13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

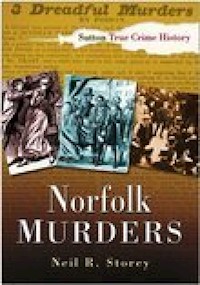

Contained within the pages of this book are the stories behind some of the most notorious murders in Norfolk's history. The cases covered here record the county's most fascinating but least known crimes as well as famous murders that gripped not just Norfolk but the whole nation. From the Burnham Poisoners of 1835 to the Yarmouth Beach Murders, from the Costessey Horror to the 'last judicial beheading in England', this is a collection of the county's most dramatic and interesting criminal cases.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Norfolk

MURDERS

Norfolk

MURDERS

NEIL R. STOREY

First published in 2006 by Sutton Publishing

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© Neil R. Storey, 2006, 2012

The right of Neil R. Storey, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8427 3

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8426 6

Original typesetting by The History Press

To ex-Chief Inspector Alan Chapman of Norfolk Constabulary, a fine copper and a good friend.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. The Burnham Sickness

Burnham 1835

2. The Stanfield Hall Murder

Wymondham 1848

3. The Repentance of William Sheward

Norwich 1851

4. The Last Judicial Beheading in England

Walsoken 1885

5. The South Beach Murders

Great Yarmouth 1900 and 1912

6. Valentine’s Tragedy

Norwich 1903

7. A Forgotten Cause Célèbre

Norwich 1905–6

8. The Catton Horror

Catton 1908

9. The Killing of PC Charles Alger

Gorleston 1909

10. The Last To Hang in Norfolk

Old Catton and Dereham 1951

Select Bibliography

Norwich Castle, c. 1875. Hangings drew large crowds. On execution days the scaffold was usually erected between the gatehouses and the concourse over the cattle market.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I have been granted privileged access to numerous public and private archives and collections in the preparation of this book, and so to all – too numerous to mention – who have opened their doors to me, I say a genuine thank you. It has been proved, yet again, that when researching some of the darkest tales from Norfolk’s past, I have met and renewed the acquaintance of some of the nicest people.

I am also grateful for the kind and fascinating letters, compliments, and snippets of information, I have received from readers of my regular ‘Grisly Tales’ features in the Norfolk Journal. Naturally, I wish to extend my thanks to all of them, but must find space to offer my gratitude to the following, without whose help, enthusiasm, generosity and knowledge, this book would not have been so enriched: my friend and esteemed fellow crime historian, Stewart Evans and his good lady Rosie; James Nice; Alan and Joan Chapman; Robert ‘Bookman’ Wright; BBC Radio Norfolk; the late Syd Dernley; Jayne Whitwell; Brian Wild; John Forbes; Ken Jackson; Ray Noble; Peter Watson at Family Tree magazine; Clifford Elmer books; Les Bolland books; Philip Goodbody at Doormouse Bookshop; Brian Symonds at Burnham Market Pharmacy; Norfolk Probation Service; The Tolhouse Museum, Great Yarmouth; The Shirehall Museum and Bridewell at Walsingham; Wymondham Bridewell Museum; Norwich Castle Museum; Freda Wilkins-Jones and all the helpful staff at the Norfolk Record Office; University of East Anglia Library; the encyclopaedic knowledge of Michael Bean at Great Yarmouth library; Clive Wilkins-Jones and the superb staff at Norfolk Heritage Library; my friends amongst the past and present serving officers of Norfolk Constabulary; and of course, my old friends at the Norfolk Constabulary Archive.

Finally (but by no means least), I thank my family: especially my dear son Lawrence and my beloved Molly, for their love and support during the research of this book.

Note: all the photographs and illustrations are from the author’s collection unless otherwise credited. All the modern photographs of murder sites, localities and gravestones have been specially taken by the author for this book in 2005 and 2006.

A broadsheet sold at the execution of James Rush, 21 April 1849.

INTRODUCTION

Norfolk is one of England’s five largest counties. An extensive outland of agrarian fields stretching from the eastern flank of Britain, almost half of the county is bounded by sea. Over much of the period covered by this book, Norfolk was not overpopulated, and many towns and village communities were still, by today’s standards, insular and remote. The industrial towns of the North and ‘big smoke’ of London seemed a world away: their advanced transport systems, communications, density and diversity of human life sharply contrasting with the country ways of life. Back then, attitudes to life and death were very different. Families were larger, and it was a sad fact of life that due to epidemic diseases, bad sanitary provision and lack of affordable medical care, many did not make it to maturity. Widowhood and mourning black were the order of the day for numberless people for much of their lives.

