Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: 404 Ink

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Inklings

- Sprache: Englisch

Grief is all around us. Even at the heart of the brightly coloured, vividly characterised, joyful films of Studio Ghibli, they are wracked with loss – of innocence and love, of the world itself and our connection to it. Whether facing the realities of death, the small and continual losses we encounter through our daily lives, or the anticipatory grief of the environment's ongoing decline, each has a distinct presence in these beloved films, with their own lesson to hold close in our lives, and comfort to be found. Now Go enters the emotional waters to interrogate not only how Studio Ghibli navigates grief, but how that informs our own understanding of its manifold faces. Touching on some of the cornerstone films and characters — from My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away and beyond — and their intersections with his own life, the broader spectrum of loss, and how we can move forward, Smith invites us to consider how these beacons of joy offer us a winking light in the darkness. (Please note this title is unaffiliated with Studio Ghibli.)

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 98

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Now Go

Published by 404 Ink Limited

www.404Ink.com

@404Ink

All rights reserved © Karl Thomas Smith, 2022.

The right of Karl Thomas Smith to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

All trademarks, illustrations, quotations, company names, registered names, products, characters, used or cited in this book are the property of their respective owners and are used in this book for identification purposes only. This book has not been licensed, approved, sponsored, or endorsed by any person or entity and has no connection to Studio Ghibli.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining the written permission of the rights owner, except for the use of brief quotations in reviews.

Please note: Some references include URLs which may change or be unavailable after publication of this book. All references within endnotes were accessible and accurate as of October 2022 but may experience link rot from there on in.

Editing & proofreading: Heather McDaid

Typesetting: Laura Jones

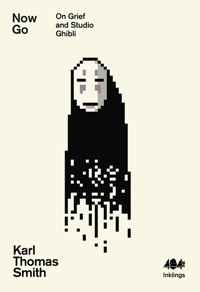

Cover design: Luke Bird

Co-founders and publishers of 404 Ink:

Heather McDaid & Laura Jones

Print ISBN: 978-1-912489-58-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-912489-59-6

Now Go

On Grief and Studio Ghibli

Karl Thomas Smith

Contents

Spoiler Notes

Introduction: A winking light in the darkness

Chapter 1: Grief has No-Face

Chapter 2: Our neighbour, certain death

Chapter 3: The squandered gift

Chapter 4: The animated anthropocene

Chapter 5: Grief is a myth, and myths are real

Epilogue

References

Acknowledgements

About the author

About the Inklings series

Spoiler Notes

Now Go touches on many of the films of Studio Ghibli in various levels of detail, and spoilers large and small include:

Grave of the Fireflies

Kiki’s Delivery Service

My Neighbor Totoro

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea

Princes Mononoke

Spirited Away

Introduction: A winking light in the darkness

What do you think of when you hear “Studio Ghibli”?

Elegant, exquisitely translucent, watercolour skies? Sunsets that effortlessly turn from the lightest pastel hues to the most striking halogen glows as they effervesce? The pang of childhood nostalgia and a beguiling sense of wonderment at the beauty of our natural world? Perhaps a style of cloud so unique and so recognisable that it rivals even the best that the real world has to offer – or even a vision of Totoro himself; the culturally ubiquitous gentle giant which has become Ghibli’s honorary mascot.

All of these are good answers. Right answers, even. But they are all just a small part of the picture. When I hear “Studio Ghibli”, I think of all these things. But there is also something else: not so much a thought as a feeling. Something not rendered in those frames, not contained in those forms and colours, but illuminated by them. You see, I did not grow up with the films of Studio Ghibli. Not in the traditional sense, at least. But I wish that I had.

*

I was twelve when the English-language dub of Spirited Away was first released, winning the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. A short time later, my grandfather – very much a presence in my life until that moment – died from a maelstrom of complications relating to cancer which are so obscure to me, even now, that I could not possibly tell you which of them finally ended his life.

In that film, Chihiro, the pre-teen hero of the piece, is taken from a world she knows and from the people who love her – dragged headfirst and put to work in a bustling bathhouse at the centre of a strange and (understandably) overwhelming spirit dimension. Her parents transformed into pigs and threatened with the kind of death that unfortunately tends to befall so many of the pigs of this world, she is forced – and there’s just no other way to say this – to really get her shit together. To put her childhood and her loss on hold, for just as long as it takes, and to just get through it. All of which feels like advice I could’ve definitely used.

By the time I’d learned to appreciate the finer points of the story – come to see it as an allegory for moving through a world in which the people that you love will, inevitably, one way or another, leave you to fend for yourself in a landscape that suddenly seems strange and frightening – I was already some way into the next decade of my life. A time during which, having already given up drinking once, I had very much given up the giving up and started back on it (and other things) again.

I was once more, or perhaps even still, looking for comfort and understanding from a source outside of myself: to paraphrase Donnie Darko, another film of my youth, I was a young man looking for something in all the wrong places. And so, while I didn’t come of age with Ghibli films, I did – eventually, some time later – become myself in their shadow and their glow. For that I will always be grateful.

