10,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

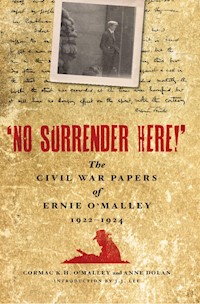

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

JUST OVER a month after the 1921 truce that ended Ireland's fight with England, Ernie O'Malley longed for a return to war. Ten months later he was waging civil war against many of the men he had once fought with, against those who accepted the new Irish Free State. 'No Surrender Here!' The Civil War Papers of Ernie O'Malley 1922-1924 is the first comprehensive collection of letters, memoranda and orders detailing this period of chaos and confusion, intransigence and idealism, which gripped the country from June 1922 to May 1923. These documents detail the war as it was fought with none of the benefit of hindsight and occasional artistry that marks the memoirs of many of the men involved, not least O'Malley's own carefully crafted narratives, On Another Man's Wound and The Singing Flame, published decades later. This collection documents one man's attitude to war and his difficult acceptance of peace, his experience of capture, imprisonment, hunger strike and finally release. In these letters, however, 'No Surrender Here!' also captures the voices of both the leadership and the rank and file: the detached and often inappropriate orders from above, and the confusion of men who, in some cases without boots on their feet, know that theirs is a hopeless cause. Letters to friends and family also reveal the more personal costs of war. These fully annotated documents, given historical perspective with a general introduction by Professor Joe Lee, provide extraordinary insights into the republican mentality during the Irish Civil War, into what remains a contested and controversial period of modern Irish history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Dedicated to Professor John V. Kelleher of Harvard University, who inspired me about Irish history many years ago. Cormac K.H. O’Malley

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Note on the Text

The Background: Anglo-Irish Relations, 1898–1921, J.J. Lee

Personal Setting, Cormac K.H. O’Malley

The Papers in Context, Anne Dolan

Details of Military Service, 1916–1924 and List of Wounds, Ernie O’Malley

List of Documents

Abbreviations

PART I. From the Truce to the Fall of the Four Courts

PART II. Four Courts to Ailesbury Road

PART III. Prison

APPENDICES

I. Text of the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland

II. Draft Programme for Army Convention, 25 March 1922

III. Draft Constitution Adopted at the Army Convention, 9 April 1922

IV. Minutes of the Army Council – Proposals of Free State Delegates

V. Minutes of the IRA Executive Meeting, 16–17 October 1922

VI. Draft Proclamation by the IRA, 28 October 1922

VII. General Orders

VIII. Operation Orders

IX. Routine Orders

X. Memos

XI. Calendars for August 1921–August 1924

XII. Names Mentioned in the Text – Ranks and Positions Held during the Civil War

Glossary of Irish Terms

Bibliography

Index

Plates

Copyright

ILLUSTRATIONS

The following plates are between pages 274 and 275

I

Prison photographs of Ernie O’Malley, December, Hue and Cry, Dublin Castle, 3 June 1921

Note from Ernie O’Malley to Rory O’Connor, Limerick, 10 March 1921, © National Library of Ireland

Agenda for the IRA Convention, 25 March 1922, © O’Malley Papers, UCD Archives Department

IRA Proclamation, 28 June 1922, © O’Malley Papers, UCD Archives Department

Destruction of the Four Courts, 1922, © Eithne O’Brien McKeown, daughter of Denis O’Brien and niece of Paddy O’Brien, both of the Four Courts

Irish Independent report of the end of the occupation of the Four Courts, 1922, © Irish Independent

Ernie O’Malley standing outside the Four Courts, June 1922, © Eithne O’Brien McKeown, daughter of Denis O’Brien and niece of Paddy O’Brien, both of the Four Courts

II

Letter from Liam Lynch to Ernie O’Malley, Fermoy, 25 July 1922, © O’Malley Papers, UCD Archives Department

Letter from Ernie O’Malley to Liam Lynch, 13 September 1922, © Moss Twomey Papers, UCD Archives Department

Irish Independent report of the capture of Ernie O’Malley, 6 November 1922, © Irish Independent

36 Ailesbury Road, Freeman’s Journal, 6 November 1922, © Irish Independent

III

Letter from Marion K. O’Malley to Desmond FitzGerald, Dublin, 22 May 1923, © Desmond & Mabel FitzGerald Papers, UCD Archives Department

Letter from hunger strikers to the Archbishop of Dublin, 17 October 1923, © O’Malley Papers, UCD Archives Department

Ernie O’Malley hunger-strike posters, © O’Malley Papers, UCD Archives Department

Ernie O’Malley, 1926, © Estate of Aodghain O’Rahilly

Acknowledgments

First of all it must be recognized that this publication could not have become a reality without the scholarly diligence, fortitude and thoroughness of Anne Dolan to whom I am deeply indebted. Particular thanks are due to University College Dublin Archives where the Ernie O’Malley Papers and Notebooks (UCDA P17a/b) are located, along with so many other collections. Seamus Helferty, UCDA Director, and his staff, have been more than helpful throughout these several years of research. Over 60 per cent of the documents come from O’Malley resources and most of them are from the UCD Archives. Other institutions and their staffs have also been most helpful, including the Military Archives (Comdt. Victor Laing), the National Archives of Ireland, the National Library of Ireland Documents Department (Noel Kissane, Gerry Lyne and Peter Kenny), Trinity College Library and the Imperial War Museum, London.

Many individuals have been helpful to me over the years in collecting these materials or in giving them their proper context, and I would like to thank Mary Bryan, Dr Marion Casey, Madge Clifford Comer, Dr Jack Comer, Rena Dardis, Dr Richard English, Mrs Brigid FitzSimon, Sigle Humphreys O’Donoghue, Dr Michael Kennedy, Professor J.J. Lee, Dr Deirdre McMahon, Ita (Mrs Paddy) Malley, Martin J. Murphy and Dr Eileen Reilly.

Children and grandchildren of father’s comrades and friends have been most supportive and interested in the preparation of these materials and they include members of the families of Frank Aiken, C.S. (Todd) Andrews, Erskine and Molly Childers, and Eamon de Valera. Other individuals include Austin Barret, Una Barrett, Diarmuid Comer, Garret FitzGerald, Patricia Gallivan, Michael Hayes, Declan Hayes, Paddy Kilroy, Mary Raleigh Kotsonouris, Cronie Magan, Machan Magan, Ruan Magan, Mary Maquire McMonagle, Risteárd Mulcahy, Seán Mulcahy, Ulick O’Connor, Joan Manahan O’Neill, Iseult O’Rahilly Broglio and Roisín O’Rahilly DePasquale.

