Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Unicorn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

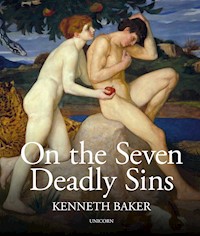

In this fascinating book Kenneth Baker explores how the Seven Deadly Sins – Pride, Anger, Sloth, Envy, Avarice, Gluttony and Lust – have shaped history from the Greek and Roman Civilisations, through their heyday in the Middle Ages, when sinners really believed they could go to Hell for all eternity, to the secular world of today, where they are still an alluring and destructive force. Today most sinners are punished in this world not the next: • Black Pride and Gay Pride have made tens of millions more understood and more accepted, but the overweening pride of certain leaders – Hubris – has led to wars and devastation: Hitler in Russia; the Japanese at Pearl Harbour; Saddam Hussein in Kuwait; and Blair and Bush in Iraq. • Anger, when righteous, can be a virtue, which helped to end the slave trade in the 19th century and to expose child abuse today, but there is still personal anger in domestic violence and Daesh terrorism. • Sloth can be an amiable weakness as Tennyson said, 'Ah why should life all labour be', but the rewards go to the energetic. • Envy is the mainstay of the global advertising industry encouraging everyone to improve their lives, but it is also a secret vice, a self-destroying morbid appetite. • Avarice, has led to better living conditions for many people but also to the Great Depression, the financial collapse of 2008, and to 1,800 billionaires with the combined wealth of US $6.48 trillion. • Gluttony is not a sin but a destructive ailment leading to obesity, bottle-noses, bleary eyes, grog-blossoms and breath like a blowlamp. • Lust that demands immediate gratification is clearly still a sin, whether Paris' abduction of Helen of Troy, or websites that encourage marital infidelity, or the fate of many politicians, as Kipling said, 'For the sins they do by two and two, they must pay for one by one.' This book is lavishly illustrated from Medieval manuscripts to Picasso, and Kenneth Baker has drawn on his knowledge of cartoons down the ages to include a few by Gillray, Rowlandson, Bateman, Eric Gill and today Peter Brookes.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 340

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A LITTLE TIGHTER, 1791 Thomas Rowlandson (1757–1827) Hand-coloured etching

A LITTLE BIGGER, 1791 Thomas Rowlandson (1757–1827) Hand-coloured etching

There is a charm about the forbidden that makes it unspeakably desirable. MARK TWAIN

On the Seven Deadly Sins

KENNETH BAKER

Dedicated to my book-loving grandchildren:Tess, Oonagh, Conrad, Evie, Fraser, and Stanley

It all started here…The Temptation of Eve, The Berners Hours, c. 1470

Contents

As literal madness is derangement of reason, so sin is derangement of the heart of the spirit, of the affection.

CARDINAL JOHN HENRY NEWMAN (1801–1890)

That deadly sin at doomsday shall undo them all.

Piers Plowman, WILLIAM LANGLAND (1370–1390)

He that once Sins, like him that slides on Ice, Goes swiftly down the slippery ways of Vice; Tho’ Conscience checks him, yet, those Rubs gone o’er, He slides on smoothly, and looks back no more;

Satire XIII, DECIMUS JUNIUS JUVENAL (c. 55 – c. 140) Translated by Thomas Creech

Introduction

IBECAME AWARE OF THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS RATHER LATE IN LIFE. We were evacuated from the Blitz in London to Southport where I was fortunate to go to a Church of England primary school, which gave me an outstandingly good education. Each day began with a hymn and a prayer, for that was normal in all schools, and we were taken to church twice a year. We did learn about what was right and wrong, for each day we asked God to ‘forgive us our trespasses’, though these were never called sins and there was no mention of Hellfire and damnation. Neither in my later education nor in the many sermons I have sat through did I hear any mention of them.

It was only when I began collecting political caricatures that I came to the realisation that the cartoonists’ victims were all being punished for their bad behaviour – ‘sins’. The purpose of a cartoonist is to capture the moment when something silly, stupid, malevolent, careless, wrong, wicked or evil is done by their victims and then to castigate, with humour, their folly and errors. The seven deadly sins were apt signposts for Gillray, Rowlandson and Cruikshank in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries to satirise those who had succumbed to pride, anger, sloth, envy, avarice, gluttony or lust, just as our contemporary cartoonists do today. Occasionally cartoonists want to recognise actions that are noble, courageous or right and portraying the seven virtues may be more suitable. But, in the struggle between sins and virtues, sins have the edge. Gerard Manley Hopkins reflected upon the unending battle against sin which he seldom won:

Why do Sinners’ ways prosper? And why must

Disappointment all I endeavour end?

