19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

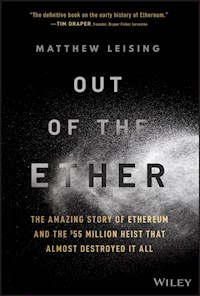

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Discover how $55 million in cryptocurrency vanished in one of the most bizarre thefts in history Out of the Ether: The Amazing Story of Ethereum and the $55 Million Heist that Almost Destroyed It All tells the astonishing tale of the disappearance of $55 million worth of the cryptocurrency ether in June 2016. It also chronicles the creation of the Ethereum blockchain from the mind of inventor Vitalik Buterin to the ragtag group of people he assembled around him to build the second-largest crypto universe after Bitcoin. Celebrated journalist and author Matthew Leising tells the full story of one of the most incredible chapters in cryptocurrency history. He covers the aftermath of the heist as well, explaining the extreme lengths the victims of the theft and the creators of Ethereum went to in order to try and limit the damage. The book covers: * The creation of Ethereum * An explanation of the nature of blockchain and cryptocurrency * The activities of a colorful cast of hackers, coders, investors, and thieves Perfect for anyone with even a passing interest in the world of modern fintech or daring electronic heists, Out of the Ether is a story of genius and greed that's so incredible you may just choose not to believe it.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 570

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Cast of Characters

Prologue

Part I

Zero

One

Two

Three

Part II

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Part III

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Part IV

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Sources

Appendix

Acknowledgments

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

ix

x

xi

xiii

xiv

xv

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

65

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

115

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

289

290

291

292

293

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

Out of the Ether

The Amazing Story of Ethereum and the $55 Million Heist that Almost Destroyed It All

Matthew Leising

Copyright © 2021 by Matthew Leising. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993, or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is Available:

ISBN 9781119602934 (Hardcover)ISBN 9781119602958 (ePDF)ISBN 9781119602941 (ePub)

COVER DESIGN: PAUL McCARTHYCOVER ART: © GETTY IMAGES | JOSE A. BERNAT BACETE

Dedication

For Rebecca, my life, my love. You always believed I could do this when I'd convinced myself otherwise. For that, you have my undying gratitude and thanks.

Cast of Characters

Ethereum Cofounders

Vitalik Buterin – Ethereum inventor, ringleader, onetime fashion maven, and lover of bunnies

Anthony Di Ilorio – Created Toronto's first Bitcoin meetup, early and important investor in Ethereum, later pushed out in a power struggle

Charles Hoskinson – One of the first five cofounders, wanted to lead the project from the start, fired after six months for abusive and manipulative behavior

Amir Chetrit – Met Vitalik in Israel working on colored coins project, unclear what he contributed to Ethereum, fired for lack of commitment

Mihai Alisie – Cofounder of

Bitcoin Magazine

with Vitalik, helped set up Ethereum's Zug headquarters, business development

Gavin Wood – Architect of Ethereum, C++ client creator, a bit prickly, took Vitalik's vision and made it real

Jeff Wilcke – Created Ethereum's Go client, sided with developers on power struggle question

Joe Lubin – Early and important investor in Ethereum, former software developer and Wall Street software engineer, true believer, user of strange words, founder of Ethereum development studio ConsenSys

Other important early people

Roxana Sureanu – Helped get

Bitcoin Magazine

off the ground, willing hardscrabble traveler, turned the Spaceship House from a dwelling into a home

Stephan Tual – Ethereum evangelical, ran marketing for the project, has the gift of gab, one of three founders of slock.it, added to Ethereum leadership after Zug purge

Christoph Jentzsch – Helped debug Ethereum code in run up to 2015 launch, theoretical physicist by training, co-founded slock.it, really wishes he could revisit line 666 in the DAO code

Mathias Grønnebæk – Helped establish Zug headquarters, reader of tax laws, worked for Charles Hoskinson, helped craft Ethereum Foundation business plan

Taylor Gerring – Helped secure Bitcoin raised in Ethereum crowdsale, taker of many photos, added to Ethereum leadership after Zug purge

Anthony D'Onofrio – Designer and software developer, helped improve early Ethereum web site, took drugs, saw future, one of the few people Gav Wood likes

Emin Gün Sirer – Blockchain pioneer, first to use proof of work to back a digital coin, Cornell associate professor of computer science, called unsuccessfully for a moratorium on the DAO then found the DAO bug and dismissed it

Peter Vessenes – Bitcoin pioneer, tangled with the Bitcoin Foundation, pointed out smart contract security issues

Ming Chan – First executive director of the Ethereum Foundation, whipped it into shape to keep it within its means, Vitalik favored her though she rubbed many the wrong way

Badass blockchain ninja warriors

Alex Van de Sande – Known as avsa, helped marshal the Robin Hood Group from his apartment in Rio, co-developed the Mist wallet, excellent husband, the one who pushed the button to start the DAO counterattack

Griff Green – The Mayor of Ethereum circa June 2016, hugger, visionary, driver of the RHG, slock.it's first employee, wants a sick jump shot but it's just not happening this time around

Fabian Vogelsteller – tech whiz who helped the RHG prepare to fight the ether thief, co-developed Mist wallet

Lefteris Karapetsas – coding guru, replicated DAO attack in a few hours

Jordi Baylina – helped the RHG drain remaining $4 million of ether from the DAO, coding genius, Spanish freedom fighter

