Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

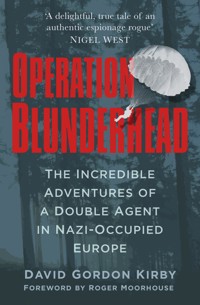

In the autumn of 1942, British Special Operations Executive agent Ronald Sydney Seth was parachuted into German occupied Estonia, supposedly to carry out acts of sabotage against the Nazis in a plan code-named Operation Blunderhead. Uniquely, it was Seth and not the SOE who had engineered the mission, and he had no support network on the ground. It was a failure. Captured by Estonian militia, Seth was handed over to the Germans for interrogation, imprisoned and sentenced to death, but managed to evade execution by convincing his captors that he could be an asset. What happened between Seth's capture and his return to England in the dying days of the war reads, at times, like a novel – inhabiting a Gestapo safe house, acting as a stool pigeon, entrusted with a mission sanctioned by Heinrich Himmler – yet much of it is true, albeit highly embellished by Seth, who was quite capable of weaving the most elaborate fantasies. He was an unlikely hero, whose survival owed more to his ability to spin a tale than to any daring qualities. Operation Blunderhead is a compelling and original account of an extraordinary episode of the Second World War – a brilliant blend of fact and fiction, contrasting material taken from SOE and MI5 files with Seth's own fantastical story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 419

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Acknowledgements

Following the career of Ronald Seth has led me down a number of interesting byways, and I wish to express my gratitude for their assistance to the following people:

Pekka Erelt, Meelis Maripuu, Malle Kiviväli, Helga Riibe and Andres Kasekamp for their advice and expert knowledge on matters Estonian; Axel Wittenberg for delving into the Militär-archiv in Freiburg; Philip Pattenden, whose information on Seth’s undergraduate days was invaluable; Blair Warden and the Literary Estate of Lord Dacre of Glanton for allowing me access to the correspondence between Seth and Hugh Trevor-Roper; Patrick Salmon and Tom Munch-Petersen for long years of friendship and shared expertise on northern Europe; and a special thanks to Laurie Keller, whose genealogical expertise and constant support has both assisted and inspired me.

Contents

Title

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Roger Moorhouse

1 ‘I thank God for one thing: I can still laugh.’ Paris, August 1944

2 ‘Circumstances which are both interesting and novel.’ London, October 1941

3 ‘Entirely satisfactory.’ Birkenhead, March 1942

4 ‘A little tin god.’ Tallinn, March 1936

5 ‘It seemed to me that the bottom had completely fallen out of things.’ Kiiu Aabla, Estonia, October 1942

6 ‘Then I fell forward.’ Tallinn Central Prison, November 1942

7 ‘I’m afraid they don’t like you.’ Gestapo Headquarters, Frankfurt-am-Main, February 1943

8 ‘For me, “practical love” is a physical necessity.’ Paris, March 1944

9 ‘Lately I have been in a depressed state of mind.’ Oflag 79, Brunswick, October 1944

10 ‘An occupation for gentlemen of high social standing.’ Berlin, Easter 1945

11 ‘Seth is mental.’ Bern, April 1945

12 ‘I clean buttons very well.’ Barnstaple, June 1945

13 ‘An extremely serious business.’ Reading, Christmas 1946

14 ‘Still drawing considerably on my imagination.’ Kiiu Aabla, September 2014

Bibliographical Note

Bibliography and Sources

Plates

Copyright

Foreword

by Roger Moorhouse

For a long time, when we thought of Britain’s wartime Special Operations Executive (SOE), the image that most probably sprang to mind was something akin to James Bond: the cold-eyed, ruthless assassin or saboteur, stalking occupied Europe and striking fear into Nazi hearts. There was something in this, of course. SOE – instructed by Winston Churchill to ‘set Europe ablaze’ in 1940 – scored some notable successes, most famously assassinating Himmler’s deputy Reinhard Heydrich in 1942 and sabotaging German efforts to make ‘heavy water’ at Vemork in Norway the following year. It even made plans to assassinate Hitler himself.

But, for all their dashing and their derring-do, SOE agents were not all James Bond clones. They were, instead, an eclectic bunch: men and women, drawn from many nationalities and all walks of life, encompassing everyone from safecrackers to bankers, secretaries to princesses. Clearly, the stereotype of the chisel-jawed action hero is one which requires substantial revision.

Yet, even bearing all of that in mind, the story of Ronald Seth is still a remarkable one. Seth, a 31-year-old former schoolteacher, was parachuted into German-occupied Estonia in the autumn of 1942 ostensibly to carry out acts of sabotage in a plan code-named Operation Blunderhead. It was a very rare example of a ‘privateer-SOE mission’, as the idea had come from Seth himself – then a humble RAF officer – rather than being dreamt up from within SOE. Moreover, unlike the vast majority of SOE missions, Seth had no support network on the ground at his destination; though he knew the country well, he was essentially going in ‘blind’. This combination of factors might well account for the peculiar choice of name given to the operation: perhaps someone within SOE was thereby expressing their concern about the mission’s feasibility.

