Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Unicorn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

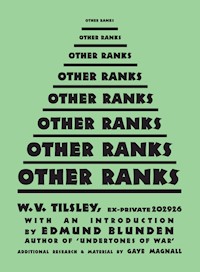

Other Ranks is a First World War classic, first published in 1931 but quickly lost in the wave of war memoirs and novels. It is the fictionalised account of William Tilsley's war experiences through the eyes of ordinary soldier Dick Bradshaw in the 55th West Lancashire Division. This authentic memoir of life and death on the front line begins with Bradshaw's "C" Company leaving the depot at Etaples and heading for their first engagement at the front on the Somme in the Autumn of 1916. Over the next fourteen months it follows the chores behind the line and unwelcome stints on the front line through to his wounding during the Third battle of Ypres in 1917 and subsequent return to Blighty. As well as criticism of the conduct of the war, there is description of the desolation of the landscape and continual conditions of the trenches as experienced by the Poor Bloody Infantry (PBI); wet, cold, frost bite, trench foot, shelling and general life in trenches with continual risk of collapse. War is not a chivalrous experience and his narrative does not hold back in his thoughts and feelings concerning soldiers behind the lines out of the reach of the guns and those at the top. This new edition follows research by Gaye Magnall and is accompanied by introductions from relatives of the three main characters, O'Neill, Magnall and WVT's great nephew, David Tilsley.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 370

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

OTHER RANKS

W. V. TILSLEY

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY EDMUND BLUNDEN

To ERNEST MAGNALLwho livedand CHARLES O’NEILLwho died:

Other Ranks in this book

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For their military knowledge I would like to give thanks to Jane Davies (Curator) and her team at the Lancashire Infantry Museum, Preston; the Great War historian Jonathan D’Hooghe; the military historian Paul McCormick (www.loyalregiment.com); and Ian Verrinder, author of Tank Action in the Great War. And special thanks to my editor, Emily Lane, for her unwavering help and support.

OTHER RANKS

INTRODUCTION

‘THE strength of the raiding party will be 2 Officers and 30 Other Ranks.’ The ancient operation order was lying on my table – had the raid been finally enforced, it would probably not have been – at the time when Mr. Tilsley’s book was brought to me, so that I might have the privilege of an early perusal. I was trying to pierce the obscuration of fourteen years, and to shape again the figures and the characteristics, the business and the condition, of the 30 Other Ranks. The other officer named, for many reasons, was at once clear and animated in my memory; I heard him dryly commenting, as he looked up from lacing his tall boots, on the paper warfare which accompanied all our enterprise. As I scanned the list of the other raiders – the bombing and blocking parties, the mopping-up party, liaison party, and covering parties, I found that many names had gone from my mind, and not many faces looked out from the shadow of the sanded steel hats. It was not all the fault of time and the blessings of peace. The Battle of the Somme had beaten the life out of our battalion; reinforcements had come and many of them had gone; we had been almost hourly changing, and I had scarcely set eyes on a large number of the men now about to be under my direction.

What their daily and nightly experience was, and against what background, it was easier to revive, although in general terms. I saw them as Fate’s prisoners, under a winter sky, sometimes darkly twining more wire on the eastern extremity of our snow-grey prison yard, sometimes moving westward – a few hundred paces – along the concealing wall of clay and metal, with burdens that sometimes moaned. I saw them in erratic processions, desperately ‘keeping touch’ as they met with puzzles of the trench system and traffic, or new obstacles where shells had turned the ditches into clammy mounds; and I saw them in isolated groups, eyeing the opposite parapet, nodding in anxious short sleep, dishing out the tea and cheese and bacon, and waiting for the retaliation which would fall on them in return for our gunners’ work on the German sentry-groups. Then there they were in the town behind the line, marching to the baths in some brewery, organising little estaminet suppers, laying out rows of kit for inspection in their loft, and on parade with every button and buckle and badge polished as though, after all, that art gave as rich a satisfaction as any in the world. I was only at the beginning of my thought of these men. Had I pursued it, I knew that I could never completely reconstruct their war. Between the ordinary infantry officer and them there were wonderful bonds; bombardment, mud, attack, sleeplessness, exposure, over-strain, fear, humour, home, affected all in the prison of the front line; we often shared the same mug of tea, and the same smother of clods and cordite. Intense friendships were formed that defeated the barriers of military rank.