Other really important early people

Dmitry Buterin – Vitalik's dad, supportive father, hater of communists

Natalia Ameline – Vitalik's mom, patient mother, adventurous spirit

Maia Buterin – Vitalik's step mom, patiently waited for Vitalik's cooking

Important people who helped Ethereum go mainstream

Amber Baldet – Hands-on builder, coder, vital within JPMorgan to link Ethereum to its in-house Quorum project

Christine Moy – Amber's first hire for Quorum within JPMorgan, finance master in all areas of the bank

Patrick Nielsen – Hired by Amber at JPMorgan, solved the privacy issue for the bank that gave birth to the Quorum ecosystem

Marley Gray – Microsoft director of blockchain and distributed ledger business development in 2015, lover of Andrew Keys, delivered on Microsoft's vision of “a growth mindset” by linking up with Ethereum

Alex Batlin – Ran UBS Labs, a fintech-focused unit at the Swiss bank, instrumental in creation of Enterprise Ethereum Alliance

Jeremy Millar – ConsenSys executive who helped create the EEA after realizing competition from R3 and IBM were real and needed a response

Andrew Keys – One of the first ConsenSys hires, worked for free, loaned $100,000 to the Ethereum Foundation to ensure Dev Con 1 took place, great explainer of complicated things

Prologue

The future was broken.

Every person in this story I'm about to tell you knew this. Felt it in their bones. Their views were well known and widely shared, yet nothing ever seemed to change. Capitalism was destroying the planet. Income inequality kept tightening its grip. Tech behemoths like Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Twitter owned the public square, where once all you needed was a soapbox to voice an opinion. Now any of these monopolists could censor you or shut you down for even clearing your throat. Human beings had ceded their organizing power to corporations that saw them as data to be harvested and sold. The grievances were long and detailed, and yet not many of these people could put their fingers on a way to effect change.

The future was broken.

A global financial crisis had robbed a generation of a decade of productive employment opportunity. The recent graduates in this story who looked out over the years ahead of 2008 saw no hope for economic growth, only job cuts and shrinking industries. The banks that created the fiasco, though, they got off. Hell, they saw their stock prices soar in the years after 2008 thanks to an unspoken but very real US government guarantee – take all the risk you want, we'll be here to bail you out when necessary. The people who lost their homes? Not so much. They'd have to fend for themselves.

The future was broken.

The Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan, a giant in media theory who changed the way we look at popular culture, warned us in 1967: “How shall the new environment be programmed now that we have become so involved with each other, now that all of us have become the unwitting work force for social change?” he wrote in The Medium Is the Message. “All media work us over completely. They are so pervasive in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical, and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered. The medium is the message. Any understanding of social and cultural change is impossible without a knowledge of the way media work as environments.”

Fifty years after McLuhan wrote those words, another writer had also been at work. Here was a rare individual, someone able to put a finger on the dystopia that sprang from so much concentration – concentration of power, of wealth, of media. All of it originated from centralization. The gatekeepers kept making the gates higher and higher and more and more costly. But what if we could create a system without gates, without a central authority and the power to say what is permissible? What if, the people in this story asked, the organizing principle instead was flat and distributed and no one had enough control to stop anyone else?

That's the idea Satoshi Nakamoto gave to the world in the fall of 2008. The creator of Bitcoin had seen the future, knew it was broken, but also knew it could be different. Bitcoin would fix the future, and it would change so much more than how people thought about money. It gave these disconcerted characters the elusive thing they sought – the key to unlock it. Blow up the center. Destroy the middleman. Take the power back. That was the idea, anyway.

And while this story must start with Bitcoin, it is not about Bitcoin. It's the story of what came next. It's about going beyond Bitcoin to use technology to build even more powerful connections among people. It's the story of Ethereum, a global network of computers known as a blockchain invented in 2013 by Vitalik Buterin, a Russian-Canadian genius who'd yet to celebrate his 20th birthday.

Buterin married the digital money aspect of Bitcoin to the almost unlimited capabilities unleashed by what can be written in computer code. If you think about it in terms of contracts, just about everything I can think of can be boiled down to a written contract. Certainly, legal documents, but also financial transactions, commerce, global trade. Now you could take those contracts and in a sense digitize them by bringing them to life on Ethereum's global network. Once there, they could be accessed by anyone in the world at any time of day or night. There's a money feature embedded in Ethereum too, so you can pay for stuff. And it all takes minutes rather than the days, weeks, or months to complete common transactions in the industries I just mentioned. The efficiency gains are on par with what the Internet provided us in the early 2000s.

At its most valuable, the Ethereum network was worth an astounding $135 billion. Its creators became billionaires and millionaires. Ethereum is – slowly – changing the way finance and mainstream corporations think about the myriad tasks they do behind the scenes to make the world work. This is the story of the people who brought Ethereum to life, and how they changed the world.

But it's also about a $55 million heist that threatened to bring Ethereum down. The DAO attack, as it's known, is one of the strangest tales of thievery I know. A group of good-guy hackers who called themselves the Robin Hood Group fought a ninja war on the blockchain to prevent hundreds of millions of dollars from being stolen. Against them was a malicious but ingenious attacker who for the most part remains unknown to this day. And finally, it's about my effort to find out who did it, to unmask the ether thief.

Part I

It is the business

of the future

to be dangerous.

