Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

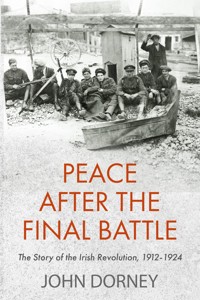

As we close out the decade of centenaries, and approach a re-appraisal of the Civil War our nation has never truly confronted, John Dorney's engaging history of those years – now in paperback for the first time – is a must read. Within the space of just a dozen years, Ireland was completely transformed. From being a superficially loyal part of the British Empire, it emerged as a self-governing state. How and why did Ireland go from welcoming royalty in 1912 to independence in 1922? In this exciting new updated edition, drawing on new research and the most recent material in this field, John Dorney, historian and editor of The Irish Story website, examines the roots of the revolution, using the experiences of the men and women of the time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 527

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PEACE AFTER THE FINAL BATTLE

PEACE

AFTER THE FINAL

BATTLE

THE STORY OF THEIRISH REVOLUTION 1912-1924

JOHN DORNEY

PEACE AFTER THE FINAL BATTLE

First published 2013

by New Island

2 Brookside

Dundrum Road

Dublin 14

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © John Dorney, 2014

John Dorney has asserted his moral rights.

PRINT ISBN: 978-1-84840-272-0

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84840-273-7

MOBI ISBN: 978-1-84840-274-4

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

‘The Irish attitude to England is, “War yesterday, war today, war tomorrow. Peace afterthe final battle.”’

Irish Freedom, Irish Republican Brotherhood newspaper, November 1910.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1: Before The Revolution

Chapter 2: Revolutionaries

Chapter 3: The Home Rule Crisis and the Birth of the Volunteers

Chapter 4: From Great War to Easter Rising

Chapter 5: The Easter Rising

Chapter 6: The Tipping Point, 1916-18

Chapter 7: The War for Independence

Chapter 8: Truce, Treaty and Border War

Chapter 9: Civil War

Chapter 10: Aftermath and Legacy

Conclusion: The Irish Revolution in Perspective

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Introduction

The germ of this book started some time back in the mid-2000s when I noticed a date on a memorial. The memorial was on Orwell Road in south Dublin, to one Frank Lawlor, and the date was 29 December 1922. As I was growing up, my father had often referred to this memorial and how the man it commemorated had died there fighting the British for Irish independence. When I was a child he used to call the spot ‘ambush corner’, and speculated that the IRA had chosen the site as it was on a tight bend, where a truck carrying British soldiers or Auxiliaries would have had to slow down.

The date, which I noticed purely by chance, immediately changed the story. December 1922 was well into the Irish Civil War, when Irish nationalists turned their guns on each other over whether to accept the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Looked at even more closely, the Irish language memorial gave up some more secrets. It read, ‘Francis O Labhlar, An Cead Ranga Comhlucht, An trear Cath, Briogaid Atha Cliath, d’Airm na Phoblachta, a dunmaruscaid ar an laithir seo’. (Frank Lawlor, 1st Company, 3rd Dublin Brigade of the Army of the Republic, was murdered on this spot.)

Not only was Frank Lawlor not killed fighting the British, he was not killed in combat at all, but ‘murdered’ by fellow Irishmen in the pay of the new Irish Free State. As it happens, Lawlor was picked up at his home in Ranelagh by undercover pro-Treaty soldiers or police and, apparently in revenge for the recent assassination of pro-Treaty politician Seamus Dwyer, was shot by the roadside, just outside the city boundaries. If my family had got the story of Frank Lawlor so wrong, I pondered, what did this mean for the story of the Irish struggle for independence as a whole?

This book is essentially an effort to ensure that the Frank Lawlors and what happened to them can be understood. The struggle for independence became the founding myth of the Irish state – a status that did nothing to encourage objective study. Such studies as there have been have all too often fallen into one of two traps. One was to glorify it, splitting the story up into various segments – the Easter Rising, the War of Independence and then, as quickly as possible, or perhaps not at all, the Civil War. In 1966, for instance, Roibeárd Ó Faracháin, in charge of marking the 1916 Rising on Irish state television, stated that‘While still seeking historical truth, the emphasis will be on homage, on salutation’.

The second trap was to use the upheaval of 1912–24 as a polemical way of arguing about contemporary issues – particularly the use of violence in the conflict in Northern Ireland that ground dismally on throughout the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s. To some extent in academic history, but especially in the media and in popular histories, the problem with these debates was that they were not primarily interested in the historical event at all, except as a way of either justifying political violence or condemning it, raging against the revolution betrayed in 1922 or giving thanks for the saving of Irish democracy, showing the illegitimacy of British rule or showing how a peaceful, liberal settlement of Irish grievances was foiled by irrational ultranationalists. None of which helped at all to explain how Frank Lawlor ended up dying on Orwell Road, shortly after the Christmas of 1922.

A great deal of the story of Ireland’s nationalist revolution remains basically untold. However, in recent years groundbreaking new research has opened up such topics as what guerrilla warfare really meant, how Northern Ireland became established and how the Irish Civil War was actually fought. This book is not chiefly a work of original primary research (though it does incorporate elements thereof), but a synthesis of the research of historians, Irish and otherwise, in recent decades. It has benefited hugely from the opening of archives such as the Bureau of Military History in 2003, which gives us an unprecedented view of events in those years. It hopes to take the reader though all of the events that led to the partition of Ireland and the substantial independence of two-thirds of the island in 1922. It is not principally a book about high politics, but rather about how the revolution was experienced by people on the ground.

At the same time, such a book cannot avoid engaging with some of the main arguments that have raged, and to some extent continue to rage, about the Irish revolution. The first of these was whether it was revolution at all. This book hopes to show that the struggle for Irish independence was indeed a popular mass movement, far beyond simply young men with guns; it incorporated those who marched against conscription, those who participated in general strikes, those who occupied land they believed belonged to ‘the people’ (or even themselves), those who campaigned for Sinn Féin (and against them), those who held torch-lit parades for returning prisoners. It will argue that social and economic factors, often dismissed as irrelevant to the nationalist struggle, were, unavoidably, at the heart of events as they progressed. In particular, the land question and its settlement punctuated the progress of the revolution at every step.

