Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Winner of the National Book Critics Circle John Leonard Prize Winner of the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize A boy unearths a jar that holds an old curse, which sets into motion his family's unravelling, a man, while trying to swindle some pot from a dealer, discovers a friend passed out in the woods, his hair frozen into the snow, and two friends, inspired by Antiques Roadshow, attempt to rob the tribal museum for valuable root clubs. Night of the Living Rez, the book that heralded the arrival of a standout talent in contemporary fiction, is an unforgettable portrayal of an Indigenous community.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 382

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘As I got deeper into the work, into the book, and came to understand these lives and this community, the more familiar it felt – our Native communities being bound by countless common threads, strengths and afflictions both – and only then did I understand the distinct brilliance of Talty’s voice as its own, and ours. I knew and felt for these people. Wanted to and knew I couldn’t help them, even as they did me. There is so much brutal, raw, and beautiful power in these stories. I kept wanting to read and know more about these peoples’ lives, how they ended up where they ended up, how they would get out, how they wouldn’t. It is difficult to be so honest, and funny, and sad, at once, in any kind of work. Reading this book, I literally laughed and cried.’

TOMMY ORANGE

‘These stories are profoundly moving and essential, rendered with precision and intimacy. Talty is a powerful new voice in Native American fiction.’

BRANDON HOBSON

‘Night of the Living Rez is a fiercely intelligent and beautifully written set of stories . . . Morgan Talty is a master of the way dependency and pain transition from one body to another; the way both separating and refusing to separate become modes of saving ourselves; and the way, for all of our failures, we never stop doing what we can to provide each other hope.’

JIM SHEPARD

‘Night of the Living Rez is true storytelling. It’s a book so funny, so real, so spirited and vivid it brought me back to my own rez life and the people who made me.’

TERESE MARIE MAILHOT

‘While soaked in pain and broken promises, Night of The Living Rez delivers with grace and dignity . . . Talty proves that this is why Indigenous Literature continues to be its own unique and sacred blessing. I loved this book. Mahsi cho, Morgan!’

RICHARD VAN CAMP

‘An indelible portrait of a family in crisis, and an incisive exploration of the myriad ways in which the past persists in haunting the present. I loved these sharply atmospheric, daring, and intensely moving stories, each one dense with peril and tenderness.’

LAURA VAN DEN BERG

‘Remarkable . . . an electric, captivating voice. . . . Talty has assured himself a spot in the canon of great Native American literature.’

NEW YORK TIMES

‘Memorable.’

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

‘Flawless . . . a masterwork by a major talent.’

STAR TRIBUNE

‘A perfect mix of funny, sad, timely, and intense, this one has something for everyone.’

BOSTON GLOBE

‘Talty’s book haunted and thrilled me in its raw explorations of inheritance, grief and survival, imbued with humour and warmth.’

NPR BOOKS

‘Gorgeous.’

COSMOPOLITAN

‘A blazing new talent.’

OPRAH DAILY

‘Remarkable.’

MS. MAGAZINE

‘Searing, devastating and often darkly funny.’

GOOD HOUSEKEEPING

‘Ingenious . . . Unforgettable.’

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY, STARRED REVIEW

‘Talty is adept at unearthing his characters’ emotions . . . Ranging from grim to tender, these stories reveal the hardships facing a young Native American in contemporary America.’

KIRKUS, STARRED REVIEW

‘Brilliant.’

FOREWORD REVIEWS, STARRED REVIEW

‘Remarkable . . . Clear-eyed and compassionate.’

BOOKLIST

‘Tender, searing insight tempered with humour and compassion. This is a book to sink into.’

THE RUMPUS

‘A masterful debut . . . filled with grit and has heaps of heart to spare.’

ELECTRIC LIT

‘It’s so damn good. After reading the last sentence of the final short story, I just sat there feeling stunned.’

THE MILLIONS

‘Powerful.’

BUZZFEED

‘Woven together with the care and intimacy of a family heirloom.’

CHICAGO REVIEW OF BOOKS

‘An inspired debut.’

DAILY BEAST

Night of theLiving Rez

First published in the UK in 2025 by And Other Stories

Sheffield – London – New York

www.andotherstories.org

Copyright © Morgan Talty 2022

All rights reserved. Morgan Talty has asserted their right to be identified as the author of this Work.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

ISBN: 9781916751187

eBook ISBN: 9781916751194

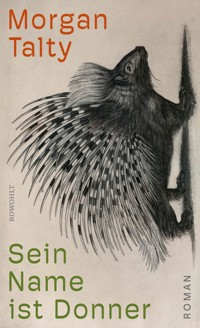

Offset by Tetragon, London; Series Cover Design: Elisa von Randow, Alles Blau Studio, Brazil, after a concept by And Other Stories.