In the event, such concerns would be amply borne out. Swiftly captured by local Estonian militiamen and handed over to the Germans, Seth was initially scheduled for execution before persuading his captors that he might be of some use to them. He then embarked on a remarkable odyssey across Europe, surviving on his wits, by turns seducing and frustrating his German captors. Finally, he was sent over the Swiss border, in the dying days of the war, apparently on a mission from Himmler to secure a separate peace with the Western Allies.

Seth’s story – full of pseudonyms, mistresses, aristocrats and double dealing – is one that almost seems to have sprung from the fraught imagination of a penny novelist. Yet it is true. Nonetheless, Seth was clearly not above embellishing it, both at the time and in his later memoir. His penchant for spinning a yarn, it seems, was irresistible. He told his German captors, for instance, that he knew Churchill personally, and that he was involved in a movement to restore Edward VIII to the throne.

To some degree, of course, such invention was an essential part of the game of survival that Seth was playing with the Germans. Many prisoners before him had made out that they were well connected so as to save their lives or even just secure better treatment; among them commando Michael Alexander, who claimed upon capture to be related to Field Marshal Harold Alexander, and Red Army soldier Vassili Korkorin, who passed himself off as Molotov’s nephew. At first glance, then, it might seem that Seth was merely following in that necessarily mendacious tradition, saving his own neck by making himself appear to be someone who might be of value to Berlin.

Yet, there is more to Seth’s story than meets the eye. For one thing, beyond the requirements of self-preservation, he seems to have embellished his own account of his exploits at almost every turn, adding details, vignettes and narratives that he borrowed from others, or else dreamt up for himself. Little wonder, perhaps, that SOE would later consider him to be royally unreliable, and – tiring of his Walter Mitty-ish excesses – brand him as ‘extremely untruthful’ and seek to stop the publication of his post-war memoir.

More importantly, perhaps, away from the hyperbole of his later memoir account, it seems that Seth may have played his wartime role of the ‘person of interest’ rather too well, straying over the line that divides self-preservation from active collaboration. Certainly there were more egregious examples than his own, and there was never sufficient evidence for any legal case against him to be mounted, but nonetheless Seth sailed rather close to the wind. Immediately after his capture, for example, he was already stressing his anti-Soviet credentials and offering to work for the Germans against Moscow. In time, he would inhabit a dubious Gestapo safe house in Paris and act as a stool pigeon in a British POW camp, informing on his fellow prisoners to the German authorities. Finally, he would graduate to the most exalted role of all: that of Himmler’s supposed emissary to London.

David Kirby’s book is a fascinating examination of this complex, sometimes bewildering story. It is certainly a most impressive tale. Ill-starred as his mission was, it was no mean feat for Seth to have survived his capture in German-occupied Estonia in 1942. The murderous fate that other captured SOE agents suffered, such as Noor Inayat Khan or Violette Szabó showed what treatment he might ordinarily have expected. Yet, what followed – even if one strips away the mythology and half-truths – was truly remarkable.

Beyond telling that fascinating story, the book has additional merits. Firstly, the author – a former professor of history from London University – expertly applies his critical skills, forensically dissecting the myriad layers of exaggeration, secrecy and obfuscation that have enveloped Seth and his tale almost from the beginning, sorting the plausible from the improbable. This is an important task. Historians, like seasoned investigators, always seek corroborating documentary evidence, but in Seth’s case it is more vital than ever.

The second merit is that, whilst rigorously applying those formidable investigative skills, Kirby’s is nonetheless a sympathetic approach. He views Seth as a curiosity, someone who – though he might have straddled the boundary between dissembler and fantasist – is nonetheless worthy of serious study and objective assessment. Moreover, as he notes at the end of the book, Seth seems to have had a ‘curious persuasive quality’, which made one want to believe him, ‘even if one is not always quite sure why’.

There are aspects of Seth’s story, one fears, that can perhaps never be satisfactorily clarified, but David Kirby’s skilful, sober study is a fitting epitaph to one of the most peculiar episodes of the Second World War.

Roger Moorhouse, 2015

1

‘I thank God for one thing: I can still laugh.’

Paris, August 1944

On the afternoon of 28 August 1944, Air Commodore H.A. Jones received a surprise visit in his Paris hotel room. Jones had served with distinction in the Royal Flying Corps during the First World War, and had taken up the role of official historian of the air force in the interwar years. He now held a senior rank in the Air Ministry with responsibility for public relations, and it was in that capacity that he had hastened to the French capital immediately after its liberation from Nazi German control. What the true purpose of his mission was is not clear, though he was soon plunged into the chaos and confusion of a city where thousands were eager to establish their credentials with the liberation forces, and thousands more sought to conceal their past actions.

Amongst those seeking to make contact with the Allied officers now hastily setting up makeshift quarters in the city were agents who had operated for months, even years, behind enemy lines. Air Commodore Jones had already encountered one of these men when he visited the hotel in the rue Scribe that had been commandeered by his staff. As he later described it, a pleasant looking, thick-set young man aged about 28 approached him, claiming that he had been dropped from a Halifax bomber over France in May, and asking to whom he should now report. It is perhaps a measure of the confusion that prevailed that Jones had to borrow a piece of paper in order to note down the man’s details (subsequent efforts in the Air Ministry to trace this man, who gave his name as Taylor, drew a blank).

