Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

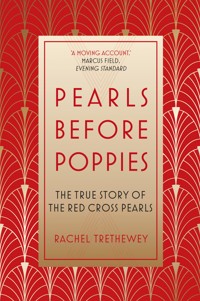

In February 1918, when the First World War was still being bitterly fought, prominent society member Lady Northcliffe conceived an idea to help raise funds for the British Red Cross. Using her husband's newspapers, The Times and the Daily Mail, she ran a campaign to collect enough pearls to create a necklace, intending to raffle the piece to raise money. The campaign captured the public's imagination. Over the next nine months nearly 4,000 pearls poured in from around the world. Pearls were donated in tribute to lost brothers, husbands and sons, and groups of women came together to contribute one pearl on behalf of their communities. Those donated ranged from priceless heirlooms –one had survived the sinking of the Titanic – to imperfect yet treasured trinkets. Working with Christie's and the International Fundraising Committee of the British Red Cross, author Rachel Trethewey expertly weaves the touching story of a generation of women who gave what they had to aid the war effort and commemorate their losses. In this new, updated edition, the last string of Red Cross pearls is revealed for the first time and the story behind their discovery told.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 527

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Mum,

for inspiring me.

First published 2018

This paperback edition first published 2019

The History Press

97 St Georges Place

Cheltenham, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Rachel Trethewey 2018, 2019

The right of Rachel Trethewey to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

ISBN 978 0 7509 8717 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Tears Transformed to Pearls

2 Famous Pearls

3 Pearls for Souls

4 Mother of Pearls

5 Patriotic Pearls

6 Pearls for Heroic Nurses

7 Pearls for Transformation

8 Pearls for Marriage

9 The Pearl Exhibition

10 The Pearl Poems

11 The Pearls in Parliament

12 The Kitchener Rubies

13 Pearl Mania

14 Pearls of Peace

15 The Pearl Necklace Auction

16 Pearl Rivals

Dramatis Personae

Postscript

Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Like the Red Cross Pearl Appeal itself, writing this book has only been possible thanks to the support of many people. When I first started my research, Jane High for the British Red Cross and Lynda McLeod at Christie’s welcomed me into their archives and were so generous with both their time and knowledge, their continuing interest in the project has been a great boost.

I am also particularly grateful to the many descendants of the women who gave pearls. Without access to their papers it would have been impossible to get a real insight into what motivated the donations. It was thanks to the Great War Exhibition at Port Eliot that I first had the idea for this book and when I told Lady St Germans my idea she was very supportive, providing me with colourful details about the family. Other relatives of Blanche and Mousie St Germans have also shared their memories with me; David Seyfried, Lord Herbert and Sir Michael and Lady Ferguson Davie sent me photographs and Blanche’s diary of her flying adventure, which showed just what a resilient woman she was.

The Wemyss/Elcho family tragedy lies at the heart of my story and so one of the most special times was visiting their timeless home, Stanway, in the Cotswolds. As I looked through the dusty files of letters and diaries in the muniment room, Mary Wemyss and Letty Elcho really came alive for me. Being shown around the house, sitting in Mary’s drawing room, looking at her photo albums and at the sketches of Letty and Ego Elcho by John Singer Sargent in one of the bedrooms made me even more aware of how the war destroyed their way of life. I cannot thank Lord Wemyss enough for his hospitality and for allowing me to use the family papers and pictures in my book. Mary Wemyss’ story is closely intertwined with her friend Ettie Desborough’s, and I would like to thank Viscount Gage and the British Library for allowing me to quote from her writing and photographs in her Pages from a Family Journal, which is a heart-rending memoir of a mother’s experience of the First World War. Similarly, I am grateful to the Trustees of the Bowood Collection for permitting me to use the papers of the 5th Marquess of Lansdowne and a photograph of him with his grandson, George Mercer Nairne, which so poignantly illustrate a father’s grief for his lost son. Bowood’s archivist Jo Johnston has been a sounding board for my ideas and has pointed me in the right direction for the material I needed.

Another highlight of my research was spending a stimulating afternoon with Philip Astor discussing his grandmother, Violet Astor. I am most grateful to him for allowing me to quote from the letters written to her about her remarriage and for the stunning photograph of her in her pearls which he sent to me. I would also like to thank Lady Emma Kitchener for a wonderful lunch and for showing me the photographs and belongings of her ancestor Lord Kitchener. Her enthusiasm for the human stories behind the great moments of history made her immediately understand what I was trying to do in my book. She provided me with just the information I wanted and, by telling me about her family’s love of animals, she helped me to crack the meaning of a donation which would otherwise have remained an enigma.

Noël, Countess of Rothes’ granddaughter, Angela Young, kindly provided me with information about her grandmother and the Leslie family. The Duchess of Westminster’s grandson, Dominic Filmer Sankey, was also very helpful, telling me about the complex dynamics of the Grosvenor family after his grandparents’ divorce. I was given an insight into life in the wards at the Duchess of Westminster’s Hospital through reading Nurse Martha Frost’s scrapbook and I am grateful to her nephew, Ian Broad, who has agreed to me quoting from it.

With the Duke of Rutland’s permission, Peter Foden, the archivist at Belvoir Castle, gave up his time to try to find out the history of the pearls which the Duchess of Rutland gave to the Red Cross appeal. Lord Rowallan and his aunt, Fiona Patterson, also tried to discover what had happened to the pearl necklace bought by their family at the Red Cross Auction. Emma Clarke at Mikimoto, London, provided me with additional information on Kokichi Mikimoto and the history of cultured pearls. Otley Museum and Archive Trust’s Margaret Hornby sent me Legacies of War: Untold Otley Stories and Barbara Winfield looked into Ada Bey’s role in Otley during the First World War.

