10,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ithaca Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

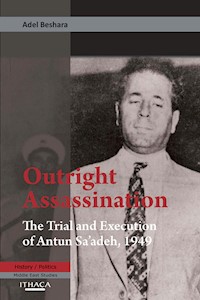

No other political trial in Lebanon and, indeed, the Arab World has been more controversial than the trial and execution of Antun Sa'adeh just before sunrise on July 8, 1949. The case is inescapably a tragedy. It was and still is the shortest and most secretive trial given to a political offender. Indicted for treason and for creating dissension, Antun Sa'adeh was tried on trumped-up charges based on falsified evidence and deliberate misapplication of the law. It was really nothing more than an open-and-shut exercise in accusation and punishment - a trial more appropriate to the cruel days of the Middle Ages than the supposedly civilized world of the 20th century. Since the trial was held, many complex issues have been raised, many more crucial than the actual fate of the accused: Why the secrecy and haste? Was it a fair trial? Was the offence political and, if so, why did the Lebanese State refuse to treat it as such? What did the Khoury regime hope to achieve from the trial? Did the penalty fit the crime? This book answers these and many more questions that until now have received cursory treatment as part of a general history rather than the thorough analysis they deserve.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

Outright Assassination

The Trial and Execution of Antun Sa’adeh, 1949

.

Adel Beshara

.

.

Outright AssassinationThe Trial and Execution of Antun Sa'adeh, 1949

Published by Ithaca Press 8 Southern Court, South Street Reading, RG1 4QS, UK

www.ithacapress.co.ukwww.twitter.com/Garnetpubwww.facebook.com/Garnetpubblog.ithacapress.co.uk

Ithaca Press is an imprint of Garnet Publishing Ltd.

Copyright @ Adel Beshara, 2010, 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

First Paperback Edition

ISBN: 9780863725333

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Samantha BardenJacket design by Garnet PublishingCover photo reproduced courtesy of Badr el-Hage

Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press: [email protected]

Dedicated to the cause of truth and justice

PREFACE

This study is a history of the trial and execution of Antun Sa’adeh (1949), the shortest, most secret, and most obscure “event” to take place in independent Lebanon. Its dramatic and political significance stems not only from the acceleration of its procedure, during which the greatest moral and legal values were crushed and violated, but also from its lingering effects on Lebanese politics. Yet if the Sa’adeh event was typical among similar events in history, in two other important respects it was quite unusual. First, unlike all previous and subsequent trials in Lebanon, and indeed the Arab World, the Sa’adeh trial defied human logic and the legal norms that govern proceedings under similar circumstances. Second, although the Sa’adeh trial was a political trial in every sense of the word, widely regarded as a pre-orchestrated political exercise, the Lebanese government refused to treat it as a political event. It decided to schedule a courtroom drama, with at least the embroidery of legality, under the criminal law in order to facilitate the use of the death penalty. This book is thus an examination of how the Lebanese State tried to grapple with a political case by means of ordinary criminal law. How did this effort work in detail? What were its strengths and weaknesses, its limits and boundaries? What were the legal and political ramifications of using the law for political purposes?

This book chooses to address these questions by means of a detailed history of the saga. The mechanism of the case, the stage machinery of its enactment, the parts played by those who serviced that machinery, and the politics that triggered it are carefully reconsidered and examined. In the process, the study will raise a number of fundamental issues relating to the nature of the trial, discuss whether it was a political trial or not, and determine why it was steamrolled with unprecedented speed. A secondary emphasis of this book is to stimulate issues worthy of additional investigation beyond the confines of present official and non-official accounts in the literature.

As for the book’s structure, it falls roughly into three main sections. In the first section some background to the saga is given with the main focus being on Sa’adeh’s political views, struggles, and conflict with the central authorities. The second section is concerned with the most “private” aspect, the actual Sa’adeh Affair – trial, execution, and procedures – with special emphasis on the political and legal particulars of the case from the perspective of both domestic and international law. The final section deals with the post-execution stage. It presents a critical and historical analysis of the reaction to, and consequences of; the execution, and an outline of the various scenarios that have surfaced to explain why it happened and who may have been involved and their motivations. Although some of these topics have been dealt with before, a comprehensive analytical approach has rarely been attempted.

The main sources are records from various domestic and overseas archives, the Lebanese press and periodicals at the time, past and present studies, and the personal accounts and memoirs that have come out in large numbers in the last two decades or so. Notwithstanding their apologetic nature, these memoirs provide valuable insight into Lebanon’s politics and constitute perhaps the liveliest and the most interesting portion of the literature on the Sa’adeh affair.

As with every study there were restrictions. We have no transcripts, no court records. We do not hear the prosecution or the defendant. We know the story only as told later by individuals who were around at the time. The trial transcripts disappeared after the trial in 1949 and have never been found. The author attempted to retrieve them in person from the archives of the Military Court in Beirut, but to no avail: they smoldered during the 1982 Israeli invasion, so said the officer-in-charge. To our knowledge, some fragments of the transcripts were published inThe Case of the National Party, a manuscript put out by the Lebanese government at the end of 1949, but they are extremely inadequate. The manuscript as a whole conveys the proceedings in a highly condensed and one-sided form. It is an utterly indigestible book.

I am well aware of the great disadvantage caused by my inability to consult the trial transcripts and other source-material directly on the case. I tried my best to minimize the damage by drawing heavily upon memoirs of Lebanese statesmen and the press. I hope that one day this discrepancy will be made good. Until then my conclusions cannot be regarded as final even by myself.

No book is written in a vacuum. I would especially like to thank Dennis Walker and Jabr Abdul-Fattah (Bahrain) for their help in translation, Richard Pennell (Melbourne), John Daye, Riad Khneisser, and Amal Kayyas (Beirut), Badr el-Hage (London), and Michel Hayek (NDU) whose comments and guidance have been invaluable. I also owe a great debt to numerous colleagues and friends in Melbourne and in Lebanon who read parts of the manuscript and gave me the benefit of their experience and insight. Needless to say, the views expressed in this book and any faults or shortcomings are solely my responsibility.

Numerous libraries have assisted, more or less knowingly, in providing me with resources. The work of research would be vastly longer and more trying if it was not for the patience and kindness of librarians. My thanks go to staff at the following libraries: Jafet Library at AUB, the Notre Dame University Louaize Library, and Baillieu Library at Melbourne University.