…Oh, the sots and thralls of lust

Do in spare hours more thrive than I that spend,

Sir, life upon thy cause…

GERARD MANLEY HOPKINS (1844-1889)

Classifying and defining this panoply of bad behaviour and vice was started initially by philosophers and theologians, who made the seven deadly sins a central part of Christianity. Although this concept is rooted in that religion, other faiths that believe in an afterlife also teach ways to live in this world, for the benefit of their souls in the next.

In this book, I explore some aspects of the cultural history and western intellectual thinking on the seven deadly sins. I also try to show, how in today’s more secular society, these sins still have some significance and bearing upon our behaviour.

The seven deadly sins were first listed by Pope Gregory in the sixth century and up to the seventeenth century formed a core element of Christian teaching. During that time the faithful were taught that on the final day of judgement they would be weighed in the balance and if they were found to be sinners they would endure eternal punishment in Hell.

A demon with his cartload, Taymouth Hours, c. 1350.

After the sixteenth century Reformation, Roman Catholics accepted a much stricter doctrine of sin than Protestants, but maintained the same belief in Hell, though over the years there was much less concentration on it. In 1996, the Church of England, in a report approved by the Synod, decreed that the traditional images of Hellfire and eternal torment were outmoded and that Hell was a state of un-being.

However, in 2000, a report by the Evangelical Alliance, which was welcomed by the Catholic Church, urged Church leaders to present the Biblical teaching on Hell: ‘There are degrees of punishment and suffering in Hell related to the severity of sins committed on earth’ and that ‘those who through grace have been justified by faith in Jesus Christ will be received into eternal glory’, while those who rejected the Gospel will be condemned to Hell. For some Christians, Hell is still a very real punishment, but for many in our secular society, the horrors of Hell simply do not exist. To them, the punishment of sinners happens in this world, not in the next.

Hell by Dieric Bouts (detail), 1450.

Bernard Quaritch Ltd, Catalogue, 2016.

Since the Reformation, science, medicine and psychology have created a secular basis for morality and it is usually governments and not religions which make laws influencing people’s behaviour. Governments evaluate what is unacceptable, vicious or evil, and proceed to determine appropriate punishments for them. But, crime continues to rise in most countries throughout the world and politicians are slow to recognise that you can’t be tough on crime and tough on the causes of crime, without being tough on sin.

So, in today’s more secular society, have the deadly seven been relegated, surviving as a pub quiz question, or a feature in a weekend magazine, or as an amusing dinner party conversation? In 1995, the film Seven, starring Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman, was one of the highest grossing films of that time. In 2016, a leading London bookseller published a whole catalogue on the seven deadly sins, using them as a hook to sell books covering all manner of misbehaviours. In 2017, a Google search produced 1,240,000 results for the seven deadly sins. So, they do linger on, exerting a powerful attraction on human nature, which itself has not changed all that much over the centuries. People today are just as likely to succumb to one of the deadly seven as at any time in the past.

There is a little bit of each of these sins in all of us. We have all experienced occasions when we have been too angry, too greedy, too lazy and too proud, and found that guilt, shame, embarrassment or silent anguish have been our lot. Sins are often difficult to resist because in moderation they can be enjoyed with pleasure. Moreover, it is quite possible to enjoy such pleasure and not be tarnished by it. A sin becomes deadly when behaviour, which may appear to be natural, is transformed by obsession. Take greed for example. It is acceptable and socially necessary for people to work hard, be creative, innovative and competitive, to earn enough to feed and house their family, and to provide for their old age. However, the acquisition of money becomes a sin when it takes a person over and becomes an end in itself, transforming their personality and bringing in its wake another range of sins: selfishness, miserliness, deceit, deviousness, unscrupulousness and fraud. The same is true of lust. The physical attraction of a man and woman is essential for the continuation of the human race but if that turns into a preoccupation with sexual activity there are inevitable consequences, as Kipling wisely observed, ‘for the sins they do by two and two, they must pay for one by one’.

Many people, have argued that the deadly seven are not relevant to the most common personal failings and temptations in society. In, The Inferno, Dante added some more sinners to the list.

Is fraud, the latter sort seems but to cleave

The general bond of love and Nature’s tie;

So the second circle opens to receive

Hypocrites, flatterers, dealers in sorcery,

Panders and cheats, and all such filthy stuff,

With theft, and simony and barratry.

The Divine Comedy: The Inferno, Canto XI, DANTE ALIGHIERI (1265–1321)Translated by Dorothy L. Sayers.

