8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

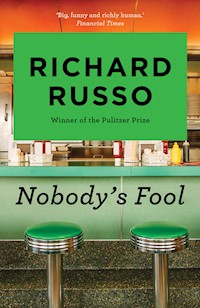

Richard Russo's slyly funny and moving novel follows the unexpected workings of grace in a deadbeat town in upstate New York - and in the life of one of its unluckiest citizens, Sully, who has been doing the wrong thing triumphantly for fifty years. Divorced from his own wife and carrying on halfheartedly with another man's, saddled with a bum knee and friends who make enemies redundant, Sully now has one new problem to cope with: a long-estranged son who is in imminent danger of following in his father's footsteps. With its sly and uproarious humour and a heart that embraces humanity's follies as well as its triumphs, Nobody's Fool is storytelling at its most generous.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

For Jean Levarn Findlay

Contents

Part One

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Part Two

Tuesday

Wednesday

Part Three

Thursday

Friday

Nobody’s Fool

Part One

Wednesday

UPPER MAIN STREET in the village of North Bath, just above the town’s two-block-long business district, was quietly residential for three more blocks, then became even more quietly rural along old Route 27A, a serpentine two-lane blacktop that snaked its way through the Adirondacks of northern New York, with their tiny, down-at-the-heels resort towns, all the way to Montreal and prosperity. The houses that bordered Upper Main, as the locals referred to it—although Main, from its “lower” end by the IGA and Tastee Freez through its upper end at the Sans Souci, was less than a quarter mile—were mostly dinosaurs, big, aging clapboard Victorians and sprawling Greek Revivals that would have been worth some money if they were across the border in Vermont and if they had not been built as, or converted into, two and occasionally three-family dwellings and rented out, over several decades, as slowly deteriorating flats. The most impressive feature of Upper Main was not its houses, however, but the regiment of ancient elms, whose upper limbs arched over the steeply pitched roofs of these elderly houses, as well as the street below, to green cathedral effect, bathing the street in breeze-blown shadows that masked the peeling paint and rendered the sloping porches and crooked eaves of the houses quaint in their decay. City people on their way north, getting off the interstate in search of food and fuel, often slowed as they drove through the village and peered nostalgically out their windows at the old houses, wondering idly what they cost and what they must be like inside and what it would be like to live in them and walk to the village in the shade. Surely this would be a better life. On their way back to the city after the long weekend, some of the most powerfully affected briefly considered getting off the interstate again to repeat the experience, perhaps even look into the real estate market. But then they remembered how the exit had been tricky, how North Bath hadn’t been all that close to the highway, how they were getting back to the city later than they planned as it was, and how difficult it would be to articulate to the kids in the backseat why they would even want to make such a detour for the privilege of driving up a tree-lined street for all of three blocks, before turning around and heading back to the interstate. Such towns were pretty, green graves, they knew, and so the impulse to take a second look died unarticulated and the cars flew by the North Bath exit without slowing down.

Perhaps they were wise, for what attracted them most about the three-block stretch of Upper Main, the long arch of giant elms, was largely a deceit, as those who lived beneath them could testify. For a long time the trees had been the pride of the neighborhood, having miraculously escaped the blight of Dutch elm disease. Only recently, without warning, the elms had turned sinister. The winter of 1979 brought a terrible ice storm, and the following summer the leaves on almost half of the elms strangled on their branches, turning sickly yellow and falling during the dog days of August instead of mid-October. Experts were summoned, and they arrived in three separate vans, each of which sported a happy tree logo, and the young men who climbed out of these vans wore white coats, as if they imagined themselves doctors. They sauntered in circles around each tree, picked at its bark, tapped its trunk with hammers as if the trees were suspected of harboring secret chambers, picked up swatches of decomposing leaves from the gutters and held them up to the fading afternoon light.

One white-coated man drilled a hole into the elm on Beryl Peoples’ front terrace, stuck his gloved index finger into the tree, then tasted, making a face. Mrs. Peoples, a retired eighth-grade teacher who had been watching the man from behind the blinds of her front room since the vans arrived, snorted. “What did he expect it to taste like?” she said out loud. “Strawberry shortcake?” Beryl Peoples, “Miss Beryl” as she was known to nearly everyone in North Bath, had been living alone long enough to have grown accustomed to the sound of her own voice and did not always distinguish between the voice she heard in her ears when she spoke and the one she heard in her mind when she thought. It was the same person, to her way of thinking, and she was no more embarrassed to talk to herself than she was to think to herself. She was pretty sure she couldn’t stifle one voice without stifling the other, something she had no intention of doing while she still had so much to say, even if she was the only one listening.

For instance, she would have liked to tell the young man who tasted his glove and made a face that she considered him to be entirely typical of this deluded era. If there was a recurring motif in today’s world, a world Miss Beryl, at age eighty, was no longer sure she was in perfect step with, it was cavalier open-mindedness. “How do you know what it’s like if you don’t try it?” was the way so many young people put it. To Miss Beryl’s way of thinking—and she prided herself on being something of a free-thinker—you often could tell, at least if you were paying attention, and the man who’d just tasted the inside of the tree and made a face had no more reason to be disappointed than her friend Mrs. Gruber, who’d announced in a loud voice in the main dining room of the Northwoods Motor Inn that she didn’t care very much for either the taste or the texture of the snail she’d just spit into her napkin. Miss Beryl had been unmoved by her friend’s grimace. “What was there about the way it looked that made you think it would be good?”

Mrs. Gruber had not responded to this question. Having spit the snail into the napkin, she’d become deeply involved with the problem of what to do with the napkin.

“It was gray and slimy and nasty looking,” Miss Beryl reminded her friend.

Mrs. Gruber admitted this was true, but went on to explain that it wasn’t so much the snail itself that had attracted her as the name. “They got their own name in French,” she reminded Miss Beryl, stealthily exchanging her soiled cloth napkin for a fresh one at an adjacent table. “Escargot.”

There’s also a word in English, Miss Beryl had pointed out. Snail. Probably horse doo had a name in French also, but that didn’t mean God intended for you to eat it.

