Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

For centuries, migrants from the heart of Germany have hoped for a better life in the United States of America, for human rights, peace and democracy. Countless took their chance and changed their new homecountry for the better. Like members of the Giessen Emigration Society in the 1830s. Like Edmund who dreamed of becoming a ship's captain. Or like Ruth, a Jewish child who had to flee from her village in 1938, and became an Accidental American.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 202

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedicated to

everyone here and In overseas

who loves the freedom of others

as much as his or her own.

Who cares and shares.

Who pursues happiness

and finds kindness, safety and truth,

humour, wonders and respect,

Justice, wisdom and tenderness,

true solidarity and peace.

Content

Dedication

Foreword:

Let’s go!

First Part:

Out of necessity to America. Hessian emigrants in the 19th and early 20th Century

Second Part:

Departure to freedom. Of 500 who set out to find and fight for human rights. Some of them have changed the country they settled in, for the better

Third Part:

Zweiback and Captain's Dinner. How a fiveyear-old and a seventeen-year-old from Hesse experienced their first sea voyage and what became of them and others

Fourth Part:

A home far away from home. Emigration becomes immigration. Hessian contributions to American history of the 17th and 18th centuries

Fifth Part:

In the light of Lady Liberty's Torch. How immigrants experienced their arrival on Ellis Island

Sixth Part:

Welcome Or Not Welcome? A fearful question. How the conditions of immigration to the United States have changed since the early 20th Century

Bibliography

Credits:

Writers, readers, singers and instrumentalists

Text and image rights

Epilogue:

Go on!

Let’s go!

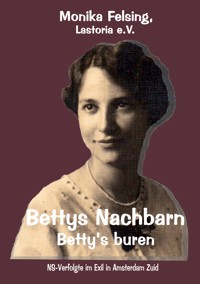

For uncounted Germans and other Europeans migration was the only way to keep or improve one’s life until the 19th and in the 20th century. They left their villages, their hometowns, their countries, the most uncomfortable comfort zones to start anew overseas. In one of its projects, our Historical Society Lastoria, Bremen, has done research, concerning for example early human rights and democracy movement in the 19th Century and refugees of the Nazi era. Historian and journalist Monika Felsing and other volunteers have told the stories of several Jewish and Christian families with roots in Upper Hesse or other parts of Germany and Europe, and got in contact with other researchers, genealogists, institutions and authors.

In 2022, the podcast project "Now we go... Overseas!” of Lastoria started with volunteers in Bremen, Berlin and Hesse. After a year, it became almost overnight a transatlantic project, supported by the genealogist Susan Eldridge nee Badenhausen in Connecticut, whose ancestor Edmund Badenhausen from Melsungen had become Capitain in the 19th Century and moved to the U.S. where he was in charge for the peer of Hapag and the Norddeutsche Lloyd in Hoboken, New Jersey. I have used Al for initial translations of my manuscript from German to English, and Susan Eldridge who had after a short, but understandable hesitation agreed to be the voluntary director of the English version, helped me to revise it, and the book has benefited from her extensive proofreading. A teamwork that I have appreciated and enjoyed very much! Together, we have turned the written words into an audio of several hours, and then, thanks to a good friend, graphic designer Wolfgang Rulfs, into this book.

In libraries and at kitchen tables, volunteers, mostly amateurs, have read the documents, the quotations from literature from the 19th Century, or sang songs, to keep memories alive. Professional musicians played music from various eras and in various styles. A Chanty Choir from Bremen sang a sailor’s song, Niki Rittenhouse from Connecticut the English version of the project’s theme: “Now we go... Overseas”. A brass band from Upper Hesse has contributed “Muss i denn”, and several audios from the well-kept archive of Lastoria have been used. Duo Eigenart from Nidderau for example played music from the time of the Social Revolution in Hesse, early 19th Century, on historical instruments at the Weidig weekend in Ober-Gleen in 2015. Klezmer historian and violinist Yale Strom from San Diego introduces the audience to Jewish Music, Burghard Bock from Bremen has interpreted “Di grine kuzine” on the mandolin. Veronika Bloemers from Frankfurt/Main plays a Sabbath song on a grand piano (an instrument by Steinway & Sons, a company founded by Heinrich Engelhardt Steinweg, born in 1797 in Wolfshagen in the Harz mountains, not far from Hesse, and emigrated in 1850 with his big family to the U.S.) in the Hohhaus Museum, Lauterbach. And we also proudly present an audio of Henry Smolen, grandson of the refugee Herbert Sondheim, playing Beethoven.

