8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

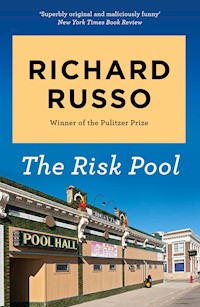

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In Mohawk, New York, Ned Hall is doing his best to grow up, even though neither of his estranged parents can properly be called adult. His father, Sam, cultivates bad habits so assiduously that he is stuck at the bottom of his car insurance risk pool. His mother, Jenny, is slowly going crazy from resentment at a husband who refuses either to stay or to stay away. As Ned veers between allegiances to these grossly inadequate role models, Richard Russo gives us a book that overflows with outsized characters and outlandish predicaments and whose vision of family is at once irreverent and unexpectedly moving.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

RICHARD RUSSO’STHE RISK POOL

“Russo’s writing is straightforward, hard-boiled realism—brisk and evocative.… The Risk Pool is a book whose simple truths live on, well after the final page is read.”

—Philadelphia Inquirer

“Power, passion and poignancy: In the story of a father and son, Rick Russo reminds me of James T. Farrell—a James T. Farrell who has not forgotten how to hope.”

—Andrew M. Greeley

“Russo’s realism is impeccable. His description of the depressed and restricted lives of Mohawk’s inhabitants is concrete and vivid.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Russo writes in a prose style as seductive as spring: the novel has a vigorous pace, sharply witty dialogue and a liberal helping of hilarious scenes. The book’s depiction of a community fallen on hard times, its vividly delineated characters, and its sensitive portrayal of a boy bewildered by the conditions of his life and learning to adapt to hardship, neglect and a curious kind of off-hand love all pack an emotional wallop. In short, it’s as good a novel as we are likely to get this year.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Russo writes with genuine passion and authority; his ear for dialogue is so acute that one can almost hear the characters speaking.”

—Chicago Tribune

“A great book. I fell in love with the characters in this novel as I once fell in love with the characters in Garp.”

—Pat Conroy

Richard Russo is the author of seven previous novels, two collections of stories, and On Helwig Street, a memoir. In 2002 he received the Pulitzer Prize for Empire Falls, which, like Nobody’s Fool, was adapted to film, in a multiple-award-winning HBO miniseries. He lives in Maine.

Titles by Richard Russo

Everybody’s Fool On Helwig Street That Old Cape Magic Bridge of Sighs The Whore’s Child Empire Falls Straight Man Nobody’s Fool The Risk Pool Mohawk

The Risk Pool

RICHARD RUSSO

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination and are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

First published in the United States of America in 1986 by Random House, Inc.

This edition published in Great Britain in 2017 by Allen & Unwin by arrangement with KERB Productions, Inc.

Copyright © Richard Russo, 1986

A portion of this book appeared in slightly different form in Granta (Granta #19, Fall 1986).

The moral right of Richard Russo to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin c/o Atlantic Books Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610 Fax: 020 7430 0916 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN 978 1 95253 556 7

For Jim Russo In Memoriam

Its inhabitants are, as the man once said, “whores, pimps, gamblers, and sons of bitches,” by which he meant Everybody. Had the man looked through another peephole he might have said, “Saints and angels and martyrs and holy men,” and he would have meant the same thing.

—John Steinbeck, Cannery Row

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges support from Southern Connecticut State University and Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, while he was working on this book. Special thanks also, for faith and assistance, to Nat Sobel, David Rosenthal, Gary Fisketjon, Greg Gottung, Jean Findlay and, always, my wife Barbara.

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Acknowledgments

Epilogue

About the Author

1

My father, unlike so many of the men he served with, knew just what he wanted to do when the war was over. He wanted to drink and whore and play the horses. “He’ll get tired of it,” my mother said confidently. She tried to keep up with him during those frantic months after the men came home, but she couldn’t, because nobody had been shooting at her for the last three years and when she woke up in the morning it wasn’t with a sense of surprise. For a while it was fun, the late nights, the dry martinis, the photo finishes at the track, but then she was suddenly pregnant with me and she decided it was time the war was over for real. Most everybody she knew was settling down, because you could only celebrate, even victory, so long. I don’t think it occurred to her that my father wasn’t celebrating victory and never had been. He was celebrating life. His. She could tag along if she felt like it, or not if she didn’t, whichever suited her. “He’ll get tired of it,” she told my grandfather, himself recently returned, worn and riddled with malaria, to the modest house in Mohawk he had purchased with a two-hundred-dollar down payment the year after the conclusion of the earlier war he’d been too young to legally enlist for. This second time around he felt no urge to celebrate victory or anything else. His wife had died when he was in the Pacific, but they had fallen out of love anyway, which was one of the reasons he’d enlisted at age forty-two for a war he had little desire to fight. But she had not been a bad woman, and the fact that he felt no loss at her passing depressed and disappointed him. From his hospital bed in New London, Connecticut, he read books and wrote his memoirs while the younger men, all malaria convalescents, played poker and waited for weekend passes from the ward. In their condition it took little enough to get good and drunk, and by early Saturday night most of them had the shakes so bad they had to huddle in the dark corners of cheap hotel rooms to await Monday morning and readmission to the hospital. But they’d lived through worse, or thought they had. My grandfather watched them systematically destroy any chance they had for recovery and so he understood my father. He may even have tried to explain things to his daughter when she told him of the trial separation that would last only until my father could get his priorities straight again, little suspecting he already did. “Trouble with you is,” my father told her, “you think you got the pussy market cornered.” Unfortunately, she took this observation to be merely a reflection of the fact that in her present swollen condition, she was not herself. Perhaps she couldn’t corner the market just then, but she’d cornered it once, and would again. And she must have figured too that when my father got a look at his son it would change him, change them both. Then the war would be over.