The British administration in Ireland before the First World War was not democratic as we would understand the term, nor was the limited autonomy known as Home Rule the same thing as Irish independence. Armed revolt was not inevitable – in large part it was a result of the frustrations caused by the First World War among Irish separatists – but nor was a militant challenge to the old order unforeseeable. While legitimate debates will continue as to whether violence was necessary to gain a significant measure of Irish independence, the argument that the upheaval of 1916–23 changed nothing is, this book will argue, false.

Another vexed question is to what extent the Irish revolution was a sectarian one, pitting Catholic against Protestant. This is a question that contemporaries never adequately answered, and here I have tried to show the complexities involved. Irish Republicanism itself was a specifically non-sectarian ideology, insisting that there was no difference between Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants. And yet Irish history and society meant that inevitably most separatists were Catholics, and that (not all, but a significant number of) Irish Protestants were ardent Unionists. At the same time, the creation of Northern Ireland saw openly sectarian violence between the Protestant majority, now with their own autonomous government, and the Catholic minority.

Finally, this book hopes to show that the Irish Civil War of 1922–23, often dealt with either on its own or as a tragic afterthought to the revolution, was in fact central to its conclusion and to its results. The disillusion and disappointment felt in the early years of Irish independence cannot be explained without a serious look at the intra-nationalist conflict, how it came about and how it was actually fought. It might have been that the partition of Ireland, which was mooted first in 1912, would have been confirmed in 1922 in any case. The independent Irish state might have emerged from the revolution conservative, hardened and suspicious of its own people. It might have been most concerned in its early years with avoiding bankruptcy rather than trying to tackle its social ills without the Civil War. But that it did emerge in this way was due in large part to the conflict of 1922–23.

It is hoped also that this book will show that the contemporary rhetoric of democratic pro-Treatyites against militaristic anti-Treatyites is a poor guide to explaining the chaos and muddle on both sides that characterised the outbreak of fighting over the Treaty.

Finally, this book tries to show how the participants, particularly the nationalist or Republican revolutionaries in organisations such as the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), saw themselves and what they were engaged in. The title of this book, ‘Peace After the Final Battle’, is taken from an article in the IRB newspaper Irish Freedom in 1910. From this perspective, the events of 1912 to 1924 represented a struggle between good and evil, ‘the final battle’ to right the wrongs of Irish history, to reverse the process of colonisation and to forge a new Irish nation. Whether they succeeded, and whether the effort was worth the cost, this book will leave readers to judge for themselves.

Chapter 1:

Before the Revolution

King George V of Great Britain and Ireland visited Dublin in July 1911. He attended horse races in nearby County Kildare and donated £1,000 to the poor of the city, before proceeding back through the southern thoroughfare of Dame Street to the royal yacht moored at Kingstown. The Irish Times reported that enthusiastic crowds had to be restrained by troops of the Irish Guards, while a band played ‘Come ye back to Erin’. The paper reported that ‘the cheering was sustained with enthusiasm and yet through it all there seemed an undertone of regret that a memorable visit, heartily appreciated by the citizens of every creed and class, had come to a close… “Long life to you” and “Come again soon” could be heard amidst the rounds of cheering’.1

Not everyone was so pleased to see the newly crowned monarch in Ireland, of course. The separatist newspaper Irish Freedom declared, under the headline ‘The English King and Irish Serfs’, ‘we owe him or his people or Empire no gratitude or hospitality’. He had been ‘guarded by spies and mercenaries and welcomed by helots [slaves]’.2 The Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) used batons on small knots of nationalist protesters at the visit.

Nevertheless, the dominant symbolism of the day was unequivocally that of the British establishment. Dublin was draped in Union flags, and crowds (though perhaps not quite of ‘every class and creed’, as The Times liked to imagine) did indeed cheer the king. Dublin Corporation, dominated by moderate nationalists of the Home Rule Party of John Redmond, boycotted the official reception, but the Lord Mayor did attend, while a committee of ‘Dublin Citizens’ issued a ‘loyal welcome’.

Twelve years later, on 11 August 1923, outside the new Irish Dáil or Parliament, green-uniformed Irish soldiers presided over another kind of pageant. They and another 2,000 guests (there by invitation only) saw the unveiling of a monument to two dead heroes, Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith. The President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, W. T. Cosgrave, paid tribute to them: ‘Scornful alike of glorification and obloquy, [they], following the path of duty, led forth their people from the land of bondage’.

They had, in other words, broken British rule over Ireland; a rule that had apparently been accepted and even welcomed by all but a minority in 1911. But Collins and Griffith died not in the struggle against the British, but in the fight against other Irish nationalists who would not accept the compromises they had made over the question of Irish independence. And according to Cosgrave, ‘the tragedy of the deaths of Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith lies in the blindness of the living who do not see, or who refuse to see the stupendous fact of liberation these men brought about’.3

Different countries

Ireland in 1911 was a very different place from Ireland in 1923. The years in between had witnessed a host of dramatic and often bloody events: the Home Rule crisis of 1912–14, the First World War, the Easter Rising of 1916, and intermittent guerrilla warfare across virtually the entire country during the period 1920–23.

In 1911 Ireland had been an integral part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. But by 1923 Ireland was divided into two new jurisdictions: the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland. The Free State covered two-thirds of the island and was effectively independent of Britain, though it was officially a dominion within the British Empire. Northern Ireland was an autonomous part of the United Kingdom. A new border divided the two, running in some cases through rural towns and villages. Partition constituted a major rupture in Irish society, but it was not the only significant change.

In 1912, Ireland was not a democracy by any twenty-first-century understanding of that term; only around 15 per cent of the adult population (and no women) had the vote.4 In 1923, both Irish states had universal adult suffrage. In the Free State, the police, Army and civil administrations of 1912 had largely been replaced by new institutions. The remnants of the old Anglo-Irish landowning elite, who had still constituted a sort of ruling class even as late as 1912, were now a small and powerless minority. Their remaining estates were in the process of being compulsorily purchased and subdivided. In the Free State they had been replaced as the ruling class, in political terms, by a new nationalist and predominantly Catholic political elite.

Even nationalist politics looked very different in 1923 from 1912. What the Home Rulers of 1912 had sought was an autonomous Irish Parliament within the United Kingdom. Some of them envisaged home government as Ireland taking its rightful place within the British Empire. On this basis, at the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, they enthusiastically encouraged their followers to enlist in the British Army. By 1923, a very different vision of what Irish independence meant had taken root. One that excoriated ‘imperialism’, and any connection at all with Britain, in pursuit of ‘the Republic’; an idea viewed as an impossibility, even an absurdity, by most nationalists in 1912. This ‘Republic’ was an ideal vague enough to mean almost anything in terms of what an independent Ireland would look like, but was concrete enough in the sense of rejecting all ties whatsoever with Britain.

