79,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Stämpfli Verlag

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

"Time to Leave Law-Law Land ... and Head Back Into the Jungle" Fuelled by advancing technology, new business models, and altered client expectations, the legal industry faces unprecedented change across its entire value chain. Unfortunately, many legal professionals fear the technology train and the convergence of other fields with law. They see legaltech, AI, and bots like "lions and tigers and bears oh my." We (the curators and authors of this book) see opportunity. Although the future may require us to put on "new suits"—it represents an enormous opportunity for lawyers to reinvent ourselves for our own and our clients' benefit. Filled with chapters written by experts in the intersection of law, innovation, and technology, this book provides a global perspective on the diverse legal service delivery ecosystem that will be our future. It provides chapter upon chapter (reason upon reason) explaining why lawyers can and should increase their appetite for disruption in the legal world. So welcome to the jungle and enjoy the ride as we attempt to systematically map the uncharted waters of the future legal realm and simultaneously inspire you to build a new future in law. Endorsements "The 'Artist Formerly Known as the Legal Profession' isn't what it used to be. You think that you know law firms and the challenges that confront lawyers, but you don't. Legal services providers have spent years resisting change, and now seem determined to pack fifty- or sixty-years of evolution into five. The entire legal services market has been transformed by LegalTech, globalization, and new delivery models – and until now there has been no guide to the way that consumers can benefit and providers can profit from the changes. Guenther and Michele have gathered a Who's Who of thinkers to provide a marvellous range of visions of the way that law is changing. They provide a roadmap for the future of law – if only you'll follow it." Professor Dan Hunter PhD FAAL, Foundation Dean, Swinburne Law School "'Nomen est omen' if you read the book title of 'New Suits'. It encourages, allows and requests lawyers at all levels to rethink their former and existing ways of doing business in many areas of law. In the same, it outlines great opportunities to a new breed of experts in our profession. Thanks to the various authors, one gets a good understanding of how massive the impact of technology has become – and is going to be - to the legal services market. And the authors provide a distinct view of how a rather traditional profession will have to transform their business models to comply with the fast changes in the marketplace." Jürg Birri, Partner / Global Head of KPMG's Legal "For a while now, we have been hearing about digitization, disruption and new delivery models in the world of Big Law. "New Suits" both reassures and gives a wake-up call to all of us in the business of providing legal services. Setting out both the opportunities and the threats engendered by the dynamic change in our industry, the book is an invaluable guide to all lawyers and legal business professionals wanting some insight on the challenges facing them in a globalized and accelerating world." Dr Mattias Lichtblau, CMS "This book comes at a time where we see just the beginning of a transformational change on the legal market. While such transformation is seen as a great opportunity for those participants who endorse change and innovations, others seem to be more frightened by potential disruption of their well-established business models. The structure and comprehensive contributor listing for this book encapsulates many disparate challenges faced by almost all players on the market. The lecture of the book should give good guidance to anyone who is interested in how the legal profession is (finally) modernizing, capitalizing on technology trends and becoming more client-centric.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 1328

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Prelims

Front cover

Fuelled by advancing technology, new business models, and altered client expectations, the legal industry faces unprecedented change across its entire value chain. Unfortunately, many legal professionals fear the technology train and the convergence of other fields with law. They see LegalTech, AI, and bots like «lions and tigers and bears oh my.» We (the curators and authors of this book) see opportunity. Although the future may require us to put on «New Suits»—it represents an enormous opportunity for lawyers to reinvent ourselves for our own and our clients’ benefit. Filled with chapters written by experts in the intersection of law, innovation, and technology, this book provides a global perspective on the diverse legal service delivery ecosystem that will be our future. It provides chapter upon chapter (reason upon reason) explaining why lawyers can and should increase their appetite for disruption in the legal world. So, welcome to the jungle and enjoy the ride as we attempt to collaboratively map the uncharted waters of the future legal realm and simultaneously inspire a new future in law.

Praise for «New Suits»

«To lead change, it is critical to engage emotion, find common purpose and build a sense of urgency. With New Suits, two of the brightest, energetic and creative leaders in the world of legal innovation, Guenther Dobrauz and Michele DeStefano, generously provide legal leaders with the frameworks, data and perspectives they need to build the case for change NOW. By engaging a diverse, cutting-edge team of contributors to New Suits, Guenther and Michele practice, too, what they preach—teamwork and a rigorous, interdisciplinary approach to solving problems. I’m now ready for my New Suit!»

– Professor Scott A Westfahl, Professor of Practise & Director Executive Education, Harvard Law School«Those of us interested and involved in today’s rapidly changing world of legal services delivery have in recent years had plenty of go-to sources to whet our appetites on the topic. But never before has there been in the «legal world» such an elucidation of the «appetite for disruption» as brought to us by Michele DeStefano and Guenther Dobrauz in their new book. The breadth and depth of the history, in theory and in practice, and the future of legal services transformation one finds in «New Suits» is both welcome and exceptional. It will no doubt be widely referred to by general counsels and outside counsel often and extensively as we all continue this interesting journey into the era of the digital lawyer.»

– William Deckelmann, General Counsel, DXC Technology«Lawyers will likely always be lawyers. But the way they work will change fundamentally—to their own and their clients’ benefit. Also, we expect a fundamental re-definition of what constitutes actual legal and in particular lawyers’ work and what is adjacent and accessory. All of the latter will surely be impacted by technology and other solutions and also the core of our business will face disruption. Michele and Guenther—two recognized legal rebels—have been at the forefront of all of these developments for several years now and have brought together an amazing group of authors to map the current state of the industry and to provide insight into what the future may hold.»

– Professor Dr Heinz-Klaus Kroppen, Global Legal Leader PwC«The «Artist Formerly Known as the Legal Profession» isn’t what it used to be. You think that you know law firms and the challenges that confront lawyers, but you don’t. Legal services providers have spent years resisting change, and now seem determined to pack fifty- or sixty-years of evolution into five. The entire legal services market has been transformed by LegalTech, globalization, and new delivery models—and, until now, there has been no guide to the way that consumers can benefit and providers can profit from the changes. Guenther and Michele have gathered a Who’s Who of thinkers to provide a marvelous range of visions of the way that law is changing. They provide a roadmap for the future of law—if only you’ll follow it.»