– A.N. Whitehead

Zero

For most of the world the attack began on a Friday in June 2016. The planning and testing and tinkering had been in the works for weeks. Everything would have to be just right or it would fail. What was about to unfold was one of the most elegant, complicated, and weirdest thefts in history.

The clock read 3:34 in Coordinated Universal Time. That's the same as Greenwich mean time, for those who remember. The wee hours in Europe, still Thursday in New York City, and half past 11 in the morning in Beijing. A pair of eyes checked the screen again; a finger hovered over a mouse button. This was a moving machine with many parts: all interacting, all in code, all in cyberspace. It's baffling and complex, and some of the best computer scientists in the world struggle to put into plain English what happened. Robots attacking robots on the web. That's how one person put it to me, and I've never forgotten it. In this case the reward the robots battled over was immense – a quarter of a billion dollars.

None of this would have been happening if not for a new computer science discipline known as blockchain. While certainly a buzzword, blockchain is simply a new way of implementing databases. Instead of one company or government controlling access to data, the ledger is shared and spread among computer hard drives all over the world. It is what made Bitcoin possible.

Bitcoin, of course, ushered in the era of cryptocurrencies, a time where a new type of money came to exist, one that isn't backed by a government or bank but instead derived from whether people believe it's useful. Bitcoin was the pioneer, but by mid-June 2016, the second-most valuable cryptocurrency after Bitcoin was called ether. Ether is the fuel that allows the Ethereum blockchain to work.

The hacker looked at the contract he'd written one last time, then clicked his mouse. His target: a computer program that held $250 million worth of ether. What it also held was an enormous bug in its code that the hacker believed would let him walk right in and steal it all.

His first try failed. Four minutes later, he tried again. That attempt failed too – a red exclamation point next to his transaction declared “Error in Main Txn: Bad Jump Destination.” Shit, he thought he'd nailed this down. He took some time to check all the inputs, the addresses, and codes. Seventeen minutes later, at exactly 3:34:48 UTC, he tried a third time. Then, he saw it. His account had received 137 ether from the computer program that held the $250 million. That was a cool $2,700 he just stole.

The attack had begun. Thousands of these small transactions would accrue throughout the day as the theft continued. People all over the world watched as it occurred, helpless to stop it. Eventually $55 million of ether was stolen, making it the largest digital heist in history at the time.

●●●

I remember that day. I'd called in sick to my job as a reporter at Bloomberg News in New York. June 17, 2016. I'd wrapped some blankets around me as I sat on the couch in my Brooklyn apartment and checked my phone for whatever news I was missing.

I'd been at Bloomberg for 12 years, reporting on Wall Street and energy and oil markets, and then, for most of that time, my beat became the financial infrastructure that keeps the whole system humming but that no one talks about. How exchanges work, for example, or the ins and outs of US Treasury bond trading. Then the world went through the worst financial crisis since the Depression. I covered the Dodd-Frank Act's debate and passage: legislation written in hopes of reining in the financial world to stave off another crisis. I never thought I'd end up being a financial reporter – it just sort of happened, and then I found myself involved in one of the biggest stories of the century.

In 2015, all that background brought me to the realization that a new concept – blockchain – could radically change everything I wrote about. I'd dismissed Bitcoin as a fad for years. I didn't understand it. I thought, how in the world could anyone value something that was nothing more than ones and zeroes?

Blockchain, though, was different. Most of the financial plumbing I spent my days talking to people about was antiquated and in great need of updating. Banks like JPMorgan were sitting atop technology systems that would make the mazes of Babylon seem a snap to navigate. That's because they inherit IT systems when they buy other banks. And then they build systems in-house that might be designed according to the whims of a certain part of the bank, which then won't work with a system in another part of the bank. Some of these systems were written in Cobol, a programming language popular in the 1970s that faces the very real possibility that no one who knows how to fix it will be alive in a few years.

The best thing to do would be to rip it all out and completely redesign these systems. Which is impossible, of course. But Wall Street's need to catch up to the twenty-first century in terms of technology systems was critical. Blockchain turned many heads for this reason. Not only could it streamline bank IT systems, it held the potential of speeding up transactions, which would save banks a lot of money.

That's what I realized, thanks to a short article I read in the Economist in 2015. Soon after, I told my boss I wanted to include blockchain on my beat. He said, “That's great. What's blockchain?”

As I lay on my couch on that day in June 2016, the news hit that this thing called the DAO had been hacked. The DAO is the computer program I told you about, the one that held $250 million. I didn't use the name at first because I don't want to confuse you any more than absolutely necessary. I'll do my best to make this as painless as possible, but there are still going to be technical details. And names like decentralized autonomous organization, or DAO. Please – stick with me, hold my hand. We can do this.

So anyway, ether was being stolen, even as I read the story on my couch. I think I remember this vividly because I immediately experienced the pang of guilt any reporter feels when they are out of the loop as a big story is breaking on their beat. I should call in, I thought; I need to help tell this story. But I really was sick, and I didn't have many good Ethereum sources at that time.

In fact, earlier in 2016 was the first time I'd spoken to anyone about Ethereum. I went to visit Joe Lubin in the funky Bushwick headquarters where he'd started ConsenSys, the largest innovation studio for applications that would run on top of the underlying Ethereum network. An Ethereum cofounder, Lubin is quiet and demure. A native Canadian, he has an intense focus that can make you feel you have his entire attention when you speak with him. He shaves off the hair that remains on his head and is strikingly handsome in the way that some men pull off being bald.

