7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

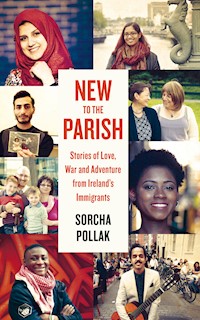

An inspiring chronological timeline of personal stories of migration, New to the Parish: Stories of Love, War and Adventure from Ireland's Immigrants takes us on a journey across the globe – from Cameroon to Myanmar, Poland to New York, Nigeria to Venezuela, Iraq to Syria – and back home again. These fourteen stories are given context by succinct analysis of how world events over the past decade have played a role in the migration crisis; from the 2004 enlargement of the European Union to the economic recession, the outbreak of the Syrian conflict in 2011 to Angela Merkel's welcome of over a million people into Germany, and from Brexit to the election of Donald Trump as US president. Irish Times journalist Sorcha Pollak, whose own grandfather was a Czech Jewish political refugee who arrived in Ireland in 1948, provides a deeper understanding of what makes a person leave their native land, often in extreme difficulty, in order to start a new life abroad. These are the stories of people who have come to Ireland for work, education, retirement, love and in some cases, out of necessity, forced from their homes by death and destruction. New to the Parish is an important reminder that every migrant is a human being, and that every one of us has a story to tell.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

New to the Parish

Stories of Love, War and Adventure from Ireland’s Immigrants

Sorcha Pollak

NEW TO THE PARISH

First published in 2018 by

New Island Books

16 Priory Hall Office Park

Stillorgan

County Dublin

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Sorcha Pollak, 2018

The Author asserts her moral rights in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-678-0

Epub ISBN: 978-1-84840-679-7

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-84840-680-3

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

Contents

Glossary of Terms

Introduction

2004 Migration

Bassam Al-Sabah, 2004

2005 Migration

Magda Chmura, 2005

2006 Migration

George Labbad, 2006

2007 Migration

Azeez Yusuff, 2007

2008 Migration

Tibor and Aniko Szabo, 2008

2009 Migration

Mohammed Rafique, 2009

2010 Migration

Zeenie Summers, 2010

2011 Migration

Carlinhos Cruz, 2011

2012 Migration

Chandrika Narayanan-Mohan, 2012

2013 Migration

Mabel Chah, 2013

2014 Migration

Flavia Camejo, 2014

2015 Migration

Ellen Baker and James Sweeney, 2015

2016 Migration

Maisa Al-Hariri, 2016

2017 Migration

Eve and Maybelle Wallis, 2017

Endnotes

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

For my parents, Andy and Doireann.

Glossary of Terms

Migrant: A migrant is someone who moves from one place to another in order to live in another country. According to the International Organisation for Migration, over one billion people in the world are migrants, or more than one in seven people globally.

Asylum seeker: An asylum seeker is a person who has left their country of origin because of a fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion. An asylum seeker formally applies to the host state for a declaration as a refugee, and is legally entitled to remain in that state until their application is decided. They must demonstrate their fear of persecution is well founded and must remain an asylum seeker until their application for refugee status is processed (the Irish government believes that some asylum seekers are in fact economic migrants). An asylum seeker becomes a refugee if their application for protection as a refugee is successful. In 2016 there were 2.8 million asylum seekers globally.

Refugee: A refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war or violence. A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership of a particular social group. Most likely, they cannot return home or are afraid to do so. Refugees are protected under the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, which Ireland has signed and ratified. More than half the world’s refugees come from just three countries: Syria, Afghanistan and South Sudan. Another 5.2 million refugees come from Palestine.

Programme refugees: A programme refugee is a person who is given leave to enter and remain in the State for temporary protection or who has been resettled as part of a group in response to a humanitarian crisis and at the request of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Since 2000, more than 1,800 refugees from almost thirty countries, including Iraq and Syria, have been admitted as programme refugees for resettlement in Ireland.

Irish Refugee Protection Programme: The Irish Refugee Protection Programme was established in September 2015 as a response to the migration crisis in southern Europe. Under the programme, the Irish government pledged to accept up to 4000 people into the State within two years—2,622 people through EU relocation from Italy and Greece and 1,040 programme refugees through resettlement from camps in Lebanon and Jordan. By December 2017, 1,502 people had arrived in Ireland.

Internally displaced person: These are people who are forced to flee their homes but do not cross international borders. Some 40.3 million people worldwide are internally displaced, according to the UNHCR.

