15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The virtue of obedience is seen as outdated today, if not downright toxic - and yet, are we any freer than our forebears? In this provocative work, Jacob Phillips argues not. Many feel unable to speak freely, their opinions policed by the implicit or explicit threat of coercion. Impending ecological disaster is the ultimate threat to our freedoms and wellbeing, and living in a disenchanted cosmos leaves people enslaved to nihilistic whim. Phillips shows that the antiquated notion of obedience to the moral law contains forgotten dimensions, which can be a source of freedom from these contemporary fetters. These dimensions of obedience - such as loyalty, discipline and order - protect people from falling prey to the subtle forms of coercion, control and domination of twenty-first-century life. Fusing literary insight with philosophical discussion and cultural critique, Phillips demonstrates that in obedience lies the path to true freedom.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 315

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

1 Allegiance

Notes

2 Loyalty

Notes

3 Deference

Notes

4 Honour

Notes

5 Obligation

Notes

6 Respect

Notes

7 Responsibility

Notes

8 Discipline

Notes

9 Duty

Notes

10 Authority

Notes

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Begin Reading

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

171

172

173

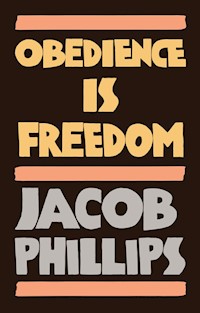

Obedience is Freedom

Jacob Phillips

polity

Copyright © Jacob Phillips 2022

The right of Jacob Phillips to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2022 by Polity Press

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press101 Station LandingSuite 300Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4935-1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021949835

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Introduction

Readers picking up a book entitled Obedience is Freedom, with chapters entitled ‘Allegiance’, ‘Loyalty’ or ‘Obligation’ and so on, may be expecting an academic treatise. Perhaps they will expect this introduction to start by listing some examples of how obedience is today considered irredeemably toxic. Then, a discussion of freedom, suggesting today’s preference for interpreting this as individual self-fulfilment often leaves people frustrated, isolated and at times even enslaved. The ground would then be prepared to state the thesis of this book: a rediscovery of obedience (and subcategories like allegiance, loyalty and obligation) promises a more enduring and genuine freedom than that offered by today’s self-fulfilment paradigm. Indeed, many great thinkers have long since argued that an avoidance of restraint serves only to intensify the degree to which we are restrained, and that genuine and enduring freedom is to be found through obediently entering into the ways personal choice is ever limited by the networks of responsibility in which we live.

Having outlined the basic position in the Introduction, such readers might expect the chapters to outline, in prosaic terms, exactly how the themes under discussion contribute to that more authentic freedom lacking in today’s world. These would then begin with comments on the etymology of the chapter heading. These terms often combine elements of restraint or obedience with expressions of spontaneity or freedom. The word obligation, for example, derives from the past-participle stem of the verb obligare, meaning ‘to bind’, and yet also from the noun obligatio, which is connected with expressing gratitude; hence the old English phrase ‘much obliged’. From findings such as these, some discussion of ancient texts would be expected, particularly those of Greek and Roman philosophy. Then a critical discussion with more contemporary voices could follow, working towards the overarching conclusion that obedience is not only connected with freedom in ways we seem to have forgotten, but that these two are so mutually dependent they are indistinct: hence, obedience is freedom.

A reader expecting a book of this nature, however, will not find it in this volume. This is not a systematic or polemical text that seeks only to argue in explicit and straightforward terms. Rather, the book includes concrete histories describing specific events from the last three or four decades. It also engages not only with writers on obedience and freedom, but with literary interlocuters like Charles Dickens and Karl Ove Knausgaard, neither of whom would usually be expected to be found in a book of this nature. While there is philosophical discussion, there are biographical reminiscences too and much material that is taken from my own life, particularly in drawing on cultural phenomena that others of a similar age and background might recognize.

Discerning readers who want to understand the sources for the notion of freedom that underpins this book are recommended to read some St Augustine and Dietrich Bonhoeffer (which is not to say I pretend either thinker would endorse this book). Those wanting to understand more recent discussions would be advised to read Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed and maybe The Cunning of Freedom by Ryszard Legutko. Readers of this book need to know why Obedience is Freedom has been written in an offbeat way.