A special acknowledgment must be given to those people who helped preserve the Ernie O’Malley Papers before they reached the secure environment of UCDA, and these include Frances-Mary Blake, Desmond Greaves, Patrick and Ita Malley, and Marie O’Byrne (Dublin City Librarian). The work of Frances-Mary Blake in voluntarily organizing the extensive papers was essential to their preservation.

A group of people have been helpful in the awesome task of initial transcription of these documents and they include Frances-Mary Blake, Mavis Chase, Mary Cosgrove, Anne Dolan, Deirdre McMahon, Bergin O’Malley, Conor O’Malley and Liam Webb.

Cormac K.H. O’Malley May 2007

The process of deciphering Ernie O’Malley’s handwriting and editing these documents was only made possible by a number of people. Michael Kennedy, Michael MacEvilly, Deirdre McMahon, Peter Rigney and Daithí Ó Corráin clarified a number of issues, not least the finer points of railway companies, IRA commands and Irish surnames. The Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences must be acknowledged for their support, and so too the Centre for Contemporary Irish History at Trinity College Dublin, which generously housed the project. Special thanks are due to Podge and Pauline Dolan, Gillian O’Brien, Mícheál Ó Fathartaigh, Eunan O’Halpin, and Niamh Puirséil, and Joseph Clarke for putting up with Ernie and I for the last few years. My thanks must also go to Cormac O’Malley for introducing me to this project.

Anne Dolan Centre for Contemporary Irish History, Trinity College Dublin May 2007

Note on the Text

The documents are arranged in chronological order. The chronology is taken from the date on which the sender wrote the document, not the date on which it was received. The only exception to this is in the case of descriptive documents written months or years after the event. Such documents are included at the time of the event described. When documents were undated they are included at the most accurate possible point.

The documents themselves have been transcribed as faithfully as possible, or at least as faithfully as Ernie O’Malley’s handwriting would allow. If words are missing, they are missing from the original. Occasionally the missing word is quite obvious and is inserted in square brackets. Indeed, square brackets denote all forms of addition or interference throughout the text. Spelling mistakes have been silently corrected, however capitalization and contemporary spellings remain unchanged. The spelling of names has also been left unchanged and the more popular alternative or the correct spelling indicated in a footnote. Punctuation is largely unaltered and was changed only to make sense of the text. Dates have also been spelled out to avoid confusion. Any form of emphasis is from the original documents.

The abbreviations have been left untouched and expanded only for the sake of clarity or sense. Abbreviations are otherwise explained in the expansive list of abbreviations at the start of the collection. Where abbreviations are duplicated, the correct one, if not obvious from the context, is spelled out in square brackets in the text.

Marginal notes or contemporary corrections or amendments, have, where decipherable, been included and denoted as such. Where the sender has signed a document this is indicated by the word ‘signed’ in square brackets. If the original document was handwritten rather than typed, ‘signed’ is naturally omitted. Material which has been omitted from documents is indicated by ‘matter omitted’, again in square brackets. Such material has been omitted because it was either reproduced elsewhere or because it was of limited meaning without access to all of the letters in a particular chain of correspondence. With some of the more obscure figures, such complete collections of letters are not possible to find. ‘Not printed’ refers to material referred to in the documents which has not been included in this collection either because of the constraints of space, because it could not be found or because it has been published elsewhere. When a document refers to another document within the collection this is denoted in an endnote, which indicates where to find the pertinent document in this collection.

Each document is preceded by its number within the collection; its archival reference number; the name and most senior rank of the sender and recipient at the time of despatch; the address, where known, of the sender; the date of despatch and the internal document reference number. At this point it is also indicated if the document is a copy. When the sender or recipient is in prison their rank is no longer given. Where at all possible the sender and the recipient have been identified. In some cases this has not been possible and has been explained accordingly. Similarly, names mentioned throughout the documents have been, for the most part, identified and explained in endnotes. Often documents refer to individuals by their rank rather than by their names. Where this is the case the names have been added in the endnotes. Given the pace of change within the IRA ranks throughout the Civil War there is occasionally some difficulty in establishing who held which rank, or indeed ranks, at any given time. This is further complicated by the fact that people held more than one position and by certain documents making no distinction between GHQ and Command staff. Where there is uncertainty about the holder of any particular rank this is indicated in an endnote and, where possible, an alternative is included.

The Background: Anglo-Irish Relations, 1898–1921

J. J. LEE

Ireland did not seem a likely field for rebellion at the end of the nineteenth century. True, 1898, the year after Ernie O’Malley’s birth, brought the centenary commemoration of the 1798 rebellion, which stirred the embers of the rebel tradition. But it didn’t seem to bear any relation to the present. The British were by this stage normally stationing between 25,000 and 30,000 troops in Ireland, and maintaining about 10,000 police, the Royal Irish Constabulary, as an armed force, in contrast to the unarmed police of Britain. In the improbable event of these forces proving insufficient to crush revolt, reinforcements could be rushed across the Irish Sea. The logistics of physical force were indisputable. It was inconceivable that any Irish rebellion could succeed against overwhelming British force. The three rebellions of the nineteenth century, those of Robert Emmet in 1803, of Young Ireland in 1848, and of the Fenians in 1867, had been such hopeless military failures that even the most ardent Irish rebels were forced to recognize the reality of Britain’s overwhelming command of physical force. The celebrated phrase, ‘England’s danger is Ireland’s opportunity’, accepted the premise that unless England were engaged in conflict with an enemy of comparable power, a rising against the British army in Ireland would have no chance of success (in this essay Britain and England are used interchangeably, in accordance with general contemporary usage, however imprecise, in England and Ireland).

The biggest Irish political organization, the Nationalist party, simply assumed this as a fundamental reality. Although holding about 80 per cent of Irish seats, it believed that a campaign for a sovereign Irish state stood no chance whatsoever against superior British gun-power, and contented itself with demanding ‘Home Rule’. Under John Redmond’s leadership since 1900, success appeared to have been at last achieved, when the Liberal government of H.H. Asquith introduced the third Home Rule Bill in 1912. It was not to be, though anybody predicting the events of the next decade could have been deemed crazy, so improbable would they have appeared – although one should also recognize that even had Home Rule been enacted the consequences were also highly unpredictable.1

The denouement is well known. There is little dispute about the facts, but huge divergence on interpretation. In short, Irish unionists in general, mainly the 25-per-cent Protestant sector of the population, largely descended from the seventeenth-century English and Scottish conquerors, planters, and settlers, rejected the idea of Home Rule. Their reasons included their fear of persecution by the 75-per-cent Catholic population, their contempt for the capacity of axiomatically inferior Catholics to rule effectively, with rapid economic ruin the inescapable consequence, and their satisfaction with the material and emotional rewards of their status among the ruling races of the British Empire.