Economic migrant: An economic migrant is a person who has left his or her country to find employment in another country. Citizens of all EU countries have the right to come to Ireland to seek employment.

EEA national: A national of the European Economic Area, which is made up of all EU member states along with Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. The latter three countries are members of the EU’s single market but not of the European Union itself. Switzerland is neither an EU nor an EEA member but is part of the single market, meaning Swiss people have the same rights to live and work in other European countries as other EEA nationals.

Non-Irish national: A person who is not a citizen of Ireland.

Direct provision: The Irish system for accommodating asylum seekers. Established in 2000, the system was set up to provide shelter to asylum seekers for six months whilst their application for refugee status is being processed. The vast majority of asylum seekers spend much longer than six months in the system and in 2016 the average length of stay was nearly three years. They are accommodated in privately run centres which provide food and board for residents. Asylum seekers in Ireland are not allowed to work (although this may change for some of them following a May 2017 ruling of the Supreme Court) and are not entitled to the usual social welfare payments. As of June 2017, asylum seeking adults receive a weekly cash allowance of €21.60. The allowance for children was also raised to €21.60 per week.

Introduction

Stephen Pollak knew very little about Ireland the day he stepped off a plane in Belfast airport seventy years ago. Like the small number who had come before him and the many hundreds of thousands that would follow, he had arrived on this small island on the fringes of Western Europe to begin a new life. After more than a decade of war, journalism, clandestine work and imprisonment, life in rural Ireland would have felt very foreign to this Czech immigrant. The hospitality he received from a Northern Irish family that was totally disconnected from his previously dangerous and fractured life—as a left-wing Jew in wartime Europe—serves as a reminder of how important a warm welcome can be.

Stephen Pollak was my grandfather. He arrived at my maternal great-grandparents house in Kellswater, outside Ballymena in County Antrim in April 1948 as a political refugee who had come to Ireland to join my grandmother, Eileen Gaston, after a whirlwind affair and subsequent marriage in Prague. She was pregnant with my father who was born a month later. Eileen had moved to Prague after the Second World War to teach English and there, in February 1947, at a party after an ice hockey match between Czechoslovakia and the USA, she met a young journalist named Stephen.

Born in Berlin in 1913 to prosperous Jewish parents from Bohemia, Stephen renounced his privileged upbringing of boarding schools and skiing holidays and left art school in London to join the International Brigades and fight in the Spanish Civil War. He was badly wounded—walking with a heavy limp for the rest of his life—in the battle for Madrid in 1937 and became a Communist sympathiser in the years that followed. After he recovered from his injuries he worked as an undercover courier for the Communist Party, travelling around Central and Eastern Europe with a fake Canadian identity. In 1941 he was arrested by the British authorities in India for being a Communist spy and was imprisoned for the duration of World War II in the city of Dehra Dun in the foothills of the Himalayas.

He returned to Europe in 1946 and found work as a journalist with a left-wing English language magazine in Prague. However, after the Communists seized power in February 1948, and despite his Communist sympathies, my grandfather was accused of writing in support of US policies, lost his job and was visited by the secret police. He acted quickly and booked my heavily pregnant grandmother onto a flight back to Britain. Shortly afterwards he fled the country on foot, walking over the border into Austria under cover of darkness before flying to London en route to Northern Ireland. While my grandparents only remained in County Antrim for a short while after my father was born—they eventually moved to London—my grandmother’s Presbyterian family welcomed this strange, limping young foreigner with great kindness. They and their neighbours in that small rural community were able to see through the brash exterior of this adventurous young man to the humanity which lay beneath—to a lonely exile who had lost family and friends during a decade of war and displacement, but who had finally found love and acceptance in the arms of a young Irish woman.

In recent years people have often asked why I express such interest in the lives of refugees. What is it about their plight and suffering that inspires me to tell their stories? Like nearly every Irish person, I am descended on my mother’s side from emigrants (from Cork) who left for the United States. However, I am also the descendent of an immigrant—a person with nowhere else to go who came to this country as a refugee. I have grown up with the awareness that had my mother’s Northern Irish family not welcomed my grandfather, the future of my own family could have turned out very differently.