The night I was born my grandfather tracked him to a poker game in a dingy room above the Mohawk Grill. My father was holding a well-concealed two pair and waiting for the seventh card in a game of stud. The news that he was a father did not impress him particularly. The service revolver did. My grandfather was wheezing from the steep, narrow flight of stairs, at the top of which he stopped to catch his breath, hands on his knees. Then he took out the revolver and stuck the cold barrel in my father’s ear and said, “Stand up, you son of a bitch.” This from a man who’d gone two wars end to end without uttering a profanity. The men at the table could smell his malaria and they began to sweat.

“I’ll just have a peek at this last card,” my father said. “Then we’ll go.”

The dealer rifled cards around the table and everybody dropped lickety-split, including a man who had three deuces showing.

“Deal me out a couple a hands,” my father said, and got up slowly because he still had a gun in his ear.

At the hospital, my mother had me on her breast and she must have looked pretty, like the girl who’d cornered the pussy market before the war. “Well?” my father said, and when she turned me over, he grinned at my little stem and said, “What do you know?” It must have been a tender moment.

Not that it changed anything. Six months later my grandfather was dead, and the day after the funeral, for which my father arrived late and unshaven, my mother filed for divorce, thereby losing in a matter of days the two men in her life.

They may have departed my mother’s, but my father and grandfather remained the two pivotal figures in my own young life. Of the two, the grandfather I had no recollection of was the more vivid, thanks to my mother. By the time I was six I was full of lore concerning him, and now, at age thirty-five, I can still quote him chapter and verse. “There are four seasons in Mohawk,” he always remarked (in my mother’s voice). “Fourth of July, Mohawk Fair, Eat the Bird, and Winter.” No way around it, Mohawk winters did cling to our town tenaciously. Deep into spring, when tulips were blooming elsewhere, brown crusted snowbanks still rose high from the terraces along our streets, and although yellow water ran along the curbs, forming tunnels beneath the snow, the banks themselves shrank reluctantly, and it had been known to snow cruelly in May. It was late June before the ground was firm enough for baseball, and by Labor Day the sun had already lost its conviction when the Mohawk Fair opened. Then leper-white-skinned men, studies in congenital idiocy, hooked up the thick black snake-cables to a rattling generator that juiced The Tilt-A-Whirl, The Whip, and The Hammer. Down out of the hills they came, these white-skinned men with stubbled chins, to run the machines and leer at the taut blue faces of frightened children, leaning heavily and more heavily still on the metal bar that hurtled us faster and faster. When the garish colored lights of the midway, strung carelessly from one wooden pole to the next came down that first Tuesday morning in September, you could feel winter in the air. Fourth of July, Mohawk Fair, Eat the Bird, and Winter. I was an adult before I realized how cynical my grandfather’s observation was, his summer reduced to a single day; autumn to a third-rate mix of carnival rides, evil-smelling animals, mud and manure; Thanksgiving reduced to an obligatory carnivorous act, a “foul consumption,” he termed it; the rest Winter, capitalized. These became the seasons of my mother’s life after she realized the truth of my father’s observation about the pussy market. She worked for the telephone company and knew all about places with better seasons. At the end of the day she told me about the other operators she’d chatted with in places like Tucson, Arizona; and Albuquerque, New Mexico; and San Diego, California; where they capitalized the word Summer. “Someday …” she said, allowing her voice to trail off. “Someday.” Her inability to find a verb (or a subject, for that matter: I? We?) to give direction to her thought puzzled me then, but I’ve since concluded she didn’t truly believe in the existence of Tucson, Arizona, or perhaps didn’t believe that her personal seasons would be significantly altered by geographical considerations. She had inherited my grandfather’s modest house, and that rooted her to the spot. Its tiny mortgage payments were a blessing, because my mother was not overpaid by the telephone company. But the plumbing and electrical system were antiquated, and she was never able to get far enough ahead to do more than fix a pipe or individual wall socket. And of course the painters, roofers, electricians, and plumbers all saw her coming. So she subscribed to Arizona Highways and we stayed put.

Until I was six I thought of my father the way I thought of “my heavenly father,” whose existence was a matter of record, but who was, practically speaking, absent and therefore irrelevant. My mother had filed for divorce the day after my grandfather’s funeral, but she didn’t end up getting it. When he heard what she was up to, my father went to see her lawyer. He didn’t exactly have an appointment, but then he didn’t need one out in the parking lot where he strolled back and forth, his fists thrust deep into his pockets, his steaming breath visible in the cold, waiting until F. William Peterson, Attorney-At-Law, closed up. It was one of the bleak dead days between Christmas and New Year’s. I don’t think my mother specifically warned F. William there would be serious opposition to her design and that the opposition might conceivably be extralegal in nature. F. William Peterson had been selected by my mother precisely because he was not a Mohawk native and did not know my father. He had moved there just a few months before to join as a junior partner a firm which employed his law school roommate. I imagine he had already begun to doubt his decision to come to Mohawk even before meeting my father in the gray half-light of late afternoon. F. William Peterson was a soft man of some bulk, well dressed in a knee-length overcoat with a fur collar, when he finally appeared in the deserted parking lot at quarter to five. Never an athletic man, he was engaged in pulling on a fine new pair of gloves, a Christmas gift from Mrs. Peterson, while trying at the same time not to lose his footing on the ice. My father never wore gloves and was not wearing any that day. For warmth, he blew into his cupped hands, steam escaping from between his fingers, as he came toward F. William Peterson, who, intent on his footing and his new gloves, hadn’t what a fair-minded man would call much of a chance. Finding himself suddenly seated on the ice, warm blood salty on his lower lip, the attorney’s first conclusion must have been that somehow, despite his care, he had managed to lose his balance. Just as surprisingly, there was somebody standing over him who seemed to be making rather a point of not offering him a hand up. It wasn’t even a hand that dangled in F. William’s peripheral vision, but a fist. A clenched fist. And it struck the lawyer in the face a second time before he could account for its being there.