Still, she was privately proud of her friend for trying the snail, and she had to acknowledge that Mrs. Gruber was more adventurous than most people, including two named Clive, one of whom she’d been married to, the other of whom she’d brought into the world. Where was the middle ground between a sense of adventure and just plain sense? Now there was a human question.

The man who tasted the inside of the elm must have been an even bigger fool than Mrs. Gruber, Miss Beryl decided, for he’d no sooner made the face than he took off his work glove, put his finger back into the hole and tasted again, probably to ascertain whether the foul flavor had its origin in the tree or the glove. To judge from his expression, it must have been the tree.

After a few minutes the white-coated men collected their tools and reloaded the happy tree vans. Miss Beryl, curious, went out onto the porch and stared at them maliciously until one of the men came over and said, “Howdy.”

“Doody,” Miss Beryl said.

The young man looked blank.

“What’s the verdict?” she asked.

The young man shrugged, bent back at the waist and looked up into the grid of black branches. “They’re just old, is all,” he explained, returning his attention to Miss Beryl, with whom he was approximately eye level, despite the fact that he was standing on the bottom step of her front porch while she stood at the top. “Hell, this one here”—he pointed at Miss Beryl’s elm—“if it was a person, would be about eighty.”

The young man made this observation without apparent misgiving, though the tiny woman to whom he imparted the information, whose back was shaped like an elbow, was clearly the tree’s contemporary in terms of his own analogy. “We could maybe juice her up a little with some vitamins,” he went on, “but—” He let the sentence dangle meaningfully, apparently confident that Miss Beryl possessed sufficient intellect to follow his drift. “You have a nice day,” he said, before returning to his happy tree van and driving away.

If the “juicing up” had any effect, so far as Miss Beryl could tell, it was deleterious. That same winter a huge limb off Mrs. Boddicker’s elm, under the weight of accumulated snow and sleet, had snapped like a brittle bone and come crashing down, not onto Mrs. Boddicker’s roof but onto the roof of her neighbor, Mrs. Merriweather, swatting the Merriweather brick chimney clean off. When the chimney descended, it reduced to rubble the stone birdbath of Mrs. Gruber, the same Mrs. Gruber who had been disappointed by the snail. Since that first incident, each winter had yielded some calamity, and lately, when the residents of Upper Main peered up into the canopy of overarching limbs, they did so with fear instead of their customary religious affection, as if God Himself had turned on them. Scanning the maze of black limbs, the residents of Upper Main identified particularly dangerous-looking branches in their neighbors’ trees and recommended costly pruning. In truth, the trees were so mature, their upper branches so high, so distant from the elderly eyes that peered up at them, that it was anybody’s guess as to which tree a given limb belonged, whose fault it would be if it descended.

The business with the trees was just more bad luck, and, as the residents of North Bath were fond of saying, if it weren’t for bad luck they wouldn’t have any at all. This was not strictly true, for the community owed its very existence to geological good fortune in the form of several excellent mineral springs, and in colonial days the village had been a summer resort, perhaps the first in North America, and had attracted visitors from as far away as Europe. By the year 1800 an enterprising businessman named Jedediah Halsey had built a huge resort hotel with nearly three hundred guest rooms and named it the Sans Souci, though the locals had referred to it as Jedediah’s Folly, since everyone knew you couldn’t fill three hundred guest rooms in the middle of what had so recently been wilderness. But fill them Jedediah Halsey did, and by the 1820s several other lesser hostelries had sprung up to deal with the overflow, and the dirt roads of the village were gridlocked with the fancy carriages of people come to take the waters of Bath (for that was the village’s name then, just Bath, the “North” having been added a century later to distinguish it from another larger town of the same name in the western part of the state though the residents of North Bath had stubbornly refused the prefix). And it was not just the healing mineral waters that people came to take, either, for when Jedediah Halsey, a religious man, sold the Sans Souci, the new owner cornered the market in distilled waters as well, and during long summer evenings the ballroom and drawing rooms of the Sans Souci were full of revelers. Bath had become so prosperous that no one noticed when several other excellent mineral springs were discovered a few miles north near a tiny community that would become Schuyler Springs, Bath’s eventual rival for healing waters. The owners of the Sans Souci and the residents of Bath remained literally without care until 1868, when the unthinkable began to happen and the various mineral springs, one by one, without warning or apparent reason, began, like luck, to dry up, and with them the town’s wealth and future.

As luck (what else would you call it?) would have it, the upstart Schuyler Springs was the immediate beneficiary of Bath’s demise. Even though their origin was the same fault line as the Bath mineral springs’, the Schuyler springs continued to flow merrily, and so the visitors whose fancy carriages had for so long pulled into the long circular drive before the front entrance of the Sans Souci now stayed on the road another few miles and pulled into the even larger and more elegant hotel in Schuyler Springs that had been completed (talk about luck!) the very year that the springs in Bath ran dry. Well, maybe it wasn’t exactly luck. For years the town of Schuyler Springs had been making inroads, its down-state investors and local businessmen promoting other attractions than those offered by the Sans Souci. In Schuyler Springs there were prize-fights held throughout the summer season, as well as gambling, and, most exciting of all, a track was under construction for racing Thoroughbred horses. The citizens of Bath had been aware of these enterprises, of course, and had been watching, gleefully at first, and waiting for them to fail, for the schemes of the Schuyler Springs group struck them as even more foolish than the Sans Souci with its three hundred rooms had been. There was certainly no need for two resorts, two grand hotels, within so small a geographical context. Which meant that Schuyler Springs was doomed. There were limits to folly. True, Jedediah Halsey’s Sans Souci hadn’t been so much foolish as “visionary,” which, as everyone knew, was what you called a foolish idea that worked anyway. And, people were quick to point out after the springs ran dry and the visitors moved on, the Sans Souci hadn’t so much worked as it had enjoyed temporary success. The vast majority of its nearly five hundred rooms (for the hotel had expanded on a very grand scale, not three years before the springs went dry) were now empty, just as everyone had originally predicted they would be. And so people began to congratulate themselves on their original wisdom, and the residents of the once lucky, now tragically unlucky, community of Bath sat back and waited for their luck to change again. It did not.