Readers and listeners will learn something about ordinary people’s dream of a new life and their contributions to American history, about members of the Giessen Emigration Society who hoped to settle in Missouri and to found, with the support of Americans of German descent, their own democratic German state in the U.S., a place where tolerance, human rights and liberty should rule. The podcast tells the story of some female pioneers in the U.S. and discusses women’s rights in the 19th Century. There were Jewish Hessians finding refuge in the U.S. and others who were rejected and sent to concentration camps. We accompany the German journalist Heinrich Lemcke during his visit on Ellis Island in the early 1890s, and ask how immigration laws have changed since.

Our Historical Society Lastoria wishes to thank every volunteer who has participated in this transatlantic project about migration, as well as everyone who has performed the research and published the information from which this was written. The podcast consists of six parts that are online, in the United States at badmorgen.wordpress.com. In Germany you can find them at monikafelsing.de. If you have any questions or want to support our volunteers’ work, please don’t hesitate to concact us in Germany at [email protected] or in the United States at [email protected].

But now... let’s go!

Out of necessity to America

Hessian emigrants in the 19th and early 20th Century

Now we go overseas 1

(Coversong of the old German folksong “Jetzt fahrn wir

übern See”)

Now we go overseas, overseas,

now we go over...

Now we go overseas, overseas,

now we go overseas!

On an old sailing vessel, vessel, vessel, vessel,

on an old sailing vessel,

departing hurts so...

On an old sailing vessel, vessel, vessel, vessel,

on an old sailing vessel,

departing hurts so much!

Up and away. The people of Hesse have left their hometowns. They go with their children: far, far away, via Bremen, Bremerhaven some also via Hamburg to America. We want to tell some of their stories and turn back time by a little more than two centuries, not guite to the eight years of the American War of Independence, 1775 to 1783. This is when the Landgraf of Hesse-Kassel rented thousands of his male subjects as soldiers to the British and they sang goodbye at the parade in Kassel:2

Yay to America!

To you, Germany, good night!

You Hessians, present your rifle,

the Landgraf is coming to the watch!

Goodbye, Landgraf Friedrich,

you pay us liquor and beer.

if we lose an arm or a leg, if men are shot

England will pay to you.

You lousy rebels, you,

beware of us Hessians!

Yay, to America!

To you, Germany, good night

Four decades later, the brothers Grimm have collected fairy tales told to them by women in Kassel. One is about four who are sentenced to death and run away, and begins like this: "There was a man with a donkey who had served him faithfully for many years, but whose strength was now running out, so that he became more and more unfit for work. The master not only wanted to cut back on the donkey’s food, but he also did not want to feed him anymore. The donkey, noticing that there was no good wind, ran away and made his way to Bremen; there, he thought, you can become a town musician.”3

The donkey, the dog, the cat, and the rooster are still mentioned as emigrants in the 1819 edition of the "Children's and Household Tales”, even if they did not get far. Not even as far as Bremen, to be exact. Millions of people, however, are driven beyond the borders of today's Germany, to countries about which they know little. Some move overland to the east, to Poland, Lithuania, Russia or Hungary. Others venture across the Atlantic. In 1819, anyone who wanted to leave and could read, and there were very few of them at the time, learned something about the "Ordinance on the Emigration of Subjects to America, in particular the Conduct of the Police Directorate of the Free City of Bremen in the event of unsuccessful emigration projects”. Whether deciphered, passed on or read aloud, everything is eagerly devoured.

