8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

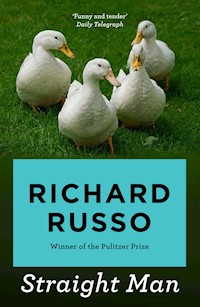

**THE BASIS FOR THE NEW TV SERIES, LUCKY HANK** Hank Devereaux is the reluctant chairman of the English department of a badly underfunded college in the Pennsylvania rust belt. Devereaux's reluctance is partly rooted in his character - he is a born anarchist - and partly in the fact that his department is savagely divided. In the course of a single week, Devereaux will have his nose mangled by an angry colleague, imagine his wife is having an affair with his dean, wonder if a curvaceous adjunct is trying to seduce him with peach pits and threaten to execute a goose on local television. All this while coming to terms with his philandering father, the dereliction of his youthful promise and the ominous failure of certain vital body functions. In short, Straight Man is classic Russo - side-splitting, poignant, compassionate and unforgettable.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

ACCLAIM FORRichard Russo’sSTRAIGHT MAN

“By turns hilarious and compassionate.”

—Chicago Tribune

“Russo can penetrate to the tender quick of ordinary American lives.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“A rich, complex novel … with sharp language and sharper imagination, [Russo] delivers the most engaging and rewarding cast of characters of any novel in recent memory.”

—Time Out

“One of our most adept surveyors of the human landscape.”

—Philadelphia Inquirer

“A delight.… [Straight Man has] a kind of buoyant sarcasm.”

—Dallas Morning News

“[Russo] surrounds the tragic awakening of small-town characters with humor while still preserving their poignancy.”

—Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel

“The humor prompts big belly laughs, and the pathos sets tears to flowing.”

—Houston Chronicle

“Russo has established himself as a thoughtful, ironic, and gifted comic novelist. With Straight Man, he confirms his place as one of the few modern satirists who not only shows the foibles of his characters, but also demonstrates their compassion, humility, and sense of humor.”

—Orlando Sentinel

Richard Russo is the author of seven previous novels, two collections of stories, and On Helwig Street, a memoir. In 2002 he received the Pulitzer Prize for Empire Falls, which, like Nobody’s Fool, was adapted to film, in a multiple-award-winning HBO miniseries. He lives in Maine.

Titles by Richard Russo

Everybody’s Fool On Helwig Street That Old Cape Magic Bridge of Sighs The Whore’s Child Empire Falls Straight Man Nobody’s Fool The Risk Pool Mohawk

Straight Man

RICHARD RUSSO

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination and are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

First published in the United States of America in 1997 by Random House, Inc.

This edition published in Great Britain in 2017 by Allen & Unwin by arrangement with KERB Productions, Inc.

Copyright © Richard Russo, 1997

The prologue to Straight Man was originally published, in slightly different form, as ‘Dog,’ in the December 23–30, 1996, issue of The New Yorker.

The moral right of Richard Russo to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin c/o Atlantic Books Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610 Fax: 020 7430 0916 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN 978 1 95253 557 4

For Nat and Judith

Special thanks for faith and hard work and good advice to David Rosenthal, Alison Samuel, and Barbara Russo, for technical assistance and/or inspiration to Jean Findlay, Ed Ervin, Toni Katz, Greg and Peggy Johnson, Kjell Meling, and Chris Cokinis.

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Titles by Richard Russo

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Epilogue

Also by Richard Russo

PROLOGUE

They’re nice to have. A dog.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald,The Great Gatsby

Truth be told, I’m not an easy man. I can be an entertaining one, though it’s been my experience that most people don’t want to be entertained. They want to be comforted. And, of course, my idea of entertaining might not be yours. I’m in complete agreement with all those people who say, regarding movies, “I just want to be entertained.” This populist position is much derided by my academic colleagues as simpleminded and unsophisticated, evidence of questionable analytical and critical acuity. But I agree with the premise, and I too just want to be entertained. That I am almost never entertained by what entertains other people who just want to be entertained doesn’t make us philosophically incompatible. It just means we shouldn’t go to movies together.

The kind of man I am, according to those who know me best, is exasperating. According to my parents, I was an exasperating child as well. They divorced when I was in junior high school, and they agree on little except that I was an impossible child. The story they tell of young William Henry Devereaux, Jr., and his first dog is eerily similar in its facts, its conclusions, even the style of its telling, no matter which of them is telling it. Here’s the story they tell.

I was nine, and the house we were living in, which belonged to the university, was my fourth. My parents were academic nomads, my father, then and now, an academic opportunist, always in the vanguard of whatever was trendy and chic in literary criticism. This was the fifties, and for him, New Criticism was already old. In early middle age he was already a full professor with several published books, all of them “hot,” the subject of intense debate at English department cocktail parties. The academic position he favored was the “distinguished visiting professor” variety, usually created for him, duration of visit a year or two at most, perhaps because it’s hard to remain distinguished among people who know you. Usually his teaching responsibilities were light, a course or two a year. Otherwise, he was expected to read and think and write and publish and acknowledge in the preface of his next book the generosity of the institution that provided him the academic good life. My mother, also an English professor, was hired as part of the package deal, to teach a full load and thereby help balance the books.

The houses we lived in were elegant, old, high-ceilinged, drafty, either on or close to campus. They had hardwood floors and smoky fireplaces with fires in them only when my father held court, which he did either on Friday afternoons, our large rooms filling up with obsequious junior faculty and nervous grad students, or Saturday evenings, when my mother gave dinner parties for the chair of the department, or the dean, or a visiting poet. In all situations I was the only child, and I must have been a lonely one, because what I wanted more than anything in the world was a dog.

Predictably, my parents did not. Probably the terms of living in these university houses were specific regarding pets. By the time I was nine I’d been lobbying hard for a dog for a year or two. My father and mother were hoping I would outgrow this longing, given enough time. I could see this hope in their eyes and it steeled my resolve, intensified my desire. What did I want for Christmas? A dog. What did I want for my birthday? A dog. What did I want on my ham sandwich? A dog. It was a deeply satisfying look of pure exasperation they shared at such moments, and if I couldn’t have a dog, this was the next best thing.