F. William Peterson was not a fighting man. Indeed, he had not been in the war, and had never offered physical violence to any human. He loathed physical violence in general, and this physical violence in particular. Every time he looked up to see where the fist was, it struck him again in the face, and after this happened several times, he considered it might be better to stop looking up. The snow and ice were pink beneath him, and so were his new gloves. He thought about what his wife, an Italian woman five years his senior and recently grown very large and fierce, would say when she saw them and concluded right then and there, as if it were his most pressing problem, that he would purchase an identical pair on the way home. Had he been able to see his own face, he’d have known that the gloves were not his most pressing problem.

“You do not represent Jenny Hall,” said the man standing in the big work boots with the metal eyelets and leather laces.

He did represent my mother though, and if my father thought that beating F. William Peterson up and leaving him in a snowbank would be the end of the matter he had an imperfect understanding of F. William Peterson and, perhaps, the greater part of the legal profession. My father was arrested half an hour later at the Mohawk Grill in the middle of a hamburg steak. F. William Peterson identified the work boots with the metal eyelets and leather laces, and my father’s right hand was showing the swollen effects of battering F. William Peterson’s skull. None of which was the sort of identification that was sure to hold up in court, and the lawyer knew it, but getting my father tossed in jail, however briefly, seemed like a good idea. When he was released, pending trial, my father was informed that a peace bond had been sworn against him and that if he, Sam Hall, was discovered in the immediate proximity of F. William Peterson, he would be fined five hundred dollars and incarcerated. The cop who told him all this was one of my father’s buddies and was very apologetic when my father wanted to know what the hell kind of free country he’d spent thirty-five months fighting for would allow such a law. It stank, the cop admitted, but if my father wanted F. William Peterson thrashed again, he’d have to get somebody else to do it. That was no major impediment, of course, but my father couldn’t be talked out of the premise that in a truly free country, he’d be allowed to do it himself.

So, instead of going to see F. William Peterson, he went to see my mother. She hadn’t sworn out any peace bond against him that he knew of. Probably she couldn’t, being his wife. It might not be perfect, but it was at least some kind of free country they were living in. Here again, however, F. William Peterson was a step ahead of him, having called my mother from his room at the old Nathan Littler Hospital, so she’d be on the lookout. When my father pulled up in front of the house, she called the cops without waiting for pleasantries, of which there turned out to be none anyway. They shouted at each other through the front door she wouldn’t unlock.

My mother started right out with the main point. “I don’t love you!” she screamed.

“So what?” my father countered. “I don’t love you either.”

Surprised or not, she did not miss a beat. “I want a divorce.”

“Then you can’t have one,” my father said.

“I don’t need your permission.”

“Like hell you don’t,” he said. “And you’ll need more than a candy-ass lawyer and a cheap lock to keep me out of my own house.” By way of punctuation, he put his shoulder into the door, which buckled but did not give.

“This is my father’s house, Sam Hall. You never had anything and you never will.”

“If you aren’t going to open that door,” he warned, “you’d better stand back out of the way.”

My mother did as she was told, but just then a police cruiser pulled up and my father vaulted the porch railing and headed off through the deep snow in back of the house. One of the cops gave chase while the other circled the block in the car, cutting off my father’s escape routes. It must have been quite a spectacle, the one cop chasing, until he was tuckered out, yelling, “We know who you are!” and my father shouting over his shoulder, “So what?” He knew nobody was going to shoot him for what he’d done (what had he done, now that he thought about it?). A man certainly had the right to enter his own house and shout at his own wife, which was exactly what she’d keep being until he decided to divorce her.

It must have looked like a game of tag. All the neighbors came out on their back porches and watched, cheering my father, who dodged and veered expertly beyond the outstretched arms of the pursuing cops, for within minutes, the backyards of our block were lousy with uniformed men who finally succeeded in forming a wide ring and then shrinking it, the neighbors’ boos at this unfair tactic ringing in their ears. My mother watched from the back porch as the tough, wet, angry cops closed in on my father. She pretty much decided right there against the divorce idea.

It dawned on her much later that the best way of ensuring my father’s absence was to demand he shoulder his share of the burden of raising his son. But until then, life was rich in our neighborhood. When he got out of jail, my father would make a beeline for my mother’s house (she’d had his things put in storage and changed the locks, which to her mind pretty much settled the matter of ownership), where he’d be arrested again for disturbing the peace. His visits to the Mohawk County jail got progressively longer, and so each time he got out he was madder than before. Finally, one of his buddies on the Mohawk P.D. took him aside and told him to stay the hell away from Third Avenue, because the judge was all through fooling around. Next time he was run in, he’d be in the slam a good long while. Since that was the way things stood, my father promised he’d be a good boy and go home, wherever that might be. Since one place was as good as another, he rented a room across from the police station so they’d know right where to find him. He borrowed some money and got a couple things out of storage and set them in the middle of the rented room. Then he went out again.

