6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

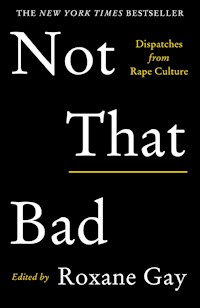

Edited and with an introduction by Roxane Gay, the New York Times bestselling and deeply beloved author of Bad Feminist and Hunger, this anthology of first-person essays tackles rape, assault, and harassment head-on. Vogue, 10 of the Most Anticipated Books of Spring 2018 Harper's Bazaar, 10 New Books to Add to Your Reading List in 2018 Elle, 21 Books We're Most Excited to Read in 2018 Boston Globe, 25 books we can't wait to read in 2018 Huffington Post, 60 Books We Can't Wait to Read in 2018 Buzzfeed, 33 Most Exciting New Books of 2018 In this valuable and timely anthology, cultural critic and bestselling author Roxane Gay collects original and previously published pieces that address what it means to live in a world where women have to measure the harassment, violence and aggression they face, and where sexual-abuse survivors are 'routinely second-guessed, blown off, discredited, denigrated, besmirched, belittled, patronized, mocked, shamed, gaslit, insulted, bullied' for speaking out. Highlighting the stories of well-known actors, writers and experts, as well as new voices being published for the first time, Not That Bad covers a wide range of topics and experiences, from an exploration of the rape epidemic embedded in the refugee crisis to first-person accounts of child molestation and street harrassment. Often deeply personal and always unflinchingly honest, this provocative collection both reflects the world we live in and offers a call to arms insisting that 'not that bad' must no longer be good enough.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

‘The diversity is striking – not only of perspectives, but approach, too. This is a book of testimonies, indignations, reproaches, meditations, written with poignancy and skill.’ Times Literary Supplement

‘an important book . . . observationally sharp, the writing often as vivid as bruises . . . the voices here are clear and compelling and crushing.’ Observer

‘Gay’s introduction moved me to tears, as did many of the pieces contributed by household names – Gabrielle Union, Ally Sheedy – but accounts from “regular” women moved me even more. Perhaps that’s the lesson we’re meant to take away from Not That Bad: we’re all “regular”. Shocking as they are, many of these stories will be familiar to us all – and we all deserve better.’ Glamour

‘The lauded social critic and provocateur curates a diverse and unvarnished collection of personal essays reckoning with the experiences and systemic dysfunction that produced #MeToo.’ O: The Oprah Magazine

‘Full of spectacular writing from both established and emerging voices.’ Elle

ALSO BY ROXANE GAY

Nonfiction

Bad FeministHunger

Fiction

AyitiAn Untamed StateDifficult Women

The names and identifying characteristics of some of the individuals featured throughout this book have been changed to protect their privacy while preserving the integrity of the authors’ stories.

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Allen & Unwin.

First published in the United States in 2018 by Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2019 by Allen & Unwin

Compilation and introduction copyright © 2018 by Roxane Gay

All essays not included in the Acknowledgments section on page 349 are copyright © 2018 by the author of the essay.

The moral right of the authors contained herein to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax: 020 7430 0916

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Internal design by Jamie Lynn Kerner

Paperback ISBN 978 1 91163 011 1

E-Book ISBN 978 1 76063 744 6

Printed in

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For every person who has been scarred by rape culture and survives, nonetheless.

Contents

Introduction

ROXANE GAY

Fragments

AUBREY HIRSCH

Slaughterhouse Island

JILL CHRISTMAN

& the Truth Is, I Have No Story

CLAIRE SCHWARTZ

The Luckiest MILF in Brooklyn

LYNN MELNICK

Spectator: My Family, My Rapist, and Mourning Online

BRANDON TAYLOR

The Sun

EMMA SMITH-STEVENS

Sixty-Three Days

AJ MCKENNA

Only the Lonely

LISA MECHAM

What I Told Myself

VANESSA MáRTIR

Stasis

ALLY SHEEDY

The Ways We Are Taught to Be a Girl

XTX

Floccinaucinihilipilification

SO MAYER

The Life Ruiner

NORA SALEM

All the Angry Women

LYZ LENZ

Good Girls

AMY JO BURNS

Utmost Resistance: Law and the Queer Woman or How I Sat in a Classroom and Listened to My Male Classmates Debate How to Define Force and Consent

