Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Open Borders Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

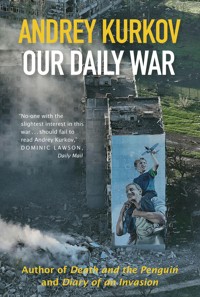

Andrey Kurkov's urgent, humane and unforgettable war diaries continue in a poignant, personal account of life under siege in Ukraine – rich with humanity, dark humour, and unforgettable glimpses of resilience amidst devastation. `A vivid, moving and sometimes funny account of the reality of life during Russia's invasion´ Marc Bennetts, The Times `Uplifting and utterly defiant´ Matt Nixson, Daily Express `No one with the slightest interest in this war, or the nation on which it is being waged, should fail to read Andrey Kurkov´ Dominic Lawson, Daily Mail ____ Andrey Kurkov's war diaries continue: A profound and deeply personal chronicle of life under siege. In this second volume of his acclaimed war diaries, Ukraine's greatest living writer bears witness to a nation enduring the unendurable. From his home in Kyiv, Kurkov captures the surreal and the life-shattering: children learning algebra in metro stations turned bomb shelters, holidaymakers sunbathing on mined beaches, and farmers sowing fields shadowed by missile strikes. On its eastern borders, Ukrainian citizens are put into "filtration camps", en route to Russia … or to execution. To the north, Belarusian forces press refugees into service as mine detectors. This is a lived account – rich with startling vignettes, dark humour and devastating detail – of a country adapting, resisting, surviving. A child downloads movies to a smartphone to watch during nightly power cuts. An elderly Japanese man feeds the hungry in Kharkiv. A soldier carefully rehomes a swarm of bees. A winemaker uses scrap wooden shell crates to package gift sets. A Ukrainian gunner inscribes messages on shells and rockets aimed for Russia: "For Bakhmut", he writes. The family of a journalist killed in the Donbas sells their home to open a bookshop in his memory. Our Daily War is Kurkov at his most intimate and insightful: a record of resilience, heartbreak and fierce national pride. Urgent, humane, unforgettable, this is history as it happens, and as only Kurkov can write it. _____ PRAISE FOR ANDREY KURKOV's WAR DIARIES `Clever, passionate´ Roger Boyes, The Times `Thoughtfulness nearly always prevails over anger; the pieces are flawlessly structured; the tone is devoid of self-pity´ Robin Ashenden, Spectator `Andrey Kurkov [is] one of the most articulate ambassadors to the West for the situation in his homeland´ Sam Leith, Spectator `Immediate and important. . . An insider's account of how an ordinary life became extraordinary. It is also about survival, hope and humanity´ Helen Davies, Sunday Times `Packed with surprising details about the human effects of the Russian assault … genial but also impassioned´ Blake Morrison, Guardian `A thoughtful and humane memoir by one of Ukraine's most prominent living authors´ Simon Caterson, Sydney Morning Herald `Here are the kind of stories you don't see on the television news´ Rachel Cooke, Observer `Kurkov, an internationally-lauded novelist, is strongest when he writes on cultural matters. And this, he demonstrates convincingly, is a cultural war´ Ed O'Loughlin, Irish Times `This book makes for essential reading´ Claire Allfree, Metro

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 533

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

Andrey Kurkov

OUR DAILY WAR

For the soldiers of the Ukrainian army

CONTENTS

8

9

01.08.2022

Do You Know Your Bedroom’s G.P.S. Coordinates? They do!

When, many years ago, I first read that the Internet was invented for military purposes, I did not really believe it. I was a humanities student, and I did not really understand the technological sciences. Only this can explain my naivety. Later I remembered that nuclear bombs appeared much before the first nuclear power plants.

Now that the “military Internet” is playing as crucial a role in Ukraine as the “peaceful Internet”, I no longer have any doubts about the priority of military scientific developments. Moreover, I understand that from a military point of view, everything and everyone in the world is a potential target and that everything in the world has G.P.S. coordinates that enable destructive forces to hit their chosen target with precision. The same G.P.S. coordinates that help me to find a prehistoric cave on the island of Crete can be fed into a missile launched from a Russian submarine in the Black Sea in order to destroy or, in modern Russian terms, to “de-Nazify” this cave.

It seems that at least one of the 40 rockets sent to blow up the Ukrainian city of Mykolaiv on the night of July 31 was programmed to hit the master bedroom of a private house. It was this rocket that killed the owner of the largest Ukrainian 12grain trading company, Nibulon, Oleksiy Vadatursky, and his wife Raisa.

The editor-in-chief of the Russia Today television channel, Margarita Simonyan, immediately commented on this murder, stating that Vadatursky was included in Russia’s sanctions list for allegedly financing “punitive detachments”. It is not clear what kind of “punitive detachments” she was talking about, but Simonyan tweeted confidently: “He can now be crossed off the list.”

I am almost sure that Vadatursky, as the fifteenth richest man in Ukraine according to Forbesmagazine, was helping his country and the Ukrainian army. He must have been confident about Ukraine’s victory. Otherwise, he surely would have left Mykolaiv, subject to daily missile attacks, for somewhere safer. The Le Monde journalist Olivier Truc, who had met Vadatursky a few days before his death, reported that the millionaire was aware that he was a target.

A key figure in the Ukrainian grain export business, Vadatursky was involved in the preparation of shipping routes for the export of grain under the Turkish U.N.-brokered agreement. The first test ship, with 26,000 tons of corn under the flag of Sierra Leone, set sail from the Odesa seaport on Sunday, August 3 without his blessing.

The grain corridor from Odesa through the Bosphorus and beyond has started working and Ukraine has resumed exporting agricultural products during the full-scale war with Russia. It is hard to imagine the cost of insuring the cargo ships, but the fact that export routes have reopened is extremely valuable. Ukraine needs to earn money to support the war effort and will do so mostly in Africa and Asia. Russia can earn money to support its aggression almost anywhere, including in Europe, since it is still selling gas and oil to E.U. countries. 13

In Kyiv, there have been no shortages of gas yet. There were problems with petrol and salt for a few days, but they have already been resolved. The ongoing issue is the constant need for blood donors. Kyiv residents, like other Ukrainians, are already accustomed to donating blood. No-one is surprised by the queues outside the blood donor department at the Central Children’s Hospital, which since the very beginning of the war has been treating wounded servicemen, but eyebrows were raised when, recently, monks from the Kyiv-Pechersk monastery, as well as students of the theological schools and colleges of the Moscow Patriarchate, decided to donate blood for wounded Ukrainian soldiers.