This unionist resistance in Ireland attracted the powerful support of the Conservative and Unionist party in Britain. Indeed ‘Unionist’ had been added to the title in the context of its successful campaign against Gladstone’s first Home Rule Bill in 1886, to more formally confirm its ideological support for the Union. Gladstone’s second Home Rule Bill actually passed the House of Commons, but was decisively defeated by the Conservative and Unionist majority in the House of Lords in 1893. However, once the Parliament Act of 1911 curbed the power of the Lords to veto Commons legislation for more than three sessions, Irish unionism had lost its hitherto impregnable shield. The rhetoric of unionist resistance suddenly changed. Rebellion, long denounced as a character deficiency in the Catholic Irish, was now extolled as the last refuge of free-born Britons about to be deprived of their birthright and delivered into the unworthy hands of their ancestral enemies, sodden with the innocent blood of the Protestant victims of the Catholic propensity for atrocity, most notoriously in 1641.

Conservative support for unionism was natural. It was the Unionist party after all. What was new was the unconditional support of the party leader, Andrew Bonar Law, for violent resistance to a parliamentary decision in favour of Home Rule.

Bonar Law, the New-Brunswick-born son of a formidable father from Coleraine, a Presbyterian minister of imposing personality, blending a sense of Old-Testament righteousness with an increasingly brooding disposition,2 promised to support the resistance of Ulster unionists to Home Rule to whatever lengths they chose to go in rhetoric invoking the spectre of civil war not only for Ireland but even for Britain itself. Opinions differ as to how far this was a tactical ploy in the ceaseless power-game of British party politics, with Ireland, and even Ulster unionists, simply pawns in the Westminster game, or how far he was prepared to plunge Britain into civil war to crush Home Rule and presumably seize power for the Conservatives, relying on the support of the army in the crusade to preserve the United Kingdom. Given that the officer class was overwhelmingly of Conservative vintage, Bonar Law’s threat could appear no empty one, even if it was a bluff. The risk involved in calling the bluff, if bluff it were, was bound to make even a less sensitive soul than Asquith recoil from the possible implications.

This raises fascinating vistas – appalling or attractive depending on one’s perspective – of the ‘virtual history’ of Britain. Among the possible ‘virtual’ histories that can be imagined, the most intriguing of all is what might have happened if circumstances obliged, or enabled, Bonar Law to proceed with his threat? Was this one of the great potential turning points at which British history was spared from turning, which might have required all that great history to be reinterpreted as a prelude to another civil war, no longer broadening sonorously down the Whig highway from precedent to precedent?

It was not that Home Rule, as actually proposed in Asquith’s bill of 1912, involved the establishment of a sovereign Irish state. Home Rule was not sovereignty.3 In fact a Home Rule government would have little more than local government powers, in some respects less than those of an American state. It could have no foreign or defence policies, prerequisites for sovereignty. The British army would remain in the country, and there could be no Irish army. It had only limited power over taxation, and none over such major contemporary issues as land legislation, old age pensions, and national insurance. It could pass no legislation affecting religion, or the role of the Churches in education. A Home Rule parliament would operate in a straitjacket imposed by the British. Home Rule, in short, was what was left over for Ireland after Britain had decided what to retain. One can therefore understand why as perceptive and judicious an authority as Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh could observe that Home Rule was largely symbolic.4 But it was a symbol around which nearly every Irish nationalist could rally, if with widely varying degrees of enthusiasm. Home Rule was such a very broad church that as anaemic a proposal as Asquith’s could be welcomed even by Patrick Pearse, four years later the leader of the 1916 Easter Rising – if in his case coupled with the warning that if Britain reneged on her proposal this time, the result would be war.

Even as Pearse spoke in April 1912, it was already becoming clear that Britain might fail to follow through the proposals contained in Asquith’s bill. The formidable unionist leadership of the Dubliner, Sir Edward Carson, an accomplished parliamentary and public performer, his chief lieutenant, Sir James Craig, a craggy Co. Down Presbyterian whiskey distiller, and Bonar Law, found Home Rule deeply offensive in itself. They found it even more offensive in that they saw it as merely the thin edge of the sovereignty wedge. Outraged at the thought of being in any respect subject to the mere majority rule of their hereditary inferiors, and consumed with fear that Home Rule was only the prelude to a drive for sovereignty, they scoffed at Asquith’s portrayal of Home Rule as ensuring permanent acceptance by Irish nationalists of the legitimacy of British sovereignty in Ireland, a form of killing Irish nationalism by enveloping it in the ample folds of British imperialism ruling over lesser breeds. No legislative guarantees that the authority of the United Kingdom Parliament remained supreme over the Home Rule Parliament could mollify them. They therefore determined on a pre-emptive strike against the feared potential of a New Home Rule Order, giving a sense of direction and discipline to the widespread determination of grassroots Ulster unionists to resist Home Rule by as much violence as necessary. Ulster unionists grasped the fundamental reality of the gun from the outset. If they could face down parliament by the ‘moral force’ of constitutional tactics, well and good. If not, they would mobilize all possible ‘physical force’ in defence of their birthright.

This popular unionist instinct was arguably quite sound. However vigorously ideologues on one side or the other of the constitutional/insurrectionary divide in Irish nationalist politics strove to suggest an unbridgeable gulf between them, activists in both camps were revered in the popular Irish mind for having done their best to achieve as much Irish self-government as possible, however different their means. The young Ernie O’Malley himself would observe, with the bemusement of the doctrinaire, how portraits of the constitutionalist Daniel O’Connell and the rebel Robert Emmet, juxtaposed as irreconcilable polar opposites by ideologues like himself at the time, often complemented one another in the homes of the people during the War of Independence.5 In reality, as an historian with a profound understanding of public opinion has observed, ‘In the popular perception … Home Rule transcended specific legal and political categories and denoted, quite simply, Irish control and Irish power. Home Rule was freely interpreted as the ending of the Union, the undoing of the conquest and the panacea for Irish problems.’6 As Alan Ward in turn crisply comments, ‘The problem for Liberal politicians was that unionists chose to interpret home rule in exactly this way, and it terrified them.’7