V. L. SEEK

Bodies Against Borders

MICHELLE CHEN

Wiping the Stain Clean

GABRIELLE UNION

What We Didn’t Say

LIZ ROSEMA

I Said Yes

ANTHONY FRAME

Knowing Better

SAMHITA MUKHOPADHYAY

Not That Loud: Quiet Encounters with Rape Culture

MIRIAM ZOILA PéREZ

Why I Stopped

ZOë MEDEIROS

Picture Perfect

SHARISSE TRACEY

To Get Out from Under It

STACEY MAY FOWLES

Reaping What Rape Culture Sows: Live from the Killing Fields of Growing Up Female in America

ELISABETH FAIRFIELD STOKES

Invisible Light Waves

MEREDITH TALUSAN

Getting Home

NICOLE BOYCE

Why I Didn’t Say No

ELISSA BASSIST

Contributors

Acknowledgments

Introduction

WHEN I WAS TWELVE YEARS OLD, I WAS GANG-RAPED IN the woods behind my neighborhood by a group of boys with the dangerous intentions of bad men. It was a terrible, life-changing experience. Before that, I had been naive, sheltered. I believed people were inherently good and that the meek should inherit. I was faithful and believed in God. And then I didn’t. I was broken. I was changed. I will never know who I would have been had I not become the girl in the woods.

As I got older, I met countless women who had endured all manner of violence, harassment, sexual assault, and rape. I heard their painful stories and started to think, What I went through was bad, but it wasn’t that bad. Most of my scars have faded. I have learned to live with my trauma. Those boys killed the girl I was, but they didn’t kill all of me. They didn’t hold a gun to my head or a blade to my throat and threaten my life. I survived. I taught myself to be grateful I survived even if survival didn’t look like much.

It was comforting, perhaps, to tell myself that what I went through “wasn’t that bad.” Allowing myself to believe that being gang-raped wasn’t “that bad” allowed me to break down my trauma into something more manageable, into something I could carry with me instead of allowing the magnitude of it to destroy me.

But, in the long run, diminishing my experience hurt me far more than it helped. I created an unrealistic measure for what was acceptable in how I was treated in relationships, in friendships, in random encounters with strangers. That is to say that if I even had a bar for how I deserved to be treated, that bar was so low it was buried far belowground. If being gang-raped wasn’t that bad, then it wasn’t at all that bad being shoved or having my arm grabbed so hard it left five bruises in the form of fingerprints or being catcalled for having large breasts or having a hand shoved down my pants or being told I should be grateful for romantic attention because I wasn’t good enough and on and on. Everything was terrible but none of it was that bad. The list of ways I allowed myself to be treated badly grew into something I could no longer carry, not at all.

Buying into the notion of not that bad made me incredibly hard on myself for not “getting over it” fast enough as the years passed and I was still carrying so much hurt, so many memories. Buying into this notion made me numb to bad experiences that weren’t as bad as the worst stories I heard. For years, I fostered wildly unrealistic expectations of the kinds of experiences worthy of suffering until very little was worthy of suffering. The surfaces of my empathy became calloused.

I don’t know when this changed, when I began realizing that all the encounters people have with sexual violence are, indeed, that bad. I didn’t have a grand epiphany. I finally reconciled my own past enough to realize that what I had endured was that bad, that what anyone has suffered is that bad. I finally met enough people, mostly women, who also believed that the terrible things they endured weren’t that bad when clearly those experiences were indeed that bad. I saw what calloused empathy looked like in people who had every right to wear their wounds openly and hated the sight of it.