Not so long ago, the leaders of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate refused to stand up to honour the memory of Ukraine’s dead soldiers. Now the monks of the same Moscow-controlled church are donating blood for the Ukrainian wounded. Perhaps they want to prove their loyalty to Kyiv, not Moscow. Or maybe they do so in memory of the monks and nuns of the Svyatogorsk monastery of the Moscow Patriarchate in Donbas, who were killed by Russian artillery shelling. Whatever has brought about this change of heart, the main thing is the result – better-stocked blood banks.

One thing that is now missing in Kyiv are notice boards outside money exchange points and banks announcing the rates on offer. Until recently, the exchange rates had changed very little since the start of the Russian invasion. These exchange rate boards were a reassuring sight around Ukrainian towns and cities. Now, after sharp falls in the value of the hryvnias, the National Bank has forbidden the public display of exchange rates. If you want to know the latest rate you must go into the bank or currency exchange office and, putting on your glasses, peer up at the table of exchange rates behind the glass of the 14cashier’s window. The print size used in these notices is often so small that you might need a magnifying glass to read them. Of course, if they prove friendly and do not mind answering the same question for the hundredth time, the easiest way is to ask the cashier.

Despite tragic news daily, Ukrainians have not lost their sense of humour. Jokes are probably the cheapest way to maintain optimism. The National Bank’s instruction to keep exchange rates in a state of semi-secrecy has spawned dozens, if not hundreds, of anecdotes, jokes, and cartoons. The most popular quip is that in the coming days the Ukrainian authorities will prohibit the display of prices in supermarkets. Shoppers will only know the cost of their purchases once they get to the checkout.

Ukrainians have been greeting other innovations from local or central authorities with humour – albeit sometimes very angry humour. Since last week, many cities have introduced a rule that public transport must stop running whenever an air raid siren sounds and that passengers must be directed to the nearest bomb shelter. This rule has already been introduced in Kyiv and Vinnytsia. True, this has become reality only in part. Buses and trams do stop when the siren sounds and drivers do ask passengers to get off and proceed to a safe place; however, passengers in general remain standing close to the tram or bus – to await the end of the alert and to continue their journey. In this way, moving targets have become stationary ones and easier to hit.

You can argue about the logic of some decisions, but almost all state decisions are motivated now by only two things: security issues and the country’s difficult financial situation. Owing to the lack of money for armaments, the government is 15discussing the introduction of a new ten per cent. tax on all imported goods. That will mean a price hike of ten per cent. on top of the inflation that Ukraine is already experiencing.

In peacetime, a tax like this might stimulate domestic production of goods, but the Ukrainian economy, as President Zelensky said the other day, is in a coma. Many factories and plants have closed, while others are in the process of moving to the relative safety of western Ukraine. For now, increased local production is a distant dream.

It has to be said that some new businesses are appearing – mainly those servicing the war effort – such as producers of clothes and reliable shoes for soldiers and manufacturers of equipment for military personnel, including body armour. These locally produced goods are purchased by volunteers and volunteer groups with money collected from citizens and foreign friends of Ukraine.

War also creates other unusual job opportunities. For example, firms have emerged that provide preparatory surveys for agricultural land that requires demining. The demining itself can only be carried out by certified sappers from private or government agencies. In Ukraine, while only three private companies have the right to clear mines, the licences of two of them are about to expire. These companies employ only between ten and fifteen sappers, while the number of farmers waiting to have their fields and orchards cleared is huge. Some farmers feel they cannot wait and so turn for help to unofficial (and therefore illegal) help. These unofficial sappers are often former military men, as well as treasure hunters who own metal detectors. The unofficial sappers charge a lot of money to do the job quickly but do not give any guarantees.

The official sappers’ charges for demining from a licensed private demining company are quite high, starting from three 16dollars for the inspection of one square metre of land. True, the official sapper companies will sometimes demine private agricultural areas for free. Instead of a charge, they ask the farmers to make a donation towards their petrol costs and the salaries of the sappers. Today, legal sappers in Ukraine earn about $700 per month. How much the unofficial sappers earn is not known. According to stories told by farmers, unofficial sappers ask for $1000 for the survey and demining of one hectare of field (that is, 10,000 square metres).

According to the Association of Sappers of Ukraine, at least 4,800,000 hectares of Ukrainian land are mined, not counting the Chernobyl zone which was also temporarily occupied by the Russian army. Some fields in Donbas have not been demined since 2015.

It is a pity that Google Maps has not yet developed a system to warn you when you are approaching a mined area. According to Google Maps, even today you can reach occupied Donetsk from Kyiv by road in under eleven hours. Are they also trying to entertain us by joking?

08.08.2022

Poetry and Other Forms of Torture

“Posthumous journeys” are once again a sad hallmark of Ukrainian burial culture. The longest and most famous posthumous journey in Ukrainian history was made by the country’s national poet, Taras Shevchenko. He died in St Petersburg in 1861, having returned there after sixteen years of penal service as a soldier in the tsar’s army in the Kazakhstan desert.

Shevchenko was first buried in St Petersburg, but after 17fifty-eight days, the poet’s body was exhumed and, in accordance with his wishes, taken to Kyiv. For two nights, the lead coffin with the poet’s body lay in the Church of the Nativity in the city’s Podil district. It was then loaded onto a boat and taken down the Dnipro River to Kaniv where, on a hill above the riverbank, the poet was once more laid to rest.

The Donetsk poet Vasyl Stus died in a prison camp in 1985, when Gorbachev was already in power in the Soviet Union. In 1989, his remains were transported home by plane to Ukraine from the Urals region of Russia. It is a good thing that he was reburied at the Baikove cemetery in Kyiv and not in Donetsk, the city of his youth, otherwise his grave would by now have been destroyed by Russian special services or the military. A bas-relief memorial to him on the wall of Donetsk University was demolished by separatists in 2014.