He started drinking around three in the afternoon and by dinnertime found a poker game, a good one, as luck would have it, with all good guys and no problems. Except that by ten my father had lost what he had on him and had to leave the game in search of a soft touch. That time of night, finding somebody with a spare hundred on him was no breeze, even though everybody knew Sam Hall was good for it. He hit a couple of likely spots, then started on the unlikely ones. He got some drinks bought for him, sort of consolation, by people who wouldn’t or couldn’t loan him serious cash. Midnight found him in the bar of The Elms, a classy restaurant on the outskirts of town, where he tried to put the touch on Jimmy Albanese, and who should walk in but F. William Peterson, and on his arm a good-looking young woman who happened not to be his wife, but was surely someone’s. The lawyer took her to a dark, corner booth and they disappeared into its shadows. When the cocktail waitress came back to the bar with their order, my father said he’d cover the round and would she tell his friends “Up the Irish.” When F. William Peterson looked over and saw my grinning father with his glass raised, the blood drained from his face. He recognized his former assailant from the diner, of course, and had in fact been on the lookout for him, especially in parking lots, though lately he had relaxed his vigilance somewhat after my mother informed him of her decision to drop divorce proceedings, a decision he went on record as opposing on general principle and because it meant he’d taken a horrible beating for nothing. Had she bothered to inform her husband that she had dropped the suit? the lawyer wondered. Probably not, or what the hell would Sam Hall be doing at The Elms? It would be just like her not to tell him, and now he’d have to think of a way to avoid another beating, this time in a public place. A public place he wasn’t supposed to be, in the company of a woman whose husband worked the night shift. The good news was that the bar was still pretty crowded, and he doubted Sam Hall would assault him until the place cleared out a little. He and the young woman could make a run for the parking lot, but he doubted they’d make it and he’d have to explain to the woman why they were running, and this was hardly the image of himself that he chose to cultivate. Probably the best thing, F. William Peterson concluded, would be to determine the man’s intentions and try to talk him out of them. So he got up, excused himself, and went over to where my father sat talking to Jimmy Albanese.

“You understand,” he said to my father, “that by sitting on that stool, you are violating the peace bond sworn against you, an offense for which you could be incarcerated?”

My father looked over at Jimmy Albanese, who happened to be the next best thing to a lawyer, having failed the New York bar exam on three separate occasions.

“He’s full of shit,” was the honorable Jimmy’s expert assessment. “You come in first. He’s harassing your ass.”

“I tell you what,” my father said. “You let me take a hundred right now, and I forget the whole thing. You get the hundred back on Wednesday. Friday the latest.”

It was a strange request, but F. William Peterson was tempted because he was very afraid of my father, who he was now convinced was certifiable. Unfortunately, he was a little short. “I can let you have fifty …”

My father frowned. “Fifty.”

The lawyer showed him his wallet, which contained fifty-seven dollars.

“All right,” my father said reluctantly, pocketing the money. It was better than nothing, and it was easier to touch somebody else for the other half a hundred. And besides, he’d just had an idea. “I guess that makes us even. Thanks.”

He was in a hurry, but there was a telephone booth outside The Elms and my father could feel that his luck was changing. Everything was beginning to have that falling-into-place feeling. Before driving to my mother’s, he called Mrs. F. William Peterson. Yes, she knew right where The Elms was located. And yes, if she hurried she supposed she could meet her husband there in fifteen minutes.

Now they were even.

By the time he got to Third Avenue it was late and the house was dark, but he managed to raise my mother. “Don’t call the cops,” he said urgently when he heard stirring inside.

My mother suspected a trick and raised the shade and window tentatively.

“Let me take fifty till tomorrow,” he said.

“What?”

“Fifty. I’ll pay you back tomorrow and after that I’ll stay clear of here.”

“Will you give me a divorce?”

“No,” he said. “But I won’t bother you anymore. That’s the deal.”

My mother knew him and knew she had him. “We have a son to raise,” she said. “I can’t do it alone. You’ll have to give me fifty a month.”

He thought about it. “Okay,” he said finally. “Sure.”

With matters settled thus satisfactorily out of court, my mother gave him the money and considered herself fortunate, which she was. She would never collect a dime of the informal, modest alimony settlement, but then she didn’t expect to. The important thing was that she’d gotten my father to agree to it in a moment of weakness, and he’d feel guilty about not keeping his word, and he’d stay a suitable distance rather than give her the opportunity to bring the matter up. After a year or so, the debt would be considerable and he would be alert to chance meetings on the street and, in effect, she would have her divorce. She slept soundly that night, knowing the burden she had placed on him. As it turned out, her strategy worked better than she could have hoped, because in the middle of June she ran into F. William Peterson, who informed her that Sam Hall had blown town. The lawyer also wanted to know if she’d like to go out with him sometime, what with Mrs. Peterson divorcing him and all.

Mohawk didn’t see my father again for nearly six years, and my mother never got over what you could buy with fifty dollars, invested wisely.

2

Even as a child, I never had much use for conventional honesty. I can’t remember my first lie, but I do recall the first one I was caught at. Many years later when I was at the university, I confessed it to a young woman I was infatuated with, and she used me for a case study in her psych class, in return for which I got to use her for nonacademic advantage. Here’s the story I told her. The true story, more or less, of my first imaginative untruth.

I was a first grader in McKinley Elementary School (kindergarten was optional and we hadn’t opted), and word had gotten around among the other children that my father did not live with my mother and me, an unusual circumstance in 1953 and one which made me the center of attention that September, the Mohawk Fair being over, and no real freaks (like the Heroin Monster: “See her, you’ll want to kill her!”) to gawk at for another year. My mother instructed me to say only that it was nobody’s business where my father lived, which suggests how little she understood children if she thought such a lame response would have any effect other than the inflaming of their natural, arrogant curiosity. Happily, I arrived at a more sensible solution to my problem. I informed everyone that my father was dead, and the beneficial effect of this intelligence I felt immediately. I couldn’t have been more pleased with myself.