When I first came up with the idea for this anthology, I wanted to assemble a collection of essays about rape culture—some reportage, some personal essays, writing that engaged with the idea of rape culture, what it means to live in a world where the phrase “rape culture” exists. I was interested in the discourse around rape culture because the phrase is used often, but rarely do people engage with what it actually means. What is it like to live in a culture where it often seems like it is a question of when, not if, a woman will encounter some kind of sexual violence? What is it like for men to navigate this culture whether they are indifferent to rape culture or working to end it or contributing to it in ways significant or small?

This anthology became something far different from what I originally intended. As I started receiving submissions, I was stunned by how much testimony writers offered. There were hundreds and hundreds of stories from people all along the gender spectrum, giving voice to how they have suffered, in one way or another, from sexual violence, or how they have been affected by intimate relationships with people who have experienced sexual violence. I realized that my original intentions for this anthology had to give way to what the book so clearly needed to be—a place for people to give voice to their experiences, a place for people to share how bad this all is, a place for people to identify the ways they have been marked by rape culture.

As of this writing, something in this deeply fractured culture is, I hope, changing. More people are beginning to realize just how bad things really are. Harvey Weinstein has fallen from grace, named by a number of women, as a perpetrator of sexual violence. His crimes have been laid bare. His victims are, at least to some extent, vindicated. Women and men are coming forward and naming sexual harassers or worse in publishing, journalism, the tech world. Women and men are saying, “This is how bad it actually is.” For once, perpetrators of sexual violence are facing consequences. Powerful men are losing their jobs and their access to circumstances where they can exploit the vulnerable.

This is a moment that will, hopefully, become a movement. These essays will, hopefully, contribute to that movement in a meaningful way. The voices shared here are voices that matter and demand to be heard.

NOT THAT BAD

Fragments

AUBREY HIRSCH

HE SAYS, “YOU SHOULDN’T WAVE THOSE AROUND LIKE that.”

You’re in the campus dining hall with your friend James. You’ve just popped a rust-colored birth control pill out of its slot in the rubbery blue envelope.

You say, “I wasn’t. I was just taking one.”

He says, “You should take them in your room. By yourself. Privately.”

“I have to take them with food,” you say, “or they make my stomach hurt.” It’s been that way since you were fifteen and first started taking them. That was years before you actually have sex and, even when you do, you are so afraid of getting pregnant accidentally that you don’t let a man come inside you until after you’re married.

You take them because your period is a terrifying beast. The hormones gallop through your veins. You wake up in the middle of the night, twisting; your stomach lurches, your intestines heave. The pills help. You don’t like taking them every day, though. Even the smell of the blue rubber envelope makes you a little queasy when you, dutifully, pull them out of your purse at the same time every afternoon to sedate the beast inside.

He says, “Still, you shouldn’t let everyone see. You don’t want some guy to see you taking those and think he can take advantage of you and there will be no consequences.”

You put the pill on the back of your tongue and the envelope back in your bag. James watches as you bring your water glass to your lips. You swallow. Hard.

IF RAPE CULTURE HAD A FLAG, IT WOULD BE ONE OF THOSE BOOB INSPECTOR T-shirts.

If rape culture had its own cuisine, it would be all this shit you have to swallow.

If rape culture had a downtown, it would smell like Axe body spray and that perfume they put on tampons to make your vagina smell like laundry detergent.

If rape culture had an official language, it would be locker-room jokes and an awkward laugh track. Rape culture speaks in every tongue.

If rape culture had a national sport, it would be . . . well . . . something with balls, for sure.

_________________

YOU DRINK TOO MUCH AT THE PARTY BECAUSE IT’S COLLEGE and you’re always drinking too much. The party is terribly generic with beer pong and a bass-heavy sound track. Everyone is drinking foamy beer out of red Solo cups. You think there might even be a black light somewhere.

Daniel knows you don’t drink beer, so he has brought you a bottle of cheap vodka, which you drink mixed with even cheaper orange juice.

You flit around for a while, talking to one group of people, then another. A boy in the kitchen—a baseball player—takes his dick out to show everyone how big it is. It is, in fact, very big.