So potent was this idea that Irish nationalists tore each other apart in 1922–23 over whether there could even be a temporary and symbolic acceptance of British sovereignty over a self-ruled Ireland – a distinction that would have seemed a ridiculous abstraction ten years earlier. In this decade in Ireland, therefore, there were dramatic shifts in the state, in politics, in power and in culture; enough, perhaps, to call this period of violent upheaval a revolution.

But there is another way to look at these events. For one thing, all of these processes – universal franchise, Irish self-government, land reform, the rise of a separate national identity buttressed by cultural nationalism – were happening anyway. In the end the British negotiated their withdrawal, securing, at least for the time being, their vital interests in Ireland before disengaging in 1922. For another, the period of 1912–23, though it did see the social and economic elite of Ireland challenged, did not in the end see it replaced or dispossessed. There was no social revolution. Indeed, both the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland emerged as rather socially conservative entities. By this reading, the armed struggle waged by Irish nationalists achieved not a revolution, but merely a speeding up of history, and got many more people (in the region of five thousand) killed in the process.

From these ambiguous results many different interpretations have been drawn. One, the mainstream nationalist one, states that Irish independence and national liberation, while not wholly achieved, were essentially secured by the struggle of 1919–21. According to taste, this can also be joined by the celebration of the securing of democracy against the most radical Republicans in the Civil War of 1922–23.

As against that, the Republican (and sometimes socialist) reading has it that the revolution was betrayed in 1922 – both by the acceptance of the partition of Ireland and by the crushing of political and social radicals in the Civil War that followed. A third, Unionist viewpoint sees the creation of Northern Ireland as a providential escape from ruinous Republican ‘terror’, and from the subsequent slide of southern Ireland into supposedly priest-ridden and economically backward stagnation.

Though it may show some strengths and weaknesses in the rival versions, this telling of ‘the Irish Revolution’ will not try to argue for any one of these interpretations. It hopes simply to tell its story.

The roots of conquest

If we are to judge whether Ireland experienced a revolution in these years, why it happened, how necessary it was and what it changed, we must look first at the ancien régime – Ireland under British rule.

Ireland had never been an independent unitary state. Before its partial conquest by Anglo-Norman barons in the late twelfth century, after which King Henry II of England claimed the title of Lord of Ireland, Ireland had been a patchwork of quarrelling Gaelic kingdoms. For around 250 years thereafter, the Irish and English lords had sometimes fought, sometimes allied with each other and rarely paid much attention to the small enclave around Dublin – named ‘the English Pale’ in the 1400s – that was governed by English law.

In 1541 Henry VIII, concerned about a rebellion of the Kildare dynasty and the possibility of Ireland being used by European powers to invade England, declared himself King of Ireland and embarked on a project to extend the power of his state over all of the island for the first time. It took the better part of a century of both fighting and negotiating to accomplish this. The resistance of both Gaelic and Old English lords (the latter the descendants of medieval colonists) was not quashed until 1603, and the process proved a bloody business. Indigenous Gaelic Irish culture, language and law were sidelined and replaced with English models. Large amounts of land were seized, most comprehensively in the northern province of Ulster, and granted to English, and later Scottish, settlers.

English authority also arrived with a new religion: the ‘reformed’, or Protestant, faith. The role of religious conflict in Ireland is complex, but by and large the population – both Gaelic and Old English – that had lived in Ireland before the Tudor conquest remained (or perhaps became, under the influence of the Counter-Reformation) Catholic – a status that both popular and elite accounts often confused with ‘Irish’. Like many early expressions of nationality, the Catholic Irish of the seventeenth century were an ethnic and linguistic mixture, defined largely by what they were not: Protestant, English, newcomers. It would be religion, not language or ethnicity, in the final analysis, that marked the boundaries of national identity in early modern Ireland – a fact that was still largely true by the early twentieth century.

It is not at all clear how well or how widely the doctrines of either the Catholic or Protestant religion were understood by the bulk of the population in seventeenth-century Ireland, but what is clear is that by the middle of that century most of the Irish population were, in their own understanding, committed Catholics. To what degree this was a straightforward response to colonisation and hostility to English rule is by now difficult to judge. Some, mostly Gaelic Irish people, certainly interpreted it in that way. Others, mostly Old English, maintained that they were loyal subjects of the Crown and merely wanted religious freedom. Nevertheless, the results of the religious split between Catholic and Protestant were momentous. For refusing to conform to the state religion, and for backing the pro-Catholic Stuart monarchs in two civil wars (1641–52 and 1689–91) the indigenous Irish upper classes lost virtually all their land and political power by the end of the seventeenth century, leaving both in the hands of a settler, mostly English, Protestant elite.

What this meant was that Ireland by the eighteenth century – though officially a kingdom in its own right, subject to the same king as England, Wales and Scotland (which after 1707 constituted Britain), but with its own parliament and laws – was in many respects a typical colony. The ruling elite was formed by a semi-closed group – foreign in religion, initially in language and in culture, from about 80 per cent of the population – the defence of whose position relied in the final instance on force from Britain itself. The Catholic religion and its adherents were excluded from landed, political and military power by a series of laws, known as the Penal Laws, which prevented them from holding public office, owning land valued over a certain amount and either voting for or serving in the Irish Parliament.

Conceivably, the Irish Parliament might have reformed itself into something more representative and autonomous had it lasted longer – indeed, it made attempts to do so towards the end of the eighteenth century, as well as softening legal discrimination against Catholics, who for instance received the right to vote in 1793. However, liberal Protestant reformism and Catholic discontent – which coalesced in the liberal Republican movement The Society of United Irishmen, founded in 1791 and inspired by the French Revolution – coincided with the Age of Revolution in Europe. The prospect of reform in Ireland ran into a wall of resistance fortified by the fears of more militant Protestants, or ‘Ultra-Protestant’ factions, and British fears of French invasion through Ireland. The subsequent repression of the United Irishmen led to their radicalisation and eventually to Republican insurrection in 1798 – the suppression of which convinced the London Government that rule of Ireland could no longer be left in Ireland. The Protestant elite, frightened by the rebellion and cajoled by bribery of various kinds, voted its Parliament in Dublin out of existence in 1800, and by the Act of Union of that year, Ireland became an integral part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Ireland under the Union

For the next century and a quarter, up to 1922, Ireland was governed at any one time by three administrators, only one of them elected and none of them Irish. The first was the Lord Lieutenant, the representative of the British monarchy in Ireland, who was usually an English aristocrat and who was based in the Viceregal Lodge in Dublin’s Phoenix Park. His position was increasingly symbolic, but like the king or queen he had the right delay laws for up to a year and to advise the executive branch of government.