One day, not long after I began telling this lie, however, my teacher, Miss Holiday, took me by the hand and led me outside while the other children, obediently curled up on mats, had been instructed to nap. There at the curb was a lone, dirty white convertible. Inside was a man, and when he leaned across the front seat to open the passenger-side door, my heart did something funny and I stopped right where I was, Miss Holiday pressing up against me from behind. The man in the car had a gray chin, and the fingers that first encircled the steering wheel, then came toward me to release the door lock, were black and calloused. A cigarette dangled carelessly from the man’s lips, and bobbed when he spoke. “Thanks, young lady,” my father said.

Miss Holiday wasn’t pressing against me anymore. Maybe she too was looking at his black fingers. “I don’t know about this,” she said. “I could lose my job.”

“Nah,” my father said, and perhaps his failure to elaborate why not was just the right thing, because she suddenly nudged me into the car and scurried back up the walk.

“Well?” said my father. I’ve often wondered whether he was as sure that I was his son as I was that he was my father. There was little enough physical resemblance at that stage. My hair was blond and curly, his wiry and black and bushy. Did he think that maybe the fool of a young woman had grabbed the wrong kid, or did he feel something when he saw me that said this is the one? “You know who I am?”

I nodded.

“Can you talk?”

I nodded again, feeling my eyes fill.

“Who am I?”

I couldn’t force anything out, couldn’t look at him, except for the black thumb and finger which pressed the life out of the burning cigarette and deposited the stub in the full ashtray.

“All right,” he said. “Who are you?”

“Ned,” I gulped.

“Ned Who?”

“Ned Hall.”

“Right. You know where the name Hall came from?”

I shook my head. He was lighting another cigarette, and when he had done it, he tossed the still burning match into an ashtray, the flame inching down the cardboard stem, leaving it as black as my father’s thumb and forefinger.

“Your mother tell you to say I was dead?”

I shook my head.

“Don’t lie to me.”

I began to cry, because I wasn’t lying.

“She’ll wish she hadn’t,” he said. “You can bet your ass.”

He sat and smoked and couldn’t think of anything else to ask me. “You want to go back to school or do you want some ice cream at the dairy?”

I reached for the door handle, which I couldn’t get to move. The black fingers came over and did it. By the time I got back inside, I was shaking so badly that Miss Holiday took me to see the nurse, who examined me, and finding a low-grade fever decided to drive me home. As we turned the corner onto my street, a white convertible fishtailed away from the curb and away up the hill, just as a police car appeared at the rise coming in the opposite direction. Several neighbors were out on their porches and pointed the way of the fleeing convertible, and the patrol car did a clumsy, two-stage U-turn.

“This means war,” my mother said when she finally got calmed down. Her eyes were glowing like the tip of my father’s cigarette.

War it was.

My mother was game, at least in the beginning. Every time he turned up—he averaged twice a week—she called the cops. For my father’s part, it was a guerrilla war, hit and run, in and out. His favorite time was three in the morning below my mother’s window, drunk often as not, and ready to kick up a hell of a fuss before vanishing into the night thirty seconds before the cops pulled up. He had a drunk’s radar where cops were concerned. One night during the second week of his marauding, a policeman was stationed around back after dark, so my father phoned instead of putting in a personal appearance. “How long is that fat cop planning to squat in the bushes back there?” he asked my mother. “You better draw your blinds, I know that son of a bitch.” In fact, he knew them all, and that was the problem. Every time a policeman was assigned to us, my father knew about it. Usually, he knew which one.

Nobody seemed able to find out where he was living, though rumor had it that he was working road construction down the line in Albany. His nocturnal visits continued all summer, and by the end of August my mother was done in. At first he just accused her of instructing me to tell everybody he was dead, but he had other gripes too. He’d had a good look at me in the car that day, and he didn’t like the way I was turning out. In his opinion she was turning me into a little pussy. And speaking of pussy, he heard she’d been seen around town.

This last accusation was beyond everything. In the six years he’d been gone, my mother might as well have been a nun. She could count the dates she’d had on one hand, she said. “That’s not the point,” he said. His long absence did not strike him as a mitigating circumstance, any more than did their mutual lack of tender feeling for each other. “You’re my wife,” he said. “And as long as you are, stay the hell home where you belong.”

As I look back on this period in our troubled lives, what astonishes me is how little the trouble touched me. My father’s nocturnal raids seldom woke me fully, and the next morning I was only vaguely aware that something had happened during the night. On such mornings my mother always questioned me about how I’d slept, and when I said fine, her expression was equal parts relief and astonishment that it was possible for anybody to sleep through what invariably woke the neighbors. Probably I willed myself to sleep through those episodes, too afraid to wake up. I remember that summer as a nervous time. I was always on the lookout for the white convertible and under explicit instructions to run inside and tell my mother if it appeared.

That year must have been a lonely one for my mother, who had to work all day at the phone company, then come home and endure the horror of being awakened in the middle of the night, sometimes out of sheer anticipation. She had no one to share her burdens with, your average six-year-old being an imperfect confidant. To make matters worse, she had scruples about the way she dealt with my father and even about the way she portrayed him to me. “No, he isn’t a bad man,” she responded to my surprise question one day. “He wouldn’t ever do anything to hurt you. He’s just careless. He wouldn’t look out for you the way I do.”