Ulster unionists played a resolute and effective hand for themselves at this stage, above all because they realized that the more it was stacked with guns the stronger it would be. They concurred entirely with the sentiment expressed by Patrick Pearse, commenting caustically in November 1913 on the arming of the UVF that he thought ‘the Orangeman with a rifle a much less ridiculous figure than the Nationalist without a rifle’.8

Ulster unionists believed their only guarantee was the gun. Parliament might propose, but the gun would dispose. The outcome of their threat of rebellion was the recruitment of an Ulster Volunteer Force of about 100,000 men during 1913, increasingly armed, especially after a brilliantly orchestrated gun-running exploit at Larne in April 1914 brought 25,000 rifles and 3,000,000 rounds of ammunition ashore. Though many of the weapons were of poor calibre, and ammunition was scarce,9 this nevertheless left them far better armed than the Irish Volunteers, who were established, in response to the UVF, in November 1913, to support Home Rule. Their most ambitious effort managed to bring in only roughly 1400 guns in July, leaving the UVF the best equipped force by far in the country except for the British army.

Had the army moved decisively against the UVF it could still have crushed it at this stage.10 But this had ceased to matter once senior British officers at the Curragh Headquarters in Ireland intimated in March 1914 they would resign rather than obey government orders to compel Ulster unionists to recognize a Home Rule parliament. This made it clear that the Ulster unionist cause enjoyed widespread sympathy in the British officer class, now providing redoubtable if indirect support for Bonar Law’s position, who in turn could take encouragement from the way the military wind was blowing. As the notable biography of Bonar Law by Robert Blake explains:

Bonar Law’s conduct cannot be understood unless it is remembered that he was himself an Ulsterman, and deeply felt the character of a measure which would put his fellow countrymen under the rule of their hereditary enemies in Southern Ireland. He really believed that a Dublin parliament would ruin Belfast, that the liberties of the Ulsterman would vanish, that a prosperous enlightened community would be subjected to intolerable treatment at the hands of Southern bigots, that it was an outrage to drive out from their allegiance to the Crown a population which was so clearly determined to remain loyal … .

In this image, ‘Ulsterman’ by definition meant unionists in Ulster, in accordance with standard unionist nomenclature, ‘Ulster’ in rhetoric being an idea blissfully cleansed of Irish nationalists. Robert Blake himself, one of the outstanding English historians of his generation, further comments:

Ireland was – and is – a land of bitter, irreconcilable, racial and religious conflicts. The Protestant minority could never hope by any swing of the political pendulum to become the majority. The two nations in Ireland were separated by the whole of their past history. They were divided by rivers of blood and bitterness. It was absurd to believe that the conventions which prevailed in placid England would be accepted by the Ulster Protestants with all this fear, suspicion and hatred in their hearts … Bonar Law at an early stage saw that the problem of Ulster was a genuine problem of frontier nationalism. As he repeatedly declared, it was ultimately a question of civil war. In a civil war you cannot expect from the armed forces that unquestioned political neutrality which is found in normal conditions.11

Resistance through resort to violence was a natural corollary of this cast of mind. It has indeed frequently been claimed that the arming of the Ulster Volunteer Force first brought the gun into Irish politics in the twentieth century. But it did not. All Irish politics under the Union took place in the permanent shadow of the gunman – the British gunman. The arming of the UVF in 1913–14 abruptly altered this situation but it did not bring the gun into Irish politics. The gun was already there, as the fundamental fact of political power, the bedrock on which British domination was based. That it can be conjured out of existence is either wishful thinking or testimony to the hallucinogenic impact of British mind games. The power of domination derives even more from capturing the minds than the bodies of the dominated – whether in terms of nationality, race, ethnicity, religion, class, gender, age or any other marker of identity. Part of the genius of British domination skills in Ireland was to so skilfully disguise the elementary fact that British gun-power determined the framework within which Irish politics operated. The suffocating skill of British control techniques had ensured that for many, British guns in Ireland were somehow purged of any association with violence. Conquest was not violence. It was only resistance to conquest that was violence. The clue to British success in this respect was to have such superiority in guns that they did not have to be used. Even otherwise independent minds could be induced to persuade themselves they really didn’t exist at all, or were purely ornamental, and that the only purveyors of violence were those who were misguided and unmannerly enough to seek to resist so overwhelming a command of violence.

That this fundamental fact of power relations could be so long obfuscated is the finest tribute that can be paid to British governing skills. This of course is to fly in the face of much conventional wisdom, that the stereotypically imaginative Celts were masters of propaganda compared with the stereotypically stolid Saxons. The truth, however, is that crass though individual bits and pieces of British propaganda might have been, they occurred within a framework of psychological domination, that deserves clear recognition of the manner in which it came to influence, and often capture, so many Irish minds, not only through repression, but through seduction too, including arguably those of Ernie O’Malley’s parents and brothers.12

What the UVF did was to bring in a second gun in a manner sufficiently serious to expose the existing order. That meant that the UVF gun now became the potentially dominant over whatever territory the ultimate controllers of gun-power, the British army, decided to permit. The UVF could not defeat the British army if the British choose to mobilize their own full potential physical force. It was the Curragh Mutiny that decided they wouldn’t, and therefore in effect determined that the UVF gun would be not merely the second, but the first, gun over whatever area it chose to control.

This was the context in which John Redmond, the Home Rule leader, urged his followers to join the British army after Britain declared war on Germany in August 1914. Often though he has been criticized for this it is difficult to see how Redmond could have acted otherwise in the circumstances. Even if his personal inclination tended strongly in that direction, the gun situation in Ireland left him little choice. His hand was incomparably weaker than that of the government, or the UVF, simply because there were so few guns in it. Home Rule did indeed go on the statute book in September, but with its operation immediately suspended until after the war – and with the proviso that the Ulster problem remained to be resolved, leaving partition therefore, along whatever border, a likely outcome.

Redmond believed passionately in a united Ireland. He abominated the idea of partition. But he realized that not only the British army, but the UVF, had far more guns than his supporters.13 Therefore at the end of the war – and most expected it to be over within a year – he had to assume that he could not, even if he wished, force Ulster unionists, who would now be even more formidable thanks to better training and improved equipment acquired through military service, into a Home Rule Ireland – or prevent them forcing as many Irish nationalists as they wished into their ‘Ulster’. He knew too that the British army would not thwart Unionist policy. Opinions may differ as to the realism of Redmond’s aspirations towards killing unionism with promises of kindness, but given the gun situation, and the British refusal to allow him raise explicitly Home Rule divisions – precisely for fear of how he might use them at the end of the war – in contrast to allowing Carson raise anti-Home Rule forces, he had no realistic alternative but to support British war policy by urging his supporters to join the army. As it was only through negotiation that the partition he detested could be avoided, he had to appeal to a union of hearts, out of calculation as well as conviction.