Executive power lay in the hands of the Chief Secretary for Ireland, who was a Member of Parliament (MP) appointed by the incumbent government in Britain. Increasingly, the Chief Secretary took precedence in practical terms. When in 1905 a dispute arose between the Chief Secretary, Walter Long, and Lord Dudley the Lord Lieutenant, Prime Minister Arthur Balfour intervened, writing, ‘If you ask me whether in the case of differences in views the Chief Secretary should prevail, I can only answer yes. There can be but one head of the Irish Administration’.5 The Chief Secretary from 1907 to 1916 was Augustine Birrell.

The third prong of this trident was the Undersecretary for Ireland. This, unlike the Chief Secretary, was a permanent position held by a senior civil servant and based in Dublin Castle – the centre of English rule in Ireland for over 700 years and, in the minds of Irish nationalists, the dark Bastille of British rule in Ireland. The Undersecretary was responsible for the day-to-day running of the country. In 1912 the position was held by Sir James Brown Dougherty, who was succeeded by Matthew Nathan from 1914.

The personnel in the higher levels of the Irish administration were, moreover, almost all British and Protestant. The last Irish-born Chief Secretary was Chichester Samuel Parkinson-Fortescue, 2nd Baron Clermont and 1st Baron Carlingford (himself hardly representative of anyone beyond his own Anglo-Irish landed class), who had held the position from 1865–66, then again from 1868–71.

‘The Castle’ administration was disliked across the board among Irish nationalists, even the most moderate. For some of the more extreme: ‘Our country is run by a set of insolent officials, to whom we are nothing but a lot of people to be exploited and kept in subjection. The executive power rests on armed force that preys on the people with batons if they have the gall to say they do not like it’.6 A French observer living in Dublin thought the British regime in Ireland was underlain by deep-rooted prejudice that the Irish were simply not capable of governing their own affairs; what he called, ‘a gentle, quiet, well-meaning, established, unconscious, inborn contempt’.7

But in their own minds, most of the administrators of the Union in Ireland saw themselves as reformers, bringing good government and progress. This was particularly so in the case of Augustine Birrell and Matthew Nathan, liberals who saw their role as preparing Ireland gradually for self-government. So how had the British administration performed in its role as reformer of Irish ills, especially sectarian inequality and economic stasis, in the nineteenth century?

A century of reform?

Britain’s story in the nineteenth century was of industrialisation and gradual democratisation. In Ireland both of these processes – the creation of an industrial economy advancing political equality – were far from straightforward. Ireland began the nineteenth century not only with effectively a colonial administration, but with the great preponderance of political power and wealth held by Protestants. The roughly 800,000 members of the established Church of Ireland owned the vast bulk of the land. Of the 3,033 government jobs in Ireland, the Catholic population of perhaps six million held just 134.8

Order was still maintained by the largely Protestant landlords acting as magistrates and the largely Protestant Yeomanry militia carrying out their orders, which sometimes included the suppression of a state of low-level insurrection. When landlords attempted to raise rents during an economic slump after the Napoleonic Wars, it provoked an agrarian rebellion in Munster from 1821 to 1824 by the ‘Rockite’ movement (led by local figures in each district, who were each known as ‘Captain Rock’), in which over 200 people were killed and 600 ‘transported’ to Australia.9 Paying tithes to the Anglican Protestant Church of Ireland (the ‘established’ Church until 1869) was compulsory, and resistance to their collection led to another rural uprising, ‘the Tithe War’, from 1832 to 1834, in which the authorities recorded 242 murders in rural Ireland, along with 300 attempted murders and 568 cases of arson.10

Against this background, giving legal and political equality to Catholics in Ireland without disturbing the Protestant elite too much was a difficult task for London governments and one that advanced only in fits and starts. Penal legislation against Catholics (and some Protestants, such as Presbyterians) had been gradually repealed from the late eighteenth century onward, but it was not until a formidable mass mobilisation under Catholic lawyer and demagogic politician Daniel O’Connell that Catholics were granted full equality, with the right to hold public office being granted in 1829. However, to avoid Catholics having too large a majority in subsequent elections, in return for Catholic emancipation the electorate in Ireland was reduced sharply from 216,000 to 37,000 men as the property qualification for voting was raised from 40 shillings to £10 per year.11

Even after the 1850 Reform Act, which broadened the electorate to every man with property worth over £12, only one-sixth of adult Irishmen had the vote as opposed to one-third of Englishmen (women of course were excluded altogether until 1918). Voting also had to be conducted in public until 1872, meaning that a tenant who voted against his landlord could expect to feel the consequences. So it was not necessarily affection that ensured that landlords made up some 50–70 per cent of Irish MPs up to 1883.12

Nevertheless, despite the halting nature of progress towards political equality, by the end of the century Catholics did enjoy electoral dominance, where they were a majority. In 1840, when the Liberal Undersecretary for Ireland, Thomas Drummond, reformed Dublin Corporation so that it was elected on on the basis of property ownership (of over £10 per year) rather than religion, Catholic voters immediately outnumbered Protestants by over two to one. Daniel O’Connell became Lord Mayor of the city in 1841, the first Catholic to hold the position since 1689.13 Thereafter, until the 1860s, in order to avoid sectarian animosity, the office of Lord Mayor was alternated every term between Catholic and Protestant. After the 1880s, however, the city government became solidly nationalist – to such a degree that mostly Protestant Unionists in Dublin deserted the city centre and founded their own ‘townships’, such as Rathmines, outside the city boundaries. By the 1900s, Dublin, a city with a population of over 300,000 within municipal boundaries, had an electorate of 38,000, including some women.14

In 1898, the British extended the powers of local government in Ireland, effectively devolving local power to nationalist and Catholic representatives where they were a majority, meaning that Dublin Corporation in particular became a stronghold of constitutional nationalists, who viewed it as an Irish parliament-in-waiting.15

Rural County Cavan, located at the southern rim of the northern province of Ulster, provides a clear example of how the extension of the right to vote gradually undermined the political power of the old Anglo-Irish landed class. Prior to the expansion of the franchise in 1868, three landowning families (the Farnhams, the Saundersons and the Annesleys, all traditional Anglo-Irish landlord clans) controlled politics in the county, keeping its three seats in Westminster safe for the Conservative Party.