By 1900 Schuyler Springs had swept the field of its competitors. The Sans Souci fire of 1903 was the symbolic finish, but of course the battle had long been lost, and most everyone agreed that you couldn’t really count the Sans Souci fire as bad luck, since the blaze had almost certainly been started by the hotel’s owner in order to collect the insurance. The man had died in the blaze, apparently trying to get it started again after it became clear that the wind had shifted and that only the old original wooden structure not the newer, grander addition, was going to burn unless he did something creative. There is always the problem of defining luck as it applies to humans and human endeavors. The wind changing when you don’t want it to could be construed as bad luck, but what of a man frantically rolling a drum of fuel too close to the flames he himself has set? Is he unlucky when a spark sends him to eternity?

In any case, the town of North Bath, now, in the late autumn of 1984, was still waiting for its luck to change. There were encouraging signs. A restored Sans Souci, what was left of it, was scheduled to reopen in the summer, and a new spring had been successfully drilled on the hotel’s extensive grounds. And luck, so the conventional wisdom went, ran in cycles.

The morning of the day before Thanksgiving, five winters after that first elm turned on the residents of Upper Main, cleaving old Mrs. Merriweather’s roof and reducing Mrs. Gruber’s birdbath to rubble, Miss Beryl, always an early riser, awoke even earlier than usual, with a vague sense of unease. As she sat at the edge of her bed trying to trace its source, she had a nosebleed, a real gusher. It came upon her quickly and was just as quickly finished. She caught most of the blood with a swatch of tissue from the box she kept on her bedstand, and as soon as her nose stopped bleeding she flushed the tissue emphatically down the toilet. Was it the quick disappearance of the evidence or the nosebleed itself that left her feeling refreshed? She wasn’t sure, but she felt even better after she’d bathed and dressed, and when she went into her front room to drink her tea, she was surprised and delighted to discover that it had snowed during the night. Nobody had predicted snow, but there it was anyway, the kind of heavy wet snow that sits up tall on railings and tree branches, the whole street white. In the gray predawn, everything outside looked otherworldly, and she watched the dark street and sipped her tea until a car slalomed silently by, leaving its track in the fresh snow, and the vague sense of unease she’d felt upon waking returned, though not as urgently. Who will it be this winter? she wondered, parting the blinds so she could see up into the trees.

Though Miss Beryl was far too close an observer of reality to credit the idea of divine justice in this world, there were times when she could almost see God’s design hovering just out of sight. So far, she’d been lucky. God had permitted tree limbs to fall on her neighbors, not herself. But she doubted He would continue to ignore her in this business of falling limbs. This winter He’d probably lower the boom.

“This’ll be my year,” she said out loud, addressing her husband, Clive Sr., who sat on the television, smiling at her wisely. Dead now for twenty years, Clive Sr. could boast an even temperament. From his vantage point behind glass, nothing much got to him, and if he worried that this might be his wife’s winter, he didn’t show it. “You hear me, star of my firmament?” Miss Beryl prodded. When Clive Sr. had nothing to offer on this score, Miss Beryl frowned at him. “I might as well talk to Ed,” she told her husband. “Go ahead, then,” Clive Sr. seemed to say, safe behind his glass.

“What do you think, Ed?” Miss Beryl asked. “Is this my year?”

Driver Ed, Miss Beryl’s Zamble mask, stared down at her from his perch on the wall. Ed had a dour human face modified by antelope horns and a toothed beak, all of which added up, to Miss Beryl’s way of thinking, to a mortified expression. He looked, Miss Beryl had insisted when she purchased Ed over twenty years ago, like Clive Sr. had looked when he discovered he was going to be required to teach driver education at the high school. Clive Sr. had been the football coach, and his later years had not gone the way he’d planned. First, when the football team had begun to lose, he’d been required to teach civics, and when it continued to lose, he’d been required to teach driver education. Eventually, football had been dropped, a victim of declining postwar enrollments, demographic shifts, and continued humiliation at the hands of archrival Schuyler Springs, leaving Miss Beryl’s husband bewildered and adrift. Driver ed turned out to be the death of him when a girl named Audrey Peach, without warning or reason, braked Clive Sr. through the front windshield of a brand-new driver ed car early one morning before he was entirely awake. Clive Sr. never wore a seat belt. He made sure his student drivers and passengers wore them, but he himself disliked the sensation of restraint. The way Clive Sr. looked at it, once he got wedged into a compact car, there was no place for him to go. A big man, he required a big car, and he suspected that the little piece of shit driver ed car the school board had purchased was a punishment for the losing seasons he was now suffering in basketball, a sport he didn’t even like. Once inside the compact car, he felt so claustrophobic it was hard to concentrate on his teaching. The low roof required him to hunch forward to see where young Audrey Peach was pointed. When she hit the new brakes, the little car stopped impressively, but Clive Sr. kept going, his bullet-shaped skull punching right through the windshield, where he lodged, briefly, like a sinner in the stocks, until the car rocked and flung him back into his seat, neck broken, a bloody object lesson and the only driver ed teacher in upstate New York ever to be killed in the line of duty.

“See?” Miss Beryl addressed her husband’s photograph. “Ed thinks so too.”

At least, she comforted herself, when the divine boom got lowered she’d be in better financial condition to receive it than many of her neighbors. She could congratulate herself that she was not only well insured but reasonably secure. Miss Beryl, like so many of the owners of the houses along Upper Main, was a widow, technically not “Miss” Beryl at all, and her husband had left her in possession of both his VA pension and retirement, which, together with her own retirement and Social Security, added up, and she knew herself to be far better off than Mrs. Gruber and the others. Life, which in Miss Beryl’s considered opinion tilted in the direction of cruelty, had at least spared her financial hardship, and she was grateful.

