Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

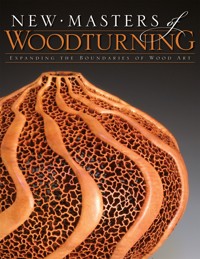

MEET THIRTY-ONE CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES OF A CLASSIC CRAFT.They are from different parts of the world but share a common passion: turning wood into sculptural forms of self-expression. You'll see each artist at work--in their studios, homes, and at the lathe--and discover why their stunning work is considered to be preeminent in the respective fields of woodtruning and modern art. A gallery of beautiful photographs is included. New Masters of Woodturning looks beyond the surface of the wood and into the vision and mind of the artist, providing insights that offer a captivating and important perspective of turn-of-the-century art and craft.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 262

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

© 2008 by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.

New Masters of Woodturning is an original work, first published in 2008by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.

eISBN 978-1-60765-097-3

ISBN 978-1-56523-375-1 (cloth); 978-1-56523-334-8 (pbk.)

Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Martin, Terry, 1947-

New masters of woodturning : expanding the boundaries of wood art

/ Terry Martin & Kevin Wallace. -- East Petersburg, PA : Fox Chapel

Publishing, c2008.

p. : ill. ; cm.

ISBN: 978-1-56523-375-1 (cloth) ; 978-1-56523-334-8 (pbk.)

1. Woodworkers--Biography. 2. Turning--Technique.

3.Woodwork. I. Wallace, Kevin. II. Title.

TT201 .M37 2008

684.08/3--dc22 0806

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

Note to Authors: We are always looking for talented authors to write new books in our area of woodworking, design, and related crafts. Please send a brief letter describing your idea to Peg Couch, Acquisition Editor, 1970 Broad Street, East Petersburg, PA 17520.

eBook version 1.0

Because working with wood and other materials inherently includes the risk of injury and damage, this book cannot guarantee performing the activities in this book is safe for everyone. For this reason, this book is sold without warranties or guarantees of any kind, expressed or implied, and the publisher and the author disclaim any liability for any injuries, losses, or damages caused in any way by the content of this book or the reader’s use of the tools needed to complete the projects presented here. The publisher and the author urge all woodworkers to thoroughly review each project and to understand the use of all tools before beginning any project.

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to the memory of Dona Z. Meilach, who saw wood art for what it was before any of us.

Alan Giagnocavo

President

J. McCrary

Publisher

Peg Couch

Acquisition Editor

John KelseyPaul Hambke

Editors

Troy Thorne

Creative Direction

Lindsay Hess

Design

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Terry Martin is a wood artist, curator, and commentator on wood art. During the last twenty years, he has taken part in 80 exhibitions in seven countries and his work is part of many of the large private and public collections devoted to wood art. Martin was the author of Wood Dreaming, published in 1995, the only book ever produced on Australian woodturning. Martin has written more than 200 articles on wood art published in twelve journals in seven countries.

From 1999 to 2006, Martin was editor-in-chief of the woodturning journal Turning Points, the only journal dedicated solely to wood art. Martin also is a contributing editor to Woodwork magazine and writes for several other publications around the world. His greatest pleasure is writing about people he respects. Martin has written hundreds of articles dedicated to showing the world the amazing things people do with wood.

Kevin Wallace is an independent curator and writer, focusing on contemporary art in craft media. He has guest-curated exhibitions for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Craft and Folk Art Museum, Los Angeles; the Long Beach Museum of Art; the Cultural Affairs Department of Los Angeles; Los Angeles International Airport; the San Luis Obispo Art Center; and the Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts. He has previously curated two exhibitions for the Long Beach Museum of Art: Into The Woods and Transforming Vision: The Wood Sculpture of William Hunter, 1970-2005.

Wallace is a member of the Board of Directors of Collectors of Wood Art and on the Advisory Board of the Handweavers Guild of America. He is a contributing editor for American Woodturner and Shuttle, Spindle & Dyepot and a regular contributor to Craft Arts International (Australia) and Woodturning Magazine (England), writing about contemporary art in craft media (wood, ceramic, and fiber) and wood artists. Wallace serves on the Board of Directors of Collectors of Wood Art (CWA) and on the Advisory Board of the Handweavers Guild of America.