We cannot know what would have happened but for the war. It is another instructive exercise in ‘virtual history’ to imagine Ireland’s history (or for that matter Britain’s) had Britain not chosen to declare war on Germany – and had the war not lasted so long. Would the failure to achieve agreement on partition at the Buckingham Palace Conference in July 1914 have indeed led to civil war within the United Kingdom, or would the rivals have refrained from plunging Ireland and Britain into internal conflict in the light of the uncertainties on the continent? What would the implications of internal conflict have been? There would presumably have been no Easter Rising, predicated as it was on the arrival of German guns, with all the consequences of this for the fortunes of Redmond’s party – unless the course of the war worked itself out differently had Britain remained neutral in the first instance, or even if it had entered later. But conflict in Ireland would also have had major consequences for Redmond’s party. Who would the military leaders have been? Would Redmond, no natural war leader, have been sidelined, as Asquith would come to be in England? But by whom? Would Ulster unionists, much better armed than Irish nationalists, and with the implicit or explicit support of the British army, have imposed their own terms?

Would British troops have been withdrawn in order to crush foolhardy Home Rule supporters in England? Why would they have had to be withdrawn if the army in Britain itself remained united, and all their guns were on the unionist side? Would British politicians, even Bonar Law, have been reduced to the level of Irish nationalist politicians against the irresistible power of the gun? Would Kitchener, or a like-minded colleague, have become a military dictator, an English Ludendorff behind a figurehead civilian? And assuming an army/Tory victory, why give any Home Rule to the Irish instead of teaching the natives their proper place – or if really clever, instituting a regime of collaborators by conviction as well as collaborators by calculation. Or would the renowned British capacity for finding formulae conducive to constitutional compromise emerge triumphant once more? The possibilities are legion, and one is tempted to wax wistful over how interesting Anglo-Irish relations might have become but for the untimely intervention of the First World War. But perhaps it is better that we have been spared the knowledge.

Despite Redmond’s pleas, recruitment remained lower in Ireland than in Britain, and lower among Catholics than Protestants. Some of the volunteering among Catholics may have been driven by a genuine belief, deluded again by the hallucinatory effects of war propaganda, that as Britain claimed to be fighting in defence of small nations, this would ensure the implementation of the Home Rule Act. Among Protestant recruits, many drawn from the UVF, the intention was the precise opposite. Redmond’s romantic rhetoric, that service together (even for the short, anticipated war) would foster a bond of brotherhood between Irish unionist and Irish nationalist, was forlorn from the outset. Even if it did foster fraternity, it is not clear why the unionists should feel seduced by the potential delights of Home Rule rather than the Irish nationalists by the potential delights of empire.

There had probably never been so many guns in Irish hands as during the First World War. Ironically it was the hands with the smallest number of guns in them, those of the Easter rebels of 1916, that would have the biggest impact on Irish history. It has of course been usual to attribute a dramatic and unforeseeable transformation in public sentiment to the Easter Rising. It now appears that opinion may have been growing disenchanted with the sour fruits of Redmond’s policy of unconditional support for Britain, to the extent that a degree of emotional withdrawal was already under way among even substantial numbers of Redmond’s supporters, and even if no practical alternative appeared to recommend itself.

When that withdrawal began can be debated. John Dillon, Redmond’s closest lieutenant, felt in retrospect that it began with the admission of Sir Edward Carson to the Cabinet in 1915. Redmond was invited to join at the same time, but felt obliged to refuse. Dillon commented in September 1916 that ‘the fact is that ever since the formation of the coalition in June 1915 we had been steadily and rather rapidly losing our hold on the people, and the rebellion and the negotiations only brought out in an aggravated form what had been beneath the surface for a year’.

Whatever the precise modalities, Redmond’s grip was clearly loosening before the Rising, even if he was still the leader of nationalist Ireland. The big majority of the Irish Volunteers had indeed followed him into the new National Volunteers, formed after the leadership of the original Irish Volunteers rejected his appeal to fight for England in September 1914. Only a small proportion of Redmond’s followers, however, less than 20 per cent, actually joined the army at the time.14 Although membership remained far higher than that of the Irish Volunteers, enthusiasm drained away, total membership – and that becoming increasingly inactive – falling from 184,000 to 107,000 between August 1914 and February 1916.15

The dissidents, led by Eoin MacNeill, who retained the original title of the Irish Volunteers, had a quite disproportionate share of the energy and intellect of the organization. It was among the Irish Republican Brotherhood members among them, including Tom Clarke, Seán MacDermott, and Patrick Pearse, that the plan for a rising on Easter Sunday 1916 gradually germinated. The IRB, long somnolent, had acquired more purposeful life once the old Fenian, Tom Clarke, returned from America in 1907, and began revitalizing the IRB with a view to a rising.

The eventual Rising of Easter Monday 1916 was not, however, the action they had planned for Easter Sunday. The day’s delay revolved once more around guns. The 20,000 German guns the rebels expected to have been landed in Kerry on Easter weekend had been intercepted by the British navy. Of an antiquated Russian type, they might not in the event have made much difference. But that had not been the plan. The request to the Germans was for at least 20,000 of the most modern type of rifle, 5,000,000 rounds of ammunition and ten machine guns.16 Even then a rising might have been crushed quickly, for much of the planning for the use of the guns throughout the country seems to have been rudimentary. Nevertheless, once guns were available one cannot predict what dynamics might have come into play. Certainly it would not have been the same rising as actually occurred.

That rising was indeed a blood sacrifice, as it has been traditionally depicted, given that it had no possible chance of success. Yet however much this may have satisfied a deep inner yearning for martyrdom on the part of some of the leaders, that was not the original plan. The aspiration was for serious insurrection, not for symbolic gesture. The Rising of Easter Monday was not the Rising planned for Easter Sunday postponed by a day. It was a different Rising.

Once again, there can be many readings of the ‘virtual’ Irish history that might have been if the Easter Rising had occurred according to plan. Ironically it was less guns than the lack of guns, that caused it to come to be engraved on minds not only in Ireland, but beyond. The suppression of the Rising, and the subsequent execution of the leaders, snapped many out of the trance-like assumption that the gun was no part of the British control system in Ireland. Once the British were obliged to exhibit their superior command of violence, the hollowness of the assumptions behind their constitutional rhetoric began to be exposed.