In other respects life had been less kind. Her being known in North Bath as “Miss” Beryl derived from the fact that the militantly unteachable eighth-grade schoolchildren she’d instructed for forty years considered her far too odd looking and misshapen to have a husband. They refused to believe it, in fact, even when confronted with irrefutable evidence. They instinctively called her Miss Peoples or Miss Beryl on the first day of class and paid no attention when she corrected them. Clive Sr. was of the opinion that kids just naturally thought of their teachers as spinsters, and he had found the whole thing amusing, often referring to her as “Miss Beryl” himself. Clive Sr. had not been a profoundly stupid man, but he missed his fair share of what Miss Beryl referred to as life’s nuances, and one of the nuances he missed was the hurt he thoughtlessly inflicted on his wife when he called her by that name, a name that suggested he saw her the same way other people did. Clive Sr. was the only man who’d ever treated Miss Beryl as desirable, and it seemed to her almost unforgivable that he should, without thinking, take back the gift of his love for her in this one small way, take it back repeatedly, always with a big grin.

But he had loved her. This she knew, and the knowledge was another of the ways she was better off than most of her neighbors, whose husbands, when they died, left their widows alone and largely unprepared for another decade or two of solitary existence. Mrs. Gruber, for instance, had never worked outside the home and had little notion how the world operated beyond the obvious fact that it was getting more expensive. Indeed, Miss Beryl was the only professional woman among these frightened Upper Main Street widows. Alive, their husbands had protected them from life’s falling limbs, but now their veteran’s benefits and meager Social Security did not stretch very far, and so they rented their second-floor flats out of necessity, though the rents they received often did little more than cover the repairs necessitated by the disintegration of hundred-year-old pipes, the overloading of antiquated electrical circuits, the falling of tree limbs. To make matters worse, taxes were skyrocketing, pressured upward by down-state speculators in real estate, many of whom seemed convinced that Bath and every other small town in the corridor between New York City and Montreal would appreciate dramatically during the eighties and nineties. It might not look it, but Bath had much to recommend it. Not only was the old Sans Souci, grandly restored, scheduled to reopen next summer, but a huge tract of boggy land between the village and the interstate was being considered for development of a theme park called The Ultimate Escape. Miss Beryl’s son, Clive Jr., for the last decade the president of the North Bath Savings and Loan, was leading a group of local investors to ensure that the theme park became a reality, and he subscribed enthusiastically to the view that because land was limited, the future was limitless. “In twenty years,” he was fond of saying, “there’s going to be no such thing as a bad location.”

Miss Beryl did not argue, but neither did she share her son’s optimism. To her way of thinking there would always be bad locations, and unless she was gravely mistaken Clive Jr. would discover this by investing in them. Clive Jr. was a cynical optimist. He believed that people went broke for two reasons: stupidity and small thinking. Stupidity in others was a good thing, according to Clive Jr., because there was money to be made by it. Other people’s financial failures were opportunities, not cause for alarm. He liked to analyze failure after the fact, discover its source in small thinking, limited ambition, penny antes. He prided himself on having rescued the North Bath Savings and Loan from just such unhealthy notions. For years that institution had been edging by slender centimeters toward insolvency, the result of Clive Jr.’s predecessor, a deeply suspicious and pessimistic man from Maine who hated to loan people money. The fact that people came to him asking for money and often truly needing it suggested to him the likelihood of their not being able to repay it. He could see the need in their eyes, and he couldn’t imagine such need going away. He thought the institution’s money was safer in the vault than in their pockets. The man had actually died in the bank, on a Sunday, seated in his leather chair, his office door closed, as it always was, as if he suspected he might be petitioned even on a weekend night with the doors to the bank locked. He was discovered on Monday morning in a state of advanced rigor mortis not unlike, it was later remarked, the condition of the institution he oversaw.

When Clive Jr. took over, things loosened up right away. The first thing he did was put down a new carpet in the lobby, the old one having evolved several stages beyond threadbare except in the passageway that led to the CEO’s office, where there’d been little traffic. His goal for the decade was to increase tenfold the savings and loan’s assets, and he made known his intention to invest what money was left aggressively and even, when the situation seemed to call for it, to loan money out. After so many years of pessimism, Clive Jr. maintained, it was time for a little optimism. Furthermore, that was the mood of the nation.

The only policy Clive Jr. shared with his late predecessor was his deep distrust of the residents of North Bath, whom both men considered shiftless. That’s the way his high school classmates had been, and they’d grown up shiftless, in Clive Jr.’s view. He preferred to deal with investors and borrowers from downstate, indeed from out of state, indeed from as far away as Texas, convinced that these were the future of Bath, just as they had been the salvation of Clifton Park and the other recently affluent Albany suburbs. “Downstate money is creeping up the Northway,” Clive Jr. told his mother, a remark that always caused her to peer at him over the rims of her reading glasses. To Miss Beryl, the idea of money creeping up the interstate was sinister. “Ma,” he insisted, “take it from me. When the time comes to sell the house, you’re going to make a bundle.”

It was phrases like “when the time comes” that worried Miss Beryl. They had a menacing resonance when Clive Jr. delivered them. She wondered what he had in mind. Would she be the judge of “when the time came,” or would he? When he visited her, he looked the house over with a realtor’s eye, found excuses to go down into the basement and up into the attic, as if he wanted to make sure that “when the time came” for him to inherit his mother’s property it would be in good condition. He objected to her renting the upstairs flat to Donald Sullivan, against whom Clive Jr. harbored some ancient animosity, and no visit from Clive Jr., no matter how brief, passed without a renewed plea for her to throw Sully out before he fell asleep in bed with a lighted cigarette. Something about the way Clive Jr. voiced this concern convinced Miss Beryl that her son’s anxiety had less to do with the possibility that his elderly mother might go up in flames than that the house would.

Miss Beryl was not proud of entertaining such unkind thoughts about her only child, and at times she even tried to reason herself out of them and into more natural maternal affection. The only difficulty was that natural maternal affection did not come naturally where Clive Jr. was concerned. The Clive Jr. who sat on the television opposite his father seemed pleasant enough, and the face the camera caught did not seem to be that of an unhappy, insecure, middle-aged banker. In fact, Clive Jr.’s face, still boyish in some ways, seemed full of possibility at an age where the countenances of most men were etched indelibly by the certainties of their existences. Clive Jr., at least the Clive Jr. who sat on the television, still struck Miss Beryl as unresolved, even though he would be fifty-six on his next birthday. Clive Jr. in real life was a different story. Whenever he appeared for one of his visits and gave Miss Beryl a dry, unpleasant peck on the forehead before scanning the living room ceiling for water damage, his character, if character was the right word, seemed as fixed and settled as a fifth-term conservative politician’s. She endured his visits, his endless financial advice, with as much good cheer as she could muster. He would tell her what to do and why, and she would listen politely for as long as it took before declining to follow his advice. In her opinion Clive Jr. was full of cockamamie schemes, and he treated each as if its origin were the burning bush and not his own fevered brain. “Ma,” he often said, on those occasions when she emphatically declined to follow his advice, “it’s almost as if you didn’t trust me.”