– Professor Dan Hunter PhD FAAL, Foundation Dean, Swinburne Law School«Lawyers have been trained to look backwards, to precedent, to find the solutions to their client’s problems. So it should come as no surprise that the profession is «stuck» when it comes to adapting to technology and the need to understand its transformational impact on the future of legal practice as we know it. This book not only helps the reticent among us better understand why they can no longer stand on the sidelines and hope they finish their careers before being forced to change how they practice, but also gives comfort that client service and satisfaction will improve significantly with its adoption. «New Suits» not only provides the step by step to get to acceptance, adoption and successful implementation of new legal technology, but also helps the reader overcome their fear that the profession’s transformation must be seen in a negative light, rather then a unique opportunity for growth.»

– Hilarie Bass, Former President American Bar Association and President & Founder at Bass Institute for Diversity and Inclusion«For a while now, we have been hearing about digitization, disruption and new delivery models in the world of Big Law. «New Suits» both reassures and gives a wake-up call to all of us in the business of providing legal services. Setting out both the opportunities and the threats engendered by the dynamic change in our industry, the book is an invaluable guide to all lawyers and legal business professionals wanting some insight on the challenges facing them in a globalized and accelerating world.»

– Dr Matthias Lichtblau, CMS«This book spells massive opportunity… for all those who get excited about change. Legal disruption isn’t coming, it has already been here for some time. Michele and Guenther provide an extremely well researched and thoughtful analysis of how that disruption is going to play out in the mid to long term. No scare-mongering here, but a really useful early-warning system for those wanting to profit from the innovation and efficiencies that market demand is successfully driving into every corner of the global legal sector.»

– Richard Macklin, Partner & Global Vice Chair, Dentons«This book comes at a time where we see just the beginning of a transformational change on the legal market. While such transformation is seen as a great opportunity for those participants who endorse change and innovations, others seem to be more frightened by potential disruption of their well-established business models. The structure and comprehensive contributor listing for this book encapsulates many disparate challenges faced by almost all players on the market. The lecture of the book should give good guidance to anyone who is interested in how the legal profession is (finally) modernizing, capitalizing on technology trends and becoming more client-centric.»

– Dr Cornelius Grossmann, Global Law Leader, EY Law«New Suits is signaling something different about the staid legal industry—evidence of a sincere appetite to change and potentially switch paradigms. Congrats to DeStefano and Dobrauz for pulling together an important and original work of applied research.»

– Professor Bill Henderson,Indiana University Maurer School of Law,Stephen F Burns Chair on the Legal Profession«‘Nomen est omen’ if you read the book title of ‘New Suits’. It encourages, allows and requests lawyers at all levels to rethink their former and existing ways of doing business in many areas of law. In the same, it outlines great opportunities to a new breed of experts in our profession. Thanks to the various authors, one gets a good understanding of how massive the impact of technology has become—and is going to be—to the legal services market. And the authors provide a distinct view of how a rather traditional profession will have to transform their business models to comply with the fast changes in the marketplace.»

– Jürg Birri, Global Head of Legal Services KPMG«New Suits provides an excellent overview of how, over the last few years, the legal ecosystem has become increasingly complex and the emergence of new business models has prevailed. From digitalisation to «moreforless» affecting both in-house legal teams and external law firms, New Suits exemplifies what it takes to become a «Modern Legal Services Business». It encapsulates the future of the legal profession through an ensemble of brilliant authors—an educating and thought-provoking read!»

– Alastair Morrison, Partner & Board Member, Pinsent Masons«The relevance of «New Suits» to considered thought on the state of the legal industry is profound. Other books predict a brave new world for the legal world, but glaringly offer no markers to when or at what scale such evolution will occur. DeStefano and Dobrauz bring clarity and energy to an area that has confounded most academic and business leaders. «New Suits» provides a single source of deep and broad understanding that is actually actionable—and is a must read for anyone who is or will be a leader in the field of law.»

– Daniel Reed, CEO, UnitedLexMichele DeStefano & Guenther Dobrauz

New Suits

Appetite for Disruption in the Legal World

Staempfli Verlag

Imprint/Legal notice

Imprint/Legal notice

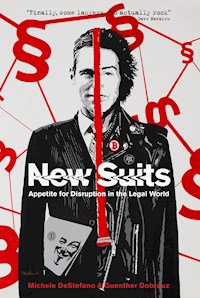

«Blurred Lines» cover artwork created for «New Suits» by Billy Morrison in Los Angeles in the summer of 2018 and used with kind permission.

Overall cover design by Tom Jermann of t42design/Los Angeles.

Photography (of cover art and portrait of Dr Guenther Dobrauz-Saldapenna)

created by Oliver Nanzig in Zurich 2018 and used with kind permission.

Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie;

detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar.

Alle Rechte vorbehalten, insbesondere das Recht der Vervielfältigung, der Verbreitung und der Übersetzung. Das Werk oder Teile davon dürfen ausser in den gesetzlich vorgesehenen Fällen ohne schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlags weder in irgendeiner Form reproduziert (z.B. fotokopiert) noch elektronisch gespeichert, verarbeitet, vervielfältigt oder verbreitet werden.

© Stämpfli Verlag AG Bern 2019

www.staempfliverlag.com

ISBN 978-3-7272-1035-8 (Print version)

ISBN 978-3-7272-1036-5 (E-Book pdf)

ISBN 978-3-7272-1043-3 (E-Book epub)

Content

Table of Contents

Professor Michele DeStefano and Dr Guenther Dobrauz-Saldapenna

Curators’ Foreword

Peter D Lederer

Prologue

Part 1: Why Do Lawyers Need New Suits?

01 Professor David B Wilkins and Professor María José Esteban Ferrer

Taking the «Alternative» out of Alternative Legal Service Providers

02 Professor Mari Sako

The Changing Role of General Counsel

03 Professor Michele DeStefano

Innovation

04 Professor John Flood

Legal Professionals of the Future

05 Christoph Küng

Legal Marketplaces and Platforms

06 Karl Koller

PropTech

07 Dr Marc O Morant

Gig Economy Lawyers and the Success of Contingent Workforce Models in Law

08 Dr Eva Maria Baumgartner

Virtual Lawyering—Lawyers In The Cloud

09 Michael Grupp and MichaManuel Bues

The Status Quo in Legal Automation

10 Karl J Paadam and Priit Martinson

e-Government & e-Justice: Digitizations of Registers, IDs and Justice Procedures

11 Dr Christian Öhner and Dr Silke Graf

Lawyer Bots

Part 2: What New Suits Might Lawyers Need for the Future?