This stems firstly from the intellectual fecundity of more offbeat realms of discourse in the UK and USA, particularly, since around 2016. As a young academic, I took great interest in witnessing freer, more engaging and often more genuinely insightful work emerge in obscure online publications than in peer-reviewed journals and the volumes of academic publishing houses. Rather than argue the now well-worn trope of ‘this thing you think is left-wing is actually conservative’ and vice versa, it seemed more effective to enter into such things with elements of narrative. Concrete stories and their atmospheres disclose things that contemporary presuppositions struggle to relate. A great many conceptual binaries beside obedience/freedom have been broken in recent years, but these binaries can be glimpsed in a restored state by observing how they interrelate in recent history.

If there is a method on display here, it is synaesthetic – an attempt to bring together things we cannot imagine being the same, like seeing smells or hearing the sensation of touch. These types of interrelations are often only lightly buried in the recent history of Western cultures, just under the surface, where obedience and freedom can still be seen as two sides to the same coin, each requiring the other.

Secondly, while it has become increasingly apparent that much interesting writing is happening ‘outside’ the authorized platforms and credential system, the content of this writing is often similarly ‘outside’ dominant ideological paradigms. These paradigms are most commonly associated with identity politics, although its roots go back much further, as I argue later on. A discourse that takes place ‘outside’ the dominant worldview reminded me of a time when alternative manners of living were being explored by those then ‘outside’ mainstream society, particularly in the 1990s. For me, the two forms of ‘outsideness’ can inform each other, just as the themes and concepts of this book were once subtly linked together. There is much to be learned, albeit often negatively, about how things like ‘allegiance’, ‘obligation’ or ‘respect’ were bound up with the alternative worldviews of peaceniks, squatters, travellers or road protestors. That is, with people thought to be archetypal seekers of freedom.

Thirdly, I would say that the ‘conservatism’ on display in the pages of this book is of a broadly postmodern character. This does not mean surrendering to moral or cultural relativism, by any means, but involves a focus on how writers are implicated in their subject matter and vice versa. It means writing from the point of contact between self and world, because the juncture of subjectivity and objectivity discloses things that an exclusively subjective or objective approach does not. This sort of postmodernism is, paradoxically, exactly what those associated with ‘postmodern ideology’ today have entirely neglected, while claiming to celebrate it in abundance. Identity characteristics are frequently foregrounded in every discussion, but not fostering freedom of exploration and expression so much as closing everything down to a mere monologue. Those who would most explicitly celebrate the interrelation of subject and object are today those most likely to break the binary between the two, so only one remains, under the rubric of ‘lived experience’ (see Chapter 5). In any case, I lived through much of what is written in this book. It amused me no end when the editors of an online journal tagged an essay I’d written in this style as ‘fiction’. No word of this book is fiction.

The reasons just listed give some indication as to why I chose not to write this book using standard means of argumentation like those described at the outset. But before leading people into the countryside of West Berkshire in the early 1980s, the record shops of mid 1990s Hackney, or the exodus to Cornwall to watch the solar eclipse in 1999 – it is only fair that I at least offer some preliminary orientation to show how the chapters work towards the claim that obedience is freedom.

Chapter 1, ‘Allegiance’, highlights the obedience involved in child-bearing and child-rearing, entailed by the visceral attachment of mother and child. Changing attitudes to natality based on wanting a greater freedom, I contend, are symptomatic of one of the great challenges of our age, in which mutual allegiance one for another in a shared culture is perpetually at risk of fracturing and fragmentation, of warring cultures within one society. A culture that celebrates the commonality of mother and child is one set free to celebrate its own commonality on a societal scale. A culture that is hostile to the most visceral commonality is one that threatens to lose all sense of common ground whatsoever.