Whether the Rising was a watershed, or instead accelerated tendencies already emerging, can be debated. There were many different paths leading to the Rising, leading through the Rising, and leading from the Rising. Even where it may have accelerated rather than created, however, it did so in a way that cast the working-out of those tendencies in an unforeseeable mould, as in O’Malley’s own case, bringing to the fore names unknown before the Rising, pre-eminently Eamon de Valera and Michael Collins. The immediate institutional beneficiary of these developments, however, was an established organization, Sinn Féin.

Founded by Arthur Griffith in 1905, Sinn Féin strove to inculcate a greater sense of independence of mind into the public. Sinn Féin meant ‘Ourselves’. It would often be translated as ‘Ourselves Alone’. But this was mainly a ploy by the malignant or ignorant, or both. Desperate to discredit the Sinn Féin philosophy of self-reliance as one of insular obscurantism, axiomatically inferior to their own allegedly cosmopolitan perspectives, they struck on the tactic of dismissing it disdainfully as one of ‘narrow nationalism’. There were ‘narrow nationalists’ in Sinn Féin, though even their minds may have been less derivative than many among their critics, confusing their own variety of narrowness with cosmopolitanism. But the post-Rising Sinn Féin was not the Sinn Féin of Arthur Griffith. The name ‘Sinn Féin Rising’ stuck to the Easter Rising despite the fact that Sinn Féin as a party was not involved in it. But the British dubbed it the Sinn Féin Rising, giving the party an enormous post-Rising boost as public opinion came to align itself with the rebels.

If the name persisted, however, the party was in effect hi-jacked by the survivors of the Rising. In October 1917 the presidency was taken over by Eamon de Valera, the senior surviving officer of the Rising, Arthur Griffith being relegated to vice-president of his own organization. But he could hardly complain. It was in effect a new movement. Gifted and tireless a propagandist though Griffith was, he could not have hoped to have turned his Sinn Féin into the vote-getting party it would now become.

The relative standing of the Home Rule party and of Sinn Féin changed significantly after the Rising. The drift to Sinn Féin was reinforced by the duplicity of David Lloyd George, the government minister delegated by Asquith in May 1916 to try to implement the Home Rule Act rapidly to prevent Ireland sliding into resistance. Lloyd George, arguably the most consummate British politician of the century, gave a virtuoso performance in persuading Redmond to accept partition on a six-county basis in exchange for immediate Home Rule. Unfortunately for Redmond, it emerged by July that while he had agreed to partition as a temporary arrangement for six years, Lloyd George had promised Sir Edward Carson – in writing, for Carson knew his man – partition in perpetuity, thus giving ammunition to critics of Redmond’s gullibility in accepting fraudulent assurances from the feline lips of the most slippery, if gifted, operator in British public life.

The shift of public opinion towards Sinn Féin, reflected spectacularly in the by-election victory of Eamon de Valera in Clare in July 1917, was reinforced by the British threat to impose conscription on Ireland in March 1918, the same month, ironically and poignantly, that Redmond died, his once-great party already imploding. Sinn Féin success in winning 73 of the 105 Irish seats in the general election of December 1918 was remarkable, despite frantic retrospective propagandistic attempts to denigrate it. But it is important to remember what the victory represented. Sinn Féin liked to present it as a dramatic shift from the fatalistic caution of a Home Rule vote for a glorified form of local government to the exuberant embrace of a sovereign republic. And for some, it was that – particularly young men (and young women too, except that while women over thirty got the vote for the first time, women under thirty still did not). But given that for most Irish people Home Rule simply meant as much independence as possible, what has to be explained is how Sinn Féin was able to project a new concept of ‘the possible’.

As 1916 had been a military failure, however spectacular a propaganda success, it would have been singularly insensitive of Sinn Féin to have campaigned on the basis of an immediate resumption of rebellion. Sinn Féin could not have campaigned in any case on the basis of an instant renewal of the fight, if only because even its most militant supporters had precious few guns at this stage. But this did not stop Sinn Féin from wrapping itself in the rebel flag, and campaigning on a Republican platform, while intimating that no further rebellion, however justified, would be necessary. Sinn Féin purported to have discovered the secret of taking the British gun out of Irish politics. How? Firstly by setting up an Irish parliament in Dublin. This it duly did in convening Dáil Éireann on 21 January 1919. Refusing to recognize the legitimacy of British rule in Ireland, the Dáil immediately proclaimed an Irish Republic in direct descent from Easter Week.

Secondly, as the thought did happen to cross its mind that the British might not be receptive to this change of venue for decision-making about Ireland, the second string to the Sinn Féin bow was to circumvent Westminster by appealing to the Peace Conference being convened in Paris to determine the New World Order that President Wilson had proclaimed on the basis of his Fourteen points, basic to which was the right to national self-determination. Sinn Féin’s tactic was to take the British gun out of Irish politics by appealing to the higher principles that would allegedly govern the proceedings of the Peace Conference. A change of the decision-making arena would at a stroke change the centuries-old role of the British gun in Irish history. Changing the forum of decision-making would allegedly change the decisions themselves.

It sounded fine in theory. But it was too clever by half. Taking the gun out of Irish politics was the one thing the British government could not concede. It would have been deprived at a stroke of the basis of its power in Ireland. In practice, it required a suspension of disbelief that a conference of the victors would apply their own principles to themselves. The Sinn Féin delegation was duly refused entry to the Peace Conference, and the attempt to present Ireland’s case failed utterly, as was entirely predictable.