12 Dr Guenther Dobrauz-Saldapenna and Corsin Derungs

Innovation, Disruption, or Evolution in the Legal World

13 Dr Matthias Trummer, Dr Ulf Klebeck and Dr Guenther Dobrauz-Saldapenna

Strategic Mapping of the Legal Value Chain

14 Simon Ahammer

Legal Publishers in Times of Digitization of the Legal Market

15 Professor Rolf H Weber

Smart Contracts and What the Blockchain Has Got to Do With It

16 David Fisher and Pierson Grider

The Blockchain in Action in the Legal World

17 Juan Crosby, Mike Rowden, Craig Mckeown and Sebastian Ahrens

eDiscovery

18 David Bundi

RegTech

19 Dr Marcel Lötscher

SupTech

20 Dr Antonios Koumbarakis

Legal Research in the Second Machine Age

21 Luis Ackermann

Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Legal Systems

22 Dr Christian Öhner and Dr Silke Graf

Automated Legal Documents

Part 3: How Will Lawyers Fit into The New Suits of the Future?

23 Maurus Schreyvogel

Fix What Ain’t Broken (Yet)

24 Jordan Urstadt

Law Firm Strategy for Legal Products

25 Dr Silvia Hodges Silverstein and Dr Lena Campagna

Legal Procurement

26 Tom Braegelmann

Restructuring Law and Technology

27 Philipp Rosenauer and Steve Hafner

From Legal Process and Project Management to Managed Legal Services (MLS)

28 Jameson Dempsey, Lauren Mack, & Phil Weiss

Legal Hackers

29 Noah Waisberg and Will Pangborn

New Jobs in an Old Profession

30 Salvatore Iacangelo

The Law Firm of the Future

31 Professor Michele DeStefano

The Secret Sauce to Teaching Collaboration and Leadership to Lawyers

32 Maria Leistner

The Importance of Diversity

Jordan Furlong

Epilogue

Eva A Kaili

Afterword

Appendix

Acknowledgements

List of Abbreviations

Curators and Authors

The appropriate response to new technology is not to angrily retreat into the corner hissing and gnashing your teeth: it’s to ask «Okay, how should we use this?»

– Burning Man** Caveat Magister, Technology and Immediacy at Burning Man(A slightly less than Socratic dialogue),Burning Man(Aug. 18, 2014), https://journal.burningman.org/2014/08/philosophical-center/tenprinciples/technology-and-immediacy-at-burning-man/ (last visited Apr. 30, 2019).

0

-Professor Michele DeStefano and Dr Guenther Dobrauz-Saldapenna-

Curators’ Foreword

Time to Leave Law-Law Land … and Head Back Into the Jungle

Technological advancements, globalization, and the recent financial crisis have fuelled unprecedented change in the legal industry. Against the backdrop of new business models, altered client expectations, and the fluidity of legal talent, the legal service delivery ecosystem of today and tomorrow is, in some ways, like that of a jungle i.e., difficult to navigate yet vibrant and flourishing. For that reason, we (the co-curators) designed this book to provide an international, multi-cultural map of the legal jungle. By putting together the voices of legal thought-leaders from around the world, this book is intended to display the changes unfolding across the legal marketplace today, varied outlooks on the future of the legal profession, as well as potential methods which law/legal professionals might employ for future success in a changed legal environment. To that end, the book is divided into three parts.

Part 1, Why Do Lawyers Need New Suits?, contains chapters that focus on the changing legal marketplace and its challenges; it provides various authors’ perspectives as to why lawyers need to don New Suits. For example, in chapter 1, Professors David B Wilkins and Maria José Esteban Ferrer demonstrate that what we call alternative legal services today is a misnomer and will be the norm in the legal market tomorrow. To meet clients’ changing expectations, lawyers need New Suits that are customizable and agile and which integrate law into broader business solutions. In chapter 2, Professor Mari Sako makes a parallel point about general counsels. In describing their evolving roles around the globe, Sako explains why general counsels will need to wear New Suits in an even more transient, international, and interwoven marketplace. Professor Michele DeStefano, Professor John Flood, and Karl Koller, in each of their respective chapters (chapter 3, 4, and 6), demonstrate why the wearers of these New Suits will need to hone new mindsets, skillsets, and behaviours to thrive.

In Part 2, What New Suits Might Lawyers Need for the Future?, the focus turns to predictions; herein, the authors attempt to foresee the impact, risks, and opportunities that technological advancements might have on the legal marketplace overall and, more specifically, on the jobs, roles, and careers of lawyers and law/legal professionals. For example, in chapter 12, Dr Guenther Dobrauz-Saldapenna and Corsin Derungs share their predictions of how the law marketplace will need to adapt and evolve to survive. In chapters 15, 16, 21, and 22, the authors focus more specifically on the technology they believe will help create the New Suits lawyers will wear in the future: e.g., blockchain, automated legal documents, and artificial intelligence. In other chapters, authors including David Bundi, Juan Crosby, Mike Rowden, Craig McKeown, and Sebastian Ahrens question and sketch the future needs and roles of legal teams and legal functions and what New Suits will be required as a result.

In Part 3, How Will Lawyers Fit into the New Suits of the Future?, the book turns to chapters that suggest methods and models professionals might leverage to not only meet but to exceed the needs and expectations of the critical stakeholders in the future legal marketplace (e.g., business clients, general counsels, and the public at large). In other words, this part is focused on how lawyers will fit into (or fill in) the New Suits identified by the other parts of the book. This part begins with a chapter by Maurus Schreyvogel (chapter 23). He utilizes the Novartis Journey to describe a model that can be employed by lawyer leaders to drive operational excellence in legal service delivery. Salvatore Icangelo outlines the law firm of the future (chapter 30), Professor Michele DeStefano, provides a methodology to teach leadership, collaboration, and innovation to law/legal professionals (chapter 31) while Maria Leistner, concludes our book fittingly by outlining how the new generations will wear New Suits to make more meaningful contributions to the world of law (chapter 32).

To remain authentic to the voices, cultures, views, and scholarly preferences of the authors, we did not edit these articles as traditional editors might; nor did we weave them together so that they read as one contiguous thread. Instead, each author’s chapter can be read on its own and represents his/her own research, citation style, and view point. We, the co-curators, analogize the compiling of this book to a quilting bee,1 a social gathering of legal thought leaders from around the world who have come together to tell stories about our time now (the dynamic state of the current legal marketplace) and to envision a viable future for the legal profession: a future in which we deliver not only more efficient but more effective and comprehensive services and solutions that help our clients and, at the same time, increase access to justice for all. This book, like a quilt, is designed to commemorate where we have been, where we are headed, and the why and how of both. This is because the future, unlike a jungle, is not formidable. The future is filled with fascinating and unfolding opportunities for the law/legal professionals who rise as leaders to hone and own their New Suits.