Growing up in Ireland in the 1980s and 1990s my Polish surname was considered exotic. Ireland was a culturally homogenous island with very little understanding or experience of immigration. And why would we? Several centuries of hunger, poverty and unemployment hardly made this small island an attractive destination. However, there were some, like my grandfather, who did arrive on Irish shores in the late nineteenth and early-mid twentieth century. They were not always made welcome: we pride ourselves on being the home of one hundred thousand welcomes, yet ours has not always been a very noble history when it comes to those in need.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century a small number of Jewish people arrived in Ireland, many of them seeking asylum from increasing anti-Semitism in Russia. There were an estimated 4,800 Jews in Ireland by 1904, most of them in Dublin but some also in Cork and Limerick. Their welcome in that latter city was short-lived and in early 1904, 35 families living there were attacked and forced to leave in what became known as the Limerick ‘pogrom’. The Irish response to German and Austrian Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s, was unwelcoming, with the government implementing an extremely restrictive refugee policy. In the mid 1940s the Department of Justice initially refused to allow 100 Jewish orphaned children, survivors of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, a temporary refuge in Ireland, calling Jews ‘a potential irritant in the body politic.’ Taoiseach Éamon De Valera eventually allowed the children into Ireland on a temporary basis.

In 1956 Ireland welcomed 540 refugees from Hungary following the Soviet invasion. However the new arrivals quickly became disillusioned with being housed in army barracks in County Clare and went on hunger strike to draw attention to their ‘sit and rust’ existence. The immigrants—many of whom had worked as miners, technicians and craftsmen in Hungary—argued that while Ireland had accepted them as refugees, the State did not care about their future. The vast majority of them eventually left Ireland and moved to the United States and Canada.

In 1973 voluntary and charity groups lobbied for the Irish government to offer refuge to Chilean refugees fleeing from General Pinochet’s right-wing military coup. However the Department of Justice argued that Irish society was ‘less cosmopolitan than that of Western European countries generally and in consequence, the absorption of even a limited number of foreigners would prove extremely difficult’. It also expressed fear at the political ideologies of these Chilean arrivals, saying that most of them had become refugees because ‘they are Marxist and probably communists’. The government eventually agreed to admit around 120 Chilean refugees. In the years that followed groups of Vietnamese, Iranian, Bosnian, Kosovar, Kurdish, Sudanese, Congolese and Burmese (Rohingya and Karen ethnic minorities) asylum seekers, as well as people from other countries, would also be resettled in Ireland.

While Ireland did become one of the first six countries in Europe to establish a UN-sponsored resettlement programme in 1998 for refugees fleeing war and persecution, our nation’s claim of being able to empathise with migrant suffering given our own turbulent past does not always ring true. Our current record of providing refuge to asylum seekers fleeing conflict and poverty in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia remains underwhelming. In October 2017 there were 4,838 women, men and children living in direct provision—a system established in 2000 as a temporary housing solution for asylum seekers. In 2016 residents were spending an average of nearly three years waiting for a decision on their status (i.e. whether and on what basis they are going to be allowed to stay in Ireland). While the question of asylum seekers’ right to work was finally addressed in May 2017, when the Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to prevent people in direct provision from seeking work, many question marks remain over the length of time people spend in these centres and the conditions they live in. Meanwhile the Irish Government’s target of welcoming 4,000 asylum seekers from camps in Greece, Italy, Lebanon and Jordan is minute when compared to the hundreds of thousands of people accepted by countries like Germany and Sweden since 2015.

Nearly three years ago I began writing a series for The Irish Times about people who had come to live in Ireland. While New to the Parish did coincide with a barrage of reports about asylum seekers moving en masse towards Europe, the series did not happen because of the migrant crisis. The idea stemmed from the increasing diversity in Irish society that has developed over the past ten to twenty years. The hope was to offer an insight into the motivations of the immigrant, be they a student seeking education, a skilled worker looking for new opportunities or a mother and child fleeing civil war. In this book I hope to provide a deeper understanding of what makes a person leave their native land, often in extreme difficulty, in order to start a new life abroad. Each of these fourteen stories are completely different; some came to Ireland for work; others for education; some retired here; others fell in love with an Irish person. Some came here out of necessity, forced from their homes by death and destruction. But they all have one thing in common: they are all migrants.

Interspersed between these personal stories—which run chronologically from the enlargement of the European Union in 2004 to the inauguration of Donald Trump in 2017—I offer the reader a brief snapshot, year by year, of the context behind them: the mass migration of people across national boundaries in search of a better life, which is one of the defining issues of our globalised age. This is not an in-depth or academic study. It is one Irish journalist’s view, based on interviews with individual actors in this great drama; the drama of what Ivan Krastev, the Bulgarian political scientist, has called the ‘revolution’ of the twenty-first century.