Simony is the sale of clerical offices and Dante was accused of barratry (the practice of trafficking in public offices), and for that he was exiled from Florence. Today, other misbehaviours compete for recognition, including disloyalty, abuse of children, cruelty, racial or religious bigotry, corruption, treason and revenge. This newer list shifts the emphasis from personal failure to the mutual responsibility that we owe to others. It is indicative of how our moral thinking has developed from personal concern for human weakness to shared concern for the weakness of society in general, for which we may have some responsibility.

It is not just ordinary people who may succumb. The deadly seven can also affect the leaders of a country. In my lifetime I have seen numerous wars launched through their overweening pride or hubris, as the Greeks called it; Hitler launching the battle of Moscow, the Japanese attacking Pearl Harbor, General MacArthur invading North Korea, Saddam Hussein occupying Kuwait and George W. Bush, with his enthusiastic ally Tony Blair, invading Iraq. They all believed themselves to be insuperable champions, and they and the world paid for it.

Buddies in hubris – Adolf Hitler, preparing to invade Russia, and Japanese Foreign Minister, Yosuke Matsuoka, preparing to attack Pearl Harbor, March 1941.

Today ‘sins’ are multi-faceted with several interpretations. Pride, for example, can be both good and bad. Envy can lead to vicious and vindictive acts, but it can also be a driver to a better standard of living. Anger can be righteous and also unforgivable. Sloth can be wilful laziness but also an amiable trait. Gluttony can be an act of self-harm but it can bring much pleasure and enjoyment. Avarice can be selfish greed but great fortunes can lead to great philanthropy. Of them all, lust is always what it has been; a sin without a better side.

All orders of society have succumbed to lust, including the ‘high and mighty’, as Arthur Schopenhauer identified:

[Lust] is the ultimate goal of almost all human endeavour, exerts an adverse influence on the most important affairs, interrupts the most serious business at any hour, sometimes for a while confuses even the greatest minds, does not hesitate with its trumpery to disrupt the negotiations of statesmen and the research of scholars, has the knack of slipping its love-letters and ringlets even into ministerial portfolios and philosophical manuscripts.ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER (1788–1860)

I have therefore included in a later chapter two recent cases where distinguished British politicians, one from the House of Lords and one from the House of Commons, have been disgraced through lust.

I don’t think even Schopenhauer’s prescience could have foreseen what two American Presidents said after they had succumbed to this deadly sin. One admitted it and one tried to deny it:

I have looked on a lot of women with lust, I have committed adultery in my heart many times. This is something that God recognises I will do and I have done it and God forgives me for it.PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER interviewed by Playboy magazine, November 1976

I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky.PRESIDENT BILL CLINTON, January 1998

In 1996 it was rumoured that President Bill Clinton had had an affair with twenty-two-year-old, White House intern, Monica Lewinsky. At the time both she and Clinton denied having had sex in the Oval Office (dubbed the ‘Oral’ Office). But in August 1998, Clinton gave a nationally broadcast statement and admitted having ‘an improper physical relationship’. He was acquitted on an impeachment charge of perjury and obstruction of justice. The issue came back to haunt the Clintons when in the presidential election of 2016 Donald Trump embarrassed Hilary Clinton by parading several women who claimed that they had had an affair with her husband.

The Shag, Peter Brookes, 1998.

In my political life I have seen the consequences of indulging in one of the deadly seven, bring down Ministers and Members of Parliament:

• some brought down by pride and over-confidence

• some embittered by envy

• some angry at being passed over for promotion

• some seats lost through idleness

• some reputations destroyed by greed, both in and out of office

• some ruined by drink; and

• some ministerial careers ended through lust.

But do not think for a moment that MPs are more susceptible to sin than their constituents. Any group of people, who work or play together and compete with each other will be subject to the temptations of the deadly seven, whether in a business company, a tennis club, a university faculty, a newspaper group, a sporting team, or a trade union.

In this brilliant cartoon by Peter Brookes, the virtuous Theresa May enters No.10 stepping over the dead bodies of her rivals, each of whom was brought down by one of the deadly seven. I leave it to you Dear Reader to decide the different sins to which Boris Johnson, Andrea Leadsom, Michael Gove, Stephen Crabb and David Cameron succumbed and I hope you will be helped in making that decision from the many incidents in this book, and indeed from what you will be able to draw from your own experience.

Red Carpet Treatment, cartoon by Peter Brookes, 2016.

A short history

THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS ARE: PRIDE, ANGER, SLOTH, ENVY, AVARICE, GLUTTONY AND LUST. The first five are spiritual and the final two carnal sins.

Although no list of these sins appears in either the Old or New Testament, Biblical antecedents exist. The Book of Proverbs: Chapter Six, states that the Lord specifically regards, ‘six things doth the LORD hate: yea, seven are an abomination unto him.’ Ancient precedents for the seven deadly sins can also be found in Greek and Roman culture. These, however, concentrate on stories of the weakness of human nature in terms of the struggle between vices and virtues but not as sins explicitly.