Chapter 2, ‘Loyalty’, focuses on a surreptitious slip in the understanding of the obedience associated with this term, whereby it is made secondary to personal choice: being loyal to those with whom you agree or towards whom it is advantageous to evince loyalty. The chapter enters into critical discussion with Jonathan Haidt, David Goodhart, Christopher Lasch and Peter Sloterdijk, who have each tried in different ways to interrelate the legitimacy of loyalty to one’s society or culture within an age of rapidly changing values and views among citizens. The chapter concludes that loyalty is the fruit of freedom, not its opposite; that cherishing the ways people share belonging enables them to let that belonging take precedence over optionality and preference without entailing anything abusive or toxic.

Chapter 3, ‘Deference’, is based on the position that many of the ills of today’s world are rooted in the dissociation of people from the networks of responsibility by which we live. Self-fulfilment, as social mobility, is presented as fostering a literal self-centredness, whereby one’s position in society is made the measure of personal worth, one’s centre. By contrast, and exemplified in the novels of Charles Dickens, I argue that moral and economic worth or dignity must never be confused, that one’s moral value, or centre, is bound up with the good of the whole to which one contributes. I also argue that separating moral and economic value can liberate people from the various narratives of affliction that pervade our culture, because those narratives serve to cover up the various issues with self-esteem and mental illness that attend aggressive meritocracy. The ability to defer is indicative of a society where moral and economic worth are disambiguated – for deferring to others is acutely painful if their perspective is deemed representative of some sort of greater dignity than one’s own. Deference just means accepting another’s viewpoint as better placed than one’s own.

Chapter 4 is entitled ‘Honour’ and turns to love, sex and desire in the internet age. The point here is that obediently accepting another’s standing as an ‘end in itself’ and never a means to one’s own ends, in a loving relationship, means honouring that person as someone who is not ensnared in one’s own schemes or objectified. To honour someone is to hold dear to the boundary between yourself and another. Yet this boundary liberates people to love each other genuinely, not chase after others as vehicles for self-satisfaction.

The next three chapters shift gear to more societal concerns, beginning in Chapter 5, ‘Obligation’, with a critique of what might be grandly termed the epistemology of identity politics. Drawing particularly on the hermeneutical philosophy of Wilhelm Dilthey, I argue that the distinctive intellectual activities of the humanities (most fundamentally, interpretation) are structurally different to the natural sciences because of an inherent twofold structure of obligation. That is, to interpret something requires taking heed of a mutual obligation to subjectivity and objectivity. Natural science as classically understood adheres only to the obligation of objectivity. Yet, much of today’s discourse on the humanities breaks the binary in the other direction, claiming all is subjectivity. Moreover, older approaches to the humanities argued that these disciplines just reflected the way people actually live. In life, we perpetually seek objective truth in a way that is properly integrated with subjectivity. Basic human cognition serves both masters.

Chapter 6, ‘Respect’, I wrote with great hesitation, as it entailed going into some of the most vexatious territory of contemporary society: race. The thesis here is that most discourse around race-relations, particularly since 2020, has drawn on American racial discourse, despite the fact that that discourse is often ill-fitted to a UK context. The effect of unconscious bias training sessions, for example, is to try to leverage respect between different ethnicities artificially and often in a way disconnected from the lived realities in which particular ethnicities have forged a particular shared culture in Britain for decades. This is not a pluralist multiculturalism I have in mind, but something much harder to achieve – mutual participation in a culture that is shared. I contrast the mutual, organic respect that is won by sharing a culture with the forced, artificial respect associated with terms like ‘allyship’, which are themselves often used by people who haven’t lived within a shared culture themselves.

Chapter 7, ‘Responsibility’, discusses ecological concerns as expressed in the 1990s compared to the present day. Between the two periods, another broken binary has emerged – between cultural and social conservation and environmental conservation. This break is intensifying rapidly, with the current vogue for language of crisis and emergency pushing towards a near-permanent state-of-exception, radically disconnected from the past. But we need not go too far back in history to see how nature and culture were much more closely related than they are today.

The book then shifts gear again for the final three chapters, turning to even broader questions about language, the cosmos and, finally, authority. Chapter 8, ‘Discipline’, finds the epitome of the interrelation of obedience and freedom in poetics. Poetry is held to be writing freed from even the normal strictures of language and yet the requirements of the form are traditionally much stricter than prose. The fact that language today so easily slips into a bureaucratic and managerial turn of phrase (or anti-poetics) is symptomatic of our inability to use discipline in service of freedom.