In March 1835, the Bremen shipowner Friedrich Jacob Wichelhausen placed the following advertisement in the newspaper: "Announcement. All the ships I handled last year with passengers to the United States of America have not only arrived there happily and after a voyage of 35 to a maximum of 45 days, but the passengers have also shown their complete satisfaction with the passage, with the treatment of the ship's captain and the food received on board by a written testimony, which then also prompted me to pay the ship's captains the bonus promised to them in this case. Mr. Werner Ramspeck Junior had the kindness to take over the agency for me in the local area for the acceptance of passengers. And I therefore ask all those who intend to leave for the United States of America this year to turn to this gentleman as soon as possible. The same person is authorized to receive the earnest money for my account and to agree with the passengers on the conditions of the crossing.”4

Now we go overseas

In the port of Bremerhaven

we went on our...

In the port of Bremerhaven,

we went on our ship!

With all our belongings, longings, longings, longings,

With all our belongings,

we started our...!

With all our belongings, longings, longings, longings,

with all our belongings,

we started our trip!

Some villages even pay for the crossing for their poor and others whom they want to get rid of. In his article on "Emigrants from the parish of Maulbach" in a publication of the Alsfeld Historical Society, Wolfgang Seim gives several examples of this. His most important source was the emigrant lists of Karl Geisel in the city archives of Alsfeld. Among those who left the country at the expense of their home community was the 28-year-old Balthasar, a beggar whom the community of Dannenrod probably sent to his older sister in the United States in 1854. In a profile from 1851 he is described as "mentally weak". A few decades later, the authorities of the United States no longer allow mentally retarded people to enter the country.5

The day laborer Johannes Weber6, in his mid-50s from Dannenrod, is also to be deported to the New World in 1871. This does not succeed: He should have gone to New York with the “Christel”, but he returns home in 1872 and claims that the German Society of the City of New York, which takes care of newcomers, has sent him back. Nobody believes him. Did he even go on board in Bremerhaven?

Most of them have to pay for their passage themselves or go into debt bondage with Americans. Shipowners, agents, carters, outfitters, innkeepers, and hoteliers, all earn money from emigration. In the Vogelsberg and neighboring regions there are several contact points. Since 1828, the Storndorf freight driver Heinrich Rausch has been authorized to broker passages, as can be seen from his advertisement in a newspaper of February 1848: “Emigrants to North America can continually be transported on good solid three-masted first-class ships at the cheapest prices. In bringing this to the attention of the emigrants, I notice that for almost 20 years now I have been engaged in the transport of emigrants to North America to the greatest satisfaction of the emigrants and am therefore licensed as a certified agent and have provided an appropriate deposit. I take care of the transport from here to Bremen with my own wagon and horses, scheduled for the first and fifteenth of each month.”7

And when we go on board, go on board,

and when we go on...

And when we go on board, go on board,

and when we go on board,

Ours will be the tweendeck, lower, lower tweendeck,

Ours will be the tweendeck, and well be lice's...

Ours will be the tweendeck, lower, lower tweendeck,

Ours will be the tweendeck,

and we'll be lice's port!

Expectations are high, and so is uncertainty. As early as 1830 they are singing in Germany:8

Oh, how many beautiful things

you hear from America.

That’s where we want to go to,

that’s where you have the most beautiful life.

Sometimes it so cold here, we could freeze to death,

and can hardly move our fingers.

And it is warm there even in winter.

Nobody gets poor buying wood.

The largest fish known,

you can catch it with your bare hand.

The carp are, on my honor,

often weighing half a hundred kilo.

The chocolate and sugar cane

grow at every pond.

Gabriele Gonder Carey with her husband and her sons.

It is hard to believe:

Wool grows on every tree.

And when we came to the port,

we were pale with grief!

Everything we took with us,

we had to pay for the freight.

We went out to sea,

and many cried out, "Oh and woe!”

And the children look pathetic.

Oh, Father, oh, Mother, when are we home?

Over the decades, the journey becomes shorter and the crossing a little more comfortable. In March 1841, Bremen shipowners advertised in the Alsfelder newspaper: "Notification for emigrants to North America. The undersigned hereby inform the public that on the first and fifteenth days of each month, as hitherto, they will dispatch large and fast-sailing, copper-plated, three-masted German ships from Bremen equipped with high spacious false ceilings to Baltimore and New York and at the appointment of the Administrator of the Grand Ducal Hessian Postal Administrator, Mr. Philipp Bäppler in Schellnhausen, as their agent."9