I am also indebted to the many archives and museums which have granted me permission to quote from letters and reproduce illustrations in their collections:

The Canadian War Museum, for the letters of Katherine MacDonald, her family and friends, the photographs associated with her and the painting of No. 3 Canadian Stationary Hospital at Doullens by Gerald Moira; the Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies for the Desborough Papers; the Somerset Archives and Local Studies Service (South West Heritage Trust) for the de Vesci Papers; the Devon Archive and Local Studies Service for information on the Kekewich family; the Imperial War Museum for a letter from Lord Kitchener’s sister and one from his cousin written in 1916 – we have been unable to find the current copyright holders of these letters but every reasonable effort has been made to seek permission. Thank you to the British Red Cross Society for the letters between Sir Robert Hudson and Lord Northcliffe, which are held at the British Library, and the Grafton Galleries Red Cross Pearl Exhibition poster which is held at the Imperial War Museum; the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, for Arthur Percival Marsh’s letter about the Duchess of Westminster’s Hospital; the Parliamentary Archive for letters to Andrew Bonar Law, David Lloyd George and Hansard. My thanks also to Her Majesty the Queen and the Royal Collection Trust for their photographs of Princess Victoria wearing pearls, and Queen Mary and Queen Alexandra’s visit to the Pearl Exhibition at the Grafton Galleries; the Lafayette Negative Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum for photographs of Lady Northcliffe and the Duchess of Westminster; the National Portrait Gallery for a portrait of Blanche St Germans.

The Mary Evans Picture Library kindly supplied photographs of many of the people written about in the book, and Christie’s Archive provided two cartoons, one entitled ‘For the Wounded’ and the other by Max Beerbohm of the Red Cross auctions. The British Library supplied a photograph of the Countess of Cromer which appeared on the cover of The Queen newspaper.

As well as manuscript sources, I am also grateful to have been allowed to quote from printed sources. My thanks go to Rosalind Asquith and Tom Atkins at Random House for the use of Cynthia Asquith’s books, her writing evocatively captured the experience of her society. To Sophie Scard of United Agents who, on behalf of Jane Ridley, agreed that I could quote from Jane Ridley and Clayre Percy’s book, The Letters of Arthur Balfour and Lady Elcho 1885–1917. My understanding of what it was like to live through the war has also been enhanced by reading many contemporary newspapers. The accessibility of online sources including The Times, the Daily Mail and The Spectator archives, the Illustrated First World War and the British Newspaper Archives made my task much faster and easier.

I would also particularly like to thank the people who shared my belief that this was a story worth telling. My agent, Heather Holden-Brown at hhb agency, has been immensely supportive from when I first came to her with the embryonic idea. Her assistant, Jack Munnelly, has also been a great help. My publisher at The History Press, Sophie Bradshaw, has had the same vision for the book as I have and this has made it an exciting project to work on together. I would also like to thank Lucy Keating at the British Red Cross, whose enthusiasm for the idea in the initial stages was energising.

Finally, I want to thank my friends and family who have patiently put up with my obsession with the Red Cross Pearls for several years. Christopher Wilson, Andrew Wilson, Marcus Field, Kay Dunbar and Stephen Bristow have helped me with their experience of the literary world. My husband, John Kiddey, joined me on my research trips, photographed countless letters and discussed what we found – he has been the perfect person to share those experiences with. My son, Christopher, helped me with technical challenges or any computer related problems, while my sister, Rebecca Trethewey, was a great proofreader. My last thanks, which should really come first, go to my mother, Bridget Day, who inspired me in so many ways to write this book.

INTRODUCTION

I have always been a pearl lover. For me, their natural lustre is more alluring than the glitter of diamonds. Worn next to the skin every day, not just for special occasions, they are the most intimate of jewels. My grandmother told me that pearls reflect the health of the woman who wears them and that, when my great-grandmother was dying of cancer, all her pearls turned black. It was just one of the stories she shared with me when, as a child, I spent many spellbound hours sitting on her bed looking through her jewellery box with her. For me, a string of pearls has always represented the links between one generation of women and another, as mother to daughter, grandmother to granddaughter, they pass on stories of family celebrations, happiness and sorrow, love and loss. When my grandmother died, she left me her two-strand pearl necklace with a sapphire and diamond clasp. It is my most precious piece of jewellery and I wore it on my wedding day as a tangible connection between my old and new life.

I am still attracted by the subtle seductiveness of pearls, so when I went to Port Eliot Festival in the summer of 2014 it was not the eclectic mix of bands, books and bohemians that stuck in my memory but a story about those jewels. As I went around the exhibition about the effects of the First World War on the St Germans family and the tenants on the Port Eliot Estate, one line on the large storyboards particularly fascinated me: In 1918, Emily, Countess of St Germans gave a pearl, which had belonged to the Empress Josephine, to the Red Cross Pearl Necklace Appeal. Intrigued, I wanted to know more.

Emily had a special reason for donating one of her most precious jewels to the British Red Cross. At the beginning of the war, her son John Cornwallis Eliot, 6th Earl of St Germans, known as ‘Mousie’, became a captain in the Scots Greys. Tall, athletic and handsome, he was ‘an amateur comedian of no mean ability’, who often entertained his friends. After fighting in the Battle of the Somme and at Ypres, he was awarded the Military Cross in recognition of several acts of gallantry. He was severely wounded and sent home. Fortunately, unlike so many of his comrades, he survived. When the countess gave her pearl, she was giving thanks for her son’s survival while also remembering the loss of so many other men from the estate who had died in the war. In March 1918, as she sent her gift, Emily had another cause to celebrate. ‘Mousie’ had got engaged to Blanche ‘Linnie’ Somerset, daughter of the Duke of Beaufort. With their wedding planned for June, Lady St Germans could at last look forward to the future with hope.