And Other Stories books are printed and bound in the UK on FSC-certified paper by the CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

And Other Stories’ Authorized Representative within the EU GPSR legal framework is: Logos Europe, 9 rue Nicolas Poussin, 17000 La Rochelle, France. (Logos Europe do not represent to publishers the rights to this title.) E-mail: [email protected]

And Other Stories gratefully acknowledge that our work is supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

CONTENTS

BURN

IN A JAR

GET ME SOME MEDICINE

FOOD FOR THE COMMON COLD

IN A FIELD OF STRAY CATERPILLARS

THE BLESSING TOBACCO

SAFE HARBOR

SMOKES LAST

HALF-LIFE

EARTH, SPEAK

NIGHT OF THE LIVING REZ

THE NAME MEANS THUNDER

A NOTE ON PENOBSCOT SPELLING

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For Mom (1959-2021)

And for all the women who raised me

BURN

Winter, and I walked the sidewalk at night along banks of hard snow. I’d come from Rab’s apartment off the reservation. Rab—this white guy with a wide mouth and eyes that closed up when he laughed—sold pot. He was all no-bullshit too. I had asked for a gram, and after he weighed it and put it in a plastic baggie and held it out to me, I reached into my pants and jacket pockets looking for the cash among the cigarette wrappers and pocketknife, and he didn’t believe me as I acted the part and kept saying, “Shit shit shit, it must’ve fell out on the walk over here.” He shook his head, took the weed out of the baggie, and put it back into his mason jar. “I ain’t smokin’ you up,” he said, and so then I said, “Fuck you, Rab, I really did lose the money, you’ll see, watch when I come back here in thirty minutes with the money I dropped, you’ll feel stupid then.” He shrugged a Sorry, man, and I slammed his door shut as I left.

At the bridge to the reservation, the river was still frozen, ice shining white-blue under a full moon. The sidewalk on the bridge hadn’t been shoveled since the last nor’easter crapped snow in November, and I walked in the boot prints everyone made who walked the walk to Overtown to get pot or catch the bus to wherever it was us skeejins had to go, which wasn’t anywhere because everything we needed—except pot—was on the rez. Well, except Best Buy or Bed Bath & Beyond, but those Natives who bought 4K Ultra DVDs or fresh white doilies had cars, wouldn’t be taking the bus like me or Fellis did each day to the methadone clinic. That was another thing the rez didn’t have: a methadone clinic. But we had sacred grounds where sweats and peyote ceremonies happened once a month, except since I had chosen to take methadone, I was ineligible to participate in Native spiritual practice, according to the doc on the rez.

Natives damning Natives.

The roads on the rez were quiet, trees bending under the weight of snow, and when I passed the frozen swamp a voice moaned out. I stopped walking. Nothing, so I kept on going on the sparkling road until I heard it again.

“Who’s that?” I yelled. The moan came again. It was a man, somewhere in the swamp. I got closer, listening. There it was: a low and breathy noise, and with my cold ear I followed it.

The swamp was frozen solid, the snow blown in piles, and so I slid over the ice, looking for the source of the noise. Moonlight through bare tree limbs lit the swamp, and caught among the tree stumps and solid snow was a person sprawled out on the ground. He was trying to sit up but kept falling back, like he’d just done one thousand crunches and was too sore to do just one more.

It was Fellis.

“Fellis?” I said, standing over him.

He tried to sit up, but something pulled him back down. “Fuck you,” Fellis said. “Help me.” He groaned, shivered.

He didn’t say how to help him, so I had to squat down to get a better look. I flicked my lighter and his purple lip quivered.

“Hurry,” he said.

“Fellis, I can’t help you if I don’t know what’s a matter with you.”

“My hair,” he said.

I looked at it with the lighter’s flame. “Holy,” I said, and I laughed. Instead of the tight braid that shined, Fellis’s hair had come undone, and it was frozen into the snow.

“Get me out, Dee,” he said. “Dee, get me out.”

At first I tried to pull the hair out from the snow, tried to chip the snow away. But his hair wouldn’t come loose, so I yanked, and Fellis screamed.

“Lift your head up,” I said. I opened my pocketknife, and at the click of the blade Fellis spoke.

“Wait, wait,” he said. “Don’t cut it.”

“What do you want me to do? Tell the ice to let go?”

Fellis spit. “Go to my house and get boiling water.”

I closed the pocketknife. “Fellis, by the time I got back here the water would be chilled.”

He was quiet. As if something walked around or among us, the ice cracked and echoed somewhere in the swamp. The moon shone bright, and I looked. There was nobody but us.

“I have to cut it,” I said. “You ain’t getting out if I don’t.”

Fellis asked if I had a cigarette, and when I told him no, he cursed. “Fucking bullshit, fucking goddamn winter, what the fuck.”

I laughed.

“It ain’t funny, Dee.”

“Look,” I said. “You want me to cut my braid too?”