Migration is not a new phenomenon—we humans are migratory creatures. But in this technologically advanced era, the migrant crisis of recent years has been broadcast to a worldwide audience. People can no longer turn a blind eye to the crises unfolding on the borders of Greece or Lebanon, Mexico or Bangladesh. Awareness is just a click away through Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. However, understanding and empathy require greater effort. These stories are my small contribution to enhancing this empathy so that, like my great-grandparents in County Antrim all those years ago, our nation has the confidence and compassion to open our doors and truly live up to our reputation as the home of céad míle fáilte.

2004 Migration

On Saturday 1 May 2004, Irish Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney stood on the steps of Farmleigh House in Dublin’s Phoenix Park and read his poem ‘Beacons at Bealtaine’. Written specially for the European Union enlargement celebrations, Heaney’s poetry captured the palpable sense of achievement and possibility that filled the air that bright sunny Saturday as leaders from twenty-five member states gathered in Dublin to celebrate the expansion of the EU project. On that day, the European Union, which had begun as just six countries—Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands—spread east to incorporate ten new nations into its political and economic alliance. Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia were welcomed into a project which began in 1950 with the goal of ending centuries of war and bloodshed in Europe.

The Union, which had grown from 6 to 15 member states over the latter half of the twentieth century—including the accession of Ireland with Denmark and the United Kingdom in January 1973—sought to achieve a society where inclusion, tolerance, justice, solidarity and non-discrimination would prevail. An Irish Times editorial published on 1 May noted that enlargement was

‘the greatest achievement of the EU’s foreign policy, bringing peaceful transformation to most of Europe at a time when the Balkan wars pointed up the danger of different outcomes. For most of the new EU member-states, today’s events represent a final liberation from that Soviet and communist tyranny—even though they have exchanged incorporation in one form of international union for another. The central difference is that the EU is a voluntary union of states whose equality is legally recognised.’1

It is clear that 2004 was a time of great positivity and optimism for the European Union. Nearly a decade had passed since the Balkans conflict and the barrier that once divided the continent between communist east and capitalist west was becoming a distant memory. While the 2003 Iraq war had arguably triggered a divide across Europe between those who supported or rejected armed intervention in that conflict, the freedom, democracy and protection of human rights promised by the Union seemed increasingly achievable.

The Irish State, which held the EU presidency at the time of enlargement and was in the middle of an economic boom, was eager to invite central and eastern European job seekers into the country to help with the rapid expansion and growth of twenty-first century Ireland. The many workers who began arriving on Irish shores during the summer of 2004 from Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and other central and eastern European countries were for the most part welcomed with open arms into the construction, hospitality, agriculture and retail industries.

John O’Brennan, a lecturer in European politics at the National University of Ireland Maynooth, later wrote that between 2002 and 2012, ‘the UK and Ireland proved amongst the most favoured destinations for new member state nationals, not just because of the attractive employment prospects they offered, but because English is now unquestionably the dominant language in a world of technologically driven globalisation’.2

The results of the 2002 Irish census showed that the Polish presence in the Republic was nearly non-existent with just 2,124 Poles recorded in April of that year. The census, carried out just over two years before EU enlargement, also showed there were just 2,104 Lithuanians and 1,797 Latvians living in Ireland. By 2006 the number of Poles had skyrocketed to 63,276, while the number of Lithuanians had risen to 24,468 and Latvians to 13,319.

In 2002 the number of immigrants from countries outside Europe was slightly higher than arrivals from eastern European nations, but still relatively low when compared with later statistics. The census of that year found 8,969 Nigerians, 5,842 Chinese, and 4,185 South Africans living in Ireland. By 2006 there were 16,300 Nigerians and 11,161 Chinese people in Ireland, with just a small rise to 5,432 for South Africans.

While the initial response to this rise in immigration was positive among many Irish people, a fear of different races, cultures and beliefs did begin to gradually spread among some communities. This distrust was bolstered by rumours that many of the women arriving from African countries were pregnant and came with the sole aim of ensuring Irish citizenship for their newborn child. The response from the Irish Government, or more specifically Minister for Justice Michael McDowell, was to hold a referendum to change the rules around the constitutional entitlement to citizenship by birth.