Discovering Emily’s story made me want to find out which other women gave pearls to the Red Cross and what were the stories behind their gifts? As celebrations of the centenary of the Great War reached a crescendo with the Poppy Appeal at the Tower of London, I thought more about the pearls. I discovered that before the sea of poppies there was an ocean of pearls. I also found out that using these jewels to commemorate the sacrifice made in the First World War pre-dated selling artificial poppies as a symbol of remembrance for charity. A French woman, Anna Guerin, originally had the idea, which was then adopted by the British Legion, who held their first poppy appeal in 1921.1

The Red Cross Pearl Appeal had been launched three years earlier, in 1918, to raise funds for the wounded while paying tribute to the brave servicemen who had fought for king and country. Each pearl represented a life. No jewel could have been more appropriate. For thousands of years pearls had been symbolically linked to mourning. In Greek and Roman mythology it was believed that pearls were formed from teardrops of the gods falling into oysters. The link between these miracles of nature and grief was expressed by Shakespeare in Richard III, ‘The liquid drops of tears that you have shed, Shall come again, transform’d to orient pearl’.2 However, although associated with loss, pearls also represent hope and resurrection. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, which dates back to 2100 BC, pearls were described as ‘a flower of immortality’. In the Bible, they symbolise purity and perfection and are associated with Christ, the Virgin Mary and the Kingdom of Heaven. In Matthew 13, Jesus compared the Kingdom of Heaven to a ‘pearl of great price’.3 Pearls also feature in the description of the new Jerusalem in Revelations, ‘The twelve gates were pearls, each gate was made from a single pearl.’4

Like the 2014 Poppy Appeal, the 1918 pearl necklace collection developed a momentum all its own. At first, the Red Cross had wanted to gather enough pearls to make one necklace, but the appeal captured the public imagination and jewels poured in from around the world until there were nearly 4,000, enough to make forty-one necklaces.

This book interweaves the story of the Pearl Necklace Campaign with the personal stories behind individual pearls. Like the pearls that make up a string, each story is complete in itself but when joined together with the other wartime experiences it creates a wider picture. Through the pearls we gain an insight into a world that was changing forever. The pre-war certainties of the pleasure-seeking Edwardian era were shattered by the Great War. Heroic young men, who saw themselves as riding into battle like medieval knights in a Christian Crusade, lost their lives in the industrial-scale carnage of modern warfare. Although this book describes their valour, rather than being about the battlefields of the Great War it is primarily about the home front. It does not aim to provide a social history of all sections of society, since only women from the higher strata of society could afford to give pearls. However, bereavement was a great leveller, and the grief experienced by a mother, wife or lover cut through class barriers.

The pearls were a uniquely feminine way of paying tribute to the fallen. Some mothers who donated had lost two or even three sons in the war. Many of the young widows who gave were left with small children who would never remember their fathers. Their grief was often overwhelming, but so was their courage in facing bereavement. Instead of surrendering, they showed an indomitable spirit worthy of their men and carried on. The pearls provided an evocative outlet for their grief. Amidst the horror and devastation of war, these very personal gems represented more than just jewels; their beauty was a reminder of gentler pre-war days and they showed that civilisation would not be destroyed by the barbarism of the Great War. Using them to raise funds for the Red Cross emphasised that humanitarian values would not be beaten.

In this book there are many tragic stories, but there are also tales of joy, new love and transformed lives. For centuries, pearls have been associated with female empowerment, both Cleopatra and Elizabeth I used pearls to symbolise their power and status. The Red Cross Pearls also reflect dauntless female strength of character and they remind us of what women can achieve when faced with the most extreme circumstances. The Countess of Rothes rowed a lifeboat to safety from the Titanic and went on to donate one of the pearls she was wearing on that fateful night to the appeal. The selfless sacrifice of the young Canadian nurse Katherine MacDonald, who lost her life while caring for the wounded, was also commemorated by a pearl.

Although the Red Cross Pearls have been largely forgotten by history, in 1918 they were the talk of society. They were discussed over candlelit dinners in country houses, in the senior common rooms of universities and in newspaper newsrooms. By the summer, their fate was even debated in Parliament. What began as a collection among an interconnected elite spread across the country, and eventually the world, to touch the hearts of women from many different backgrounds. Pearls poured in from Egypt, South America and Singapore. They were given in memory of soldiers and nurses, not only from Britain but from Canada, New Zealand and Australia. In the final necklaces each pearl became anonymous, a gem from the queen could be next to a jewel from a poor widow, but each one was of equal sentimental value.

Although the Pearl Appeal was predominantly a tribute from women, it was supported by powerful men. Tracing the history of the pearls takes us behind the public façade of some of the most influential men in the war to reveal their human side. It shows the newspaper proprietor Lord Northcliffe mourning for his nephews, the politician Lord Lansdowne grief-stricken about the loss of his favourite son, and the icon of the army, Lord Kitchener, devastated by the death of his protégé Julian Grenfell. Examining this intimate history gives an additional dimension to understanding their attitudes to the war.

The full story of the Red Cross Pearls has never been told before. Using research from the Red Cross and Christie’s archives, and the extensive contemporary coverage of the Pearl Appeal in The Times, the Daily Mail, The Sketch, the Illustrated London News, The Queen and provincial newspapers, this book pieces together its inspiring story. Drawing on diaries, journals and letters of the people who gave pearls, it explores the emotions and experiences that motivated so many women to donate.

Through these contemporary records, we are able to enter the mindset of some of the women going through this tragedy. We get an insight into the complex emotions of Letty Elcho and Violet Astor, the young widows who had lost their soulmates, and Mary Wemyss and Ettie Desborough, the mothers who had to come to terms with the deaths of two of their sons. Reading how they reacted is often a heart-breaking experience and, for our generation, with its different attitudes to duty, faith and patriotism, it is sometimes hard to understand. It shows that their individual responses were as unique as each pearl and even women who were the closest friends reacted in very different ways. Whether it was the Duchess of Rutland doing everything in her power to prevent her son going to war or Ettie Desborough glorifying the sacrifice of her sons, what becomes clear is that they did what they needed to survive. Before judging them, we should consider what we would do if we were faced with a similar situation.

