18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

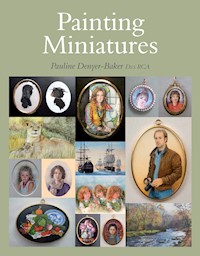

Miniatures are not simply small paintings: special techniques are used to achieve their unique glow and luminosity. This book explains how to paint in detail in a small format with colour and precision. It gives an introduction to the history and traditions of miniatures set by Holbein, Hilliard and Oliver. Advice is given on materials, paints, bases and framing and there are step-by-step demonstrations of stippling and hatching, watercolour and oil painting, and colour mixing. There is a focus also on portraits, still life and silhouettes. Drawing on her extensive experience, Pauline Denyer-Baker shares her passion for painting miniatures, and inspires both beginners and more experienced artists to master and enjoy this historic art form. With further advice on the importance of drawing and sketchbooks, and featuring work from leading artists with a range of styles and subjects, this is an inspirational guide aimed at all artists, particularly those interested in miniatures and portraits.Fully illustrated with 254 colour images.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 338

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

PaintingMiniatures

Pauline Denyer-Baker DES RCA

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2014 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Pauline Denyer Baker 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 841 7

Frontispiece: Lady with a Harp by Michael Pierce

Acknowledgement and Dedication

First of all I have to thank my son Rupert (who is also a portrait painter), without whose help I could not have organized this book on my computer, and my husband Brian for his design of the covers, his input on perspective, and his patience, as I worked slowly through it all. Also my eldest son Brendan for his patience too, and for explaining to my grandchildren how busy Grandma was!

I have written it for all the good friends I have made whilst teaching Miniature Painting, some of whom helped me on my way, and are no longer here.

Finally I dedicate this book to Molly Lefebure Gerrish, and her husband John, who encouraged Brian and myself as we pursued our artistic careers in the early days, and helped to make us succeed. Molly, who was a well known writer herself, would have been so pleased to know I had written this book, but they both missed the news by just a few weeks. I am indebted to them both for the inspiration they provided to me and my family.

CONTENTS

Introduction

1.

Miniatures explained

2.

A brief history of miniature painting

3.

Materials and workspace

4.

Subjects and sketchbooks

5.

Techniques and exercises

6.

Getting started

7.

Colour mixing

8.

Still life

9

Portraiture

10

Silhouette

11

Framing

Bibliography

Suppliers

Index

INTRODUCTION

It is commonly misunderstood that any painting is a miniature if it is small or very small; however, this is not true. A miniature work is quite different for several reasons. It is important to understand this, because if you really want to learn how to paint in miniature, it is probably surprising to find out how the techniques and methods of painting miniatures differ from the traditional methods of landscape, portrait and still life painting.

Societies of miniature painters do have certain rules and regulations, and broadly speaking, the subjects have to be ⅙ life size. This makes painting insects or small flowers and birds difficult, so most of these societies will look at the subject and, if painted in exquisite detail and with great care, they will accept these works for their exhibitions, as long as they adhere to the overall size of 6.5 inches × 4.5 inches including frame and mount.

Reduced photocopies of larger works may not be submitted, as each work has to be painted completely by hand. Small etchings are also allowed, but each one must be printed by the artist himself. This means that no one can churn out ‘miniatures’ quickly! But if like me, you love to paint in detail, in a small format, with colour and precision, then the miniature technique will appeal to you.

I put this collage of my work together, forty-two pieces in all, because I wanted to enter them for the RA summer exhibition 2006 called Rejects and – they were of course.

Although I had a formal Art School training, and learnt to draw and paint with various media and objects, I have always been fascinated by the fine details of the subjects I was trying to represent. I was taught life, costume life drawing, anatomy, classical architecture and studied paintings and the History of Art.

During the first two years I studied Fine Art (under the late Charles Knight RWS, who passed on so much of his knowledge to his students in an unselfish and enthusiastic manner), and this basic training was invaluable in my career as a designer and latterly as a portrait miniaturist. It was very important when I became a visiting art tutor at further education colleges in southeast England.