McDowell described people coming into Ireland to give birth to children and secure Irish citizenship as ‘citizenship tourists’, but rejected claims that the vote was racist. Taoiseach Bertie Ahern also rejected suggestions that the referendum would undermine the human rights of children born in Ireland. The Labour Party, which opposed the change to the constitution, warned the referendum would ‘encourage racist tendencies’. Michael D Higgins, who was Labour party president at the time, described McDowell’s proposal as ‘shameful and disgraceful’ and said he could not accept a change that would mean two children born in the same maternity ward on the same day would enjoy different legal and constitutional rights.

The referendum was held on 11 June 2004 and passed with an overwhelming 79.17% voting against giving Irish citizenship to every child born in Ireland. Under the new legislation, Irish citizenship could only be granted to children with at least one parent who was an Irish citizen, or entitled to Irish citizenship, at the time of their birth. Before 1999 the right to citizenship by reason of birth in Ireland had existed in ordinary law. Automatic entitlement to Irish citizenship at birth had been in place since a constitutional amendment in 1999 which stated: ‘It is the entitlement and birthright of every person born in the island of Ireland, which includes its islands and seas, to be part of the Irish nation.’ This birthright ceased to exist on 1 January 2005.

Dr Aoileann Ní Mhurchú, lecturer in international politics at the University of Manchester, later wrote that automatic citizenship at birth was almost universally associated as ‘a more inclusive way of regulating citizenship than that of citizenship by descent’. Ní Mhurchú argued that birthright citizenship was necessary for integration and to ‘ensure that illegality is not passed down through generations of migrants’.3

As the Irish citizenship debate continued throughout 2004, international fears of terrorist activity in Europe began gaining momentum after a series of bombings in Madrid. On 11 March 2004, 192 people died and more than 2,000 were injured when ten bombs packed with nails and dynamite exploded on four trains heading into central Madrid. It later emerged that the bombings had been carried out by a group of young men, mostly from north Africa, who according to prosecutors were inspired by an Al-Qaeda affiliated website that called for attacks on Spain.

The previous year the Spanish conservative government had strongly backed the American invasion in Iraq despite polls that showed more than 90% of Spaniards were opposed to intervention. It was felt by many that the 2004 Madrid bombings were a response from Islamic militants to Spanish involvement in the Iraqi conflict and a warning message to the rest of Europe that it too could fall victim to terrorist activity if it embraced the American war effort.

Despite the growing antagonism and divergent opinions among European member states over whether or not involvement in the Iraq war could trigger future terrorist attacks, EU leaders still pushed ahead with the enlargement celebrations in Dublin that May. Highlighting the achievements of the Union, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern called on attendees to remember that ‘from war we have created peace, from hatred we have created respect, from division we have created union, from dictatorship and oppression we have created vibrant and sturdy democracies; from poverty we have created prosperity.’4

Bassam Al-Sabah, 2004

Whenever Bassam Al-Sabah mentions in conversation that he spent the first decade of his life in Iraq, he nearly always detects a note of pity in people’s response. ‘I feel like they don’t know how to react to that information. I think people are interested but they also don’t want to get too political. It’s like someone who hasn’t come from that background feels they should respond in a certain way. But for a person who is actually from Iraq, you just lived there. There’s no pity about that for us. It was our life.’

In fact, when people ask where he comes from, Bassam prefers to say Balbriggan rather than Ireland or Iraq. ‘It depends on how the person asks the question but it’s often very like “oh, I see you’re not from here, where are you actually from?” I say Balbriggan because I like seeing the confusion on their faces. It’s this moment of “wait, but you don’t look Irish. What?” Sometimes I forget I look different and that question is a reminder that for many Irish people you are different. Most of the time it’s not out of malice that people ask these questions, they’re just interested. But at a certain point I do just say I’m from Iraq, it’s easier.’

Rather than talk about his Iraqi heritage, Bassam prefers using his artistic talents to reflect on the childhood he spent in a country that since the mid-2000s has become synonymous with war and violence. In 2016, following his graduation from the Dún Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design and Technology (IADT), the young artist was selected as one of the thirteen best graduating artists in Ireland and awarded a place to exhibit at the RDS visual art awards. He was also the recipient of the Royal Hibernian Academy 2016 graduate award which gave him the use of a studio at the RHA in Dublin for a year.