In the spring of 1851, around 3000 people left via Bremen in one month. Over the course of time, more than four million people from Europe are expected to take this route, for different motives. Thus, Democratic lawmakers flee overseas as the gains of the March Revolution of 1848 are abolished. They will be called “48ers” in the United States. During the economic crisis from the Weimar Republic, unemployed people such Heinrich Geissler from Ober-Gleen, the 23-year-old ladies’ and men’s tailor will leave. He emigrated in 1922 and found work in Baltimore. His nephew Walter Ruppenthal, the son of the village midwife Marie Ruppenthal, née Geissler, told in an e-mail in 2014 how emigration came about and what happened afterwards: “The Geissler family already had relatives in Buffalo with whom they were in correspondence. This was mainly run by my mother. At that time, she also announced to the Americans that her brother was unemployed and let them know that he would now actually have time to put their clothes in order. More or less an empty phrase, the consequences of which could not be foreseen. The next letter from Buffalo was accompanied by passage booking to the United States. My mother was severely reprimanded by her parents for this. The family was turned upside down. But my uncle Henry thought that was quite good and took the opportunity. With the help of relatives, he rented a small apartment and from then on carried out sewing work of all kinds. Business was going well, and he soon was able to gratefully return the money for the crossing.”10

He took his chance. Therefore, no one will call him an economic refugee. Some Germans, however, follow the waves of emigration with mixed feelings. The song “A Proud Ship” is published in 1925, when steamships have long been traveling between the continents.

A proud ship 11

A proud ship slowly slides through the waves

and carry on our German brethren.

The Eastern wind is blowing, the white sails are swelling.

America is their destination.

To stand on deck like this,

to look homeward:

America, to distant colonies.

Do you see them moving across the great ocean?

That's where they're going! Who dares to ask:

Why do they leave their home country?

Poor Germany, can you bear it,

how your sons are so harshly banished?

Look here, you who want to make people happy!

Look here, you oppressors!

See your best workers fleeing!

Do you see them moving across the great ocean?

There they move on blue ocean waves.

Why do they look back wistfully?

Are they so badly treated at home,

that they are now seeking their fortune in a foreign

Land?

What they couldn't find here,

they try to find there.

They sall away from German soil

and then find their grave in a foreign country.

Walter Ruppenthal’s uncle became an American but stayed in touch with his family in Hesse. “In 1926 he came to visit me to attend my baptism and to persuade his bride, who had stayed behind in Ober-Gleen, to come along”, the nephew wrote. “As far as I know, she would probably have been willing to do so. Unfortunately, the parents’ veto caused this project to fail. Some people said that only ’good-for-nothings’ go to America. As a result, the engagement broke up. My uncle Henry then met his future wife Käthe, born in 1905, from Ernstroda at the German Club. Together they ran a ladies’ tailor's shop, which probably went very well. In 1934 they bought a slightly larger house. Their son Herbert was born in 1930 and their daughter Betty in 1935. Both the parents and children have visited us several times in Germany. And, of course, we've been there several times.”

Where there are Germans, Germans go. This also applies to emigrants from Upper Hesse: in 1927, the Jewish tailor Nathan Lamm12 from Ober-Gleen goes to Buffalo, as well. He explains to the immigration authorities that he wants to go to Buffalo, where Heinrich Geissler lives. In the 1930 Census, he is listed as Max Nathan Lamm, as Amy B. Cohen, the author of the Brotmanblog, has found out. Nathan worked in the United States, first as a baker, then in construction; was in the United States Army from 1942 and returned to Buffalo after the end of the war. In those years, opponents of the Nazis and those persecuted because of their Jewish origins desperately tried to get a visa for the United States. What happened to some of them we will learn later. Let's go back to the early 19th century, first.

It is not uncommon for many people to get rid of their money before they are leaving their homecountry. And so, in 1832, the Bremen Senate, concerned about the good reputation of the city, instructed the innkeepers “that everything that seems necessary for the benefit of those who have chosen Bremen as their place of emigration should be taken into account as much as possible”. In order to protect people leaving Europe via Bremen, the first state law is passed in Germany in the same year: the "Ordinance on Emigrants with Local or Foreign Ships”. From now on, passenger lists are mandatory and, from 1852, must be handed over to the "Verification Bureau for Emigrants”, which was specially set up by the Chamber of Commerce.