“I don’t trust you,” Miss Beryl said aloud, addressing her son’s photo on the television, then adding, to her husband, “I’m sorry, but I can’t help it. I don’t trust him. Ed understands, don’t you, Ed.”

Clive Sr. just smiled back, a tad ruefully, it seemed to her. Since his death he’d increasingly taken their son’s side in matters of conflict. “Trust him, Beryl,” he whispered to her now, his voice confidential, as if he feared that Driver Ed might overhear. “He’s our son. He’s the star of your firmament now.”

“I’m working on it,” Miss Beryl assured her husband, and in fact, she was. She’d loaned Clive Jr. money twice during the last five years and not even asked him what he intended to do with it. Five thousand dollars the first time. Ten thousand the second. Amounts she would not be pleased to lose but which, truth be told, she could afford to lose. But both times Clive Jr. had paid her back when he said he would, and Miss Beryl, on the lookout for a reason not to trust her son, discovered that she was mildly disappointed to have the money back in her own possession. In fact, she was unable to fend off a particularly shameful suspicion—that Clive Jr. had not needed the money at all, that he’d borrowed it to demonstrate to her that he was trustworthy. She even began to suspect that what he must be after was not part of what would be his soon enough, but rather control of the whole. But to what end? Miss Beryl had to admit that the logic of her suspicions was flawed. After all, her money, the house on Upper Main and its considerable contents, everything would belong to Clive Jr. eventually, when, as he put it, “the time came.”

One of the things that drove her son to distraction, Miss Beryl suspected, was not knowing how much “everything” amounted to. There was the house, of course, and the ten thousand dollars he knew his mother had because she’d loaned it to him. But how much more? It was this information about her finances that Miss Beryl did not trust her son with. She had an accountant in Schuyler Springs do her taxes each year, and she instructed him to surrender no information about her affairs to Clive Jr. For legal advice, she dealt with a local attorney named Abraham Wirfly, whom her son continued to warn her against as an incompetent and a drunkard. Miss Beryl was not unaware of Mr. Wirfly’s shortcomings, but she steadfastly maintained that he was not so much incompetent as unambitious, a character trait almost impossible to find in a lawyer. More important, she considered the man to be absolutely loyal, and when he promised to divulge nothing of her financial and legal affairs to Clive Jr., she believed him. Without ever saying so, Abraham Wirfly seemed also to entertain reservations about Clive Jr., and so Miss Beryl continued to trust him. Clive Jr.’s growing exasperation was testimony to her excellent judgment. “Ma,” he pleaded pitifully, pacing up and down the length of her front room, “how can I help you protect your assets if you won’t let me? What’s going to happen if you get sick? Do you want the hospital to take everything? Is that your plan? To have a stroke and let some hospital take their thousand a day until it’s all gone and you’re destitute?”

The logic of her son’s concern was inescapable, his argument consistent, yet despite this, Miss Beryl could not shed the feeling that Clive Jr. had a hidden agenda. She knew no more about his personal finances than he knew about hers, but she suspected that he was well on his way to becoming a wealthy man. She knew too that despite his realtor’s eye, he had no interest in the house, that if he were to inherit it tomorrow, he’d sell it the day after. He’d recently purchased a luxury town home at the new Schuyler Springs Country Club between North Bath and Schuyler Springs. The house on Upper Main might bring a hundred and fifty thousand dollars, maybe more, and this was nothing to sneeze at, even if Clive Jr. didn’t “need” the money. Yet she was unable to accept at face value that this was her son’s design. There was something about the way his eye roved uncomfortably from corner to corner of each room, as if in search of spirit trails, that convinced Miss Beryl he was seeing something she couldn’t see, and until she discovered what it was, she had no intention of trusting him fully.

Outside Miss Beryl’s front window a thick clump of snow fell noiselessly from an unseen branch. There was a lot of it, but the snow wouldn’t stay. Despite appearances, this wasn’t real winter. Not yet. Still, Miss Beryl went out into the back hall and located the snow shovel where she had stored it beneath the stairs last April and leaned it up against the door where even Sully couldn’t fail to see it when he left. Back inside, she became aware of a distant buzzing which meant that her tenant’s alarm had gone off. Since injuring his knee, Sully slept even less than Miss Beryl, who got by on five hours a night, along with the three or four fifteen-minute naps she adamantly refused to admit taking throughout the day. Sully woke up several times each night. Miss Beryl heard him pad across his bedroom floor above her own and into the bathroom, where he would patiently wait to urinate. Old houses surrendered a great many auditory secrets, and Miss Beryl knew, for instance, that Sully had recently taken to sitting on the commode, which creaked beneath him, to await his water. Sometimes, to judge from the time it took him to return to bed, he fell asleep there. Either that or he was having prostate problems. Miss Beryl made a mental note to share with Sully one of the ditties of her childhood:

Old Mrs. Jones had diabetes

Not a drop she couldn’t pee

She took two bottles

Of Lydia Pinkham’s

And they piped her to the sea.

Miss Beryl wondered if Sully would be amused. That probably depended on whether he knew what Lydia Pinkham’s was. One of the problems of being eighty was that you built up a pretty impressive store of allusions. Other people didn’t follow them, and they made it clear that this was your fault. Somewhere along the line, about the time America was being colonized, Miss Beryl suspected, the knowledge of old people had gotten discounted until now it was worth what the little boy shot at. Had Miss Beryl been a younger woman, it might have made an interesting project to trace the evolution of conventional wisdom on this point. Somehow old people, once the revered repositories of the culture’s history and values, had become dusty museums of arcane and worthless information. No matter. She’d share the jingle with Sully anyway. He could stand a little poetry in his life.