The spirit of the nation is kept alive by the souls of dead writers and poets. Just as the Scots’ pride and vision are sustained by the spirit of Robert Burns, Ukrainians still feel supported by the souls of Taras Shevchenko and Vasyl Stus. The first was a victim of the Russian Empire, the second a victim of the Soviet Union. Both lived short lives, both were punished for their free thinking and their poetry, and both died in a foreign land. That foreign land now wants to reach out and disturb their resting places.

Over the past six months, hundreds of vehicles have made the mournful journey from the front line to the homes of fallen soldiers throughout Ukraine. Dead or alive, soldiers must return home.

In Kyiv, a church funeral service was held for Oleksiy Vadatursky and his wife Raisa who were killed by a Russian missile. Their bodies were brought from Mykolaiv for the funeral mass and then taken back to their hometown of Mykolaiv, located 18500 kilometres south of the capital. You might ask why the bodies of a murdered couple had to travel one thousand kilometres for the sake of a church ceremony. The answer is simple – because of the war. Mykolaiv is bombed several times a day and Russian artillery would not allow the deceased couple’s loved ones to say goodbye to them in safety. The posthumous journey of the Vadaturskys allowed their Kyiv friends and State representatives to pay their respects.

After his death, it emerged that Vadatursky had played a key role in preventing the Russian army from occupying the port city of Mykolaiv. At the very beginning of the war, he gave his company’s cargo vessels to the military to block the port’s entrance, making it impossible for Russian ships to approach.

In Mykolaiv, as in other cities near the front line, every morning the authorities report to residents what has been destroyed during the night by shelling and Russian rockets. The city is gradually being reduced to ruins. Many villages around the city have already been completely destroyed. Their inhabitants have either died or have become refugees. At first, of course, the inhabitants of the villages nearest to Mykolaiv sought protection in the city. As in the Middle Ages, people see the city as a fortress that can protect them. The villagers from around Mariupol must have seen that city in the same way, as the inhabitants of the town of Derhachi near Kharkiv still do.

When a town or city, or what is left of it, is captured by the enemy, there begins a procedure for checking and registering residents, one decreed in the Russian army’s rulebook. This is called “filtration”. Filtration camps are set up near the captured cities. Section by section, the local population are told to bring their documents and mobile phones and are then driven to the camp. Only those who have no patriotic tattoos and 19have not made pro-Ukrainian posts on social media networks and who can prove their loyalty to Russia, “pass” the filtration process.

For a while, the Russians denied the existence of filtration camps in the occupied territory of Ukraine. Later, however, they justified their use, saying that the camps help to prevent pro-Ukrainian elements – Maidan participants or army personnel, for example – from entering Russian territory. This explanation indicates another reason why the Russians have set up eighteen filtration centres in former prison camps and purpose-built detention facilities in the occupied territories. Those who pass the filtration process are sent to Russia as refugees. They are mostly sent to depressed regions: to Murmansk in the far north and even Kamchatka, areas where the local population is particularly sparse. Those who do not pass filtration are sent to prison camps or, according to some eyewitness accounts, are killed immediately inside the filtration camps. Almost all of those who are prepared to speak about their experiences during the filtration process prefer to remain anonymous. They are afraid of intimidation.

Among those Ukrainians who have gone through filtration and have been sent to Russia, some have managed to escape to Estonia or Finland and then find their way back to Ukraine, bringing with them accounts of the filtration process. Their stories are similar. A lot has already been written about the checking procedures employed – the interrogations, fingerprinting and compulsory completion of questionnaires. In fact, these procedures were invented in the 1940s by the Soviet secret police agency of the time.

For me, the most surprising thing about the shadowy activity inside the camps is the use of poetry as torture or punishment. Early on it was said that Ukrainian citizens and prisoners of 20war were being forced to learn the Russian anthem, a slightly modified version of the Soviet anthem. But recently, reports tell of Ukrainians being forced to memorise the poem “Forgive Us, Dear Russians”.

I had assumed that this poem had been written by a Russian poet “on behalf” of the Ukrainians, but the poem’s author is a Ukrainian, a pro-Russian poet from Poltava, Irina Samarina. She wrote the poem in 2014 in response to a better-known poem “We Will Never Be Brothers” by the then-Russian-speaking Ukrainian poetess Anastasia Dmitruk. Anastasia’s poem, addressed to the Russians, ends with the words “You have a tsar, we have democracy. We will never be brothers.” Although now for the most part forgotten, in 2014 this poem became quite a popular song. Anastasia Dmitruk continues to write poetry, but mostly now in Ukrainian. She also helps to organise protests around the world against the Russian war in Ukraine.

Irina Samarina grew up in Poltava in central Ukraine, but her work is little known. On her Facebook page, she writes, apparently without irony, that she works for the G.R.U., Russia’s military secret service. She also reposts the anti-Ukrainian video monologues of the pro-Russian propagandist Anatoliy Shariy, who probably does work for the G.R.U. He is suspected of receiving money from the Russian secret services to buy a villa in Spain. Spanish authorities have taken possession of the property.

Samarina’s poem states, “But there is no Ukraine without Russia, just as a lock has no use without a key … But they will not destroy my love for Russia, as long as we are together, God is with us!” Russian mass media and online platforms have tried to boost Samarina’s popularity inside Russia, presenting her as an example of “healthy Ukraine”. This strategy does 21not seem to have worked, possibly because of the mediocrity of her poetry. However, at least one of her poems will remain in the memory of Ukrainians who experienced Russian captivity.

For many Ukrainians trapped in the occupied territories, having to learn rotten poetry will not be their worst memory. Married couples are sometimes separated in the filtration camps: a wife passes filtration and is driven out of the camp and into Russian territory, while what happens to her husband remains unknown.

Many “filtered” Ukrainian citizens who end up in Russia are helped secretly by Russian volunteer groups to travel to Europe. This activity is co-ordinated mainly from abroad, including from Georgia and Britain. The Rubicus group, which has already helped nearly 2000 Ukrainian internees to leave Russia, operates from Britain but with help from Russian volunteers, who are monitored constantly and hunted by the Russian special services.