1 To understand the heritage of quilts and quilting bees seehttps://www.wonderopolis.org/wonder/how-do-quilts-tell-stories.

0

-Peter D Lederer-

Prologue

Thoughts on the Past and the Future of the Legal Profession

What was the practice of law like six decades ago? What is it likely to be in the future?

When Guenther Dobrauz asked me to ponder these questions for this book, he also asked if I would touch on my origins. This is also where, a bit earlier, John Flood had wanted to start the lengthy conversations that led to our work, Becoming a Cosmopolitan Lawyer. At first, I wondered why: The facts of my early life were of importance to me, of course, but why should they be to others? And what was their relevance to how I came to embark on a path that led to a career as a «global lawyer»? But of course, such requests caused me to reflect. And over time, what at first seemed to me a random walk through life revealed meaningful patterns and paths. I had largely followed what the Japanese anthropologist Uematsu once called «the aesthetic of drift», but it turns out that drift may be more purposeful than appears on the surface. Let me sketch what mine looked like.

Part I

The story begins in Frankfurt, where I was born of Austrian parents. My early childhood years were spent in 1930s Vienna, and then—separated from my mother—I was forced to emigrate. The destination was to the heartland of the United States, first to Indianapolis and after secondary school to Chicago. There I graduated from college at 19, dismayed to have learned (via undergraduate classes taught by the likes of Fermi, Szilard and Uhry) that I was not cut out to be a scientist of the quality I had aspired to be. Instead, I drifted into working for two years as a community organizer for the United World Federalists, as student director for New York and then as field director for Maine. Skills learned? Public speaking, group dynamics, recruiting volunteers, fund raising—and even lobbying.

Then followed conscription into the U.S. army, and two years of oppressively regimented life (fortunately without physical danger, since I was posted to Germany and not to the Korea of 1951). Here also, benefits flowed: learning to run a small team, how discipline in large groups worked, and how rigid hierarchies operated. In addition, I had the opportunity to relearn some German. Most importantly, it gave me the generosity of the GI Bill—the government stipends that helped pay the cost of attending law school for three years, plus two years of post-doctoral work.

I made the decision to attend law school while in the army. If I was not to work in the «hard» sciences, I would instead chose a discipline where (I thought) there was flexibility as to what one would do after graduation. I was accepted at Yale and the University of Chicago, and I chose the latter. One eye was still on the sciences: The part-time job I took to help pay for law school during the first year was in the University’s chemistry department, working for Professor Willard Libby, the Nobel Laureate who developed the carbon-14 dating method. It was no more than glorified bottle washing on a research project of his, but it was fascinating and there is something to be said for working with a genius on a daily basis!

Law school was a good fit for me: challenging, stimulating, and endless intellectual fun. The accident of starting in the summer quarter rather than in the autumn, gave me an elective after three quarters where my classmates had none. The one course that strongly appealed to me was Professor Karl Llewellyn’s Jurisprudence; it was only open to 3rd year students, but I asked for an exemption and he was kind enough to grant it. That, again, was an inflection point: at the end of the course, Llewellyn asked me to work for him as his research assistant. I did that for two years, and it is fair to say that the experience shaped my life, more than work on the Law Review or any other law school course. It was also, by the way, my first experience of research using data processing—in the form of an ancient IBM punch card sorter!

Exhibit 1: «IBM Card Sorter» [Source: National Institute of Standards and Technology Digital Collections, Gaithersburg (MD)].

The drift continued. Toward the end of my last law school year, the University of Chicago received a large grant from the Ford Foundation to establish a program in foreign legal studies. It sounded perfect for where my interests centered, but the program’s start was to be a year in the future. Once again, I took the risk of asking: might the law school be prepared to start early, and take me as the first student for a «trial run»? And Dean Edward Levi said yes! With that began an intense year. Five mornings a week, for two hours each day, I had tutoring in German law from Professor Max Rheinstein. He also arranged for a young Swiss law professor from Bern, Dr. Kurt Naef, who was spending a year at Chicago working on his Habilitationsschrift, to cover the same material with me each afternoon under Swiss law. To make life complete, I still had one regular law school course each quarter, plus the foreign law course, my work as the Law Review’s book review editor, and 20 hours a week working with Llewellyn. There were fringe benefits, of course. My German became more fluent, my vocabulary grew, and I learned sleep to be an unnecessary luxury!

The year in Switzerland that followed was marvelous, and under less pressure! Though I attended the lectures at the University of Bern, they were somewhat duplicative: the year of private tutoring with Rheinstein and Naef in German and Swiss law had taught me a good deal of what the lectures covered. But Professor Werner von Steiger, Rheinstein’s friend who had urged me to come to Bern, had also arranged for me to serve a clerkship at Bern’s Commercial Court. That proved a rich experience. The Court was composed of one professional and two lay judges, who heard a broad range of cases. One was a major trademark dispute between two cigarette companies that attracted Switzerland’s big-time trial lawyers. Another, my favorite, was an action for the purchase price of a quantity of cow intestines, bought by the defendant butcher for use as sausage casing and argued by him to be unfit for human consumption. The plaintiff, a gentleman who was both a lawyer and a cattle dealer, vigorously argued that the goods had been in perfect condition when delivered. He lost. I had a sense that the plaintiff’s having chosen to combine these professions influenced the Court very negatively!

I attended all hearings, learned a great deal from the lawyers’ arguments and the judges’ questions, and tried to predict how the court would decide. Would it be similar to how I thought a U.S. court would rule? Best of all, the court’s clerk, or Gerichtsschreiberin, Fräulein Fuerler, let me try writing first drafts of the Court’s judgment—and then with incredible kindness took the time to critique my drafts.

All too soon it was time to return to law school in Chicago; there I spent a year «cutting the academic umbilical», before beginning practice with Baker & McKenzie, briefly in Chicago and then in Zurich.

Exhibit 2: «Obergericht/Handelsgericht Bern» [Source: Wikimedia].

Part II

Revenons à nos moutons. What was it like to practice law sixty years ago? In many ways, indistinguishable from what it is today. Clients wanted to sell goods, or expand their operations, or acquire another company. They required help in puzzling through the tax or exchange control implications of a transaction. Occasionally, a dispute had arisen with a business partner that needed to be resolved, whether amicably or through formal dispute resolution. Sometimes they wanted to get married, or divorced, or adopt a child. Sometimes, albeit rarely in my practice, they found themselves in prison—or wished to avoid the risk of landing there.