No doubt relieved to leave behind the uproar at the Hôtel Scribe, Jones returned to his own quarters in the Grand Hotel, and was in discussion with an accompanying squadron leader when there was a knock at the door of his room, and another young man entered, saying that he would like to speak to Air Commodore Jones. This young man was described as dark-haired, thin, with a muddy complexion and rather beaky face. He spoke good English, but was obviously French. In his possession he had certain documents which he wished to hand over to the air commodore for transmission to London. The principal document was a handwritten report, which had been given to an intermediary, known only as ‘X’. ‘X’ had erased all references to himself in the report and had subsequently passed it on to the man who now stood in the air commodore’s hotel room. Further enquiry revealed the name of this young man to be Emile Albert Rivière, and his address as 56 avenue de Ceinture, Enghien-les-Bains. The writer of the report, who, according to Rivière, was now in the area of France controlled by the Germans, signed himself ‘Blunderhead’.

‘Blunderhead’ was the code name given by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to a mission to carry out a sabotage operation in German-occupied Estonia. The sudden reappearance of an agent who had not made contact since he took off for on this mission on 24 October 1942 was to cause some consternation in London, and not a small measure of embarrassment. Only one month before the report written and signed by ‘Blunderhead’ was handed over to Air Commodore Jones, the War Casualties Accounts Department in London had been informed that 68308 Flight Lieutenant Ronald Seth, reported missing on 21 June 1943, had now been classified as killed on active service on 24 October 1942. The accounts department was to take all action necessary, and was to note that Seth had been paid from other than RAF funds, that for the past five months his wife had received a remittance based on a weekly/monthly marriage allowance of 8 shilling and 6 pence, plus two-sevenths of a flight lieutenant’s pay and that payments from other than RAF funds were to cease with effect from 1 August 1944.

The term ‘payments from other than RAF funds’ is revealing. Seth had in fact been paid out of secret service funds since the end of 1941, when he was taken on by SOE, and he was the man whose report, dated Paris, 7 August 1944, finally landed on the desk of Major Frank Soskice, SOE’s Interrogation and Case Officer, some three weeks later.

Soskice, who was to pursue a successful political career after the war, serving as Home Secretary and Lord Privy Seal in Harold Wilson’s first government, interviewed Air Commodore Jones on his return from Paris, and managed to produce a succinct overview of the long handwritten report on the same day, 1 September. He concluded that there was no doubt that it had been written by Seth. The style of writing was unmistakeable, and it was in Seth’s handwriting. There was moreover a clearly identifiable photograph in the accompanying envelope that contained a letter in which Seth advanced his case for promotion to the rank of acting group captain (unpaid) with retrospective seniority. As for the narrative of events detailed in the report, Soskice was inclined to believe it to be true, though highly coloured and improbable in some of its details. He was clearly not unsympathetic towards a man who, he believed, had undergone many vicissitudes during his months of capture. ‘Seth is vainglorious in temperament’, was his conclusion ‘but it may be wondered whether his sufferings have not slightly unhinged his mind for the time being’.1

SOE had not been entirely in the dark about the fate of their agent. They had learnt in April 1943 that he had been captured in Estonia shortly after parachuting in at the end of October 1942, and had subsequently been interrogated by the Germans. A British agent had managed to photograph a number of German documents impounded by the Swiss authorities after two German aircraft had been forced to land in Switzerland, including an extract from this interrogation. From the description of the man under questioning, there could be no doubt that it was Ronald Seth. There was an initial worry that Seth’s wireless transmitter might be used to send false information, but surveillance was soon abandoned in view of the lapse of time since his capture. Operation Blunderhead was finally cancelled on 20 May 1943, and proceedings initiated to inform Ronald Seth’s wife, Josephine, that he had been killed in action, when the man himself resurfaced in France.

The initial response of SOE was commendably loyal, though there was evidently some uncertainty about what to do with an agent who still remained in German hands. Writing to Colonel T.A. (Tar) Robertson of MI5 on 25 September, John Senter, head of SOE security directorate, confirmed that SOE felt a responsibility to an agent who had undertaken a mission calling for great personal courage, as well as to the Air Ministry which had allowed him as a serving officer to be posted to SOE. Both men agreed that Seth ‘should not be treated on his return as a felon but as a British officer who must be invited to explain what had happened when he left this country’.2

Unlike certain known targets of interest to the security services such as Harold Cole, an army deserter who was actively collaborating with the Gestapo after betraying the Resistance network he had worked with, Ronald Seth’s presence in Paris had passed under the radar. The receipt of his report, written in an SS hospital in the Bois de Boulogne, thus unleashed a series of urgent enquiries about what Seth had been up to over the past eighteen months, and put the security services on alert for any possible attempt by the Germans to use him as an agent. Subsequent letters written by Seth in autumn 1944, after he had been confined to a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany, served only to sow more confusion about his mental health and his relationship with the Germans. The man who ended his long account of his trials and tribulations in various prisons across Europe with the bitter comment that he could thank God for one thing, ‘that I can still laugh’, was to have even more extraordinary adventures before he finally returned to British soil in the dying days of the war.