Eventually, but only after spending some more time studying portraiture, and miniatures in particular, I began to teach both of these disciplines to adults on leisure courses.

After having taught portraiture and miniature painting over the past twenty years I realized that there was a great need for a more comprehensive book on the techniques and all aspects of painting miniatures for the twenty-first century. It became an ambition of mine to write this book, in order to pass on some of the knowledge that was once given so generously to me.

Looking and perceiving

I was taught to perceive: not to just look, but to look twice and draw once! Please think hard about this concept, and make sure you understand the difference between looking and perceiving. Looking at a subject, such as a landscape, you appreciate it for its beauty, but if you are perceiving it, you are taking it into your brain, with the intention of painting or drawing the atmosphere, colour and life of what is before you.

This painting by Roz Peirson, who uses watercolour on paper, is of the Cornish coast at Zennor, for which she was awarded the Gold Bowl at the RMS exhibition in London 2012.

Drawing

It cannot be stressed too much how important it is to be able to draw, a skill that can be learned if the student is prepared to study and practise. Unfortunately, learning how to draw in the art schools these days is not a top priority, and because it has not been considered necessary for such a long time, it is probable that some of the tutors do not have the drawing skills to pass on the new students. Those students who succeed are those have a natural talent for drawing, or those who are prepared to work at it and study the basic principles of it such as anatomy, perspective architecture and landscape.

Sketchbooks

It is very important to keep a sketchbook in which to jot down ideas and make sketches regularly; it soon becomes second nature to try to get down the essentials of the subject. You will get used to looking carefully at your subjects (perceiving), in an effort to represent them accurately in your sketches, and ultimately in your artworks.

Especially where portraits are concerned, studies of faces, made in pencil or with colour, seem to help imprint the image in the mind, so that when it comes to getting a likeness, the brain is able to recall the personal characteristics. A sketchbook is also a place where you can make mistakes, and try things out, without any restrictions or criticism from outside influences. For learning portraiture, it is very useful to work from facial expressions in magazines, because the features are very clear. It is useful to keep them for reference, so that when you have to draw a particular expression in a portrait, you will have some something similar with which to compare your drawing.

A small selection of my sketchbooks, in which I work out my miniatures in advance beforehand, which I consider a vital part of the success of my paintings.

Reference files

It is useful to keep a scrapbook of ideas. If a pattern or shape or colour appeals, cut it out and keep it; it may well come in useful on a later project. Keep a box file for these, as your collection will grow as you become more observant. The patterns and shadows are usually exaggerated in photographs, but this makes you aware of them and helps you to understand how important shadows are in getting form and distance into your works.

Likenesses, colours and compositions

In order to learn about likenesses, colours and composition, it helps to look at books on art, studying in particular those artists who were expert in a particular subject. It is not necessary to look just at portrait miniatures; look at the work of all portrait painters, in various media. There is a lot to be learned by studying the works of those who have a broader approach, like Frans Hals, Vermeer, Winterhalter, John Singer Sargent, Gwen John, Allan Ramsay, Harold Nicholson – the list is endless. Although the miniature painting technique is so specific, one can learn a great deal about the form of the face, shadows and features from all artists who were portraitists. In fact you may well find certain techniques and shortcuts they made, which could also be applied to portraits in miniature.

Still life

For more inspiration there are all the artists who painted still life, such as William Nicholson and those who painted trompe l’oeil, such as Cornelius Gijsbrechts, a Flemish artist around 1670, who painted the most detailed and lifelike paintings of letter boards, pinned with all sorts of ephemera. My paintings of Pinboards, which include tiny portraits and silhouettes, were all inspired by these Gijsbrechts paintings.There was an exhibition of his paintings called ‘Painted Illusions’ at the National Gallery in 2000. If you look at his work, you will see how the details are so fine that they really do deceive the eye. One painting shows the back of a work, leaning against a wall, and it really tempts you to try and turn it over to see what is on the other side.