Fellis took a deep breath, and he coughed and gagged. “No,” he said. “Just cut it. I gotta get home. I’m sick.”

I opened the pocketknife again, grabbed his hair in a fistful, and cut. When I got through the last bit of hair, Fellis rolled over and away from where he’d been stuck. He rubbed his head like he just woke up.

I helped him stand, and we slipped all over the ice on our way out of the swamp. Through dry heaves, Fellis said he’d missed the bus this morning to the methadone clinic—“No shit,” I said, because I didn’t see him on the bus or at the clinic—and he thought some booze would be good before he got sick from not having any methadone. He’d had a bit of booze left that afternoon when he decided to go see Rab to get some pot, and on the way he’d stopped off in the swamp to feel the quiet that came with too much drinking, and when he plopped down in the snow he’d dozed right off. When he woke up, his hair was frozen in the snow.

I got him to his mom’s, Beth’s, where he still lived. He walked fine by himself to the door, but I walked with him up the steps.

“I never thought I’d scalp a fellow tribal member,” I said.

“Fuck off,” he said. He fumbled in his pocket for his house key.

“You wanna smoke?” I said.

“Didn’t you listen? I didn’t make it to Rab’s.” He unlocked the door.

“I’ll go for you,” I said. “Give me the cash.”

Fellis looked at me.

“Twenty minutes,” I said. “I’ll run there and back while you warm up your pretty bald head.”

He gave me thirty bucks, and I didn’t ask where he got it from. Yesterday he said he didn’t have any money.

“Twenty bag,” Fellis said. “And stop at Jim’s and get some tall boys and a bag of chips. Any kind but Humpty Dumpty chips.”

Down Fellis’s driveway I imagined the look on Rab’s face when I gave him the money. What I tell you? How about that gram?

“Dee!” Fellis yelled. “One more thing. Bring me my hair, so we can burn it. Don’t want spirits after us.”

“We’re damned anyway,” I said. “But I guess I’ll get your hair.”

I kept going, wondering, Hair or pot first? Pot made the most sense. It would look strange having to set the hair and ice down like a soaked mop on the counter at Jim’s while I reached in my pocket for Fellis’s money. Jim—that old wood booger—would say, “We don’t take those anymore.” I’d look him square in his sagging face and say, “I ain’t trading no hair, you old fucker,” and I’d smack down on the counter a ten-dollar bill for the tall boys and chips. With the change jingling in my pocket, I’d walk to Rab’s and he’d say, “Get that hair out of here, it’s dripping on my floor,” and I’d have to plop the hair on the muddy white floor in the hallway while Rab reweighed the same nugs he’d weighed for me earlier.

No. I’d grab Fellis’s hair from the swamp on my way home. With Fellis on his unmade bed, me on a torn beanbag in the corner, each of us with a tall boy and the pot smoke hazing gray the room, we’d keep poking and squeezing the hair, waiting for it to dry, waiting to burn it.

IN A JAR

I no longer had a fever, but Mom worried I was still sick and told me to take it easy. All throughout my first morning in our new home, she sat me on the couch with a bowl of cereal and half a piece of toast while she unpacked and fixed up the whole house, nailed her brown shelves to the white walls, and spread out atop the shelves all her colored knickknacks, miniatures of larger things like wooden bowls filled with wooden painted fruit, tiny glass soda bottles, little porcelain turtles, and a set of tiny, tiny books with real pages, all blank. When my food was gone, I sat wondering about Mom’s hair. She had gotten a haircut, and I had no idea how she had time to get one. When she finished with the house, we went outside, where I sat on the concrete steps and played with my toy men, the ones I kept in a black plastic tub and the ones my father bought me each time he returned from the casino. I had a lot of toy men. As I played, Mom worked in the shed. She organized and stacked extra boxes from our move to the Panawahpskek Nation. Maybe move was not the right word. All I knew was that we left our life down south with my father and sister. I had asked countless times, but Mom never said if Paige was coming.

I wasn’t at play long before I lost one of my men to a gap between the stairs and the door. It was a red alien guy, and although he wasn’t my favorite, I still cared. Looking behind the steps, my knees were wet when I knelt in the snow, and my hands were cold and muddy when I held myself up. The sun beamed on my neck, and a sliver of sunlight also shone behind the concrete steps, right at the perfect angle, and in the light I thought I saw my toy man. But when I reached for him I grabbed hold of something hard and round. I pulled it out.

It was a glass jar filled with hair and corn and teeth. The teeth were white with a tint of yellow at the root. The hair was gray and thin and loose. Wild. And the corn was kind of like the teeth, white and yellow and looked hard.

“Mumma,” I said. “What is this?”

“David,” she said from inside the shed. “Can you wait? Please, honey.”

I said nothing, waited, and examined the jar. My hand was slightly red from either the hot glass sitting in the sun all afternoon or the cold snow I crawled on.