Chapter 9, ‘Duty’, continues in a literary vein, bringing the six-volume autofiction work My Struggle by Karl Ove Knausgaard into dialogue with the differing cosmologies of the premodern, modern and postmodern periods. This chapter presents the view that premodern cosmology had a sense of duty ‘hardwired’ into it, not least due to its inherently God-centred structure, which was not entirely forsaken in the modern era. Knausgaard’s work gives voice to premodern and modern impulses, stubbornly resisting the collapse into cosmic nihilism associated with postmodernity – particularly when he is in everyday situations of duty, such as caring for the young.

The book closes in Chapter 10 with a theme that surely sums up all those covered thus far: ‘Authority’. This broken binary is perhaps the most important in showing how obedience perpetuates freedom, the degree to which it is indistinguishable from it, and vice versa. What many consider obedience today is just blind subjection, which is why there is some truth behind contemporary unease about the term. Similarly, what many people consider authority today is just an exertion of power, which supervenes over assent, again helping to explain why it has become a debased term. This chapter seeks to show that genuine obedience always involves a measure of assent and the genuine expression of authority has no need for the exertion of the power. However difficult it is for us to envisage this now, the interrelation of obedience and authority once stemmed from self-evidence, from the unquestioned conviction that those in authority were mandated to their position. Today’s various ‘contractual’ forms of obedience effectively undermine authority and tend to get ensnared in individual desires, as indeed authority founded on just brute force undermines obedience and tends to unleash chaos.

The final scene of the book describes the notorious eviction of an illegal party on the Isle of Dogs in 1992. In the heat of the moment, the battle scene was indistinguishable from a dance, just as in today’s world the culture wars are a form of recreation and entertainment, particularly on social media. Each set of opponents in that battle considered themselves sworn enemies. I argue that they were actually on the same side, unwittingly, just as those who want to resist all authority often end up in a grimly restrained manner of living and those who celebrate subjection slip into anarchic and antinomian lifestyles. In the small hours of the night, for a few short moments, the effects of this broken binary came together on the dancefloor in a field in a mysterious enclave of east London. From that moment we can glimpse what healing such binaries will entail. That is, that obedience is freedom.

1Allegiance

An area of common land in West Berkshire lies near an intersection between the industrial cities of the Midlands to the north and the ports on the English Channel to the south. The same spot is intersected lengthways too, connecting west and east on the old horse-drawn carriage route between London and Bath. The common land is a few square miles of woodland, heath and scrub. For centuries it would hardly merit much attention. Being common land it has no explicit purpose as such; it is simply ‘there’. But this land is also itself the site of an intersection of a different type. This land has a distinct history as a place on the intersection of war and peace.

This is documented from the time of the English Civil War. In 1643, Parliamentarian troops paused there to ready themselves for what was to be a decisive battle of that conflict. There are traces of much older earthworks still perceptible beneath the soil too. Long, linear banks of earth dated to the fifth century may have served a purpose for Roman troops, as even the circular Bronze Age pits nearby could have been used by a tribe practising with their weaponry before setting off to defend their settlements. It is said this site was later an outpost for soldiers preparing to defend Anglo-Saxon Silchester from attack. A map from 1740 shows a military camp set up there and in 1746 this camp was the base for despatching troops for battle with Bonny Prince Charlie. By 1859 it was being used as a training camp to prepare for a French invasion. There were 16,000 troops stationed there in 1862; in 1872, it was 20,000. Later it was used for infantry training for those going to the Western Front and eventually it was taken over by the Ministry of Defence for use as an airbase for the Second World War in 1941.

The history of this common land is given over fully neither to peace nor war; it is where they meet. This is where peacetime prepares for war. The order and obedience required for battle are established here. Yet this is also where fighters return to recuperate in peace, free from the demands of the fray. This is then a place of rest and regeneration.