Years before I met Lubin I'd lived in Bushwick. The Brooklyn neighborhood had been much rougher in 2004. Restaurants were few and far between. A bar called Kings County was one of the only local gathering spots and was just around the corner from where ConsenSys would later set up shop. I had friends at the bar who told stories of being chased by packs of wild dogs, of returning late to their apartment from the subway to find a tiny slip of paper jammed into their keyhole, put there by the guys in the shadows who demanded everything they had. It was an amazing time.

I knew the building ConsenSys would come to occupy, next to an overpriced natural grocery store. Its facade was forever covered in graffiti long before ConsenSys moved in, a detail no profile of Lubin or his firm has ever seen fit to leave out.

Lubin built ConsenSys in the hopes of fostering the types of digital applications that would make Ethereum indispensable to the world. Think of a blockchain-based digital version of Uber, but without the middleman that is Uber taking 30 percent of every transaction. Consumers pay less, drivers earn more, and hopefully the user experience of clicking an app on a smartphone isn't much different. Or think of an app that directly connects artists with their fans without a record company and lawyers and agents all in the middle taking their cuts.

What's amazing about this idea of a new kind of Internet that's peer-to-peer is that Ethereum has money programmed into it already. Ether is the currency of the realm, meaning that banks can't shut it down. Losing access to banking is almost always a sure way to kill off something you don't like. Here it's impossible.

But what does a blockchain Uber really mean? Let's run through it and call it CarCoin. This is how I first came to understand Ethereum's potential method of mass disruption.

How does CarCoin make money? That has to be the first question. No one wants to build complicated software for free. What you do is create a new cryptocurrency along with the application for your ride-hailing business. CarCoin will be created and sold to the public. Importantly, you must have a CarCoin balance to access the app on your phone.

Now imagine CarCoin hits it out of the park. Everyone wants some. The price of CarCoin goes up. The founders and developers of CarCoin, meanwhile, have made sure to give themselves a lot of CarCoin for free.

They do this in hopes that its value rises; then they're sitting on pure profit and all their hard work has paid off. This is smart contract 101 stuff once you understand the 360-degree nature of the ecosystem Ethereum's inventor Vitalik Buterin and his colleagues created. The app, the coin, and the supply demand dynamics all intertwine. It makes sense, yet I now understand it never really was the vision in the early years.

The people who invented and created Ethereum were flying blind. Very little of how the project became a reality followed any kind of thought-out process. That goes as far as making sure to have a way of making money.

Fabian Vogelsteller was an essential early programmer for Ethereum. Starting in about 2014 he built, with Alex Van de Sande, the Mist wallet, one of the earliest and most important Ethereum apps as it allowed users to access the Ethereum blockchain and hold the different digital currencies they owned.

“There was no business model at the time,” Vogelsteller said. The economics are rather limited, as he spelled out. You can't charge for using smart contracts and people are already spending ether to access Ethereum – that's fundamental. A digital application can only hope to earn money if it provides a useful service to people. But that was the last thing on early developers' minds, he said.

“We never thought about business models at all. It was only about what to build, not how to make money,” Vogelsteller said. I was speaking to him in 2020 for a story I was writing about his new project, Lukso, an arts, culture, and fashion focused blockchain based on Ethereum. I ran my CarCoin example by him, and he zeroed in on the big problem right away: Why is CarCoin – i.e., the new cryptocurrency – necessary? Why not just use ether for everything? It's taking the money aspect of Ethereum a bit too far to build an entirely new coin on top of it.

While this criticism doesn't blow a hole in the idea of digital applications, it does call into question the nearly two-year-long orgy known as the initial coin offering market that took place from about 2016 to early 2018. Billions of dollars were raised by legitimate and completely fraudulent dev teams alike. Everyone was welcome at this scamfest. And all of it can be seen in hindsight as an enormous waste of time, energy, and the little creativity that went into most ICO projects. It was a folly, but only one of many to come.

“The whole Ethereum community, from the core developers and on, is pure idealism,” Vogelsteller said. This sanguine vibe is strongly tied to one of the universally shared beliefs among the people who created Ethereum: the Internet should be free so we can all share it and build cool things, to paraphrase how Fabian Vogelsteller described it to me.

The correct incentives are the next ingredient in this idealism pie. Fabian compared it to a jungle: brutal, yes, but it all works because the incentives line up in favor of keeping the entire ecosystem healthy. Shitty incentives in the jungle lead to death for everything. Blockchain has to believe in incentives because its core function – to date, at least – is tied directly to the network of computers that mine and validate transactions. Making as much money as possible by mining comes with a nifty side effect – it provides the best security for a blockchain network. Greedy miners are wanted.

“In nature we have a lot of these systems” of aligned incentives, Vogelsteller said. “In society we don't believe it's possible, but blockchain shows it is possible.”

So does CarCoin work, or not? I wish I could tell you, but advances in crypto-economics aren't exactly whizzing about the industry. As far as I know, as of early 2020 the debate about incentives goes on without a clear answer. There are many problems Ethereum has to face if it's to become universal, not least of which is how people make money from it.

But the middlemen are still there and seem ripe for the taking. The speed at which Uber overtook the taxi industry was phenomenal. It just feels right that they could be disrupted in a similarly brutal and quick fashion.

In the world of finance the applications for Ethereum are particularly ripe, as Wall Street is – at its core – the insanely well-entrenched pure expression of middlemen profit-takers, making their money from other people's money solely by virtue of sitting in between transactions.