If subjects want to leave Hesse-Darmstadt, they must first submit an application. The mayor forwards it to the Grand Ducal District Office in Alsfeld. The newspaper then calls on potential creditors to come forward within three months. More and more people are arriving in Bremen. The first way leads to the verification office. And they are looking for accommodations. Are there still rooms available in the hostel "The City of Baltimore” at the Neue Markt? In the “City of New York” on Grosse Johannisstrasse or “Zum Admiral Nelson” on Langenstrasse? There are not enough rooms anymore. And so, businessman Friedrich Missler has emigration halls built in Bremen-Findorff. He offers an all-round service: lodging, tickets, insurance, information. Mostly via ships of the Norddeutsche Lloyd.

Those who are not allowed to leave, vanish: Young men who want to avoid military service are among them, such as Friedrich Trump from Kallstadt an der Weinstrasse, who will become rich as an innkeeper and brothel owner during the gold rush. Poachers also disappear without deregistering, debtors, sometimes even entire families, Social Revolutionaries who are wanted by the police, husbands who abandon their wives, young people and others who do not expect to get a permit. On 1 January 1848, a newspaper in Upper Hesse reports: “The Regional Court of the Grand Ducal Hessian of Homberg to the mayors of the district. In recent times, it has often been the case that persons have emigrated to America without first entrusting anyone in their former homeland with the care of their affairs, which then sometimes resulted in the ordering of costly judicial curates, but always the delay of inheritance disputes and similar transactions. We therefore call on you to draw the attention of the emigrants, in their own interest and the interest of their remaining relatives, to the disadvantages of failing to make such a power of attorney. Signed, G. Klingelhöffer.”13

In Hesse-Kassel, emigration is no longer illegal from 1831 onwards. People have already left before, as it says on the pages of the Neustadt family research.14 From 1820 to 1840 they gathered at the “burned oak” in the Wasenberg Forest to trek north. They need four to five days with their horse-drawn carriages for the first stage. In Hannoversch-Münden, horses and carts are sold. And the journey continues with Weser barges to Bremen and Bremerhaven, five to six days on the river. In 1852, the Main-Weser Railway is built, connecting Kassel and Frankfurt am Main. For many emigrants from the region, this shortens the journey by days. You take the train to Karlshafen and board a Weser steamship, then a sailing ship in Bremerhaven. In advertisements, passengers leave reviews after the crossing, whether paid or on their own initiative. In 1841, in the newspaper from Alsfeld the people read: “Thanks to Captain J. H. Bosse. The undersigned passengers of Mr. Friedrich Jacob Wichelhausen in Bremen feel compelled of their own accord to praise the excellent efficiency, untiring attention, activity and caution of the Captain, Mr. J. H. Bosse, of which they had the opportunity to convince themselves day and night, to boast publicly and both for this and for the courtesy shown to them, kindness, and humanity to express their warmest gratitude. With the frequent complaints about the carelessness of some captains, the happiness of getting into such philanthropic and sympathetic hands is doubly beneficial, and we can only hope that a similar thing will happen to our subsequent compatriots. New York, June 4, 1841, E. A. Schumann for himself and on behalf of the remaining 185 passengers.”15

Why break up when you can stay together? In Neustadt in Kurhesse, some families decided to emigrate together in 1832, as can be read on the website about family research in Neustadt. The “Columbus”, a three-masted ship of a Bremen shipping company is to bring the almost 200 people from Neustadt, Momberg and the region to America. At the end of May, the ship departs from Bremerhaven and reaches New York in mid-July, after a trip of six weeks. Around 1880, the emigrant song was sung in Upper Hesse:16

Now is the time and hour

to travel to America

The wagons are already at the door.

With wife and children we march.

The friends and our relatives

reach out to us for the last time:

"Friends, don't cry so much,

see you now and never!"

And when we arrived in Bremen

and looked at the big water.

We are not afraid of a waterfall:

God is everywhere.

And when we came to Baltimore,

we raised our hands

and exclaimed: Victoria!

Now we are in America.

We traveled even further away

and trusted in dear Lord,

The idleness is now over.

Brothers, we have to work!