Mom came out of the shed, squinting in the light.

“What’s what, gwus?” she said. Little boy, she meant.

I held the jar to her and she took it. I watched her look at it, her head tilted and her brown eyes wide as the jar. And then she dropped it into the snow and mud and told me to pack up my toys. “No, no, never mind,” she said. “Leave the toys. Come on, let’s go inside.”

She got on the phone and called somebody, whose voice on the other end I could hear and it sounded familiar. “I’ll be by,” he said. “I can get there soon. Don’t touch it, and don’t let him touch anything.”

Mom hung up the phone and lit a cigarette.

We waited for a long while. Mom stayed quiet, and with no talk or toy men to occupy myself with, I tried to remember the move to our new home, which was not some faraway memory and was only a day back. But because of the fever, I remembered only fragments. Miles of highway, miles of pine trees. I remembered riding in the front seat of our white Toyota as I burned up. Mom had held her long Winston 100 up to the cracked car window, and at eighty miles per hour the passing air sucked the smoke out. “We left Paige,” I kept saying. “We left her, Mumma.” Mom took her eyes off the road and looked over at me. She held her hand to my sweaty forehead. “You poor thing,” she said. Mom had driven fast. Real fast, and she watched me most of the time during the drive, as if I had been her road the whole way to our new home.

Mom’s voice startled me. “Stop biting your fingernails,” she said. She lit a second cigarette while we continued to wait. “He said not to touch anything—that includes your mouth.” For quite some time I tried to remember our arrival, tried to find the exact memory of my mother putting together a bed, making it, and putting me under the blankets. But I couldn’t remember any of that. All I remembered was that at one point the night before I had a dream where I crawled out of bed and into the darkness of the unfamiliar house, and I grabbed at a doorknob that wasn’t there, tripped over boxes that cluttered the short and narrow hallway that led straight to the kitchen and small living room where a man’s voice spoke to me, telling me to go back to bed. I’d asked who he was but he didn’t answer. He guided me back to my room, his boots echoing down the hallway.

At the noise of a truck and its engine cutting off, Mom said, “Finally,” and she stood from the table. When the man came down the driveway and up the stairs and stepped over that gap, I knew at once it hadn’t been a dream. The man Mom called about the jar was the man who put me to bed last night. He was dark like Mom, and unlike Mom he had long black hair, and little black whiskers on his upper lip. He wasn’t fat, but he had a pudge to him I hadn’t noticed in the dark, and his jeans were faded and baggy. He wore a red-and-black flannel button-up.

“Gwus,” Mom said. “This is Frick. He’s a medicine man.”

“He was here last night,” I said to Mom, and then to Frick I said, “I saw you.”

“Who do you think hooked up the woodstove?” Frick asked.

I thought Mom.

“Let me see your hand,” Frick said.

I held my hand out to him and he took it and rubbed my palm. He let go and talked to Mom about the jar. “It’s bad medicine,” he said, and Mom wondered who would put it here. Frick had no answer. “Could have been anyone on the rez. I’ll take care of it.”

He left the house. I wondered why you couldn’t throw it away, wondered how Frick would handle it. I asked Mom, and she got all annoyed.

“You can’t throw it away,” she said. “Frick’s a Native doctor. It needs to be properly disposed of.”

I asked why again, and she said that what I’d found had been meant to hurt me. To hurt us.

“But I feel fine,” I told her, to which she said, “Just in case.”

Soon Frick opened the door and said he was ready for us. Mom took me outside and to the back of the house and down into the woods where a tree had four cloth flags hanging: red, white, black, and yellow.

“It’s the four directions,” Mom told me.

“What’s it for?” I said.

“It’s to heal us.”

“But my fever’s gone,” I said. “I’m not sick.”

“Yes you are,” she said.

Frick knelt in front of the tree with the four flags, and he was mumbling words in skeejin. It was strange hearing another person use skeejin besides Mom and Paige and Grammy, when Grammy would come to visit. But I couldn’t hear what he was saying, and I still couldn’t make out the words when smoke rose around him and he stood holding a giant seashell the size of a baseball glove filled with tobacco and this long, thick, bushy thing I’d later learn was sage that burned and smelled calm, like salt water.

In his hand he held a giant feather—eagle, Mom said—that was beaded at the quill. He moved toward us, still mumbling, and Mom said he was praying. “He’s smudging us. It’s good medicine. Watch how I do it, gwus.”

Frick stepped forward and tripped over a hard root and he dropped the smoking sage.

“Shit,” he said.

I laughed, and Mom let out a sharp shush and I shut up.