Joe Lubin wanted to build a different way of conducting business. He's a great evangelist for Ethereum. He's the one who first explained it to me and made the light bulb go off above my head. I've spoken to many other people who had the same experience with him as he laid out his vision of an Ethereum-enabled financial system. For me, when he kept repeating the words “global computer” I finally saw it and had one of those moments when you think, Man, that is fucking cool.

Yet all of this stuff was incredibly speculative. In 2016, the idea that Ethereum could be used in the financial world was only being discussed by a few far-thinking bankers. On the one hand, Ethereum promised the world, it was a hell of a story, but in 2016, in terms of what you could point to as an actual product, Ethereum had nothing to show.

When I cowrote a story for Bloomberg Markets magazine in 2015 about Blythe Masters, a former JPMorgan executive who was now heading a blockchain startup, I didn't even mention Ethereum. This is not a knock against Ethereum – I certainly could've known more about it at the time – but it's also true that it was simply too early to be taking Ethereum seriously in a financial markets' sense. So I didn't dig into the story of the $55 million hack when I went back to work. It was fascinating, yes, but for Bloomberg readers it didn't have enough of a connection to Wall Street or finance to justify me chasing it.

In the following months blockchain certainly didn't disappear from the headlines. There was plenty of hype, and I plead “no contest” to the charge that I contributed to it. But at the same time I felt that there was something there. People like Blythe Masters don't jump into things lightly, I told myself. Blockchain seemed to have some staying power.

Masters is what you would call Wall Street famous. She's beautiful and brash and ruthless. She rose within JPMorgan from being an intern in its London office when she was 18 to sitting on a trading desk to running bank divisions. She helped create credit default swaps, the derivative that allowed investors to bet on a bond's price decline. Credit default swaps also ensnared Wall Street banks and their customers in a wicked web of interdependency during the financial crisis that required the Fed to step in and bail out the financial system. Everyone on “the Street” knows who Blythe Masters is.

There were also other big names taking blockchain seriously, like the Bank of England and the World Economic Forum. This helped me take it seriously too, and then near the end of 2016 the editor of Bloomberg Markets, Joel Weber, said he was planning a heist issue for the next year. Did I have any good heist stories?

Oh, man, did I.

●●●

I love complicated things. I love the process of figuring out how things work and then describing them to people in a way they can understand. I know for sure this trait allowed me to carve out the niche I have within Bloomberg News. When I started learning the details of the ether hack, I realized that I'd stumbled upon one of the most convoluted yet brilliant stories I could ever hope to untangle.

Metaphors will be our friends in this story. Imagine it this way: a bank has been built underground, with a central vault that holds $250 million. The design of this bank is such that once built, nothing about it can be changed. Not its layout or its vault or how any of its banking processes work. Its banking processes are weird, but we'll get more into that in a bit.

This bank has thousands of customers, the depositors, whose money makes up the $250 million. Now, under the rules of this bank, if someone wants to get their money out, they have to tell the bank 7 days ahead of time. During this week the depositor creates a small room underground near the vault. Once that's done, they have to wait for another 27 days. Let's say that it takes the bankers that amount of time to tunnel to the small room so they can deliver the money to be withdrawn.

If all goes according to plan, the money is delivered to the small room, a staircase appears, and after 34 days the customer can climb to the surface with his cash. But what if there is a flaw in the design of this bank? What if once the request to create the small room is made, the customer turns evil and realizes that they can dig a second tunnel from their room that leads back to the vault? Because of the flaw there are no security guards to block this second tunnel and it leads straight to the money in the central vault. Once the digging was done the evil customer could start grabbing as much cash as possible, like a game-show contestant in a chamber with $100 bills flying all around. Because the bank design can't be changed, the flaw that allows for the second tunnel is part of the bank, a glaring hole that customers can exploit.

That's basically what the DAO hacker accomplished, only using computer code instead of a shovel.

I spent months reporting on the hack for the magazine. It was the most fun I'd had in my career. I met and got to know almost all of the people quoted in this book during that period. We called the article “The Ether Thief,” a nod to the great New Yorker story “The Silver Thief,” which Joel Weber gave me to read for inspiration. And yet all through the reporting for the magazine story, no one I interviewed said they knew who had pulled off the heist. The ether thief's identity remained a mystery.

One of the more amazing attributes of blockchain systems is that all of the transactions I'm describing are publicly viewable. This has been the case since Bitcoin was first mined in early 2009, and it's the case with Ethereum. People often claim that blockchain allows users to remain anonymous, but this is wrong. It's pseudonymous, because it's possible to know the identity of the person behind an address. Once that link has been made, a person's activity is traceable for anyone with an Internet connection. But it's rare to know who is behind any given address. And so most of the time we have no idea who is doing what on the Ethereum blockchain. In the case of the DAO, one of the main attack addresses was 0x969837498944aE1dC0DCAc2D0c65634c88729b2D.

But who is that? Even though we can see on the public Ethereum blockchain that this address received 137 ether at 3:34:48 UTC on June 17, 2016, and that hundreds of similar transfers were then made over the next several hours, we have no way of knowing the person behind 0x969837498944aE1dC0DCAc2D0c65634c88729b2D.

It always gnawed at me. The ether thief was out there, and no one knew who they were. It also seemed, after not much time had passed, that no one even really cared anymore. I wanted to change that.

