7,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

What would you do if your dream sailing adventure turned into a nightmare of captivity? How would you protect your children when surrounded by armed child soldiers in a war-torn country? One family's harrowing true story of survival during the Mozambican civil war will forever change how you view the fragility of freedom.

When architect David Muller, his marine biologist wife Sandy, and their two young children embarked on a sailing trip to the Bazaruto Archipelago, they never imagined becoming hostages of the notorious Renamo rebels. Their idyllic voyage aboard their yacht Arwen transforms into a desperate fight for survival as they're forced to navigate the treacherous landscape of civil war-torn Mozambique. Through the eyes of this ordinary family thrust into extraordinary circumstances, we witness the brutal realities of a conflict where children become soldiers and innocence is shattered by violence. David and Sandy's firsthand account provides unprecedented insight into the complex dynamics of captivity, where their captors display both shocking brutality and unexpected humanity. Their story reveals the incredible resilience of the human spirit, as they struggle to protect their children's innocence while facing unimaginable moral dilemmas and the constant threat of death.

This raw and powerful account goes beyond a simple survival story, offering profound insights into human nature, family bonds, and the true cost of war. Through the Mullers' journey, readers will gain a deeper understanding of both humanity's capacity for cruelty and its remarkable resilience in the face of adversity.

Get your copy today and witness an extraordinary tale of survival that will forever change your perspective on freedom and family bonds.

Here are some reviews from the first edition of this book:

The books gives a unique glimpse into the reality of war and the hardships endured by all participants. The family, which includes two very young children, survives thanks to their resilience and resourcefulness, and also thanks to the kindness of ordinary people caught in the net of warfare. A remarkable book. Read it, it will help you understand the human condition a little more fully!

Reviewed in Canada - September, 2020

This book held me spellbound and I could not put it down. Descriptive and honest making it believable and challenging

Reviewed in Australia - January, 2020

Not Child’s Play is an absolute page turner and a remarkable and detailed account of a families terrible and often bizarre ordeal.

Go Travel Magazine – April 2020

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 454

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

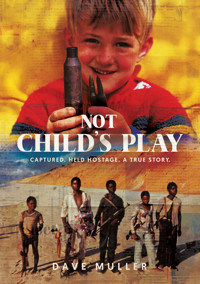

Captured. Held Hostage. A True Story

Not child’s play

The true story of a family held hostage by child soldiers in Mozambique.

David Muller

Dedicated with love to Sandy, Tammy and Seth

And with thanks to all who took part in Operation Cashmere

Prologue

To die will be an awfully big adventure.

JM Barrie, Peter Pan

‘Renamo. Boys no scare. They listen. They listen orders. They listen. No run away like Frelimo women. They no scare die. They fight!’

Paul Patrick, Renamo Commander describing his troops.

The date is 28 April 2013 and I am in Burundi as an architect, part of a volunteer group of building professionals assisting with the replanning of a run-down mission hospital, a victim of the wave of hatred that poured over Burundi and neighbouring Rwanda in 1994. The hospital is itself a trauma case. Our efforts are a first step towards resuscitation and the dream of it becoming the academic teaching hospital for the optimistically named Hope Africa University, based 60 kilometres north in the capital, Bujumbura.

The founders of Kibuye Hospital chose their site well. We are high, 1750 metres above sea level, the most southerly source of the Nile dribbling from a rocky seep just a few kilometres away. So even though we are almost on the equator, the climate is crisp, and as the evening gloom drenches the softly creased highlands, a reviving coolness washes over the countryside and spills into the valleys. Our team sits around an archipelago of hastily assembled tables, focused on our evening meal. Outside, anticipating its own dinner, the resident scops owl chirrs warnings into the grey twilight from the tall eucalyptus trees.

We’ve been together for four days and, as is the daily routine, Phil asks one of the team to explain what motivated them to volunteer. This night, of all nights, the lot has fallen on me. I can short-circuit my story and leave out the detail, but the sight of throngs of expended women, hollow-chested old men and sad-eyed children has scraped away the scar tissue protecting my memories. This place has exposed them, and the date – even the hour – seems portentous, and so my memories bleed.

Exactly 23 years ago I was blundering through darkness, trying to keep up with the boys ahead, guided more by sound than sight as we crash and stagger through the coastal dune forest. Sandy and Tammy stumble behind me. Another boy prods us forward with his AK-47. Seth clings to my sweat-sodden back.

I have an overwhelming need to tell the story. To dilute the horror in exculpation. I’m back there. Vivid memories – sights, sounds, tastes and smells – still lurk. How do I explain this overwhelming sense of being tainted, contaminated, maybe even infected by something horrible and repressed; something to which we all too glibly assign the word ‘evil’? How do I explain this irrational feeling I’m carrying, buried deep inside me, the pain of knowing first-hand the trauma of Mozambique’s past.

I’ve sensed that same burden here in Burundi, a country that has faced two genocides. Everyone we’ve met is gentle and moving along with the slow diurnal pace of their lives. But always, always, there is a hesitation, a void left in conversation. Don’t ask about the past. Some things cannot be explained, so don’t go there. Rather press forward, trusting that maybe, just maybe, cleansing and a step toward redemption can be found in acts of kindness. Maybe that is why I am here. To reclaim an innocence through acts of giving and service. To trust that I can find healing in self-sacrifice. And so I brandish this sign of hope like a crisp washed-white garment that at this moment is focused on the resurgence of Kibuye Hospital.

I launch into my story and, in the camaraderie of new friendships, I feel comfortable telling it. That is until I reach the point two hours after sunset on 28 April 1990, 23 years ago to the hour, when we – me, Sandy, my wife, and our two children, eight-year-old Tammy and five-year-old Seth – found ourselves seated in a shallow clearing, the soft, downy star-glow above defining a wall of dark vegetation around us. The elderly couple, our fellow captives, are not with us, the implication missed. We’re exhausted, soaked in sweat, terrified, and profoundly lost when those sounds come from the darkness. Once again I hear them clearly in my head. Slushy, sucking, stabbing wet sounds just metres away.