A decisive change came some decades after the Second World War. This could be when the history of this place reaches a crescendo, when the meeting point between war and peace is suddenly brought into focus. People will then see this as a place that discloses that which is held in common by war and peace. For even winners and losers belong together. Both sides play the game. Both enter the scene, take the risk, yearn for the prize. To attempt to win the battle is to consent to possibly losing the battle. To enter into war is to accept you might not have peace on your terms. There is common ground between sides, in that each side shares something fundamental with the other. This is something beneath the battle itself, functioning like the rules of a game, tacitly present – just ‘there’ – like common land itself.

War and peace require a specific place of meeting if they are to be differentiated from one another. If times of war cannot become times of peace, the battle will never cease. Then, even in peacetime, everyone is at war. Recreation is riven with contention, people mistake combat for contentment. Order and obedience no longer intersect with rest and regeneration, because there is no boundary where you pass from one into the other. With no common ground from whence to be despatched into the heat of battle, there is no common ground to which to return and rest in the cool shade. War becomes cold war. Peacetime becomes intensely heated. Those who would feel the rush of victory can only do so if others are to feel the sorrow of defeat. There must be commonality from which each side departs, but also to which each side can return. In this belonging, obedience meets freedom.

The decisive change in the destiny of the common land came with the Cold War. NATO announced they would deploy cruise missiles in Europe on 12 December 1979. In 1981, it was reported that these missiles would be housed on two sites in England, one of which was this common land. It would provide a base from which military trucks could depart carrying these missiles if or when they were launched at important cities in the Soviet Bloc. The missiles were to be kept in large concrete silos, six in number. These resemble ancient ziggurats or pyramids, with heavy shutters opening to vast chambers, where their precious cargo would be immersed in the deep darkness within. It is difficult for us fully to appreciate how sinister these seemingly sentient missiles seemed in an age less technological than our own. They were remotely controlled and could fly a thousand miles below the flight radars. Each one contained enough atomic power to detonate an explosion sixteen times the size of Hiroshima. The spark of Prometheus lay nascent within each silo, ready for the floods to break forth upon the Earth when the shutters opened.

In a pamphlet from the early 1980s, a mother in a nearby town describes the moment this new purpose for this local land was announced on the news:

I had seen a BBC TV programme about nuclear war … It came to the bit about putting dead bodies in plastic bags with labels on and leaving them in the road to be collected. I sat in front of the television, my one-year-old in my arms, my heart sinking with fear. Someone, somewhere, is actually accepting the fact that my children will die. Someone, somewhere, is quietly planning for the deaths of millions. This is not a dream, it is real.1

This mother became one of many thousands of women who protested against the cruise missiles base in the years that followed. She had joined with others in organizing a march from a nuclear weapon’s facility in Cardiff to the common land and the scenes that followed are those with which this common land is now always associated: Greenham Common.

Initially they called themselves ‘Women for Life on Earth’. Leaving Cardiff on 27 August, they arrived on 5 September: ‘a long straggling line of women and children tramping through the dusty Berkshire lanes with leaves in their hair’.2 The single-carriage roads that led up to the site were arched over by the boughs of ancient trees, under which far more orderly battalions had once marched in lockstep. The woodland on either side was birthing its September fruits. The leaves were still green and lush, just tinged by the encroaching autumn.

When nature called, the kids would run ahead and duck under these trees, clambering through the leaves into dusty enclosures enclosed by broad, low branches. Some would dare to run further into the woods, wanting to be first to glimpse the eight-foot wire fence recently erected around the Common. On the other side of this fence, the grass had that scorched yellowy colour that can make the English countryside in late August feel almost Mediterranean, if only for a few long days. Squinting in the summer sun after emerging from the trees, the kids saw freshly tarmacked roads and a few clusters of USAF buildings in the distance. The marchers emerged from the mysterious hollows and reaches of the English countryside to approach the main gate. Mowed grass verges appeared, with gorse between them and the woods, and neatly trimmed little privet hedges in front. Coming from the musty darkness of the trees into the brightly dazzling sun, the newly landscaped terrain seemed fuzzy and unreal.