In classical Greece and Rome individuals who chose to sin came to very sticky ends but their punishment was meted out in this world and not the next. Early Christians adapted such Greco-Roman thinking and put the concept of sin at the very centre of their religion. Sin was usually regarded as an attitude of defiance or hatred of God. In their zeal to convert people they taught that the punishment for sin was an everlasting torment in the next world. Hell was no longer a mythical place; it was the real destination of the damned, who would be eternally tormented by demons. Among the Apostles to teach the Gospel of Christ in the first century, St Paul affirmed that all men are implicated in Adam’s sin: ‘Therefore, as by one man sin entered into the world, and death by sin, so death passed onto all men, for all have sinned.’

St Augustine, in the third century, made use of this idea in developing his own doctrine on Original Sin. He took the view that the sin of Adam was inherited by all human beings and transmitted to his descendants. This concept has been embraced by some and totally rejected by others as a monstrous perversion of God’s will.

Shortly before St Augustine achieved renown for his ideas on Original Sin, St Anthony became a leading father of Christian monasticism for his legendary combat against the Devil and temptation. According to his biographer, Athanasius, he spent thirteen years in the western desert of Egypt resisting the temptations of the flesh, food and lust, through prayer and fasting. Alone in the desert there was nothing to be angry about, no one to envy, virtually nothing to covet, little to be proud of and no place for laziness. But the carnal sins of the flesh were ever present.

The Devil presenting Saint Augustine with The Book of Vices, Michael Pacher, 15th century.

Evagrius of Pontus, another desert father living in the third century, was the first to formulate a list of sins based on various forms of temptations. Intended for self-diagnosis, the list led by gluttony, contained eight sins: gluttony, lust, avarice, sadness, anger, sloth, vainglory and pride. Pope Gregory the Great, at the end of the sixth century, modified Evagrius’s list by merging sadness with sloth, dropping vainglory and introducing envy. Establishing that these sins were the worst vices separating a person from God’s grace, he ranked them based on the degree from which they offended against love. Pride was the most serious offence and lust the least.

The Torment of St Anthony, Michelangelo, c. 1487–1488.

Gregory took sins out of a strictly monastic context and set them right in the centre of Christian teaching. This classification spread quickly through the early Christian Church. It became a simple and easily understandable way to instil the practice of good behaviour in the unlettered congregations across Europe. Everyone from the mightiest kings to the lowliest of peasants was reminded of the punishment of eternal damnation if they succumbed to temptation.

Although the Devil or Satan tempted Christ in the wilderness, his emergence as the ruler of Hell and indeed Hell itself as the penalty for sinning was largely a creation after the sixth century. Up until then the Devil appears in the Bible and other sources under many guises, both human and divine, to challenge men’s faith. There is, however, no standard depiction of the Devil before the sixth century when Pope Gregory, having defined the deadly seven, urged his bishops to use iconography, sculpture, poetry and literature to spread the Christian message. The Mystery Plays, Chaucer’s poems, Dante’s Inferno and Milton’s Paradise Lost created vivid and memorable pictures in which sinners were roasted, frozen, flogged by horned fiends with heavy whips, branded with irons, cut with sharp knives, plunged into vats of boiling oil or lead, gnawed by dogs, rats, savaged by boars with deep fangs and strangled by snakes. Satan ruled in his underworld assisted by a whole army of devils with cloven hooves, horns and reptilian wings. The exact number was a subject for debate. In 1467, a Spanish bishop, Alfonso de Spina, calculated that there were 133,366,616 demons, but a Dutch demonologist a century later reduced this to 4,439,556.

In visual art, Giotto, Memling, Brueghel, Hieronymus Bosch, Dürer, Cranach, Tintoretto and Fra Angelico all produced large, vivid pictures of the horrors that would befall the sinful. Medieval churches carried images of the damned in stained glass windows, in the capitals of columns, in tympanums over the doors of churches and cathedrals. The dangers of sinning were embedded in society. Across Western Europe superstition was manifest and witches, who were regarded as the agents of Satan on earth, were frequently tried and burnt at the stake.

Although the highly influential theologian Thomas Aquinas, contradicted the notion that the seriousness of the seven deadly sins should be ranked, they became the focus of considerable attention within the Catholic Church in the Medieval period, as either venial or mortal sin. They were classified as deadly not only because they constituted serious moral offences, but, also because they triggered other sins and further immoral behaviour. Delivering and saving humankind from such fundamentally negative conditions was offered to those willing to love one another and make a commitment to be good. Given such circumstances, medieval scholars produced guidebooks to serve as manuals for confessors.