However, the introduction of the secret ballot in 1872 meant that they could no longer control how their tenants voted, immediately loosening their grip. The 1884 Act made Catholics (who made up 80 per cent of Cavan’s population) an electoral majority for the first time, and despite one Saunderson’s exhortation to local Orangemen to ‘drill, arm and don uniforms’ to resist Home Rule in 1886, political power in the county passed with little violence to nationalists.16 Still, despite being much more democratic at the close of the nineteenth century than at its start, by 1910 only about 15 per cent of the adult population of Ireland, or about 30 per cent of adult males, had the vote.17

Other features of Protestant domination were also gradually but slowly dismantled as the nineteenth century went on. In the 1820s, magistrates started to be appointed by central government rather than being automatically drawn from among the landlords in a given locality. In 1835 the Yeomanry militia was disbanded and disarmed, and power over law and order transferred completely to the new Irish Constabulary (which had been founded in 1822 and after 1867 was named the Royal Irish Constabulary, or RIC). The RIC alone among the police forces of the United Kingdom was armed, with carbines and revolvers, and was taught military drill.18

Moreover, unlike other police forces in the United Kingdom, it was responsible directly to the Irish executive, that is, the Chief Secretary for Ireland – and not, as in England, to locally elected representatives.19 Many Irish rural communities experienced violent confrontation with the forces of law and order in the formative years of the latter during the nineteenth century, especially during clashes between tenants and landlords (RIC officers were advised to ‘cultivate a friendly discourse’ with landlords).20 The novelist George Birmingham wrote in 1913, ‘In Ireland we are not supposed to love the law, it was made for us not by us. It is only desirable that we fear it’.21

In one respect, therefore, the RIC was as nationalists often complained: an example of colonial rule. But equally, unlike its predecessor the Yeomanry, the RIC was a law-bound organisation, responsible to central government – not the all-Protestant tool of the local landowner. By 1910, the great majority of RIC constables (81 per cent) were Catholics, as were 51 per cent of mid-ranking officers such as district inspectors. The ranks of senior RIC officers (often recruited from the military), however, remained dominated by British and Irish Protestants, who formed over 80 per cent of its top command.22

Though constables were still trained in firearms and military drill in 1912, by that time their carbines and revolvers were generally left in the barracks unless violence was specifically anticipated. The police, in short, were becoming more ‘civilian’ and more representative of the population they policed as the twentieth century dawned.

By that time, the state in Ireland was no longer officially Protestant. In 1869 the Church of Ireland was disestablished, meaning that other religions no longer had to pay tithes to it. The Catholic Church, after a long and drawn-out battle both with the state and with secular-minded Irishmen, was granted de facto control over the primary education of Catholics in the 1830s and its own university in the 1880s. Straightforward religious conflict was, however, still present in Irish society in the early twentieth century. In Dublin, for example, the Catholic Church and Protestant evangelical societies – notably the Irish Church Mission, founded in the early nineteenth century to convert Catholics to Protestantism – competed fiercely for converts in the inner-city slums23. Similar evangelisation battles took place in the remote west. In 1907 the Catholic Church decreed, in a bull known as Ne Temere, that all children of mixed marriages must be brought up as Catholics. In a highly publicised case in 1908, a Belfast Catholic, Alexander McCann, was pressurised by his local priest to take his two children away from his Presbyterian wife when she refused to convert.24

By 1910, a considerable number of Irish Catholics were quite integrated into British-ruled Ireland. Some 61 per cent of the 26,000 public employees in the civil service were Catholics and another 9,000 or so served as constables in the police.25 As many as 50,000 more served in the British armed forces or reserves at any one time. To take three prominent Republican fighters and memoirists of 1919–23; Ernie O’Malley’s father had worked in the Congested Districts Board, Tom Barry’s was a policeman and Michael O’Donovan’s (better known by his pen-name Frank O’Connor) was a soldier. Some future rebels recorded that in their youth they had been rather proud of the British Empire. Seán O’Faoláin, another policeman’s son who went on to be a Republican activist, wrote that on Sundays in Cork as a boy he would watch the church parade of the British regiments based there, and when ‘God Save the King’ was played, ‘I would whip off my cap, throw out my chest, glare and almost feel choked with emotion’.26

However, despite all the reforms of the preceding century, by the early twentieth century the economic, political and social elite in Ireland remained disproportionately Protestant or British or both. Todd Andrews, a youthful rebel in 1916, and later a senior Irish civil servant, recalled, ‘We Catholics varied socially among ourselves, but we all had a common bond, whatever our economic condition, of being second-class citizens’.27

Land

Aside from religious discrimination, the other legacy of colonial domination in Ireland was the land system, by which the landed class (not entirely Protestant, but dominated at the upper level by Anglo-Irish Protestants) owned very large estates and were paid rent by a largely, though again not solely, Catholic tenantry.

This too was undermined by reform from London and a series of Land Acts from 1870 to 1908. The first of these established that tenants could not be evicted without notice. Under the last, the 1903 Wyndham Act, and its extension in 1908, Irish tenants bought their land from their landlords with British Government loans, to be repaid over 70 years at 3 per cent interest. Nationalist and agrarian activist Michael Davitt heralded the results as ‘the fall of feudalism in Ireland’. Although the Land Purchase Acts depended on the landlord in question being willing to sell, the results were certainly dramatic. Whereas in 1870 97 per cent of land was owned by landlords and 50 per cent by just 750 families, in 1916 70 per cent of Irish farmers owned their own land. The Irish export trade in cattle and dairy products was also booming, and much of rural Ireland had never been better off. Incomes had increased every year since 1841 by an average of 1.6 per cent per annum, and agricultural wages had gone up 200 per cent.28 A Congested Districts Board supervised further land redistribution and, through improving farming methods and encouraging local industries, tried to relieve poverty in rural areas.