Life continued in this fashion until finally my mother made a mistake, a doozy of a blunder born of emotional exhaustion and despair. She, far more than my father, would have preferred a happy child. One spring day after I’d been badgering her pretty relentlessly she sat me down and said, “You know, a dog is something you earn.” My father heard this, got up, and left the room, grim acknowledgment that my mother had just conceded the war. Her idea was to make the dog conditional. The conditions to be imposed would be numerous and severe, and I would be incapable of fulfilling them, so when I didn’t get the dog it’d be my own fault. This was her logic, and the fact that she thought such a plan might work illustrates that some people should never be parents and that she was one of them.

I immediately put into practice a plan of my own to wear my mother down. Unlike hers, my plan was simple and flawless. Mornings I woke up talking about dogs and nights I fell asleep talking about them. When my mother and father changed the subject, I changed it back. “Speaking of dogs,” I would say, a forkful of my mother’s roast poised at my lips, and I’d be off again. Maybe no one had been speaking of dogs, but never mind, we were speaking of them now. At the library I checked out a half dozen books on dogs every two weeks and left them lying open around the house. I pointed out dogs we passed on the street, dogs on television, dogs in the magazines my mother subscribed to. I discussed the relative merits of various breeds at every meal. My father seldom listened to anything I said, but I began to see signs that the underpinnings of my mother’s personality were beginning to corrode in the salt water of my tidal persistence, and when I judged that she was nigh to complete collapse, I took every penny of the allowance money I’d been saving and spent it on a dazzling, bejeweled dog collar and leash set at the overpriced pet store around the corner.

During this period when we were constantly “speaking of dogs,” I was not a model boy. I was supposed to be “earning a dog,” and I was constantly checking with my mother to see how I was doing, just how much of a dog I’d earned, but I doubt my behavior had changed a jot. I wasn’t really a bad boy. Just a noisy, busy, constantly needy boy. Mr. In and Out, my mother called me, because I was in and out of rooms, in and out of doors, in and out of the refrigerator. “Henry,” my mother would plead with me. “Light somewhere.” One of the things I often needed was information, and I constantly interrupted my mother’s reading and paper grading to get it. My father, partly to avoid having to answer my questions, spent most of his time in his book-lined office on campus, joining my mother and me only at mealtimes, so that we could speak of dogs as a family. Then he was gone again, blissfully unaware, I thought at the time, that my mother continued to glare homicidally, for long minutes after his departure, at the chair he’d so recently occupied. But he claimed to be close to finishing the book he was working on, and this was a powerful excuse to offer a woman with as much abstract respect for books and learning as my mother possessed.

Gradually, she came to understand that she was fighting a battle she couldn’t win and that she was fighting it alone. I now know that this was part of a larger cluster of bitter marital realizations, but at the time I sniffed nothing in the air but victory. In late August, during what people refer to as “the dog days,” when she made one last, weak condition, final evidence that I had earned a dog, I relented and truly tried to reform my behavior. It was literally the least I could do.

What my mother wanted of me was to stop slamming the screen door. The house we were living in, it must be said, was an acoustic marvel akin to the Whispering Gallery in St. Paul’s, where muted voices travel across a great open space and arrive, clear and intact, at the other side of the great dome. In our house the screen door swung shut on a tight spring, the straight wooden edge of the door encountering the doorframe like a gunshot played through a guitar amplifier set on stun, the crack transmitting perfectly, with equal force and clarity, to every room in the house, upstairs and down. That summer I was in and out that door dozens of times a day, and my mother said it was like living in a shooting gallery. It made her wish the door wasn’t shooting blanks. If I could just remember not to slam the door, then she’d see about a dog. Soon.

I did better, remembering about half the time not to let the door slam. When I forgot, I came back in to apologize, sometimes forgetting then too. Still, that I was trying, together with the fact that I carried the expensive dog collar and leash with me everywhere I went, apparently moved my mother, because at the end of that first week of diminished door slamming, my father went somewhere on Saturday morning, refusing to reveal where, and so of course I knew. “What kind?” I pleaded with my mother when he was gone. But she claimed not to know. “Your father’s doing this,” she said, and I thought I saw a trace of misgiving in her expression.

When he returned, I saw why. He’d put it in the backseat, and when my father pulled the car in and parked along the side of the house, I saw from the kitchen window its chin resting on the back of the rear seat. I think it saw me too, but if so it did not react. Neither did it seem to notice that the car had stopped, that my father had gotten out and was holding the front seat forward. He had to reach in, take the dog by the collar, and pull.

As the animal unfolded its long legs and stepped tentatively, arthritically, out of the car, I saw that I had been both betrayed and outsmarted. In all the time we had been “speaking of dogs,” what I’d been seeing in my mind’s eye was puppies. Collie puppies, beagle puppies, Lab puppies, shepherd puppies, but none of that had been inked anywhere, I now realized. If not a puppy, a young dog. A rascal, full of spirit and possibility, a dog with new tricks to learn. This dog was barely ambulatory. It stood, head down, as if ashamed at something done long ago in its puppydom, and I thought I detected a shiver run through its frame when my father closed the car door behind it.

The animal was, I suppose, what might have been called a handsome dog. A purebred, rust-colored Irish setter, meticulously groomed, wonderfully mannered, the kind of dog you could safely bring into a house owned by the university, the sort of dog that wouldn’t really violate the no pets clause, the kind of dog, I saw clearly, you’d get if you really didn’t want a dog or to be bothered with a dog. It’d belonged, I later learned, to a professor emeritus of the university who’d been put into a nursing home earlier in the week, leaving the animal an orphan. It was like a painting of a dog, or a dog you’d hire to pose for a portrait, a dog you could be sure wouldn’t move.

Both my father and the animal came into the kitchen reluctantly, my father closing the screen door behind them with great care. I like to think that on the way home he’d suffered a misgiving, though I could tell that it was his intention to play the hand out boldly. My mother, who’d taken in my devastation at a glance, studied me for a moment and then my father.