*

For me, as a kid, Studio Ghibli had been hiding in plain sight. I had seen the DVDs of Princess Mononoke on shelves at HMV, the plush toys of popular characters like Totoro in shop windows, and even the companion manga books collected in their multiple parts on dedicated bookstore spinners. All the pieces were there, but something just hadn’t quite clicked for me yet. There was no feeling that this should become something important to me – fewer still that it would be.

For plenty of others, I know now that this was already the case. Not just in Japan, where the studio was and continues to be based – or even in the wider East Asian market, by virtue of proximity – but all over the world. What I had been seeing was just the evidence: the result of what, back then, would have already been twenty-five years of work at the very top of the animation game under the Ghibli name, and decades of groundwork before that even began. The combined product of centuries-worth of talent, pooled in perfect harmony.

*

Formed in 1985, Studio Ghibli was – and, at least in spirit, to this day very much still is – the project of its lead director, Hayao Miyazaki, the producer and former company president Toshio Suzuki, and a second acclaimed directing talent in the now sadly-departed Isao Takahata. Yet, as its enigmatic figurehead, and with the commercial success of films like Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle, Miyazaki’s name is the one which has become a byword for Ghibli itself. While it is certainly true that he is responsible for so many of its most acclaimed pictures, Studio Ghibli’s output would look very different without the input of its three founding fathers.

Without Takahata, there would be no Grave of the Fireflies,a unique and rending tale of familial love and death in wartime rural Japan (and one of those films guaranteed to truly ruin your day and probably the rest of your week), no Only Yesterday; a near first-of-its-kind as a realistic animated drama geared toward adults, and no Tale of Princess Kaguya – a masterwork of animation which, by all rights, ought to have reinvented the medium altogether, going not so much “back to basics” but back to the impressionistic roots of Japanese visual storytelling. And without Suzuki, whose creative vision brought them together under one roof, there would be no Ghibli filmography at all.

Miyazaki may well be the brightest and most visible star, but his light is far from the only one in the inky Studio Ghibli sky. Ghibli is not just the output of one man – it is more. Much more, even, than the work of those three men combined and the talents of those artists working under their direction.

There’s no need here to give you a potted history of Ghibli. Or, at least, I have no desire to do so beyond what you’ve now already read. After all, you’ve got access to Wikipedia and its innumerable sources. Instead, this is a book about meaning; about searching for something – fumbling for anything like an “answer” to a not-quite-certain question, in what can often seem like total darkness, and, hopefully, eventually, about finding it somewhere unexpected. In Studio Ghibli.

*

Combining animism, magical realism, and something more like a sense of “near-reality” in its films, Ghibli’s unparalleled animated repertoire is a uniquely crystalised vision of the world: a shared dialogue between creators and viewers – between art and reality. Its universe is not so far from our own: there are human beings with recognisably human traits, there’s food and drink rendered with famously saliva-inducing aplomb, weather of all the usual and less usual kinds, and all those things we take for granted as being everyday occurrences. But there is also a depth; a deeper magic to that minutiae – elemental spirits and animal gods – ancient beings, acting seen and unseen, as the engine behind it all. Asking us not so much to question what we know but to consider the possibility that there might just be more.

In short, it is a gift. A way of seeing, and an enchanted instrument for interpretation. But that does not make Ghibli films, Ghibli characters, or even those unmistakable Ghibli landscapes, a blank slate for the unconscious: these are not voids for projection, but something more like complex, individual realities to be inhabited and intricate narratives through which to move. They are experiences – created not just to be watched, but to be lived.

Like life in general, they are about both the inevitable end-point and the journey.

*

Chosen by Miyazaki, in what might well be called “uncharacteristically romantic” fashion, “Ghibli” is borrowed from the Italian word for a particular kind of hot desert breeze, named with the idea in mind that the studio would – as he put it – ‘blow a new wind through the anime industry.’ (Although there is also a much more typical video of Miyazaki, simultaneously crochety and good-humoured, laughing with an implied sense of scorn about the fact that “Ghibli” is just a word that he stole from the side of a plane.)

Beyond those auspicious and ambitious roots – or, despite his own dismissiveness of the meaning – Ghibli has proved to be a more appropriate moniker than even Miyazaki could have hoped. It is evocative of the unique feeling that the studio’s films stir in those who hold them close – and a constant reminder of why that embrace remains so warm.

In a sense, these films are voices of the past – carried on the air, whispered into our present-day ears: fantasy worlds that do not ask us to forget the one in which we live, but instead remind us to look beyond it. Not to ignore the subjects of sadness and grief and mourning, but to embrace them and – if possible – to find a sense of joy in that embrace, difficult as it may be. Most of us will live, but all of us will die. People. Things. Innocence. Youth. Eventually, even life as we know it.

Death – if nothing else – is certain. And, to that end, the Ghibli filmography is vivid and immersive proof that this outlook on life is not a cold or dispassionate one; not a mark of indifference to the act of being. On the contrary, its magic – both literal and artistic – is testament to the importance of what it is to remember the fact of mortality in all its forms and to own it, rather than allowing it to take ownership over us.

Miyazaki once said that ‘life is a winking light in the darkness.’ While all evidence suggests that the man himself would likely never suggest something quite so grandiose, Studio Ghibli is also that light for many. These are films which, in their empathy, their honesty, and their artistry, reveal more life and about death than that which they obscure with any sense of fantasy.