If the Peace Conference tactic never stood a chance, Sinn Féin took, or purported to take, Wilsonian rhetoric about self-determination, making the world safe for democracy etc. at face value, and to invoke it for its ends. Sinn Féin trust in the American card, if not in Wilson’s playing it, did not end there. It was in pursuit of the will-o’-the-wisp of American recognition of the Irish Republic that de Valera, as president of the Republic proclaimed by Dáil Éireann, would spend eighteen months in America from June 1919 to December 1920, to try to get America to put pressure on Britain to withdraw its guns.17

It was the presence of those guns that determined the parameters within which much of Irish politics would continue to move. John Dillon, Redmond’s closest lieutenant, sensing in 1917 the potential for further revolt, expressed his sense of despair at the futility of the challenge to the dominance of the British gun:

I have never in the whole course of my public life said – and I never will – one word against physical force when it was used in a just cause and with some hope of success, but to hurl the unarmed youth of a nation like Ireland, who have been throughout the whole history of the country signalized by martial courage, what I may describe as reckless courage, to hurl them unarmed up against the infernal machinery that has been devised for the destruction of human life in modern war, is a crime or an act of unspeakable folly.18

The emerging activists among republicans would strongly dispute this style of reasoning. Crime it could not be, for they shared the view simply expressed by O’Malley that ‘no one had a right to Ireland except the Irish’.19 ‘Unspeakable folly’ it would not be in their minds. Dillon’s concern was with ‘unarmed’ youth taking on heavily armed foes. The ambition of the aspiring rebels from 1917 through to 1921 was to make sure they would not be ‘unarmed’. Getting guns was a prerequisite for any hope of matching gun with gun. Physical force could in their minds be undermined only by confronting it head on. The initial stages of the War of Independence revolved inescapably on the Irish side around getting weapons.

As the main way to get guns was to capture them from the armed police force, the Royal Irish Constabulary, the early stages consisted mainly of attacks on police. Had the RIC not been armed, there would probably have been fewer attacks on them then. It would not be until September 1919 that the first British soldiers would be attacked, again ‘for their rifles’.20 It was continuing British superiority in guns that allowed them continue to dominate the country after the 1918 general election, convinced that the bullet was mightier than the ballot. And so it was – as long as the British had the will to use their massive superiority in bullets. The instinct was so ingrained in the Irish nationalist public that resistance was useless, as by any objective reasoning it was, that despite sporadic success in getting guns, O’Malley found it a major challenge to overcome the ingrained fear of defeat, especially among the older generation.

But did the British have the will to apply their full firepower? The IRA campaign presented the British government with a dilemma. The great Tory leader and Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, Gladstone’s formidable adversary on Home Rule, had expressed that dilemma pungently in the celebrated assertion in 1867 that ‘Ireland must be kept at all hazards; by persuasion if possible, if not by force’.21

It was no idle threat. For it is easy to overlook, through the haze of Republican propaganda, the extent to which the British gun continued to reign supreme in Irish affairs during the War of Independence, despite spectacular individual actions by the IRA, into whom the Volunteers had evolved. The badly armed IRA could count many thousand members. But except for former British soldiers among them, they had only rudimentary training, and no more that 3–4000 rifles and handguns between them. The 37,000 British troops they faced in November 1919 gradually increased to 40,000 by March 1921 before rising to no fewer than 60,000 in the summer.22 True, their officers insisted many of them were not ready for combat. But they presumably knew how to fire a gun. And they had guns to fire. That was more than most IRA men had. In addition the Crown forces had been augmented by units of Black and Tans, and of Auxiliaries, specially recruited from First World War veterans with a taste for further fighting, and with a licence to cower the public into a submissive mood. The escalating conflict was also an exercise in basic political education, reinforcing the lesson of 1916 in stripping away the beguiling but self-deluding façade of ‘constitutionalism’, behind which the British gun was disguised. But education in itself could not defeat superior gun-power.

British and Ulster unionist confidence in physical force was by no means as misplaced as the myth that the IRA ‘won the war’ has led many to believe. It was, above all, through the overwhelming force of their arms that a line of partition could be imposed around six of the nine Ulster counties under the Government of Ireland Act in 1920. The ‘Ulster’ question had been central to British policy since the Ulster unionists threatened revolt in 1912. The numbers involved were small. But the principles at stake were central to the concept of democracy. The principle enshrined triumphantly in the Government of Ireland Act was that the hand with the biggest gun in it held the whip hand.

The first proposal from a British MP for partition in 1912 had envisaged a four-county Northern Ireland. The two counties with Irish nationalist majorities, Fermanagh and Tyrone, that would subsequently be incorporated into a six-county Northern Ireland, were envisaged as coming within a 28-county Home Rule territory at that stage. Eight years later the two counties still had Irish nationalist majorities. Their county councils still voted themselves out of the new Northern Ireland established by the British in 1920, and were promptly dissolved by the new Northern Ireland regime. What had changed was not the balance of population, but the balance of gun-power. The rise of the UVF from 1912–13, and the fundamental fact that the government would not use the British army to impose any policy unacceptable to east Ulster unionists, meant that the line of partition would be whatever those unionists chose. And so it came to pass.

There can be any variety of views on the partition question. What there can be no variety of views on is that of the central role of the gun in imposing the decision of the physically stronger forces. Ulster unionists were as convinced of the righteousness of their cause as the most ardent Irish nationalist. But it was not the relative power of belief, but the relative power of the gun, that determined firstly that there would be partition, and secondly where the line of partition would be drawn. The great advantage Ulster unionists had was their unswerving recognition of the central role of the command of violence. The border was determined not by moral force, not by constitutionalism, not by consent, but by the power of the gun in the hands of the special unionist constabularies rapidly and effectively organized after the end of the war, ‘in practice the UVF reconstituted under an official name’.23 The line of the border stood as irrefutable evidence that far from achieving nothing, command of violence was crucial in determining the outcome of the conflict over partition.

It was the unblinking, unwavering recognition of this fundamental reality that explains how those who constantly insisted that Irish nationalists could not ignore the will of the 25-per-cent unionists among the population were themselves able to ignore the existence of the 35-per-cent Irish nationalists within the borders they imposed on Northern Ireland. But it was not their numbers alone that allowed Ulster unionists determine their territory. The minority as a percentage in that territory was not only bigger than the Ulster unionist minority in Ireland, and was in an actual majority over a substantial part of that territory bordering on the line of partition. It didn’t matter because Irish nationalist gun-power vis-à-vis the UVF, even without the British army in support, was so inferior. The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 would duly stipulate that the border should be located ‘according to the wishes of the inhabitants, in so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic circumstances’. In the event it was none of these factors that determined the line of the border after the Treaty any more than before. It was command of violence.

The Irish situation was not, however, nearly as simple as the Sinn Féin electoral victors declared. If by the simple criteria of ‘democracy’ and ‘self-determination’, as applied by the winners to the losers after the First World War, Sinn Féin, like Redmond before it, had a powerful case. The fact remained that it had no more idea than Redmond how to cope with Ulster unionist armed resistance to Home Rule, much less to an Irish state verging on real independence. In principle it could try either to compromise with Ulster unionists, or, if no compromise could be agreed – and why should Ulster unionists compromise on anything, when they had the guns? – to meet gun with gun, except that it hadn’t remotely enough guns to do that.