But tradition, routine, and management, together with the impossibility of being in more than one place at one time, did prevent the Officers from being entirely in the intimacies of the Other Ranks; each type, indeed, respected the other’s right to a world of its own; and that is why, from the first, Mr. Tilsley’s account, with all its openness and its circumstantial nicety, was a great discovery. For me, in particular, it had also the fascination, which I have almost given up trying to analyse, of showing me a period and a number of places and episodes which I had passed through; Mr. Tilsley’s Potijze is the sub-sector in which the raiding party mentioned above was intended to ‘capture prisoners, secure identifications, and kill as many of the enemy as possible’. Probably I saw Bradshaw, and he saw me, when my Division was relieving his; I remember the agonising wet cold in which I first followed his battalion doctor round those dejected breastworks, behind which the lively expressions of some of his Other Ranks seemed as actual light and heat in the livid dusk. When Mr. Tilsley says Haymarket, I know which Haymarket he means; indeed, I have never quite recognised the other one. All this is personal, but war-books are largely so. I have met innumerable strangers with whom the of a name like Harley Street – not everybody’s Harley Street! – or Kemmel was a sudden means of hearty and natural conversation. It may be that the recollections aroused are wholly terrible in themselves; but the names, now meaningless to the majority, are talismans of mutual approach to those who have moved on from Cuinchy and Dickebusch to Oldham and Market Deeping.

There must be, in Mr. Tilsley’s resourceful and beautiful narrative, a number of terms of several kinds which, to the survivors, are everything, and to the rest are little or nothing. The title itself, which in its use during the war obtained such a complexity of significance, cannot now be instantaneous in its effect on a new generation, any more than the sight of a solid street reveals the Ypres of this book to the tourist. The map of Flanders in its war arrangement, which underlies all narratives of this kind, is no longer familiar to the public. In a way, Mr. Tilsley’s war will be less bewildering in its topography than others, for, once his characters had been moved north to the salient, they (like my own Division) had the bad luck to stay there, month after month, as if for ever. Whatever these technical difficulties may be, they are in sum no important disadvantage; the humanity of the work presses on, the nervous exaltation and the tragic action are such as to bear the reader over all the momentary intrusions of a forgotten terminology.

It would be a bold man who could assure himself that even the most poignant statements of the nature of the war 1914–1918 have the power of restraining the race from future confusion of the same sort, and perhaps deadlier. If Regan and Goneril had been persuaded to borrow from their libraries the latest work on the atrocious behaviour of an earlier Regan and Goneril to the King their father, would they have refrained from proceeding with their own intrigues against Lear? Were I of the new generation, should I have the imaginative sympathy to turn away from present delights and perplexities and to bind my thoughts to the monotonous emplacements of an obviously absurd and long-finished war? Should I connect the past with the future so curiously as to suppose that by knowing the past I might have some influence on the future? Probably not. Yet it is to be wished, and remembered in our prayers, that the new generation shall have time and matter for clear reflection before the next challenge arises, before the spirit of adventure and ambition of ‘glorious life’ are again made to serve a cause which ought not to have their help.

I should call Mr. Tilsley’s book one of the most valuable warnings that have been written; in the first place, it is written with natural strength and decision, and its words and their movements convey, almost physically, an eager picture of the strange multitudinous original. Then it has the voice of the men (some hardly more than youths) who truly bore the burden of the war, the sort of men who on March 21st, 1918, especially were the loneliest of their race, and were destroyed in their places on the parapet. They were the ‘willing horses’, like and more numerous than the tired but unconquerable subalterns in Mr. Sherriff’s play; their experiences were extreme, and the few of them whose excellence did not lead to their extinction are rarely ready writers. Mr. Tilsley is of the few, and has written in a masterly style a specimen of their terribly multiplied experiences. His reader has not to wait long for a record of what they encountered in the Battle of the Somme on a September afternoon. ‘Where was everybody?’ There were degrees of misery in the prison, and these men accepted the worst. What was the worst? They never seemed to touch bottom; for some passed with scarcely a break from the Somme of 1916 to the Passchendaele battle of 1917; from that to the storms of 1918. The newspapers reported that ‘Sliding is Tommy’s Chief Recreation on the Western Front’ when these men were being blown out of frozen shell-holes by torrents of shattering flame.