Too late I realise I should not have ventured there with my story. I should have skirted this moment that has so viscerally exposed humanity’s brutality. This has happened before and the memories, the burden, flood me. My voice is lost amid the sobs.

My listeners, of course, don’t know how to react. I am back in Mozambique, but I hear them like a distant shadow of sound. There is concern in their voices. ‘Are you all right? What’s wrong?’ All I can choke out are words formed elsewhere, far away, in a distant time. I have no control over them, they just come, and come, and come, without bidding.

‘They were just children.’ All I can say again and again as I struggle for breath is, ‘You don’t understand … they were just children.’

Afterwards, there are many apologies, but it is not their fault. I went where I knew danger lurked, unlocking strong rooms of the mind best kept shut. Surely, after all these years, those memories would by now be softened, even erased. A few days later someone kindly suggests I visit a psychologist once I get home to South Africa. They are probably right, but I decide it is time for purging. Time to tell this story.

So, once back home, I find the cardboard box containing the relics from that time. A collection of photographs and newspaper clippings. Old exercise books filled with children’s writing and drawings. A postcard of a man in a military uniform. A fifty-rand banknote. A few spent bullets and empty cartridges. The beautiful woven basket given as a gift. The carved wooden dice, spoons and the cleft sticks used for drying fish. The palm-frond tweezers for extracting bullets. And at the bottom of the box, most precious of all, the diary I kept.

Chapter One

‘Looks like a thunderstorm this afternoon. Maybe it’ll bring a change to the wind,’ I call down the main hatch.

Sandy is visible in the shadows below, kneading dough. After wedging the bowl into the sink, she sticks her head out of the hatch to see for herself.

‘About time.’ Satisfied by the presence of a few small cumulus clouds on the horizon astern, Sandy withdraws into the cool protection of the cabin, much like the molluscs she studies in her profession as a malacologist.

The persistent northeasterly winds and south-flowing Mozambique Current have forced us to zigzag northward within a narrow band of sea close to the coast. A gentle swell moves from the east, wafted along by unwavering winds. Those same winds flow smoothly across Arwen sails, cushioning her movement as her bow bubbles northward through the undulations. We are sailing along a zig or, to use the correct sailing term, a tack, diverging from the coast. This means we’re headed for the invisible river of south-flowing water that is the Mozambique Current. The black liquid-crystal numbers on the depth sounder show that there are 60 metres of water below our keel. Soon we’ll be entering that south-flowing treadmill. It’s time to turn onto the zag leg of our northward course, this time converging with the coast.

‘I’m about to tack,’ I call. ‘Hold on.’

Arwen’s wheel slides through my hand as her bow swings towards the land. I flick the ropes controlling the jib and staysail from their winches. The weathering sails flap and crack as they pass through the eye of the wind. With a heavy thlump the mainsail fills on the new tack while I wrap the ropes from the foresails around the winches on the port side and pull in the slack. The ropes creak under the tension as the sails fill with wind. Arwen heels slightly to port and a gurgle emanates from her bow as she gains speed. Stability returns to our buoyant home.

Silently I curse these persistent headwinds. Ever since we passed Richards Bay, 600 kilometres astern, we’ve had nothing but northeasterly winds from dead ahead and would have welcomed a westerly gale like the one that had so quickly steered us from our home port. For the past three days, sailing has been like living on a slow tedious pendulum as we tick tack our way towards the tropics and our final destination, the Bazaruto Archipelago.

Two hours later the saline ocean smell gives way to the yeasty aroma of baking bread wafting from below. Tammy sits next to me, scanning the distant Mozambican coastline. Her younger brother, Seth, is safely confined to the cockpit floor, playing with Lego. Through binoculars the low escarpment beyond the thin white line of distant breakers looks mauled, as if the sea has scratched away the green and exposed eroded red and orange wounds. Other than an occasional patch of listless smoke wafting from the low, hazy hills beyond, there is no sign of human life. The land looks exhausted and tired as it slouches towards the coast; very different to the velvet-green hills with their abundant scattering of homesteads and cattle along the coast near our home city of East London.

We knew Mozambique was fighting a civil, but we were assured this was far inland, over 400 kilometres to the north, near Gorongosa National Park. Tourist officials in Maputo had confirmed what we’d heard on the news and read in sailing magazines; that, in their words, ‘The coastline is secure.’ Maybe it is secure, but viewed from the sea it does not look at all inviting. Sandy calls up, ‘Who’s ready for a sarmie?’

Immediately Seth shouts, ‘Toothpaste!’ He turns five in a few days and is still struggling to get his tongue around consonants like f sounds. We know he means fish paste.

‘Peanut butter and honey … Er, no, peanut butter and Marmite … No, peanut butter and honey,’ calls Tammy. At eight years old she already knows enough of the abundance of worldly pleasures to be filled with indecision.

‘The usual,’ I call, knowing this will result in a pile of warm cheese sandwiches.

Soon the whole family is munching in the cockpit, joking over the memory of the bread we’d recently bought in Maputo. The golden billowing tops had looked so appetising in the shop. But when we turned the loaf over to slice while sailing across Maputo Bay, we discovered the underside encrusted with thumb-sized, barb-legged cockroaches that had presumably been feasting on the bottom of the baking pans before suddenly finding themselves entombed, like raisins, in dough. Astern, beyond Ponta Zavora with its white cylindrical lighthouse, which we struggled past in the morning, clouds are beginning to swell up; a hopeful sign of a pending change in the weather.