●●●

The first time I met the ether thief was two floors above a Foot Locker in Zürich, Switzerland.

That's probably not how my employer would want me to describe our Zürich bureau, but it's true. I felt nervous in a way I'd never felt before an interview. I wondered if the person I was about to accuse would become angry or violent. I wondered if they'd break down and tell me everything, if they'd feel that the burden of their story and what they'd done could finally be unloaded. I didn't know how I was going to ask small questions at the beginning until I was ready to show the person the evidence I had. It was a Tuesday in September, a beautiful day in Zürich, and I couldn't tell if my hand shook from the coffee I'd had or if I was scared.

The man across the table from me wore glasses and a plaid scarf. He was maybe in his late 50s and had lost some hair. Swiss by nationality, he'd spent his career in Zürich or thereabouts. This part of the world is known as Crypto Valley for its early role in many digital token startups, Ethereum central among them. The technical university in Zürich is known as ETH, the abbreviation for ether, which is just a delicious coincidence. The Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich is a hotbed of blockchain research, and Albert Einstein was both a former student and a professor of theoretical physics there. It made a certain amount of sense that someone who had brought Ethereum to its knees with the DAO attack would be based in its backyard.

We spoke about his background in banking, and how he grew bored with it and wanted out. Bitcoin had enthralled him, like everyone else in this story, because of how it had created its own independent monetary system without asking permission or giving a care about what anyone thought. Ethereum had been smart to base its operations in nearby Zug, he said, as in 2014 or thereabouts the Swiss regulators and tax authorities treated crypto projects very favorably. He told me that he mined Bitcoin back when you could do it with some high-powered hardware. If he'd kept all the Bitcoin he mined, he'd be a very rich man and wouldn't be talking to me right now.

He spoke English well, with a dose of a German accent. The conversation turned to the DAO attack and what he remembered of it. Then I asked him if he had a theory about who did it.

He paused and smiled.

“Next question,” he said.

I laughed because he'd been speaking quite freely up to that point. “I have more than a theory,” he said. “It's not that difficult to figure out.”

This was possibly the first person to ever say that to me about the hack. It was incredibly hard to figure out, in fact, as I had learned in my previous reporting for the magazine story and this book. The ether thief had covered his tracks meticulously.

Yet here I was sitting across from a person who for years had only been described to me as someone who lived in Switzerland. When researching the “Ether Thief” magazine story in 2017, the Ethereum people who suspected this man wouldn't reveal his name to me. It was rather cute, I thought at the time, and indicative of the ethics held by many in the Ethereum community: they wouldn't help spread the rumor that this man had been involved because they didn't really know if he'd done it.

In journalism, however, it's all about finding the right sources – the people who know the story. And I'd been lucky enough to find one such person. Exchanges are one of the only institutions in crypto that know the identities of their customers, and not even all exchanges do: some let people get an account and trade on their platforms with only an email address. But my hunt for the right source led me to someone who worked for an exchange. The names of three people in the Zürich area were shared with me by this person, along with transaction links from the exchange to their Ethereum transaction histories, links that pointed to the DAO attack. The man across from me was thought to be the leader of the group, I'd been told. I was enthralled, and yet knew this was almost certainly unsolvable. I only had a sliver of the whole story as I sat across from him. I would need him to confess to be certain.

Still, there were a few clues to this mystery and I'd discovered one.

●●●

There would be no DAO without Ethereum, just as there would be no Ethereum without Bitcoin.

And none of it would have existed without the Internet. Possibly the most tantalizing ingredient missing from the World Wide Web is money in purely digital form. For all that the Internet has enabled, it has fallen short in creating a form of value that can be sent around the world as easily as email. It's not as though no one thought of this, however – there was a realization early in Internet history that digital money should be a feature.

In the 1997 Internet Official Protocol Standards, which specifies various aspects of the html protocol that makes the Internet possible, you can find entry 402, designated “payment required.” This is the code that would've created a field to fill in on a web page with the type of digital money you'd be using to buy the latest Sex and the City DVD. It would have embedded digital payments into the DNA of web pages right alongside graphics and text. Yet for many reasons, it never happened. In the more detailed part of the protocol standards, entry 402 receives a harsh dose of reality: “This code is reserved for future use.”

It would take just over a decade before status code 402 passed the baton to Bitcoin. It was not for lack of effort that digital payments hadn't come along until 2009, though – there were many projects over the years that came close. Which is to say, there were people all over the world who craved a form of digital cash. What the mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto did was bring together a set of existing technological pieces into one design that finally solved the puzzle.

Bitcoin looked like freedom. In its purest form, Bitcoin brushed aside any political or social biases when it first gained popularity, leaving its early adherents with nothing but gleaming possibility. Thousands of people all over the world needed Bitcoin for no reason other than it gave them hope for the future again. It made them quit their jobs, invest all of their life savings, or sometimes both, to ensure that this thing succeeded.

What Bitcoin did was to finally present a competitor to the global banking sector. Banks serve a host of purposes, of course, from granting loans and mortgages to making most everyday payment transactions so convenient that a swipe of an ATM card is all that's needed. But for a subset of people, the fact that banks are gatekeepers that can restrict or prohibit certain transactions has always been a big problem. A strong strain of libertarianism ran through early Bitcoin adopters, who wanted to exist outside the traditional financial world.