Wallace is the author of seven previous books: River of Destiny: The Life and Work of Binh Pho, 2006; Transforming Vision: The Wood Sculpture of William Hunter, 2005; The Art of Vivika and Otto Heino, 2004; Celebrating Nature–Craft Traditions/Contemporary Expressions, 2003; Contemporary Glass: Color, Light and Form, (with Ray Leier and Jan Peters), 2001; Baskets: Tradition & Beyond, (with Leier and Peters), 2000, and Contemporary Turned Wood: New Perspectives in a Rich Tradition, (with Leier and Peters), 1999.

ABOUTNEW MASTERS OF WOODTURNING

Since Dale Nish wrote Master Woodturners (1986), the field of woodturning has grown immensely. The artists featured in New Masters of Woodturning create a range of technically and aesthetically challenging works that push the boundaries of craft and art. New Masters of Woodturning offers a unique, international perspective. The book brings together artists from countries where the field of creative turning has taken root. The artists share their personal motivations, thought processes, and studio techniques. The many photographs show them at home and in their studios, and illustrate many of the techniques they employ.

New Masters of Woodturning presents a wealth of approaches, techniques, and philosophies of woodturning. The book explores the influence of other leading woodturners and offers a historical perspective. Many of the artists have been influenced by other disciplines, including architecture, sculpture, literature and indigenous art, as well as the ever-present power of nature.

The book will be of interest to every woodturner and others working in wood who have an interest in self-expression, sculpture and the decorative arts. The book will serve as an important document of turn-of-the-century arts and craft, bringing contemporary woodturning to a larger audience. As the book concerns thought and process, it will be of interest to artists in a range of media, as well as collectors of art and craft.

Louise Hibbert, Salt and Pepper Mills, collaboration with Sarah Parker-Eaton, 2003. English sycamore, silver, resin, acrylic inks, and ceramic mechanism. This set of salt and pepper mills is a fine example of production woodturning. For more of Hibbert’s work, see page 145.