The last thing you remember is lying down on the couch. Just to close my eyes, you think, just for a minute.

When you wake up, you are in a bed in an upstairs bedroom you have never seen. Daniel is in the bed next to you. Your clothes are on, but your shoes are off.

“Hey,” you say, pressing into your temples. Maybe if you press them hard enough the pounding will stop.

“You fell asleep,” he says, before you even ask. “I carried you up here.”

You say, “You carried me?”

“Yeah. I didn’t want to just leave you down there with all those dudes, passed out on the couch like bait or something.”

“Did you take my shoes off?”

“Yeah. So you could sleep.”

Your mouth feels dry. Everything is blurry. You rub your eyes and take in a breath so you can thank Daniel when he says, “I took your contacts out, too.”

You don’t know where your gratitude goes, but suddenly it’s gone.

THESE STORIES AREN’T WORTH TELLING. THERE’S NO ARC TO them, no dramatic climax. There’s nothing at stake, not really. You imagine your listener, leaning in, “And then what happened?” And you have to say, “Nothing. That’s the whole story.” “Oh,” she says, her mouth a firm line.

These are little bits of things that happened, or things you think about. They’re light on tension, you know that. There’s no real peril. There’s no resolution.

Still, they stick with you. You think about them even after they’re over, sometimes for a long time. Sometimes for a very long time. That’s how you know they’re important somehow. It’s why you can recall the smell of that party, even many years after the smell of your grandfather’s cologne has faded from your memory.

WHEN YOU BECOME A WRITING INSTRUCTOR, EVENTUALLY, you end up with stories about rape stories.

The first story is a rape story on purpose. A student hands it in for a fiction assignment in the composition class you are teaching. In it, the hero finds his petite, brunette English teacher alone in a church. He pulls out a 24k gold–plated gun with a pearl handle, holds it to her head, and rapes her, bending her over the back of a pew. When he’s finished, he drives off in a convertible and leaves a bag of money at the police station to avoid arrest.

You are the petite, brunette English teacher. You’re only twenty-two, just a few years older than this student who now sits in your office with his hat pulled down over his eyes. You’re too timid to call him out on this threatening misogynistic bullshit. What if you’re wrong? What if he complains to your boss? What if he gives you a low score on your teaching evaluations? Instead, you critique the story, which isn’t hard: It’s a horrible story. “The hero is unlikable and the ending is ludicrous.” You say all this to your student as he smirks beside you. “And look here,” you say, “a slip in verb tense; here, a comma splice.”

In the second rape story, the hero meets a girl at a party. She’s beautiful, drunk, glassy-eyed, and nearly incoherent. When she’s no longer able to walk, the hero, who hasn’t had anything to drink, carries her outside, to the beach. He strips off her clothes and has sex with her while she makes soft moaning sounds. Then he dresses her again and lies beside her on the sand.

“The tone is a bit confusing,” you tell your student when he comes in for a conference. “It seems romantic, almost. Are we supposed to feel sympathy for this character, even as he’s raping her?”

The student looks taken aback, surprised. “He’s not raping her. They’re having sex.”

You point out all of the evidence that he is, in fact, raping her. She’s clearly very drunk. She can’t even walk by herself. She never takes any agency, just lies there while it’s happening.

The student cuts you off. “This is, like, based off me hooking up with my girlfriend for the first time.”

It hadn’t occurred to you that the student might not have realized he was writing a rape story.

“All I can say,” you say, “is that a lot of people are going to read this as rape.”

“But it isn’t,” he says, weakly, sounding more like he’s trying to convince himself than you. “It wasn’t.”

The third story comes to you in a creative nonfiction class. The narrator gets very drunk at a party. She kisses one guy and another kisses her. She runs away and bumps into an acquaintance, who she barely recognizes through a haze of cheap beer. He is aggressive, putting his penis inside of her while she tries to stammer, “wait, wait.”