I thought about him a lot that winter, though the cold weather and deep snow discouraged him from beneath my mother’s bedroom window. The few minutes I’d spent with him in the dirty white convertible had somehow changed everything, not that I could have explained how or why. It was as if I suddenly understood intuitively nameless things I hadn’t missed before becoming aware of them. I kept seeing his black thumb and forefinger snuffing out the red cigarette tip, a gesture I practiced with candy cigarettes until my mother caught me at it and wanted to know what I was doing. I knew better than to explain.

It wasn’t that I loved him, of course. But when I thought about my father, my heart did that same funny thing it had done that afternoon he leaned across the front seat of the car and threw open the passenger-side door.

In the yard behind our house was a maple that had been planted by my grandfather before the war. It was a small boy’s dream. I lived to climb it. Its trunk was too thick to shinny up, but a makeshift ladder of two-by-four chunks had been nailed into it, and these brought the climber as far as the crotch, about six feet up, where the tree divided, unequally, the dwarf side rising about halfway up the house, the healthy dominant side to a much higher altitude.

I was forbidden to climb the tree after the day my mother came out onto the back porch, called my name, and my voice drifted down to her from second story level, at the very top of the tree’s dwarf side. I swung down from branch to branch to show off my dexterity. My mother wasn’t impressed. “If I ever catch you in that tree again …” she said. She either liked unfinished sentences or couldn’t think of how to finish them, and I resented her unwillingness to spell out consequences. It was impossible to weigh alternatives without them. But I was an obedient boy and did as I was told whenever she was around.

After school got out at 3:30, my mother’s cousin—Aunt Rose, I called her—looked after me until quarter of five when my mother got home from the phone company. Aunt Rose’s little house was around the corner and up the street from where we lived, halfway between my school and home. She fed me macaroons and we laughed immoderately at Popeye the Sailor. Aunt Rose also liked professional wrestling on Saturday afternoons, though her face got red with moral indignation at what some of the contestants got away with and how blind the referees were. Weekdays, after Olive Oyl was rescued, I headed home to await my mother on the front porch. Ours was probably the only house in Mohawk that was always locked. The only one that needed to be, my mother said. I knew why, though I wasn’t supposed to. It was to keep my father out.

The fifteen minutes between 4:30 and 4:45 was my time in the tree. Each day I dared a little higher, the slender upper branches bending beneath my seven-year-old weight. I was convinced that if I could make it to the top of the tree, I would be able to look out over the roof of my grandfather’s house, beyond Third Avenue, across all of Mohawk. I quickly mastered the dwarf side, but I was afraid to try the other. The branch I needed in order to begin was just beyond my reach, even when I stood on tiptoe in the crotch below. Although no great leap was necessary, my knees always got weak and I was afraid. If I failed to grab hold of the limb, I would fall all the way to the ground.

Day after day I stood sorrowfully in the crotch, staring into the center of the tree, immobile, full of self-hate and terrible yearning, until my mental clock informed me that my mother’s ride would deposit her on the terrace any minute. The ground felt soft as a pillow when I swung down, and I knew I was a coward.

One afternoon, as I stood there, gazing up into that dark green and speckled blue height, I was suddenly aware that I was being watched, and when I turned, he stood there on the back porch, leaning forward with his arms on the railing. I could tell he’d been there for some time, and I was even more ashamed than other days when there were no witnesses. I knew when I saw him standing there that I had never intended to jump.

“Well?” he said.

And that one word was all it took. I don’t remember jumping. Suddenly, I just had a hold of the limb with both hands, then had a knee over, then with a heave, I was up. The rest of the way would be easy, I knew, and I didn’t care about it. I could do it any day.

“You better come down,” my father said. “Your mother catches you up there, she’ll skin us both.”

Even as he spoke, we heard a car pull up out front. I swung down lickety-split.

“You figure you can keep a secret?” he said.

When I said sure, he nimbly vaulted the porch railing and landed next to me, so close we could have touched. Then he was gone.

3

A week later he kidnapped me.

I had left Aunt Rose’s and was on my way home when I saw the white convertible. It was coming toward me up the other side of the street, traveling fast. I didn’t think it would stop, but it did. At the last moment it swerved across the street to my side and came to a rocking halt, one wheel over the curb.

“What’s the matter?” my father wanted to know. I must have looked like something was the matter. He had a gray chin again and his hair looked crazy until he ran his black fingers through it, which helped only a little.

I said nothing was the matter.

“You want to go for a ride?”

I figured he must mean to the dairy for ice cream.

“Come here,” he said.

I started around the car to the passenger side.

“Here,” he repeated. “You know what ‘here’ means?”

Actually, I don’t think I did. At least I couldn’t figure out what good it would do me to walk over and stand next to him outside the car. I found out though, because suddenly he had me under the arms, and then I was high in the air, above the convertible’s windshield, where I rotated 180 degrees and plopped into the seat beside him. My teeth clicked audibly, but other than that it was a smooth landing.

He put the convertible in gear and we thumped down off the curb and up the street past Aunt Rose’s in the opposite direction from the dairy. I figured he’d turn around when we got to the intersection, but he didn’t. We just kept on going, straight out of Mohawk. My father’s hair was wild again, and mine was too, I could feel it.

The car smelled funny. My father didn’t seem aware of it until finally he sniffed and said, “Ah, shit,” and pulled over so that he was half on the road and half on the shoulder. First he flung up the hood, then the trunk. With the hood up, the funny burning smell was even worse. My father got two yellow cans out of the trunk and punched holes in them. Then he unscrewed a cap on the engine and poured in the contents of the two cans. In the gap between the dash and the hood I could see his black fingers working. I thought about my mother, who would be just about putting her key in the front door lock and wondering how come I wasn’t on the front porch to greet her. I started to send her a telepathic thought, “I’m with my father,” until I remembered that the message wouldn’t exactly comfort her should she receive it.