Obviously, each and every one of these tasks is instantly recognizable to any newly minted lawyer today. But the changes brought about by six decades are profound. Think of the small things. You want to change a few sentences or re-order paragraphs in a draft agreement? That may mean re-typing all of it—word processing and computers didn’t exist. (Though a fortunate few had assistants who were artists at «cutting and pasting»; literally, with scissors and paste, though few today realize that this was the genesis of today’s keyboard commands.) If a lengthy document had to be re-typed, that often meant losing a day; only the largest of the New York firms had night-typing staff. London law offices went dark shortly after 5pm, and on the Continent the concept of night or weekend work was all but unknown.

Did a client want to talk? Well, trans-Atlantic telephone service existed, but not in a form recognizable today. There was no international direct dialing (New York became the first U.S. city to have that in 1970), calls had to be placed with an operator and often went through multiple operators at each end. Sound quality was poor, language skills could be a problem, and the cost? A three-minute call might cost as much as an hour of a lawyer’s time.

Exhibit 3: «Photograph of Women Working at a Bell System Telephone Switchboard» [Source: The U.S. National Archives/Wikimedia].

This is but a tiny sample of the hurdles and barriers one encountered and, as I said, these were the small things. Much more important were the barriers, seen and unseen, arising out of language, legal system, and culture. Consider: In the late 1950s, when I studied at the University of Bern, I was the first American to study law there in the history of the University. A decade later, when I came to practice in NYC, I thereby doubled the number of lawyers practicing there trained in both U.S. and Swiss law—there had only been one before my arrival. From the late 1940s, well into the 1960s, lawyers who were bilingual, and had trained in more than one legal system were a rare commodity. There were two obvious constraints: the cost of additional years of education, and the limited job openings for those brave few who nevertheless chose this path. Nevertheless, training in more than one legal system had incalculable virtues when counseling in international transactions. The civil law trained lawyer who could understand what a common law lawyer’s «needs» were when drafting a contract—and vice versa—brought a genuine benefit to the clients in greater efficiency and a sounder agreement. Similar benefits flowed from cultural sensitivity. A lawyer well sensitive to the other party’s background could, time and again, smooth negotiation roadblocks or prevent misunderstandings from threatening to wreck a transaction. The role of the lawyer could take on the qualities of a tour guide through strange legal country. Why were Anglo-American contracts so long, and continental European ones so short? Why did Japanese companies not use lawyers? What is a notary, and why is one so important in some countries?

In time, of course, these issues began to diminish in importance. Successive generations of lawyers and business people in steadily increasing numbers began to travel, and study, and work around the world. And by the early years of this century global lawyers and global networks were well established and no longer a novelty. Schools recruited young lawyers from around the world for their graduate law programs; top law firms in many countries began to place a premium on their hires having an LL.M. from abroad; and multi-national corporations hired legal staff from around the globe. At the same time, global business transactions had begun to increase exponentially in number, complexity and speed. Hand in hand with this came ever increasing layers of regulation and oversight: the modern world was upon us.

Part III

So much for the past; what of the present? While much of the world has changed, the legal world does so at what at best can be described as a very measured pace. One gets the sense that many lawyers and legal educators have looked up, blinked, and seen that we have entered the 21st Century. They do not seem to be aware that almost a fifth of it lies behind us. Like most of humanity, they have picked up the shiny things of our age: the cell phones and tablets and other gadgets, the gig-economy services, the Cloud, the apps, the Internet of Things… and, of course, the new vocabulary that comes with this. Look just below the surface, however, and for a large number of those who practice or teach the law very little has changed. Contracts still get written as if each were a case of first impression. Students sit at their classroom desks and often hear lectures so little changed from year to year that course notes are found for sale online.

It is different for the consumers of legal services, at least for that segment of the market that can afford to pay. This is the segment that is increasingly discontent with what is on offer, and has the muscle to enforce change. And change is, indeed, coming apace! For much of history, in much of the world, one went to law firms for legal advice; today, there are alternatives. Let me note three: the expansion of corporate law departments, the growth of law companies, and technological solutions.

The increase in power wielded by «in house» counsel, and the growth in their number, has been steady. One important factor has been management’s need for counsel that fully «understands our business» in a way that outside counsel rarely does. Coupled with that is often the need to have inside lawyers work as an integral part of project teams—a role often totally unfamiliar to outside lawyers, but a role that is increasingly demanded by the needs of modern global business. Finally, there is the inexorable pressure to reduce costs, a pressure that is hardly novel, but is made particularly painful by the opaque system used by most lawyers to charge for their services: the billable hour. It is perhaps ironic that corporate counsel, decades ago, fostered this method of charging to obtain greater clarity, a substitute for the terse «For professional services rendered from __ to__». In the event, it has led to an ever-increasing desire to use internal legal resources with much more predictable, and often lower, costs. The big law firms have hardly disappeared, but their number has shrunk and they are under unrelenting pressure.

Law companies, sometimes called alternative legal service providers, are another rapidly growing source of legal help. The Big Four global accounting firms, some twenty years after Arthur Andersen’s Enron debacle largely put expansion into the legal sphere on hold, are once again on the march. Their scale, capital resources, global reach, and business sophistication make them formidable entrants into the field. All four of these firms have now availed themselves of the UK’s Legal Services Act to establish Alternative Business Structures, allowing them to hold professional, management and ownership roles in UK law firms. Penetration into the US market is significantly more difficult to achieve, but it would be shortsighted to say it is impossible. Are the Big Four thus destined to take over the legal world? It is probably too early to tell. The very dominance of their market position, combined with the unresolved tensions of providing both audit and non-audit services, may well prove limiting factors. It is also possible, however, that other pressures may force some separation of these two service branches. If so, the non-audit part might emerge as an even stronger competitor.

But the world of law companies does not stop with the Big Four. The last few years have seen spectacular proliferation and growth of companies that have rethought how—and importantly by whom—legal services can be delivered. They may not yet be household names, but firms such as Axiom, Consilio, Elevate, LegalZoom, PartnerVine, Riverview Law, Thomson Reuters and UnitedLex are but a small sample of firms that play a significant role in this market. Whether by offering alternative career paths, or utilizing labor arbitrage, or breaking down tasks into legal and non-legal components, or mixing technology with human labor, or re-thinking the workings of law departments, these firms have been successful in «deconstructing» the approach of the conventional law firm. They have been able to rid themselves of many of the burdens that conventional law firms suffer from: archaic management and ownership structures, cost burdens, inflexibility, and—to be blunt—arrogance!

Exhibit 4: «Avocat au parlement de Paris» [Source: Wikimedia].