Photo courtesy the artist

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

LIAM FLYNN: Striving to Find the Perfect Line

HAYLEY SMITH: Ideas Evolve and Flow into the Next Piece

J. PAUL FENNELL: Technical and Creative Challenges Are Always Mingled

HARVEY FEIN: Consider Texture, Pattern, and Inclusions

BUTCH SMUTS: Keeping It Simple Is the Best Investment

RON FLEMING: More Ideas Than I Can Ever Produce

PETER HROMEK: You Find These Shapes Everywhere in Nature

WILLIAM MOORE: The Contrasting Relationships of Wood and Metal

VAUGHN RICHMOND: Technical Challenges Are the Most Exciting

ROLLY MUNRO: The Lathe Creates Armatures for Major Sculptural Work

HANS WEISSFLOG: Totally Focused While Turning

JACQUES VESERY: When I Get in a Groove, Watch Out

MICHAEL HOSALUK: I’m Not Afraid to Venture Out of My Comfort Zone

MICHAEL MODE: The Intimate Interplay of Idea, Hand, and Eye

DEWEY GARRETT: The Lathe Places a Limit, Yet Offers Endless Possibilities

BETTY SCARPINO: It’s Like Discovering Hidden Treasure

CHRISTOPHE NANCEY: A Symbolic Picture of the Living Process

VIRGINIA DOTSON: Shaping Layered Wood Reveals Compositions of Patterns

RON LAYPORT: Surface Work Will Not Cover Up Poor Form

NEIL SCOBIE: Thinking of Running Water

MARK GARDNER: Drawn to the Rhythm of Repeated Carved Patterns

MARILYN CAMPBELL: Pushing the Designs While Keeping Them Simple

STEVEN KENNARD: Technique Is Important, But Secondary to Getting There

LOUISE HIBBERT: The Lathe Gives My Work Rhythm and Balance

THIERRY MARTENON: It’s Good to Work with Almost Nothing

GRAEME PRIDDLE: Pacific Island Culture and the Ocean’s Beauty

BINH PHO: Stories Told with Color

MARC RICOURT: The Vessel Was Mankind’s First Tool

MIKE LEE: Wood Is a Joy To Work or My Worst Nightmare

ALAIN MAILLAND: There Is No Limit to the Forms I Can Make

DAVID SENGEL: Much Yet to Do with the Lathe

GLOSSARY

LIST OF ORGANIZATIONS

FURTHER READING

COVER

J. Paul Fennell, De la Mer (Of the Sea), 2007. African sumac, 9″ high x 11¼″ diameter. For more of Fennell’s work, see page 13. Photo courtesy the artist.

TITLE PAGE

Marc Ricourt, Vessel, 2005. Walnut, ferrous oxide, 25″ x 9″ diameter. Ricourt’s work resembles rusted iron, or ancient pottery. For more of Ricourt’s work, see page 169.

INTRODUCTION

Woodturning in the 21st Century

During the 1960s and ’70s, turned wooden bowls first came to be considered as objects of contemplation rather than simply of function. An art-like market gradually developed among collectors who considered such bowls too beautiful to use. Turners of vision started to ignore tradition, and to make pieces that broke many of the old “rules” of the craft. It was a quiet revolution, but a strangely disconnected one, because many participants had no idea what the others were doing. If anyone read about woodturning, it would have been in books emphasizing the trade values of techniques, not of innovative shapes or aesthetics.

In 1976, the American writer Dona Z. Meilach first documented the work for what it was—the beginning of a new art movement. In her book, Creating Small Wood Objects as Functional Sculpture, Meilach assembled much previously scattered history and put it into a larger context. She was probably the first person to describe turning as “sculptural” and to refer to turners as “artists.” Meilach also introduced people who would shape the new field, such as Melvin Lindquist, Bob Stocksdale and Canada’s Stephen Hogbin (page x). Meilach’s work alerted many artists to the fact that there were others like them, and also inspired many newcomers to join the movement. Meilach continued publishing insightful books on the fields of wood art and general craft, more than 100 in all, until her death in late 2006.

During the 1970s and into the ’80s, the then-new Fine Woodworking magazine published a series of articles that reached an enormous audience around the world and changed the future of turning forever. The series included stories on turning delicate bowls of exotic timber by Bob Stocksdale; heavily spalted wood, previously unheard of, by Mark Lindquist; green turning, a technique practiced by turners for hundreds of years, by Alan Stirt; inlaid wood with hi-tech finishes by Giles Gilson, and, most significant of all, a 1979 article by David Ellsworth (page xi) on hollow turning. Ellsworth laid down his challenge to the turning world: “Bowl turning is one of the oldest crafts. It is also among the least developed as a contemporary art form.” Ellsworth was good at explaining the technical aspects of his work—lathe specifications, speed, tools—but he also introduced language and a philosophy that had never before been heard in relation to turning: “The concentration involves all senses equally, and the center of focus is transferred to the tip of the tool.” It was heady stuff, just right for the times, and it hit the mark in a culture ready for rule-breakers.

In 1980, Dale Nish of Provo, Utah, published the milestone book Artistic Woodturning. Nish showed foresight when he put the word artistic on the cover and he introduced ideas that profoundly influenced turners around the world. Nish spoke of paying “tribute to nature’s designs,” and of making the most of faults and damage in wood. Nish was one of the first to chronicle the changing ways turners were using wood, and their new approaches to displaying its beauty.

Ron Fleming, Yama Yuri, 2006. Basswood, acrylics; 36″ high x 17″ diameter. Fleming created the turned vase as a vehicle for the painted lilies, which are life-size. He says, “I had to reinvent the air-brush process to be able to apply the frisket on a curved surface. There’s more than 400 hours in it.” For more of Fleming’s work, see page 31.