Stained-glass Demon, St Mary’s Church, Fairford, England, c. 1520.

Salvation was a bribe to be good. Archbishop Peckham, at the end of the fourteenth century, instructed priests to speak to their parishioners about the seven deadly sins at least ‘four times a year’ in the ‘vulgar tongue’ rather than Latin, the language of the sacraments. As far as the secular authorities were concerned the deadly seven were an effective way to persuade the lawless to behave and so bolster the coherence of society.

Satan visiting a man on his deathbed, French miniature, c. 1300.

The Powers of the Cross Protect Saint Anthony, Tom Morgan, 1996.

For all Christians, the prospect of being tormented in Hell by demons and serpents was a real possibility. The Devil was always scheming to tempt men and women to commit sins so that he could win their souls. He went under numerous names and was assisted by a whole galaxy of fallen angels: as Lucifer, the angel chosen by God, he was given the whole earth before he usurped God’s seat and was thrust out from Heaven; as Satan, the Prince of Darkness, who collected souls in his sack; as Mephistopheles, the subtle seducer of man’s vanity; as Belial, the arch-fiend whose sole occupation was the garnering up of sinners, he assumed various cunning disguises often as a serpent or confidant. As if fear of the Devil was not enough, Christians were also taught about the Last Judgement; the day at the end of time when God would decree the fates of all humans according to the good or evil behaviour of their earthly lives.

The Tympanum of the Cathedral of Autun.

One of the most dramatic sculptures of the Last Judgement is over the west door of the Cathedral of Autun in Northern Burgundy, later described by Malreaux as ‘an epic of Western Christendom’. This tympanum depicts Christ in majesty with St Peter on his right, with angels welcoming the saved souls, and on the left the cloven-hoofed Devil assisted by the Archangel Michael weighing the souls of the damned on a great scale, with those found wanting consigned to Hell. The sculptor of this dramatic carving was so proud that he actually signed his name under Christ, ‘Gislerbertus Hoc Fecit’. In the eighteenth century Voltaire jibed at its crudity and in 1766, in a fit of political correctness, the priests of Autun plastered it over and it remained concealed until 1948. This meant that when Talleyrand, Autun’s most famous bishop and a well-practiced sinner, made his one and only visit to the city in 1786 he would not have seen it; a disappointment for the Archangel Michael.

The Medieval mind was obsessed with the torment of Hellfire. Nowhere is this more evident than in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales where all the pilgrims believe in God, an afterlife, and the possibility of endless torture in Hell. The Tales, which include individuals who sin, make a homily on the dangers of sloth, avarice, gluttony, pride, anger, envy and lechery. Many of the Pilgrims travelling to Canterbury are directly involved in the church’s mission to save souls including the Prioress, the Second Nun, the Friar, the Monk, the Nun’s Priest and the Parson. Also included, operating on the periphery of the church, are the Pardoner, who sells indulgences, and the Summoner, who brings sinners before the ecclesiastical courts. All these pilgrims are supposed to be fighting the Devil and his works; a battered and war-weary army formed up against the deadly seven.

The Medieval church used the deadly seven not only to tighten its grip but also as a source of tax revenue. The Confessional was not enough to secure true forgiveness and so the church sold indulgences by which forgiveness was bought for cash. These were ‘get-out-of-purgatory-free’ cards. It was this tax gathering that led Martin Luther, a German priest, in 1517, to hammer his ninety-five theses on the door of a Wittenburg church, shattering the certainty and unity of Christianity.

The Reformation, which Luther initiated, changed everything, for it attacked the whole ‘mumbo jumbo’ which had been so carefully constructed around the deadly seven. The authority of the Roman Catholic Church was challenged by individualism and personal choice. Protestantism, as it developed, condemned immoral behaviour, but adopting a rigid line on personal sins was not at its core. The emerging Protestant traditions of Luther and Calvin and their doctrines on sin influenced the Anglican Church which settled for the simple words of the Anglican Confession: ‘We have left undone those things which we ought to have done and we have done those things which we ought not to have done and there is no health in us.’

YANLUO, KING OF HELL

This is a reminder that many other religions accept that there is an afterlife and there is punishment for those who have sinned.

In East Asia and Buddhist mythology Yanluo is the wrathful God who judges the dead and presides over Hell. He is known in every country where Buddhism is practised – China, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Bhutan, Mongolia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos. In Hinduism the God of the dead is Yama.

Scroll painting of Yanluo presiding over Hell. Chinese Late Qing Dynasty.