These trompe l’oeil miniatures, called Family Pinboards, were all painted directly from life, in watercolour and gouache. They were inspired by paintings by the artist Cornelius Gijsbrechts, whose paintings really did deceive the eye!

As they were painted in order to deceive the viewer, the detail is amazing. By observing these paintings, you can see how the artist worked out and simplified the details in paint, but was still able to represent them accurately.

Holbein

There is a parallel here with Holbein, who painted miniatures and portraits for the Tudor court. Before he came to England, Holbein was still painting portraits for the important clients in Flanders, and so that his clients would remember him on his return, he painted a fly on the cheek of a portrait, so that the sitter, in attempting to brush it aside, would be reminded how very good Holbein’s work could be, in case he returned. Holbein found favour with Henry Vlll, as he had hoped, and he became the official painter of portraits to the King, and the Tudor Court. However, it is said that Holbein had learned how to paint miniatures from Lucas Horenbout in Flanders.

Although the earliest miniatures were probably painted by Flemish artists such as Teerlinc and Horenbout (who worked upright at an easel, and wore spectacles even in those early times), the tradition of miniature painting became particular to England and artists through the years. The painting of Lucas Horenbout at his easel, as well as the works of the early miniaturists, can be seen in great detail in the book The Portrait Miniature in England by Katherine Coombs.

Holbein had no difficulty in applying his skills to portrait miniatures. One of which, a miniature of Mrs Small (previously called Mrs Pemberton), was said to be so fine that if Holbein had never painted anything else he would be famous for this miniature alone. Mrs Jane Small is set in a very unusual decorative frame, and can be seen at the V&A Museum in London (the frame is not original, and is believed to be of Spanish origin). The portrait was painted in gouache on vellum, stretched over a playing card, which can be seen clearly on the reverse. Holbein’s style influenced other artists when came to to the Court, and the art of portrait miniatures was embraced by more artists in England.

Some of the most beautiful and elaborate miniature portraits can be seen in the work of Nicholas Hilliard, who was also a silversmith, who made these frames for his miniatures. Hilliard also applied silver and tiny jewels to his portraits to make them look lavish, and also to illustrate the jewellery and pearls worn by Elizabeth l and the ladies of her court. He was followed by Isaac Oliver and his son Peter Oliver. The development of the art of the portrait miniature, and the artists through the centuries, follows in Chapter 2.

My sketches of the backs of paintings by Holbein, showing what he and his contemporaries used to reinforce the vellum they painted on, because it was the only card they had at that time.

CHAPTER 1

MINIATURES EXPLAINED

As stated previously, it is generally misunderstood that any small painting, in any medium, is a miniature. The word ‘miniature’ is in fact, derived from the word ‘minium’. This was the name for the red lead that was used to illuminate the capital letters in manuscripts, on vellum. These were usually written by monks, who were known as ‘scribes’, able to write at a time when many people could not.

Even monarchs were sometimes unable to sign their name on letters written by scribes, so a small circular portrait was painted in place of the signature, so that the person to whom the letter was addressed would recognize the sender. Eventually, these portraits were cut off and framed, and became keepsakes from loved ones, in the same way as we keep photographs of our families and friends. (They were not always a very good likeness, however.)

King Henry VIII commissioned Holbein, arguably the best portrait painter of the period, and an excellent miniaturist, to paint a miniature portrait of Anne of Cleves, whom Henry wished to marry. The portrait, which is now very famous, can be seen at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It is circular, as all miniatures were at that time, and framed in an unusual and beautifully carved white ivory round box. This was cut from a whole piece of ivory, so that the lid fitted perfectly, and the painting, protected by crystal, is the pleasant face of a young woman, Anne of Cleves. The King was taken by it and travelled to Flanders to meet his bride. Sadly, when he met her face to face, he was most disappointed, and unkindly called her ‘The Flanders Mare’!