Photo courtesy the artist

Nish followed up in 1985 with Master Woodturners, featuring the work of nine artists who, if they were not already, were transformed into turning icons: the Americans David Ellsworth, Mark Lindquist, Ed Moulthrop, Rude Osolnik, Al Stirt, and Jack Straka, along with England’s Ray Key and Australia’s Richard Raffan. The inclusion of the latter two was an early indication the new field was becoming an international phenomenon. In 1985, The Taunton Press published Turning Wood, the first of Raffan’s widely sold series of how-to books and videos, which many artists today cite as a valuable part of their education.

Other turners who were repeatedly acknowledged as mentors and exemplars in interviews for this book include David Pye, Del Stubbs, Bob Stocksdale, Michael Hosaluk, Al Stirt, John Jordan, Jean-Francois Escoulen, and Mike Scott. It is impossible to give credit to all of those who deserve it, yet it is worthwhile mentioning the reputations of some woodturners have been compounded by repetition during the last thirty years, while many equally deserving names have been passed over. Like any field of endeavor, creative woodturning has a history filled with anonymous and forgotten contributors.

STEPHEN HOGBIN: BREAKING OUT OF ROUNDNESS

Stephen Hogbin was born and educated in England, then immigrated to Canada in 1968, to teach design. In 1974, he astonished the craft world with an audacious exhibition timed to coincide with a World Craft Congress meeting being held in Toronto that year. Hogbin was, perhaps more than any other person, responsible for upsetting the tyranny of the circular form that had dominated the turning world for thousands of years.

Stephen Hogbin’s 1974 Toronto exhibition astounded woodturners and the larger craft world alike. As the woodturning writer and educator Mark Sfirri has said, “Hogbin was 20 years ahead of his time, and now, 30 years later, he is still 20 years ahead of his time.”

Hogbin’s first book, Woodturning: The Purpose of the Object, was published in the mid-1970s and shattered many preconceptions about materials and techniques. As Steven Kennard (page 139) said, “It really opened a door, as this idea was so new to me—that something which primarily makes round objects could be used to produce sculptural pieces that left you wondering how they were created.” Hogbin showed the way for the many artists who would later cut, rejoin, color, combine materials, and bend the rules. Marilyn Campbell (page 133) said, simply, “He showed me turning could be art.”

David Ellsworth, right, presents the American Association of Woodturners lifetime achievement award to Mark Lindquist, left, and Stephen Hogbin, center, at the AAW’s 2007 conference. Photo by John Kelsey.

A New Collector

The new work attracted a new kind of collector, people who not only fell in love with the lure of wood, but also believed the leading woodturners could become the new art stars. It was not to be the case. If the new turning heroes became famous, it was not in the broader art field, but among the legion of aspiring turners with lathes in their garages who sought to create similar work. The amateur artisans formed a new market for tools and hardware, and for a time each new turning idea generated a new line of equipment. From sophisticated hollowing systems to ever-larger lathes, vast numbers of tools were manufactured and sold to the burgeoning amateur market. As a result, a thin and difficult-to-navigate line developed between amateurs who were able to create technically proficient work, largely by imitating or taking classes from their heroes, and those who had a distinctly original aesthetic vision that propelled the field forward.

Very early on, a small group of woodturners emerged as the collectible masters. The group included James Prestini, Bob Stocksdale, Melvin and Mark Lindquist, Rude Osolnik, and Ed Moulthrop. As the field expanded during the 1980s and ’90s, new artists entered the gallery system, among them such innovators as Todd Hoyer, Stoney Lamar, Michael Peterson, Giles Gilson, John Jordan, Mike Scott, and Michelle Holzapfel. The infusion created challenges for new collectors and curators, who had to navigate a scene where accomplished artists exhibited alongside emergent novices. The early success of the true innovators suggested originality was the key to sales, so the new generation began to create ever more unusual and technically complex work. At the same time, some who had already made their mark by creating original work seemed condemned to repeat their ideas incessantly, to satisfy the desire of collectors to own a signature piece.