“What?” he said.

My mother just shook her head.

My father looked at me, then back at her. A violent shiver palsied the dog’s limbs. The animal seemed to want to lie down on the cool linoleum, but to have forgotten how. It offered a deep sigh that seemed to speak for all of us.

“He’s a good dog,” my father said, rather pointedly, to my mother. “A little high-strung, but that’s the way with purebred setters. They’re all nervous.”

This was not the sort of thing my father knew. Clearly he was repeating the explanation he’d just been given when he picked up the dog.

“What’s his name?” my mother said, apparently for something to say.

My father had neglected to ask. He checked the dog’s collar for clues.

“Lord,” my mother said. “Lord, lord.”

“It’s not like we can’t name him ourselves,” my father said, irritated now. “I think it’s something we can manage, don’t you?”

“You could name him after a passé school of literary criticism,” my mother suggested.

“It’s a she,” I said, because it was.

It seemed to cheer my father, at least a little, that I’d allowed myself to be drawn into the conversation. “What do you say, Henry?” he wanted to know. “What’ll we name him?”

This second faulty pronoun reference was too much for me. “I want to go out and play now,” I said, and I bolted for the screen door before an objection could be registered. It slammed behind me, hard, its gunshot report even louder than usual. As I cleared the steps in a single leap, I thought I heard a thud back in the kitchen, a dull, muffled echo of the door, and then I heard my father say, “What the hell?” I went back up the steps, cautiously now, meaning to apologize for the door. Through the screen I could see my mother and father standing together in the middle of the kitchen, looking down at the dog, which seemed to be napping. My father nudged a haunch with the toe of his cordovan loafer.

He dug the grave in the backyard with a shovel borrowed from a neighbor. My father had soft hands and they blistered easily. I offered to help, but he just looked at me. When he was standing, midthigh, in the hole he’d dug, he shook his head one last time in disbelief. “Dead,” he said. “Before we could even name him.”

I knew better than to correct the pronoun again, so I just stood there thinking about what he’d said while he climbed out of the hole and went over to the back porch to collect the dog where it lay under an old sheet. I could tell by the careful way he tucked that sheet under the animal that he didn’t want to touch anything dead, even newly dead. He lowered the dog into the hole by means of the sheet, but he had to drop it the last foot or so. When the animal thudded on the earth and lay still, my father looked over at me and shook his head. Then he picked up the shovel and leaned on it before he started filling in the hole. He seemed to be waiting for me to say something, so I said, “Red.”

My father’s eyes narrowed, as if I’d spoken in a foreign tongue. “What?” he said.

“We’ll name her Red,” I explained.

In the years after he left us, my father became even more famous. He is sometimes credited, if credit is the word, with being the Father of American Literary Theory. In addition to his many books of scholarship, he’s also written a literary memoir that was short-listed for a major award and that offers insight into the personalities of several major literary figures of the twentieth century, now deceased. His photograph often graces the pages of the literary reviews. He went through a phase where he wore crewneck sweaters and gold chains beneath his tweed coat, but now he’s mostly photographed in an oxford button-down shirt, tie, and jacket, in his book-lined office at the university. But to me, his son, William Henry Devereaux, Sr., is most real standing in his ruined cordovan loafers, leaning on the handle of a borrowed shovel, examining his dirty, blistered hands, and receiving my suggestion of what to name a dead dog. I suspect that digging our dog’s grave was one of relatively few experiences of his life (excepting carnal ones) that did not originate on the printed page. And when I suggested we name the dead dog Red, he looked at me as if I myself had just stepped from the pages of a book he’d started to read years ago and then put down when something else caught his interest. “What?” he said, letting go of the shovel, so that its handle hit the earth between my feet. “What?”

It’s not an easy time for any parent, this moment when the realization dawns that you’ve given birth to something that will never see things the way you do, despite the fact that it is your living legacy, that it bears your name.

Part OneOCCAM’S RAZOR

What I expected, was Thunder, fighting Long struggles with men And climbing.

—Stephen Spender

CHAPTER1

When my nose finally stops bleeding and I’ve disposed of the bloody paper towels, Teddy Barnes insists on driving me home in his ancient Honda Civic, a car that refuses to die and that Teddy, cheap as he is, refuses to trade in. June, his wife, whose sense of self-worth is not easily tilted, drives a new Saab. “That seat goes back,” Teddy says, observing that my knees are practically under my chin.

When we stop at an intersection for oncoming traffic, I run my fingers along the side of the seat, looking for the release. “It does, huh?”

“It’s supposed to,” he says, sounding academic, helpless.

I know it’s supposed to, but I give up trying to make it, preferring the illusion of suffering. I’m not a guilt provoker by nature, but I can play that role. I release a theatrical sigh intended to convey that this is nonsense, that my long legs could be stretched out comfortably beneath the wheel of my own Lincoln, a car as ancient as Teddy’s Civic, but built on a scale more suitable to the long-legged William Henry Devereauxs of the world, two of whom, my father and me, remain above ground.

Teddy is an insanely cautious driver, unwilling to goose his little Civic into a left turn in front of oncoming traffic. “The cars are spaced just wrong. I can’t help it,” he explains when he sees me grinning at him. Teddy’s my age, forty-nine, and though his features are more boyish, he too is beginning to show signs of age. Never robust, his chest seems to have become more concave, which emphasizes his small paunch. His hands are delicate, almost feminine, hairless. His skinny legs appear lost in his trousers. It occurs to me as I study him that Teddy would have a hard time starting over—that is, learning how unfamiliar things work, competing, finding a mate. The business of young men. “Why would I have to start over?” he wants to know, a frightened expression deepening the lines around the corners of his eyes.

Apparently, to judge from the way he’s looking at me now, I have spoken my thought out loud, though I wasn’t aware of doing so. “Don’t you ever wish you could?”