While we eat, those clouds puff into cauliflower-headed cumulus. In the process they morph and pillow, inspiring the children to visions of penguins, old men with beards and Seth’s favourite – toothy, open-mouthed crocodiles. The carved wooden version with a gaping red maw he’d bought with his wad of metical notes – the result of an exciting furtive money change in the Maputo market – adorns the shelf at the front of the cockpit.

An hour later an advancing cornice of dark cloud slides forward from above the cumulus and edges towards the sun. Soon distant rumbles warn of coming wind and rain. It’s time to prepare Arwen for action and that, hopefully, means lots of wind from astern.

Leaving our wind vane self-steering to guide Arwen, I drop into the cool of the cabin and tap the barometer fixed to the bulkhead. The thin black needle jerks counter-clockwise, confirming a change in weather. The depth sounder below the barometer blinks out the number 28. We’ve crossed the 30-metre depth contour and are heading into shallower water – my trigger to tack back out to sea. I scramble up the companionway stairs and look forward past the mast. The salient headland of Cabo de Corrientes is visible beyond Arwen’s pitching bows. This cape marks the spot where the coastline makes a definite bend to the north and, once past it, the sailing should be easier.

Cabo de Corrientes, or Cape of Currents, is a landmark of no visual distinction, but of great historical significance for East Africa. It is the most southerly point along the Swahili coast to which the early dhow traders dared sail, and therefore defines the southern extremity of Arab trade influence. To venture south past this cape risked sailing beyond the dependable trade winds of the tropics and exposed those wind-reliant sailors to the threat of being swept south by the strong Mozambique Current, into the region of fierce westerly gales that regularly brush the southern tip of the continent. It also defines the southern end of the Mozambique Channel. But for us this headland holds other significance. Once beyond this point we can justifiably claim to be in the tropics, and for me a long-cherished dream will finally be fulfilled.

‘Time to clear the decks,’ I call below. A salvo of rumbles, more felt than heard, warns that time is short before the storm arrives. ‘Hold on, we’re about to tack.’ Arwen’s bow swings seawards and steadies on the new course. I pull in the ropes controlling the sails and reset the wind vane. Sandy’s head appears in the companionway hatch as I step from the cockpit to the side deck.

‘I’m going to put a reef in the main to reduce its area and, just to be on the safe side, drop the staysail. That storm’s starting to look pretty threatening.’

While I clamber about the foredeck, lowering and unhitching the staysail before bundling it down the forward hatch into the children’s cabin, Sandy, sensing the urgency, moves about the cockpit collecting the accumulated detritus of books and toys. With the decks cleared, she shepherds the children below, leaving me alone on deck. I pull a reef into the mainsail, reducing its area and lowering the centre of power. With only the strong yankee sail fixed to the forward stay, and the smaller mainsail, Arwen moves gently through the water.

Sandy reappears at the hatch. ‘Make sure you’re clipped on,’ she warns as she passes me my oilskins and safety harness. ‘I’m going to stay below with the children.’ I pull on the oilskins and harness. It seems as if the wind is taking a deep breath.

I too find myself breathing deeply. The sails flop listlessly from side to side as we wait, becalmed. It seems too still. I look around and sniff the air in anticipation. Even though we are more than five kilometres offshore, there is the sudden, unmistakable smell of wood smoke. Without wind rippling the surface, the sea flattens to an undulating oily green sheen. It’s ominous and I stand up and glance astern, trying to find the source of the smoky smell. More thunder, almost overhead. A dark line on the sea surface indicates the approaching weather front and the imminent return of our motive force – wind.

‘At last!’ I yell to the approaching wind as I turn the wheel to align Arwen’s stern with the invisible wall of air rushing up from behind.

Neither I nor sleepy, lethargic Arwen are expecting it. Her sails fill with an explosive crack as she staggers and pivots in the water, momentarily stunned by the force that hits her. Another flat palm of wind scoops up a handful of spray and swats her onto her side as if she were a dinghy. Fortunately, the wind is still organising itself and these are just the outriders. In the lull that follows, Arwen lurches upright, but now she has only one thought in mind.

The next blast strikes, and 12 tons of steel come alive and flees downwind. With one hand, I cling to the wheel, caught off balance by the unexpected power, while with the other I reach for the mainsheet cleated behind me on the mainsheet traveller. I have to release it to spill some of the power of the wind so I can turn Arwen onto a safe broad-reach, sailing obliquely downwind.

The rigging hums and whistles as the wind strength alternates. Arwen’s bow pushes up a roar of white water that rushes past her gunwales. Another blast of wind hits, pivoting Arwen and flipping her onto her side, swinging her bow to face the wind. Suddenly released from the grip of the wind, she springs upright, the sails snapping and crackling like gunshots above my head. From below I can hear thumps and shouts, but there’s no time to concern myself with these as I turn her downwind. Arwen is alive like never before, careening along before the wind, heading north, parallel with the coast.

That coast, and all else, disappears as the heavens open. Stinging waterfalls of rain lash my face and drum into our sails before whipping off their trailing edges like streaming rivers. Screaming gust follows screaming gust, each more powerful than the last, doing its best to overpower us. Clearly this is no normal storm and exhilaration soon gives way to a mounting fear that I am losing control. The problem is the mainsail, which is simply too powerful for the yankee. The unbalanced twisting force between the sails overpowers the rudder and causes Arwen to pirouette on her keel, gyring her bows into the wind. Another gust hits the sails and Arwen responds by thundering forward, trying to climb her own bow wave, until the wheel suddenly goes limp in my hands as the rudder loses its grip on the water. Arwen pitches sideways again, pivoting into the eye of the wind. No longer filled, both sails stream like flags, flapping with such violence that the rigging thrums and vibrates, threatening to bring down the mast or shred the sails. We have to get the mainsail down.