Russians can denounce any of their compatriots seen trying to help Ukrainian refugees. In the city of Penza, for instance, neighbours reported Irina Gurskaya, a volunteer who was collecting clothes and money for refugees who had been brought from Mariupol to a nearby village. Gurskaya was summoned to the police station and questioned for several hours, being threatened with prosecution and huge fines. When a local lawyer, Igor Zhulimov, volunteered to defend Gurskaya, his neighbours painted the words “Ukrainian Nazi” on his apartment door. Nonetheless, some Russian volunteers continue to collect money for Ukrainians and help them to reach the borders with Estonia or Finland.

The vast majority of Russians support the aggression against Ukraine. For the few people who choose to help Ukrainians, the pressure and persecution can become too much. Then they also 22leave for Europe, further increasing the proportion of people in Russia who support Putin.

Another factor enlarging the pro-Putin majority in Russia is migration from the occupied part of Donbas, from the two separatist republics. These migrants would probably be happy to learn Samarina’s poem “Forgive Us, Dear Russians”, but most likely they have yet to hear of it or of her. They prefer Pushkin, not as a poet, but as a symbol of the greatness of Russian culture. Recently in Ukraine, defenders of Russian culture have been called “Pushkinists”.

The war against Russian culture has become an integral part of the Russian–Ukrainian war. Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture and Information has announced a project called “Turn Russian Books into Wastepaper”. The project plans to use the money raised from recycling Russian and Soviet books to support the Ukrainian army. I asked my Ukrainian publisher Oleksandr Krasovitsky how much money could be made by recycling such wastepaper. “Very little!” he said, “there are almost no factories in Ukraine that can efficiently turn wastepaper into usable paper.” I wonder whether this project to recycle all Russian books will continue even if it is proven to be inefficient.

The war of words goes on.

15.08.2022

War-time Odesa

Last Saturday, “Don Quixote” was performed at the Odesa Opera and Ballet Theatre. Although it started at four o’clock, the hall was almost full. Daytime is now considered safer for theatre. The poster for “Don Quixote” still states that the ballet 23was staged by the Honoured Artist of Russia, Yuri Vasyuchenko. Not so long ago he was the chief choreographer of the Odesa Theatre, but he now works in Kazakhstan, at Almaty’s Abai Theatre. The new chief choreographer is Armenian, Garry Sevoyan, and the guest principal conductor is Hirofumi Yoshida from Japan. Among the ballet dancers and theatre musicians there are many citizens of neighbouring Moldova.

The theatre’s cosmopolitan mix reflects Odesa’s origins: it is a city built by the Basques, Spaniards and French. One of the first mayors of the city was the Duke of Richelieu, whose monument stands at the top of the city’s famous Potemkin Steps, above the city’s presently non-functioning passenger port. Richelieu was both mayor and governor-general of Odesa. When the Bourbons regained the throne in France, he returned home to become Prime Minister in the government of Louis XVIII. It was Richelieu who gave impetus to the development of the port of Odesa, from which now, during the war, flotillas of cargo vessels loaded with wheat, corn and other food products set out to feed the world.

In the last two weeks, Odesa has not been bombed and life, especially the cultural and epicurean, has flourished, almost returning to pre-war levels of activity. Odesa’s most famous market, Privoz, is open. However, the fish rows are practically empty – fishermen are forbidden to go to sea. Odesa without fresh fish is a vivid symbol of wartime life. It was the same during World War II, when Odesa was occupied by Romanian troops, Hitler’s allies. On the other hand, fruit and vegetables are abundant and prices have risen very little.

Tourists, refugees from eastern Ukraine and residents have all already decided exactly where it is (relatively) safe to swim in the sea off Odesa. Officially, there is a ban on going to the beach. Mines hidden under the water have proved fatal – most 24recently near the beach in Zatoka where two people were killed and one wounded. Nonetheless, people still bathe along the length of the coast of Odesa region. Hotels and recreation centres are working. Local winemakers deliver wine to the beachside bars and cafés. Watermelons in the south of Odesa region are as sweet as the better-known Kherson variety. And now they must replace watermelons from Kherson because Russian troops have prohibited Kherson farmers from delivering any products to unoccupied areas of Ukraine.

Despite the holiday atmosphere in Odesa city, the region is regularly reminded of the war. Russian forces know that Odesa’s coastline is protected by American Harpoon missiles. Russian intelligence would like to seek out the launch pads so that they can be destroyed. No-one knows whether Russia has managed to find and destroy even a single missile launcher, but Russian missiles frequently blow up hangars and warehouses along the Odesa coast, apparently believing that they contain the Ukrainian army’s weapon stocks. Zatoka, one of the most popular Ukrainian resorts, was likewise sprayed with rockets that killed several tourists and left hotels and cafés in ruins.

In Odesa region, even internally displaced people become “holidaymakers”, especially those who can pay to stay in campsites and hotels. But autumn will arrive, spelling an end to the holiday season. Once September comes, those “holidaymakers” who remain in the region will be considered internally displaced people. Many of those who now pay to stay in holiday houses will be allowed to continue to stay there for free during the winter. The only problem is heating. Most holiday homes and hotels do not have any because they are, for the most part, used exclusively in the summer season.

In their determination to find out where in Odesa region the 25Ukrainian army is hiding its rocket launchers, Russia’s troops and its main intelligence directorate of the Russian Ministry of Defence are actively scouring the region for potential traitors, especially among Russian citizens who have been living in Ukraine.

It is easy for them to manipulate Russian citizens – they can be blackmailed through relatives who are still in Russia. But there are also a number of pro-Russian Ukrainians. The money offered for such information may also be a factor. If you agree to collaborate, payment is sent directly to your electronic wallet. All you have to do is walk or drive around Odesa and Odesa region photographing everything related to the Ukrainian army, sending the co-ordinates over the Internet.

The Ukrainian security service continuously reminds citizens to be aware of anyone who photographs military or civilian structures and to report them to the security services or the police. All Ukrainians, including me, get reminders about this on their mobile phones.