You start the workshop by asking your students to give a quick summary of the piece. Someone offers, “It’s about a girl who goes to a party and gets drunk and hooks up with a bunch of dudes.”

Interesting. “Does anyone have anything to add or a different read?” The students shake their heads. “Well,” you offer, “I think this first part is a hookup, and the second part, maybe a misunderstanding, but I read this last section pretty straightforwardly as being assault.”

All of the students look down, rereading the last section. Some of them tilt their heads, as if to say, Hm. The essay never uses the word rape, but it does say “wrong.” It says “wasted” and “sick” and “dizzy” and “vomit.” It says “ignore.” How is it possible they haven’t seen this? How is it possible they are learning about consent from their teacher?

The author of the essay is forbidden to speak by the rules of the workshop, but you study her as she takes notes in silence. Did she know? you wonder. Does she know now?

YOU RECOGNIZE THE TENSION BETWEEN “I AM A BODY” AND “I have a body,” but you are unable to resolve it. “Have” implies that this body is just a possession, that it can be lost or thrown away. That you can do without it. It implies, perhaps, that someone else could have your body and that your body would be not your own. That it would belong to another.

That doesn’t feel quite right.

But “am” doesn’t seem right either. To “be” a body suggests that you are only a body. You are meat and some blood. You are hard bones and flexing cartilage. You are tangled veins and skin. Is that all, though?

You stand in front of the full-length mirror on your closet door and take inventory. Here are your knees; there are two of them. Two elbows. A chin. A torso with breasts that are heavy with milk. Feet. Hands. Knuckles. Two earlobes. Ten toenails. Several dime-sized bruises. Thousands and thousands of hairs.

There are things you can’t see, but you know they’re there. Two lungs. A liver. The stacked cups of your backbone. Your heart you saw once on an ultrasound machine. Your womb you’ve seen four times, but never when it was empty. Nerves. Ball joints. The intricate pleating of your brain.

It is a long list, but also, it is not so long. Looking at it now, you wonder, isn’t there more to you than that?

SOMETIMES PEOPLE TELL YOU THAT YOU’RE LUCKY THAT YOU have sons so they won’t have to deal with all this crap.

It’s true that your kids, by virtue of both being boys, will be in a privileged position, but the idea that they “won’t have to deal” with rape culture makes you shudder. You very much want them to “deal with” rape culture the way one “deals with” a cockroach problem.

Sometimes you think about what you’ll tell them and come up surprisingly blank. It’s the words that fail you, not the ideas. The ideas are there.

Though you aren’t sure exactly what you’ll say, these are the things you want them to know:

It’s not okay to hit the girl you like. And it’s not okay to hit the girl you love.

The world around you tells women that they should always nod politely no matter what they’re feeling inside. Don’t ever take a polite nod for an answer. Wait for her to yell it: “Yes!”

Not everyone gets sex when they want it. Not everyone gets love when they want it. This is true for men and women. A relationship is not your reward for being a nice guy, no matter what the movies tell you.

Birth control is your job, too.

Don’t ever use an insult for a woman that you wouldn’t use for a man. Say “jerk” or “shithead” or “asshole.” Don’t say “bitch” or “whore” or “slut.” If you say “asshole,” you’re criticizing her parking skills. If you say “bitch,” you’re criticizing her gender.

Here are some phrases you will need to know. Practice them in the mirror until they come as easy as songs you know by heart: “Do you want to?” “That’s not funny, man.” “Does that feel good?” “I like you, but I think we’re both a little drunk. Here’s my number. Let’s get together another time.”

YOUR COUSIN TEXTS YOU OUT OF THE BLUE TO SAY, “I JUST GOT raped at the bank.”

“Oh my God,” you respond. “Are you okay?” Your brain goes turbo. You are trying to imagine which hospital she’s at, if she’s likely to press charges, why she’s reaching out to you and what you can possibly do to make this any less devastating.

The flashing ellipsis appears on your phone to signal that she’s typing. Then it turns to words that you struggle to focus on: “Yeah. I deposited my check in the wrong account so I’ve been overspending on my debit card. I got like $175 in fees.”