My father slammed the hood and trunk and got back in the car.

“Ever see one of these?” He dropped something small and heavy in my lap. A jackknife, it looked like. I knew my mother wouldn’t want me to touch it. “Open it,” my father said.

I did. Every time I opened something, there was something else to open. There were two knives, a large one and a small one, the can opener I’d seen him use, a pair of tiny scissors you could actually work, assuming you had something that tiny that needed scissoring, a thing you could use to clean your nails with and a file. There were other features too, but I didn’t know what they were for. With all its arms opened up, the gadget looked like a lopsided spider.

“Don’t lose it,” he said.

We were pretty well out in the country now and when he pulled into a long dirt driveway, I was sure he just meant to turn around. Instead, he followed the road on through a clump of trees to a small, rusty trailer. A big, dark-skinned man in a shapeless hat was seated on a broken concrete block. I was immediately interested in the hat, which was full of shiny metallic objects that reflected the sun. He stood when my father jerked the car to a stop, crushed stone rattling off the trailer.

“Well?” my father said.

The man consulted his watch. “Hour late,” he said. “Not bad for Sam Hall. Practically on time. Who’s this?”

“My son. We’ll teach him how to fish.”

“Who’ll teach you?” the man said. “Howdy, Sam’s Kid.”

He offered a big, dark-skinned hand.

“Go ahead and shake his ugly paw,” my father said.

I did, and then the man gathered up the gear that was resting up against the trailer. “You want to open this trunk, or should I just rip it off the hinges?” he said when my father made no move to get out and help.

“Kind of ornery, ain’t he,” my father said confidentially, tossing the keys over his shoulder.

“Hey, kid,” the man said. “How’d you like to ride in the back?”

“Tell him to kiss your ass,” my father advised. “You got enough gear for three?”

The man reluctantly got in the back. “Enough for me and the kid anyways. Don’t know about you. Can he talk or what?”

My father swatted me. “Say hello to Wussy. He’s half colored, half white, and all mixed up.”

Wussy leaned forward so he could see into the front seat. “He ain’t exactly dressed for this.” I was wearing a thin t-shirt, shorts, sneakers. “Course, you aren’t either. You planning to attend a dance in those shoes?”

“I didn’t have time to change,” my father shrugged.

“Where the hell were you?”

My father started to answer, then looked at me. “Someplace.”

“Oh,” the man called Wussy said. “I been there. Hey, Sam’s Kid, you know what a straight flush is?”

I shook my head.

“His name is Ned.”

“Ned?”

My father nodded. “I wasn’t consulted.”

“How come?”

“I wasn’t around might have had something to do with it.”

“Where were you?”

“Someplace,” my father said. “Which reminds me.”

We were speeding along out in the country and there was a small store up ahead. We pulled in next to the telephone booth. My father closed the door behind him, but I could still hear part of the conversation. My father said she could kiss his ass.

When he got back in the car, my father looked at me and shook his head as if he thought maybe I’d done something. “Don’t lose that,” he said. I was still fingering the spider gadget.

“As long as we’re stopped,” Wussy said, “what do you say we put the top up?”

“What for?” my father said.

Wussy tapped me on the shoulder and pointed up. The sun had disappeared behind dark clouds, and the air had gone cool.

“Your ass,” my father said, jerking the car back onto the highway.

Ten minutes later the skies opened.

“Your old man is a rockhead,” Wussy observed after they finally got the top up. It had stuck at first and we were all soaked. “No wonder your mother don’t want nothing to do with him.”

It was nearly dark when we got to the cabin. We had to leave the convertible at the end of the dirt road and hike in the last mile, the sun winking at us low in the trees. We followed the river, more or less, though there were times when it veered off to the left and disappeared. Then after a while we would hear it again and there it would be. Wussy—it turned out that his name was Norm—led the way, carrying the rods and most of the tackle, then me, then my father, complaining every step. His black dress shoes got ruined right off, which pleased Wussy, and the mosquitoes ate us. My father wanted to know who would build a cabin way the hell and gone off in the woods. It seemed to him that anybody crazy enough to go to all that trouble might better have gone to a little more and poured a sidewalk, at least, so you could get to it. Wussy didn’t say anything, but every now and then he’d hold on to a wet branch and then let go so that it whistled over the top of my head and caught my father in the chin with a thwap, after which Wussy would say, “Careful.”

I was all right for a while, but then the woods began to get dark and I felt tired and scared. When something we disturbed scurried off underfoot and into the bushes, I got to thinking about home and my tree and my mother, who had no idea where I was. It occurred to me that if I let myself get lost, nobody would ever find me, and the more I thought about it, the closer I stuck to Wussy, ready to duck whenever he sent a branch whistling over my head.

“I hope you didn’t bring me all the way out here to roll me, Wuss,” my father said. “I should have mentioned I don’t have any money.”

“I want those shiny black shoes.”

“You would, you black bastard.”

“Nice talk, in front of the kid.” A branch caught my father in the chops.

“What color is he, bud?” my father poked me in the back.

I was embarrassed. My mother had told me about Negroes and that it wasn’t nice to accuse them of it. Wussy’s skin was the color of coffee, at least the way my mother drank it, with cream and sugar. “I don’t know,” I said.

“That’s all right,” my father said. “He’s none too sure either.”

And then suddenly we were out of the trees and there was the cabin, the river gurgling about forty yards down the slope.

Wussy tossed all the gear inside and started a fire in a circle of rocks a few feet from the ramshackle porch. When it got going good, he brought out a big iron grate to put over it. With the sun down, it had gotten cool and the fire felt good. My father fidgeted nearby until Wussy told him he could collect some dry sticks if he felt like it. “You could have brought a pair of long pants and a jacket for him at least,” he said.