But like political reform, land reform in Ireland was granted only after bitter struggles. The 1820s and 1830s were marked by bouts of rural insurrection, and when the potato crop, on which the rural poor depended, failed due to blight in 1845, it triggered a catastrophic famine in which over one million died and another million fled the country. It has been debated to what degree the British Government was responsible for this disaster. According to Young Ireland revolutionary John Mitchel, ‘[A] million and a half of men, women and children, were carefully, prudently, and peacefully slain by the English government. They died of hunger in the midst of abundance, which their own hands created’.29 The nationalist charge that troops and police guarded food exports while people starved has been somewhat undermined by research that shows that British Government food aid was greater than food being exported.30

But the fact remained that direct British rule presided over a mass mortality famine in a country that was not at war, had not suffered a natural disaster such as flood or a drought, in which a functioning state was present and in which the means existed, through food aid from Britain, to feed all the people affected. Some £8 million was spent on famine relief, a figure which looks impressive until judged against the £69 million that the British Government spent on the Crimean War just five years later. In particular, the decision at the height of the famine to shift the burden of relief from government food aid to reliance on private charity undoubtedly cost many lives.

What left the greatest mark of all, however, was that – as tenant farmers could no longer pay rent, having sold everything to feed themselves – troops and police were used to evict some 70,000 families, or perhaps half a million people, from their homes, condemning many to death or destitution.31 Though mass emigration had already started from Ireland in the first half of the nineteenth century, the calamity of the 1840s turned a migration into an exodus. The Irish population in 1841 was approximately 8,200,000 people. By 1911 it stood at just 4,390,219.

In 1879, with an international slump in agricultural prices, there was again the prospect of mass evictions due to unpaid rent. That this did not happen on the scale of the Famine years was due to the formation of the Irish National Land League for tenant farmers, designed to prevent evictions and to negotiate collectively for ‘fair rents’. (Despite their efforts, though, as many as 30,000 families were still forcibly removed from their homes in three years). The Land League’s militant methods led to another bout of low-level conflict between Irish tenant farmers, the largely Anglo-Irish landed class and the state. From 1879 to 1882, some 12,000 agrarian ‘outrages’ – which could vary from burning hay to murders (about 60 of which took place) – were recorded.32 It was this agitation, known in Irish history as the ‘Land War’, that prompted the British programme of land reform in Ireland. As a result, most of its beneficiaries viewed the Land Acts not with gratitude, but as a partial reversal, won after a hard fight, of historic injustices. One Cavan IRA veteran, Seán Sheridan, remembered, ‘There always had been a void between the people and the RIC… The people had never forgotten the actions of the RIC during the Land League days’.33

The other problem with land reform – working on the premise that its goal was to pacify agrarian conflict – was that it did not actually change the structure of the Irish economy, which remained geared to the export of agricultural products to Britain itself. The large farmers who led the export trade (especially in cattle) and who availed of the Land Purchase Acts were simply freed from having to pay rents to landlords. Small farmers and agricultural labourers benefited little. In short, the Irish rural economy of the early twentieth century produced enough wealth, but not for enough people, and as a result emigration from rural areas remained high. The Irish Republican Brotherhood newspaper Irish Freedom complained in 1911, ‘Our land might be a garden for 20 million people, they [The British] have made of it a cattle ranch, supporting one-fifth of its rightful population’.34

The land question was not, as is often maintained, settled by the early twentieth century. It retained the potential for violent conflict. Famine was still not altogether a thing of the past in parts of Ireland, though government responses to it were now much better than they had been in the 1840s. There had been localised famines in, for instance, Kerry in 189835 and in Leitrim in 1908 – where local government had to supply emergency food aid to one thousand families to prevent starvation.36 Fear of famine, if not the absolute reality, remained a concern of Irish governments until the 1940s. At the turn of the twentieth century some 100,000 tenant families still lived on lands owned by traditional landlords, particularly in the west. Elsewhere it was cattle exporters, often the beneficiaries of the Land War, who tried to clear small famers off grazing land, leading to another bout of agrarian agitation known as the ‘Ranch War’ between 1906 and 1909. Conflict over who owned the soil of Ireland was still an issue. It would emerge again in the revolutionary period.

Industry

It is a truism of nineteenth-century Irish history that Ireland, with the exception of north-east Ulster, did not have an industrial revolution. Traditionally, nationalists blamed this on the British stifling of Irish trade by swamping it with cheap imports. Some northern Protestants attributed it to thrifty Protestant industry versus Catholic indolence. Others have pointed to the fact that most capital in southern Ireland in the early twentieth century was still in the hands of the Protestant upper class, that Irish banks all had their headquarters in London and that profits, largely made from agriculture, were rarely reinvested in Ireland itself. This, more than Catholic sloth, might explain the relative backwardness of much of the south of Ireland.37

Certainly though, Belfast (a city of nearly 400,000 at the turn of the century) fit the model of a British industrial city much better than Dublin did. The northern city had its shipbuilding and textile factories and row upon row of red-bricked terraced houses that surrounded them, giving homes to the working-class communities that sustained the industries. The fact that northern Unionists such as James Craig, the son of a distiller, felt that they had prospered under the Union, while southern nationalists felt their development had been stymied by it, contributed as much to the political divisions on the island over independence as did religion or ethnicity.

However, it is wholly misleading to see southern Ireland as a pre-industrial and unchanging backwater. Its main export – cattle – had to be brought to the ports and there loaded onto ships. Dublin manufactured Guinness beer and Jameson whiskey. The country was criss-crossed with railways by 1910, many owned by Unionist politician and railway magnate William Goulding. The south of Ireland was as capitalist as the north; the difference was that it was dominated by the export of agricultural products, especially cattle, rather than labour-intensive manufacturing products.

As was the case in public office and land ownership, the old Protestant elite still largely dominated the highest echelons of industry. But as in those other fields, this was slowly changing by the early twentieth century. William Martin Murphy – a farmer’s son from County Cork – became Ireland’s first high-profile Catholic and nationalist (he once held a seat for Dublin as a nationalist MP) millionaire. By 1910 he owned the Dublin United Tramway Company, giving him a near-monopoly on public transport in the city and a media empire that included newspapers such as the Irish Independent and Freeman’s Journal, and several other titles.