.

INTRODUCTION

At ten precisely on the night of 6 July, 1949, Antun Sa’adeh walked into the Presidential Palace in Damascus for a pre-scheduled meeting with Husni al-Zaim. He was alone – no personal bodyguards, no aides, only the Syrian Chief of General Security, Ibrahim al-Husseini, with him. No sooner had Sa’adeh entered the main foyer than twelve armed guards quickly formed a half-circle around him to block his view of the outside world. No one uttered a word. There was no need. The message was loud and clear and the first to understand it was Sa’adeh. “I get it”, he uttered, with a gentle smile on his face. The scene could easily have been mistaken for a Hollywood production if the characters hadn’t been speaking in Arabic. Mission accomplished, al-Husseini calmly departed and Premier al-Barazzi walked in from another door at the other end of the foyer. Without any formalities al-Barazzi called out to Sa’adeh, “You have a score to settle with Lebanon. Go take care of it.”1With those words Al-Barazzi inadvertently provided the setting for the most sensational legal case of post-WWII Lebanon: the case of Antun Sa’adeh.

As in all good dramas, the Sa’adeh case abounded with ironies. It was short, swift, and very secretive, the entire procedure lasting only thirty-six hours. It was over before it even started. Just about everything about the case was pre-orchestrated – the charges, the evidence, the tribunal, the sentence, the punishment. As it proceeded to its conclusion, other unusual features about the case hid behind a façade of mythical and legal rituals. These were carefully concealed through various instruments so that no detailed reports of the proceedings would reach the public. No one was to learn about the defiant posture of the defendant or about the charges against the regime. It was simply a trial where the government was reluctant to focus on the question of rightness, only the legal issue surrounding the broken law.

The best that can be said of the trial is that it was a typical drumhead court-martial. Every step in the proceedings was improvised: the judges were either incompetent or non-neutral, the prosecutor was also a judge, the evidence was pre-fabricated, and the accused was presumed guilty from the outset. The outcome of a drumhead court-martial is usually execution by firing squad, and that unerringly was the outcome for Sa’adeh. Yet even the execution process was an administrative nightmare. The state sought to make an example of Sa’adeh as a warning to like-minded individuals that a similar fate could overtake them, but it went about it in the most objectionable way. As it did in his trial, it broke every law in the book to have him executed before daylight.

For this reason, the Sa’adeh case has been given several pointed descriptions: a parody of justice, an accelerating tragedy, a pitiful comedy, a shameful blot. Ghassan Tueini, the editor-in-charge of the popular Lebanese dailyan-Nahar, called it “murder.”2With equal profundity and depth, Tueini went on to say:

The authorities have succeeded in arresting Sa’adah, giving him a speedy trial, sentencing him, and executing him, in such a speed which left most people dumbfounded and bewildered. It was difficult to comprehend the reasons for this most unusual and un-called for action, especially that the rebellion was successfully and swiftly suppressed. Even Sa’adeh’s arch-enemies were at a loss of words to justify the Government’s action. Those same enemies are now saying, “What a great tragedy”. Although the Government wanted to get rid of the man as speedily as possible, fearing he would bring terror to Lebanon, yet, by its rash action it has created a great giant, stronger than Sa’adeh ever was, and has made of him a martyr, not only to his followers but to those who never wished him better than death.3

None, however, could match the description of Edmond Rizk, former Lebanese Minister of Justice. He called it “outright assassination” (“Un assassinat pur et simple”).4

The present study is a critical and historical analysis of the Sa’adeh saga, the most dramatic and politically resonant trial of post-independence Lebanon. It is a detailed account of the events leading to it, its salient issues, its history and outcome, and its repercussions. As it progresses, the study will tackle a number of substantive issues relating to themotives and deeds of the main participants: What were the domestic backgrounds of the saga? What was the role of regional powerbrokers such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia? To what extent did international politics influence the trial? What role did Premier Riad Solh play and did he act alone? Why was the trial held on camera and not as a public show trial? Wherein lay the similarities and the differences with other political trials and where do they interconnect? How was the accused treated and how was the scenario drawn up? How was the outcome received and why did its repercussions become uncontainable? Was it a political affair? It is the purpose of this book to answer these and similar questions, insofar as the facts permit an answer.

Although some of these topics have been dealt with before, a comprehensive analytical approach has rarely been attempted. Current scholarships, including those directly on the Khoury era (1943–1952), at best provide a cursory treatment of the saga as part of a general history rather than the thorough analysis it deserves. This approach allows more focus and the inclusion of specific details, but it loses sight of the larger arena in which it happened and ignores the process by which politics overlap, compete and clash, drown or reinforce each other in legal controversies. Indeed, it is exactly in this dialectical process that the Sa’adeh saga should be examined and can best be understood. Moreover, most analyses rely on crude stereotypes within a chronological approach. To gain a fuller understanding of the saga, however, it is important to examine simultaneously other variables such as regime and individual participant behavior – their minds, motives, morality, deeds, and standing under international and domestic law. A multidisciplinary approach is necessary because legal-political controversies occupy an intermediate position between the spheres of politics, religion, culture and psychology, and understanding the part is impossible before one understands the whole.

If, however, it is necessary to recognize the variability of Sa’adeh’s trial across time, as well as to situate the saga in its proper political and legal context, then such detailed individual histories are urgently needed. These works, when taken together, enable us to begin to piece together the political background to the saga and its significance for postwar Lebanese history. What remains necessary above all, however, is to begin to embed these insights into a more comprehensive understanding of the nature of Lebanese law and political system, and ofthe Lebanese Republic in the 1940s. To understand the Sa’adeh saga properly, one must also understand the tumultuous relationship between Sa’adeh and the Lebanese state more generally.5

As one of the most tragic incidents of the period, the Sa’adeh trial and execution enlivens histories of the early independence era, but does it merit serious historical investigation in it own right? We have answered “yes.” First, an examination of the saga provides many opportunities to cast light on an obscure and neglected period, to date mostly unexplored, of modern Lebanon. It helps to widen the framework in which the Khoury regime should be considered and to evaluate its significance in several intersecting contexts. There is much to learn from the saga about the Lebanese political system, its workings, and its performance under conditions of strain. Moreover, by reconstructing the saga along with the events leading up to it we can instinctively gain a number of insights into the character of Antun Sa’adeh, a person who achieved a great reputation through his writings and revolutionary activities,6and into the much-misunderstood politics of the Syrian Social National Party and other active participants.