I’m about to call for Sandy when the yankee sheet rips from its cleat. A stupid mistake; I should have double-cleated it. The sail flogs wildly, adding whip-like cracks to the scream of the wind and roar of rain. Like a shark shaking and ripping apart its prey, the clew of the sail disintegrates, tearing loose from its sheet and allowing the unrestrained ripped edge of the sail to flay about even more explosively than before. Now not just the rigging, but Arwen’s entire hull begins to vibrate like a giant orbital sander. With no balancing foresail, the main sail completely overwhelms the rudder. We are out of control.

Down below, Sandy and the kids have been tumbled about the cabin and the only safe place is the cabin floor. Using the settee cushions, Sandy wedges the children between the bunks before clawing her way up the companionway ladder. The noise and vibration below are terrifying. Scared that I have been washed overboard and that the cockpit will be empty, Sandy slides back the main hatch.

Her timing is perfect. ‘Get into your oilskins and safety harness and join me out here!’ I scream, even though I know I cannot be heard. Visibility has been reduced to no more than a few metres. The wind’s trying to churn the sea into waves, but the squalls rip the surface from the sea, sending billows of grey spume smoking into the air where it merges with the rain in a fuzzy turbulent interface between sea and sky. Torrential rain continues to sweep into the mainsail, flowing off the boom where it’s swirled away in the vortex beyond the sail. It’s impossible to look into the wind. The sea – or what little can be seen alongside Arwen – looks like whipped cream as giant raindrops thrash the surface to a froth.

Sudden, southwesterly gales are a common hazard of sailing in our home waters and Arwen was built to withstand, even relish, these conditions. In fact we’d timed our departure from East London to coincide with the passing of a cold front that delivered the desired strong westerlies that pushed us rapidly east to Durban before petering out as the front sped ahead and dissipated in the Indian Ocean. But what we are now experiencing is far more intense than any westerly gale.

Sandy throws out the tether of her safety harness and I clip it onto a free cleat. ‘We have to get that sail down,’ I yell superfluously, pointing to the shredded yankee Sandy nods and crawls along the side deck, sliding her safety line along the wire rope strung from bow to stern for that purpose. At the mast she releases the halyard and continues crawling to the bow to claw down the sail. At times she is completely obscured by the spume blown into the air as the wind tears at the surface of the sea.

I continue my struggle with the rudder, forcing Arwen onto a shuddering downwind course to spill wind from the mainsail. Between blasts I see Sandy winning her battle with the flailing Yankee, securing it to the side netting using the remains of the sheet.

Halfway down, the loose halyard of the Yankee catches on a cleat at the base of the mast. I lean forward to shout a warning to Sandy – an action that probably saves my life. Without warning, the wind switches through 180 degrees, taking the mainsail with it. The aluminium boom scythes over my head and with a thunderous explosion the sail fills on the opposite side of the yacht. Arwen’s hull lurches sideways from the impact but, miraculously, the rigging holds.

The change in wind direction brings a slight decrease in the strength of the gusts. Sandy takes over the steering while I crawl up to the mast and reef the mainsail to its smallest area. With less sail up, Arwen returns to her docile, obedient self. We roar along on a cushion of white water, heading safely out to sea. Over the next hour, the rain eases and the wind drops, allowing a steep swell to form.

The crisis over, Sandy and I sit together in the cockpit. The amount of energy unleashed during the storm has left us stunned and silent. Finally I suggest, ‘You’d better duck below and check if the children are okay.’ With a nod, she slides back the hatch and climbs into the main cabin. Soon she’s back in the cockpit, a smile on her face.

‘They’re fine. They’ve climbed onto our bunk and wedged themselves in. Both are fast asleep.’

In the fading light we huddle together, exhilarated by the spectacle of the storm still raging out to sea and glad to at last be making fast progress towards our destination. Above the invisible land to our left, the featureless stratus-clad sky lightens, suffuses and flares with an ever-brightening saffron glow. The sun suddenly appears from behind a hidden cloud; an orange disc dulled by the spume-filled air. The wind pushes Arwen onto an otherworldly stage; one in which all reference to horizon, sea or sky dissolves in a crepuscular glow with Arwen at the nexus and only the disc of the sun as reference. Eerie and portentous, the message is unmistakable: you may chase your dream, but don’t presume you are in control of your fate.

Happy sailing along the east coast of South Africa

Chapter Two

Arwen rumbles along, ploughing through the steep swell that has developed after the storm. The sepia-coloured world fades to grey and Arwen sails back onto a more familiar, less dramatic, stage. Out to sea, mountains of cumulus rim the horizon, sparking with lightning in the deepening dusk. The elements have stood tall and loud and we feel duly humbled. Sandy’s actions during the storm – suppressing the yankee sail and untying the sheets from the sail – remind me of the event that triggered this dream of sailing to a tropical island.

I was 13 years old, sitting cross-legged with my friends on the floor of the Seaman’s Institute in Port Elizabeth. We watched as leathery fingers formed a loop in a bristly three-strand hessian rope. The year was 1964.

‘Look!’ the man holding the rope said. ‘The snake comes up out of the pond, slithers behind the tree, and goes back down into the pond.’ The man – sailing around the world on his yacht, Sandefjord – jerked his hands apart. The strands forming the knot snapped together with a squeak.

‘Boys, that knot’s called a bowline and it’s the one knot you must know. Anyone know why?’

Hands shot up and shrill voices shouted, ‘Cos it won’t come loose!’

‘Let’s see.’ He tossed the free end to us while he grasped the loop with both hands and leaned back. We threw our combined weight behind the rope in a tug of war. ‘Whoa, whoa! You’re right. It won’t come loose, but many knots won’t come loose. A granny knot won’t come loose. But there’s another far more important reason. Look.’ He took the knot, the strands now fused and barely visible in what looked like a hairy nut, and bent it between his thumbs. The strands parted, and the knot fell apart. ‘Remember, boys, in an emergency it’s just as important to be able to untie a knot as it is to tie one. Otherwise you’ll have to cut loose and in doing so, destroy many useful ropes.’