“Could what?” he says, his attention diverted. Having spied a break in the oncoming traffic, he takes his foot off the brake and leans forward, his foot poised over but not touching the gas pedal, only to conclude that the gap between the cars isn’t as big as he thought, settling back into his seat with a frustrated sigh.

Something about this gesture causes me to wonder if a rumor I’ve been hearing about Teddy’s wife, June—that she’s involved with a junior faculty member in our department—just might be true. I haven’t given it much credence until now because Teddy and June have such a perfect symbiotic relationship. In the English department they are known as Fred and Ginger for the grace with which they move together, without a hint of passion, toward a single, shared destination. In an atmosphere of distrust and suspicion and retribution, two people working together represent a power base, and no one has understood this sad academic truth better than Teddy and June. It’s hard to imagine either of them risking it. On the other hand, it must be hard to be married to a man like Teddy, who’s always leaning forward in anticipation, foot poised above the gas pedal, but too cautious to stomp.

We are on Church Street, which parallels the railyard that divides the city of Railton into two dingy, equally unattractive halves. This is the broadest section of the yard, some twenty sets of tracks wide, and most of those tracks are occupied by a rusty boxcar or two. A century ago the entire yard would have been full, the city of Railton itself thriving, its citizens looking forward to a secure future. No longer. On Church Street, where we remain idling in the left-turn lane, there is no longer a single church, though there were once, I’m told, half a dozen. The last of them, a decrepit red brick affair, long condemned and boarded up, was razed last year after some kids broke in and fell through the floor. The large parcel of land it perched on now sits empty. It’s the fact that there are so many empty, littered spaces in Railton, like the windblown expanses between the boxcars in the railyard, that challenges hope. Within sight of where we sit waiting to turn onto Pleasant Street, a man named William Cherry, a lifelong Conrail employee, has recently taken his life by lying down on the track in the middle of the night. At first the speculation was that he was one of the men laid off the previous week, but the opposite turned out to be true. He had in fact just retired with his pension and full benefits. On television his less fortunate neighbors couldn’t understand it. He had it made, they said.

When it’s safe, when all the oncoming traffic has passed, Teddy turns onto Pleasant, the most unpleasant of Railton streets. Lined on both sides with shabby one- and two-story office fronts, Pleasant Street is too steep to climb in winter when there’s snow. Now, in early April, I suspect it may be too steep for Teddy’s Civic, which is whirring heroically in its lower gears and going all of fifteen miles an hour. There’s a plateau and a traffic light halfway up, and when we stop, I say, “Should I get out and push?”

“It’s just cold,” Teddy tells me. “Really. We’re fine.”

No doubt he’s right. We will make it. Why this fact should be so discouraging is what I’d like to know. I can’t help wondering if William Cherry also feared things would work out if he didn’t do something drastic to prevent them.

“I think I can, I think I can, I think I can,” I chant, as the light changes and Teddy urges forward the Little Civic That Could. A few months ago I foolishly tried to climb this same hill in a light snow. It was nearly midnight, and I was heading home from the campus and hadn’t wanted to go the long way, which added ten minutes. During the long Pennsylvania winters, curbside parking is not allowed at night, so the street had a deserted, ominous feel. Mine was the only car on the five-block incline, and I made it without incident to this very plateau where Teddy and I have now stopped. The office of my insurance agent was on the corner, and I remember wishing he was there to see me do something so reckless in a car he was insuring. When the light changed, my tires spun, then caught, and I labored up the last two blocks. I couldn’t have been more than ten yards from the crest of the hill when I felt the tires begin to spin and the rear end to drift. When the car stalled and I realized the brake exerted no meaningful influence, I sat back and became a witness to my own folly. With the engine dead and the snow muffling all other sounds, I found myself in a silent ballet as I slalomed gracefully down the hill, backward as far as the landing where it appeared that I would stop, right in front of my insurance agent’s, but then I slipped over the edge and spun down the last three blocks, rebounding off curbs like the cue ball in a game of bumper pool, finally coming to rest at the entrance to the railyard, having suffered a loss of equilibrium but otherwise unscathed. A friend, Bodie Pie, who lives in a second-floor flat near the bottom of the hill and claims to have witnessed my balletic descent, swears she heard me laughing maniacally, but I don’t remember that. The only emotion I recall is similar to the one I feel now, with Teddy on this same hill. That is, a certain sense of disappointment about such drama resulting in so little consequence. Teddy is sure we’ll make it, and so am I. We have tenure, the two of us.

Once out of town, the rejuvenated Civic rushes along the two-lane blacktop like a cartoon car with a big, loopy smile (I knew I could, I knew I could), the Pennsylvania countryside hurtling by. Most of the trees along the side of the road are budding. Farther back in the deep woods there may still be patches of dirty snow, but spring is definitely in the air, and Teddy has cracked his window to take advantage of it. His thinning hair stirs in the breeze, and I half-expect to see evidence of new leafy growth on his scalp. I know he’s been contemplating Rogaine. “You’re only taking me home so you can flirt with Lily,” I tell him.

This makes Teddy flush. He’s had an innocent crush on my wife for over twenty years. If there’s such a thing as an innocent crush. If there’s such a thing as innocence. Since we built the house in the country, Teddy’s had fewer opportunities to see Lily, so he’s always on the lookout for an excuse. On those rare Saturday mornings when we still play basketball, he stops by to give me a lift. The court we play on is a few blocks from his house, but he insists the four-mile drive into the country isn’t that far out of his way. One drunken night, over a decade ago, he made the mistake of confessing to me his infatuation with Lily. The secret was no sooner out than he tried to extort from me a promise not to reveal it. “If you tell her, so help me…,” he kept repeating.

“Don’t be an idiot,” I assured him. “Of course I’m going to tell her. I’m telling her as soon as I get home.”

“What about our friendship?”

“Whose?”

“Ours,” he explained. “Yours and mine.”

“What about it?” I said. “I’m not the one in love with your wife. Don’t talk to me about friendship. I should take you outside.”

He grinned at me drunkenly. “You’re a pacifist, remember?”