There was a carnival atmosphere. The women had a folk band playing alongside them and ‘they all looked so beautiful with their scarves and ribbons and flowers … The colours, the beauty, the sun … and so many people’.3 Some had decided to chain themselves to the fences and maybe it was the joyful intensity of the occasion that led some of the others to decide they could not simply go back home and return to normal. Some set up a large campfire and slept out under the stars. Over the following days provisions arrived, makeshift structures were erected and, around the nucleus of the fire, some of the women decided to stay indefinitely. The encampment was later named Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. Over the next three years it developed into what is now a well-known chapter in recent English history.

Within a few weeks it was decided it should be a women-only space. Some of the men present had been confrontational with the authorities, taken control of elements of the camp, or been overprotective of the women during skirmishes with bailiffs and police. These behaviours were not welcome. Numerous direct actions, court cases, imprisonments and campaigns took place in the next three years. The most well-known event is probably the ‘Embrace the Base’ event on 11 December 1983, when 30,000 women encircled and enclosed the entire base, linking arms around the nine-mile perimeter fence. There were marquees set up by the main gate for refreshments and childcare. The kids inside were kept amused with painting and makeshift puppet shows and their creations were later used to decorate the barbed wire. The event was on national television news. During the report, talking heads were interviewed in front of the main gate, voicing either approval or disapproval of the action. The kids’ brightly coloured paintings and puppets could be seen some way behind them but the wire fence was not visible at such a distance. Their creations thus seemed to be suspended in mid-air, hovering on the horizon. The women’s children, seeing their pictures on the TV, would be overcome with excitement and pride. Their triumphant cheers drowned out the droning commentary on the merits or demerits of the event itself.

Other direct actions were more volatile, taking place under cover of darkness. The project to house cruise missiles at USAF Greenham Common involved regular manoeuvres, when military trucks would take the missiles out of the silos and drive them around the surrounding countryside of Hampshire and Wiltshire, usually to a firing range on Salisbury Plain, five miles west of Stonehenge. To prepare and practise for a launch, the missiles would be edged out of the Greenham silos with great care, with much monitoring, pacing and controlled moments of focused pushing. Then the warheads left their dark place and were exposed for a moment to the night air and the stars, before being bundled hastily into the cribs built onto the military trucks waiting outside. These nuclei of awesome atomic power were then borne along the country lanes, passing through the high streets of small local towns, around the market squares and past the pubs, newsagents and grocery shops.

The women had phone networks on 24-hour alert all around the surrounding counties and would mount spontaneous blockades and sit-ins on the country lanes to stop these manoeuvres. These blockades developed into liturgies with regular features; sometimes the lighting of flares or the smearing of mud on the trucks’ windscreens while the convoy waited for police to clear the roads. Often, the operation would be aborted and the missiles sent back in retreat. Returning to the Common, the ancient role of Greenham would then recommence. This was always a site of both exit and return; a place from which people could depart into battle, but also come back to peace. The missiles went from ex utero to in utero. The shutters would be reopened, the cargo carefully laid back in the immersive darkness. As the soldiers trekked back to their lodgings shortly before dawn, they would hear the triumphant women drinking and singing in victory around the dots of flame they could make out coming from their fires all along the perimeter fence. With each battle’s end, there was a common place to which people returned.

The Women’s Peace Camp was a nexus of intersecting battlelines. There was the intersection of west and east. This was the making local in parochial England of the architectonic power blocks of the Cold War. This was where the opposition of the ‘free world’ to ‘communism’ was not rhetorical, it was real. It was also where the faultlines in domestic politics met, still then largely categorizable as Left and Right. The actual battles of the Cold War were never really between Americans and Russians, nor did the Greenham Women interact much with the American troops who worked in the compound. When there was combat, it was between fellow citizens, between the protestors and the police or bailiffs, or between others sympathetic to either one side or another. One woman described the locals of Greenham with contempt as exuding a ‘kind of deferential, cap-touching Toryism’.4 The villagers were angry about the encampment, as were many of their magistrates, councillors and judges. Stories were passed from woman to woman along the pathways encircling the base, of local men lurking in the brambles ready to pounce or gangs of lads pouring sacks of cement into their tanks of drinking water. Even among the women various tensions flared up, usually between those with more radical and separatist impulses, against those with careers, husbands and children to factor into their plans. Yet another battleline surrounded the camp; that between men and women. This is the most primordial division of them all, a boundary always assumed until recently to be the most insurmountable.