DAVID ELLSWORTH: HOLLOW LIKE AN EGGSHELL

Ellsworth came to broad notice in 1979 when Fine Woodworking magazine introduced his techniques for hollowing wood through narrow openings to create vessels more like pottery than any woodwork that had gone before. His work overturned all of the deeply held traditions of functionality that had defined turning. Ellsworth himself was profoundly influenced by Native American pottery, and he planted the seeds for the explosion of creative woodturning that was to follow. For the first time, woodturners were seeing themselves as artists.

David Ellsworth astounded the woodworking world with his 1979 magazine account of his hollow-turning techniques, combined with his perspective on where his work fit in the larger craft/art world.

Ellsworth went on to help found the American Association of Woodturners, serving several terms as its president. He continues to produce his astonishing hollow-turned turned vessels at his studio in Quakertown, Pennsylvania, where he also teaches weekend seminars and manufactures his own line of tools for hollow turning.

David Ellsworth, Ovoid Pot #1, spalted sugar maple, 6″ high x 11″ diameter. His pieces combine the fluid lightness and elegant form of pottery with the beautiful figure and texture of wood.

RICHARD RAFFAN: GOOD TECHNIQUE AND GOOD DESIGN

Richard Raffan often is acknowledged for demystifying the very ancient craft of turning, showing how almost anyone could achieve superb results using simple tools and techniques. A turner since 1970, Raffan published the first of his series of how-to books, Turning Wood with Richard Raffan (Taunton Press), in 1985. Since then, he has traveled tirelessly as a demonstrator and teacher, in the process emigrating from England to Eastern Australia. He is perhaps the person most responsible for spreading the idea that anyone can learn to turn wood. Raffan always has emphasized the need for good line and simplicity of design, and recognizes the generations of British production turners who went before him. In his own words, “I don’t feel the need to be different, but I would like to be good.” As the German turner Peter Hromek (page 37) said, “I found a translation of Richard Raffan’s book on woodturning design and it became my bible.”

Many thousands of woodturners have learned basic skills by imitating Richard Raffan, via his many books, videos, and DVDs.

Richard Raffan, Bowl (production work). Oak, 16″ diameter. Raffan’s appeal lies in his no-nonsense combination of professionally efficient techniques with an excellent, and explainable, sense of design. Photo courtesy the artist.

Round No More

Woodturning is unlike other traditional woodcrafts. In carving, furniture making, and carpentry, one takes pains to hold the wood still so it can be worked by moving tools. In woodturning, the lathe rotates the wood itself against a hand-guided tool. The inversion has two valuable consequences: much turned work can be completed right on the lathe with no additional processing, and woodturning offers a very quick path from fallen tree to finished object. It also brings a limitation formerly seen as inviolate: turned work is round.

Much of the wood art in this book inverts those truisms: the lathe is merely the beginning, with additional off-lathe processing to come. It is not at all quick, and it no longer has to be round.

Most of the early innovators made their work entirely on the lathe and the artists in the book generally started out doing the same. Most of them spent many years mastering the traditional skills of turning before feeling the need to add other techniques. Many don’t use the lathe nearly as much now, and some struggle with whether they are “turners” at all. A piece of wood might spend a very brief time on the lathe, followed by months of reworking, sometimes removing or concealing any evidence it was initially turned. The trend in turned wood art now is to carve, burn, paint, recut, and rework pieces.

Once woodturning was valued for how quickly and inexpensively it could be done, but now artists boast of how many months they spend reworking a piece after turning it. However, many say their work is still “defined by the lathe” and most admit to a deep-seated love of the very ancient craft of turning. It is true that even when a piece has been reworked extensively, its beginnings as a round and symmetrical shape still will show through—its lines are too powerful to entirely disguise. The artists’ loyalty to the lathe may seem surprising, however, because it is the work they do after turning that makes their work distinctly their own.

Perhaps the contradictions of turned wood art are best summarized by Vaughn Richmond (page 51) when he says, “Some of my woodturning may have an element of sculpture, and some of my sculptures may have an element of woodturning.” At the same time, many wood artists simply define their work as turning. Hans Weissflog (page 63), the only turner in this book to have completed a traditional turning apprenticeship, is in no doubt about the importance of the lathe: “I believe the lathe provides more possibilities than most people know. That’s what I want to show in my designs, as it is my most important tool.”