Two years later that same man returned, this time with a documentary of Sandefjord’s successful cruise around the world. I watched in wonder as my parochial world widened to reveal unimagined places, and I dreamed the wild unrestrained dreams of a boy.

I was enthralled by scenes of Caribbean islands with white, palm-fringed beaches; the Panama Canal with its giant locks lifting huge ships tugged into place by odd-looking trains; scenes of snot-sneezing iguanas and blue-footed boobies in the Galapagos. The green, volcanic-ripped Marquesas Islands; Tahiti with its topless dancing women with gyrating grass-skirted bottoms that hinted at pleasures still unknown to me. And last of all, the shimmering, translucent underwater world of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. I was captivated. My world may have been geographically and economically constrained, but my dreams were not … One day I would own a yacht and sail to see those places for myself.

In the days following, while walking down Sydenham Road to school, I would look out across the width of Algoa Bay. On clear days, especially when the westerly gales blew, the dark arc of the bay trailed from the harbour off to distant Woody Cape in the east. I knew little of the art of sailing, but imagined myself rounding that distant cape, trusting the seamless oceanic link that led to all those mystical places. At that age, there was not much I could do to turn my dream to reality other than forage for lead sinkers lost by fishermen whenever I went snorkelling. I loved swimming and the sea so, with some determination, I gradually collected sinkers and melted them into an ever-growing block of lead that I was determined would one day form part of the keel of my yacht. And so my dreams coalesced into a reality manifested in a lump of lead that, two decades later, did indeed become part of Arwen’s keel.

Friday walks to school brought a particular joy. Passenger ships of the Castle Line docked in Port Elizabeth’s harbour en route to Durban from Southampton. In those days, before international airlines operated, this was the main link for mail and passengers between England and South Africa. My mom had arrived from England on one of those Castle Line ships in 1948, stepping ashore in Cape Town as a 22-year-old in search of a new life after serving in the Royal Navy during the Second World War.

Intuitively, I knew that for my mom these ships were an important physical link with her homeland; something confirmed every few years when one of my grandparents arrived for an extended visit. They brought with them chocolates and trinkets from that distant, mystical and, by all accounts, refined English-speaking land. As a result, I lived in curious suspension between my own homeland and this distant, soft, ephemeral country called England. Politically, although I knew this only in the vaguest way, this became the ‘us’ of the English-speaking United Party and the ‘them’ of the Afrikaans-speaking National Party. I did not know it, but I was a real-life soutie.

My first exposure to the latent tensions between the English and the Afrikaners occurred in 1960. The National Party was in power, but Queen Elizabeth was still head of state of the Union of South Africa – an intolerable situation for the republican-inclined Nationalists, who called a referendum amongst the white voters to test opinion over whether the Union of South Africa should become the Republic of South Africa. I was in Grade 5. My teacher, Mr Kruger, was clearly in favour of a republic and had no qualms about adding his political doctrine to the syllabus. The morning after the referendum, he announced, ‘Put up your hands all those whose parents voted for the Queen.’ About a quarter of the class, myself included, stuck up our hands. ‘Right,’ he said, pointing to those with raised hands, ‘come to the front.’ Alarmed, we shuffled forward. With obvious pleasure, Mr Kruger picked up his cane and imprinted the Union Jack onto our little rooinek-loving arses, just because our parents supported the Queen. It was a cruel, humiliating action that reinforced my prejudice and caused me to despise everything Afrikaans; an unwise decision that cast me, even at that young age, as an outsider in my own country.

These tensions were of course taking place in the wider, largely hidden context of racial separation. Even as I was receiving my introduction to the white man’s politics, the country had begun its devolution into racial chaos, the threat from the ‘rooi gevaar’, or Communist threat, ever present, and in 1969 I was conscripted into the army. My prejudices hardened and I knew I had to escape this growing madness. Stephen, a friend from school, served with me in the army and shared my views regarding the future of our country.

Before I could complete my degree in architecture I had to work in an office for one year. Stephen was already working fulltime, and we pooled our savings to buy a Fireball racing dinghy named Shortwave. The boyhood dream of sailing to strange and exotic places was one step closer, greatly promoted by the developing threat of political implosion and a love of sailing.

There is little that beats the exhilaration of sailing a Fireball in a brisk breeze. Pull in the sails and the yacht comes alive beneath you as it surges forward, riding up onto a plane, skimming and trembling across the water on a cushion of foam in an exhilarating headlong rush. You stretch and cantilever your body as far from the hull as you can, toes on the gunwale, counter-balancing the force of the wind in the sails, the power of the wind palpable as the spray stings and envelopes you. All seems in tenuous balance, on the very edge of control.

This is how our lives felt, almost out of control, yet delicately balanced; rushing headlong into the future driven by winds we did not understand. Behind the smiles and laughter, deep within the viscera of our emotions we felt trapped by an unsustainable political system and the manufactured obligation to fight a meaningless war. Discontent brewed in our minds.

A book titled The Greening of America, by Charles Reich, made a profound impact upon me and I shared Reich’s insights with Stephen. Reich concludes his book with these words:

‘We have been dulled and blinded to the injustice and ugliness of slums, but the new consciousness sees them as just that – injustice and ugliness – as if they had been there to see all along. We have all been persuaded that giant organizations are necessary, but it sees that they are absurd, as if the absurdity had always been obvious and apparent. We have all been induced to give up our dreams of adventure and romance in favor of the escalator of success, but it says that the escalator is a sham and the dream is real.’

The dream is real. These were powerful words that spoke to me and confirmed my desire, indeed confirmed the existential imperative to escape. Building a yacht with our own hands seemed the only practical way this could be achieved.