You watch for the ellipsis, but it doesn’t appear. After a moment you realize this is the whole story. By “I got raped” she meant “I got charged bank fees for overdrawing my account.”

You stare at your keyboard for a while, with its letters and exclamation points and frozen-faced emojis, and then you put your phone away. You can’t think of a single thing to say.

_________________

JORDANA HAS INVENTED A NEW KIND OF RAPE-PREVENTION underwear. If she orders a batch of five thousand pairs, she can manufacture them for $2.25 per pair and wholesale them for $4.00 per pair. If she orders ten thousand pairs, she can manufacture them for $1.90 per pair and wholesale them for $3.50. Given these figures, and assuming no import taxes, how will she get the rapists to wear them?

Marc leaves work at 6:25 every evening. Moving at a steady 6 miles per hour, he walks eleven blocks north, three blocks west, and one block south to get to his apartment. On his way home, he passes the diner where Gina works. When she works the afternoon swing shift, she leaves work just before Marc passes by. She walks eight blocks north at an average speed of 5.5 miles per hour. Now that it’s wintertime and starting to get dark, how far behind Gina should Marc stay so that she won’t be afraid that he’s coming to attack her?

Carla is editing her online dating profile. When she adds the word cheerleader, her message requests go up by 11 percent. When she changes her body type from “average” to “thin,” her message requests increase by 42 percent. When she lists “feminism” as an interest, her message requests decrease by 86 percent and the number of rape threats she receives triples. Assuming she goes on an average of three dates per month, how many hours will she need to spend with any given man before she feels comfortable giving him her home address?

A child is raped in Montana. The rapist is thirty-one; the child is fifteen. The age of consent is sixteen. The punishment for statutory rape in Montana is two to one hundred years in prison and a fine of up to $50,000. If, however, the rapist is only sentenced to thirty days in jail and no fine at all, how much older than her chronological age must the child have been behaving when she seduced him?

THIS IS YOUR NEW THING: WHEN A MAN YELLS AT YOU ON THE street, you yell back. You are tired of pretending you can’t hear these men. You are tired of gluing your eyes to the sidewalk in shame. You are tired of taking it, of treating it like a tax you must pay for the privilege of being a woman in public spaces.

You think, perhaps foolishly, that you can explain your feelings to these men and they will listen.

You wear your resolve like armor and it doesn’t take long for you to get a chance to put your plan into action. You are leaving the store, a plastic bag of groceries dangling from each hand, when a man walking behind you says, “Hey hey hey! You are beautiful.”

You stop walking and he passes you. It’s now or never.

You say, “Can I talk to you for a second?”

He stops to face you, about three feet away.

“Why did you say that to me?”

Instead of answering, he just tries his line again: “Hey beautiful girl!”

“Can I tell you something?”

He doesn’t answer, but he doesn’t move away. He seems confused, like when you push a floor button on an elevator and the doors don’t close, so you just keep pressing it. Why aren’t you shutting up? This isn’t what’s supposed to happen.

You say, “When you say that to me, I don’t feel flattered. I don’t even feel angry, honestly. I feel afraid. Did you know that?”

“Why? Why are you afraid? Afraid of me?”

“Yes,” you say. “When men like you yell stuff at me on the street, I am afraid that you will hurt me.”

“Oh, I’m scary. Is that what you’re saying?” Now, he moves. He takes a big step toward you and, damn it, you flinch.

You say, “Yes,” trying to plate the word in steel but it crumbles in your larynx like tinfoil. You start walking to your car.

He follows you the whole way, shouting, “Now I’m scaring you, huh? Now you’re afraid of me!”

He’s right. He is scaring you. You are afraid. But there’s something new, too. Before this, you really thought maybe these guys just didn’t know how their comments made people feel. You thought maybe they were trying to be nice. But now you know the truth—they know it makes you feel frightened. They like it.