The Ukrainian counter-intelligence officers are also keeping busy. They are especially interested in Russian citizens living in Ukraine. There are a lot of them: 175,000, according to official statistics. Most of them are on the side of Ukraine in this war, but there are plenty of exceptions. Unlike citizens of Ukraine, a citizen of another country living in Ukraine cannot be tried for treason. He or she can only be tried for aiding the enemy or for espionage. This accusation could still land a person in prison for fifteen years.

Recently, the Prymorsky Court of Odesa sentenced a Russian citizen living in Odesa to 30 months in prison for providing Russian intelligence services with information about the location of Ukrainian military facilities. He was a native of Moscow and had worked previously at the Institute for Nuclear 26Research of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He moved with his Ukrainian wife to live in Odesa.

His short prison sentence angered many Ukrainians. They once more raised questions about corruption in the Ukrainian judicial system. This time, however, corruption does not seem to have played a part in the court’s decision. During the judicial investigation, the Russian citizen sincerely repented of his crime. What is more, while he did not bribe the judge – a not uncommon occurrence in Ukraine – he chose to donate almost $100,000 to the Ukrainian army. I think that this case should be publicised so that those Russian agents who are caught in the future know how to get a minimum prison sentence for their crimes.

My Odesa friend Konstantin, a retired journalist, cannot now see his wife. She has been stuck in Moscow since the beginning of the war. For many years, she lived shuttling between Odesa, her home, and Moscow, where her eldest son settled. She went there last to look after her grandchildren. In Moscow, she received a Russian passport and applied for a pension, although she was born and lived most of her life in Odesa. Before the war, she regularly visited Konstantin. On the last visit she left him her Russian pension bank card as his Ukrainian pension, the equivalent of 160€ a month, was not enough for him to live on. Since the beginning of the war, all Russian bank cards have been blocked in Ukraine and Konstantin no longer has access to this additional money, meaning that he has no money for the medicines he needs for his eye treatment. He is almost blind.

More and more couples find themselves separated because of the Russian passport held by one of them. Russian citizens with temporary Ukrainian residence permits can no longer renew them and are required to leave, as are citizens of Belarus. 27Those who have been living in Ukraine for a long time and have permanent residency can stay, although Ukrainian special services certainly keep an eye on such people.

Recently, they were keeping tabs on the Akivisons, a family of hotel owners in Odesa whose four popular hotels include the Mozart located near the Opera House. I was lucky enough to stay there several times. The Akivisons are all Russian citizens who live in St Petersburg. Lina Akivison, the daughter of the founder of the company, somehow managed to get a Ukrainian passport without coming to Ukraine and, as a citizen of Ukraine, she managed to re-register the hotels in her own name. In April, some investigative journalism led to the opening of a criminal case regarding her illegal acquisition of Ukrainian citizenship. Now the hotels have been transferred to the state committee for the management of confiscated assets. From the very beginning of the new phase of the war, Lina Akivison has publicly supported the actions of the Russian army in Ukraine and advocated the annexation of occupied Ukrainian territories.

We can assume that she will probably not repent of receiving a Ukrainian passport illegally – no doubt in return for a bribe. She is also unlikely to donate money to the Ukrainian army, but at least she will no longer receive income from any hotels in Odesa. According to the law adopted by the Ukrainian Parliament in early March 2022, all assets of Russian legal entities will be confiscated without compensation and the money received from their sale will be transferred to the state.

At the end of February this year, a new private museum of contemporary art was due to open in Odesa. It was supposed to be located on the premises of the recently bankrupt Odesa Champagne Winery, built in Soviet times. The war has pushed back the opening of the museum until calmer times. The contemporary art collection that was supposed to hang on the 28walls of the former factory has now been evacuated to western Ukraine. However, the Odesa Champagne, which this plant produced before its closure, is still on sale in Odesa, Vinnytsia, and Kyiv. This plant produced so much Champagne that there may even be enough of it for the future celebration of Ukraine’s victory and the end of the war.

There is no great demand for Champagne in Ukraine at the moment. It remains, however, a tradition to drink it at theatre performances, which, thank goodness, are taking place again. So, Champagne will be drunk during the intermissions at the Odesa Opera and Ballet Theatre, in the buffet on the second floor, where theatre lovers can also obtain sandwiches filled with red caviar.

Odesa has always tried to live glamorously, and the city does its best to keep this up even during the war. Odesa’s French first governor must have brought to the city a love for luxury and Champagne, and it seems natural even in today’s grimmer context.

Upcoming performances at the Odesa Opera and Ballet Theatre include Rossini’s “The Barber of Seville” and Verdi’s “Aida”, as well as the ballets “Masquerade” by Aram Khachaturian and “Giselle” by Adolphe Charles.

22.08.2022

Air Raid Sirens and Crowd Funding

As evening falls in the forests of Zhytomyr region you can often hear the blows of an axe or the sharp buzz of a chainsaw. After dark, late in the evening and sometimes in the middle of the night, you might catch the hum of old cars pulling trailers full 29of logs, or even the rumble of huge timber trucks carrying the trunks of freshly cut pines away from the forests. The old cars and their trailers are usually making for nearby villages.

The same thing is happening all over Ukraine. This is how the rural population is stocking up on fuel for the winter. This method of obtaining firewood is of course illegal, but the police rarely pay attention to small-time illegal lumberjacks. In the past action was sometimes taken against the large-scale night loggers, those who processed the wood and sold it to builders and furniture makers. These illegal logging operators are now also working for the winter firewood market, but the police have no time to deal with them.

Since 2014 and the beginning of the war with Russia, many residents of Ukrainian villages and towns have ceased to put their trust in gas-powered boilers. They have converted their heating systems to run on other fuel, especially wood. In every village yard and even in the yards of private houses in small towns, the piles of firewood, covered with oilcloth against rain, are steadily growing. I would not be surprised to learn that the same thing is happening in Poland, the Czech Republic, or even in Austria. In Europe, this phenomenon would be due to soaring gas prices. In Ukraine, the prices for gas and gas heating remain at pre-war levels. A decree freezing fuel prices was recently signed by President Zelensky to reassure Ukrainians as winter approaches. Nonetheless, for rural dwellers, the gas bill is the one that hurts the most. While Zelensky can freeze the price of gas, electricity and water, he cannot guarantee the supply of these amenities to Ukrainian homes this winter. That will depend on the Russian artillery. There are already several Ukrainian cities, both occupied and free, which will not have heating this winter.