One of the keys to how Bitcoin works is its hash function. When the latest batch of transactions is sent to the computers in the network for validation – these are the miners – the block comes with a random string of characters associated with it. The miners take this random string and work through trial and error to change it so that it has a certain output value when it's run through the hashing function. In Bitcoin, that output is one that leads with a certain number of zeros. The only way to do it is to add one thing to the input, see how it changes the output, and then try again and again and again until the output has the right number of zeros in front.

Once the input is changed in the correct way, it's a simple operation for the other computers in the network to check the output to see that it's genuine. So it's very hard to produce, but very easy to check. The process also uses a certain amount of electricity to run the hashing hardware, so economic value enters the equation in the form of the cost of that electricity. That's hashing in Bitcoin, and it allows for trusted transactions to take place among users who neither know nor trust each other. And for all their willing effort, the winning miner is rewarded with free Bitcoin.

All of this lives entirely free and clear of Wall Street and government regulators. That's a big key to why Bitcoin is valued as it is. People want it to have value; they want it to work and exist in a world wholly separate from Bank of America ATMs as well as governments and their central banks that set monetary policy.

The big strike against Bitcoin, however, is that it doesn't allow for derivatives. Bitcoin is all Bitcoin is about. It's an amazing thing for what it does, and as of this writing it's been doing it for more than a decade without any person, corporation, or government being able to stop it. But if you want to do more with a global distributed network of computers, Bitcoin can't help you.

That's why Ethereum sprang to life. Ethereum is entirely about the derivative, about being a blockchain system that will support all the weird, amazing, and crazy things people want to build on top of a global digital programmable payment network. As Ethereum cofounder Joe Lubin put it to me, Ethereum's ambition is to be a global computer. In a statement that surely upset Bitcoin loyalists (and there are millions of them), Lubin said that comparing Bitcoin to Ethereum is like comparing a pocket calculator to a desktop.

What I'm about to say now will make some of you laugh, but bear with me. Ethereum is the most successful blockchain in existence. I say that with Bitcoin only a shade behind its younger sibling. Yet in my opinion it's the restrictive nature of Bitcoin that places it second. Ethereum took the distributed security and robustness of Bitcoin and opened a world that allows computer programmers to build whatever they can dream of on top of it. I believe in Ethereum – I'm writing a book about it, for God's sake – but I also know its flaws. I will tell you about them. But as of early 2020, here's what Ethereum has accomplished in brief:

At its highest price in early 2018 the value of ether was above $1,400, giving the entire network a market cap of $135 billion and making billionaires of early founders like Vitalik, Joe Lubin, Anthony Di Iorio, and others. It made millionaires out of hundreds more.

JPMorgan Chase, one of the largest and most powerful global banks, is building its blockchain system on a slightly tweaked version of Ethereum and is creating the bank's own digital currency it has dubbed JPMCoin.

Ethereum didn't allow only for the creation of ether, its own native digital currency, it created a new way for startups to raise money, a process known as an initial coin offering, or ICO. This is an enormous advance in funding, as it allows crypto projects to sell tokens directly to the public, sidestepping any bank or venture capital involvement. While billions have been raised through the ICO market since 2016, it has been rife with scams, fraud, and outright theft.

It spawned a host of competitors like EOS, Stellar, Cardano, and Ava, which took the smart contract structure and tweaked it to make transaction times faster or added different security protocols. Yet none of those projects can compare with the number of developers working on Ethereum. According to a 2019 study by Electric Capital, Ethereum has four times as many developers working to maintain and improve its network as the number of devs working on Bitcoin.

Reddit, one of the most popular destinations for US Internet users, integrated Ethereum smart contracts and wallets into its service in 2020 to grant “community points.” These can be used as a type of reputation metric, as they're given for posting and contributing to reddit discussions. The points are stored in an Ethereum wallet, which could lead to a significant jump in Ethereum users.

Financial markets are now using Ethereum in real-world trading and settlement for assets such as stocks, credit default swaps, bonds, and equity derivatives. The Bank of France used Ethereum to replace a key component of its payment system.

As of June 2020, the value of all ether in existence totaled $27 billion, making it the second-most valuable digital currency behind Bitcoin, with the ether price at about $242.

●●●

Ethereum was invented in 2013 by a 19-year-old named Vitalik Buterin. He was familiar to the Bitcoin community at the time as the cofounder and head writer of Bitcoin Magazine, where he penned well-written stories on all aspects of the technology. Buterin possesses the type of towering intelligence that forces people to describe him in otherworldly terms, an alien sent from the stars to live among us. He sort of looks like an alien, too. His head is too big for his body, sitting atop an elongated neck. He's long limbed and has a bit of a mechanical gait. His voice can register in flat, almost computer-like tones at times, though when he laughs in quick bursts his voice deepens. His large blue eyes can be piercing if he takes the time to look at you as he speaks, which isn't often. He has an unmistakable presence: you could spot him across the most crowded conference space. His fashion sense for many years led him to lean toward rainbow T-shirts with pictures of unicorns or Doge, the Shiba Inu dog mascot of the cryptocurrency Dogecoin.