So, with my first pay cheque deposited in the bank, I took out a loan, Stephen and I pooled our money, and work on Arwen began. It took 10 agonising years of working nearly every weekend to complete her. The dream for Stephen and me had been to escape, but the reality soon became entrapment as Arwen took all our money and time. Yet somehow the dream held. Despite changing homes and workplaces, despite on-and-off romances, despite my marriage to Sandy and Tammy’s and Seth’s births, despite never having enough time or money and despite my moving to East London in search of better-paid work – forcing me to have to travel 600 kilometres each weekend to work on Arwen – in 1985 she was eventually launched in the Port Elizabeth harbour.

Sandy startles me from my reverie. ‘Would you like some coffee?’

While she makes her way below, I untie the torn yankee sail from the side deck where it had been secured during the storm and bundle it below to await repair. I pull the smaller yankee sail from the forward bunk where it has lain unused for five years, and attach it to the forestay. By nine o’clock the wind has dropped sufficiently for me to reset the full mainsail and hoist the inner staysail. During the night the westerly wind slowly dies away and backs to the east, forcing us to once again tack into the wind.

Soon after nightfall, the Ponta da Barra lighthouse at the entrance to the harbour of Imhambane, the only functioning lighthouse between Maputo and Beira, pops above the horizon. Throughout the night it guides us with a comforting triple flash every 10 seconds. Far out to sea, the storm feeds off the warm waters of the Mozambique Current, still glowing and sparking against the brightening sky. Sometime during the night we cross the Tropic of Capricorn and officially enter the tropics.

Daylight confirms the automatic self-steering rudder is gone, sheared off during the storm, and reveals steep, choppy waves from every quarter, bullying Arwen off her course and requiring constant correction of the rudder. As we crest the swells, a headland is visible off to port as a low, pale blue smudge on the horizon. Early mornings are seldom the best of times aboard a yacht and this morning is particularly trying. Dew coats every surface, dripping from the rigging and landing on the deck with loud plops. The seat of my oilskins slurps in the damp as I twist to lift the aft cabin hatch. ‘Welcome to the Tropics!’ I announce in my best pina-colada-tinged voice. Sandy groans and buries her head as cool air pours into the snug cabin.

A few hours later, all has changed. The sun blazes from a blue sky so deep and translucent you would think you were looking into eternity. The unpleasant swell of the earlier morning has smoothed, and the surface sparkles. Without doubt we’ve finally arrived in the tropics.

Back home in South Africa, Tammy’s friends have returned to school after the Easter holidays so, as part of the pact we’ve made to allow her to miss school, she sits in the shade of the mainsail, grumbling her way through the work her teacher has prepared in advance.

By mid-morning, the distant Ponta da Barra Falsa, the last prominent headland before we reach Cabo Sao Sebastiao at the southern entrance to Bazaruto Bay, lies directly to port. The wind remains fickle and eventually dies away, leaving us becalmed in a slow, sloppy swell. I drop the sails and start up our trusty Perkins diesel engine. Arwen motors over the undulating swells at a sedate five knots.

An hour later, Ponta da Barra Falsa is still abeam. We’ve barely moved. I sit in the cockpit looking for guidance in the East Africa Admiralty Sailing Directions. The entry for Ponta da Barra Falsa records a south-flowing current of one to two knots, and sometimes as much as four knots offshore from the Cape. Clearly we have chosen to arrive on a four-knot day and will make little progress until we move closer to the shore where, the Sailing Directions tantalisingly mention, there is sometimes a weak north-flowing counter-current.

I enjoy navigating and find satisfaction in using my handheld compass to take a bearing off whatever identifiable object happens to be within sight. To port, the defunct lighthouse on Ponta da Barra Falsa represents one such landmark, beyond our bow a conspicuous line of orange cliffs another. A simple calculation shows we will reach the islands soon after midnight.

Tomorrow, our friend Mike is flying to Magaruque Island, one of the archipelagos, to join us. Our timing will be perfect. High tide is around midday, allowing us to navigate the channel leading to the anchorage on a rising tide with the sun almost overhead, thus reducing reflection and making the deeper blue water of the channel visible. Tonight, once we are offshore and north of the islands I’ll heave-to, a sailing term for applying the brakes, and wait till daylight before approaching land. There is no need to rush.

While pondering over the charts, I’m distracted by a pinging sound from outside the hull: a school of common dolphins is surfing Arwen’s bow wave. I join Tammy and Seth at the pulpit rail where they peer into the blue depths as dolphins weave between the shimmering curtains of light from the sun’s rays.

Since we have time to spare, I turn off the Perkins, allowing Arwen to glide to a stop on a slow, heaving sky-blue mirror. Deprived of their fun, the dolphins head off, but the calm water is irresistible and in no time four piles of clothing lie on the deck as, shrieking with delight, we take turns bomb-dropping into the warm water.

After an hour of splashing about, we head north again, diesel thumping. I want to fix our exact position and the chart indicates the ideal marker for doing this. About six kilometres offshore from the orange escarpment, which the Sailing Directions identify as the Shivala Cliffs, lies a coral reef called Baxio Zambia. I aim Arwen’s bow towards the cliffs, intending to get a definite fix by passing over the reef, which is deep enough to pose no risk of our running aground. As we near the cliffs the depth sounder shows a steady depth of between 30 and 25 metres beneath our keel. Suddenly it drops to eight and the sea lightens to a pale blue. We are over the reef. I make a cross on our chart above the reef and write the time – 14:00 hrs. Back on deck I turn Arwen onto a new course that will take us away from the coast until, around about 02:00, we’ll heave-to and await daybreak.