These are examples of some old miniatures that I have collected. The two ladies are actually the same person, painted at different stages in her life. All are approximately 3 × 2.5in pained on ivory.

Holbein must have decided to paint her sympathetically, to please the King. A later miniaturist, Samuel Cooper, whose miniature portraits were more lifelike, was commissioned to paint Oliver Cromwell, who commanded that he should be painted exactly as he was, ‘warts and all’ – and this is where the saying comes from. Another saying comes from the history of miniature painting, a little later, when there was a fashion for painting the eye alone, very small, which was then framed in a locket or brooch. It would be given to the loved one to wear during their separation, and from this came the phrase, ‘keeping my eye on you’.

These are two of my small eye miniatures, from which come the phrase, ‘I have got my eye on you’, when the loved ones were parted. The smaller of these, my own eye, drawn from life and surrounded by a strand of hair, was exhibited at the RA Summer Exhibition 1993. The other is a copy of an original eye painting. Both are about 1 inch in diameter, painted on ivorine in watercolour.

So it can be understood why miniatures were always small, sometimes extremely so, and in the earliest times they were nearly always portraits. These were circular, and cut from the vellum manuscripts. As the genre developed the circle format became elongated into an oval, which also changed in shape as different artists moved on to other sizes. Later miniature works were slightly larger, but still a maximum of 8 × 10 inches, and painted using the same technique as portraits. They were called ‘cabinet miniatures’, simply because they were not carried on the person, like the eye, but put on display in rooms called ‘cabinets’, where they could be viewed in special cases. It is believed that this is the derivation of the word Cabinet, used in modern Government.

This larger painting, using the miniature technique of stippling and hatching, is a so-called Cabinet Miniature, which is showing the signs of wear and tear, due to its age.

Supports used by early miniaturists

Vellum

By far the most important reason for miniatures being singled out as special and different from traditional painting, was not the size, but the support upon which they were painted. Holbein and Hilliard would paint on card, and, as suggested earlier it was usually a playing card. This was then covered with a skin, which sometimes came from a chicken, but the finest of all came from an aborted calf, where the skin was smooth and fine, and unblemished by hair growth. Whichever type of skin was used, it was stretched over a circle or oval cut out of the card, and held in place by a type of gesso paste laid evenly on the top. This was called a ‘carnation’, and was burnished when it dried, which made the surface very smooth. The artist would have several of these prepared and coloured in various skin tones which were then matched to the sitter’s colouring. Nowadays we call this type of skin Kelmscott vellum, which is usually goat or calf skin (not aborted) filled with gesso, and smoothed and polished, which makes a really lovely surface to paint on. The gesso was made from plaster of Paris; today there are different types, but they are usually made from acrylic media, as they dry quickly. (Kelmscott takes its name from the area it is made, in Oxford, and it is where the artist and designer William Morris lived.)

Ivory

It was not until the eighteenth century that miniatures were painted on ivory. An Italian lady miniaturist named Rosalba Carreira, from Venice, first used it, and so it is to her that its discovery is attributed. It quickly became the most popular support for miniaturists to use. Portrait miniaturists liked the translucency it gave to the portraits painted on it. A very thin sliver would be cut from the elephant tusk, which was polished until it was very smooth, to remove any natural grooves from the surface. This made the ivory highly resistant to the watercolour paint applied to it, and so a special technique was devised to make the paint stay in place, called stippling, or hatching.

Miniaturists copied these techniques used by etchers, who were often craftsmen as well as artists. The most notable were Dürer and Rembrandt, who drew straight on to metal plates, which had been cut to the desired size of the work. Historically these plates were usually made of copper, but contemporary etchers use zinc, as copper nowadays is very expensive. Nevertheless, even today copper is still the preference of most skilled modern etchers.