TO THE READER

Folly and error, avarice and vice,

Employ our souls and waste our bodies’ force.

As mangey beggars incubate their lice,

We nourish our innocuous remorse.

Our sins are stubborn, craven our repentance.

For our weak vows we ask excessive prices.

Trusting our tears will wash away the sentence,

We sneak off where the muddy road entices.

Cradled in evil, that Thrice-Great Magician,

The Devil, rocks our souls, that can’t resist;

And the rich metal of our own volition

Is vaporised by that sage alchemist.

The Devil pulls the strings by which we’re worked:

By all revolting objects lured, we slink

Hellwards; each day down one more step we’re jerked

Feeling no horror, through the shades that stink.

Just as a lustful pauper bites and kisses

The scarred and shrivelled breast of an old whore,

We steal, along the roadside, furtive blisses,

Squeezing them, like stale oranges, for more.

Packed tight, like hives of maggots, thickly seething

Within our brains a host of demons surges.

Deep down into our lungs at every breathing,

Death flows, an unseen river, moaning dirges.

CHARLES BAUDELAIRE (1821–1867)Translated by Roy Campbell, Poems of Baudelaire.

PRIVATE VICES – PUBLIC BENEFITS

In the eighteenth century, one outspoken defender of the seven deadly sins was Bernard Mandeville. He was born in Holland in 1670 and was trained as a doctor specialising in the treatment of disorders arising from hypochondria and hysteria. He settled in England in the 1690s and published various works challenging some of the most respected ideas concerning social morality and religious ethics. These became popular best-sellers. The work for which he is most remembered is The Fable of the Bees which was first published anonymously in 1705, and again in 1714 and 1723. In this intriguing and witty poem he argues that society needs evil and vice to keep it going because from them springs the wider prosperity of the nation.

Human society is likened to a beehive where instinctively busy bees improve life for all other bees by bringing the great benefits of economic activity, markets and social structures. Mandeville suggests that people work because of greed, and keep the law out of cowardice. Avarice, self-interest, envy, vanity and a love of luxury are such driving forces in life that they too can be harnessed into doing good. ‘Their crimes conspired to make ‘em Great’. This paradoxical poem became very popular and it anticipated the doctrine of Utilitarianism which valued acts on the basis of how happy they made people.

The edition of 1723 occasioned a great deal of critical comment and the Grand Jury of Middlesex condemned the book as a public nuisance. Mandeville rigorously defended his views offering to burn it in public if the jury could find anything that was profane, blasphemous or immoral in it.

The Orgy, Rake’s Progress, William Hogarth, 1733. Ten women were employed in the brothel favoured by Hogarth’s rake.

THE FABLE OF THE BEES

Thus every Part was full of Vice,

Yet the whole Mass a Paradice;

Flatter’d in Peace, and fear’d in Wars

They were th’Esteem of Foreigners,

And lavish of their Wealth and Lives,

The Ballance of all other Hives.

Such were the Blessings of that State;

Their Crimes conspired to make ‘em Great;

And Virtue, who from Politicks

Had learn’d a Thousand cunning Tricks,

Was, by their happy Influence,

Made Friends with Vice: And ever since

The worst of all the Multitude

Did something for the common Good…

The Root of evil Avarice,

That damn’d ill-natur’d baneful Vice,

Was Slave to Prodigality,

That Noble Sin; whilst Luxury.

Employ’d a Million of the Poor,

And odious Pride a Million more

Envy it self, and Vanity

Were Ministers of Industry;

Their darling Folly, Fickleness

In Diet, Furniture, and Dress,

That strange, ridic’lous Vice, was made

The very Wheel, that turn’d the Trade…

Thus Vice nursed Ingenuity,

Which join’d with Time; and Industry

Had carry’d Life’s Conveniencies,

It’s real Pleasures, Comforts, Ease,

To such a Height, the very Poor

Lived better than the Rich before;

And nothing could be added more.

BERNARD MANDEVILLE (1670–1722)

PRIDE

THE PRIDE OF THE NOUVEAURecovery of a Dormant Title or a Breeches Maker becomes a Lord Thomas Rowlandson, 1805.

Here we may reign secure, and in my choyce To reign is worth ambition though in Hell Better to reign in Hell: than serve in Heav’n.

Paradise Lost: Book I, JOHN MILTON (1608–1674)

Yes, I am proud: I must be proud, to see Men not afraid of God, afraid of me.

ALEXANDER POPE (1688–1744)

– E’en then would be some stooping; and I chose Never to stoop.

My Last Duchess, Section IV, ROBERT BROWNING (1812–1889)

Ante ruinam exaltatur – before destruction, the heart of man is exalted.