While Ukraine stubbornly prepares for winter, air raid sirens sound many times a day, warning of Russian missiles flying 30towards military and civilian targets. The explosions kill citizens and destroy buildings and the infrastructure around them – gas, sewerage and water pipes, electrical networks, and thermal power stations. Where possible, repair teams immediately set out and begin repair work, that is, if the town or city has not been destroyed completely.

There will be no heating this year in Mariupol or Melitopol, in Sloviansk or in Soledar. While heating in Kharkiv and Mykolaiv is by no means a certainty.

Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko has warned residents that the temperature in apartments this winter is not to rise above 18°C. He advises people to buy dry spirit for camp cookers, look out warm clothing, and find additional electric heaters. In our apartment in the centre of Kyiv, the temperature never rises above 18°C in winter. Quite often it drops to thirteen. We are already accustomed to the cold.

The other day, the mayor of Kharkiv, Ihor Terekhov, said, “The enemy is killing the heating system, but we will get through the winter.” Repair work on the city’s centralised heating systems goes on around the clock and very often under shelling. For the system to work properly this winter, all 200 kilometres of pipes, both those above ground and underground, will have to be replaced during October. Everything depends on the Russians not destroying the pipes and the thermal power plants that have already been repaired.

Oleksandr Senkevych is the mayor of another regularly shelled city, Mykolaiv. He has warned residents that the city’s most difficult heating season lies ahead. “Shelling is possible. Today it is warm, but if tomorrow the heating infrastructure is shelled, it will be necessary to drain the water from the system, repair damaged pipes, and only then re-launch the system. During this time, you could be freezing,” he said. 31

Senkevych mentioned something else that all residents of large cities are afraid of, something that is not being discussed: the evacuation of residents in the event of the absence of heating. It would be strange if this issue were not broached sooner or later. The deliberate destruction of thermal power plants by Russian missiles during sub-zero temperatures will make any city uninhabitable. Water will freeze in the buildings’ pipes and sooner or later those same pipes will burst. Electric heaters will not suffice to heat an apartment through a Ukrainian winter. But how could a city’s population be evacuated and to where? We are talking about hundreds of thousands of people all requiring simultaneous evacuation – no simple task.

The sirens, which warn Ukrainians about the danger of missile attacks, have recently taken on another function: they have become the signal for flash mobs fundraising in support of the Ukrainian army. This crowdfunding plan was created by Natalia Andrikanich, a young volunteer in Uzhhorod. When she found herself getting angry every time an air raid siren growled over the city, she decided to change her attitude and made the siren a reminder to herself that the Ukrainian army needed support to put an end to the need for sirens once and for all. From then on, every time the siren sounded, as well as making her way to the bomb shelter, she donated a small sum of ten to twenty hryvnias (fifteen to 30 euro cents) to the bank account in support of the army.

Other Ukrainians heard about the idea and started doing the same. Now every siren sounding in Ukraine increases the financial support for the Ukrainian armed forces. Most of the money raised this way comes from regions away from the front line. The well-known Kharkiv photographer, Dmitro Ovsyankin, told me,

“In Kharkiv, nobody’s salary is large enough to allow them to donate that often!” 32

Indeed, there are areas and cities where the sirens never stop. It is like that in Nikopol and Derhachi and the entire area of the Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, Odesa and Mykolaiv regions. In these places, you simply do not have time to go online to donate.

We do not know exactly how the money that goes into the bank account in support of the Ukrainian army is spent. This is definitely a “military secret”, but Ukrainians can monitor how and on what the best-known and most active volunteers spend the money they collect. To date, the most successful volunteer fundraiser is the famous showman, stand-up comedian and popular T.V. presenter Serhiy Prytula.

Until 2019, Prytula was a rival of comedian Volodymyr Zelensky on T.V. comedy shows. When Zelensky became president, Prytula started to take an active interest in politics. He tried unsuccessfully to get into Parliament as a deputy from the Voice party founded by the Ukrainian rock singer Svyatoslav Vakarchuk. Prytula also used the Voice platform to put forward his candidacy in Kyiv’s mayoral election. Now many Ukrainians see him as a rival to Zelensky in the next election. He has proved his popularity in the process of collecting money for the “people’s Bayraktar”. He planned to raise 500m. hryvnias (about thirteen million euros) for three combat drones. In just a few days, he collected 600m. hryvnias and immediately brought the fundraising project to a close.

When the Turkish manufacturer of Bayraktar drones learned about Prytula’s fundraising project, they decided to donate three drones to the Ukrainian army. So Prytula announced that he would spend the money he had raised to buy a Finnish ICEYE satellite – capable of taking high-quality photographs of the earth even in bad weather. In addition to the satellite itself, he paid for an annual subscription to another group of satellites, which can also provide Ukraine with high-quality photographs 33of Russian army positions in Ukraine and Crimea. In short, Prytula’s volunteering and popularity have reached cosmic heights. However, not all volunteers are television celebrities with political ambitions and, for those with more modest positions in Ukrainian society, it is far more difficult to raise money.

The cult poet from Kharkiv, Serhiy Zhadan, has been actively supporting both military funding campaigns and the cultural life of his much-shelled city from the very beginning of the all-out war. Recently, he announced plans to raise money for one hundred used jeeps and pickup trucks for the army. Zhadan has already sent fifteen vehicles to the military. The cult prose writer from Uzhhorod Andriy Lyubka, whom I mentioned a couple of months ago, has already delivered to the front line the 38th vehicle bought with money raised by him.

In Ukraine, they are joking that there are no used jeeps and pickups left in Europe. Soon, they say, vehicles will have to be brought in by ship all the way from Australia. Every joke has an element of truth in it. The number of jeeps and pickups already handed over to the Ukrainian army today runs into the thousands. In some cases, the military immediately installs mortars or mini-artillery systems and sends them into battle. The military regularly posts on social media networks photographs both of newly received vehicles and of vehicles destroyed by Russian artillery and tanks. The latter photos prove the continued need for further second-hand jeeps and pickups and indicates that replacements will be required for as long as the war continues. Ukrainian volunteer fundraisers could remain key customers for sellers of these versatile vehicles from the rest of Europe for a long time to come.