With the wind-powered self-steering damaged beyond repair by the storm, Sandy and I have been taking turns steering Arwen. While Sandy takes the helm, I install our backup electric powered autopilot. We seldom use it, preferring to conserve electricity and use wind power. The backup has an inbuilt compass to keep Arwen on course, and takes an hour to fit. After all the parts are in place and the electricity connected, Sandy sits back, takes her hands off the wheel and the electric motor comes alive. It emits reassuring whirling sounds and jiggles the wheel back and forth as Arwen wanders either side of our course.

Back on deck, another landmark is coming into view. The Sailing Directions identify it as the 135-metre hill named Maxecane, the last landmark of any significance before we reach the islands. With the Shivala cliffs slowly disappearing astern, I take bearings on this hill and calculate that we still have a current of one knot flowing against us. Throughout the afternoon I continue to plot our dead-reckoning position every hour, adjusting the distance travelled to allow for this current. Slowly the line of crosses marked on the chart move north into deeper water, corresponding with the depths flashing on our depth sounder.

Freed from watch-keeping duty, Sandy prepares supper. Tomorrow, while safely anchored off Magaruque Island, we’re going to celebrate Seth’s fifth birthday and are looking forward to a slap-up meal, complete with cake, but tonight its mashed potatoes and sausages. The aroma of frying meat wafts from the main hatch and causes the children to chirp like hungry fledglings.

Sailing brings our family together in an especially intimate way seldom possible on land, where so many activities vie for attention. Tammy and Seth are robust, healthy, inquisitive kids. We try to raise them to question almost everything and they are taking full advantage of this freedom. It’s hard work and although they are able to entertain themselves, inevitably they challenge all attempts at discipline. Neither is particularly good about personal hygiene or cleaning up but what child is? This is our fourth, albeit longest and most adventurous ‘voyage’ on Arwen, so they are at home at sea. Our plan is to circumnavigate the world one day.

Sandy appears with steaming plates, but there’s no opportunity to sit back, cold beer in hand, savouring the moment and watching the sun disappear in a red blaze over Africa.

‘Everybody in the cockpit,’ I command. ‘Tammy, pack away that book. Seth, move up and give Tammy some room.’

‘Aww, Dad, I was here first.’

‘Come on. Move up!’

‘Move up, Seth,’ Tammy shouts.

‘Sit down, everyone.’ The captain’s word, at least in theory, is law. ‘Tammy, it’s your turn to give thanks.’

Tammy, in the breathless little voice she uses when speaking to God, says, ‘Thank you, God, for the dolphins … er … for keeping us safe … er … and thank you for this food. Amen.’ Mouths are filled and peace reigns, but only for a few minutes.

‘Mom! Seth’s taken my knife.’

‘It’s mine, and give me back my sausie.’

The sun drops, the sea turns slate grey and the comforting assurance of visibility fades with the day. Nights, with no reference other than from the stars, compass and depth sounder, always seem menacing to me. During the long hours of darkness one is truly adrift on a featureless sea. Satellite navigation is still in its infancy and beyond our budget. After dark, without lighthouses or other coastal lights as reference, there is no way of pinpointing one’s position other than to project a line forward on the chart, trusting we are actually sailing along that line.

After supper, the cockpit cleared and the kids asleep, the self-steering happily buzzing away, Sandy and I sit together chatting about our plans for the next day, glad we’ve almost reached our destination and will soon be able to relax in the safety of a sheltered anchorage. Inevitably we reminisce, chuckling how providence in the form of a broken hair-dryer brought us together.

Because I worked in an office nearby, Sandy had assumed I was the caretaker of the block of flats in Makanda where we both lived. I’d been designing at my drawing board when a harridan with wild wet hair burst in and demanded I immediately repair her electricity. Intrigued by her presumptuousness, I calmly went and turned on the circuit breaker in her flat, pointing out that the loose wire sticking out of her hairdryer probably had something to do with the problem. I was smitten and although Sandy, the all-action, scuba-diving marine biologist considered me an arty-farty dweep, I persevered and we soon discovered we had much in common.

With a kiss Sandy slips below to knead more dough for breakfast before getting some sleep. We usually sleep in the aft cabin, but to be available should I need any help during the night, she stretches out on the main salon bunk and is soon asleep. Up on deck drops of condensation dislodged by Arwen’s gentle rocking plink around me. We have a rule on board that, irrespective of conditions, safety harnesses must be worn when on deck at night. The risk of one of us falling overboard while the other sleeps is simply too horrible to contemplate. I clip myself to one of the spare cleats and spend some time tidying up the piles of damp rope lying about. This done, I clear a space on the port bench where I can lie sheltered from the wind while still keeping an eye on the compass. It slowly swings five degrees either side of our course as the autopilot whirs, guiding Arwen along the pencil line I’ve faithfully plotted on the chart.

Content that all’s well, I lie back and stare into the luminous sky. Directly overhead the masthead light wheels through the curved tail of Scorpio, which scurries like a real-life scorpion amongst the brilliant dust forming the arm of the Milky Way. Ahead, above Arwen’s bow, Arcturus, the brightest star visible from the northern hemisphere, shines in solitary splendour. Back in the cockpit the only light is from the soft glow of the compass binnacle and the red gleam of the depth sounder. The liquid-crystal screen has been flashing blankly for the past two hours, indicating that the instrument is no longer picking up the seabed and we are sailing away from the coast into deep water.

At two in the morning my dead reckoning places our position slightly north of the Bazaruto Archipelago and well out to sea. I turn Arwen through 90 degrees, leaving the sails set as they are. Arwen is hove-to, and will slowly drift sideways downwind at a speed of about half a knot. I climb below and, keeping my safety harness on, settle down on the bunk opposite Sandy, intending to climb up on deck every half-hour to check that there are no approaching ships. After 26 years I’ve finally achieved my dream of sailing to a tropical island. Feeling content, I relax – and that is a mistake.

