolverton

NT169104

The meaning of the relative concept ofwildnessmay have changed subtly since Muir’s day, but in a way that it is argued, demands a more inclusive approach; it surely implies something with immense, almost unlimited potential – for people. It is something which we can all engage with, something which invites participation; something from which we can all draw strength and renewal.

Lochcraig Head

Evidence of a severe cold-spell with ice-encrusted post on Lochcraig Head.

Keith Brame

NT167176

White Hill Cloud Inversion

Island of woodland in a cloud inversion east of White Hill above Dolphinton.

Peter Wright

NT089469

Wildness and weather are certainly closely related. Any notion that the Watershed bathes in never-ending sunshine, no matter how appealing all of the pictures in this book are, would be misleading. To illustrate this point, the author cites his own experience throughout much of his trek in 2005. Of the 64 days of walking, the visibility was poor for around one third of the time, and on just two of these days the weather was also marred by torrential rain and wind. Not a bad record in fact. But it should be remembered that with an average elevation of some 470m, parts of it are inevitably shrouded in mist, but that is one of the tantalising qualities of the outdoor experience – unpredictability.

It would indeed be intriguing to be able to welcome John Muir back to the land of his birth, and to see what he would make of it today. The John Muir Trust is the worthy and effective custodian of his legacy. The very least that we can do is to actively support this organisation in all that it does. We can be sure that there is much in both the theme and landscape character described here inNature’s Peacethat Muir would have commented upon had it been possible, and we can only speculate on what he might have said to us. It would not be unreasonable therefore to imagine a virtual visit, and to posit his verdict on the Watershed at least, towards the end of this book.

Forth and Clyde Canal

Cycling in the sun beside the Forth and Clyde Canal eastof Kelvinhead.