SAINT AUGUSTINE (354–430)

The devilish strategy of Pride is that it attacks us, not in our weakest points, but in our strongest. It is preeminently the sin of the noble mind.

DOROTHY L. SAYERS (1893–1957)

Pride has always been one of my favourite virtues. A proper pride is a necessity to an artist.

EDITH SITWELL (1887–1964)

The Fall of Icarus, Jacob Peter Gowy, 1636–38).

Icarus’s father Daedalus fashioned some wings from feathers and wax so they could escape from the Isle of Crete. Icarus was told not to fly too close to the sun as the heat would melt the wax, which is exactly what he did, and he fell to his death in the sea below. Pride came before the fall.

FOR MANY PEOPLE TODAY, PRIDE IS A VIRTUE to be cherished and not a sin to be resisted. Pride drives athletes to reach for the Olympic medal, students to strive for better results, football fans to follow passionately their team and soldiers to die for their country. Black Pride and Gay Pride have made tens of millions more understood and more accepted, and they have rolled back the tides of prejudice, bigotry and hatred.

However, the writers and philosophers of Classical Greece and the early Christian Fathers were in no doubt that pride was the most grievous sin, precipitating disaster and damnation. In Greek tragedy, arrogant mortals who defied and challenged the gods, displayed excessive pride, or hubris. Such behaviour was followed by peripeteia (a reversal of fortune) and ultimately nemesis (divine retribution). History is crammed with stories where this happens.

The Old Testament was crystal clear: ‘Pride goeth before destruction and a haughty spirit before a fall.’ St Augustine maintained that pride was the commencement of sin, for man’s judgement challenged God’s authority and it was this that led Adam and Eve to disobey and be cast out of Eden. Thomas Aquinas took a similar view saying it was pride that turned man away from God and was the source of all the other sins. It was Lucifer’s pride that drove him to abandon God in his Heaven. Milton, in Paradise Lost, beautifully captured this moment, giving Lucifer the famous phrase, ‘Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven’. Later in the twentieth century, C.S. Lewis also emphasised the overwhelming significance of this sin, ‘Pride leads to every other vice. It is the complete anti-God state of mind’.

Pope Gregory, in marshalling the list of the seven, put pride (in Latin superbia), at the top displacing gluttony, which had held that position in an earlier list. He condemned the arrogance of man ‘who favours himself in his thoughts and walks with himself along the broad spaces of his thought and silently utters his own praise’. This interpretation is still recognised as an essential element in many of the world’s religions but it also emerges strongly in the current debates on social policy. The opponents of abortion and of assisted dying believe that as God’s greatest gift is the granting of life, it is God who should decide when it should end, not proud man.

DR ROWAN WILLIAMS, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, an outstanding theological writer, scholar and teacher is quoted as saying:

The worst sin? No contest: it has always been seen as pride – that is the determination to put yourself at the centre of everything, to deny you depend on others and others on you; to behave as if you had the power to organise reality to suit yourself in every way. All the specific sins in matters of sex and money and personal relations and unfair structures, have their roots in this, one way or another.

The former Chief Rabbi, DR JONATHAN SACKS, takes a similar view:

Sin means doing what I want while ignoring what you want, pursuing my pleasure even if it causes you pain… Sin means listening to the I but not the thou.

The essence of the sin of pride is disobedience and when carried to the extreme, leads to rebellion. It should be noted that it is the only sin that has this consequence. There are many examples of this from the disobedience of Satan to God to the disobedience of Martin Luther to the Catholic Church. Disobedience and the elevation of self is a road with two forks. One that is good leads to self-esteem and one that is bad leads to arrogance, self-aggrandisement and vainglory. The suicide bombers of Daesh were so proud of their religion, their prophet, their sharia, their cause and their control of over five million people in the lands they once occupied, that they will vaingloriously video themselves before committing suicide.

There is also military hubris. Alistair Horne in his brilliant book, Hubris, shows how five wars in the first half of the twentieth century were caused by the overweening pride of leaders and countries convinced that they were invulnerable, racially superior and chosen to be victorious. Japan’s remarkable victory over Russia in 1905 created an illusion of racial superiority and military invincibility and opened the way to its attack on Pearl Harbor and the conquest of much of South East Asia. It also led to its nemesis with two atom bombs in 1945.