Remembering the sacrifices made by the women who donated pearls is deeply moving. The Red Cross Pearls are a tribute to them as much as to their men. Ultimately, their generosity reflected their faith in a selfless love which could transcend tragedy. As The Times wrote:

And so one is brought back in the end to look with reverence, upon the heart of this gift of pearls […] It is the memories and the tears of mothers, wives and lovers. Of these thousands of pearls not one is merely a pearl. It is a proud memory of one who proudly died for freedom; it is a tear shed in secret over an irreparable loss; a shining tribute to a man or to a band of men […] who gave their all to win all for those whom they loved.5

ONE

TEARS TRANSFORMED TO PEARLS

Last night – we went off to bed about 11.30 and no one spoke of sitting up to see the New Year in and poor 1917 slunk away in silence, shame and sorrow. I kept the window open and I heard bells ringing in my ears and fell sadly asleep, feeling too dull and apathetic to cry.1

These were the despondent words written by Mary, Countess of Wemyss in her red leather diary on New Year’s Day, 1918. She was not alone in her depression – after three and a half long years of fighting, Britain was war-weary. Mary, and thousands of women like her, had waved off their loved ones to fight for king and country, to see many of them never return, slaughtered in the fields of Flanders, on the cliffs of Gallipoli or in the deserts of the Middle East. One loss followed another so relentlessly that families were left dazed. So many tears had been shed that the bereaved were almost beyond crying.

As well as the emotional exhaustion, there were practical problems that added to the demoralising atmosphere in Britain. With shortages of supplies, exacerbated by the heavy demands over Christmas when large numbers of soldiers had come home on leave, food became a national obsession.2 The winter of 1917–18 was the winter of the queue; at first this affected the working class most, but soon middle-class women who could no longer get servants joined them. In freezing weather, sometimes standing in inches of thick snow, they spent hours in the long lines that snaked outside the shops where small amounts of tea, sugar, margarine or meat were still available.3 In many parts of the country there was no butter or margarine to be had; butchers had to close for several days a week because they had no meat, while fish and chip shops shut because they had run out of fat.4 Concerned by the appearance of food queues, from January 1918 the government issued ration cards and began to build up a system of regional and local food distribution centres.5 With no end to the war in sight, morale was at such low ebb that the army feared people at home would fail them by losing heart to see the war through to victory.6

In the first months of 1918 Britain’s prospects of winning the war had never looked bleaker. Once Russia withdrew from the war, following the Bolshevik Revolution, the Germans were able to concentrate their best troops on the Western Front. The British forces were in a poor state to fight back because, after the casualties of the previous year, their army was dangerously under strength. The master of German strategy, General Erich Ludendorff, knew that he had a brief window of opportunity during which his enemies were weak; his aim was to defeat Britain and France quickly before the Americans arrived in large numbers to support the Allies.7 For civilians there was no escape from thinking about the war. The Germans’ intensive night-bombing of London and the south-east added a new dimension of terror at home. For many women, it was only the desire to find some meaning in their losses that made them continue to stand firm.8

Nearly every family had been touched by bereavement; if they had not suffered it personally they had friends who had lost a loved one. It was clear that a deep well of grief existed, which needed to be expressed. In an age of stoicism there was no room for hysteria, instead the women of the country needed a dignified way to remember their loss with pride. These patriotic and practical women wanted to help the soldiers who were still fighting. Hospitals at home and abroad needed staff and equipment to give the wounded the best chance of survival, while those who had been maimed in the conflict deserved the highest quality of care once they returned home.

The British Red Cross was at the heart of providing this vital support. Following the outbreak of the war, the Red Cross had formed the Joint War Committee with the Order of St John of Jerusalem. The two organisations worked together and pooled their fundraising activities and resources for the duration of the war.9 However, by 1918 they needed £3 million a year – or £10,000 a day – to keep going.10 Women across the country had already given so much to the cause; they had run flag days, held bazaars, put on concerts and donated whatever they could afford. Yet their generosity was not exhausted and, when provided with an innovative idea that recognised the extent of their sacrifice, they were ready to give again.

It was at this critical moment that Mary (known as Molly) Northcliffe, wife of the press baron Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, stepped in with the perfect plan to reinvigorate the women of Britain and the Empire. She would ask them to give a pearl from their precious necklaces to make a new string of pearls, which would be sold in aid of the British Red Cross. Each jewel would represent a life changed forever by the war. The appeal was very much a reflection of Molly Northcliffe, and without her inspirational leadership it would not have become such a resounding success.

By 1918, Lady Northcliffe was at the peak of her powers. In her late forties and recently made Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire for her charitable work during the war, on 9 January 1918 a full-page photograph of her graced The Sketch. Looking like the modern incarnation of Britannia, her steady gaze engaged readers. Fashionably dressed in a toque and velvet opera coat, with her hands placed on her hips opening her coat to reveal a cascade of pearls, she exuded confidence. Looking poised and uncompromising, she embodied all the women who had found a new sense of purpose through their war work. Recognising their role, in the summer of 1917 the government had introduced this new order of chivalry. The Order of the British Empire (OBE) was used to honour civilians for their contribution to the war. It was soon known as ‘Democracy’s Own Order’, reflecting just how much women had done for their country, it was the first order of chivalry to admit them on equal terms with men.11

However, although the majority of new OBEs had shown real commitment to the war effort or bravery – for instance, saving the lives of fellow workers in munitions factory fires – the new honour soon gained a bad reputation. The public impression was that it was a tawdry bauble awarded to society hostesses, time-servers and war profiteers for trivial acts. It became known as the ‘Order of the Bad Egg’, ‘Other Buggers’ Efforts’ or the ‘Order of Bloody Everybody’.12 Reflecting this critical perception, in a column in Tatler, ‘Eve’ commented on the unprecedented number of women honoured in the recent list. Expressing ambivalence to the new awards, in her usual tongue-in-cheek tone, ‘Eve’ explained that ‘our grandmothers’ would have fainted with surprise to see as many women as men in the honours list, particularly as the majority of them were ‘honoured’ for doing jobs which were once seen as exclusively masculine. The columnist joked that if there were more lists like this ‘the chief distinction, if not honour, will be not to have letters after your name’. She added, ‘I’ve already heard of one Wicked Woman who appends DNWW to her well-known name – which, being interpreted, means Done No War Work.’13

Lady Northcliffe was too self-assured to be put down by such mocking comments. The Sketch picture of her shows a woman ready to launch the most ambitious charitable campaign of her career. Molly had the experience, connections and imagination to make the appeal take off. After founding a newspaper empire which, from 1908, included the establishment’s ‘Thunderer’, The Times, as well as the Daily Mail, her husband, Lord Northcliffe, was one of the richest and most influential men in British life. At the beginning of the war Northcliffe controlled four out of every ten morning newspapers.14 Politicians feared and courted him, knowing that his newspapers could help to make or break governments.