Etching

The etching process is begun by the artist transferring a specially prepared, carefully drawn and researched image, directly on to the surface of the metal plate. To do this they use a fine stylus or even a needle. This is also called engraving, and for etching, it is always done by hand.

A proof of an etching, hand printed and coloured with ink, by Brian Denyer Baker, to show the strokes, hatches and stipples which are made on the plate by the tools illustrated. This technique builds up tone and texture, and was used by the earliest miniature painters.

The artists have to be very skilled in their draughtsmanship, because any mistakes made on the plate are impossible to correct; the drawing has to be absolutely accurate, not only in composition, but in tone as well. A lot of preparatory sketches of the shapes of objects, patterns and the different areas of tone are made. This is the reference the artist has to follow as he transfers the composition directly on to the plate.

The lightest parts of the plates are then sealed with a barrier of soot or wax, to protect the metal underneath it, so that when the plate is immersed in acid, the unsealed parts are eaten away by the acid. This is done several times, before printing, to achieve all of the different tones and textures which make up the etching.

In order to create these forms, shadows and tones, the etcher uses a special technique with his stylus, making tiny strokes or lines (‘hatching’), and tiny dots (‘stippling’). In areas of shadow, the strokes are cross-hatched, to create depth of tone. The dots are close and dense, or well spaced, to create areas of light or dark.

The zinc plates used for printing etchings show more clearly how the etcher has to draw his subject matter in fine detail, using different strokes, like stipples and hatches, with the stylus or needle. It has to be worked on in reverse, so all readable parts will print the correct way round.

It is all worked up very gradually until the desired overall effect is achieved to the satisfaction of the artist. Several prints are made, or proofs (so called because they can still be altered), by inking up the plate, with the ink worked onto a special gelatine roller, then rolled very evenly on to the metal. The plate is placed, ink side down, on a sheet of damp paper, on the flat bed of an etching press. The heavy rollers on the press are run over the plate (which is covered by a special woollen blanket, to soften and even out the pressing) by winding a handle, forcing the ink and the drawing into the paper.

When inked up by hand using a method called ‘a la poupeé’ (described in Chapter 5), the plate is laid on the bed of a press like the one shown here, ink side down on a sheet of damp paper protected by a blanket. Then rollers are passed across it by winding the handle through the press so that the ink is forced into the paper, and a print is made. Each one is printed separately.

This process is repeated several times, on new sheets of paper, until the printmaker is satisfied with the result. These initial proofs ‘artist’s proofs’, which are often different from the finished work, are unique. When satisfied with the print, at the final stage the artist will sometimes hand colour parts of the plate with coloured inks, using the poupée (see Chapter 5). In this way some of the prints (of which only a limited number are made) are different from the prints that are printed in a monotone. These are quite sought after by collectors. The metal plates can only be used for a limited number of etchings, as they wear out eventually, and have to be destroyed. Each limited edition print is signed and numbered by the artist, which are sold both framed and unframed.

Painting miniatures

The miniaturists copied from the etchers the techniques of stippling and hatching, but instead of a needle they used a loaded paintbrush, like a pen or pencil, to paint the portrait, and build up the colours in layers, separately, by putting one colour alongside another – thus mixing the colours in the eye, rather than on the palette.

In the dark areas, the colour has to be built up in many pale layers. Each layer has to be pale and dry; if the layers are too wet they mix together, instead of remaining separate, and the luminous effect will be lost. The technique ensures that the paint stays on the non-absorbent surface. If dark colours are painted on too wet and thickly in watercolour, they can flake off when dry.

This method of working is the key difference between miniature painters and artists who paint larger works of art. In order to make sure the darker layers of paint are applied evenly, it is best to finish the whole area with one colour before changing to another. An almost foolproof method, which I have worked out, is to hatch with one colour, and then cross-hatch with the same, all over the dark area. Let it dry, and then stipple the second colour in the holes of the trellis-like pattern between the cross-hatched strokes. This creates an even key, so the paint cannot flake off, because it has been applied with several layers.