Frick picked up the sage among the soft mud and melting snow and he walked and stood in front of her. He had to relight the sage. The smoke rolled up and around him, and with the feather he brushed the smoke over my mother. He started on her head, pushed the smoke with the feather over her and through her short hair, and then he moved the smoke to her chest. She turned around, and he did her back. She turned around, facing him, and she lifted her arms. His face looked serious. He smudged under her arms and in her armpits. Then down her legs. Mom lifted her feet and Frick pushed the smoke under her. He stepped away from her, and he mumbled a few more words, returned to the tree with the four flags, which blew in a slight breeze, and then he knelt again and spoke more words louder. He stood and then smudged me over in the same way he had my mother.

When he finished, he smudged my toys, too, and the steps and the back door. Then in the house he smudged everything, and I watched our home fill with a burning fog. I coughed once. He finally finished and returned to the tree out back while Mom and I sat at the kitchen table.

In time, Frick came through the door, and in his hand he held something red. At first I thought he’d gone behind the steps and got my plastic alien figure, but then I realized it wasn’t my toy. It was thin yellow straw, wrapped in a red cloth bound in twine.

“Can you get me a wall tack?” he said to Mom, who got up and dug through a kitchen drawer yet could not find one. She went to the empty bedroom that I hoped Paige would soon fill and came out and handed a tiny green tack to Frick. He pinned the yellow straw in red cloth above our door. “It’ll keep bad medicine out,” he said to Mom and me. “Also, I have this.”

He dug in his pocket and pulled out a small deer-hide pouch that was sewed shut. It was no bigger than a quarter, and an open safety pin stabbed through the middle.

“Come here,” he told me. I stepped forward, and he knelt on one knee. Clenching the pouch, he stuffed his hand up my shirt, and in front of my heart, he stabbed the pin through the cotton and clamped the pin shut.

“Can I have one?” Mom said, and Frick pulled another from his pocket. Mom took it and pinned it on.

“It’s a medicine pouch,” Frick said. “I made it.”

“How does it work?” I asked.

“It just does,” he said.

The pouch was itchy, and I didn’t care for it. I planned to take it off and stuff it under my bed the moment I was back in my room. At least what he hung and pinned above the door wasn’t physically bothersome. Distracting, certainly—it looked like a toy, the way it was wrapped in that red, and every time I walked down the hallway or when I left the house I thought of my lost plastic guy who was getting sucked deeper and deeper into that thawing mud.

. . .

It seemed that Frick had moved in just as fast as Mom had unpacked the whole house. He’d be there all day, sitting with her on the couch or at the kitchen table, and he’d be there when I went to bed, both of them drinking wine from a box. In the morning, he drank black coffee and smoked cigarettes with Mom. Soon his hairbrush was in the bathroom, strands of hair floating unflushed in toilet water, and his toothbrush was in a cup next to mine.

I had heard Frick say the jar was an old curse, and most likely not done right, that some skeejins were messing with Mom and me, but it had been best to be safe and pray and smudge and bless the home.

I felt fine, even before the smudge when I had held that jar, so I agreed with Frick that it probably wasn’t done right, but Mom wasn’t so sure. “I don’t know,” she kept saying, not really to me, but to Frick, who would shake his head. “Only time will tell,” she said.

At the end of March, I started up at school, and after school I spent the afternoons until dinner at the community center—rusted roof, yellow walls—playing basketball on the concrete floor with some of the kids in my class, and it took no time falling into that place, feeling that I had been there my whole life and that I’d not been plucked out of my bed in the middle of the night with a fever and driven way, way north to where Mom had grown up.

If Dad was mad about our disappearance he never said anything to me, but I heard Mom fighting with him on the phone late at night, and one time I heard Frick get on the phone and yell at him. “You gamblin’ man,” Frick had said. He slurred his words. “You lost a big hand.” On the nights I heard them on the phone, I often fell asleep dreaming of my lost alien figure behind the steps.

I talked to Dad after dinner almost every night, and he always asked the questions Mom never asked: “How was school?” “What’d you have for breakfast?” “What’d you have for lunch?” “What’d you play today?” “Get any homework?” “What’s your favorite subject there?” Sometimes he’d say he’d send me up a toy. “When this next job goes through I’ll send you up that spaceship.” He always gave me some hope about something, and when I’d forgotten about the toy and moved on, some small action figure would show up FedEx on our slanted concrete steps and then make its way into my black plastic tub with all my other men. The tub was getting full, the lid barely able to click shut.

. . .

For months, Mom mentioned the jar at least once a day. “There’s something about it,” she’d say. “I don’t think we’ve seen the last of it.” Eventually Mom stopped talking about it, because Frick told her to, but then she brought it back up again at the end of the summer when the air got sharp cold at night and Paige showed up in her tarnished Volkswagen. I’d heard the car before I saw it, heard the way the engine whistled and then thumped when she drove it in first gear. Mom and Frick were sitting at the kitchen table drinking wine from a box in hard plastic cups. I ran down the hall and into the kitchen and past Mom and Frick drinking and flung open the door.