The beauty of wood is what attracts many artists in the first place, and much early work celebrates it. It is about the wood’s appearance, smell, grain, texture, and links with the natural world. In the early days, a clever use of wood grain was enough to claim artistry. Even now, when artists may obscure the wood by texturing, burning, and painting, it still has appeal in its warmth, heft, and vitality. Christophe Nancey (page 103) puts it well: “I see the wood as my first tool and my first source of inspiration.”

For many of the artists in this book, their immediate environment is another important part of who they are and what they create, and pursuing a solitary craft with an uncertain income is their method for being able to live in places they love.

Michael Hosaluk’s colors are much admired. See page 75.

Photo by Grant Kernan

Binh Pho’s work is unbelievably intricate. See page 163.

Photo courtesy the artist

Exciting New Techniques

For a long time, many who were promoting wood art liked to compare it to ceramics and art glass. They were looking for a vocabulary to help build credibility in the top-end market. In reality, contemporary wood art uses techniques as exciting as anything being done in other fields. Burning the wood has progressed from rough blowtorching to refined finishing and patterning, such as the delicate burnt textures of Graeme Priddle (page 157). Texturing has expanded to include everything from the controlled brutality of Marc Ricourt’s slashed finishes (pages ii and 169) to the delicacy of carved surfaces by Jacques Vesery (page 69) or Liam Flynn (page 1). Where painting and color once were treated with suspicion, the playful use of color by Michael Hosaluk (page 75) and others now is much admired. Much of Ron Fleming’s work depends upon his skills as an illustrator (pages viii and 31), while Binh Pho’s pieces (page 163) are more about color and carving than anyone in the early days could have imagined. Once wood was the sacrosanct material, but now it’s complemented by other materials, such as the spun metal of William Moore (page 45). If anyone doubts turned wood art is now as much about carving, texturing, and sanding as it is about turning, they only have to look at the astonishing work of Alain Mailland (page 181). One day, wood art will be recognized for the repertoire of techniques and processes it has fostered.

William Moore mates metal and wood. Detail, Equilibrium, see page 45.

Photo by Dan Kvitka

While turned wood art has its roots in utility, today’s artists often encounter a prejudice against function. Galleries, collectors, and museum curators tend to frown upon production work and functional bowls, suggesting those woodturners will not be accepted as “serious artists.” However, many woodturners continue to produce functional multiples as a means of supporting their families and because they simply enjoy the work. Louise Hibbert (pages vi and 145) believes utilitarian work still is important. “Repeating forms keeps my turning skills up to speed,” she says. “I love my living environment to be filled with useful things, hand made with care and filled with personal significance. Its a sad fact that hand-made functional items, imbued with individuality, are seen as less valuable than sculptural pieces.”

Liam Flynn repeats fine patterns across subtly figured wood. Detail, Untitled (2006), see page 2.

Photo courtesy the artist

Jacques Vesery carves and paints tiny, delicate creatures. See page 69.

Photo courtesy the artist

Graeme Priddle patterns the wood by charring it. Detail, Tahi Rua (One Two), see page 157.

Photo courtesy the artist

From ancient and humble beginnings, woodturning has been transformed into an art form for the twenty-first century. As both wood and fine craftsmanship become more precious in a machine-made world, the art not only reminds us of a simpler past, but it also shows nothing is fixed and old skills can evolve unexpectedly. The artists in this book acknowledge their predecessors, both ancient and more recent. In turn, we hope the work in these pages will inspire others to grow in new directions.

By featuring the work of fourteen Americans, two Australians, three Canadians, one Irishman, two New Zealanders, one South African, four Frenchmen, two Germans, and two Britons, this book shows the international flavor of the contemporary turning movement. The turning renaissance coincided with the rise of the Internet and niche publications, so more information about new ideas and techniques probably has been exchanged during the last twenty years than in the previous 2,000 years. The popularity of seminars and club demonstrations has increased exponentially and now some turners travel internationally for much of each year in the northern and southern hemispheres, teaching, demonstrating, and acting as turning ambassadors.