Upstairs, the alarm clock continued to buzz. According to Sully, the only deep sleep he got any more was during the hour or so before his alarm went off. He’d recently purchased a new alarm clock because he kept sleeping through the old one. Also the new one. The first time Miss Beryl had heard that strange, faraway buzzing, she’d mistakenly concluded that the end was near. She’d read somewhere that the human brain was little more than a maze of electrical impulses, firing dutifully inside the skull, and the buzzing, she concluded, must be some sort of malfunction. The fact that the buzzing occurred at the same time every morning did not immediately tip her off, as it should have, that it was external to herself. She’d assumed that the time Clive Jr. was always alluding to had indeed come. It was the abrupt cessation of the buzzing, always followed immediately by the thud of Sully’s heavy feet hitting the bedroom floor, that finally allowed Miss Beryl to solve the mystery, for which she was grateful, because, having solved it, she could stop worrying and shaking her head in search of the electrical short and giving herself headaches.

Perhaps because of her original misdiagnosis, the distant buzzing of Sully’s alarm was still mildly disconcerting, so she did this morning what she did most mornings. She went first to the kitchen for the broom, then to her bedroom, where she gave the ceiling a good sharp thump or two with the broom handle, stopping when she heard her tenant grunt awake, snorting loudly and confused. She doubted Sully was aware of what really woke him so many mornings, that it was not the new alarm.

Perhaps, Miss Beryl conceded, her son was right about giving Sully the boot. He was a careless man, there was no denying it. He was careless with cigarettes, careless, without ever meaning to be, about people and circumstances. And therefore dangerous. Maybe, it occurred to Miss Beryl as she returned to her front window and stared up into the network of black limbs, Sully was the metaphorical branch that would fall on her from above. Part of getting old, she knew, was becoming unsure. For longer than any of her widowed neighbors, Miss Beryl had staved off the ravages of uncertainty by remaining intellectually challenged and alert. So far she’d been able to keep faith in her own judgment, in part by rigorously questioning the judgment of others. Having Clive Jr. around helped in this regard, and Miss Beryl had always told herself that when her son’s advice started making sense to her, then she’d know she was slipping. Perhaps her fearing Clive Jr.’s wisdom on the subject of Sully was the beginning.

But she’d not concede quite yet, she decided. In several important respects Sully was an important ally, just as he had been a month ago when she’d taken a tumble and sprained her wrist painfully. Fearing it might be broken, she’d had Sully drive her to the hospital in Schuyler Springs, where the wrist had been X-rayed and taped. The whole episode had taken no more than two hours, and she’d been sent home with a prescription for Tylenol 3 painkillers. She’d taken only two of the pills because they made her drowsy and she didn’t mind the pain once she knew what it was. As soon as she’d learned the wrist wasn’t fractured, she felt better, and the next day she made a gift of the remaining Tylenols to Sully, who since his injury was always in the market for pain pills.

Sully could be trusted, she knew, to keep her secret. She wished the same could be said for Mrs. Gruber, whom Clive Jr. used, Miss Beryl suspected, to check up on her. Mrs. Gruber denied this, of course, but then she would, having been forbidden by her friend to communicate any information of a personal nature to Clive Jr. But Miss Beryl was pretty sure Mrs. Gruber was a snitch just the same. Clive Jr. could be ingratiating, and one of Mrs. Gruber’s chief enjoyments in life was discussing other people’s illnesses and accidents. Miss Beryl doubted that her friend could resist an insidious sweet-talker like Clive Jr.

Still at the front window, Miss Beryl peered for a long time through the blinds and up the street in the direction of Mrs. Gruber’s house. Quarter to seven. The street was still silent, the new blanket of snow spoiled by just the one set of dark tire tracks. Miss Beryl sighed and stared up into the web of tree limbs, starkly black against the white morning sky. “Fall,” she said, pleased and heartened as she always was by the sound of her own decisive voice. “See if I care.”

“You probably wouldn’t care if I fell,” said a voice behind her. “I bet you’d laugh, in fact.”

Miss Beryl had been so preoccupied with her thoughts, she had not heard her living room door open or her tenant enter. It seemed only a few seconds before that she’d heard him snort awake in the upstairs bedroom, surely not enough time to rise, dress, do all the early morning things a civilized person had to do. But of course men were strange creatures and not, strictly speaking, civilized at all, most of them. The one she saw standing before her in his stocking feet, work boots dangling from their leather laces, had no doubt simply rolled out of bed and into his clothes. She doubted he wore pajamas, probably slept in his shorts the way Clive Sr. had, then grabbed the first pair of trousers he saw, the ones draped across a chair or over the bottom of the bed. Knowing Sully, he probably slept in his socks to save time.

Not that her tenant was much worse than most men. He had the laborer’s habit of bathing after his day’s work was done instead of in the morning, which meant that when he awoke he had only two immediate needs—to relieve himself and to locate a cup of coffee. In Sully’s case the coffee was two blocks away at Hattie’s Lunch, and he often arrived there before he was completely awake. He left his work boots downstairs in the hall by the back door. For some reason he liked to put them on in Miss Beryl’s downstairs flat rather than his own. The boots always left a dirty trail, in winter a muddy print on the hardwood floor, in summer a dry cluster of tiny pebbles which Miss Beryl would sweep into a dustpan when he’d left. Men in general, Miss Beryl had observed, seldom took note of what they trailed behind them, but Sully was particularly oblivious, his wake particularly messy. Still, Miss Beryl wouldn’t have given a nickel for a fastidious man, and she didn’t mind cleaning up after Sully each morning. He provided her a small task, and her days had few enough of these. “Lordy,” Miss Beryl said. “Sneak up on an old woman.”

“I thought you were talking to me, Mrs. Peoples,” Sully told her. He was the only person she knew who called her “missus,” and the gesture reserved for him a special place in Miss Beryl’s heart. “I just thought I’d stop in to make sure you didn’t die in your sleep.”

“Not yet,” she told him.

“You’re talking to yourself, though,” he pointed out, “so it can’t be long.”