Weariness was their principal protest, if it can be called such; and in this I feel the fidelity of Mr. Tilsley’s retrospect. He does not advance arguments in frenzying effects. His scenes (he missed nothing) are completed without an eye to his own personality. The ground is incidentally reported in its hideousness; its immediate interest is that it is to be crossed by the battalion, and it will only be crossed by superhuman exertions and resolution. The forces of death, even, seem subordinated to this tired but onward soldiering; Bradshaw, doing what is demanded of him, scrutinises the latest sacrificial arena coolly. The colours of gun-flashes impress him as the sign of a barrage of unprecedented concentration – and very extravagant. A huge shell dropping just behind him only makes him think of the Arabian Nights. When he is hit, he accepts the opportunity as the only one which could relieve him from the line moving on to the concrete forts; but he finds his way out of the battle with the method of one who has learned all that can be learned of the ways of the artillery, and even as he passes through he criticises a roaring area bombardment as expensive and wasteful. Such were the men who usually remained as Other Ranks until death or wounds transferred them, the closest witnesses of war, the men we trusted to be the same in the next attack as they had been in the last, and to go on leave once to our own three times. They have a candid historian and a survivor in Mr. Tilsley.

EDMUND BLUNDEN

None of the characters in this chronicle is fictitious.

OTHER RANKS

NOT until he saw those seven peculiar-looking kite balloons, steel-grey and still against the evening sky, did Dick Bradshaw realise he was actually near the front. Even then, with those sentinels marking the line of the trenches, he believed some power would impose itself, single him out, expose his deficiencies, and send him back on some duty where he might help only from behind. All the way from Étaples he had been expecting an inspection, when some great general would stand before him and say: ‘Fight for England – you? Run away, boy, and come back when you’re a man!’

But his draft, and another from an East Lancashire battalion –all of them Derby men – had reinforced a depleted West Lancashire battalion without any such interruption. Now he tried to analyse his feelings, for the hundredth time, towards fighting.

He walked thoughtfully along the river-bank – the Somme, he supposed – towards those balloons, on his way to a B.E.F. canteen. The centre one appeared much higher than the three on either side, and, as he looked, a number of small dark puffs sprang around it, like bees about a hive. He walked up quickly behind a group of soldiers whose divisional mark – a square red patch under the collar – proclaimed them as old stagers. He learnt that the bees were German anti-aircraft shells, aimed at some British aeroplane in the same line of vision as the sausage balloon.

In the canteen, he shyly bought several bars of chocolate, then moved quickly away from the sophisticated groups at the counter towards the door, where he met Driver, of their draft. Driver was round-eyed. He motioned Bradshaw outside and cocked up his brow, ears intent.

‘Hear anything?’

From where the balloons were came a rippling vibration, with louder sounds like a distant shaking of blankets. Neither of them could believe that each of the separate explosions making up that quivering of the air was the discharge of a gun. Driver entered the canteen, reappearing in a short time with a steel shaving-mirror. Bradshaw wondered whether he had purchased it for the same reason that he himself had done so at Étaples – to push in his breast pocket because everybody said they were bullet-proof.

Back at the billets a sergeant was calling from house to house: ‘Fall in, the new draft!’ and they arrived barely in time to line up in the roadway before a pale, moustached, irritable sergeant-major jostled them into position with repeated warnings to ‘Get fell in!’

He marched them to an adjacent piece of ground, and presently a lieutenant with a clipped sandy moustache appeared, motioned them to squat on the grass and smoke, and delivered himself of a short homily. He was Mr. Armstrong, temporarily in command of the company.

‘You fellows have come to a good battalion, and a good company. You have a good C.O., good officers, and good N.C.O.s. If you make as good soldiers as the men you join, you’ll do nicely.’

He tapped a neatly puttee’d leg with a yellow cane, and Bradshaw wondered why he continually looked down at it. Suddenly he looked up, staring amongst them with fixed gaze.