There’s still fear, yes, but now there’s anger, too. So much anger that it boxes out some of your fear. The next time you yell back to the man yelling at you, it’s easier. And the time after that is easier still.

Now the responses roll off your tongue like perfect round stones. You’ve worried them in your mind and in your mouth until they are smooth as glass: “Why would you say that to me?” “That is an offensive thing to say.” “It’s hurtful to talk to women like that.” “You should never say that again.”

Your prize for all this effort is a small thing, but you cherish it. It is the astonishment on your harasser’s face. Sometimes he even mutters a flimsy “Sorry” before he hurries away from you. He doesn’t want a conversation. He’s not shouting at you as a method of engagement; he’s just testing something out. He needs to fumble around for his power in the dark, like a totem he carries in his pocket. He wants to make sure it’s still there.

Next time, you tell yourself when it’s done, this man won’t shout so readily. Next time he will see the woman coming, open his mouth to speak, and for one second, one perfect second, he will be afraid of her.

Slaughterhouse Island

JILL CHRISTMAN

THE THING ABOUT TELLING THIS STORY EVEN THIRTY years later is that even though I know where the culpability rests—firmly—I have trouble soaking off the most dogged shame. I am scraping away the last of the sticky residue with my thumbnail.

Yes, I did some stupid things. We all do. But now I know we’re allowed to be kids who mask our gut-deep insecurities with vanity. We get to wear crop tops and tight jeans with a ribbon of lace for a belt and high-heeled boots. We get to check ourselves ten times in the dorm-room mirror, necks craning to see how fat our skinny little asses look from the back, and we even get to guzzle sweet drinks and swallow harmless-looking tabs we hope might make us feel better or dance faster or look prettier or just forget. We get to want something to come easy for a change. We get to make every choice on that daily life scale from forward-thinking to utter self-sabotage.

And we still don’t deserve to be raped. Not ever.

How did we ever get to a place where victim blaming was wedged so far into our brains? Turn this around, I think to myself, scraping with my thumbnail. Turn this around. What would Kurt have had to do for me to feel justified in raping him?

There’s no answer to that question.

I want to fold time. I want to walk into that Italian restaurant in Eugene, Oregon, where my eighteen-year-old self is having her first awkward date with Kurt, take her by the hand, and ask her to join me in the bathroom. Instead of letting her throw up the four bites of creamy pasta she ate for dinner—which I know is all she can really think about as she watches Kurt’s pointy teeth flash in the candlelight—I want to pull her around the corner, hurry down the hall in the opposite direction, and make for the exit.

We’ll leave together, I’ll walk her back to the dorm, and we’ll have a talk. I’ll save her, somehow, from what’s going to happen to us next, even though, sweet girl, I know it’s not your fault. None of this was ever your fault. Do you hear me?

Not. Your. Fault.

But from here, back in the future, I can only watch.

“YOU DRIVE A PORSCHE”—RHYMING WITH BORSCHT WITH-out the final “t”—I’d said, after I’d lowered myself down onto the soft leather of Kurt’s sleek silver car, hoping my friends on the second floor of the freshman dorm were peeking from behind the curtains. He’d leaned in toward me, breath too minty, already-thinning dark hair glinting with product in the spring sunshine, and moved his large hand from the gearshift to my thigh. I think he was trying to look sexy but managed instead to look maniacal.

“Por-shhhhha,” he said. “People who don’t have Por-shas call them Porsches. People who drive Por-shas call them Por-shas.”

I moved my knee a fraction, the tiniest of objections, and said, “Well, I don’t have a Porsche, so I’d better call it a Porsche.”

“You’re with me now,” he said, thin lips curling into a smile. “Now you can call this car a Por-sha.”

I hadn’t had a date like this before—what I imagined to be a real college date, during which Kurt picked up, moved, or lifted everything that might need picking up, moving, or lifting: the door to the Por-sha, my chair at the table, my body by the arm when another man came too close, and of course, the check. We went to a real sit-down Italian restaurant with white linen tablecloths, candles, and dim lighting, where we talked about the extensive time he and I both spent at the gym on the edge of campus: me in aerobics classes burning away any calories I’d consumed in moments of weakness, and him lifting and slamming giant iron discs in the testosterone soup that was the main gym.