Seth with his carved crocodile in Arwen’s cockpit in Maputo

Tammy climbing into Arwen’s cockpit

Chapter Three

A lurch, and the slightest of tremors passing through Arwen’s hull, wakes me.

Sandy feels it too. ‘David, we’re touching bottom!’

Instantly I’m on my feet, flinging off a foggy blanket of sleep as I lunge for the companionway ladder.

‘Start the motor!’ I shout.

As I step into the cockpit, Arwen lurches unnaturally upwards and I brace myself, knowing what is coming. With a tremendous reverberation, she drops to the seabed and heels violently over onto her port side. A wave breaks over the stern, sending a fan of sparkling phosphorescent spray into the mainsail. Water, glowing with phytoplankton, swirls along her decks and off the trailing edge of the boom.

The engine starts on the first turn of the key but I’m still disorientated and disbelieving. Arwen is hove-to and I waste valuable seconds uncleating the foresails. Sails free, I spin the wheel, slam the motor into forward gear and open the throttle, hoping to pivot Arwen on her keel to face the waves. The stern lurches skyward again, followed by another bone-jarring thump. A wave crashes over the side, causing Arwen to jolt sideways, throwing me off my feet into the side railings.

This time she stays on her side. A fearful whining vibration comes from the prop as it spins in air. We are aground.

The most important goal now is to stop us washing further ashore. We have to get an anchor out into deeper water. Crawling up to the bow along the steeply canted deck, I call to Sandy to bring the windlass handle. My fingers tear at the knot securing the plough anchor to the bow roller. The need to be fast and methodical conflicts with sheer disbelief. Obviously we are aground, but where, and how? In the darkness I can see phosphorescent-lit waves passing by, but it’s incomprehensible that we can be anywhere near land. Even though I fell asleep, we should have had kilometres of deep sea around us and hours of safe sailing time before we got anywhere near shallow water.

We carry three anchors on board Arwen. In anticipation of lots of anchoring around the islands, I’d replaced our small plough-type anchor with a heavier version while moored in Maputo. A smaller Danforth anchor and 100 metres of 20-millimetre diameter nylon rope are stowed beneath our bunk as an emergency backup.

It’s impossible to stand on the sloping deck so, while struggling to free the anchor, I’m forced to kneel in the cleft between the guardrail netting and the deck. Small waves jostle Arwen and suddenly another huge, glowing breaker looms out of the darkness and thuds into her midriff. The violent lurch flips me onto my back, wedging me between deck and netting. The phosphorescent firework spray slowly curves over Arwen’s deck and the wave washes back from what must be a shelving beach, sucking Arwen with it, momentarily pivoting her upright on her keel before flopping her onto her port side like a stranded fish.

In the distance I hear Sandy shouting, ‘Are you okay? You need anything?’

‘Yes. Can you bring the windlass handle?’

In near despair, I grapple with the anchor and chain and drop it over the bows. Sandy crawls up and hands me the windlass handle. I ask her to pull out all the chain while I jump over the side into chest-deep water and try to carry the anchor into deeper water.

The water is startlingly warm, like a bath. It does not take long to realise there’s no chance of my carrying the 60-pound anchor underwater as well as dragging the chain. Our only hope is going to be the small Danforth anchor and our 100-metre nylon line. I climb back on board and ask Sandy to fetch them while I clear the plough anchor and chain. With fiendish intent, the Danforth gets itself wedged in the timber framework below the bed and Sandy shouts for help. Turbo-charged by terror and desperation, we manage to wrest it free. Tammy and Seth huddle at the foot of the bed. We snatch a few moments to reassure them we will not allow them to get hurt, and instruct them to remain in the cabin.

Moving around Arwen has become an exercise in gymnastics. There are no level surfaces. Everything is canted at 45 degrees, forcing us to either crawl on our hands and knees or swing from overhead handholds like apes. We’re acutely aware of the urgency, but also of the overriding concern to not injure ourselves.

In the frenetic outpouring of physical and mental activity, strength drains from my body as I carry the anchor to the bows. In my head, a voice is telling me to just give up, give up, give up – Sandy and I can’t move 12 tons of steel against the power of the waves and gravity. I curse that voice. It’s distracting, draining me of vital energy, so I begin to talk to myself, my brain explaining to my body what I expect it to do. ‘Now, David, you need to get a large shackle from the locker. That is the locker next to the chart table, not the one below the spare bunk.’

It helps. My body responds like a robot, working calmly, methodically. My words soothe and slow me, helping to ward off panic while allowing Sandy to hear my thought process.

On deck, I tie the warp to the large eye-shaped shackle on the shank of the Danforth and drop the anchor over the bows. Arwen’s hull is still buoyed by the passing waves. I discover I can walk underwater while carrying the anchor and, between having to surface for breaths, manage to walk it out the full 100 metres of the warp into deeper water. I know it is spring tide; there had been just the faintest sliver of new moon the previous evening. If low tide is around midday, then it will now be approaching high tide. It’s the worst possible time to have run aground – not that there is ever a best.

Back in the bow, the winch handle in my hand, the hopeless voices rally. My body goes limp and I collapse on the deck, tears mingling with the spray. Arwen weighs 12 000 kilograms. Between us, Sandy and I weigh 140 kilograms. What hope is there?

The waves rush past in the dark, each still buoying Arwen’s hull, which hinges on the keel before dropping back onto the sand. Sandy sits beside me and puts her arms around my shoulders. ‘Don’t give up,’ she whispers, ‘There is still life in Arwen. There is always hope.’ Together we set about winching Arwen’s bow seaward in readiness for the next high tide.

Sandy braces herself on the deck with the warp belayed around her back, mountaineering style, while I lean back and forth on the winch handle with all my strength. The nylon line stretches until it is pencil thin and I’m terrified it will snap, but, millimetre by millimetre, the line reels in and Arwen slowly swings around till her bow points to the thin tinge of pink sky lighting the east.