‘It’s a bloody business, this war is, as you chaps will discover before long. Old Fritz isn’t cracking up, as you might have heard. He’s fighting tooth and nail, and all the ground we take is dearly paid for. We are winning all right, but there’s a lot to be done first – the Boche isn’t beaten yet. The division you have joined attacked at Guillemont on August the 8th – luckily I was on the B Team and so missed it – but we hadn’t much success. The artillery failed to destroy the Boche wire, which didn’t matter a great deal at first because there was a heavy mist that morning. But the mist lifted too soon, and the Boche machine-guns got busy. In the confusion that followed, an unauthorised order was passed along to retreat, so we had over two hundred casualties without gaining anything. I am ordered to tell you that under no circumstances whatever must there be a repetition of that unordered retreat. The word retreat must be cut out entirely. Two companies of one of our sister battalions managed to get into Guillemont village, but were sacrificed because of lack of support, largely as a result of that order. The village is still in enemy hands.’

Still rapping his leg, he concluded with a few words on the discipline of the 55th Division – the ‘Cast Iron Division’, it was known as – and Bradshaw came away wondering at the officer’s seeming pessimism. It recalled the atmosphere of Étaples, where base details gloated over the human toll taken by the Battle of the Somme. Only twenty-one of the Koylies came back yesterday, they would tell the timid Derby men; or, the King’s Own lost three hundred in two days. Yet the wounded in Camier and Étaples spoke confidently of Jerry being back practically on open ground, so it might be over by Christmas after all.

Anyway, for the first time Bradshaw had heard a first-hand opinion that carried more conviction even than the colonel’s quiet welcome earlier in the afternoon.

THE horizon had assumed a burnished coppery yellowness before they turned in at the billet, but the murmuring had ceased. From grumbling at there being no pay, the old hands had taken to ragging each other for the benefit of the newcomers, who, glad there was no display of acrimony because they were Derby men, grinned their appreciation. One man, whom the others referred to as ‘Legs Eleven’ because his legs were so thin, grinned across at Driver and asked:

‘Arter lousy yet, chum?’

Driver looked horrified.

‘No!’

‘Well, tha soon will be.’

Bradshaw also looked startled. Surely there was no need to get lousy if you took a little care? He looked across at the sprawling figures, features indistinct in the low yellow candlelight. Two of them had tunics over their knees, poring over the seams and neck. Every few seconds there was an audible ‘Tchk’ as thumb-nails met, followed occasionally by a grunt of satisfaction.

‘That was a big bee!’

Another, and obviously a favourite of the rest, was a boy they all called ‘Chick’, extremely youthful and precocious. He came from Preston, and was proud of it. Pausing in the act of pushing his feet into the sleeves of his tunic – there were no blankets – he looked across at the equally boyish Bradshaw and asked:

‘Wheer’s ta coom fra’?’

Bradshaw still resented the fact that he had done all his training with the Manchesters and then had been parted from his friends when being drafted to the Lancashires. He said shortly:

‘Manchester.’

Chick grimaced, and winked noticeably at Legs Eleven.

‘Manchester? Pooh, that’s the spot wi’ two teams at the bottom of the First Division, howdin’ aw’ t’others up!’

The others laughed. They knew that Manchester City and Manchester United had been in low water; that Preston had been going great guns, and had a championship team. Bradshaw grinned with the others, then asked quietly.

‘Where do you come from?’

Chick had wanted this moment, and, bucked with the prowess of his team, replied:

‘A coom fra’ Preston, chum. Proud Preston!’

Bradshaw hesitated a few seconds; cocked his left eyebrow and rubbed his chin, as if pondering.

‘Preston? Ummmmm – Preston? Let me see – they have a football team, haven’t they?’

Chick nearly exploded. For a moment Bradshaw expected trouble, but Robinson burst out laughing again and soon they were all joining in, even the discomfited Chick. The atmosphere cleared.

Bradshaw settled himself for kip between Driver and Anderton, eyeing doubtfully the thin layer of dirty straw that littered the floor. Before he turned over to sleep he reviewed the happenings of the last two days.

No need now to take pains to hide surprise at the things you saw or heard. You could feel amazed at the incredibility of it all without exciting comment. Here he was, lying peacefully, whilst the great battle tossed and turned so near. He laughed to himself as he thought of preconceived notions of what to-day was to bring. When they left Étaples yesterday morning the battle seemed imminent. A few hours’ grace perhaps, and he had expected being caught up in a whirlwind of yelling, hacking, hair-raising confusion; a ceaseless battle that encompassed the whole line and would end only with death or exhaustion. And always he had tried to imagine what would happen when he met one of those big Germans in a hand-to-hand encounter.