“I told you she’d come,” Mom said. I was so happy Paige arrived that I didn’t even care that Mom lied: she hadn’t said Paige would come.

In bare feet, I ran over the sandy sharp-pebbled driveway to Paige and hugged her waist and she hugged me back, ruffled my hair, and kissed the top of my head. “You got taller, you know that, chagooksis?” Chagooksis. Her little shit.

“Well your ears still stick out,” I said. She made a face, wrinkled her nose at me, and then kissed the top of my head again.

Inside, Mom hugged Paige hard, and Frick stood, shook her hand. Paige didn’t say anything to Frick, and after he left I realized Mom hadn’t said anything to Paige about him. I was sitting on the couch, eating an Italian ice and watching The Simpsons. Mom and Paige were smoking cigarettes at the kitchen table, and whenever a commercial came on I listened to them.

“Who even is that guy?” Paige said.

“Frick,” Mom told her. Since Mom was young when she’d had Paige—they shared a closeness—Paige had a way of getting Mom to open up, be something other than a mother. Sometimes, when Paige was around, I wondered if Paige wasn’t in fact my mother’s sister, given the way they spoke to each other and the way they fought and the swears they flung toward one another.

“Frick?” Paige said. “What the fuck is a Frick?”

Mom laughed. “His name’s Melvin, but everyone says when he’s drunk he’s always saying, ‘fricken this, fricken that.’”

“Does he?”

Mom’s lighter flicked. “Does he what?”

“Say fricken when he’s drunk?”

Mom was quiet, thinking. “Yeah, I guess he does.”

“He’s weird,” Paige said. “He didn’t even talk when I got here. He shook my hand and then sat back down, didn’t even say anything else and got up and left.”

“Oh, he’s just shy.”

“If you say so.”

Mom pushed her chair back and the legs squeaked against the floor. I heard the fridge door open. “Gwus,” she said. “You want something to drink?”

I told her no, and then she asked Paige if she wanted a cup of wine. I stared at the television as Homer choked Bart, Bart’s pink, worm-looking tongue flapping in the air, and I was laughing and laughing all by myself, my empty plastic cup of Italian ice bobbing up and down on my belly. And then a commercial came on and I stopped laughing and there was this moment of immense silence, and then Mom was on Paige like Homer on Bart.

“Whose is it, Paige? Huh?” Mom was yelling.

“Would you calm down?”

“I ain’t going to calm down.” She slammed her plastic cup down. “That’s why you come up here, isn’t it? You little bitch. Little bitch!”

I peeked around the corner and into the kitchen, and Mom was standing over Paige, and then Paige stood and leaned into her, yelling back, cursing, pushing her with her body.

This was nothing new—the racing heart—but I still panicked and screamed and slapped the wall. “Stop it!”

Mom didn’t look at me. “Go to your room, gwus. Right now.”

I hurried down the hallway, Mom’s words buzzing in my head, and I heard Paige before I shut my door: “He’s going to grow up to hate you too.”

. . .

I stayed in my room, playing with my plastic men, while they fought with low voices over the running kitchen-sink faucet. Mom slammed plates and cups and silverware while she did the dishes. Half the time that was how she washed dishes. Every so often Paige’s laughter hit my ears and I knew it made Mom angrier and angrier. After about an hour, the house was quiet. But that they weren’t talking didn’t mean the argument was over.

I put my plastic men away and opened my bedroom door, crept down the hallway into the kitchen. Mom was wiping the kitchen counters and the back door was open, and through the screen door I saw Paige outside on the steps, smoking, her knees pulled up to her chest.

“Boy,” Mom said. I stood still. There was one word that told me Mom’s mood, and that was the word. Boy. There was something about it, the way she’d call me gwus—which meant boy—or the way she called me boy. Maybe it was the tone she said it with.

“Boy,” she said again. “Go tell your sister that smoking’s bad when you’re carrying a child.”

“Go tell her?” I said.

“You heard me.” She scrubbed the stovetop, which shook the burners, a rattling metal. She tossed the rag down and picked up her plastic cup and finished what had been in there. She went to her room.

Through the screen door I said, “Paige?”

She didn’t look at me. “I know, David. Go watch TV.”

Mom didn’t come out of her room for the rest of the day, and Grammy showed up after Paige cooked me dinner. Grammy always popped up unannounced, and on more than one occasion Mom would see Grammy pull in the driveway and would shut all the lights off and take me to her room and tell me to be quiet, that she didn’t feel like visiting that day, and I had to sit there on the itchy carpet with her and listen to Grammy knock and knock and knock, and I imagined she was putting her face to the little window on the door, looking in, looking for us. “We went for a walk” was what Mom always told Grammy when she saw her next.

The door was open, and so Grammy came in. I hopped off the couch. “Hi, son,” she said. I gave her a hug. Paige turned off the sink faucet and dried her hands.

“When’d you get here, doos?” Grammy said to Paige.