Before the Temperance Movement took off in Norfolk, from about the 1880s, the local pub was the focal point of any village celebration, holiday or entertainment. Mind you, the path to temperance or ‘blue ribboning’ was not a smooth one: both men and women of the ‘rough order’ took exception to what they considered meddlesome interference by organisations like the Salvation Army (or as they called them, ‘The Skeleton Army’), pelting them with whatever came to hand in the gutter as they paraded. Hence, the early bonnets worn by female Salvationists were more for protection than uniform appearance! In those days, men spent most of their spare time in pubs, perhaps taking part in pub sporting events such as skittles or quoits: but it still meant they were drinking. Indeed, a recurring theme in a number of Norfolk murder cases is the fact that the culprit was known to have been ‘in drink’, or even a habitual drunkard whose mind had become unhinged by alcohol abuse.

For most Norfolk people in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries news was disseminated by word of mouth, newspapers and periodicals. In many areas country folk would eagerly await the arrival of the town and village carriers, bringing the latest news from the big towns and the city. As ever, a local murder always attracted a premium of interest: from the horror of its discovery, through the tracking of the murderer, and on to the trial – people often forming their own opinions for or against the accused. If the case had gained some notoriety the papers would be filled with columns detailing every aspect of the case, and many would eagerly watch for the jury’s verdict: for if it was ‘Guilty’ they could be in for what they considered a treat! Before the public execution of felons was banned by parliament in 1868 and removed out of sight behind prison walls – in the days before professional football matches, film shows and television – a hanging was a real ‘event’. Thousands of men, women and children – numbers equalling that of football match capacity crowds – would fill the open ground and cram into the windows of nearby houses to watch the proceedings. Many would have set out in the wee hours of the morning, walking miles to guarantee themselves a good view of the execution.

Most executions in Norfolk were carried out in front of the old County Gaol at Norwich Castle, between the two small gatehouses at the foot of the entrance slope. Crowds would spread across the horse and cattle market, temporary wooden stands would be built to enable grandstand views, while the gentry paid handsomely for private rooms in buildings overlooking the scaffold. As the crowds gathered, ‘long song sellers’ sold broadsheets recounting the story of the murder and probably the criminal’s condemned cell confession in words, pictures and poetry. Gin and tea wagons sold brews by the cup, while hawkers of hot pies, potatoes, pastries and fancies did a good trade – as did the pickpockets, who regularly managed quite a haul of purses and watches at such events.

As the appointed hour approached, the great bell of St Peter Mancroft church would toll away the final minutes. Then an entourage of civic dignitaries with attendant javelin men and prison officials filed out from the prison gates, followed by the Prison Chaplain and the condemned felon, flanked by Governor and warders. It was quite a spectacle. Upon arrival at the scaffold an expectant hush would fall over the crowd, and as the condemned man or woman mounted the steps of the gallows, cries of ‘Hats off!’ came from the crowd. This was not a mark of respect, but a desire for a better view from those at the back. With an adjustment of the rope, and the pulling down of a white hood, the executioner – the ‘Lord of the Scaffold’ – would push the lever, release the trapdoor, and the condemned would be plunged to eternity. Connoisseurs among the crowd noted the efficiency of the executioner by the speed with which signs of life departed from his victim.

If the executioner thought the drop had not gone well he would nip down below the scaffold and pull on the legs of the person being ‘swung’, to hasten them on their way. The body would then be left to hang for the appointed hour, to ensure all life was extinct, and as a grim warning for all to see. The body would then be taken down and the crowd would depart. But, in the days when the bodies of executed criminals were passed to surgeons for dissection, a few hardy souls would have lingered to view the body in the ‘Surgeon’s Hall’, after the initial cuts had been rendered. And even in the years after dissection of executed felons had ceased, it was not unknown for the prisoners of the County Gaol to be paraded in the exercise yard as the corpse was wheeled through in an open ‘shell’ coffin for all to see. Even up to the last days of hanging, it was customary for the bodies of those who had been executed to be buried and covered with quicklime (to hasten decomposition) within the precincts of the prison where they had been hanged. The initials of the executed person and the year of their execution, carved into a white stone let into the wall nearby, was the only grave marker allowed.