Well, they had reached farther up the line than many a thousand volunteers who had been in France a year and more. Everything calm, if uncomfortable, and the others talking as though they expected going on rest! It wasn’t quite the thing to ask questions about such moves at this juncture, but surely the others wouldn’t jump on Robinson so (for suggesting that the new draft meant a return to the trenches) if they hadn’t all been taking a rest for granted? Funny that he knew as little about Driver and Anderton as these Lancashire lads. Rotten that he, Platt, and Wilson should have been parted and sent to three different units after being so long together at Codford and Witley; and all three afraid to approach that big bull-necked sergeant-major to see if he could arrange for them to go up together. Were all drafts split up indiscriminately now, all nominal rolls so strictly adhered to? Well, it was perhaps better that they should have been split up; couldn’t expect a trio to remain long unbroken out here … the other two might be in action now.

He marvelled at the calm acceptance of the war by these Lancashire men. No fuss or flurry; nothing at all to suggest they had been in action. You’d to question them directly about the battle to get any information at all; even then you weren’t sure whether they were joking. And the way they referred to the Germans – almost affectionately. Old Fritz, or Old Jerry! Might be an ally!

He drew comfort from the knowledge that the new draft wasn’t to be hurried at once into action. That proved some sort of order; the situation was in hand.

He looked up at the low roof. Somebody blew out a candle. Strange he should come to France on August the 4th, exactly two years after the war commenced. In 1914 – and early 1915 – his mother had repeatedly told him how thankful she felt that the war would be over long before he was old enough to join. All the time he was in that remote warehouse, going to bed at night thinking what a superhuman being he could become by acquiring some of the strength that was being wasted every day in France, these men had been here in the trenches!

Yet the awe he felt when listening to them was tempered with a certain disappointment. British they might be, but none of them spoke enthusiastically of their battles; he had detected definite relief in their appreciative acceptance of the coming rest. Comforting to know there was still a respite. Might enable one to get the hang of things first.

The last candle went out. A whispering reached his ears from opposite.

‘I don’t like the look of things, anyway, Jem. Don’t be surprised if we go up again in the morning instead of down.’

‘Well, they’ll come in handy for fatigues.’

‘Aye, but it’ll be four to a loaf again to-morrow.’ He turned on his side; sniffed at the musty straw. A funny day it had been. Scuffling with fellows to get a place at the open door of a cattle truck so you could sit comfortably and dangle your legs. Buying canned fruit so you could use the tin as a receptacle for char. (Perhaps they’d issue mess tins to-morrow?) Being separated from your friends without warning and feeling a vague distrust for new acquaintances. (Ten to one they’d borrow things.)

Anyway, they were clear of Étaples and that sand. What a place! Tents and marquees, wired-in I.B.D.s; Y.M.C.A. huts and canteens, with men leaning on them all round, or sprawling in the sand. Fancy the Jocks not wearing anything under their kilts!

He wakened with a start. A pale blue-green haze hovered round the doorless entrance to the little billet. Somebody cursed, then a silhouette outlined itself in the doorway, stood for a few moments, and returned. About four o’clock, thought Bradshaw. How quiet and chilly. A match spluttered opposite, flamed, and went out. A cigarette glowed. He made no sign. He disliked men who rose in the night to indulge in insanitary practices.

A faint tremor quivered on the air. Over the top; whilst he, untried and unblooded, lay scatheless, with the prospect of further unlooked-for freedom before him. He tried to imagine the attack, but after the snippets of conversation he had picked up he knew that all his notions were far from reality. If these people were to be believed, hand-to-hand encounters were rare. You didn’t run or charge across No Man’s Land, but simply walked. Also, you saved your breath, and went silently! No attempt made to intimidate the enemy with blood-curdling yells as at Witley Camp; you offered yourself as a target. If you came out all right, you grinned, and agreed that Old Fritz had put up a good show. If you got a Blighty wound – très bon!

You had to learn not to talk shop, either. Only the boy called Chick had volunteered any information, and he could be excused, being so young. All the same, Bradshaw doubted some of the things he said. Piled on! What was it he’d said when Bradshaw asked him if they still kicked footballs across like they did at Loos?