“Didn’t have a chance,” my father said.

“Look at him,” Wussy said critically. “Knees all scraped up …”

“How the hell did I know we were going to blaze a trail?” my father said. “You cold?”

“No,” I lied.

Wussy snorted. “I think I saw blankets inside.”

My father went to fetch them. “Your old man’s a rockhead,” Wussy observed again. “Otherwise, he’s all right.”

He didn’t seem to need me to agree, so I didn’t say anything. He opened three cans of chili with beans into a black skillet and set it on top of the grate. Then he chopped up two yellow onions and added them. You couldn’t see much except the dark woods and the outline of the cabin. We heard my father banging into things and cursing inside. After a few minutes the chili began to form craters which swelled, then exploded. “Man-color,” Wussy said. “That’s what I am.”

My father finally came back with a couple rough blankets. He draped one over me and threw the other around his own shoulders.

“No thanks,” Wussy said. “I don’t need one.”

“Good,” my father said.

“And you don’t need any of this chili,” Wussy said, winking at me. “Me and you will have to eat it all, Sam’s Kid.”

My father squatted down and inspected the sputtering chili. “I hate like hell to tell you what it looks like.”

It looked all right to me and it smelled better than I knew food could smell. It was way past my normal dinner time and I was hungry. Wussy ladled a good big portion onto a plate and handed it to me. Then he loaded about twice as much onto a plate for himself.

“What the hell,” my father said.

“What the hell is right,” Wussy said. “What the hell, eh Sam’s Kid?”

My father got up and went back into the cabin for another blanket. When he returned, Wussy said no thanks, he was doing fine, but didn’t my father want any chili? “You better get going,” he advised. “Me and the kid are ready for seconds.”

We weren’t, exactly, but when he finished giving my father a pretty small portion, he ladled more onto my plate and the rest of the skillet onto his own.

“I bet there’s a lot of shallow graves out here in the woods,” my father speculated, pretending not to notice there was no more chili whether he hurried up or not. “You suppose anybody would miss you if you didn’t come home tomorrow?”

“Women, mostly,” Wussy said. “I feel pretty safe though. Mostly I worry about you. Anything happened to me, you’d starve before you ever located that worthless oil guzzler of yours.”

“Your ass.”

When I couldn’t eat any more, I gave the rest of my chili to my father, who looked like he was thinking of licking the hot skillet. “The kid’s all right,” Wussy said. “I don’t care who his old man is.”

It was so black out now that we couldn’t even see the cabin, just a thousand stars and each other’s faces in the dying fire.

Wussy blew the loudest fart I’d ever heard. “What color’s my skin?” he said, as if he hadn’t done anything at all.

I had been almost asleep, until the fart. “Man-color,” I said, wide awake again.

“There you go,” he said.

I woke with the sun in my eyes next morning. There were no curtains on the cabin’s high windows. I was still dressed from the night before. My legs, all scratched from the long walk through the woods, felt heavy and a little unsteady when I stood up. I looked around for a bathroom, but there wasn’t any.

My father and his friend Wussy were face down on the other two bunks. My father’s arms were coffee-colored, like Wussy’s, but his legs and back were fish-white. Wussy had taken the trouble to crawl under the covers, but my father lay on top. The cabin had been warm the night before, but it was chilly now, though my father didn’t seem aware of it. I was cold, and it made me really wish there was a bathroom. In the center of the small table was an empty bottle and a deck of cards fanned face up. They’d kept score in long uneven columns labeled N and S on a brown paper bag. The S columns were the longer ones, and the number 85 was circled at the top of the bag with a dollar sign in front of it. I had awakened several times during the night when one of them yelled “Gin!” or “You son of a bitch!” but I was too exhausted to stay awake. I watched the two sleepers for a while, but neither man stirred, so I went outside.

The iron skillet, alive with bright green flies, still sat on the grate. There were so many flies, and they were so furious that their bodies pinged against the metal like small pebbles. They would buzz frantically in the hardened chili for a few seconds, then do wide arcs above the skillet before diving back again. I watched with interest for a while and then went down to the river. We were so far upstream that it wasn’t very deep in most spots, a river in name only. Rocks jutted up above the surface of the water and it looked like you’d be able to jump from one to the next all the way to the opposite bank. I tried it, but only got partway, because when you got out toward the middle, the rocks weren’t as close together as they’d looked from the bank. One solid-looking flat rock tipped under my weight and I had to plunge one sneakered foot deep into the cool current to keep from falling in. The water ran so fast that the shoe was nearly sucked off, and I was scared enough to head back to shore on a squishy sneaker, aware that if my mother had been there, she’d have thrown a fit about my getting it wet. I doubted my father and Wussy would even notice. I found a comfortable rock on the bank and had another look at my father’s knife gadget, trying to pretend I didn’t have to go to the bathroom. Having the river right there made the necessity to pee hard to ignore. I wasn’t sure I could hold it all day.

After a while the door of the cabin opened and Wussy appeared in his undershorts. “Hello, Sam’s Kid,” he said. He tiptoed over to the spot where he’d built the fire, yanked himself out of his shorts and watered the bushes for a very long time. I could hear him above the sound of the river.

When he saw me watching, he said, “Gotta go, Sam’s Kid?”

I shook my head. I could hold out a while longer, and I wanted it to seem like my own idea when I went. I was very relieved to learn that peeing in the weeds was permissible, though it was one more thing I didn’t think I’d mention to my mother.

“First thing every morning for me,” Wussy explained. “Can’t wait.”