And then of course there are the changes being brought by technology. As always with new developments, it may be difficult to distinguish solid achievement from hyperbole, or the fully functional from fashionable trappings. The global proliferation of new «crypto» centers, dubious ICOs, roller-coaster behavior of crypto currencies, an endless stream of conferences on AI or Blockchain or big data…all these tend to spur skepticism in many. But make no mistake: the changes in how legal services can be delivered are real, are accelerating, and are profound. When the bulk of the post-millennial generation enters the legal workforce, much of how law is practiced today will seem as quaint as a busy signal, or a fax machine, or a paper pad and a pencil.

The pressure felt by conventional law firms from the emerging competitors and the advent of technological efficiencies is increasing. Some firms seek to gain strength by bulking up via mergers and acquisitions. Others seek to «flatten» their conventional pyramid structures, reducing their hiring of new graduates and increasing their hiring of more seasoned professionals. Some have looked to build global centers for non-lawyer (or lower cost lawyer) support services. Still others have sought to integrate new technologies into their current workflow so as to work more efficiently and effectively. A brave few have even sought to bring legal operations skills into their practice to truly focus on meeting their clients’ needs—how successfully they have done so is still too early to judge.

This all, of course, is in its early stages. The investment of a few millions in a new legal enterprise is still enough to make headlines around the world. The behemoths of Big Law continue to dominate much of the legal world. But the horizon is no longer cloudless, and on a very quiet night one can hear creaking noises as these majestic vessels sail.

What then of legal education? For decades, legal education has been a growth business; throughout the world, the number of law schools has increased with ever-larger numbers of students enrolled. Tuition, in much of the world, has been on a similarly dizzying upward spiral. To take a single example, in just twenty-five years tuition at one well-regarded law school, The University of Michigan, has tripled. The arguments for why this should be so are many, and often passionate, but on balance unconvincing. This is particularly so in view of the fact that since the financial crisis of a decade ago, enrollment has been declining. Moreover, as is often the case when the practice world feels threatened by the onslaught of something new, here the new entrants and technology, there is a chorus of complaint that the law schools have failed to ready their graduates for the «new world». (There may be a kernel of truth in the complaint; schools rarely lead the professions in anticipating future needs.)

In any event, declining enrollment has caused belt-tightening at a number of schools around the world, as tuition costs skyrocket and job opportunities—in conventional high-paying jobs—shrink. Very slowly, at least to the eye of the outside observer, some schools are beginning to think hard about what the law job of the future might look like. Will every person who works in providing legal services require the identical, costly, training? Are the traditional skills of a lawyer all still required? Does the «one size fits all» approach in training still make sense? How are the new skills to be learned that legal work increasingly requires? To what degree do licensing requirements make sense: are they essential protection of the public or largely anticompetitive entry barriers? The questions are almost endless, the appetite to tackle them is limited, and it is not easy to see a timely and good resolution within reach. The risk of aimless drift is real.

Exhibit 5: «Driftling» [Source: Wikimedia].

To say that change is extremely difficult is not, however, to say that it is impossible. In all corners of the world a growing number of legal educators have seen and acted on the need to enhance and modify existing curricula to better serve the needs of our time. Where in the middle of the last century law schools began to recognize the need for young lawyers to be financially literate, today the need is seen for training in new skills: an understanding of technology, statistics, and data analytics, to name a few. With this has come the rising recognition of the need for the ability to work on teams, often with those of other disciplines, cultures, languages and legal systems. These efforts are embryonic, but a program such as Michele DeStefano’s LawWithoutWalls, at the University of Miami School of Law, has been in existence nearly a decade. Through its alumni’s proselytizing, and demonstrated results, it has helped launch new educational approaches around the globe.

Further pressure for change comes from the client side. Not through the ancient complaint that graduates are not «practice ready»—they never have been—but by way of ever-stronger nudges that what is wanted are young lawyers who have an understanding of the tools of the modern legal and business world. A «hint» from a giant corporation that it prefers to recruit graduates from schools that supply such training can work wonders. Let me also add the obvious: educators, bar associations, and regulators include a great many wise people in their number. They see the problems and use their very best efforts to bring about badly needed change. But educational institutions and bar bodies are slow moving; efforts to change them are to be applauded and supported, but whether they can timely change is an open question.

Part IV

I have spoken of the providers of legal services, and of those whose task it is to educate those providers. Before I turn to the future, something needs to be said about the consumers of legal services: those who require aid in arranging their legal affairs or in seeking justice. Here there is a harsh dilemma: earlier I mentioned «that segment of the market that can afford to pay». This world of large enterprises and institutions, and affluent individuals, can pay the cost of legal services, even if it does so grudgingly and even as it seeks, often successfully, to reduce such costs. Not so, unfortunately, for most of the world which, simply put, cannot afford access to justice. How large is the number so denied access? It varies from place to place, but it is often thought that 80 percent or more of those requiring legal help may be unable to obtain it. That figure, or anything like it, is a calamity. A just world cannot afford to shut out the vast majority of its peoples from the instrumentalities of justice. Thus, when I consider the future of law, I do so on the premise that correcting this imbalance must be a prime goal. That will not be an easy haul. In a world where the elimination of hunger, the eradication of lethal diseases, or providing adequate shelter for all, are still distant goals, access to justice may strike some as being of lower priority. It is not; it is an essential need of humanity. But how is it to be met?

It is here the technological revolution that we see before us may hold great hope, though at the moment this is more Zukunftsmusik than practical reality. The number of «consumer-facing» software programs and apps is growing, but still small. It is clear, however, that the explosion of digital data available, coupled with advances in data analytics, machine learning, and the decreasing cost of computer power, opens the door to the realization of genuine change. Equally important, there is enhanced pressure from governments, academics, bar groups, and many others to push change. Some of this, obviously, encounters deeply entrenched resistance: few trade guilds welcome the loss of monopoly power with open arms and lawyers are hardly an exception. It is also important to realize that access for all, in law as in medicine, comes at a price. The chatbot may lack the comfort of human warmth; technology has its own values and these may differ from those of law. Nevertheless, there is significant hope to be found in online dispute resolution, law bots and apps that provide easy and free, or modest-cost, solutions to common legal issues, and much more.

What else might technology hold for the future of law? When I look at the marvels—and, alas, the horrors—of the world around us, I am often amazed by how frequently writers of science fiction whom I admired 70 or even 80 years ago were able to predict today’s world. Today’s crystal balls seem more clouded. There is a burgeoning body of literature that argues, with varying degrees of plausibility, that the singularity—and with it the robot lawyer—is just around the corner. New cottage industries have sprung up to exploit the possibilities to be found in the new universe of distributed ledger technology. Indeed, cities and even small countries vie to be seen as the centers for this new wisdom. Fortunes have been made—and lost—in the space of days or even hours. No week passes without a series of hackathons, meetups, and conferences devoted to exploring the brave new world of technology. Is there a problem seeking a solution? There is an app for that!