‘That’s all my eye and Peggy Martin. No Man’s Land is tough going – all oop and down wi’ t’shell ’oils and tangled wi’ barbed wire and things. They blow a whistle to let ’em know we’re coming, too. Tha’s no time for lakin’ at football when tha’s goin’ ower – tha’art fagged too quick. They on’y feed us like rabbits. We’d a’ give Fritz hell at Guillemont but th’artillery hadn’t cut t’wire proper … and later it got so hot that watter-bottles was soon empty. Men were drinking their own afoort’ day were ower. Wettin’ their lips, onnyway. And take a tip from me. Next time we go ower, fasten thi’ trenchin’-tool heead in front so it covers thi’ privates. Jimmy Blount got a short burst there – near on twenty bullets …’

The guns again. Their first faint mutterings had disappointed him in much the same way as did his first view of the Forth Bridge. He expected something mightier. But as he listened, lying, their power grew on him; almost dismayed him. Only stout hearts could stick that out.

Sergeant Whiteside burst in on them first thing next morning. A strong-jawed, fresh-faced man of twenty-five with the reddest hair Bradshaw had ever seen. He bubbled over with good spirits; spreadeagled Robinson and Armour, a deft movement hidden under a cloud of khaki and straw-dust; threw a bundled greatcoat at Chick; all the time roaring gleefully:

‘Show a leg, you lazy bees. D’you know we’re going down the line? Up, you stinkers! What d’you think you’re on? Abbeville, me lads. Abbeville, hundreds of miles out of this, and a pay parade to-morrow. Vin blong and egg and chips till you bust. Get out of it, you nobbuts!’

Whilst the rudely-wakened rubbed sleep and straw from their eyes, he turned to the newcomers.

‘Lucky sods, getting this far and then going back. After breakfast parade get packed up, and leave the place tidy. See these lazy bees do their share of straightening up, too. Chick, you ––––, going off again! Out of it!’

Breakfast was haphazard and rather dismal without mess-tins, but several were passed across and they all mucked in. Bradshaw had left most of his fastidiousness on the filthy tables of the Étaples dining-huts, so drank from a stranger’s mess-tin without recoiling.

But no orders to fall in came. Instead there was a rifle inspection, and doubt entered exuberant minds. Would they go up after all? In the afternoon the old hands had a pay, and everything connected with war was forgotten. Four men left the artillery canteen hopelessly drunk, and at midnight a disturbed reveller – Legs Eleven again – tripped over somebody’s feet and fell heavily across Bradshaw, who squatted with his knees up whilst the belching man laid everything before him. The smell of beer and vomit nauseated Bradshaw; he didn’t go to sleep again. Next morning Legs Eleven wakened unaware how he had managed to get back to billet. Robinson pointed to Bradshaw’s greatcoat.

‘Look at that! All covered wi’ nast. Make him clean it, chum. Great clumsy ha’porth.’

THEY went out, the three new men, next evening, again along the river-bank. Everything around looked worn and tired, as if a peaceful countryside, resenting this intrusion, were withholding its beauty. At nine o’clock they returned to a farmhouse, where a cinematograph picture of the Somme Battle was being shown in the yard on a white sheet hanging down one side of a barn. Men crowded the yard on either side under the deepening sky, and Bradshaw saw little propaganda in the picture. It shocked him. Thin lines of strung-out infantry, yards between each man, crouching forward in the haze-laden air. Were those the waves of advancing infantry he heard of? Several attackers toppled over backwards into the trench. One lay athwart the parados like a dirty bolster – too white and natural to be faked. The most unreal and outrageous attack that could be imagined, yet the picture bore an official stamp. Enough to completely dam any flow of recruits, if shown at home.

The little daylight left scarce sufficed to show them the way back. Méricourt, village though it might be, became a maze. They walked timidly into three billets before they found their own, and Bradshaw, fully expecting to hear a violent denunciation of the film, hardly heard it mentioned. A trifling argument over whether the white-faced corpse lying across the parados was genuine or not, that was all.

Candles, spilling themselves on tin-helmet crowns, added some warmth to the dingy room. A set of hanging equipment cast a fantastic shadow on the dirty wall, and pools of darkness linked the recumbent figures. Chick again searched for lice inside his trousers, running a light along the seams. A smell of scorched khaki hung around as he hunted.