28.08.2022

Traitors and Bees

Last week, volunteers arrived in Kyiv with homeless and orphaned cats from two destroyed cities on the front line in Donbas, Bakhmut and Soledar. The cats and kittens need homes.

While news about the evacuation of pets from the war zone has long ceased to be exotic, the tale of some recently internally displaced bees from the Bakhmut area did catch my attention.

Before the war, there were thousands of beekeepers in Donbas. In addition to coal, the region has always been famous for its honey. Two years ago, despite the loss of Crimea and part of Donbas, Ukraine was still exporting more than 80,000 tons of honey per year. Alas, for the next year or two and perhaps even longer, we can forget about such impressive figures in the honey trade.

We are already accustomed to the idea that pets can become homeless because of the war, but now we have to get used to the idea that tens of thousands of bee colonies have become homeless in Donbas and southern Ukraine. Usually, if a hive is damaged by shelling, the bees become wild and “return” to nature. They swarm from place to place, settling on the walls of destroyed buildings or in trees, until they find a more permanent place for themselves, such as in the hollow of an old tree or the attic of an abandoned house. While looking for a new home, the bees are also trying to fly away from the noise and destruction of war. They flee, not only because collecting pollen that smells like gunpowder is not very pleasant but chiefly because bees love silence, silence in which they can hear each other’s buzzing.

At the beginning of summer, on the front line near the town of Bakhmut, a swarm of bees that had flown away from 35a war-damaged hive settled near some Ukrainian military positions. Among the soldiers was a beekeeper, Oleksandr Afanasyev. He had left his hives at home in Cherkasy region in the care of some volunteer beekeepers. When he saw the swarm, Oleksandr took an empty wooden shell box, made some holes in it and settled the bee colony inside. The bees put up with the cramped conditions of their new home and, having settled inside it, flew off to explore their surroundings in search of flowers.

At the end of the summer, Oleksandr was ordered to transfer to another detachment in a different sector of the front. His brothers-in-arms, who knew nothing about beekeeping, were afraid to take responsibility for the hive and asked Oleksandr to take it with him. Soldiers are not allowed to keep any pets, let alone swarms of bees. So, it was lucky that a volunteer from Cherkasy region, Ihor Ryaposhenko, who brings old pickups and jeeps to the front, arrived at Oleksandr’s detachment in time to take the bees home with him, although he had no experience of beekeeping.

The bees travelled more than 700 kilometres in the ammunition box which had become their new hive. They survived the journey and are now settling in Ihor’s garden. So as not to disturb them further, Ihor decided not to move them to a proper hive and has left them in their makeshift home. Fortunately, there are several beekeepers in the village, so Ihor has someone to advise him on caring for the bees. He will soon borrow a honey extractor from his neighbours to pump out the honey and will send some proportion of it to the frontline position where the bees first found their military home.

The location of these Ukrainian military positions has not changed recently, although Russian troops are approaching Bakhmut from the east and shell the town every night with artillery and rocket launchers. More than 70,000 inhabitants 36lived in the city before the war. There are now about 15,000. The Ukrainian military does not have much confidence in the residents. They have chosen to remain in the town or nearby villages in spite of being offered help to evacuate.

Many of these “remainers” continue to say, “We will wait. Let’s see what will happen next!” Ukrainian soldiers call such people “waiters” because they seem to be waiting for the territory to be captured by Russia. Some of the “waiters” do seem to have a positive attitude towards the Ukrainian soldiers. Sometimes they give them vegetables and fruit. Nonetheless, not all are considered to be completely trustworthy. They could be coming specifically to see where military equipment is located, information they could send to the Russian artillery forces.

Of those who remained in occupied Melitopol and Mariupol, some, including certain former police officers, decided to cooperate with the Russian occupation authorities. The topic of betrayal is not very popular in Ukraine and certainly not very pleasant to discuss. But recently, more and more information has appeared about Ukrainians helping the Russian army and special services in various regions of the country, even in Kyiv. Arrests have been made among officials of the Cabinet of Ministers and the National Chamber of Commerce, leaders of the pro-Russian Opposition Bloc for Life party, prosecutors, and judges. Those arrested have been charged with treason. But these Kremlin agents are far outnumbered by collaborators inside the occupied territories. The first shock for Ukrainians was the number of judges, prosecutors, S.B.U. officers and police officers who switched to serving Russia in Crimea after the annexation in 2014. It was a mass betrayal but, as it turned out, it was also the result of long and painstaking work in Crimea by the Russian secret services.

It was also the result of a failure by Ukrainian special 37services. Now, even in Donbas, betrayal is not as widespread as it was in Crimea. Most of the remaining residents do not want to cooperate with the occupiers. But Russia possesses many tools to force Ukrainians to recognise the occupation administrations, at least passively. You have to register with them to receive humanitarian aid, to have your water supply reconnected, or to access any kind of pension.

The theme of betrayal remains like a scar on the villages and towns around Kyiv that fell under Russian occupation at the beginning of the war. In every village, every town, there were Moscow supporters who offered the invaders lists of pro-Ukrainian activists, the addresses of participants in the Maidan protests and veterans of the anti-terrorist operation in Donbas.

In the village of Andriivka, not far from Borodyanka, north-west of Kyiv, a former monk from a monastery belonging to the Moscow Patriarchate turned out to be a traitor. He not only allowed several of the invaders to stay in his house but also showed them which houses in the village could be burgled and which residents could be kidnapped and exchanged for ransoms. The monk did not have time to escape when the village was liberated. He was arrested, tried and sentenced to ten years in prison. Another family, migrants from Donetsk, who settled in the village after 2014 and who had also helped the Russian occupiers, left with the Russian army as they retreated to Belarus.

More than 30 Andriivka residents are still listed as missing. Russian soldiers shot at least seventeen people and many houses are still in ruins. Mykola Horobets, a well-known Germanist and retired researcher who worked for most of his life at Ukraine’s central academic library in Kyiv, went to his house in Andriivka as soon as the village had been liberated from 38Russian troops. Before the war, he would have spent all summer there, but last week he visited his childhood home for only the fifth time since the village’s liberation.