We were both too tan, this being the era of ten tans for twenty dollars in the warm booths on the campus strip. I was in my first year in the Honors College, reading Darwin and Shakespeare and Austen, having my mind blown by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and theories about sexual selection and how the universe began. Kurt was in business, a supersenior—the first I’d heard such a moniker, though it didn’t take me long to figure out that the “super” didn’t mean anything good.

Since we had nothing else to discuss, the conversation turned to tanning. I told him how I always fell asleep under the lights, the humming blue womb offering respite from the gray Eugene winter—although I’m sure I wouldn’t have said “womb,” not that night—and Kurt’s teeth glowed in the dim candlelight like something out of a horror movie.

AFTER DINNER, KURT TOOK ME BACK TO AN APARTMENT THAT looked like nobody lived there, gave me something to drink, and led me through the living room with its black leather couch and glass coffee table into his bedroom. Closing the door behind him, he showed me the hand weights he kept in a line by the wall, like shoes, and then pushed me toward a desk. I remember his hands always on my body, and even before he pulled the mirror and the razor blade out of the center drawer, I was thinking, This isn’t good.

Kurt reached into the pocket of his coat and pulled out a paper packet—druggie origami—tapping two snowy piles onto the glass. I watched him chopping and scraping, wincing a bit at the sound, a fork on china, nails on a chalkboard, a warning alarm I would fail to heed. Down to the roots of my nerve fibers, I knew the thing to do was get out, but this was to be a night of many college firsts: first restaurant date, first ride in a Porsche, first blow. Kurt rolled a crisp green bill from his wallet and showed me what to do.

It burned. And then? Not much. The coke had done nothing more than make my eyes feel really, really wide open. I would be hyperalert for what came next.

Which was also almost nothing. He kissed me, and as he did, he pulled me away from the desk and down onto the bed. He was the world’s worst kisser, all probing tongue, like a sea slug trying to move down my throat. I was repulsed, but saved (I know now) by the coke: Kurt couldn’t get it up. He rolled against me, and through the thin fabric of his dress khakis, I could feel him against my thigh, soft as a dinner roll.

George Michael sang through the speakers. Rather than pursue what he must have known from experience was a losing game, Kurt sprang from the bed, as if he’d planned it that way, and went to the stereo to turn it up. I will be your father figure. Thirty minutes later, when I asked for a ride back to the dorm, he gave me one without much of a fight. In the Por-sha.

The next day, apparently having had more fun than I had, Kurt called to ask if I’d go with him to Shasta Lake, an annual Memorial Day fraternity tradition at the University of Oregon: at least a hundred rented houseboats, each carrying eight or so couples, kegs tapped and flowing, red Solo cups bobbing in the water like buoys.

Imagine the drinking and the drugs. Imagine the sleeplessness and the unfinished brains. Imagine the heat, the dehydration, and the food packed by the boy-men hosting this nightmare. Imagine that nobody on the whole boat had the sense to bring sunscreen. Imagine the depth of seething, unmet need—and then imagine the depth of the water.

Imagine, too, that I’d already made plans to go with a friend from my dorm, a guy named Jeff, who had pledged a fraternity the previous fall. Stretched to his full height, Jeff reached only to my nose, but he was clever and made me laugh, so when he’d quite casually offered to bring me along to Shasta, I’d agreed.

But a real invitation from a real date with a real car and a real apartment with real furniture seemed like just the kick in status I needed to go from full-scholarship hippie kid with Beatles posters and batik bedspreads stapled to the walls of her dorm room to . . . to what?

What did I want to be? Part of the system my liberal artist parents had always rejected? Noticed? Accepted? Desired?

I didn’t even like Kurt: he represented everything I’d been taught to distrust in the world, a privileged fuck from the burbs who thought anything could be his for the right price, including me.