This is not to say that the outcome may not have worked out better, or at least less destructively, at the time than any likely alternative arrangement. For if the IRA had been stronger, who knows how much bloodshed would have been spilt, or horrors ensued, in what could have involved the worst aspects of a race war, if both the UVF and the IRA were determined to fight to a finish. The ‘virtual history’ of Ireland, benign or malign according to taste, had the IRA been as well equipped as the Ulster unionist forces, can be debated interminably, depending on one’s values and assumptions. What cannot be debated is that gun-power, and calculations about gun-power, were crucial in determining the ultimate outcome.

It is part of the indulgent self-image of Irish nationalism that Northern Ireland was what was left over after the Irish Free State was established. Hence one regularly endures the almost axiomatic regurgitation of the myth that the Treaty of 1921 created partition. It was in fact the other way round. The Irish state was what was left over after the British government had imposed the particular six-county border at Ulster unionist behest. Then, and only then, would the British government turn towards an agreement with the troublesome, leftover twenty-six counties. Once the Northern Ireland parliament had been opened in June 1921, the government duly went into disengagement mode, agreeing a truce with Sinn Féin from 11 July.

It is easy to overlook the significance of the British decision for a truce. It would soon be overshadowed by the Treaty and Civil War. But it was the first time in modern Irish history that the British had agreed to an open-ended truce, if only after achieving a crucial objective, a settlement satisfactory to Ulster unionists. But there would be plenty of kicks left in the tail of the British gun yet. It remained discreetly concealed during the Treaty negotiations that began on 11 October until British patience snapped on 5 December 1921. Lloyd George, now Prime Minister and leader of the British negotiation team, decided to bring the Irish delegates back to the world of reality. It had been easy for the delegates to deceive themselves they were negotiating as equals in the atmosphere of apparent ‘let us all be friends together’ around a table in Downing Street, as the British delegation sought to seduce the Irish into the belief that they were all reasonable people. When the Irish actually began to behave as if they were equals, and seemed to believe the issue revolved around the quality of the argument, as distinct from the realities of gun-power, Lloyd George decided it was time to inject a dose of reality by threatening ‘immediate and terrible war’ if the Irish did not agree to the British terms. This was no academic seminar, consumed with the search for truth. Physical force would decide. It was a reality check for the Irish delegates – as for any account of Irish history with the British gun left out.

That threat was decisive in bringing the Irish delegation to heel. The calculation of the balance of gun-power played a crucial part in the decision of Michael Collins, and subsequently several members of the General Headquarters Staff of the IRA, to support the Treaty. It may be that at the back of Collins’s mind this was still only war by other means, as O’Malley’s account suggests24 – although Collins played so many games that one can never be certain what his real game was at any given time, or which game was long-term, and which merely tactical under the pressure of short-term forces.25 Collins, a dynamic blend of romantic imagination and singularly unromantic application, had been clear a year earlier that ‘it is too much to expect that Irish physical force could combat successfully English physical force for any length of time if the directors of the latter could get a free hand for ruthlessness’.26

Collins was indisputably right that had the British government chosen to apply its full potential gun-power against the IRA, there could have been only one outcome. So why did the British physical force element not ‘get a free hand for ruthlessness’?

It was more complex than that for Lloyd George. There was a financial factor to be considered, as British public finances had been badly damaged by the World War. There was some social unrest in Britain itself. Moreover, demobilization had sharply reduced the size of the army, which was also stretched imposing order on other natives throughout the empire. Lloyd George, too, as the supreme negotiator of his age, could feel confident of out-manoeuvring the Irish at the negotiating table, as he had out-manoeuvred so many others at national and international level. True, he would have preferred to have crushed the IRA, and had earlier encouraged Hugh Tudor, commander of the Auxiliaries, to get on with the pacification work, while he delicately averted his gaze.27 He now found himself, on 5 December, reduced to the crudest of threats – terror. Had his ultimatum failed, it would have been a confession of tactical bankruptcy. But it did not fail. The historian – leaving aside entirely personal preferences – might wish it had, for the subsequent ‘virtual histories’ one can envisage would tell us so much more than we can ever know about the personalities involved on all sides.

The capitulation of the Irish delegation meant that Lloyd George didn’t in the event have to face that question of what were the limits of the ‘force’ to which Lord Salisbury had referred if ‘persuasion’ failed, that Britain would deploy to hold Ireland ‘at all costs’? Was he, for instance, going to give ‘a free hand for ruthlessness’ under the rubric of ‘terrible war’? What level of terror did he, and perhaps even more his mainly Tory cabinet, contemplate this ‘terrible war’ descending, or ascending, to? Would more use have been made of airpower, as Sir Henry Wilson wanted?28 Would guns in the air now be given free rein to aid the guns on the ground in instructing the natives? Killing from the air was after all already being practised in Somalia and Iraq in a new and successful pedagogy of control.29 Or would this be felt to be cutting too close to home? If the Irish ranked somewhere above those distant natives in the racial hierarchy, did they rank far enough above to be spared the most advanced techniques of civilization? In short, what was the acceptable level of terror that could be deployed from the perspective of the different national and international constituencies?

The level acceptable to different observers – Irish unionist, Ulster unionist, British military, Tory, Liberal, Labour, Dominion, Irish-American, American – would presumably depend on their perception of the issues involved. What was the ‘terrible’ war to be for? It would not be to force the Irish to accept partition. The delegates had already accepted, gullibly or not, the Treaty with the ‘Boundary Clause’ that they persuaded themselves would revise the line of partition to include the areas contiguous to the border with majority Irish nationalist population. So what else was so sacred, so non-negotiable, for Lloyd George (who was himself personally quite ‘negotiable’ on ‘Ulster’ issues)? Was it to hold ‘Southern Ireland’ at all costs, as a still occupied country, garrisoned with a British army in the twenty-six leftover counties? It was not. The British were prepared to withdraw their army, even if the military clauses of the Treaty guaranteed British military security interests. Nevertheless, it was the end of the Salisbury doctrine in its naked form. Ireland was no longer to be held ‘at all costs’, through permanent military occupation.

But it was still to be held loyal to the Crown by virtue of the oath of fidelity to the king that all members of the Irish parliament would be obliged to take. This was the issue on which Lloyd George issued his ultimatum of 5 December, and the issue above all others that led to the ‘Treaty split’ on the Irish side, and which features regularly in Ernie O’Malley’s thinking.