‘Breadcrumbs wi’ legs on’, he called them, and claimed to house the biggest, squashiest specimens in the battalion, any colour.

‘’Ast a getten a diary, theer, chum?’ he asked across the floor to Bradshaw, occupied in making notes. ‘Tha’ll be for it if they find out. Ah! got thee, tha’ fat bee. Tchk! Hear him splash!’

Bradshaw felt already that in Driver he would find a companion more suited to his taste than in the other lads, either Lancashire or Manchester. He had a natural fastidiousness that shrank from many little habits and tendencies so common in the others: yet laughed at them rather than condemned them. He knew himself to be superior in education, speech, and upbringing, but looked upon these doubtful assets as things to hide and keep back from the others whenever possible. He wasn’t going to refuse drinking from somebody’s dirty mess-tin if such an act would foster the impression that he was priggish. He wanted to be one of them.

The others, however, were far too interested in the coming rest to bother about a very ordinary boy of nineteen who had only just come out. The prospect of a few drinks was far more alluring than any number of aspirates.

Driver spoke the King’s English, and besides a nice mind had nice manners. Both he and Bradshaw recognised very clearly what poor belongings these were to bring to a war. Nothing but the power of making oneself invisible or indestructible was of any value. But Driver also had other virtues. He neither drank nor smoked, and there weren’t many companies in France that boasted two non-smokers and non-drinkers. That was the trouble with Anderton. Always a fag in his mouth, and always game for a drink. Weakness of will-power, Bradshaw called it chidingly; not without the suggestion of a sneer.

Having found in Driver such an equable companion, it was natural that a mutual understanding sprang up between them. They kipped together and ate together, one drawing rations for both when the other happened to be absent. Though there was six inches difference in their heights, they contrived always to get next to each other on parade, and found some comfort in doing so. Both felt that the others were too free and easy in their ways, airily borrowing tackle that didn’t belong to them and assuming that no remonstrance would be forthcoming from the owner.

Neither mentioned that the suspicions each began to entertain at Étaples – that the war wasn’t going as well as it might have done – had received some confirmation during their short stay near the scenes of operation; both hoped they would deport themselves with the same degree of optimism, or resigned acceptance, shown by the old hands under conditions that were, to say the least, unfavourable (and, as far as the actual fighting was concerned, distinctly hazy).

In a simple way, Bradshaw had tried to jot down his impressions in a small diary, in staccato fashion. He wondered idly what use it would be keeping a record that might at any time come to an abrupt end, but each day brought some fresh incident that either shocked, surprised, or intrigued him, and, incredible as they seemed to him at the time, he meant to chronicle them. He was collecting quite a store of these surprises, but would anybody believe in their authenticity afterwards?

Those children at Boulogne who canvassed their sisters’ bodies … The men who, too lazy to get up properly at night, used their boots and claimed that it softened the leather ….

He turned to Driver.

‘Coming for a stroll? You, Anderton?’

They went out into the darkened streets, under a solemn sky, low and heavy. Without being aware of it, they approached the cage of German prisoners. They stared curiously but kept walking.

‘I’ll never be taken prisoner, if that’s what it means’, said Anderton emphatically.

Bradshaw looked with some fear at the dark, silent figures hovering against the barbed wire. These were the type they were matched against. Had he smoked he would have flung all the cigarettes he possessed over that wire barrier. Half starved, bearded, miserable-looking lot. He couldn’t imagine meeting one like them in No Man’s Land without feeling hollow. You’d get no quarter from fellows like those, unhappy as they now appeared. Good job that wire was pretty hefty.

‘I’d rather be taken prisoner than lose a limb’, ventured Driver. ‘Rotten to lose your right arm.’

‘Some of the old hands don’t seem to worry about an arm or a leg’, put in Bradshaw. ‘Getting blinded’s worst of all’, he added.

They met Brettle and Bates, two aggressive-voiced older men whom the sorting out at Étaples had thrown together. They had travelled up in the same compartment as Bradshaw, who had been forced to listen to a eulogy of Brettle’s wife and a summary of that man’s intentions when they charged the Germans. ‘I’ll be among ’em red hot’ (only he didn’t say red