He has managed to plant potatoes but only in the part of the garden that is closest to the house. He is afraid to work the land further away – what if there are mines? The garden has not been checked for explosives. Despite the reduced size of his potato plot, Mykola is moderately happy with the crop. He has been able to put a good store of potatoes away in his cellar. Now he is stocking up on firewood for the winter. He, too, often thinks of the traitor monk and the traitor resettlers from Donetsk.

During the occupation, Mykola’s hut was lived in by Russian soldiers. They were very surprised by all the German language books on the shelves. The soldiers asked the neighbours about the owner of the hut: is he by any chance a German? They left behind a broken sofa, several issues of the Russian Ministry of Defence newspaper KrasnayaZvezda(Red Star), and many personal belongings, including a hat, powder to make an energy drink, and a camping pot for cooking food.

When Mykola arrived for the first time after the village had been liberated, Ukrainian police entered the house ahead of him. They looked around and asked Mykola to identify what had been left by the Russian soldiers. Mykola found a large canister of machine oil in the shed, probably for the engine of a tank. The police were not interested in oil but one of them took a fancy to the Russian soldier’s camping pot and requisitioned it.

The canister of engine oil is still in the shed. Perhaps the local history museum in Makariv, the nearest town, will take it. The director of the museum is preparing an exhibition about the occupation of the Makariv district and has asked all 39residents to donate artefacts from the Russian aggression to the museum.

“I’m afraid to come to Andriivka too often,” Mykola admitted to me. “In the evening, a lot of people here get drunk and then they let off guns in the dark. The Russians probably left a lot of weapons around too.” It seems that the police are in no hurry to look for “trophy” weapons collected by villagers. And no-one wants to criticise alcoholics who survived the occupation. Some believe that they drink because of the psychological trauma, although this does not make the situation less frightening.

In fact, all residents of Andriivka are now deeply traumatised, including those, like Mykola, who were not there during the occupation. He remained in Kyiv with his adult daughter, who has cerebral palsy. Because of her, he did not even think of trying to evacuate from Kyiv. His village neighbour Andriy, a friend since childhood, is also an alcoholic. Sometimes Andriy steals vegetables from Mykola’s garden and sells them to buy a bottle. Oddly enough, he is also a beekeeper, or rather a former beekeeper who still has bees. One swarm recently “escaped” from Andriy and settled on a cherry tree in Mykola’s garden. Andriy brought a ladder around and climbed up the tree, breaking several branches in the process, although he did manage to recapture the swarm.

I have a feeling those bees will fly much farther away next time, to a place where their drunken owner will not be able to find them.

Neglect is a form of betrayal and bees, like people, cannot forgive a traitor.

06.09.2022

Uman Gets Ready for the Jewish New Year

Every year in September, the population of the town of Uman, in Cherkasy region 190 kilometres south of Kyiv, quadruples as Hasidic Jews arrive to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.

This pilgrimage to Uman honours one of the founding fathers of Hasidism, Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav (Breslov), who is buried there. He died in 1810 in Uman and, in accordance with his wishes, lies in the Jewish cemetery next to the graves of the victims of the Haidamack massacres of 1768. Had Rabbi Nachman not insisted on being buried in Ukraine, his ashes would have been transported to Jerusalem and today Uman would be an ordinary, quiet, provincial town. As it is, the city has long been Ukraine’s main centre of religious pilgrimage and tourism.

A significant industry has developed around the celebration of the Jewish New Year involving transportation, real estate, rental accommodation and kosher cuisine. Many Hasidim have purchased real estate in Uman and are involved in the property rental business themselves. Before the war, dozens of charter flights from Israel and the United States of America flew into Kyiv at this time of year, and lines of specially reserved buses and cars could be seen waiting at the airport to whisk the pilgrims off south to Uman.

The celebration can last for over a month and security has always been an issue. In cooperation with the Ukrainian authorities, Israeli police officers used to fly to Ukraine specifically to monitor the behaviour of their fellow citizens. Local police also carefully patrolled the streets of Uman, trying to 41make sure that conflicts did not break out between residents and visitors. Nonetheless, every year some friction did arise – it was almost inevitable. After all, the Hasidim celebrate with a great deal of energy and noise, singing songs and dancing every night. They obviously like Uman and feel at home there, despite some tragic history and the memory of the pogroms, which are, indirectly, the reason for their coming.

This year, in view of the war, the Ukrainian and Israeli authorities have been encouraging the Hasidim to cancel the celebration of Rosh Hashanah in Uman. The threat of rocket attacks is very real. Also, there has been no civil aviation in Ukraine since the start of the war, making it impossible to fly to Kyiv. The borders in the west of the country are open, however, and trains and buses are running. Already the first thousand Hasidim have reached Uman by road. The international Flix bus company has introduced new routes to Uman, including from Kraków, Prague, and Brno.

In response to warnings about the danger, representatives of the Hasidim said that life in Israel is constantly fraught with the danger of terrorism, so they see no reason to change their traditions because of the war in Ukraine.

While Hasidim from Israel, New York, and elsewhere make their way to Uman, there are those who live in Uman permanently. They remember the early days of the war when Russian missiles fell on the city and nearby villages. At the beginning of the war, the number of Hasidim living in Uman actually increased, with many coming to help the local Jewish community, as well as the non-Jewish population, both permanent residents and refugees. A Jewish charity kitchen was set up which continues to feed everyone in need.

In late February and early March, shelling left many dead and wounded in the town. The basement of the synagogue was 42opened as a bomb shelter for all, whatever their faith. At the end of March, there was a real possibility that Russia would try to destroy the synagogue using rockets: the Russian Ministry of Defence announced that the Hasidim had given the synagogue to the Ukrainian army as an arms depot. “The property of the Jewish cult in Uman is deliberately being used by Kyiv’s nationalist regime for military purposes,” said Igor Konashenkov, Russian Defence Ministry spokesman. In response, the leaders of the Jewish community in Uman recorded a video showing the empty premises of the synagogue and other religious buildings and declared the words of the representative of the Russian Ministry of Defence to be a lie. Fortunately, no Hasidic shrines in Uman were damaged during Russian shelling.