The Victorians, so proud and willing to extol the virtues of morality and ‘sensibilities’, were satisfied with the removal of the ‘animal spectacle’ of public executions to within the prison walls: out of sight, out of mind . . . or was it? The hypocrisy of the situation is revealed when sales of righteous publications and religious journals, such as Home Words or The Quiver (said to be ‘worthy of a place in every home’), were being eclipsed by lurid products of the gutter press, like the infamous Illustrated Police News and the equally graphic Penny Illustrated Paper. Furthermore, publications such as the Famous Crimes Series, edited by Harold Furniss, were enjoyed well into the late Edwardian period. Thus, removal of the spectacle of public execution only seemed to fuel a morbid interest in it, adding to the mystique and fascination of the dark netherworld of crime and criminals – and especially murderers.

In this book it is my privilege and pleasure to share with the reader many previously unpublished, or long unseen, accounts and photographs, relating to some of the most infamous, intriguing and notable crimes ever committed in the fair county of Norfolk. In the course of research I have visited most of the sites involved, actually standing on spots where several of the murders took place. My investigations have even led me to visit some of the prisons and bridewells where the perpetrators were held. For instance, accompanied by a party of my WEA students, I visited the remarkable and unspoilt Walsingham Bridewell, where Fanny Billing and Cat Frary (her name is also spelt as Frarey in some accounts) were interrogated and held for months pending trial. The atmosphere lingering in its dark corridors and tragic cells was so intense, so oppressive and sad, that some of my students were unable to remain inside and immediately walked out. Today, some of the sites have been altered beyond recall or demolished, like James Rush’s home, Potash Farm, or the cottages where the Burnham poisoners lived. Most of the sites look innocent enough now, cluttered with housing and business developments, with motor cars roaring past: yet a shudder can still run down your spine when you consider what happened there. Standing by the graves of some of the victims, especially having studied their cases, one feels moved by the simple stones, which often give little clue to the story behind them.

I have had a chance to see for myself original letters written in the hand of some of the criminals featured in these stories, the same hands that committed the most abominable of deeds. From America I obtained a copy of The Trial of James Blomfield Rush with annotations by a member of the prosecuting counsel. I have even held the full head and neck death mask of Rush, a cast that, chillingly, still clearly evinced the deep ridge forged into his neck by the rope that hanged him. To me, the most fascinating of all paperwork was to find the death warrant for the execution of Robert Goodale – one of the most infamous executions of all time – in the Norfolk Records Office. I have touched some of the relics of the crimes: most movingly, the mangled collar numbers blasted from the uniform of PC Alger by a mentally unstable ne’er-do-well wielding a shotgun. And finally, having rediscovered Norfolk’s all-but-forgotten cause célèbre of the Edwardian period, I have managed to track down an original photograph of the woman at the centre of it all – Rosa Kowen.

The Judge leaving Norwich Cathedral after the Assize service, c. 1912.

In recounting these ten cases I hope I can convey some of the lasting impressions from my research. To this end, I have attempted to recreate the atmosphere of past times and past crimes by evoking the language and details of contemporary accounts. These I have carefully blended with as much original source material, witness statements, coroners’ reports and original court records as possible, in an attempt to strip away the myths that have become attached to these crimes over the years. Indeed, it proved to be the case that each original, unvarnished tale required no embroidery to amaze and appal. In fact, these stories – with their memorable characters and their intriguing twists and turns – have proved, yet again, Byron’s adage: ‘Truth is strange, stranger than fiction.’

Neil R. Storey

Norfolk 2006

1

THE BURNHAM SICKNESS

Burnham 1835

The seven Burnhams are villages dotted along the upper edge of the Norfolk coast. These attractive settlements are blessed with a combination of big skies, fine countryside, and rivers that snake towards quiet bays and the sea. Today they are beloved by holidaymakers and second homeowners, but in the nineteenth century they were rural hamlets of close-knit communities with a strong reliance on agriculture, coastal trading, and a long history of smuggling. In 1835 Burnham Market and its adjoining hamlet of Burnham Westgate was a community of 1,126 inhabitants. Life was simple and there were still many who not only believed in, but relied on, folklore to ensure good harvests, administer medical needs, and even find love. Death was common: parents accepted that not all of their children would make it to maturity, and consequently, families were larger than they are today. And in Victorian times there was always a fear of epidemics and diseases, especially smallpox, consumption (tuberculosis) and cholera.