There is a whimsy about Vitalik that not many people get to see. He has a sharp wit and is quite funny. We met in Seattle; Ithaca, New York; and Los Angeles to talk for this book. He was incredibly generous with his time, once I could get on his hectic schedule. He doesn't know how to drive and on average is on a plane once a week. Wherever he lands, he tends to stay from between three days and three weeks. He has no permanent home, though his family all live in Toronto. Like any inveterate traveler, he has his routine down to a science. He packs a bag that measures forty liters in volume. Contents: seven T-shirts (a few long sleeved); seven pairs of underwear; seven pairs of socks; sweater; jacket; spare pants; toiletries; a spread of foreign currencies; and public transport cards for Toronto, Boston, Washington DC, San Francisco, London, Tokyo, Seoul, Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Taipei, Singapore, Bangkok, and Sydney.

He is frugal to an almost ridiculous degree. In high school his dad couldn't convince him to buy a new pair of shoes when his were literally falling apart. Through his early involvement in Bitcoin and then as the inventor of Ethereum, the cryptocurrency fortune he's amassed has at times been in the billions, though he demurs when asked for a specific figure. Yet through the first part of the journey he took across the US and Europe as he formulated the ideas that would become Ethereum he limited himself to a budget of $20 a day. As that level of restraint implies, Vitalik is also fastidious. At one interview we were sitting outside at a café on the Cornell campus, speaking of his fellow cofounder and friend Mihai Alisie. Vitalik peered across the table to my notebook and let me know I'd spelled Mihai wrong.

There is a humility to Vitalik that I find extraordinary and admirable for someone with so much influence and power. He has a joy to him that might come from being independently wealthy – or maybe that's just who he is. After we met at the Washington State Convention Center – Vitalik was speaking at Microsoft's developer conference – he got up from the table, crumpled his paper cup in his hands, and leapt into the air. He kicked his feet out just a touch as he sank the shot in a nearby trash can.

●●●

Vitalik wanted to give the world a way to build whatever its heart desired on top of his blockchain. Two things were necessary to make this possible: smart contracts and ether, the cryptocurrency that must be used to pay for every Ethereum transaction.

In the most basic sense, smart contracts are what separate Ethereum from Bitcoin. Bitcoin is used to send value from person A to person B. It's linear. Vitalik wanted to be geometric, to create a system that could involve however many participants were necessary, linking A to B to F to K to G and then back to A. A way to do that is to have computer programs that are tied to and follow the rules of a blockchain system. That allows the various inputs to the program – the data – to change the state of the system.

Okay, wait. What the hell does that mean? Smart contracts are like a store: let's call it 7-Eleven. Think of all the things you can do in a 7-Eleven. We'll call you Electron Girl, because that's what you are – all blue and sparky, sending out lightning bolts from time to time. As you make your way through the store (let's say you're in Tokyo, which has the best 7-Elevens in the world) you can buy some sushi or get money from an ATM or talk to a friend or look at the magazines until the guy behind the counter yells at you. When you pay for your sushi at the register, you might get a receipt, but if you pay in cash there's not much of a record of the purchase.

All the various things you just did at 7-Eleven you can do digitally while interacting with a smart contract. The programming to secure the purchase of the raw fish is written in code that lives within the smart contract – we buy things in such an automated fashion online every day.

Talking to your friend is just a chat function. And the library (maybe the digital Library of Congress one day?) is just over there. Your digitized self runs through this routine by engaging different Ethereum-based applications that use smart contracts. I don't mean to leave the impression that one smart contract runs the entire 7-Eleven; you engage different, discreet contracts for each interaction.

So, what's this part about changing the state of the system? It's simple: it's just the recalibration of funds – for example, when you got cash from the ATM. Your wallet now has $40 in it, while the bank is less the same amount. And, oh yeah, you're reminded that you owe your friend 20 bucks, so you pay up. In Ethereum, paying your friend can be as simple as reading a QR code from his phone. The digital wallet where you keep your ether, where the original $40 value is stored, is now lighter by $20. The state of that environment changed and the blockchain updates to keep track of it.

In this scenario, Bitcoin can only be used to buy your sushi. You can't talk to your friends or read Moby Dick while using the Bitcoin blockchain. You can using Ethereum.

Much more complicated systems are also possible. It's not unrealistic to say that almost the entire global oil market could be shifted onto Ethereum using smart contracts. Oil output could be monitored and secured on the blockchain. Private trading would be simple to set up because of the small number of participants. What Ethereum is not yet ready for is the speed at which electronic oil markets, like the crude futures traded at the New York Mercantile Exchange in New York, work. Yet OPEC production cuts or gains would transmit via an automatic information feed to the Ethereum network via what's known as an oracle. The oil tanker industry could move its supply chain to Ethereum as well.

Again, I think about it in terms of generic contracts. You made many contracts in your 7-Eleven adventure, even though we don't think of talking to a friend in those exact terms. But conversation is a contract. Now imagine those contracts are on Ethereum. You engage the blockchain differently than how we go online today, no doubt about it. Yet in many ways it's not that far from what we do today when we interact with the web.

These types of transactions are bread and butter for any computer, but until Vitalik came along they hadn't been coupled with a decentralized network. Smart contracts can handle thousands of inputs and outputs, and as long as the code is clean they can live on indefinitely.

Access to such a system, though, has to have a price. This is where ether enters the equation. Vitalik knew that there would be people who would want to try to overwhelm Ethereum, to slow it down or even break it entirely, by spamming it with thousands of simultaneous transactions. If they wanted to do that, they'd have to pay a hefty fee in the form of ether. Gas was the main idea here, like what you put in your car. No gas, no go.

That means ether would have an inherent value, as it's vital to how Ethereum operates. Whether that value was 10 cents or $1,000 would be up to the people who wanted to use it.