“A little while ago.”

Grammy walked over the linoleum with her shoes on and gave Paige a hug that said It’s nice to see you. “Where’s your mom?” she said.

“She’s not feeling well.”

Grammy looked up the hallway.

“Something she ate,” Paige said.

Grammy said, “Mm-hmm.” She stood in the doorway, and Paige asked if she wanted to sit down. “No, no,” Grammy said. “I was coming to see if David wanted to go to the evening service at the church.” She looked at me, and in looking at me I was compelled to say yes. She was my Grammy after all. But I didn’t want to go alone with her, not because of her but because it was church.

“I’ll go if Paige goes,” I said. Paige dropped her head and shoulders, shook her head. She went to her bedroom and changed.

Grammy’s car was a puttering, two-door piece of rusted metal. I’d thought Paige’s car was bad, but Grammy’s was something else. The engine made this whining sound every few minutes, like a bomb siren. Her turn signals worked, but on the dashboard it didn’t say if they were on or off, so sometimes she drove with her turn signal on for miles. Maybe she knew; maybe she was messing with other drivers. Also, the radio turned on and off by itself, and after we drove in silence past the small health clinic and the large tin-looking community building and the tribal offices tucked behind thick pine trees and the tan-brick school and the football field, we pulled into the church parking lot and the radio kicked on and blared out Meredith Brooks’s “Bitch,” and Paige bobbed her head, telling Grammy to turn it up, but she flicked the radio off.

“Michaganasuus,” Grammy said. This shitty thing.

We got out of the car, and Grammy hurried in front of us. Paige walked by my side and whispered about Goog’ooks. Evil spirits. “They follow Grammy around,” she said to me. “That’s why the radio turned on.”

I tried not to be scared, but I was. Paige always talked about Goog’ooks, and one reason why I never stayed at Grammy’s house was because Paige said it was haunted, and when I told Mom that, she said the whole Island was haunted, that years and years and years ago our people used this place as a graveyard, that even late at night she heard Goog’ooks tapping on the walls. Mom told me not to be scared.

In the church we took our seats, and I thumbed through the Bible in front of me. Other than that, I didn’t pay attention to anything, just watched people here and there, some with their eyes closed, some open. I didn’t think Paige was listening either—her head was turned sideways, eyes half open, like the priest’s Word was putting her to sleep.

After we’d lined up to receive the body of Christ—which I wasn’t allowed to ingest and instead received a pat on the head from the priest because Mom hadn’t had me baptized—we returned to our seats. Paige nudged me. Grammy watched, hand on her chest, as Paige broke her cracker in half and gave it to me. It dissolved in my mouth, and it tasted like a chalky cracker that had gotten wet and had dried again.

Paige saw the disgust in my face, and she whispered, “It’s the best Jesus could do.”

“Jesus made this?” I said.

Paige had her arms crossed. “I know, right?”

Grammy told us to shut the heck up.

Church dragged on. When we had to kneel, we knelt; when we had to sing, we sang; when we had to pray, we prayed. Grammy probably prayed for God to forgive Paige, and Paige probably prayed for a cigarette. Me, I prayed for the safe return of my alien figure in his red space suit. I still felt bad that he was all alone under those steps, buried in the cold mud, and I prayed that the change in seasons would churn him out to the surface, and I’d find him one day.

Toward the end of the service, we knelt one last time, saying one more prayer, but I didn’t pray for anything because I couldn’t focus: I smelled a stinky pigadee, a fart. I had my eyes cracked open, looking, and I felt Paige looking too. We made eye contact, and she leaned toward me.

“David,” she whispered, and she pointed at the upholstered cushioned wood we knelt on. “You ever wonder why they call this a pew?”

I puckered my lips, felt my face getting hot. I bit my tongue, using the pain to distract me from laughing. Grammy was looking at us, shaking her head, and it looked like she, too, was trying not to laugh, and when Paige saw Grammy’s face, Paige let out a little croak of laughter, loud enough for the priest to hear, loud enough to turn heads, loud enough for the person who ripped one to know they were caught.

. . .

Grammy dropped us off, reminded me once again that I could stay at her house anytime I wanted, and I told her okay. Frick was there, his truck pulled right behind Paige’s, but we didn’t see him or Mom. I walked down the hallway to my room, and I looked at the base of Mom’s door. There was no light. There were no voices.

I got ready for bed, put on my pajamas, and went to Paige’s room. I stood at her open bedroom door, trying to get her attention. She was lying in bed fully clothed still, head propped up with a pillow, reading the local Overtown paper with a cigarette between her fingers, the smoke clinging, rolling off the gray paper up to the ceiling. She moved the paper to the side and looked at me.

“Be-dee-gé, chagooksis,” she said. Come on in, little shit.

I crawled on her small bed, tried to roll over but elbowed her in her side. “Ow! Would you sit still?”