This is not said to belittle or scoff at these developments. They carry with them the excitement of new approaches that could truly change «the world as we know it». Nor should the flashier parts of what we see distract us from the fact that significant, sound, and powerful technological advances have been made in the world of law. Some have been broadly adopted, others are being tried, still others await the slow process most innovation goes through before becoming commonplace. But technology is on the march and, as with all genies, unstoppable once out of the bottle.

And so I come to the final question: what is this future that lies before us? As an old Danish proverb notes, it is difficult to make predictions—especially about the future. Moreover, as a colleague recently noted, perhaps it is simply too early in the game to make good calls on what it all means. Still, I will risk one prediction: The world today, tomorrow, and as far out as imagination can reasonably carry us has and will have a need for «lawyers»: as stewards of justice, in the sense of defenders of the rule of law and officers of the court, and as advocates and trusted advisors. Lawyers will not disappear. As a long-forgotten futurist once noted, we will continue to be the warm, wonderful, caring people we have always been, but there will be fewer of us, and more of our remuneration will be psychic rather than monetary. Why? Because much of what now is lawyer’s work will indeed be taken over by machines and their algorithms, and workers whose training and thus cost is significantly less than that of a conventional lawyer. That, however, as you will read in my colleagues’ essays that follow, is not cause for despair.

While the world we live in is one of extraordinary complexity and lightning fast technological change, the legal world has responded! Whether it is exploring the impact of AI, or analyzing the new structures of law practice, the changing roles of law departments, Blockchain and its progeny, the training of lawyers for the new age…all this and more is thoughtfully explored below. You will find, as you read, that this is a world in flux: there are no long-standing precedents for resolving disputes around an ICO, no years of experience to draw upon in resolving the ethical dilemmas of an artificial intelligence experiment gone awry. No, the urgent need that has evolved is the ability to extract from the past and extrapolate to the future, with sharp awareness that many of the sharpest questions are not just legal. Instead, we often find a need to pull together all the wisdom our collective possesses: from science, ethics, and business sense to behavioral psychology, philosophy, and beyond. A popular view today is that we need more T-shaped lawyers, where, in Wikipedia’s description

«The vertical bar on the T represents the depth of related skills and expertise in a single field, whereas the horizontal bar is the ability to collaborate across disciplines with experts in other areas and to apply knowledge in areas of expertise other than one's own.»1

And that, perhaps, is where I come around full circle to my own shaping. By accident, fortune both bad and good, and drift, I came to be a T-shaped lawyer—though in my day we probably had this in mind when we said «well-rounded». Should others repeat my path? Most obviously not. But there is much to be said for fostering and encouraging schooling, training, and experience that seek to create multi-skilled generalists. We then will have the beginnings of a workforce best equipped to deal with the world before us—a world, it might be added, that needs all the help it can get! Lawyers are well-known for «making haste slowly»; perhaps for once we can do it differently—and when we put on the «New Suits» of our title, we will be able to move with the speed our time requires.

«Thus, though we cannot make our sunStand still, yet we will make him run.»

– Andrew Marvell, To His Coy Mistress (1681)Sources of Images and Photographs

IBM Card Sorter

Source: https://goo.gl/t88hHr

Obergericht (Handelsgericht) Bern

Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/14/Obergericht_des_Kantons_Bern.jpg

Bell Telephone Operators

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Photograph_of_Women_Working_at_a_Bell_System_Telephone_Switchboard_(3660047829).jpg

Avocat

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:20101019-031-Mus%C3%A9e_du_Barreau_de_Paris.jpg

Drifting

Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/04/Japanese_house_adrift_in_the_Pacific.jpg

1 Wikipedia, T-shaped skills(January 14, 2019, 1:15 PM), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T-shaped _skills.

Part 1:

Why Do Lawyers Need New Suits ?

00000000

01

-Professor David B Wilkins and Professor María José Esteban Ferrer1-

Taking the «Alternative» out of Alternative Legal Service Providers

Remapping the Corporate Legal Ecosystem in the Age of Integrated Solutions

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. From Oligopoly to Global Supply Chains: The Evolution of the Corporate Legal Services Market

A. ALSP 1.0: The Cravath System

B. ALSP 2.0: The In-House Counsel Movement and Its Progeny

1. ASLP 2.1: Outsourcing and Offshoring

2. ALSP 2.2: Temporary staffing

3. ALSP 2.3: MDPs

C. The Empire Strikes Back

III. ALSP 3.0: The GFC and the Integration of Law into Global Business Solutions

A. From Outsourcing and Offshoring to Nearshoring and Partnerships

B. From Temporary Staffing to Agile Work

C. From MDPs to Integrated Solutions

IV. Conclusion

V. Bibliography

A. Hard Copy Sources

B. Online Sources

C. Other Sources

1 David B Wilkins is the Lester Kissel Professor of Law, Vice Dean for Global Initiatives on the Legal Profession, and Faculty Director of the Center on the Legal Profession, Harvard Law School. María José Esteban is a Ramon Llull Contracted Doctoral Professor and a Lecturer of Business Law in the Department of Law at ESADE, and Senior Research Fellow and Co-Director (along with Professor Wilkins) of the Big 4 Project at the Harvard Law School Center on the Legal Profession.

The word «alternative» is definitely trending in the legal zeitgeist. Beginning with the U.K. Legal Services Act and accelerating through the legal tech startup boom, discussion about the growing importance of Alternative Business Structures (ABS) and Alternative Legal Service Providers (ALSP) has become a cottage industry in the legal press, and increasingly in the legal academy as well. And for good reason. According to a recent report by Thomson Reuters, Georgetown Law Center on Ethics and the Legal Profession, the University of Oxford Said Business School, and Acritas (a leading provider of legal market intelligence)—a collaboration that in and of itself is a powerful indication of how widespread the discussion of this topic has become—revenues from ALSPs grew from USD 8.4 billion in 2015 to USD 10.7 billion in 2017—a compound growth rate of 12,9% (Thomson Reuters et al. 2019). Nor is this growth limited to just a few industries or kinds of alternative services. As the Thomson Reuters report documents, more than one-third of companies, and over fifty percent of law firms, report that they are currently using at least one of the top five functions typically performed by ALSPs. At the same time, all four of the Big 4 accountancy networks – PwC, Deloitte, EY, and KPMG—have received Alternative Business Structure licenses to operate as multidisciplinary practices (MDPs) in the U.K. (Evans 2018a). Given the exponential growth in the number of legal startups over the last few years (Law Geek 2018), it is no surprise that practitioners and pundits alike expect that «competition from non-traditional services providers will be a permanent trend going forward in the legal services market» (Altman & Weil 2018, at 1).