The authors are responsible for choosing the artists represented here, but after that, we have tried to let the artists speak for themselves. It is their world and they know it best. One inspiring aspect of their world has been the willingness of everyone to share their ideas, techniques, and joy in what they do. While there are distinct differences in how people work, there are no trade secrets. We are fortunate the woodturners in this book have shared their lives so freely with us and our sincere thanks go out to them.

—Terry Martin, Brisbane, Australia, and Kevin Wallace, Los Angeles, CA.

LIAM FLYNN

Striving to Find the Perfect Line

Woodturning has a venerable history in Ireland, where the oldest finds of turned wooden bowls date back around 2,000 years. For most of that time, the wares made on the lathe were traditional functional items, such as bowls and ladles.

Liam Flynn is a modern Irish turner in every sense, including his use of traditional oak for many of his projects. Unlike his predecessors, though, Flynn designs his work not to be used. Once he has ebonized the finished work, it has a deep patina that evokes ancient vessels blackened by their long slumber in the peat bog of archaeological sites.

Flynn’s plans for his life didn’t initially include becoming a turner, though a future in woodworking always was likely. “My family has been involved in woodworking for generations. I was working with wood as far back as I can remember and I started out making very basic furniture,” he explains.

I dislike ‘stunning wood grain’ in the traditional sense. I prefer a plain canvas.

Untitled, 2006. Ebonized oak; 13″ high x 7½″ diameter. A beautiful example of finely controlled surface carving. The shaped rim is more interesting than a straight rim.

Photo courtesy the artist

Flynn finds it hard to remember exactly why he became a turner. “It’s kind of difficult to find a reason—It just happened!” He explains that in 1982, he purchased John Makepeace’s The Woodwork Book, which featured woodturners Richard Raffan (page xii) and Bob Stocksdale. Flynn was very taken by their work. “It was my first introduction to what was possible on the lathe,” Flynn says. The book also contained an essay entitled, “Making Your Work Your Own,” by furniture maker James Krenov. “He got me thinking about, as he puts it, ‘…the fingerprints on the object of the person who made it.’ I found I agreed with his belief that the process is so important.”

Shavings fly off the unseasoned wet wood like peelings from a ripe apple. The wood is soft, almost malleable, and yields quickly to Flynn’s sharp tools.

Photo by Brendan Leahy

Untitled, 2006, Fumed oak; 7½″ high x 10″ diameter. Fuming with ammonia gives the piece its soft brown color, while allowing the rays in the wood to flash across the carved flutes.

Photo courtesy the artist

Untitled, 2006. Holly; 6″ diameter. The white holly wood in a delicate piece contrasts wonderfully with Flynn’s ebonized pieces.

Photo courtesy the artist

The distortion that takes place during the drying process is a significant part of my work.

Soon after David Ellsworth astonished the turning world with his hollow vessels (page xi), they became commonplace because of imitators. The fashion for surface decoration arose because vessel makers were trying to distinguish their work from the mass of look-alikes. However, a well-formed simple vase shape remains one of the most impressive things that can be produced wholly on the lathe. A few dedicated professionals have continued to devote themselves to such work, and Flynn is one of the best. His use of plain wood, usually blackened, means his shapes have to be perfect and he succeeds wonderfully. Also, when he decorates the surface of his vessels, it is not for the sake of novelty, but to enhance and emphasize the simple qualities of his elegant forms. Flynn is a modern master of the neo-classical wooden vessel.

Untitled, 2006. Ebonized oak; 5″ high x 9″ diameter. The turned form is symmetrical but the surface carving is offset, giving the ebonized piece of oak a distinct character.

Photo courtesy the artist

Still Life with Holly, 2007. Holly; 13½″ wide. The delicately flaring bowl in white holly contrasts with the strongly enclosed form of its partner vessel. One is filled with light, the other with shadow.

Photo courtesy the artist