Second, as an historical event, the Sa’adeh saga has much to offer those who keenly follow and study political trials. Inquisitors will find themselves in the presence of a case that had all the trappings of a political trial, whose course was dictated by definite political aims, and whose conduct was thoroughly political yet calculatingly staged under a non-political law. Thus, the jurisprudence of the case is useful both for legal and political inquiry, particularly regarding the intractable question of why governments react differently to similar circumstances or would attempt to avoid a political trial if they think that the exercise is too cumbersome. The Sa’adeh saga is also useful for testing several hypotheses about political justice: Is there such a thing as a political trial? What are its main attributes? What is a political crime? Is a political trial better perceived as politics or as law? What is the difference between what is properly politics and what is properly law? What should a court do when confronted with a case that questions the legitimacy of law itself? Is law legitimate only when might does not make right? Is power its own authority in politics? Is a political trial a disease of both politics and law, or can a political trial affirm the rule of law? Can a political trial make a positive contribution to a democratic society?7 As a case study in political justice, the Sa’adeh sagais especially pertinent to Otto Kirchheimer’s theory of how governments use the law for political purposes.8

Third, as a subject for appraisal, the Sa’adeh saga is protean. A lawyer will view the trial as the focus of many novel and difficult legal questions, both substantive and procedural; the political scientist will perhaps see it as a fascinating study of a constitutional democracy in reversal; the historian will find chief value in the wealth of information –both official and personal – which the trial brought to light, and in the recollections and commentaries of the participants and politicians and officials and other leading figures in the era of the Khoury regime. All scholars and professional men will find much of interest and value in the politics preceding and following the saga.

The importance of the Sa’adeh saga was immediately recognized by contemporaries. In addition to the massive press coverage that appeared shortly after its conclusion, there has been over the years an outpouring of books and monographs about the event. However, it has been mostly in Arabic and often either rather cursory or polemical. The one exception in this regard is Antoine Butrus’ celebrated bookQissat muhakamat Antun Sa’adeh was i’idamehe(An Account of Antun Sa’adeh’s Trial and Execution).9Yet, despite the admirable thoroughness of the book, a great deal of work remains to be done. Butrus’ book is the starting point for all future research in the sense that he made available, for the first time, far more material about Sa’adeh than had previously been known. However, a reader of his book may still find it hard, within the welter of factual information, to gain a rounded impression of the saga. All is not lost, however. There is an abundance of information in the Lebanese press and memoirs of the Khoury era. And although press coverage of the saga was often tainted by political prejudice and personal animosity toward Sa’adeh or toward the government, several newspapers were able to provide a fair and generally impartial treatment of events as they happened. The most important wasan-Nahar, which kept its wide readership continuously informed and published almost daily disclosures and comments about the controversy. Personal memoirs and reports also contain valuable information and offer the reader various perspectives from participants and independent witnesses. Nonetheless, they should be handled with care as they illuminate only part of the picture and, because of their restricted scope, do so in a necessarily subjective manner.

Beyond the Arabic language, the saga is hardly known outside a narrow circle of academic specialists. There is no book in English – or in any other major European language for that matter – that attempts to give a concise, clear and authoritative survey of the controversy. There are chapters on certain aspects of the subject, on individual participants or on specific issues, but there is no one volume that provides a unified treatment of the saga with a view to helping the general intelligent English reader as well as the student to form a clear picture of causes and consequences. Even in the most direct studies on modern Lebanon, the Sa’adeh saga is treated by scholars mostly at a quite general level.

The existing secondary literature is even less helpful. In contrast to the rich literature on the general phenomenon of Lebanese political crashes, there are relatively few comprehensive historical studies of the Khoury era. It was not until recently that the drought was broken with the publication of Eyal Zisser’s major studyLebanon: The Challenge of Independence.10Zisser explains the dearth of literature on the “independence era” (ahd al-istiqlal) as follows:

The voluminous struggle over the valid interpretation of Lebanese history failed to elicit much interest in the events of 1943–52. Researchers inclining to a deterministic view thought of that decade as marginal and as devoid of influence on what was in any case destined to follow. For them, an understanding of Lebanon had to be anchored in an analysis of the emergence of Greater Lebanon, of the National Pact, of the 1958 crisis and, most of all, of the civil war. But their counterparts, too, did not find much to attract them to this particular period, at least not beyond the initial struggle for independence and the formulation of the National Pact. Most scholarly histories of either school therefore devote no more than a few lines to the entire decade.11

Zisser’s book has a chapter on the Sa’adeh saga but it doesn’t go far enough. Other attempts are no better.12Most are ill-informed, full of factual errors, narrow in scope, bizarre in their organization and emphasis, and generally lacking in enthusiasm. Some can be followed only by Lebanese specialists, while others are far too general and brief to satisfy the needs of the reader who wishes to acquire an adequate knowledge of the subject.

The task here is to portray and explain the puzzling complexity of a political trial that went very wrong. Critical to this task is anunderstanding of the confusing and muddy borderland where politics, criminality, and law often overlap. However, the reader must be alerted as to what this volume is and is not. It is a multidisciplinary exploration of the historical and theoretical underpinnings of a political saga involving variables in politics and law and societal responses to it. It is not a comprehensive historical work or a legal treatise; although some events and law matters are examined in depth, most are referred to, if at all, at a quite general level. Generally, this volume is less a history of a trial than it is a dramatic representation of a tragic episode.

Structurally,Outright Assassinationfalls into three general sections. The first section is an exploration of Sa’adeh’s political discourse and attitude towards the power structure in Lebanon. It covers his turbulent relationship with the Lebanese State from its origin in 1936 to the period immediately preceding the trial. It would be futile to attempt to explain the controversy without a lucid understanding of Lebanese state politics and Sa’adeh’s reaction to it. The controversy was ideological as much as it was political, and not a straight-forward treason case as it has often been made out to be.