In the years leading up the First World War, Ireland, in common with many countries in Europe, saw the formation of modern trade unions by a new generation of socialist and labour activists (notably James Larkin and James Connolly) and experienced a wave of strikes. In 1907, a strike on the docks in Belfast briefly united Catholic and Protestant workers and even led to a strike among the police. In 1911, a nationwide strike on the railways was routed, with the owner of the Great Southern line, William Goulding, taking the opportunity to sack 10 per cent of the strikers as a lesson to the others.38

In 1913, Dublin was convulsed by a nine-month dispute known as ‘the Lockout’, which pitted some 20,000 workers against a cartel of Dublin employers led by William Martin Murphy, who ‘locked out’ their workers who refused to resign from Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU). The workers, after a bloody and bitter struggle, eventually caved in. There were also mini ‘lockouts’ in Wexford and Sligo in the pre-1914 years.

Such disputes heightened the confrontation between rulers and ruled in Ireland. The business elite were often Unionists, and the police and troops used to protect their interests wore the uniform of the Crown, but by themselves such strikes were not revolutionary. For one thing they were essentially disputes over non-revolutionary matters such as wages and union recognition. For another, moderate nationalists in the Irish Parliamentary Party generally also disapproved of militant trade unionism. Labour would play a role in the Irish revolution, but not the central one.The main driver of political conflict in Ireland was the question of Irish independence.

Freedom for Ireland?

If the majority of the Irish population was being gradually enfranchised and given a stake in the system of British rule in Ireland in the nineteenth century, the question arose, throughout the century: might not the majority actually govern the country? With the political system reformed, might Ireland not be granted the return of the Parliament that had been abolished in 1801, or failing that, some other form of self-government?

On this point, however, Irish aspirations consistently ran up against two immovable forces. One was the ‘Protestant interest’, as it was known – an alliance of the Anglo-Irish upper class and working-class Protestants (mainly, but not only in Ulster) – both of whom feared for their position in an Ireland run by the Catholic majority. The other was the imperial British Parliament, which throughout the century remained opposed to Irish self-government.

Daniel O’Connell, having mobilised the Catholic masses to achieve Catholic emancipation in 1829, tried in the 1840s to mobilise them again for the ‘Repeal of the Union’ – that is, the reconstitution of the old Irish Parliament. His campaign drew crowds hundreds of thousands strong, but fell apart in 1843 after a planned mass meeting in Clontarf in Dublin was banned by a government that said it would be ‘an attempt to overthrow the constitution of the British Empire as by law established’.39 Two regiments of troops and a warship were drafted in to make sure it did not go ahead. There were two insurrections by radical nationalist groups in the mid nineteenth century, one in 1848 and the other in 1867, with the goal not just of self-government but of the establishment of an independent Irish republic. Neither really got off the ground in military terms, but as social movements were much more significant than they are often given credit for.

The first, in 1848, was led by the Young Irelanders, a splinter group of both Protestant and Catholic intellectuals from O’Connell’s Repeal movement who disagreed with his conciliatory tactics. Coming during the Famine, it achieved little, but the Young Irelanders’ Irish Confederation had some 45,000 members across Ireland, and well-worked-out plans for rebellion.

The Fenians, or Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), founded in Paris in 1858 by refugees from the Young Ireland movement, also attempted an insurrection in 1867. As many as 8,000 men marched from Dublin out to Tallaght Hill in March of that year, as a prelude to a rising in the city itself, and several thousand more mustered in Cork, Limerick and Drogheda. But without a clear plan, and with much of their leadership already imprisoned, they dispersed after some isolated skirmishes. The British Government in Ireland suspended habeas corpus (the right not to be detained without evidence) for several years as a result of the Fenian threat. Three Fenians arrested for their part in killing a prison guard in Manchester were hanged – entering Irish nationalist legend as the ‘Manchester Martyrs’ – and over one hundred more were sentenced to death but reprieved after a popular campaign for amnesty.

Thereafter, most Irish nationalists reverted to the more moderate demand of ‘Home Rule’, or autonomy within the United Kingdom. In 1870, the Home Government Association was founded by a Protestant lawyer named Isaac Butt seeking a new Irish Parliament. By linking up with land agitation pioneered by former Fenians such as Michael Davitt, the association became a social movement and then a powerful political party under a liberal Protestant landlord named Charles Stewart Parnell in the 1880s.

Parnell’s party, the Irish Parliamentary Party (also known as the Home Rule Party, the IPP or simply the Irish Party or ‘the Party’), effectively monopolised politics in southern Ireland for the following fifty years. At Westminster it agitated for Home Rule, generally in alliance with the Liberal Party, while in Ireland itself it built up a formidable political base, based on the Catholic parish and in close collaboration with local priests.

In 1886 the first Home Rule Bill was drafted by William Gladstone but defeated in the British House of Commons, as ‘Liberal Imperialists’, loath to see the break-up of the Empire in any form, voted against their own party. Bloody rioting also broke out in Belfast, before and after the Westminster ballot, between Catholics and Protestants against the background of the vote, at a cost of about fifty lives. Northern Protestants had also been against Repeal in the 1840s, but it was in the 1880s that Ulster Unionism was born as a political movement, closely allied with the Conservative Party in Britain.

In 1891 Irish Party leader Charles Stewart Parnell became embroiled in a divorce scandal and was denounced by the Catholic hierarchy. The Party split acrimoniously between ‘Parnellites’ and ‘anti-Parnellites’ (or ‘clericalists’, due to their following the Catholic Church diktat in denouncing Parnell). Nevertheless, in 1893 a second Home Rule Bill came before the British Parliament and passed the House of Commons, but was defeated in the House of Lords. In 1900, the Irish Party reunited under the leadership of John Redmond and by 1912 it had again leveraged the Liberals into drafting a Home Rule Bill, the Third, and putting it once again before the House of Commons. This provoked muted celebrations among nationalists and furious opposition from Unionists, especially in the north-east.

Home Rule could not be confused with Irish independence, or even with O’Connell’s demand for ‘Repeal of the Union’, which would have reconstituted the Kingdom of Ireland as it existed prior to 1800. Home Rule envisaged the creation of an Irish Parliament, subsidiary to the one at Westminster. It would have no control over collecting taxes, over the police or military, over foreign relations or even over the postal service. The final realisation of dreams of Irish freedom it was not.