Molly had been a true partner in her husband’s meteoric rise. In the Pearl Appeal, as in their life together, she drew on her husband’s considerable resources while distancing herself from his sometimes socially embarrassing vendettas. In her Red Cross campaign, Molly used the skills she had honed while advancing her husband’s career.

When they married in 1888, Alfred and Molly had little money but endless dreams set out in the groom’s ‘Schemo Magnifico’, a brown paper folder containing his ideas for building a newspaper empire. With no inherited money to rely on, as he was the son of an impoverished barrister while she was the daughter of a West Indies sugar importer, the young couple were determined to make their own fortune. On their wedding day, Alfred borrowed the money from a friend to pay for the engagement ring and appeared at the church with a ‘dummy’ copy of his planned penny weekly, Answers to Correspondents, sticking out of his jacket pocket. His domineering mother predicted that the couple would have many children and no money – she could not have been more wrong.

Later, Lord Northcliffe attributed much of his success to his wife’s sure judgement and quick brain. She knew what made a story that would appeal to women, and she used this knowledge first in her husband’s newspapers and then in the pearl campaign. In the first years of their marriage, she worked side by side with Alfred in the little front room of their terraced house in Pandora Road, West Hampstead, writing articles and collecting interesting material from American newspapers for Answers to Correspondents. Across the floor were strewn newspaper clippings, papers, scissors and paste, while proofs were draped over the armchairs. Both husband and wife looked back on this time as a period of great happiness, as they were working together with a common purpose.

Molly’s influence was important again when Alfred founded the Daily Mail in 1896. Wanting to attract women readers whose interests had previously been largely ignored by the press, he made it the first newspaper with a dedicated women’s page, known as the ‘Women’s Realm’. Molly gave him hints about the type of stories which would interest women readers. No doubt thinking of his socially aspirational wife, when giving advice to his young colleague, Tom Clarke, Alfred explained that women readers were most interested in other people, their failures and successes, their joys and sorrows and their peccadilloes. He told him that the more aristocratic names he got in the paper the better, because the public was ‘more interested in duchesses than servant girls […]. Everyone likes reading about people in better circumstances than his or her own.’15 Two decades later, Lady Northcliffe applied the same principles to reach the same female audience with the Pearl Appeal; it combined the glamour of the aristocracy humanised by the pathos of the war.

Unlike many of the women who were to donate pearls, Molly had not lost a son in the war. Instead, the great sadness in her life was to be childless. Both husband and wife had longed for children, and when Molly did not conceive naturally, the most skilled doctors in England and on the Continent were consulted, but none could find a medical explanation. In April 1893 Molly underwent surgery but it was unsuccessful. Their childlessness remained a permanent disappointment to them both.

Alfred did have illegitimate children, but he never had the heir he could publicly acknowledge to the world. When sympathy was offered, Alfred would brush it aside, simply saying that in every life ‘there is always a crumpled rose leaf’.16 Described as boyish, he had a natural affinity with children and built a strong relationship with his many nieces, nephews and godchildren. He kept a cupboard of toys in his newspaper office and would sit on the floor playing with his young guests on their regular visits. He also gave generous gifts to employees for their children.

Molly’s unhappiness was reflected in her poor health. In the early years of their marriage she suffered from double pneumonia which affected her heart. The psychological effect of infertility on her mood is plain to see in a photograph taken at this time. While Alfred dominates the photo, staring into the distance with one foot resting on a stone mounting block, one hand on his hip, the other proprietorially placed on Molly’s shoulder, she looks desperate. Her eyes are downcast, her shoulders hunched, her whole demeanour is as fragile as the delicate lace on her cream blouse.

However, being fundamentally feisty, Molly did not sit back and wallow in self-pity for long; instead, she carved a new and independent life for herself. Called by her husband ‘my little lion-heart’, she was known for her fearlessness. She would ride the most spirited horses, drive as fast as possible in early motorcars and was one of the first women to go up in an aeroplane.17 When her husband started having affairs, she also took lovers, including one of Alfred’s most trusted colleagues, Reggie Nicholson.

Educated at Charterhouse, Reggie first helped to run the Northcliffes’ household finances, but later held important newspaper posts. He often travelled abroad with the couple; his easy charm and tact made him invaluable to them both. It seems that Lord Northcliffe knew of the affair and accepted it because he valued and respected his wife too much to divorce her. Although he became increasingly irritable and volatile in private, he remained courtly in his outward devotion to her. Resting on an easel in his office at Carmelite House was a regal portrait of Molly surrounded by flowers. In his diaries, he called her ‘the little wife’, ‘wifie’ and ‘wifelet’, but while the diminutives suited her ‘dainty’ physique, he knew that she was no little woman, instead she was his equal.18

Importantly for Molly, Alfred gave her a generous allowance to fund her opulent lifestyle. In return, she tolerated his infidelities and publicly played the role of a loyal wife to perfection. While he spent time with his mistress Kathleen Wrohan and their three illegitimate children at Elmwood, his country house at Broadstairs in Kent, Molly stayed for extended periods in their London town house or at Sutton Place, a Tudor mansion near Guildford. Sutton Place became the ideal show home for Molly to demonstrate her impeccable taste and skill as a society hostess. Lavishly spending her husband’s growing fortune, she made sure that every aspect of the house was finished to her exacting standards. Sutton Place was described rhapsodically in The Sketch as a place where guests could wander in the famous rose gardens cultivated by Lady Northcliffe, or walk by the stream where ‘yellow and blue lilies gaze at themselves’ and which was ‘so full of charm and serenity that Ophelia would have changed her resolve when nearing it’.19 For the more energetic there were tennis courts and the first private golf course in England to enjoy. The less sporty could relax in the many nooks of the historic house or view relics of Lord Northcliffe’s hero, Napoleon, in the panelled gallery.