Folks here lived close by one another, many of them in small rows of cottage homes, which often had shared yards, pumps, adjoining workshops and stables. On one of these roads, known today as North Street, just off Burnham’s marketplace, lived the Billing, Frary and Taylor families. Their row of cottages led off from the street at a right angle. Nearest the road, living in the cramped rooms above Thomas Lake’s carpenter’s shop, were Robert and Catherine Frary with their three children. Next to them were Peter and Mary Taylor, and finally, on this little row, lived James and Frances ‘Fanny’ Billing with a number of their children.

Two sudden deaths occurred in quick succession within the Frary household early in March 1835, leaving poor Cat Frary (aged forty) mourning for the loss of her husband and a child who had been staying with her. There was public sympathy for her, but inevitable questions were raised in fear of some contagion having manifested itself in the Frary home. Time passed, however, and as no one else showed signs of falling victim to the mysterious ‘Burnham Sickness’, the matter died down and the village returned to normal for a few weeks. But then Mary Taylor (wife of Peter Taylor, aged forty-five, a journeyman cobbler who was a neighbour and friend of the Frarys) was taken violently ill and dropped dead on the evening of 12 March. Mr Cremer, the local surgeon had been summoned by Cat Frary and Phoebe Taylor (Mary’s sister-in-law) but could do nothing for poor Mary. Surgeon Cremer’s suspicions were aroused by this sudden death and an inquest was called for the following day, before Mr F.T. Quarles, Coroner for the Duchy of Lancaster. At the inquest it was suggested that Peter Taylor had been ‘associated’ with Fanny Billing (aged forty-six), a mother of eight children (she had given birth to a total of eleven children but three had died in infancy), who was described as ‘a woman of loose character’, but this dalliance was not immediately considered relevant to the crime. The contents of Mary Taylor’s stomach had been analysed and found to contain arsenic in such a quantity it had caused her death. The jury returned a verdict of death by poisoning: but exactly how, and by whose hand, remained unknown. But the groundswell of suspicion within Burnham fell on Mary’s slothful and unfaithful husband, Peter Taylor.

Further enquiries soon revealed that Fanny Billing had recently bought arsenic from the local chemist, Henry Nash. When questioned about this, Billing claimed she was buying it to poison rats and mice for a Mrs Webster of Creake – a statement Mrs Webster flatly denied. A poke (small sack) of flour from the Taylor house had been tested and traces of arsenic were found: this was enough for local magistrates Frederick Hare and Henry Blyth to remand Peter Taylor and Fanny Billing to Walsingham Bridewell for further questioning.

The marketplace, Burnham in 1900 had changed little since 1835.

As Billing was escorted by constables to the cart that would take her to the bridewell, Frary was quoted as calling out: ‘Mor, hold your own and they cannot hurt us.’ This outburst was quoted in early accounts as being the cause of Frary’s immediate arrest, but that was not quite the case. Rather than relying on the spurious claim that Frary made that statement, further investigations led to more solid grounds for her arrest in connection with the murder. Both Cat and Fanny were known to consult witches or ‘cunning folk’ at Burnham, Sall and Wells. On the afternoon of Fanny’s arrest Cat asked Fanny’s son, Joseph, to hire her a horse and gig for a drive to Sall, in order to see a woman who – as Joseph recalled – ‘was something of a witch, that that woman might tie Mr Curtis’s tongue [Mr Curtis was the keeper of the Walsingham Bridewell] so that he might not question my mother.’ Frary’s close friendship with Billing, combined with their trips to the witches and the poisoning of Mary Taylor, revived the questions that still surrounded the mysterious death of Frary’s husband and the child staying with them. These factors led to Cat Frary being taken into custody for questioning.

As the weight of evidence against her was revealed through questioning, Cat Frary – who had appeared so ‘cock sure’ – soon buckled under the pressure and went into rapid physical and mental decline. Needless to say, the alchemy of the witches did nothing to hold the tongue of Mr Curtis. Worse still, comparisons were drawn with a woman named Mary Wright, from the nearby village of Wighton, who had murdered her husband by administering arsenic only a few months before the Burnham deaths: and Mary Wright, Billing and Frary were known to have consulted the same ‘cunning woman’ or ‘witch’ – Hannah Shorten of Wells. Shorten’s ‘love-spells’ were known to consist of arsenic and salt mixed together and then thrown on the fire. For most Burnham people, it did not require a great leap of imagination to see the likes of the accused mix the poisonous concoction in the food of one who would have obstructed their ‘sinful desires’.