❖❖❖

What had happened to Seth between the time of his capture in the woods of Estonia in the autumn of 1942 and the liberation of Paris in August 1944, and what adventures he was subsequently to have before the end of the war is a fascinating story, but it is not always easy to establish the truth. His own account, published in 1952 with the title A Spy has no Friends, is a highly coloured version of events, and is often at variance with the evidence available in the archives, not least the reports he himself wrote at the time. His boundless self-confidence and lively imagination undoubtedly helped him survive captivity, but they also led him into exaggeration of his own importance and at times into telling downright untruths. He was a man with a heightened sense of his own importance, quite capable of weaving the most elaborate fantasies about his origins and his circle of acquaintances.

Fantastic though his account often is, there is sufficient independent evidence to support the veracity of the basic sequence of events which took him through a succession of prisons on a journey across Europe, to end up on the payroll of the German military secret service, lodged with a dodgy bunch of black marketeers and collaborators on the outskirts of Paris. In researching his story, I have on more than one occasion thought it too fantastic for words, only to be reminded by other sources of the old adage that truth can be stranger than fiction. It is hard to believe, for example, that a British prisoner being treated for scabies in an SS hospital would not only have the opportunity to write a neatly paragraphed and intensely detailed report of his activities on sixty-one foolscap pages, but would also be able to persuade a member of staff to post the document. It is equally difficult to understand why the recipient of the document, and the young man with the muddy complexion who delivered the package to a senior British representative should have willingly taken on this risk in the highly charged atmosphere of the dying days of the German occupation of Paris. The only plausible explanation must be that the Germans were so busy with preparations to leave the city that they had no time to bother about odd folk like Seth, whose credentials as a possible double agent had always been in doubt. It was perhaps Seth’s especial talent to sense this. In his ability to play along with the Germans, and their willingness to play along with him, it must also be said, lies the secret of his survival.

Unlike most of the men who ran SOE, Ronald Sydney Seth came from a humble background. His father Frederick was the son of a farm labourer from Northamptonshire who moved to London during the 1860s. If Frederick’s father, William, had hoped to better his prospects by moving to the city, these hopes appear to have been dashed. By the time of the 1881 census, the family had returned to the countryside, and William was once more working as an agricultural labourer. Ten years later, his 19-year-old son, Frederick, was living with relatives at Misson in Nottinghamshire, and working on the railways as a platelayer. Working on the railways was a classic way of escaping from the drudgery and impoverishment of farm labour, and Frederick took the opportunity. In 1901 we find him still living in Nottinghamshire, married with a young son, and employed as a railway signalman. Some time during the next ten years, Frederick left the railways and settled in Ely, where in 1911 – the year of Ronald Sydney Seth’s birth – he was working in the marine stores. Ronald’s mother died in 1916, and his father evidently remarried, for MI5 noted in 1945 that Ronald had a younger half-brother aged about 17 and a married half-sister. Ronald’s older brother, Harold Edward, was already working in the marine stores in 1911, and was in the employ of Marks & Spencer in 1942, the year in which his younger brother embarked on his Estonian adventure.

When Frederick died in 1940, aged 67, his occupation was recorded as ‘metal merchant’. Apart from a vague reference to some sort of business failure, Ronald did not say much about his father in his various personal statements. There was no inherited wealth, certainly: Ronald had to live on what he could earn. He was a boy chorister in the cathedral choir, and had attended the King’s School, Ely, described by one of its former pupils as having been run on a shoestring, with day boys paying only £6 a term.3 After completing his secondary education, Seth became a schoolmaster, teaching for a couple of years at Belmont House School in Blackheath, London, and for one year at the Bow School in Durham. At Belmont House he seems to have laid the foundation for what would become a further string to his bow in future years, though he gave no hint of this talent in his outline for SOE of his accomplishments. Unless Belmont House was a particularly enlightened and progressive school, the advice and instruction on sexual matters offered by the youthful novice master to his slightly younger charges could only have been given on the quiet.

It is not clear what Seth did after leaving his post at the Bow School. He later claimed to have studied at the Sorbonne, and he told SOE that he had spent a year visiting France, so this may explain the gap, though he replied ‘none’ when invited to give details of further education since leaving school on his application form for the RAF.

Amongst the details of his career submitted to SOE, Seth claimed that he had read English and theology at Cambridge University between 1933 and 1936. On his application form to join the RAF, he gave the dates of his Tripos examination as June 1933 and June 1938, which is inconsistent with the known record. The academic register of Peterhouse includes a Ronald Sydney Seth, elected in 1933 to a choral exhibition and a Morgan sizarship, and taking up residence at the college in the Michaelmas term of that year. The Morgan sizarship, worth £40 a year, was awarded to those who expressed a wish to be ordained in the Church of England. Ronald Seth’s first year seems to have passed uneventfully; he sat Part One of the English Tripos in the summer of 1934, managing a modest third, rowed in the third May boat, and was re-elected to the Morgan sizarship in the Easter term. But things were not going well for him, as is revealed in internal college correspondence from October 1935. He had been very unsettled for some time, and had finally confessed in the Easter term 1935 that he had lost his sense of vocation and would not now be offering himself for ordination. Instead, he was now very interested in social work, and would like to take up a job in that area as soon as possible. It so happened that a man had visited Cambridge to give a talk to undergraduates about the Borstal system, and as a consequence, Seth had successfully applied for the post of housemaster in one of the Borstal institutions. ‘We did our best to keep him here for his third year so that he could complete his degree’, the unknown tutor writes, ‘but he refused to be kept. I understand that he married almost as soon as he went down.’4