The contacts Molly made helped to make the Pearl Appeal one of the most fashionable fundraising campaigns of the war. At their house parties, the Northcliffes entertained an eclectic mix of politicians, journalists, society figures, actors and actresses from Britain and abroad. While Molly was known for her fascination with the aristocracy, Alfred was not motivated by snobbery so much as the desire to make contact with other people of exceptional achievement. As a newspaper tycoon, he wanted to know exactly what was going on in the world. During dinners he would listen attentively to what was said but often retired early to bed, leaving his wife to entertain their guests. While Alfred was never totally at ease in social settings, Molly moved with grace to the heart of pre-war society. She was able to charm not only her husband’s friends but also his enemies.

Although Northcliffe always remained an outsider, never quite accepted by the landed aristocracy, he could not be ignored by the ruling elite. His mass-market newspapers reflected the growth of democracy. In exchange for his services to the Conservative Party, Alfred was made a baronet in 1904, and a year later he became the youngest peer ever created. The culmination of his career came just months before the launch of the Pearl Appeal in November 1917 when David Lloyd George made him a viscount. A social mountaineer, Molly relished each elevation and saw it as her triumph as much as his. When Alfred became a baronet, she congratulated him, adding that her happiest thought was that they began life together and she had been with him through all the years of hard work that had earned him his distinction and fortune so young.

Without children to distract her, Molly threw her considerable energy into philanthropy. During the war she became a doyenne of charity fundraising. She served on countless committees, ran her own private hospital and took a prominent part in the control of Red Cross finances and operations. Lord Northcliffe also worked hard for the charity, collaborating closely with Sir Robert Hudson, the chairman of the Red Cross and St John’s Ambulance Joint Finance Committee. Northcliffe used his newspapers to promote the work of the Red Cross through The Times Fund. Since the war began, The Times had donated significant advertising space to the organisation almost daily and free of charge. It was a generous gesture at a time when newspapers had been forced to reduce the number of pages they produced due to a drop in advertising revenue and paper shortages. By 1918, the situation became even worse when paper rationing was introduced and the allocations to newspapers were reduced by 50 per cent.20

Throughout the war years, the paper informed its readership about what the Red Cross was doing. In November 1915, The Times produced free with every copy a Red Cross supplement of thirty-two pages containing full descriptions of the charity’s work with illustrations and maps. Determined to use his journalistic skills for the war effort, Alfred went to France to see for himself how the war was being conducted. In 1916, he published his At the War book about the work of the Red Cross and life at the Front. All royalties from the sales were donated to the charity. Fifty-six thousand copies of the book were sold in the English edition alone and the Red Cross received over £5,000 in the first six months of sales.21

During the war, Northcliffe was one of the most powerful propagandists in Britain. In 1918 Lloyd George made him Director of Propaganda in Enemy Countries, but he had been using his newspapers to undermine enemy morale throughout the war. He was one of the Germans’ greatest hate figures. In 1914, a medal was struck in Germany showing Northcliffe on one side, sharpening a quill pen, and on the other a devil stoking flames, with the caption, ‘The architect of the English people’s soul’. Similarly, a 1918 German cartoon showed the devil in an inquisitor’s robe with one arm around a rotund Lord Northcliffe, who was dressed in a vulgar checked suit and had a threatening look on his face, holding a copy of The Times in one hand and the Daily Mail in the other. In the caption, Satan said to Lord Northcliffe, ‘Welcome, Great Master! From you we shall at last learn the science of lying.’22

Northcliffe was perceived as such a threat by the Germans that they launched a direct attack on his country home, Elmwood, which was on the Kent coast. On a cold night in February 1917 the house came under a barrage of shells from a German destroyer. Shrapnel burst around the house, with some hitting the library. Alfred survived unharmed but his gardener’s wife, who was with her baby 50 yards from the house, was killed and two others were badly wounded.

Like so many families in Britain the Northcliffes lost loved ones in the war. Four Harmsworth nephews, who had been like sons to the couple, were killed in action. Vere Harmsworth, the son of Alfred’s brother, Harold, wrote home in October 1916 warning that he might be killed. Aged just 21, he explained that he could not imagine himself growing old. If he fell, he asked his family not to mourn but to be glad and proud. He believed that his death was the price that had to be paid for the freedom of the world and that they should see his life as not wasted but gloriously fulfilled.23 Vere was killed shortly after writing this letter. His self-sacrificing sentiments reflected the attitude of so many young men who were to be immortalised through the Pearl Appeal.

Another nephew, and son of Harold Vyvyan Harmsworth, who had joined the Irish Guards a few days after the outbreak of war, was wounded for the third time and died on 12 February 1918. When the news was broken to him at his desk, Lord Northcliffe cried out, ‘They are murdering my nephews!’24 Yet another family death just as the Red Cross appeal was launched gave a very personal impetus to Molly’s crusade. The determined society hostess called on all her contacts and ran the Pearl Appeal like a military campaign.

On 27 February it was announced that a committee had been formed with Lady Northcliffe as its chairman. Giving the royal seal of approval, Princess Victoria, the spinster sister of King George V, agreed to be president of the appeal. Tall and elegant with large expressive eyes, the princess was the right person to encourage other royalty to donate. Although she could sometimes be sharp-tongued, she was seen as ‘the good angel’ of the family, the unmarried daughter, sister and aunt, who sacrificed her own needs for others. After her father, Edward VII’s death she lived with her elderly, stone deaf mother, Queen Alexandra. Although she had little in common with her sister-in-law, Queen Mary, who she described as ‘deadly dull’, she was particularly close to her brother, the king. Sharing a sense of humour and a similar outlook, they spoke daily on the telephone.25 As president of the Pearl Appeal she took her role seriously and was to be an active member of the committee, not just a figurehead.