Polymin and ivorine (see Chapter 3) have an eggshell-like, non-absorbent surface, but if the artist is using Kelmscott vellum, the watercolour can be painted in darker layers (and fewer of them) to get the deepest areas of colour, still making sure the paint is not too wet. Because the gesso on the skin is absorbent, in spite of being smooth it will come off on the brush if the paint is too wet. Works painted on vellum are sharper because of this absorbency, but the paintings lack some of the translucency of polymin or ivory.

Georges Seurat, the French Impressionist, painted with the stippling technique, but on a much larger scale of course. It was called pointillism; the effect was achieved by putting blue oil paint dots next to yellow, for example, and so creating the green of grass. However, when this technique is used on ivory substitutes, by painting tiny watercolour stipples and hatches on an almost transparent surface, a glow is created which is quite unique to miniature portraits.

Sadly, these days it is no longer possible to find authentically sourced ivory to paint on; due to concerns about animal cruelty and a rapid decline in elephant populations, it is not acceptable to paint on elephant ivory. Old ivory is therefore very scarce but painting on it is really satisfying, and the results are very beautiful. However, quite recently mammoth ivory has become available, sourced from Russia, where tusks have been buried for centuries in the frozen ground. It is quite fragile, and tends to craze and break up if cut by an amateur, which is probably the result of having been frozen for so long. It can be purchased ready-cut in standard sized ovals and rectangles. If it is handled carefully and framed securely, any work painted on it will last as long as any other support. Like ivory it is a lovely surface to paint on, and has all of the special qualities of elephant ivory.

If paint is applied too thickly when stippling, it will flake off when dry, as it has done on the is old miniature portrait. I have restored it, which takes a long time because the colours must match exactly.

The stippling and hatching technique, shown here on polymin (an ivory substitute, made from petro chemicals) in two colours only, light red and viridian, which are applied separately and not mixed together, so the colours mix in the eye of the observer.

Supports used by miniaturists today

Ivorine

Another product was used by modern miniaturists from the beginning of the twentieth century called ivorine, or xylonite. This was made from cotton fibres dissolved in nitric acid, called nitrocellulose. It was also transparent and was a very good substitute for ivory. Before the use of the by-products of petrochemicals (i.e. plastics like polymin) ivorine was used to make all sorts of household items, from combs and buckets to plant labels and latterly ping-pong balls.

Ivory, which is what most old miniatures are painted on, will crack if it is not kept carefully, because it curves back to the shape of the tusk. This miniature has a crack across the top right-hand corner, which I have repaired. Repairs have to be invisible!

Until fairly recent times it was still available for use, made and imported from Italy, and sold by miniature art suppliers. It cannot now be obtained in the UK, but it is still available in America. Ivorine will deteriorate if not stored carefully, and is particularly sensitive to light and heat (it is also highly flammable). It will warp and twist and eventually curl beyond use, if not stored away from ultra violet light, and wrapped carefully to prevent it from drying out. Ivory too, will warp and eventually crack, unless it is kept flat in a frame. It can be repaired if the break is flat, but it spoils the look of the painting unless it is repaired by a skilled restorer, and if the break is across the face within the portrait it devalues the painting quite considerably, in spite of the reputation of the artist who painted the work.

Polymin

All the information given in this book about painting on polymin also applies to ivorine. However, as with every support used by artists, from canvas and every other surface available, it must be stored carefully. No support is indestructible! Contemporary miniaturists prefer to use polymin or vellum, whilst some use smooth paper or special board. Recently a new paper called Yupo or sometimes Lana, has become available, which has a velvet-like surface, to which watercolour paint adheres readily. This will take thicker paint without flaking off so it is a good base upon which to paint silhouettes. So is Kelmscott vellum, but the best way to look after miniatures painted on any support is to make sure they are framed as soon as they are totally dry and complete, so the work is held securely in place.

This portrait, painted about 1900, has been damaged by condensation. If ivory, ivorine or any non-absorbent surface gets damp between the glass and the painting, the watercolour will get damaged, as shown on this example. The face, in this case however, is not affected.

Those painted on ivory substitutes should be protected with a wax coating before framing, and then they should always be hung in areas away from excessive heat, bright sunlight or damp conditions. The convex glass traditionally used to cover miniatures is to prevent any moisture that might form inside the glass from dropping onto the painted surface, and spoiling it. If condensation does form on the inside of the convex glass it will be able to roll down inside the curve of the glass, and away from the picture. In spite of this, damp can still cause damage to the work, if the moisture forms and reforms too much.

It is really down to common sense to care for precious paintings sensibly. Then they should last as long as any of the miniature works of Holbein, Hilliard, Cooper, Smart, Cosway and Engleheart have done.

Old miniatures

A great number of old portrait miniatures sold today are titled ‘portrait of an unknown gentleman’ (or ‘lady’), in the auction house catalogues. A piece of paper containing all this information, written by the artist, was placed between the painting and the back of the frame.

The artists did not sign the back of the painting as it would have shown through the ivory. Over time, the backs of the frames were taken off to find all the details about the work, and the information was very often lost for ever. Artists did sign their works, however, usually with a specially designed monogram, which was discreetly placed near the bottom of the picture.

To prevent damp and dust getting in and on to the painting, earlier miniatures were sealed to the backing paper by a special tape, much like the stamp hinges used by stamp collectors in the early twentieth century. It was dampened and bent over the two edges to make a dust and water tight seal.

If you take the time to study old portrait miniatures, and maybe copy one or two to learn about the technique, you will soon begin to recognize the style in which they were painted, as each artist had his own distinctive way of working. The portraits of Holbein for instance, were simply but beautifully drawn, delicately painted, and very lifelike; he only painted on vellum. The works of John Smart, in constrast, were always painted on ivory, and he had a distinctive way of painting the eyes of his subjects, which are always recognizable on his miniatures.

Later artists like Andrew Plimer, although very skilled, had a much more stylized technique; some other portrait miniaturist styles were very naïve, simple, and quaint. The portrait miniatures painted by Richard Cosway were painted in a more sketchy style, with very little colour on them, but he was able to get very good likenesses. His portrait of George IV is gives an insight into the king’s character and lifestyle.

Painting a miniature portrait, by Bill Mundy

Prior to painting the miniature I usually make a detailed sketch of the subject, together with a photographic session. Most people are not prepared to sit for over the 40–50 hours it takes me to paint a miniature portrait, so photographic reference becomes a very useful tool.

Having made a basic colour sketch of the sitter it is then reduced in size to fit the dimensions of the (normally oval) gold-plated frame. It is important to draw the portrait within the oval to ensure that it sits nicely, leaving enough space above the head, and incorporates a slightly larger amount of body when compared to the head length.

I then draw an exact outline of the painting with a 2H pencil on thin paper, which I cover the back of with soft (3B) graphite. This then is traced down onto the surface I will be using to paint the actual miniature. (My preferred surface is vellum, because of the stability and particularly in view of the fact that very sharp brushstrokes can be achieved on this material.)

After rubbing off the graphite I then, with the point of a size 00 best quality Kolinsky sable brush, lightly apply thin lines of watercolour – yellow ochre and vermilion for the face, and a variety of colours for the clothes. Quite often I commence the build-up of colours by painting the background or the clothes first. This sets the tone and depth of colour for the portrait, leaving the cream of the vellum untouched for the face. If I had started with the face it might have become too pale, and then it would have needed more colour and detail to balance properly.

Generally the colours I use for the face are Vermilion and Yellow Ochre with touches of Davy’s Gray for shadows, together with Violet and warm Sepia for darker areas. When painting hair it is best to follow the shape of the hair and to paint in small, free little lines, building up the colour as you go along. I never use white on my portraits with two exceptions: gouache white for the dots of light in the eyes, and for white hair if the sitter has a white beard or moustache. I never mix gum arabic with my colours (Winsor and Newton half-pans of best quality watercolour). To attain the ultimate detail – so important to obtain a good likeness – I work through a circular magnifying glass fitted with correct bright white lights. There is nothing worse than working under normal light only to find the following day when looking at the miniature in daylight that the colours are all wrong.

This painting of Dee Alexander by Bill Mundy, in watercolour on vellum approximately 3.5 × 3 inches, is a fine modern example of all the techniques described in this chapter.

Modern miniatures

Today, one often hears comments at exhibitions of modern miniatures, about the photo-realistic quality of some portrait miniatures – such as, ‘why not have a photograph?’ Of course it was not an option historically, and the painted portrait was the only way to have a portable likeness of a loved one. Nowadays this photo-realism is the norm, and has become the accepted modern way of painting miniatures. Many miniaturists who exhibit in society exhibitions are very skilled at this technique. But it does take a very long time to achieve, because the end product has to look flawless. There are some modern artists who stipple all the parts of the miniature, the background, clothing and any other objects included in the painting.

If you care to make a study of the techniques of historic miniature paintings in the Print Room of the Victoria and Albert Museum, you will find that only the smoothest areas are stippled. (If you do want to look more closely at miniatures in the Print Room, ring first to make an appointment, as it is not open every day.) However, the clothing and any scene depicted behind the sitter in the background are painted in the traditional way, and jewellery can be painted in an almost impressionistic manner. If looked at closely under a strong magnifier, the minimal use of strokes to depict these details is quite accomplished.

However, there is also considerable skill employed by the artist whose miniatures still look like paintings, not photographs. It is takes just as accomplished a miniaturist to get a likeness in the small format of a miniature, but still produce a painting. The artist has to capture that elusive core quality of the person coming alive for you as you look at the portrait. If you can achieve this it is a very satisfying experience, and you may be commissioned to paint miniature portraits, which is undeniably even more encouraging.

CHAPTER 2

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MINIATURE PAINTING

As we have seen in the previous chapter, miniatures in England and the rest of Europe were usually portraits that were painted in the place of a signature, and often cut out and kept as a treasured memento of a loved one. It is fascinating to discover, however, that far away in the East, especially in India and Iran, miniatures were being painted at about the same time as Holbein and others were doing so in England and other parts of Europe.

This ‘Decorative Miniature’ is painted on a porcelain plaque. These usually came from Europe, and were quite stylized and painted in a traditional way, but still quite small. This one of the Duchess de Parma has a lovely deep blue border with a gold pattern. This may have been made by a transfer, and was not necessarily painted by hand.

These eastern miniatures were allegorical and decorative and told stories of domestic scenes in exotic gardens, with animals, birds and flowers. Battles on land and at sea were painted very naively, but were amazingly small in size. The Moghul miniatures illustrated stories of love and courtship, some of which were erotic and intimate.

(More information on how to paint an Indian miniature, and how the students in India learned how to practise brush control, can be found later in this chapter. Instructions on how to make your own gessoed support are given in Chapter 5, and for burnishing and decorating with gold leaf – the art of verreéglomisé – see Chapter 10.)

A typical Indian painting of a love scene in a garden. Although it is about 5 × 9 inches, the figures of the couple are small, and the decorative border is very detailed. Although the Indian miniatures were usually painted on vellum, this one is painted in watercolour on paper, and the techniques used to paint it are not the stipple and hatch technique used in the west. The hairs on their brushes are curved, and the artists use very fluid strokes. They have to learn how to control these special brushes to make these curved shapes from a very early age, until it becomes second nature, which makes their miniatures so distinctive.

The earliest miniaturists all signed their works, with a special logo, usually comprised of their initials. These had to be very discreet, so they did not overpower the miniature. Several of the more famous ones are drawn here.