She read. Smoked. Flicked her cigarette. Read some more. Snubbed her cigarette. Lit a new one. Turned the pages, crinkled them. Finally, she lay the paper flat on her stomach, and it looked like a little mound but I knew it was her clothes making that bump, not the baby. Paige blew out an extra-long puff of smoke, and then was quiet.

The fridge in the kitchen hummed, and then it grumbled low like a stomach and clicked off. A pipe in the wall rattled. A minute of silence before the fridge started up again, humming, grumbling. Click. Another pipe. Silence. This went on until a different tapping began, gentle knocks down the dark hallway, over and up the walls. They got louder, closer, and Paige must have felt me grip her arm, because she said it was a pipe, but the knocking got louder, seemed to tap right on her bedroom door, and I knew there were no pipes in that thin hollow plywood.

Paige opened her eyes and looked. The knocking stopped, and I heard the fridge click on again and the floorboard heater ping, but then it all stopped again and the next thing I knew Paige jumped up, which sent me flying off the bed, and she screamed, grabbing her thigh.

Paige’s scream woke Mom and Frick, and Mom came out in her underwear and a long T-shirt, and Frick came out with his big brown belly hanging over his blue boxers, and in the light both Mom and Frick squinted.

“What the hell is the matter?” Mom said.

“Ow, shit!” Paige couldn’t roll up her black pants, so she pulled her pants down, and Frick looked horrified at her doing it, but then his eyes widened. I was grabbing Mom by the wrist, holding on to her, looking at Paige’s thigh. Something had bitten her—itty-bitty teeth marks.

“Move,” Frick said to Mom.

“Could it be the jar, Frick?” she asked.

Frick ignored her, got close to Paige, knelt and looked at the bite mark. Paige told Frick and Mom what we heard, the knocking, and then the silence, and then the pain she felt in her leg. I still gripped Mom’s wrist.

We were spooked, but Frick stayed calm. He went into Mom’s room and brought out a little bag made of deer hide, and he told Paige to go with him.

“Just stay inside,” Frick said to Mom and me. He still only had on his underwear, and I felt the chill come through the open door and nip through my pajamas. Mom and I sat at the kitchen table, and we were both in separate chairs. She was rubbing her head, and I asked her if she had a headache.

“A little bit, gwusis.”

They were gone for a long time, and then Frick opened the back door with Paige following him, the cold following her. Frick held the seashell bowl and smoke was coiling up and it swirled and blew away when he shut the door behind him and Paige. He smudged the whole house—especially Paige’s room—and then he smudged Mom and me.

When he finished, he blessed his seashell and tobacco and put it all back in the deer-hide bag. Mom didn’t say anything. She gave Paige a hug, kissed her good night, and then did the same to me, but told me to get to bed.

But I couldn’t sleep. All night I listened and listened for the knocking, which never came back, and I tried not to think about what it all was. What it all could be. At some point during the quiet night I got up and went to the floor and slid out from under my bed the black plastic tub, and when I pulled it out the medicine pouch Frick had given me dragged underneath the tub. Just in case it would help, I pinned the pouch to my shirt on the inside, and the pin pricked me. In the dark, I didn’t know if I was bleeding. I touched the skin, and it felt bloodless.

I opened the black plastic tub. I didn’t take out the men—I looked at them there, a pile of plastic bodies in the moonlight that shone behind me through the parted black curtains draped over the window. I realized that I’d have to get rid of some of the men, have to make room for new ones. What to do with the old toy men, the ones fading in color, their joints clogged with dried mud and crud? I thought about my father before I closed the black tub quietly and got back in bed. As the hours passed—as I dozed on and off—my room lit up with cold dawn light pouring through my window. I felt for the pouch, but it had fallen off. I flipped my blankets and pillows and looked for it, then I looked between the bed and the wall. It was way back under the bed. I tried to reach for it, yet it was too far down there. I left it, and I went down the hallway and into the kitchen.

Mom usually poured cereal in a bowl for me the night before, and filled a small cup up with milk and put it in the fridge, so that way I didn’t wake her and I could fix breakfast myself. But Mom had forgotten to do it, and instead of trying to dump cereal into a bowl and pour milk from a gallon jug over the food pantry cornflakes, I went straight to the couch and turned the TV on and watched cartoons. The house was cold, and Mom had told me not to touch the thermostat. Frick still hadn’t shown me how to run the woodstove, so I covered up in a blanket and blinked at the television, which was on low, and during commercials I listened for Mom or Frick or Paige to see if they stirred, coughed, flicked their lighters.

After a few shows I heard a door open and the bathroom light flick on and the whir of the fan, and I heard pee hit the water hard, splashing down, and I knew it was Frick. He flushed, came out of the bathroom and into the kitchen and plugged the coffeemaker in. He didn’t say anything; maybe he didn’t see me.