Reflecting the interconnections and intricate morality of the Edwardian era, also on the steering committee was Alice Keppel, the mistress of Princess Victoria’s father, Edward VII. Evidently Lady Northcliffe had no qualms about drawing on both women’s talents. As a woman of the world herself, Molly understood the subtle rules of the game; affairs were acceptable providing appearances were kept up and everyone behaved with tact. Sitting around a committee table with her father’s ‘La Favorita’ was much less highly charged for Princess Victoria than an earlier occasion where both women were thrown together. When Edward VII was dying, Mrs Keppel sent the queen a letter the king had written to her in 1901 when he had appendicitis. In it he explained that if he were to die he wanted to say goodbye to her. Queen Alexandra agreed to her husband’s wish and both wife and mistress met by the deathbed. According to Mrs Keppel, the queen shook hands with her and said she was sure that she had always been a good influence on her husband. Alexandra then turned away and walked to the window. The king had a series of heart attacks and kept falling forward in his chair, by this time he was so ill that he did not recognise his mistress. When the usually poised Mrs Keppel became distraught, it was Princess Victoria who gently escorted her father’s great love from the room and tried to calm her.26

Kind and generous, Alice Keppel was a popular member of society. She was ready to use her charm to encourage her friends to give pearls. She was also an expert on jewellery, having received a priceless collection of love tokens from the king. One of the couple’s favourite jewellers was Fabergé. At Christmas 1900, she had a gold cigarette case designed for her lover by the jeweller, enamelled in royal blue with a coiled serpent studded in diamonds. Showing the magnanimity expected of her, another year she advised the king on a gift for his wife. Queen Alexandra also collected works by Fabergé and, thanks to Mrs Keppel, the king commissioned gold models of all their Sandringham animals for her. Habitually dressed in gowns by Worth and diamond and pearl chokers, Alice was renowned for her jewellery. Her daughter Violet wrote that she always imagined her wearing a tiara. She added that her mother had a goddess-like quality, but any pedestal she was placed on would have to be made by Fabergé.27

Also in the inner circle on the executive committee was Lady Sarah Wilson, the sister of the Duke of Marlborough and aunt of Winston Churchill. She was a close friend of Mrs Keppel, and as they were so often at the same house parties Lady Sarah became known as her ‘lady-in-waiting’. Both women had sat together at Edward VII’s coronation at Westminster Abbey in a special pew reserved for the king’s girlfriends, past and present, humorously referred to as ‘the king’s loose box’.

Lady Sarah had also known the Northcliffes for many years. During the Boer War, Alfred had made her the Daily Mail’s first female war correspondent, sending back stories which were aimed at women readers. During the winter of 1899, trapped in the besieged garrison of Mafeking with her husband Lieutenant Colonel Gordon Chesney Wilson, she kept a diary for the Daily Mail. She gained a huge following of readers, who liked her down-to-earth writing style and optimistic attitude. Although the situation at times seemed desperate, she did not dwell on the horror. Despite food shortages meaning they had to eat horse sausages, minced mule and curried locusts, she also described the more positive side, including cycling events and the celebrations for Baden-Powell’s birthday. When the siege finally ended after 217 days in May 1900, there were widespread celebrations back in Britain. Spirited Lady Sarah was treated as a heroine. The Daily Mail published a picture of their ‘lady correspondent’ wearing a large black hat topped with plumes and bows and her bravery was lauded as a symbol of the British ‘bulldog spirit’.

During the First World War she called on that spirit once again. Within days of the war being declared she posed for a photograph with a bulldog and a resolute expression on her face, appealing for funds for a hospital. After her husband was killed in action in November 1914, she dedicated all her energy to the war effort. With her sister-in-law, Lady Randolph Churchill, she raised money for free buffets for soldiers and sailors at railway stations. Rather daringly she also sold lingerie in a shop in Piccadilly to raise funds for the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. She was a useful member of the Pearl Committee because of her journalistic ability and her experience in asking her friends to donate heirlooms. Earlier in the war she had appealed for art and furniture to sell to raise money for the hospital she was setting up for the Belgian Army.28

Soon, nearly every society woman in London wanted to be involved in the pearl gathering. Lending their names to the cause were nine duchesses, twenty-seven countesses and dozens of viscountesses. The wife of the American ambassador, Mrs Page, and even the glamorous Princess of Monaco appeared on the list of patrons. Demonstrating her ability to distance herself from her husband when necessary and run the appeal as a formidable woman in her own right, Molly pulled off the considerable coup of persuading both the present and previous prime ministers’ wives, Margaret Lloyd George and Margot Asquith, to serve on the appeal’s general committee.

Margot Asquith loathed Lord Northcliffe with a passion, believing he represented a force of evil in public life because he very publicly criticised her husband’s running of the war. Using the full force of his newspapers, Northcliffe had attacked Asquith’s government for the high-explosive shell shortage, which he blamed for the death of many British soldiers. Under increasing pressure, Asquith’s Liberal government fell in May 1915 and was replaced with a coalition government with Asquith still as prime minister but David Lloyd George as the Minister of Munitions. At this time, Northcliffe admired Lloyd George, seeing him as another self-made man of outstanding ability, he called him ‘the little wizard from Wales’.29

In the following months, Northcliffe’s unrelenting attacks on Asquith continued. By this point Margot Asquith became increasingly hysterical, writing in her diary that she would like to see the press baron arrested and claiming that because he encouraged the generals and politicians to quarrel, Germany had no better friend than him.30 In the political crisis of December 1916, which brought the Asquith government down, Alfred gave his support to Lloyd George becoming the new prime minister. Historians debate the extent of Northcliffe’s role in events; most agree that he helped to create a hostile atmosphere for the government, but his direct involvement in the final manoeuvring was limited. However, Northcliffe liked to see himself as a powerbroker. When the government collapsed, he phoned his brother Cecil and asked, ‘Who killed cock robin?’ Cecil replied with the answer he wanted, ‘You did.’31

The fact that the wives of the men at the centre of these bitter political struggles could put aside their differences for the sake of the cause illustrates the strength of the Red Cross appeal and how it was fast becoming the most fashionable charity fundraiser of the era. At a meeting to launch the campaign at the Automobile Club, Lady Northcliffe rallied her troops. Emphasising that this was women’s special tribute to the men who fought, while joking about the new right of some women aged over 30 to vote (which became law on 6 February 1918), she began:

Your Royal Highness, ladies and gentlemen – You observe that I have put man in what is now regarded as his proper place. We are not concerned, however, to-day with women’s rights, it is women’s duty which brings us here. Our plan is to collect from willing givers pearls which shall make an historic necklace to be sold eventually for the benefit of the sick and wounded.32

She called on the owners of beautiful pearls to give from their strings and to persuade others to donate. A little laugh went around the crowded room when she remarked that no one would miss one pearl from her necklace. The Queen, the society lady’s newspaper, agreed with her, adding:

[Probably not] a woman in the land would mind missing just one of her gems for such a cause. It seems so little to give to those who give so much, and yet the price of one pearl may save a life; indeed the price of some of the pearls already given will save many lives.33

Like her husband’s newspaper success which relied on reaching all sections of society, not just a limited elite, Lady Northcliffe wanted her appeal to extend beyond the upper classes to include all women who wanted to give. She reminded her audience that it was not only the most perfect pearls that could hope to find a place in the necklace, there was room for smaller ones too, so that no one need hold back fearing her gift would be deemed unworthy.

Soon the Pearl Appeal was reaching far beyond the drawing rooms of Mayfair. Across the country, committees were set up to collect pearls; in the counties, the high sheriffs’ wives headed the appeal, in the cities the lady mayoresses took on the role. In Birmingham, the lady mayoress, Mrs Brooke, announced in the local paper that she was ‘at home’ at the Council House to receive pearls.

Although word of mouth was vitally important, what really made the difference was publicity. Thanks to Lady Northcliffe’s press connections, the Pearl Appeal reached a mass audience. Her husband threw the full weight of his newspapers behind her fundraising and over subsequent months stories about the pearls appeared in The Times and the Daily Mail several times a week. With The Times selling 131,000 copies a day and the Daily Mail being bought by 973,000 in 1918, public awareness of the Red Cross appeal soon spread across the country.34

Women from all walks of life, who were not part of high society, wanted to do their bit for the cause. Those who did not have pearl necklaces or could not afford to give a pearl individually were urged to give collectively. In response, one gem came ‘from a few ladies in County Galway’. It was suggested that collections for the purchase of a pearl should be organised among workers in munitions and aeroplane factories or in the mining districts. Soon, a fine orient pearl weighing 8.2 grains was sent in by the crew of an airship. The original idea had been to form a single rope of pearls, but the owners of the gems had other views and soon jewels were pouring in from across the country.

TWO

FAMOUS PEARLS

A picture of a society beauty, with her hair knotted in a simple chignon, her eyes cast down and wistfully looking away from the camera graced the cover of a March edition of The Queen. However, the focus of the photograph was not on the cover girl but on her large, luminous pearls which were perfectly set off by a gauzy white wrap draped discreetly across her shoulders. Under the chaste image, the caption read, ‘The Countess of Cromer, who is on the Committee of the Historical Pearl Necklace which will be sold for the Benefit of the Red Cross Funds.’1

The countess was a particularly appropriate figure to represent the appeal. Before her marriage known as Lady Ruby Elliot, one of the three daughters of the Earl of Minto, she had been made a Lady of Grace of the Order of St John of Jerusalem for her war work. The Pearl Appeal had become a family affair for Ruby, as her mother, the Countess of Minto, and her sister, Violet Astor, were also involved. The Minto family, like so many others, had paid a high price during the war. Both Violet’s husband, Charles Mercer Nairne, and the Minto girls’ brother, Esmond Elliot, had been killed. However, reflecting the idea that the pearls represented hope as well as loss, the countess’ serenity in the photograph was partly because she was pregnant. Already the mother of two daughters, in July she gave birth to her first son.

The cover was the ultimate endorsement from fashionable society. Inside this edition, The Queen captured the evocative element of the Pearl Appeal and the excitement it was creating:

If all pearls come to us with the moving mystery of romance about them, how immensely greater is this quality in the case of that wonderful Red Cross necklace – that necklace which is growing, pearl by pearl by pearl, in the service of those who are wounded in the fight for Britain, for Liberty, for Right. Strangely suitable are pearls to be the vehicle of mercy and of healing with their tender beauty, their mystic meaning, their almost spiritual loveliness: and how great is the need which these treasures will supply.2

The article was illustrated by a necklace made up of pearls interspersed with seed pearl-framed miniatures of royal donors and the symbols of the Red Cross and the Order of St John.

The royal family had led the way by giving the first pearls. Three generations offered their support: on 4 March, Queen Mary donated a fine jewel, and on subsequent days Queen Alexandra and Princess Mary also gave gems. Each of the royal ladies wore a different style of pearls.

Alexandra was the ‘Queen of Pearls’, from the moment the Danish princess married Bertie, Prince of Wales, in 1863 she became closely identified with the jewels. For her wedding, her family gave her the ‘Dagmar necklace’. Designed by the Copenhagen court jeweller Julius Dideriksen, the necklace was Byzantine in style, with pearl and diamond medallions set in ornate gold and diamond scrolls and swags. It was made from 118 pearls and 2,000 diamonds. The two large drop pearls came from the Danish royal collection and had been exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851.3 The necklace’s name came from the Dagmar Cross pendant, which is attached to it.

In the eleventh century, Queen Dagmar was the much-loved wife of the King of Denmark. When she died she was buried with a Byzantine cross on her breast and when her tomb was opened in 1690 the cross was removed and treated as a relic. It depicts Christ on one side and his crucifixion on the other. It became a tradition to give Danish princesses a copy of the cross when they were married. The replica, which was given to Alexandra, included within the pendant a piece of silk from the grave of King Canute and a sliver of wood which reputedly came from the True Cross. Weighted with history, the necklace was difficult to wear and Alexandra soon had it altered by Garrard. The jewellers made parts of the necklace detachable so that the cross could be worn separately, attached to a single strand of pearls, and the whole necklace could be worn as a stomacher.