And yet, for all of the talk about the growing importance of these «alternatives», the very discourse used to cast these new providers as the harbingers of impending dramatic changes in the market for legal services continues to marginalize and mask their true significance. Specifically, by labeling everything from legal tech startups, to long-established outsourcing and electronic discovery providers, to leading information and technology companies and the Big 4 as «alternatives», the current debate reinforces the prevailing wisdom, as succinctly stated by John Croft, President and Co-Founder of Elevate, that «there is one ‹proper› way of providing legal services (i.e., going to a traditional law firm) and any other way is ‹alternative› (i.e., wrong/new/risky!)» (Artificial Lawyer 2018).

It is not surprising that the discourse has evolved in this fashion. In medicine, for example, «authorities have devoted significant energy and resources to making sure that alternatives maintain lesser status, power and social recognition either alongside or within the margins of dominant systems» (Ross 2012, at 6). Given that lawyers exert even more control over the regulatory system that governs law than doctors do in medicine, it is entirely predictable that incumbents have worked hard to cabin the legitimacy of these potentially «subversive» elements of the legal ecosystem, to borrow Ross’s evocative phrase about medicine, as «alternatives» to «real» law firms. Indeed, even the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines alternative as «different from the usual or conventional; existing or functioning outside the established cultural, social, or economic system». As a result, the only unifying definition that Thomson Reuters et al. (2017, at 1) could muster in their original report on this phenomenon was to say that ALSPs «present an alternative to the traditional idea of hiring a lawyer at a law firm to assist in every aspect of a legal matter». Tellingly, their 2019 report makes no attempt at all to define what constitutes an ALSP (Thomson Reuters et al. 2019).

In this Chapter, we argue that this characterization of the range of new providers competing for a share of the global corporate legal services market is fundamentally flawed. This is not because we believe that we are about to witness «The Death of Big Law» (Ribstein 2010), or even more dramatically, «The End of Lawyers?» (Susskind 2008). To be sure, some law firms will surely «die», and some lawyers will surely lose their jobs. Nevertheless, we believe that so-called «traditional» large law firms will continue to occupy an important place in the legal ecosystem for the foreseeable future—although as we suggest below, the law firms that prosper will be those that harness what we will define as «adaptive innovation» to respond to the changing needs of their clients (Dolin & Buley 2019). But the ecosystem in which both law firms and a wide range of other providers will compete is one that will increasingly require the integration of law into broader «business solutions» that allow sophisticated corporate clients to develop customized, agile, and empirically verifiable ways of solving complex problems efficiently and effectively. As this ecosystem matures, it will both decenter traditional understandings of how to provide high quality legal services, while at the same time raising critical questions about how to preserve traditional ideals of predictability, fairness, and transparency at the heart of what we mean by the rule of law. Understanding the dynamics of this new ecosystem will be critical for all legal service providers seeking to do business in the new global age of more for less.

Our argument proceeds in three parts. In Part II we briefly locate the current demand for ALSPs within the broader context of the large-scale forces that are reshaping the global economy, and therefore inevitably reshaping the market for corporate legal services in which both «traditional» and «alternative» providers compete. These forces, we argue, are producing a market that favors «integrated solutions» and value-based pricing over traditional domain expertise purchased on a fee for service basis. In Part III, we discuss the implications of this trend for legal service providers of all types. Specifically, we argue that corporate clients will increasingly demand professional services that are «integrated», «customized», and «agile». These demands, in turn, will move what are now considered «alternative» providers such as technology companies, flexible staffing models, and multidisciplinary service firms like the Big 4 to the core of the market, while putting pressure on law firms to articulate how the services that they provide contribute to producing integrated solutions for clients. Finally, in Part IV we conclude by identifying some key challenges that this new corporate legal ecosystem poses for legal education, legal regulation, and the rule of law.

II. From Oligopoly to Global Supply Chains: The Evolution of the Corporate Legal Services MarketThe first thing that is misleading about the current discourse that seeks to define a set of «alternatives» to traditional law firms is that it frequently equates «alternative» with «new». Thomson Reuters et al. (2017, at 1) original report on ALSPs is typical. After asserting that «[t]raditionally, clients looked to law firms to provide a full range of legal and legally related services», the report states that «[t]oday, by contrast, consumers of legal services find themselves the beneficiaries of a new and growing number of nontraditional service providers that are changing the way legal work is getting done» (Id.). But this way of characterizing the current suite of «alternative providers» fails to acknowledge that clients have been looking for alternative ways to source legal services for more than a century—starting with engaging what we now consider to be «traditional» law firms. This historical context is critical to understanding the contemporary market for corporate legal services and its likely future.

A. ALSP 1.0: The Cravath SystemIronically, what we now consider to be the «traditional» mode of providing corporate legal services was once itself an «alternative». Prior to the turn of the twentieth century, there were no large law firms in the United States, or for that matter, anywhere in the world. The overwhelming majority of lawyers were solo practitioners, or worked in small and loosely affiliated law firms, serving a mix of individual and business clients primarily by appearing in court. To the extent that America’s businesses had legal needs, they were serviced either by internal lawyers—for example, David Dudley Field, Chief Counsel to the Erie and Lackawanna Railroad, who was one of the most powerful (and arguably corrupt) lawyers in the latter decades of the nineteenth century—or by a mix of solo practitioners and self-help. It was not until the early decades of the twentieth century that lawyers like Paul Cravath, Thomas G. Sherman, and John W. Davis created what has come to be known as the «Cravath System»—formally organized law firms consisting of «associates» and «partners» hired directly from top law schools, providing a full suite of services to big corporations—that we now take for granted as the norm against which all other service providers should be judged (Galanter & Palay 1991). Moreover, like all «alternatives», the Cravath System was considered subversive by the legal elites of the day. Committed to the traditional ideal of lawyers as «independent professionals» modeled on the self-employed English barrister, as late as the 1930s these elites derisively described Cravath and other firms as «law factories» that were destroying the soul of the legal profession (Galanter & Palay 1991). Yet by the 1960s, large law firms following the Cravath System were universally viewed as the gold standard for providing legal services, attracting top talent, and sitting atop the income and prestige hierarchy of the profession (Smigel 1964).