“I wasn’t talking to myself. I was talking to Ed,” Miss Beryl informed her tenant, indicating Ed on the wall.

“Oh,” Sully said, feigning relief. “And here I thought you were going batty.”

He sat down heavily on Miss Beryl’s Queen Anne chair, causing her to wince. The chair was delicate, a gift from Clive Sr., who had bought it for her at an antique shop in Schuyler Springs. She had talked him into buying it, actually. Clive Sr. had thought it too fragile, with its slender curved legs and arms. A large man, he’d pointed out that if he ever sat in it, “the damn thing” would probably collapse and run him through. “It wasn’t my intention for you to sit in it, ever,” Miss Beryl had informed him. “In fact, it wasn’t my intention for anyone to sit in it.” Clive Sr. had frowned at this intelligence and opened his mouth to say the obvious—that it didn’t make a lot of sense to buy a chair nobody was going to sit in—when he noticed the expression on his beloved’s face and shut his mouth. Like many men addicted to sports, Clive Sr. was also a religious man and one who’d been raised to accept life’s mysteries—the Blessed Trinity, for one instance, a woman’s reasoning, for another. Also, he remembered just in time that Miss Beryl had made him a present, just that winter, of what she referred to as the world’s ugliest corduroy recliner, the very one he had his heart set on. To Clive Sr.’s way of thinking, there was nothing ugly about the chair, and it was certainly more substantial, with its solid construction and foam padding and sturdy fabric, than this pile of skinny mahogany sticks, but he guessed that he was had, and he wrote out the check.

Both had been correct, Miss Beryl now reflected. The corduroy recliner, safely out of sight in the spare bedroom, was the ugliest chair in the world, and the Queen Anne was fragile. She hated for anyone, much less Sully, to sit in it. There were many rudimentary concepts that eluded her tenant, and pride of ownership was among these. Sully himself owned nothing that he placed any value on, and it always seemed inexplicable to him that people worried about harm coming to their possessions. His existence had always been so full of breakage that he viewed it as one of life’s constants and no more worth worrying about than the weather. Once, years ago, Miss Beryl had broached this touchy subject with Sully, tried to indicate those special things among her possessions that she would hate to see broken, but the discussion appeared to either bore or annoy him, so she’d given up. She could, of course, ask him not to sit in this one particular chair, but the request would just irritate him and he wouldn’t stop in for a while until he forgot what she’d done to irritate him, and when he returned he’d go right back to the same chair.

So Miss Beryl decided to risk the chair. She enjoyed her tenant’s stopping by in the morning “to see if she was dead yet” because she’d always been fond of Sully and understood his fondness for her as well. Affection wasn’t the sort of thing men like Sully easily admitted to, and of course he’d never told her he was fond of her, but she knew he was, just the same. In some respects he was the opposite of Clive Jr., who steadfastly maintained that he visited her out of affection and concern but who was visibly impatient from the moment he lumbered up her porch steps. He was always on his way somewhere else, and the mere sight of his mother seemed to satisfy him, as did the sound of her voice on the telephone, and so Miss Beryl was unable to fend off the suspicion whenever the phone rang and the caller hung up without speaking that it was Clive Jr. calling to ascertain the fact of his mother’s continued existence.

“Could I interest you in a nice hot cup of tea?” Miss Beryl said, watching apprehensively as the Queen Anne protested under Sully’s squirming weight.

“Not now, not ever,” Sully told her, his forehead perspiring. Getting into and out of his boots was one of the day’s more arduous tasks. The good leg wasn’t that difficult, but the other, since fracturing the kneecap, remained stiff and painful until midmorning. This early, about all he could do was loosen the laces all the way and work his foot into the opening as best he could. He’d locate the shoe’s tongue and laces later. “I’ll take my usual cup of coffee, though.”

He was having such a terrible time with the boot, she said, “I suppose I could make a pot of coffee.”

He rested a moment, grinned at her. “No thanks, Beryl.”

“How come you’re wearing your clodhoppers?” Miss Beryl wondered. In fact, Sully was dressed in preaccident attire—worn gray work pants, faded denim shirt over thermal underwear, a quilted, sleeveless vest, a bill cap. Since September he’d dressed differently to attend the classes in refrigeration and air-conditioning repair he took at the nearby community college as part of the retraining program that was a stipulation of his partial disability payments.

Sully stood—Miss Beryl wincing again as he placed his full weight on the arms of the Queen Anne—and, having inserted his toes into the unlaced work boot, scuffed it along the hardwood floor until he managed to pin it against the wall and force the entire foot in. “About time I went back to work, don’t you think?” he said.

“What if they find out?”

He grinned at her. “You aren’t going to squeal on me, are you?”

“I should,” she said. “There’s probably a reward for turning people like you in. I could use the money.”

Sully studied her, nodding. “Good thing Coach kicked off before he found out how mean you’d get in your old age.”

Miss Beryl sighed. “I can’t suppose it would do any good to point out the obvious.”

Sully shook his head. “Probably not. What’s the obvious?”

“That you’re going to hurt yourself. They’ll stop paying for your schooling, and you’ll be even worse off.”

Sully shrugged. “You could be right, Beryl, but I think I’ll try. Anymore my leg hurts just as bad when I sit around as when I stand, so I might as well stand. I’ve pretty much decided I don’t want to fix air conditioners for the rest of my life.”

He stomped his boot a couple times to make sure his foot was all the way in, rattling the knickknacks. “I swear to Christ, though. If you could learn to put this shoe on for me mornings, I’d marry you and learn to drink tea.”

When Sully collapsed, exhausted, back into the Queen Anne and took out his cigarettes, Miss Beryl headed for the kitchen, where she kept her lone ashtray. Sully was the only person she allowed to smoke in her house, this exception granted on the grounds that he honestly couldn’t remember that she didn’t want him to. He never took note of the fact that there were no ashtrays. Indeed, it never occurred to him even to look for one until the long gray ash at the end of his cigarette was ready to fall. Even then Sully was not the sort of man to panic. He simply held the cigarette upright, as if its vertical position removed the threat of gravity. When the ash eventually fell anyway, he was sometimes quick enough to catch it in his lap, where the ash would stay until, having forgotten about it again, he stood up.