The second section is an attempt to unravel without interruption the last threads of the plot against Sa’adeh’s life. It is a step by step reconstruction of the trial and execution, with its slow and measured procedure, based largely on press reports, published testimonies, and personal recollections of those who lived in that period. In the absence of court records, it is very difficult to confirm the accuracy of the information, but there does seem to be strong consistency between the various accounts. From this re-enactment, the discussion proceeds to an analytical review of the trial process under national and international law.

The third section provides a round-up of the myriad reactions generated by the case both inside and outside Lebanon. The intention here is not to record every detail of the Sa’adeh affair, but to touch instead on the salient aspects, and thus both pave the way for further studies on these topics and to provide a backdrop for those generally in need of dependable information. After that is an enumeration of the various assumptions and theories that have developed about the case in an effort to determine to what extent they differ from one another and why these differences occur. Generally, we will be concerned with developing an inventory of how far these theories have brought us to an understanding of the saga. The section will conclude with asurvey of the fallouts from the saga and its repercussions on the main parties.

The present book originated in the need to discover answers. This attempt is made in the full knowledge that, for the foreseeable future, it will not be possible to explain the “why”, “who” and “when” of the Sa’adeh saga more accurately until the secret archives of the Lebanese security services and military court, where Sa’adeh was tried and executed, are opened for public scrutiny. Until then we have to rest content with the available information.

.

Notes

1 It is claimed that Husni az-Zaim watched proceedings from behind the door but refused to make an appearance. Another claim is that Sa’adeh threw back at him the pistol that Zaim had earlier presented as a token of friendship. Neither claim can be confirmed. See Adib Kaddoura, Haqa’iq wa Mawaqif(Facts and Stances). Beirut: Dar Fikr, 1989.

2An-Nahar, Beirut, 9 June, 1949. See also Nada Raad, “Tueini talks about his turbulent relationship with SSNP: death of party founder Saade seen as turning point.” Beirut:Daily Star, Saturday, 22 May, 2004.

3 Ibid.

4Fikr. Beirut, No. 73, 1 July, 2000: 76.

5 For an introduction on this relationship see Adel Beshara,Lebanon, The Politics of Frustration: The Failed Coup of 1961(History and Society in the Islamic World). London and New York: Routledge and Curzon, 2005.

6On Sa’adeh’s life and thought see Adel Beshara,Syrian Nationalism: An Inquiry into the Political Thought of Antun Sa’adeh. Beirut: Bissan Publications, 1995;Antun Sa’adeh: The Man, His Thought. London: Ithaca Press, 2007.

7 Ron Christenson,Political Trials: Gordian Knots in the Law. 2nd ed. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Press, 1999.

8 Otto Kirchheimer,Political Justice. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1961.

9 Antoine Butrus,Qissat muhakamat Antun Sa’adeh was i’idamehe(An Account of Antun Sa’adeh’s Trial and Execution). Beirut: Chemaly & Chemaly, 2002.

10 Eyal Zisser,Lebanon: The Challenge of Independence. London: I. B. Tauris, 2000: 176–192.

11Ibid., xi.

12See the chapter on Lebanon in George M. Haddad,Revolution and Military Rule in the Middle East. 3 Vols. New York: Robert Speller and Sons, Publishers, 1971; Chapter eight in Patrick Seale,The Struggle for Syria: A Study of Post-War Diplomacy 1945–1958. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965.

.

1 ESSENTIAL BACKGROUND

Antun Sa’adeh has the dubious distinction of being the first and last political figure to be executed in independent Lebanon. A committed ideologue, Sa’adeh was positioned to the left of mainstream Lebanese politics and the confessional system, which he considered too impractical and slow to forge an independent national life.1His life was tinged by a spirit of rebellion, which led him to scorn all half-measures and vacillation and which influenced the intransigence with which he later stuck to his program of national revival. But “rebel” he was, and as rebel, we may be sure he paid the price that always goes with such independence of thought and action.

Admired for the broadness of his intellectual sweep, his single-minded concentration on the national cause, and his commitment to rational principles, Sa’adeh was destined for a personal tragedy. But no one, including his political detractors, envisaged that it would be through the death penalty. Many expected him to die in cold blood or to live the rest of his life on the run or in exile, but not to be executed behind closed doors in Star Chamber style.2Many more expected the State, in the longer run, to triumph against him but they never imagined that it would be without any physical or moral restraint. This was an intolerable breach of faith.

In order to understand how Sa’adeh came into circumstances that cost him his life, it is necessary to recreate the “rebel” before our eyes, placing ourselves, as far as possible, in his intellectual environment, and to touch upon the salient features of his relationship with the Lebanese State. During the last half-century this relationship has been normally discussed – or more often simply alluded to – primarily within the context of the political development of Lebanon. Because of this, the existing secondary accounts are strikingly inconsistent in the information they provide. They have given rise to an amazing variety of conflictingtheories and evaluations. Here, however, we study the relationship as an internal affair involving complex relations among all the players who participated directly or indirectly in it. We explore its evolution phase by phase, and the central issues at question are taken as a whole and considered within a wider context than that of traditional scholarly interest in modern Lebanon.

Lebanon: The Long March to Statehood

At different periods in its history, Lebanon or Mount Lebanon before 1920, a mighty range which begins northeast of Tripoli and extends approximately to a region east of Sidon and Tyre in the south, has held an important position as a shelter for minority and persecuted groups, including its historic Maronite Christian majority, the monotheistic Druze, and local Shi’a Muslims. Other sects that are known to have settled in the Lebanon region are: Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholics, Jacobites, Syrian Catholics, Chaldean Catholics, Nestorian Assyrians, Latins (Roman Catholics), Protestants, Sunni Muslims and Jews. These sects co-existed, often with antagonistic interests, but could not mold into a unity of any measurable degree. Like “outright castes,”3each sect managed its own internal affairs and personal status laws independent of the other sects.