Similar hubris overtook Hitler when he decided to invade Russia and it overtook General MacArthur, who following his successful victory in South Korea, decided to cross the 38th parallel and invade North Korea. Disagreements over foreign policy in Korea led to him being sacked by President Truman, nicknamed the Missouri haberdasher. A further story of hubris rings true of Israel with its triumph in the Six Day War of 1967 and its nemesis in the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

BELSHAZZAR’S FEAST

The history of Belshazzar’s feast in 539 BC, which was recorded by Daniel and later put into verse by Chaucer, originated many years earlier after the capture of Jerusalem by the Assyrian King, Nebuchadnezzar. Over 10,000 Jews, including Daniel himself, Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego were abducted and placed in captivity in Babylon. The prophet Jeremiah prophesied that Judah’s captivity in Babylon would last seventy years. In that very year Belshazzar was co-regent of Babylon and his kingdoms were under attack by Cyrus the Great of Persia and Darius the Mede, who were extending their empire from the Indus Valley to the Mediterranean. Belshazzar supposed that the walls of Babylon were impregnable and in arrogant disdain he arranged a great feast and ordered that the sacred vessels, that had been seized from the temple of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar, should be brought to his table so that he, his wives and his concubines could drink wine from them. This blasphemous act was punished by a huge hand writing on the wall in Aramaic, ‘Mene, Mene Tekel Upharsin’, which was translated by Daniel, then an old man, foretelling the destruction of Belshazzar and his kingdom – ‘God hath numbered thy kingdom, and finished it. Thou art weighed in the balances, and art found wanting. Thy kingdom is divided, and given to the Medes and Persians.’ That night the forces of Cyrus and Darius burst through the city walls and killed Belshazzar, and after this victory they allowed the Jews to return to Jerusalem to rebuild their temple.

Belshazzar’s Feast, Rembrandt, c. 1636.

BELSHAZZAR

He had a son, Belshazzar was his name,

Who held the throne after his father’s day,

But took no warning from him all the same,

Proud in his heart and proud in his display,

And an idolater as well, I say.

His high estate on which he so had prided

Himself, by Fortune soon was snatched away,

His kingdom taken from him and divided.

He made a feast and summoned all his lords

A certain day in mirth and minstrelsy,

And called a servant, as the Book records,

‘Go and fetch forth the vessels, those,’ said he,

‘My father took in his prosperity

Out of the Temple of Jerusalem,

That we may thank our gods for the degree

Of honour he and I have had of them.’

His wife, his lords and all his concubines

Drank on as long as appetite would last

Out of these vessels, filled with sundry wines.

The king glanced at the wall; a shadow passed

As of an armless hand, and writing fast.

He quaked for terror, gazing at the wall;

The hand that made Belshazzar so aghast

Wrote Mene, Tekel, Peres, that was all.

In all the land not one magician there

Who could interpret what the writing meant;

But Daniel soon expounded it, ‘Beware,

He said, ‘O king! God to your father lent

Glory and honour, kingdom, treasure, rent;

But he was proud and did not fear the Lord.

God therefore punished that impenitent

And took away his kingdom, crown and sword.

… ‘That hand was sent of God, that on the wall

Wrote Mene, Tekel, Peres, as you see;

Your reign is done, you have been weighed, and fall;

Your kingdom is divided and shall be

Given to Persians and to Medes,’ said he.

They slew the King Belshazzar the same night,

Darius took his throne and majesty,

Though taking them neither by law nor right.

My lords, from this the moral may be taken

That there’s no lordship but is insecure.

When Fortune flees a man is left forsaken

Of glory, wealth and kingdom; all’s past cure.

Even the friends he has will not endure,

For if good fortune makes your friends for you

Ill fortune makes them enemies for sure,

A proverb very trite and very true.

Canterbury Tales,GEOFFREY CHAUCER (1343–1400)

CORIOLANUS

‘What’s the matter you dissentious rogues’

Gaius Marcius was the great Roman general who was given the name Coriolanus after he had driven the Volscians from the town of Corioli. But, in the first scene of the play, even before the battle, he shows his utter contempt for the ordinary plebeians of Rome.

Mar. Thanks. What’s the matter, you dissentious rogues,

That rubbing the poor itch of your opinion,

Make yourselves scabs?

First Cit. We have ever your good word.

Mar. He that will give good words to thee will flatter

Beneath abhorring. What would have, you curs,

That like nor peace nor war? The one affrights you,

The other makes you proud. He that trusts to you,

Where he should find you lions, finds you hares;

Where foxes, geese: you are no surer, no,

Than is the coal of fire upon the ice,

Or hailstone in the sun. Your virtue is

To make him worthy whose offence subdues him,

And curse that justice did it.

Who deserves greatness

Deserves your hate; and your affections are

A sick man’s appetite, who desires most that

Which would increase his evil. He that depends

Upon your favours swims with fins of lead,

And hews down oaks with rushes. Hang ye! Trust ye?

With every minute you do change a mind,

And call him noble that was now your hate,

Him vile that was your garland…

Act 1, Scene 1,