By the time Miss Beryl arrived back with the crystal ashtray she’d bought in London five years before, Sully already had a pretty impressive ash working. “So,” Sully said, “you decide where you’re going this year?”

Every winter for the past twenty, Miss Beryl had sallied forth, as she called it, around the first of the year, returning sometime in March when winter’s back was broken. Her flat was crowded with the souvenirs from these excursions—her walls adorned with an Egyptian spear, a Roman breastplate, a bronze dragon, tiki torches, her flat table surfaces crowded with Wedgwood, an Etruscan spirit boat, a two-headed Foo dog, the floor with wicker elephants, terra-cotta pots, a wooden sea chest. In the months preceding her safaris, she read travel books on her destination. This year she’d checked out books on Africa, where she hoped to find a companion for Driver Ed, who had been purchased in Vermont, actually, and might or might not have been authentic Zamble. Vermont had been about as far as she’d ever been able to convince Clive Sr. to sally forth. He didn’t like to go anywhere people wouldn’t recognize him as the North Bath football coach, which put them on a pretty short leash.

“I’m staying put this winter,” she told Sully, surprised to discover that she’d come to this decision just a few minutes before while looking up into the trees.

“That must mean you’ve been everywhere,” Sully said.

“The early snow convinced me that this is our winter. God’s going to lower the boom. One of those limbs is going to come crashing down on us.”

“Sounds like a good reason to head for the Congo,” Sully offered.

“There’s no such place as the Congo anymore.”

“No?”

“No. And besides,” Miss Beryl reminded him, “God finds Jonah even in the belly of a whale.”

Sully nodded. “God and the cops. That’s how come I stay close to home. So they know where to find me. Maybe that way they’ll go easy.”

Miss Beryl frowned at him. “You’re not in Dutch with the police again, are you, Donald?” Her tenant did wind up in jail occasionally, usually for public intoxication, though when he was younger he’d been a brawler.

Sully grinned at her. “Not to my knowledge, Mrs. Peoples. These days I try to be good. I’m not a young man anymore.”

“Well,” she said, “you were a bad boy far longer than most.”

“I know it,” he said, taking another drag on his cigarette and noticing for the first time how hazardously long the gray ash had become. “You going out for Thanksgiving, at least?”

Miss Beryl took the cigarette from him, put it into the ashtray, and then put the ashtray on the side table. With Sully, you didn’t just set the ashtray down nearby and expect him to recognize its function. “Mrs. Gruber and I are going to the Northwoods Motor Inn. They’re having a buffet. All the turkey and trimmings you can eat for ten dollars.”

Sully exhaled smoke through his nose. “Sounds like a hell of a good deal for the Northwoods. You and Alice couldn’t eat ten dollars’ worth of turkey if they gave you the whole weekend.”

Miss Beryl had to admit this was true. “Mrs. Gruber likes it there. It’s all old fogies like us, and they don’t play loud music. They have a big salad bar, and Mrs. Gruber likes to try everything on it. Snails even.”

“Snails are good, actually,” Sully said, surprising her.

“When did you ever eat a snail?”

Sully scratched his unshaven chin thoughtfully at the recollection. “I liberated France, if you recall. I wish snails were the worst thing I ate between Normandy and Berlin, too.”

“It must be true what they say, then,” Miss Beryl observed. “War is heck. If you ate anything worse than a snail, don’t tell me about it.”

“Okay,” Sully said agreeably.

“I just eat a couple of those carrot curls and save myself for the dinner. Otherwise, I get full, and if I eat too much I get gas.”

Sully stubbed out his cigarette. “Well, in that case, go slow,” he said, laboring to his feet again. “Remember, you got somebody living above you. It’s too cold to open all the windows.”

Miss Beryl followed him out into the hall, his untied shoelaces clicking along the floor.

“I’ll shovel you out after I’ve had my coffee,” he said, noticing the shovel she’d leaned against the wall. “You got anywhere to go right away?”

Miss Beryl admitted she didn’t.

Until he hurt his knee, Sully had been much envied as a tenant by the other widows along Upper Main. Many of them tried to work out reduced rent arrangements with single men, who then shoveled the sidewalk, mowed the lawn and raked leaves in return. But finding the right single man was not easy. The younger ones were forgetful and threw parties and brought young women home with them. The older men were given to illnesses and complications of the lower back. Single, able-bodied men between the ages of forty-five and sixty were so scarce in Bath that Miss Beryl had been envied Sully for over a decade, and she suspected some of her neighbors were privately rejoicing now that Sully was hobbled. Soon he would be useless, and Miss Beryl would be paid back for years of good fortune by having to carry a renter who couldn’t perform. Indeed, it seemed to Miss Beryl, who saw Sully every day, that he had failed considerably since his accident, and she feared that some morning he wasn’t going to stick his head in to find out if she was dead and the reason was going to be that he was dead. Miss Beryl had already outlived a lot of people she hadn’t planned to outlive, and Sully, tough and stubborn though he was, had a ghostly look about him lately.

“Just don’t forget me,” she told him, recollecting that she would need to go to the market later that morning.

“Do I ever?”

“Yes,” she said, though he didn’t often.

“Well, I won’t today,” he assured her. “How come you aren’t going out to dinner with The Bank?”

Miss Beryl smiled, as she always did when Sully referred to Clive Jr. this way, and it occurred to her, not for the first time, that those who thought of stupid people as literal were dead wrong. Some of the least gifted of her eighth-graders had always had a gift for colorful metaphor. It was literal truth they couldn’t grasp, and so it was with Sully. He had been among the first students she’d ever taught in North Bath, and his IQ tests had revealed a host of aptitudes that the boy himself appeared bent on contradicting. Throughout his life a case study underachiever, Sully—people still remarked—was nobody’s fool, a phrase that Sully no doubt appreciated without ever sensing its literal application—that at sixty, he was divorced from his own wife, carrying on halfheartedly with another man’s, estranged from his son, devoid of self-knowledge, badly crippled and virtually unemployable—all of which he stubbornly confused with independence.