In the mid-1800s, as nationalism penetrated the Syrian environment, this arrangement came under close scrutiny. Functionally, nationalism and sectarianism are opposites: nationalism is a collective spirit in which the relationship of the members of a nation is, theoretically, an equal relationship between citizens; sectarianism, on the other hand, refers (usually pejoratively) to a rigid adherence to a particular sect or party or religious denomination. It often implies discrimination, denunciation, or violence against those outside the sect. Moreover, as exclusive communities, sects “defy the environment in which they grow”4and their members tend to possess a strong sense of identity that limits “one’s contact with others and the kind of occupation that was open to the individual.”5

With the advent of nationalism, Mount Lebanon found itself at a new crossroad in history. It became the stage for a major literary revival spearheaded by a small but active intellectual stratum willing to question the existing order of things. And so, amidst the pervasiveness ofa sectarian mentality, various nationalist tendencies began to appear with fresh concepts and universal claims about how the region should be organized. Chief among them were:

A secular Syrianist tendency, which considered Mount Lebanon an indispensable part of Syria;A pan-Arab tendency, which emphasized a national union on the basis of a singular Arab identity; andA Lebanonist tendency, which portrayed events on and around Mount Lebanon within a distinctly Lebanese context.By the turn of the twentieth century those tendencies were clashing over whether Lebanon’s identity was to be considered from a pan-Arab (or pan-Syrian) or a narrower nationalist Lebanese perspective. Although Lebanese Christians were the first intellectuals to promote a sense of pan-Arab (or Syrian) identity, they grew alienated from the movement after pan-Arabist theoreticians, for whom the very concept of historical Lebanon was increasingly anathema, began holding sway. Many felt that Lebanon’s identity could only be understood within the context of greater Syria and eventually a larger pan-Arab framework. The dividing lines eventually coalesced roughly around sectarian groupings, hampered by a rigid and static stratification, and the national identity of Lebanon remained undecided.

On September 1, 1920, against a background of intense national confusion, the French High Commissioner in the Levant, General Henri Gouraud, surrounded by a hand-picked audience of local religious and political leaders, declared the birth of Grand Liban (Greater Lebanon).The new entity, in addition to the pre-war mutassarafiyyah (governorate), included new areas and towns that were inhabited by a majority of Sunni and Shi’a Muslims. It increased the Sunni Muslim population of the new state by eight times, the Shi’a Muslims by four times, and the Maronite Christians by only one-third of their original number in Mount Lebanon. The inclusion of such significant new population groups was deemed necessary for economic viability, but it brought with it serious problems. First, Greater Lebanon engulfed two areas unequal in their level of capitalist development and their access to services and resources: the more advanced area of Beirut and Mount Lebanon, constituting the center, and the less advanced areas of northern, eastern, and southern Lebanon, constituting the peripheries.6 Second, the new entity was created against the wishes of a significant number of its population. A large number of the center’s residents were Christians, and many of them, particularly Maronites, were advocates of the new state. A good number of the peripheries’ residents were Muslims, and many of them, in addition to a good number of Christians, leaned toward reunion with a Syrian/Arab nation. The different concentrations of sectarian communities in the center versus the peripheries also meant that Christians, predominantly of the center, had better access to resources while Muslims, predominantly of the peripheries, had less. This access also varied with class differences, with the upper classes of various religious affiliations in both regions having much better access to resources.7 Third, the inclusion of a substantial Muslim element undermined the new entity because the overall Maronite community slumped to about thirty per cent of the population. The French may have done that in order to weaken the Syrian Arab national movement in Syria and, simultaneously, to secure long-term Maronite dependency on them.

The initial main challenge for Greater Lebanon was to create a sphere for the two large religious groups and several other religious communities to live and function side by side. In 1926, a Lebanese Constitution was drafted under French supervision to pave the way for the Lebanese republic and its transformation toward a Western parliamentary democracy. Under the Constitution, all Lebanese were guaranteed the freedoms of speech, assembly, and association “within the limits established by law.” There were also provisions for freedom of conscience and the free exercise of all forms of worship, as long as the dignity of the several religions and the public order were not affected. A structure for the electoral system, legislative and executive institutions in addition to the juridical and bureaucratic structure, was also provided by the new constitution, but it was based on a confessional political representation that followed a ratio of 60% to 40% between Christians and Muslims.8 The purpose was to give Lebanon a political framework where the different confessional groups in an already polarized and sectarian society could coexist and follow a “national” consensus. However, many Muslims saw the Constitution as an expression of Lebanese independence and Christian and French colonial domination. In fact, Muslim representatives at the Constitution draft meetings made it clear that they were against the very idea of expanding thelimits of mostly Christian Mount Lebanon to create Greater Lebanon incorporating Muslim areas and insisted that the record show their reservations. On another level, the Constitution combined two contradictory facts: the implementation of a Western political system based on equality and universal suffrage was one wanted fact, while a deeply rooted sectarianism in both Lebanese political and social culture was another actual fact that counteracted the former goal.9

Another problem was this: By superimposing Lebanon’s confessional-style politics on a democratic agenda, the new constitution, with tacit French approval, enabled a limited group of Christian families in Mount Lebanon and Beirut and Shiite and Sunni feudal landowner families in the coastal cities to usurp power for themselves. Cooperation among these families took place only in terms of a common interest that strengthened their own positions and increased their wealth. No space was given in this structure for those politicians or groups who aimed to transform the country into a democratic, pluralistic and fair society. From time to time political parties did appear but they were basically thinly disguised political machines for a particular confession or, more often, a specificzaim(political leader). Lacking traits common to parties in most Western democracies, they had no ideology and no programs, and made little effort at transcending sectarian support. Moreover, the absence of real political parties, in the sense of constitutionally legitimate groups seeking office, led to a new form of political clientelism, based upon but by no means identical to the older feudal system. It reduced the political process to one of squabbles over patronage rights.10

As a result, Lebanon became again a centre-stage for old divisions and disagreements over national identity. Two distinctly “nationalist” camps formed: a Christian Maronite camp that advocated for an independent Greater Lebanon within its existing “historical and natural boundaries;” and a mainly Muslim pan-Syrian Arab camp calling for “either complete unification with Syria, or some sort of federal system respecting a ‘Lebanese particularism’.”11 Both camps put on an “ideological” show – the unionist tendency even organized a campaign of civil disobedience to promote its cause – but the rivalry soon fizzled out into political jockeying for power and prestige. As soon as “Muslim politicians had come to realize that, whereas they might be of first-rate importance in Lebanon, in a Greater Syria they would at best be second-rate next to political leaders from Damascus and Aleppo”12they sought a face-saving accommodation within the Lebanese system. Likewise, most Lebanese nationalists began to recognize the need for the nascent state to co-operate with its Muslim hinterland and began a process of national reconciliation that involved greater inclusion of Muslims into the political process. That process was suspended with the outbreak of World War II.