The writer of the letter was, however, misinformed about Seth’s marital status. Ronald Sydney Seth had married a Cumbrian girl, Josephine Franklin, in the summer of 1934. Reading between the lines, it would seem that the necessity of concealing this marriage from the college authorities had been too much for a young man already beset with doubts about his suitability for the church. A letter dated 15 June 1935 from the secretary of the Ely Diocesan Board of Finance to J.C. Burkill, senior tutor at Peterhouse, expressing concern about ‘this young fellow and the unhappy developments that have taken place’, is a fair indication that the news of his marriage had already reached those who were helping to finance his studies.5

What happened to Seth in the months after he went down from the university is unclear, but at the end of November 1935, Mme Anna Tõrvand-Tellmann, the proprietress of the English College in Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, received a letter from Elena Davies of International Holiday and Study Tours, recommending ‘a charming young man of good family’ for the post of English master. A postscript asked if the post would be available after the new year, as the man in question had been offered a position under the Home Office, but for many reasons he preferred to go abroad chiefly for the experience. Mme Tõrvand-Tellmann, who had been let down by a Mr Blackaby, appeared keen to engage the multi-talented Mr Seth, though she had to admit the salary of £8–9 a month was not of an English standard, even though the cost of living was much cheaper in Estonia. After a further flurry of letters, we find the Seth family, with their 6-week-old son Christopher (who also bore the impressive names John de Witt van der Croote), travelling to Tallinn at the end of February 1936. The three years spent in Estonia were to change their lives in ways none of them could ever have imagined as they set sail on a cold winter’s day from Hay’s Wharf.6

Notes

1. Report on ‘Blunderhead’, 1 September 1944, HS9/1344.

2. Senter to Robertson, 25 September 1944, HS9/1344.

3. Patrick Collinson, History of a History Man, p.44. www.trin.cam.ac.uk/collinson.

4. Unsigned letter of 19 October 1935, Peterhouse Archives. Ansell 1971, p.36. In April 1936, Seth wrote to an unnamed tutor at Peterhouse requesting a certificate of attendance. An unsigned copy of that certificate in the college archive, dated 2 May 1936, gives the dates as October 1933 to June 1935. A copy of the certificate, also unsigned but dated 2 May 1936, in the archives of the English College, Tallinn, gives the dates as October 1932 to June 1935. TLA (Tallinn Town Archives) 52.2.2442.

5. A.P. Dixon to J.C. Burkill, 15 June 1935. Peterhouse Archives. I am indebted to Dr Philip Pattenden of Peterhouse for this information.

6. TLA-148.1.10. Seth himself, in a letter of 30 November, claimed four years’ teaching experience and nine months’ original research on Daniel Defoe, on which, with typical Seth modesty, he declared himself to be ‘an authority’.

2

‘Circumstances which are both interesting and novel.’

London, October 1941

Had it not been for one unusual quality, Ronald Sydney Seth might well have been ignored or politely turned down for special operations service. A tall, bespectacled fair-haired man of modest physical stature, he looked more fitted for the part of a cheery schoolmaster than that of a saboteur. In September 1939, he had returned to England with his family from Estonia, where he had taught English since 1936. According to his own published account, he spent several weeks job-hunting, and then joined the BBC as a subeditor of the daily digest of foreign broadcasts. Seth claimed that he subsequently went on to help create the Intelligence Information Bureau of the BBC monitoring services, rising to become Chief Intelligence Supervisor (Country). However, he found ‘the constant jockeying for advancement’ and infighting too much for him, and he resigned. His actual service record paints a rather more modest picture of his short BBC career, in which he advanced from subediting to assistant in the Intelligence Information Bureau, and ending as a supervisor at the monitoring unit based near Evesham. There is no trace of him as ‘senior supervisor’ (the grade he gave in his personal details submitted for scrutiny by the secret services in 1942), still less as chief supervisor, at the monitoring unit.1 In February 1941 he resigned from the BBC and volunteered for the RAF. After initial training, he was commissioned in the summer and assigned to intelligence work with Bomber Command. It seems that the rather humdrum routine of low-grade intelligence gathering failed to satisfy his lively mind, for on 28 October 1941, he wrote to Group Captain J. Bradbury at the Air Ministry outlining a proposal to undertake a mission to Estonia.

In his letter, Seth mentioned an unsuccessful approach he had made in March 1941 to the War Office, offering to go to Estonia. It is interesting to note that whereas Estonia in the autumn of 1941 was occupied by the country with which Britain had been at war for two years, namely Germany, in the spring of 1941, it was still at peace, albeit having suffered a forced incorporation into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics the previous summer. Seth had told the War Office in March 1941 that he wished to go to Estonia to find out what he could about Russian activities there. In the proposal he outlined in October, he was dismissive of the Russians’ abilities to set up and direct a resistance movement in Estonia, because they were seen there as potential enemies. Here, as in later correspondence from Seth, there is a strong antipathy to the Soviet Union. In spite of his own admission that his politics were ‘vaguely socialist’, Seth certainly had no feelings of sympathy with the country that had occupied a land he had come to love, and where he had many friends, some of whom had disappeared during the Soviet occupation.

Far stronger than his dislike of Soviet Russia, however, was Seth’s sublime self-belief. ‘I cannot say that it is with diffidence that I suggest that the only Englishman who might be successful in carrying out such a plan is myself’, he wrote to Bradbury. ‘I have the contacts; I know the country, inside out; I speak Estonian fluently.’2 His plan, though, was little more than a vague proposal to sound out the lie of the land and to try and set up some kind of resistance movement. Seth proposed taking over the identity of an Estonian sailor called Felix Kopti, whose brother Georg had been his former pupil. Seth had apparently been frequently mistaken for Georg during his time in Estonia and as the brothers bore a very strong likeness to one another, he hoped to be able to pass himself off as Felix. From the British authorities, Seth sought assistance in obtaining the necessary papers, a passage to Sweden, and £300; once in Estonia, he claimed, he would be self-supporting.

Seth’s proposal was passed on by Group Captain James (‘Jack’) Easton of Air Intelligence to 64 Baker Street, the home base of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The recipient noted that it ‘read interestingly’, and in forwarding the paperwork, asked ‘would you like to see the man who seems to have guts, or perhaps a girl friend in Estonia’. Seth was seen on 21 November and approval to employ him, subject to a satisfactory second interview, was sanctioned by the directors on 10 December. The second interview on 13 December was satisfactory, and an application was made to the RAF for his release and promotion to the rank of flight lieutenant, in view of the hazardous nature of the project. On 7 January 1942, he was seconded from the RAF. A salary of £600 a year tax-free, with effect from that date, was proposed, with the possibility of an increase once he proceeded to the field of operations.3

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) into which Seth now found himself recruited had come into being some eighteen months earlier, in the immediate aftermath of the disastrous military campaign in the Low Countries and France that had ended with the evacuation from the beaches of Dunkirk. It had not been an easy birth. Within the tightly knit world of the secret service, clandestine operations were regarded with some suspicion. ‘Dirty tricks’ were somehow felt to be ungentlemanly, a distasteful activity far inferior to the gathering and evaluation of intelligence. Admiral Sir Hugh Sinclair, head of the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) since 1923, had made a careful distinction between active operations in the field and the often painstaking work of gathering and processing intelligence. The man who succeeded him in 1939, Sir Stewart Menzies, also reasoned that the objectives of special operations (SO) were often at odds with those of secret intelligence (SI). SIS did set up Section IX, or ‘D’, in 1938 to plan and carry out clandestine operations, including sabotage, but the often grandiose ideas advanced by Laurence Grand, the head of Section IX, and his inability to control operational costs, caused disquiet. Menzies’ unwillingness to defend his own head of section at a meeting with Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax at the end of June 1940 opened up the field to others to try their hand at organising sabotage and psychological warfare.

An unlikely but crucial proponent of this kind of warfare was the newly appointed Minister for Economic Warfare, Hugh Dalton. A product of Eton and Cambridge, Dalton had pursued an academic career before entering Parliament in 1924, becoming a junior minister in Ramsay McDonald’s ill-fated second government in 1929. An expert in public finance, he was to serve as President of the Board of Trade in the wartime coalition government between 1942 and 1945, and as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Clement Attlee’s post-1945 Labour government. Dalton’s working life was thus far removed from the world of espionage and secret operations; yet he had had military experience, serving on the French and Italian fronts during the First World War, and earning an Italian military decoration for his actions during the retreat from Caporetto. Some of this fighting spirit clearly inspired him to write to Halifax on 1 July 1940, urging the creation of ‘a new organisation’, comparable in its activities to Sinn Fein in Ireland or the guerrillas fighting the Japanese in China. Dalton was convinced that such an organisation could not be handled by the ordinary departmental machinery of either the civil service or the military. It would need absolute secrecy, fanatical enthusiasm and a willingness to work with people of different nationalities. Although some of these qualities were to be found in some military men, Dalton was quite clear that the enterprise should not be controlled by what he called ‘the War Office machine’.

An organisation created in accordance with these principles was bound to ruffle the feathers of the established bureaucratic order and military intelligence services, and so it proved. The Special Operations Executive (SOE) as outlined in a document handed over to Dalton on 22 July 1940 by the ex-Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, now Lord President of the Council, was to be outside parliamentary control, secret and inadmissible and all departments were required to assist it. In its six years of existence, SOE lived up to the ideals that inspired its creation, though by failing to put down any firm organisational roots it contributed to its own demise once war had ended. It had no central registry or filing system, and no head office: 64 Baker Street was little more a cover address.

In the dire situation faced by Britain in the months following military withdrawal from Europe, if not exactly setting Europe ablaze, as Churchill urged them to do, SOE did seem to offer a more pugnacious profile than the intelligence-gathering activities of SIS. Lord Selborne, who replaced Dalton in 1942 as Minister for Economic Warfare and as the government’s overseer of SOE, felt that, whereas SIS had initially seen SOE as a ridiculous and ineffective bunch of amateurs, they now feared them as dangerous rivals who, if not squashed, would soon squash them.

Although Section IX provided many of the key figures in SOE, others were also drawn in from City firms with strong international connections. There was indeed some suspicion and resentment that SOE recruited heavily through business networks. A not untypical example was George Odomar Wiskeman. Born in Sidcup, Kent, in 1892, and educated at Wellington and Corpus Christi, Cambridge, Wiskeman was a bachelor who had worked for many years in the timber trade. In January 1941, when he was recruited into SOE, he gave as his business address the timber importing firm Price and Pierce, and his residence as 13 Great James Street in Holborn. He claimed to have fluent Swedish and German, and ‘rusty’ Russian. He had lived for four years in Finland, and five in Russia as consular officer. MI5 described him as naturalised British, query Russian, which may indicate his father was a German-speaking Russian citizen, probably from the Baltic provinces.4

Wiskeman was ‘S’, head of the Scandinavian section of SOE in the autumn of 1941, and he was the man who handled the early stages of Seth’s application. Director of operations at SOE (‘M’) was Colonel Colin McVean Gubbins, KCMG, DSO, MC, a man with considerable experience of covert operations in north-eastern Europe. Gubbins had been a member of the British expeditionary force under General Edmund Ironside, sent to northern Russia at the end of 1918 to offer support to the White Russians fighting the Bolsheviks, and was appointed to the Russian section of the general staff research department of the War Office in 1931. In the late thirties, he undertook a rather secretive mission to the Baltic to investigate the possibility of organising anti-Nazi guerrilla units in the event of war. Gubbins had an extensive network of contacts in north-eastern Europe, and was able to draw upon the knowledge and expertise of a number of men with long-established business links in the area. The Russian revolution and the subsequent establishment of a communist regime had seriously disrupted business, in particular, the timber trade. Many of the leading figures in intelligence-gathering activities concerning Soviet Russia came from a timber trade background. A number of these men also had close links with various anti-communist networks, such as the Promethean League of Nations Subjugated by Moscow, and were involved in anti-Soviet campaigns such as organised in the early 1930s to challenge the import of Russian timber into Britain on the grounds that the use of forced labour in Russia was in contravention of the 1897 Foreign Prison-made Goods Act.5

As we have seen, Seth had tried to persuade the War Office to take up his ideas in the spring of 1941, but there is another odd piece of evidence which seems to suggest that he had been thinking as early as the spring of 1940 of trying to get to Estonia. In the course of checking his background for recruitment into SOE, a report from the Metropolitan Police was received by MI5. This stated that in May 1940, Seth had written to A.H. Harkness of Wimpole Street, a leading specialist in the treatment of urological and venereal complaints, ‘asking if it was possible to contract psoriasis in the national interest’. Interviewed by the police, Seth explained that the British government was desirous of getting somebody into Estonia, and that contracting this skin complaint would enable him to enter Estonia for treatment by means of the medicinal mud famous for its curative elements.6

If the date of Seth’s letter to Harkness is correct, then he was already contemplating a return to Estonia before it lost its independence. In the immediate aftermath of the infamous Nazi-Soviet Pact, concluded in August 1939, the three Baltic states had been obliged to conclude non-aggression treaties with the Soviet Union. These permitted the Soviet Union to station troops on Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian territory. Given that in his approach to the War Office in March 1941 Seth proposed to go to Estonia to investigate Russian activities, there is good reason to suppose that this may also have been his primary purpose a year earlier.7

How far was Seth’s evident desire to return to Estonia driven by anti-Soviet sentiments? That Seth did entertain such feelings was clear to the MI5 officers who interrogated him after his return to Britain in 1945. But although an urge to spy on Russian activities may have been his principal motive for wishing to go to Estonia before the summer of 1941, it seems less likely to have been the case after the Soviet forces had been driven out of the Baltic States by the end of August 1941 – unless he had in mind the creation of a resistance movement that might equally well operate against a returning Red Army.

As already indicated, there was within SOE a close-knit circle of friends and acquaintances who shared similar anti-Soviet views. These included Colin Gubbins, his close friend Harold Perkins, former owner of a textile mill in Poland, and Ronald Hazell, a former shipbroker with the United Baltic Corporation. Hazell appears as ‘Major Larch’ in Seth’s published account. Hazell was said to have an intimate knowledge of the Baltic States, and was deemed the man most suitable to superintend Seth’s training. In July 1941, Hazell had been put in charge of the section of SOE that dealt with Polish minorities, and Poland seems to have been the focal point of his Baltic expertise. Contacts with Estonians seem to have been left almost entirely to Seth to arrange, though Hazell was responsible for training and equipping him in conjunction with the operation orders drawn up by ‘S’, George Wiskeman. Seth clearly saw him as his friend and mentor; Hazell, who had to respond to Seth’s frequent complaints and enthusiastic suggestions, derived rather less satisfaction from the relationship.8

Estonia was not an area with which SOE had hitherto concerned itself, and care was taken to ensure that any operation was cleared with Moscow. SOE had in fact recently concluded an agreement with their Soviet counterparts on cooperation in subversive operations, a circumstance of which the writer of the cipher telegram sent to the British embassy in Moscow at the end of November was mindful. The telegram stated that SOE wished to send an agent to Estonia to carry out ‘a particular act of sabotage’. He would be fully instructed on his mission before departure, and would not communicate with London until he came out of Estonia. Since the agreement reached in September with the ‘Soviet organisation’ (the secret police, or NKVD) precluded British operations in the Baltic States, ‘please approach your Soviet colleagues and ask if we can have their permission to send in this man. You should make absolutely clear to them that we would under no circumstances act without their approval’.9 A week later, Moscow replied, saying that the Soviet side had no objection, and assumed that their assistance would not be required.

Details of the Estonia project were presented in draft form on 15 December. They went a good deal further than the ‘particular act of sabotage’ that was put up to the Russians as the objective of the mission. The operation was to have three main purposes. The first listed task was to organise and foment disaffection amongst the Estonian population and to promote friction between them and the Germans. The agent was also to carry out acts of sabotage at the shale-oil mines and refineries in the north-east of the country. Although it was recognised that their production levels were small even in European terms, the disruption of output would oblige Germany to supply Estonia with fuel, putting further strains on German transport. Finally, the agent was to carry out any other forms of sabotage, or passive resistance within his capabilities. The proposed date of the operation, which was given the code name ‘Blunderhead’ in mid-January, was March-April 1942. The operative, to be known in further internal correspondence as ‘Ronald’, was to be entirely alone, with no arms, equipment or ‘toys’. He was to assume the identity of an Estonian seaman. The drafter of the project fully accepted that it was conceivable that within three months, such an operation would no longer be feasible and would have to be abandoned, but at least SOE would have a fully trained operative for possible use in another field.10

This is essentially a reworking of Seth’s original idea, with rather little material commitment on the part of SOE. Under a false identity, Seth was somehow to make his way by sea to Estonia, and when there, organise a resistance movement and carry out acts of sabotage, presumably securing on his own initiative the necessary explosive and charges and any handy weapons.

The false identity that Seth was to assume was that of Felix Kopti, an Estonian seaman. Born in 1903, Kopti had spent many years on the world’s oceans. In April 1940, he had signed on as a seaman on SS Rugeley, but had jumped ship at Port Lincoln, South Australia some six months later. He appears as Craftsman Felix Kopti in a photograph taken in 1942 of a group of men of the 106 Independent Brigade Group Workshop, recruited largely amongst Victorians and South Australians, and was still living in Australia after the war.11

The bare details of the cover story for Seth, alias Felix Kopti, were in place by the beginning of March 1942. Details of recent shipping movements along the eastern seaboard of South America were gleaned, and in response to Major Hazell’s request for information on dockside brothels (‘as 90 per cent of a sailor’s conversation centres around this particular type of establishment’), names and addresses of choice locations and girls were provided.12 Having sailed the world for some two decades, most recently off the coast of South America, the fictitious Kopti was supposed to have succumbed to homesickness, and had stowed away on a Swedish ship, landing in Sweden. Stockholm was cabled on 11 March for information on the feasibility of smuggling Seth, masquerading as Kopti, into Estonia, either directly from Sweden, or via Finland. The response was not encouraging. There were no shipping communications between neutral Sweden and occupied Estonia, and the Germans were cutting down on marine communications from Finland.

The legation was also clearly worried about being compromised by seeking to obtain a Swedish visa for a purported Estonian returnee who was in reality a British agent. There had been a crisis in relations with the Swedish authorities in April 1940, when an SIS Section IX team working to sabotage Swedish port facilities handling iron-ore exports to Germany had been broken up and its leaders arrested. Both the minister to Stockholm and the head of the SIS station had taken this very badly, and were in consequence ultra-sensitive to any further involvement in clandestine activities on Swedish soil. Although the men in Stockholm continued to investigate the possibilities, they made little progress, and by the end of April, Baker Street had begun to think of an alternative means of getting Seth into Estonia: by air.

Whilst SOE had been casting around to find the best way to get him into Estonia, Seth had been undergoing training. On 22 April, writing from Morecambe, he reviewed his project in the light of the experiences of the past six months. He assumed he would now be delivered by aircraft, and that in view of the long daylight hours that are a feature of the northern European summer, such an operation would not be feasible until the end of October. He ruled out the possibility of taking supplies with him, since there would be no reception committee, nor any prearranged safe house. Any container dropped by parachute might come down in the middle of the road, and would in any case be too heavy for one man to deal with. The most he could take would be a W/T set and a Colt .32 pistol with sufficient ammunition. In the light of what subsequently happened, with Seth finding himself having to deal with four containers, this seems like a sensible evaluation.

Seth then goes on to re-examine his original plan:

The general principle … was to hold up as many enemy troops as possible so that they could not be diverted to other fronts and to slow down the enemy industrial war machine [underlined and queried in pencil] in the country. This work was to be carried out by:

Rousing the national instincts of the people so that the enemy would [be] doubtful as to the wisdom of weakening the occupying forces. This was to be done:

by passive resistance

by minor acts of sabotage

Attacks on rail communication.

Attacks on aircraft.

Attacks on the shale-oil producing plants.

His conclusions now are that he should concentrate on underground propaganda for the first two to three months. If after that time he gauged these activities to have been a success, he would go on to organise passive resistance, forming a band of 50 to 100 saboteurs who would carry out a plan for simultaneous scattered attacks on rail communications, enemy aircraft and shale-oil installations, possibly on high-ranking German officials. This would have the element of surprise, since such attacks would flare up and die out, with no more active sabotage unless circumstances warranted it for at least another six months or so. Sporadic and isolated acts of sabotage, on the other hand, would be of no use, both on account of the small size of the country and the meagre results achieved by such acts.