“That doesn’t mean I can’t threaten you,” I told him. “It just means you’re not required to take me seriously.”

But he was taking me seriously, taking everything seriously. I could tell. “You don’t love her as much as you should,” he said, real tears in his eyes.

“How would you know?” William Henry Devereaux, Jr., said, dry-eyed.

“You don’t,” he insisted.

“Would it make you feel better if I promised to ravish her as soon as I get home?”

I mean, the situation was pretty absurd. Two middle-aged men—we were middle-aged even then—sitting in a bar in Railton, Pennsylvania, arguing about how much love was enough, how much more was deserved. The absurdity of it was lost on Teddy, however, and for a second I actually thought he was going to punch me. He had to know I was kidding him, but Teddy belongs to that vast majority who believe that love isn’t something you kid about. I don’t see how you could not kid about love and still claim to have a sense of humor.

Since that night, I’m the only one who makes reference to Teddy’s confession. He’s never retracted it, but the incident remains embarrassing. “I wish you had some feelings for June,” he says now, smiling ruefully. “We could agree to a reciprocal yearning from afar.”

“How old are you?” I ask him.

He’s quiet for a moment. “Anyhow,” he says finally. “The real reason I wanted to drive you home—”

“Oh, Christ,” I say. “Here we go.”

I know what’s coming. For the last few months rumors have been running rampant about an impending purge at the university, one that would reach into the tenured ranks. If such a thing were to happen, virtually everyone in the English department would be vulnerable to dismissal. The news is reportedly being broken to department chairs individually in their year-end conferences with the campus executive officer. According to which rumors you listen to, the chairs are being either asked or required to draw up lists of faculty in their departments who might be considered expendable. Seniority is reportedly not a criterion.

“All right,” I tell Teddy. “Give it to me. Who have you been talking to now?”

“Arnie Drenker over in Psychology.”

“And you believe Arnie Drenker?” I ask. “He’s certifiable.”

“He swears he was ordered to make a list.”

When I don’t immediately respond to this, he takes his eyes off the road for a microsecond to look over at me. My right nostril, which has now swollen to the point where I can see it clearly in my peripheral vision, throbs under his scrutiny. “Why do you refuse to take the situation seriously?”

“Because it’s April, Teddy,” I explain. This is an old discussion. April is the month of heightened paranoia for academics, not that their normal paranoia is insufficient to ruin a perfectly fine day in any season. But April is always the worst. Whatever dirt will be done to us is always planned in April, then executed over the summer, when we are dispersed. September is always too late to remedy the reduced merit raises, the slashed travel fund, the doubled price of the parking sticker that allows us to park in the Modern Languages lot. Rumors about severe budget cuts that will affect faculty have been rampant every April for the past five years, although this year’s have been particularly persistent and virulent. Still, the fact is that every year the legislature has threatened deep cuts in higher education. And every year a high-powered education task force is sent to the capitol to lobby the legislature for increased spending. Every year accusations are leveled, editorials written. Every year the threatened budget cuts are implemented, then at the last fiscal moment money is found and the budget—most of it—restored. And every year I conclude what William of Occam (that first, great modern William, a William for his time and ours, all the William we will ever need, who gave to us his magnificent razor by which to gauge simple truth, who was exiled and relinquished his life that our academic sins might be forgiven) would have concluded—that there will be no faculty purge this year, just as there was none last year, just as there will be none next year. What there will probably be next year is more belt tightening, more denied sabbaticals, an extension of the hiring freeze, a reduced photocopy budget. What there will certainly be next year is another April, and another round of rumors.

Teddy steals another quick glance at me. “Do you have any idea what your colleagues are saying?”

“No,” I say, then, “yes. I mean, I know my colleagues, so I can imagine what they’re saying.”

“They’re saying your dismissing the rumors is pretty suspicious. They’re wondering if you’ve made up a list.”

I sigh dramatically. “If I did, it’d be a long one. If we ever start cutting the deadwood in our department, we’re not going to want to stop at twenty percent.”

“That’s just the kind of talk that makes people nervous. This is no time to be joking. If you’d trust me, tell me what you know, I could at least reassure our friends.”

“What if I don’t know anything?”

“Okay, be that way,” Teddy says, looking like I’ve hurt his feelings now. “I didn’t tell you everything when I was chair either.”

“Yes, you did,” I remind him. “I remember because I didn’t want to know any of it.”

When I see that I’ve hurt his feelings, I give in a little. “I have my meeting with Dickie later this week,” I tell him, trying to remember whether it’s tomorrow or Friday.

Teddy doesn’t react to this. In fact he doesn’t seem to have heard it. Talk about paranoid. He’s watching his rearview mirror as if he suspects we’re being followed. When I turn around, I see we are being followed, tailgated actually, by a red sports car, which jerks into the passing lane dangerously, roars by, darts back in again, forcing Teddy to hit the brakes. It’s Paul Rourke’s red Camaro, I realize, and when the car pulls over onto the shoulder, Teddy follows, red-faced with impotent fury. Rourke’s wife, the second Mrs. R., whose name I can never remember, is at the wheel, but she’s clearly acting on her husband’s instructions. Though she’s normally dreamy-eyed and laconic, something aggressive surfaces when she’s behind the wheel. According to Paul, who’s been married to the second Mrs. R. long enough to become disenchanted, it’s the only time she’s ever completely awake. She’s always roaring past me on this road to Allegheny Wells, and she always graces me with a long glance before looking away again, apparently disappointed. The bored expression on her face is always the same, unimpeded by recognition.

“If a fight breaks out, she’s mine,” I tell Teddy, who’s still clutching the wheel hard.

“What the—did you see—” he sputters. He’s looking over at me to verify events. Anger is one of several emotions Teddy’s never sure he’s entitled to, and he wants to make certain it’s justified in this instance.

Rourke gets out languidly, bends back down, and leans into the car to say something to the second Mrs. R. Probably to stay put. This won’t take long. Which it wouldn’t, if a fight did break out. Paul Rourke is a big man, and the very idea of getting punched in my already mutilated nose fills me with nausea.