In September 1943, elections for a new chamber were held amidst domestic division over Lebanon’s “republican” identity. In the ensuing debate, the Lebanese nationalists portrayed themselves as against any foreign influence, be it French or Arab. While paying lip service to the need for friendly relations with neighboring states, they continued to stress the Phoenician (i.e., non-Arab) origins of the Lebanese. For their part, Lebanon’s Arab nationalists were careful not to push too hard for Arab union on the grounds that it could incite violence and thus provide the French with an excuse to perpetuate their occupation. Two months after the elections, a deal was struck between the contending parties to enable Lebanon to gain full independence. This would take the form of what would come to be called the National Pact (almithaq al-watani), an agreement between two prominent communal leaders, the Christian Beshara el-Khoury and the Sunni Riad el-Solh.

Under the National Pact, Christian leaders accepted that Lebanon was a “country with an Arab face” while Muslim leaders, who had abandoned the idea of union with Syria, agreed to recognize the existing borders of the newly independent state and relative, though diminished, Christian hegemony within them. The traditional division of labour between Lebanon’s various confessional groups was upheld with the presidency being reserved for a Maronite, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim and the speaker of the house a Shia Muslim. The ratio of deputies in parliament was to be six Christians to five Muslims. These arrangements were meant to be provisional and to be discarded once Lebanon moved away from confessionalism. The Pact did not specify how and when this would happen. Matters were made worse by the fact that the agreement was never officially written down and the meeting between the two men was more or less a private affair. What the two sides actually committed to would be the subject of bitter disagreement for years to come. According to el-Khoury, as recounted in his memoirs, the agreement was a push for complete independence. The Maronite community would not appeal to the West for protection while Lebanon’s Arabists would not push for a federation with the East. However, whereas el-Khoury saw independence from France as the end game, el-Solh saw it as a prerequisite step towards a pan-Arab union. For el-Solh, the pact meant that the Arabists would agree to the legitimacy of Grand Liban and would pursue their objectives for Arab union through democratic means. Both sides agreed that independence meant self-determination; it was the manner in which that independence would translate into concrete policy that would become problematic.13

The Independence Era

Following independence on 23 November, 1943, it seemed that the National Pact had established Lebanon on acceptably stable foundations. The Lebanese political system displayed a modicum of unity and was successful in providing a basis for considerable freedom and prosperity. That it could do so depended upon it being asked to do very little. Whereas other parts of the Near East witnessed an expansion of government activity and, in some case, praetorian intervention, during the same period in Lebanon the government remained modest and civil. The Lebanese economy ran with a minimum of government control and with considerable success. Socially, Lebanon seemed to be heading in the right direction following the religious solidarity displayed during its charge for independence. Back then, in a first for Lebanon, the Maronite Archbishop and the Grand Mufti of Lebanon took a united stand against the French. A dispatch to theNew York Herald Tribunestated on November 16, in the midst of the crisis: “For the first time in many years Moslems and Christians are united against the French.”14And further “The most interesting aspect of the present disturbances is that members of all religions and sects are united.”15

With Beshara el-Khoury and Riad el-Solh at the political helm, the Lebanese had strong reasons to celebrate. Beshara el-Khoury was an exceptionally gifted organizer and orator. He had been in the political game almost from the proclamation of Greater Lebanon in 1920, when he was appointed as secretary-general of the Lebanese government, and was widely respected and supported by Lebanon’s economic and cultural circles. Though a self-confessed supporter of Greater Lebanon, el-Khoury displayed remarkable flexibility in politics and understood Lebanon’s unique social blend far better than his nearest rival, Emile Edde. He rose to the highest office in the state by forging closer relations with the Muslim community or, more precisely, with the Sunni elite, and by publicly acknowledging Lebanon’s Arab character and regional reality. Riad el-Solh, on the other hand, was a prominent Syrian Arab nationalist and one-time member of the short-lived Syrian National Congress under King Feisal. An urban notable from a well-established Sunni family, Solh was twice banished from Lebanon, in 1920 and again in 1925, for resisting French rule. His forceful personality, political astuteness, and outspoken views were the main mark of his personality. Solh was widely respected within the Sunni Muslim community in both Lebanon and in Syria, but it was his involvement in the Lebanese national quest in 1943 that finally turned him into a national zaim, at least in the eyes of his followers.

Upon assuming the country’s leadership, both Khoury and Solh sought to portray themselves as state-builders. The tone of Solh’s first cabinet statement, on 7 October 1943, speaks volumes:

The Government which I have the honour of heading and which emanates from this Assembly, regards itself as the expression of the people’s will. It is answerable before the Lebanese people alone, and its policy will be inspired by the country’s higher interests. Emanating from the Lebanese people alone, we are for the people first and foremost. It is for the purpose of making this independence and national sovereignty a real and concrete fact that we have assumed the responsibility of power.16

In practical policy terms, the Solh statement contained a number of proposals and ideas aimed at strengthening the “country’s laws and public functions:”17

Revision of the national Constitution “in such a way as to make it harmonious with our conception of true independence.”Re-organization of the national administration to strengthen the constitutional regime.Reform of the Electoral Law.Conducting a new population census.Greater regional and Arab cooperation in foreign policy.However, the statement is best remembered for its reference to the sectarian problem in Lebanon:

One of the essential bases of reform is the suppression of sectarian considerations which are an obstacle to national progress. These have injured Lebanon’s reputation and weakened relations among the various elements of the Lebanese population. Furthermore, we realize that the sectarian principle has been exploited to the personal advantage of certain individuals, to the detriment of the nation’s interests. We are convinced that once the people are imbued with the national feeling under a regime of independence and popular administration, they will gladly agree to the abolition of the sectarian principle, which is an element of national weakness.

The day which will witness the end of the sectarian regime will be a blessed day of awakening. We shall strive to make that day as near as possible. It is only natural, however, that the realization of this objective should call for a few preparatory measures in every field. These measures will require the close cooperation of everyone, so that the realization of this important national reform may receive the full approval of all the citizens without exception.