Looking at this episode of history now, certain things command our attention. The command is heard all the more forcefully because the official chroniclers of Greenham have been so inattentive. Looking at history with your eyes firmly focused upon it makes your own time look different when your gaze turns back. Glance at history lazily and your eyes will never see the horizon beyond your own. Then history affirms the status quo, the boundary between then and now is just as expected, not fuzzy and unreal as your eyes adjust to something new. But Greenham does not just ratify the values of today, there are times when it also revokes them. That is, this episode shows a clear intersecting of things today’s culture wars cannot countenance as belonging together.

Today’s identitarian feminists would struggle particularly with Greenham’s celebration of natality, of the primordial commonality between mother and child. Those who hold that defining womanhood through life-giving capacities is but an outdated remnant of obedience to the patriarchy only see things from the other side of a broken binary. Their eyes cannot be focused on those moments when such things were held in common. If the duties of motherhood are always enslaving, women’s liberation is freedom from procreation. But, to look attentively means that behind the permitted voices hover the remnants of very different experiences – suspended along the horizon, out of focus, some distance away – the wire fences holding our contemporary maladies in place disappear, leaving only the colourful expressions of a more innocent time. Greenham is striking today because many of these women went into battle precisely because they saw themselves as the handmaidens of life on Earth, by virtue of being women.

The quote given above from a mother moved to political activism after she was ‘sat in front of the television, my one-year-old in my arms, my heart sinking with fear’ is but one example. The bind between mother and infant unbinds her energies to be expressed in political action. The name ‘Women for Life on Earth’ would today seem more natural for a pro-life group than a feminist organization. The similarities do not end here. One of the original leaflets for this group asks ‘Why are we walking 120 miles from a nuclear weapon facility in Cardiff to a site for Cruise missiles in Berkshire?’ On the back was a picture of a baby born dead, killed by the radiation from Hiroshima, saying ‘This is why.’5 At least one key player in setting up the camp was a midwife. Welcoming and integrating mothers with children and babies was a sine qua non of it being a space for women, a place where the demands of motherhood could be genuinely welcomed by those upon whom such demands are ever laid.

Natality informed the rationale for a distinctively women’s peace movement: ‘because I am a woman I am responsible’, said one.6 Dora Russell wrote that peacemaking is a natural extension of a feminine genius: ‘If differences are not to be settled by war but by negotiation, there must be more feeling for cooperation’, she says, and ‘[w]ithin a family, a wife and mother traditionally tries to reconcile differences’.7 She points out that there was a broad spectrum involved in the movement, including some who, like today’s dominant voices, considered a focus on procreative capacities to be symptomatic of male oppression. But this doesn’t detract from the fact that keeping our eyes firmly fixed on this episode makes it clear that a great many involved in Greenham Common would be unwelcome in feminist political activism today. They would be cancelled and endlessly trolled as conservatives or reactionaries.

This side to Greenham is a story very few of its contemporary admirers are likely to tell. But, as Russell stated in 1983, ‘there are large numbers of women who felt compelled to act because of the traditional roles in which they found themselves’.8 The group Babies Against the Bomb was founded by Tamar Swade, who describes early motherhood as joining ‘a separate species of two-legged, four-wheeled creatures who carry their young in push-chair pouches’ and who occasionally ‘converged for a “coffee morning” or a mother-and-baby group run by the National Childbirth Trust’. At these gatherings, there would be ‘much discussion about nappy-rash, (not) sleeping and other problems pertaining to the day-to-day survival of mother and infant’. The thinking behind Babies Against the Bomb led directly from these most motherly of concerns – ‘Why not start a mother-and-baby group whose discussions included long-term survival?’ she asks. For ‘[t]hrough my child the immorality of this world … has become intolerable’.9