There the question of Irish self-government stood on the eve of the First World War. Home Rule appeared on the face of it to be a fairly innocuous degree of Irish self-government. But, as we will see, its implementation – and resistance to it – was the spark that set off armed revolution in Ireland.

The Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party was the institution that had made the issue of Irish autonomy its own. In 1912, it was still all but completely dominant in southern Irish political life and among Catholics in the north of Ireland also.

The IPP had a presence in every parish through its subsidiary organisation, the United Irish League. It held 70 Westminster seats out of 103 in Ireland and controlled virtually every corporation, town and county council of note outside Ulster. Its only serious nationalist electoral competitor was the All For Ireland League; a mostly Cork-based nationalist rival led by disaffected IPP members William O’Brien and Tim Healy, which in the election of 1910 took eight parliamentary seats.

The Party had also absorbed the Ancient Order of Hibernians around the turn of the century, a shadowy group that emerged out of Ulster secret societies in the late nineteenthcentury. Although disliked by the actual hierarchy of the Catholic Church (Cardinal Michael Logue of Armagh described them as ‘bullies’ and ‘a cruel tyranny’), the Hibernians had become a formidable Catholic-only nationalist fraternity and had also become, under the tutelage of Belfast MP Joe Devlin, the strong arm of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

It must have seemed, in 1912, as if the IPP would lead Ireland – gradually, legally – into Home Rule, and into what one of its leading thinkers, Tom Kettle, called ‘a union of equals’, but this would not happen. A decade of strife and revolution would sweep away the IPP, leaving barely a trace of its existence in much of Ireland.

Conventionally, the Party has been seen as simply unlucky; it was on the verge of triumph in 1912 before it was overtaken by a hurricane of events and buried by more radical rivals, who profited from a series of crises that began with the First World War.

Looked at a little more closely, though, the dominance of the Home Rulers in 1912 over Irish politics looks a little more tenuous. For one thing, the electorate in Ireland in the pre-First World War era was nearly three times smaller than after near-universal adult suffrage was granted in 1918. Furthermore, such was the dominance of the Party over Irish life in this era that many constituencies were not contested at all before 1918. The West Cavan constituency, for instance, where Sinn Féin scored a crucial by-election victory in 1917, had been represented at Westminster since 1904 by Vincent Kennedy of the IPP – who was returned, unopposed, in 1904, 1906 and 1910.40

The majority of the electorate that came to repudiate the Party in 1989, therefore, had never had a chance to vote for or against them before. If they were poor or women, it was because they did not have the franchise; if they lived in one of the many uncontested constituencies, it was because the Party’s internal selection had previously decided matters for them.

Secondly, the IPP’s nationalist credentials were becoming somewhat vulnerable by 1912. The Irish Party had been founded with a fair degree of influence from Fenians. Its founder, Isaac Butt, had campaigned for an amnesty for the insurgent prisoners of the abortive 1867 rebellion. The Party’s members annually commemorated, along with separatists, the anniversary of the execution of the ‘Manchester Martyrs’ – hanged in that same year. In the land agitation of the late nineteenth century, IPP MPs (including at one stage party leaders such as Parnell, and later John Redmond) had been imprisoned by the British authorities. In 1898 the Party had been to the forefront in organising centenary commemorations for the rebellion of 1798. During the Boer War (1899–1901), Irish nationalist MPs had often supported the Boers, or at least shown them sympathy. Some Irishmen in South Africa itself had even fought on their side against the British Empire.41

The Party’s base, therefore, still celebrated ‘fighting for Ireland’ and the idea that Irish nationalism was in a long struggle for ‘freedom’. But the Party itself had become almost part of the establishment of British-ruled Ireland.

True, its members were still not allowed to join the more exclusive clubs that so influenced the informal exercise of power, both in Dublin and in London, but the Party’s leadership was routinely consulted about the British Government’s choice of appointee for the post of Chief Secretary and Undersecretary for Ireland. Most of its MPs were from the elite of Catholic society, and by the 1910s had settled into British political life quite well, and viewed Home Rule, or autonomy within the United Kingdom and the Empire, as a sufficient measure of Irish independence.

Dramatic and violent events that exposed the contradictions between loyalties to the British political system and to Irish nationalist aspirations, such as the demands of total war and nationalist insurrection, would therefore expose also the contradictions within constitutional nationalism.

Thirdly, its long hegemony over much of Ireland had made the IPP somewhat arrogant, a little authoritarian and more than a little corrupt. In dealing with political rivals, the Party was not above using violence and chicanery. When in 1909 William O’Brien tried to launch his new party, the All For Ireland League, he was met with a considerable degree of violence from the strong arm of the IPP in the Ancient Order of Hibernians, whose members attacked rallies in County Cork and even fired revolver shots at a meeting trying to launch the new party in Mayo.42 In Dublin, where the challenge in municipal elections was from the radical nationalists of Sinn Féin and the socialists of various labour groupings, the IPP approach was less violent, but no more noble – using regulations to disqualify voters who might vote for their rivals.43

Nor was their exercise of power untainted. County Councils run by the Party were notorious for ‘jobbery’, nepotism and graft, while in some cases political power appeared simply a useful cloak for protecting economic interests. In Dublin, for instance, where overcrowding and shortage of decent housing for the poor had become critical issues by 1914, an inquiry into the collapse of two tenement buildings found that the Corporation, which had neglected to act on the issue, was dominated by slum landlords, most of whom were IPP members.44

In short, though the IPP appeared to be all-powerful in Irish politics in 1912, even had it not been for the eruption of war and rebellion, the expansion of the franchise would have left it vulnerable in the coming years to rivals who could portray it as corrupt, authoritarian and weak-willed with regard to Irish freedom.

Ripe for revolution?

In 1912, Ireland was neither entirely a colony – since it had its own elected representatives – nor entirely democratic, even by pre-First World War standards, since the real power lay with the London Government and with their appointees in Dublin. The large majority of Irish MPs (84 of 103 in 1910) were nationalists of one form or another, seeking self-government for Ireland.45 And Irish nationalism, even when expressed in constitutional terms, was not entirely loyal to the status quo. Irish nationalists and Catholics had been integrated to some degree into the British state, but this integration was still far from complete in 1912. This was the fundamental contradiction of British rule in Ireland by the early twentieth century and the one that left it vulnerable to revolt.