What has been said of the sectarian principle applies also to the regional principle which, if carried out, would divide the country into several countries.18

This movement, however, never occurred; instead of its purported state-building purpose, the independence regime cemented the sectarian divide in the country and helped to aggravate rather than disentangle issues of conflict regarding the character of Lebanese polity. It also reinforced the sectarian system of government begun under the French Mandate by formalizing the confessional distribution of high-level posts in the government based on the 1932 census’ six-to-five ratio favoring Christians over Muslims. Viewed from this perspective,

The National Pact . . . consecrated the traditional ‘Lebanese way’, and thus incorporated the defects of the old order into the new. This blocked the emergence of an efficient and functional administration; worse, it inhibited the various components of the population in their incipient identification with the new state. In the short term, a fairly stable equilibrium was thus ensured, but this was only made possible by sacrificing the prospects of stability in the long run.19

Once the regime turned confessional all the precepts of strong and responsible government went amiss. The state became an arena for competing interests and parochial benefits overtook the national welfare.

Many earlier proposals for securing Christian-Muslim co-operation, based as they had been on the Sarrail model of individual equality in a secular state, were reduced by the regime to a singular approach which endeavored to secure co-operation on a strictly confessional basis. The outcome was unsalutory: sectarianism became even more entrenched; the principle of balancing, which created multiple power centers, frequently inhibited the political process; basic philosophical differences between the sects widened; and bickering among elites, not only between Christians and Muslims but also among sects within each religious group, spread like wildfire.

Also during this period, the political system ofzuamaclientelism was institutionalized and expanded. This impaired the efficiency of the central bureaucracy and fostered widespread communal disenchantment owing to the system’s basic discriminatory nature. Like sectarianism,zuamaismhindered the emergence of a sense of national as opposed to parochial loyalty and turned the state into an arena for petty squabbles and power contests. As a result, corruption and nepotism reached an intolerable level and a steady gap in access to resources opened up, polarizing Lebanese society even further:

Although Khoury had professed himself defender of the constitution during the French Mandate, after independence he revised it to secure another term in office. He portrayed himself as the president of all the Lebanese, but under his reign his family, relatives, and friends, and the Maronite community as a whole, strengthened their hold over the administration, the judicial system, the army, and the intelligence services. He perfected what may be defined as a method of “control and share” – integrating the feudal bourgeois elites of the Sunnis, Shi’is, and other communities into the political and economic systems in return for their support of the status quo. This may have provided Lebanon with a more stable political system, as those who benefited from it had a vested interest in maintaining it, but it led to widespread corruption.20

Both Khoury and Solh were culpable. The pair swept to power in 1943 with a great deal of public credit and a broad base of popular support but turned out to be anything but state leaders. The people gave them a clear mandate to lead Lebanon into a new age: instead, they exhibited none of the necessary leadership principles and ideals of good governance. They offered the country a clear political agenda, but carried to fruitiononly what was deemed to be beneficial to their own political survival: the Constitution remained basically unchanged; nothing was done to cleanse the national administration; no population census was undertaken; and the electoral law was reformed to suit their own political ambitions. Only in foreign policy can their regime claim some credit, but that was only because the regional and international challenges to Lebanon in those years were hardly problematical.

Lebanon under the Khoury-Solh regime returned to its old political habits. Old and new wounds remained unhealed and social grievances became more acute than at any time before. Some of those grievances were directed at the regime itself; others at the political system; and others still at the political status as a whole. The Lebanese split yet again on national identity: those who felt uncomfortable with Lebanon’s “Christian” character rejuvenated their call for pan-Arab unity; others felt that Lebanon was marching to a political tune which was too Arab and too Islamic for their liking:

This tradition [of Christian tolerance] – let it be stated very bluntly – is now in mortal danger. There are two movements at work in the Lebanon today. The first is that traditional spirit which we have just described and which is cherished by the great majority of the Lebanese population. The second movement may be quite accurately described as the invasion of the Lebanon by Pan-Arabism, as represented by the present Lebanese Government headed by the Prime Minister, Riad As-Solh, a Sunni Moslem from a minority group in the Lebanon, who for the last twenty-five years has worked – against the will of almost the entire Lebanese people – to include Lebanon in an Arab-Islamic union. As long as France with its traditional support of Lebanese Christianity held the Mandate over Lebanon and Syria, the pro-Moslem forces had no chance: Their opportunity came during the War, when with the active connivance of Major General Sir Edward Spears, representing Britain in the Levant, the French lost their hold over Lebanon and Syria. A pro-Moslem Government was then propelled into office in the first elections held in the unmandated Lebanon, and almost without the awareness of the great majority of the Lebanon, the country was swung into the orbit of Arab League policy.21

For clarity, it should be said that internal dissatisfaction under the independence regime was not entirely sectarian. On the contrary, the most serious and most articulate challenge to the State and to the regimecame from secular groups and secular individuals from various political persuasions. Chief among them was Antun Sa’adeh. He was, and had been from earlier times, the Knight in shinning armor in the secular crusade not only against the State but also against everything it represented.

Antun Sa’adeh: The National Discourse

Born in 1904 into a middle-class family with an intellectual background, Sa’adeh cast himself as a clear-thinking maverick willing to tell his people harsh truths. In the pursuit of this goal he exhibited great independence in thought and action and was principled and committed to one theoretical line all his life. His intolerance of inconsistency, his passion for scientific facts and his belief in deductive reasoning reflected an absolute faith in the omnipotence of reason.22Yet, he is often remembered mostly for his towering personality and charisma:

To most people who met him, friend and foe alike, the impression which Antun Sa’adeh left was that of a man of unusually strong character and striking personality. He possessed a great deal of will power and was extremely intelligent with a deep insight for politics. Though his formal schooling ended before he completed his high school education, he was widely read and highly cultured. Furthermore, he commanded the respect of many of those who met him and exhibited all the qualities and attributes of leadership.23

In addition to these personal and intellectual qualities, Sa’adeh possessed remarkable leadership and fighting qualities that he was to display over and again. Writing many years later about his special relationship with Sa’adeh, Hisham Sharabi noted, “When he said, ‘The blood that runs through our veins is owned by the nation and it must be produced whenever the nation demands it,’ he meant it, literally.”24