It takes me a while to unfold myself out of Teddy’s Civic. Rourke waits patiently, holding the door for me. When I stand up straight, I’m taller than he is, so there’s something to be grateful for, even though it’s not something of consequence. This is the same man who, several years ago, threw me up against a wall at the department Christmas party, and what worries me today is that there’s no wall. If he tosses me now I’m going to end up in the ditch. The good news is he seems content to study my ruined nose and grin at me.

Teddy has gotten out of the car and begun to sputter. “That was almost an accident,” he tells Rourke, who, so far, hasn’t even honored Teddy with a glance.

“Hello, Reverend,” I say, friendly. As a younger man, before converting to atheism, Paul Rourke was a seminarian.

“Does it hurt?” he wants to know, studying my schnoz.

“Sure does, Paul,” I assure him, anxious to please.

He nods knowingly. “Good,” he says. “I’m glad.”

When he raises his hand, I step back, trying not to flinch. In his hand there’s a camera, an expensive one, and he gets off about eight automatic clicks before I can offer him my good side.

“This is how I’ll remember you when you’re gone,” he tells me. He nods ever so slightly in Teddy’s direction. “Him, I’m just going to forget.”

Then he returns to his Camaro, which lurches back onto the pavement, spraying small stones in his wake. “That does it,” Teddy says, convinced finally, now that it’s safe, that anger is indeed an emotion appropriate to this occasion. “I’m filing a grievance.”

I laugh all the way up the winding road that leads to the house where Lily and I live. I have to dry my eyes on my coat sleeve. Teddy, I can tell, is sheepish and half angry at me for invalidating his emotions with mirth. “I mean it,” he assures me, and then I’m lost again.

Lily comes out onto the back deck when she hears a strange car pull up. She’s in her jogging clothes and she looks flushed, like she’s just finished her run. She gives us a wave, and Teddy can’t wait to get out of the car so he can wave back. We’re too far away for her to see my ruined nose, but the pose my wife has struck, hands on her slender hips, suggests that she’s prepared for lunacy.

“It’s not as bad as it looks,” Teddy hollers.

As we approach, Lily looks us over critically, trying to discover what Teddy’s remark is in reference to. I’ve been coming home with minor wounds for twenty years, but they are usually below the neck—sprained ankle, swollen knee, stiff lower back, that sort of thing. Our Saturday morning departmental basketball games, back when we all still spoke to each other, frequently resulted in injury. Often courtesy of Paul Rourke, who seemed to keep a different kind of score from the rest of us.

So what Lily is looking for is a limp. A listing to port. A stoop. And of course she can’t really see my nose because I’m purposely walking toward her with my head cocked, so as to present her with my good nostril. No easy task, considering the size of the bad one. When we reach the base of the deck, Teddy sees what I’m doing and grabs my chin and rotates it, so that Lily has the full benefit of my mutilation. I wonder if Teddy is as disappointed as I am by her reaction, an arched eyebrow, as if to suggest that even so bizarre an injury was entirely predictable, given my character.

“The man is out of control,” Teddy says admiringly.

We go inside because it is still chilly in mid-April and the temperature is dropping with the sun down. I hear Occam whimpering to be let out of the laundry room, to which Lily banishes him when he’s been a bad dog. When I open the door, the dog, beside himself with joy, bolts past me and does a frantic lap around the kitchen island, his nails scratching for traction on the tile floor, before he spies Teddy, whose face blanches. Occam is a big dog, a nearly full-grown white German shepherd who’d appeared in our drive almost a year ago. Lily heard him barking, and we went out onto the deck to study the odd spectacle the dog presented. He stood in the middle of the drive as if he’d been instructed to remain there but doubted the wisdom of the command. He seemed to want a second opinion from us. “I think he wants us to follow him,” Lily said. “Where do you suppose he came from?”

“If he wants us to follow him, he came from television,” I said, but in truth that’s what he did look like standing there, barking at us without advancing. Actually, he’d start to come toward us, then appear to remember something horrible, yelp in a completely different register from his bark, retreat a few steps, and start the whole process over again.

We approached cautiously, stopping a few feet from the animal, which was now wagging his tail wildly and grinning at us in a lopsided, rakish manner.

“I’ve never seen a dog grin like that,” Lily observed. “He looks like Gilbert Roland.”

I was curious about a glint in the dog’s mouth. He looked for all the world like he had a gold tooth.

“Lord, Hank,” Lily said. “I think he’s snagged.”

Which was exactly the animal’s problem. What I had perceived as a gold tooth was a treble hook embedded in the dog’s lip. He was trailing a long tether of monofilament line, invisible except when the dog strained against it, resulting in that Gilbert Roland smile. Lily held him steady while I bit the line in two. He’d been trailing about a hundred yards of it, apparently all the way up from the lake, two miles away. Back in the house, under Lily’s gentle hand and voice, he waited patiently for me to find a pair of wire cutters, nor did he move when I snipped the shaft and removed the hook. “Okay,” he seemed to say when the hook was out. “Now what?”

We advertised, put signs up around the neighborhood, but no owner ever came forward, so there was nothing to do but feed the animal and watch him double in size. Since his arrival, we’ve had few visitors, a fact Occam clearly cannot understand, given how much he enjoys them. He’s so elated at seeing this one that he’s immune even to the sound of Lily’s raised voice, which usually causes him to quake. Teddy, who hasn’t seen Occam since his face-licking stage, raises both arms to protect himself. Occam, no longer a face licker, executes his favorite move, the one he uses on all strangers, irrespective of gender. When Teddy’s arms go up, Occam burrows his long, pointed snout in Teddy’s crotch and lifts, as if he imagines he’s got Teddy impaled on the end of his wet nose. In fact, Teddy goes up on tiptoes, furthering the illusion.

“Occam!” Lily bellows, and this time her voice penetrates the animal’s canine joy. He lowers Teddy and looks around just in time to catch a rolled-up newspaper on the snout. Yelping pitifully at this reversal of fortune, he slinks across the floor, dragging his haunches in melodramatic humiliation, yelping every step of the way. My own snout throbs in sympathy.

“Good dog!” I tell him, just to confuse things, and Occam’s tail comes out from between his legs, darts back and forth, sweeping the floor.

Lily helps Teddy onto one of the stools that ring the kitchen island while I take Occam out onto the deck, where he clatters noisily down the steps. It’s his plan to do several furious laps around the house to dispel the humiliation. I know and understand my dog well. We share many deep feelings.

Back inside, the blood is returning to Teddy’s face. “Lily taught him that trick,” I explain, adding, “I thought he’d never learn it either.”

“It’s a good thing you’re already injured,” Lily says, as if she means it. She’s both flustered and embarrassed by Teddy’s have been groined this way. She’s a woman who naturally tends to injuries, and she’s trying to think of a way to tend to this one of Teddy’s.

“I want you to know that a good-looking woman did this to me,” I tell her.

Teddy quickly fills her in. “Gracie,” he explains.

“Gracie is no longer a good-looking woman,” my wife reminds us. “I’m much better looking than she is since she got fat.” She’s gone to the counter and returned with a carafe of steaming coffee.

Teddy is considering telling her that she was always better-looking. I can tell by the pitiful, lost look on his face. He actually opens his mouth and then closes it again. In fact, Lily does look wonderful, it occurs to me. Slim, athletic, aglow, she runs a couple miles a day, and if her muscles ache like mine do after a run, she keeps those aches a secret, feeling perhaps, that complaining about aches derived from athletic endeavor is male behavior. She does not have a high opinion of male behavior in general.

“What did she use on you,” she says, now that she’s had a chance to examine my schnoz close up, “a shrimp fork?”

When Teddy tells her it was the ragged end of Gracie’s spiral notebook that she used to gig me, Lily winces, testimony, I’d like to think, to her continued tender feeling for me. Teddy launches into an enthusiastic but imaginatively pedestrian account of the personnel committee meeting that has resulted in my maiming. His entire emphasis is on my goading of Gracie. He misses all the details that even an out-of-practice storyteller like me would not only mention but place in the foreground. He’s like a tone-deaf man trying to sing, sliding between notes, tapping his foot arhythmically, hoping his exuberance will make up for not bothering to establish a key. It makes for painful listening, and I privately edit his account—restructuring the elements, making marginal notes, subordinating, joining, cleaving, reemphasizing. I even consider writing up my own version for the Railton Daily Mirror (known affectionately to the locals as The Rear View). Last year I did a series of op-ed satires under the heading “The Soul of the University,” deadpan accounts of academic lunacy under the pseudonym Lucky Hank. A narrative of today’s personnel committee meeting might resurrect the series.

Whether it should be resurrected is another issue. Past installments have raised the ire of university administrators and my colleagues, both of whom have accused me of a lack of high seriousness, of undermining what little support there is in the general population for higher education, and of biting the very hand that feeds me. A well-written account of my maiming today would not even require exaggeration to achieve the desired absurdist effect, as Teddy’s pedestrian telling proves, but his account lacks something vital. As I tell my students, all good stories begin with character, and Teddy’s rendering of the events fails entirely to render what it felt like to be William Henry Devereaux, Jr., as the events were taking place.

William Henry Devereaux, Jr., had, in fact, been suffocating. Phineas (Finny) Coomb, as chair of the personnel committee, had chosen a small, windowless seminar room for us to meet in. Understandable, since there were only six of us. Except that two of the six—Finny himself and Gracie DuBois—were heavily perfumed, and William Henry Devereaux, Jr., had gotten up three times to open a door that was already open. Teddy, his wife, June, and Campbell Wheemer (the only untenured member of our graying department) all seemed to be in complete control of their gag reflexes, but William Henry Devereaux, Jr., was not.

“Are you all right?” Wheemer interrupted the proceedings to inquire. He was only four years out of graduate school at Brown, and he wore what remained of his thinning hair in a ponytail secured by a rubber band. After being hired he had startled his colleagues by announcing at the first department gathering of the year that he had no interest in literature per se. Feminist critical theory and image-oriented culture were his particular academic interests. He taped television sitcoms and introduced them into the curriculum in place of phallocentric, symbol-oriented texts (books). His students were not permitted to write. Their semester projects were to be done with video cameras and handed in on cassette. In department meetings, whenever a masculine pronoun was used, Campbell Wheemer corrected the speaker, saying, “Or she.” Even Teddy’s wife, June, who’d embraced feminism a decade earlier, about the same time she stopped embracing Teddy, had grown weary of this affectation. Lately, everyone in the department had come to refer to him as Orshee.

“I’m fine,” I assured him.

“You were making funny noises,” Orshee explained.

“Who?”

“You.” Four voices seconding my young colleague’s observation: Finny’s, Teddy’s, June’s, Gracie’s.

“You were … gurgling,” Orshee elaborated.

“Oh, that,” I said, though I had not been aware of gurgling. Gargling perhaps, on Gracie’s cloying, heady perfume, but not gurgling. Was it her proximity in the small, airless room, or had she made a mistake this morning and applied her perfume twice?

Looking at Gracie now, you had a hard time remembering the effect of her hiring twenty years ago. She had been like one of those dancers in black fishnet stockings and tails and a top hat, being passed from hand to sweaty hand over the heads of an otherwise all-male revue. As Jacob Rose, then our chair and now our dean, was fond of observing, every man in the college wanted to fuck her, except Finny, who wanted to be her. That was then. I doubt we could hoist her over our heads now. We’re not the men we used to be, and Gracie is twice the woman. The sad thing is that anybody has only to look at Gracie (or, in my case, catch a whiff of that perfume) to know she still wants to be that woman. And, hell, we understand. We’d like to be those men.

“Would you quit staring at me?” Gracie turned to face me, alarmed. “And would you quit sniffing like that?”

“Who?” I said.

“You!” Four voices. Finny’s, Teddy’s, June’s, Orshee’s.

“Does the chair have anything to report on the status of the search?” Finny inquired. Finny was dressed today as he was dressed every day after spring break, in a white linen suit and pink tie that showed off to great advantage his recently acquired Caribbean tan. Several years ago he’d let his white hair grow bushy, then hung a large color portrait of Mark Twain in his office, which he was fond of standing next to.

“Limbo,” I reported. Our search for a new chairperson had gone pretty much as expected. In September we were given permission to search. In October we were reminded that the position had not yet been funded. In December we were grudgingly permitted to come up with a short list and interview at the convention. In January we were denied permission to bring anyone to campus. In February we were reminded of the hiring freeze and that we had no guarantee that an exception would be made for us, even to hire a new chair. By March all but six of the remaining applicants had either accepted other positions or decided they were better off staying where they were than throwing in with people who were running a search as screwed up as this one. In April we were advised by the dean to narrow our list to three and rank the candidates. There was no need to narrow the list. By then only three remained out of the original two hundred.

“Is the dean pushing?” Finny wanted to know. This was the sort of thing I should be able to find out, he was suggesting, since Jacob Rose and I were friends. My not having concrete information to report was evidence to Finny, were any needed, that I was attempting to scuttle the search for a new chair, a search I’ve not been in favor of from the beginning. My position has been that our department is so deeply divided, that we have grown so contemptuous of each other over the years, that the sole purpose of bringing in a new chair from the outside was to prevent any of us from assuming the reigns of power. We’re looking not so much for a chair as for a blood sacrifice. As a result of my stated position, Finny suspects that the dean and I are secretly attempting to subvert both the search and the department’s democratic principles.

“I believe it would be accurate to describe the dean as more pushed against than pushing,” I reported.

“He’s a wimp,” June agreed, though she and Teddy are also friends with Jacob.

“Or she,” I added, apropos of nothing.

Orshee looked up, confused. This was his line. Had he missed an opportunity to say it?

“Why are we here?” Teddy wondered, not at all philosophically. “Why not wait until the position has been approved before ranking the candidates? This is liable to take hours, and we have no guarantee that the position won’t be rescinded tomorrow, in which case we will have wasted our time.”

“The dean has requested that we rank the remaining candidates,” Finny intoned, “and so rank them we shall.”

Common sense efficiently disposed of, endless discussion of the three remaining candidates ensued. Twice I had to be requested to stop gurgling. Three times I beat Campbell Wheemer to his “or she” line. No one seemed able to recall what had attracted us to these three candidates to begin with. I doubted, in fact, that we ever were attracted to them. They represented what was left after we’d winnowed out the applications that were personally threatening. To hire someone distinguished would be to invite comparison with ourselves, who were undistinguished. Not that this particular logic ever got voiced openly. Rather, we reminded each other how difficult it was to retain candidates with excellent qualifications. To make matters worse, we were suspicious of any good candidate who expressed interest in us. We suspected that he (or she!) might be involved in salary negotiations with the institution that currently employed him (or her!) and trying to attract other offers to be used as leverage with their own deans.

Gracie was anxious to whittle the final three applicants down to two, having discovered something alarming about the third. “Professor Threlkind is an untenable candidate given our present scheme,” she pointed out. As she spoke, she referred to notes on the untenable Threlkind that she’d written down in her large spiral notebook. During the course of our personnel committee meetings, she’d worried the spiral out of its coil, so that its hooked, lethal end was exposed, using it to chip flecks of lacquer from her raspberry thumbnail. “We’re already overstaffed in Twentieth Century,” she reminded us. “Also, we have no demonstrated need for a second poet,” she added, since the candidate had listed several poetry publications in little magazines.

The reason the untenable Threlkind was still part of our deliberations was that Gracie had come down with the flu last November and missed the meeting at which she might have had him dismissed from further consideration. Her own field was Twentieth-Century British, and she’d desktop-published, just last year, a second volume of her poetry. If the untenable Threlkind were hired, Gracie would have to share courses in these areas, courses that she had long considered her own private stock.

“And I’d also like to point out that the candidate is yet another white male,” she concluded, closing her notebook in a gesture of finality.

“Do we already have a poet?” I heard William Henry Devereaux, Jr., inquire innocently. Teddy and June stared at their hands, traces of smiles curling their lips. They had a long list of political enemies, and Gracie was near the top, having been part of the coalition that had brought Teddy down off his chairmanship.

“That’s an out-of-order remark,” Finny declared without conviction, and I caught a whiff of his minty breath mixing dangerously with Gracie’s perfume.

“I think we should eliminate both male candidates,” Orshee offered.

“Are you suggesting that we not consider male candidates?” Teddy wondered. “Simply on the basis of gender?”

“Exactly,” Orshee replied.

“That would be illegal,” Teddy said, but his voice didn’t fall quite right, leaving an implied “wouldn’t it?” hanging in the air.

“It’d be moral,” Orshee insisted. “It’d be right.”

“Still, it’s not the procedure we followed when we hired you,” Finny reminded him. Finny, who’d come out of the closet several years ago and then gone back in again, had even more reason than the rest of us to be disappointed in our young colleague. He’d been Orshee’s most vocal advocate, having apparently concluded on the basis of several remarks made during his interview that Campbell Wheemer was gay, whereas it turned out that all Orshee was trying to imply was that gay people were fine with him, as were black people and Asian people and Latino people and Native American people. In fact, Orshee would have preferred to be one of these people himself, politically and morally speaking, had the choice been his. Bad luck.

“You should have hired a woman,” Orshee continued. He seemed on the verge of tears, so deep were his convictions in this matter of his having been hired over a qualified womaṇ. “And when I come up for tenure, you should vote against me. If we in the English department don’t take a stand against sexism, who will?”

This time even I was aware of my gurgling.

“I’m not in favor of eliminating both male candidates,” Gracie clarified her position. “Just Professor Threlkind. Because we don’t need another white male. Because we don’t need another person in Twentieth Century. Because we don’t need another poet. That’s three strong reasons, not one.”