Sa’adeh belonged to a generation which cultivated the imagination more intensely and deliberately than its predecessors. However widely the majority of its members differed in character, aim, and historical environment, they resembled each other in one fundamental attribute: they criticised and condemned the existing condition of society. The problem is they disagreed about the effectiveness of the proposed means of improving that society, about the extent to which compromise with the existing status quo was morally or practically advisable, about thecharacter and value of specific social institutions, and consequently about the policy to be adopted with regards them.25 The problem, also, is that their disagreements were nationalistic in tone but sectarian in essence.26 Sa’adeh, however, came to be wholly out of sympathy with these attitudes. He believed that human history is governed by laws which cannot be altered by the mere intervention of groups actuated by this or that ideal. From this arises the first fundamental difference between Sa’adeh and his contemporaries: national and not sectarian interest should be the benchmark of political action. Yet Sa’adeh could not at any time be classified into any of the existing currents: certainly he was in no sense a Lebanese nationalist or a pan-Arab. He believed that the right framework for national activity was Syrian nationalism based upon but by no means identical with earlier nineteenth-century notions of it.27

To prove his point, Sa’adeh studied nationalism.28He appealed, at least in his own view, to reason and practical intelligence and insisted that all that the people needed, in order to know how to save themselves from the chaos in which they were involved, was to seek to understand their actual condition. Next, Sa’adeh attempted a powerful critique of established situations during which he took direct aim at the zuamas:

The greatest calamity befalling Syria [he wrote in 1925] is thezuamawho have none of the qualifications for leadership. They are men who, if the truth is to be said, lack all political, military or economic knowledge . . . and if they happened to discuss a substantial national problem, they do this like children.29

With this attitude, common to the vast majority of revolutionaries and reformers at all times, Sa’adeh came to espouse a radical view of change. The term he used for that is nahda, a notion of change not only in the institutions and power structure of society, but also in its ideological foundation, and the beliefs and myths that stem from it. In other words, the crucial issue for Sa’adeh was not to substitute one government for another, or to speed the forthcoming birth of a new system that society could produce in its present condition. Nor was it a question of giving society an additional impetus to speed up its progression towards the realization of goals to which it was clearly progressing. The issue for him was that of changing the whole life of a nation whose development had stopped long ago, and whose objectivepotential for movement in new directions had shrunk and dwindled away to almost nothing.30

Once again Sa’adeh inveighed against the status quo in his country arguing that its institutions were unsuitable to the task of national revival and that, therefore, an alternative arrangement was required for that purpose. He had in mind a highly disciplined political party operating outside of and, if necessary, in opposition to the existing structure. The Syrian National Party (later the SSNP),31which he secretly established in 1932, was consciously designed with that objective in mind. Sa’adeh then raised the political stakes by bravely exposing worrying trends about the state of thinking amongst his political opponents. His tone was furious and often brutal. His critique of religious and sectarian “nationalism” was particularly scathing. Sharp, lucid, mordant, realistic, and astonishingly modern in tone, it poured ridicule on what he considered to be naively personal and communal interpretations of nationalism. Sa’adeh also rejected the class-reductionist interpretation of Marxism by defining nationalism as a state of mind for all social forces in which the nation is a “stake” for the various classes.32

Behind his assault on the prevailing political doctrines stood more complex emotions connected with his own self-image as the redeemer of Lebanon. As early as 192133he had posed the question of whether Lebanon’s interest would be better served by preserving its independent entity or by absorbing it into a union with Syria. And as far back as then the answer was a foregone conclusion: Lebanon is an invaluable part of Syria, no different, certainly no less important, than the rest of the country. A separate Lebanon thus represented one of those demands that Sa’adeh was either reluctant to accept, or unable to fulfil. After the Syrian National Party was founded, he would again break ranks with the Christian Lebanese by denying the sovereign impenetrability of Lebanon’s frontiers. “It is clear,” he asserted, “that the Lebanese question can only be sectionally justified. The Lebanese question is not based on the existence of Lebanon as something independent, or on the existence of a separate Lebanese homeland, or even on an independent Lebanese history. Its only basis is religious party partisanship and theocracy.”34

Such pronouncements aroused feelings of atavistic insecurity among the Lebanonists, who felt that Lebanon had a special mission in life and that in order to fulfil this mission Lebanese political independence must be preserved at all costs. In 1936 a campaign was spearheaded by the Jesuit newspaper al-Bashir in coordination with Bkirki, the fortress of Lebanese Christian nationalism, to deter Sa’adeh from pursuing his political objectives. While portraying themselves as the true patriots and creative defenders of Lebanon, its architects sought to project Sa’adeh as a traitor who had not been adequately socialized to comprehend the moral principles and realities of the socio-political order. The campaign was relatively successful but did not in the least shake Sa’adeh’s belief in his own views. The SNP leader went into damage control explaining that neither Lebanon’s destruction nor its merger with Syria was part of his intention. Emphasizing the difference between Lebanon as a “political question” arising from a religious motive and Syria as a “national cause” he stated:

Our Social Nationalist ideology is a social thing and the Lebanese entity is a political thing and we do not confuse the two. If utility or political conditions required that the Lebanese entity needed to become an actual, physical entity, the question from this aspect remains a purely political one and there is no justification to turn it into a national issue. Because of this, those who consider the Social Nationalist Party a party that exists solely to demand Syrian unity err or misunderstand its cause. Those who try to panic the ultras among the Lebanese by saying that the party wants to annex Lebanon to Syria are deliberately making false propaganda.35

Later, Sa’adeh was able to point to numerous factual errors in the Lebanonist nationalist discourse. “If the [Lebanese] Christians refer back to their scripture, the Bible,” he asserted in reference to the Phoenician thesis, “they will find that it is defined as the Phoenicia of Syria, not the Phoenicia of Lebanon.”36Again, “The Maronites, they being part of the Syrian people that is centred in the interior of Syria, are Syriac rather than Phoenician in their original tongue and in culture and blood.”37With clever use of their deficient historical knowledge of Maronitism, Sa’adeh was, in fact, able to question the Lebanonist discourse as a whole. In several simply and beautifully written accounts, he laid bare the anxieties of Lebanese particularism in a world where impassioned nationalism had managed to flourish.38

Alongside his well-reasoned critiques of Lebanese particularism, on another front in 1936, Sa’adeh opened fire on the political establishment and showed that its world-view would lead to national suicide. His targets,again, were thezu’ama,39 who had worked their way back into the system and were presenting themselves as “national leaders”: