Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

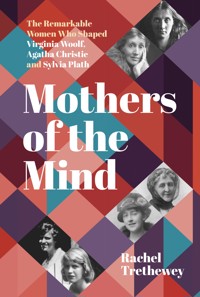

'These three portraits beautifully capture the variety and complexity of mother–daughter relationships.' - The Lady Virginia Woolf, Agatha Christie and Sylvia Plath are three of our most famous authors. This book tells in full the story of the remarkable mothers who shaped them. Julia Stephen, Clara Miller and Aurelia Plath were fascinating women in their own rights, and their relationships with their daughters were exceptional; they profoundly influenced the writers' lives, literature and attitude to feminism. Too often in the past Virginia, Agatha and Sylvia have been defined by their lovers – Mothers of the Mind redresses the balance by charting the complex, often contradictory, bond between mother and daughter. Drawing on sources from archives around the world and accounts from family and friends of the women, this book offers a fresh perspective on these iconic authors.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 641

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my Mum,

with Love.

Quotes from Virginia Woolf used by permission of The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf. The Society of Authors, 24 Bedford Row, London WC1R 4EH.

Quotes from The Hound of Death and Other Stories (‘Wireless’ and ‘The Last Séance’), Unfinished Portrait, Appointment with Death, Towards Zero, Death Comes as the End, Come, Tell Me How You Live, Ordeal by Innocence and An Autobiography. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd © 1933, 1934, 1938, 1944, 1945, 1946, 1958, 1977 Agatha Christie.

Quotes from ‘Ocean 1212-W’ in Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams, The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, The Journals of Sylvia Plath 1950-62, ‘Medusa’ in Collected Poems by Sylvia Plath, Letters Home. © Sylvia Plath. Used by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

Quotes from Letters Home by Sylvia Plath. © 1975 by Aurelia Schober Plath. Used by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd and HarperCollins Publishers.

Quote from The Journals of Sylvia Plath. © Sylvia Plath. Used by permission of Penguin Random House.

Quotes from Archive Material MS88993/1/1 from The British Library PER 3, Letters of Ted Hughes. © Ted Hughes. Used by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

First published 2023

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Rachel Trethewey, 2023, 2024

The right of Rachel Trethewey to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 202 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction

Part One: Julia and Virginia

1 The Dutiful Daughter

2 The Muse

3 The Perfect Match

4 A Meeting of Minds

5 The Absent Mother

6 The Hostess

7 The Angel Outside the House

8 The Martyr

9 The Family Falls Apart

10 An Abuse of Trust

11 The Rebellion

12 Haunting Virginia

13 Killing the Angel

Part Two: Clara and Agatha

14 The Poor Relation

15 The Wonderful Hero

16 The Homemaker

17 The Devoted Mother

18 Nightmares

19 The Widow

20 The Confidante

21 Literary Ambitions

22 Growing Apart

23 Agatha Finds Her Niche

24 Missing

25 Agatha’s New Life

26 Clara’s Literary Legacy

Part Three: Aurelia and Sylvia

27 The Outsider

28 The Genius Soulmate

29 Second Best

30 The Full-Time Homemaker

31 Daddy’s Girl

32 The Pact

33 The Teacher

34 Too Close for Comfort

35 Smith Girl

36 Crisis Point

37 A Transatlantic Relationship

38 Reunited

39 Rites of Passage

40 The Final Visit

41 Aurelia Answers Back

42 Aurelia’s Afterlife

Acknowledgements

Select Bibliography

Notes

Introduction

We think back through our mothers if we are women.1

When I first read this quotation from Virginia Woolf, as I was viewing an exhibition at the Tate of St Ives, its truth resonated with me. Seeing Virginia’s statement alongside a bewitching photograph of her mother, Julia Stephen, I was even more intrigued. As this mesmerising woman’s soulful eyes stared out at me from across the century’s divide, I wanted to find out who she was. She looked like Virginia, but there was also something elusive about her. I wanted to discover what she was really like and explore her relationship with her daughter.

As I thought about Virginia and Julia, I began to wonder whether the quotation was equally true for other female writers. I soon learnt that the Bloomsbury author was certainly not the only one who was moulded by her maternal heritage; Agatha Christie and Sylvia Plath were also inextricably entwined with their mothers, Clara Miller and Aurelia Plath. Their attitudes to life, literature and feminism were shaped by these formidable women. Virginia argued that not enough had been written about women’s relationships with each other and she was right;2 too often in the past, these authors have been defined by their relationships with their lovers rather than their formative affinity with their mothers. And yet, the maternal bond laid the foundation on which they built the rest of their lives, for good or ill.

There have been many previous biographies of Virginia, Agatha and Sylvia, but here for the first time Julia, Clara and Aurelia are put centre stage. They are the leading ladies, their daughters the supporting actresses and rather than just receiving a passing mention, their remarkable life stories are told in full. They deserve to be better known, as they were as passionate, complex, and at times contradictory, as their more famous daughters.

All three mothers were aspiring writers themselves, and by reading what they wrote, rather than just what was written about them, we hear their voices rather than just seeing them through the distorting lenses of other people’s eyes. Their voices need to be heard because they were always whispering in their daughters’ ears. Exploring their stories, we gain a new insight into the authors and why they developed in the way they did. The importance of these mothers should never be underestimated; Virginia admitted that for much of her life her mother obsessed her; even for three decades after her death, Julia haunted her every step. One Christie biographer portrays Clara as the love of Agatha’s life,3 while her daughter Rosalind described her grandmother as a dangerous woman because Agatha never thought she was wrong. A leading Plath scholar claims Sylvia and Aurelia were a team who worked together to achieve literary success.4 However, Sylvia’s psychiatrist encouraged the poet to believe that the mother–daughter relationship was at the root of her mental health problems and gave her permission to hate Aurelia.

Looking at the three writers through their mothers provides a new perspective on their lives and work. As a feminist icon, Virginia Woolf’s ideas about women’s roles can be seen as a rebellion against her anti-feminist mother. While Julia Stephen publicly campaigned against women having the vote, Virginia reacted by fighting for their rights in both the private and public sphere. For Virginia, the personal was political; her mother represented the ideal of Victorian womanhood, the self-sacrificing ‘angel in the house’ whom she had to ‘kill’ if she was to survive.

The most controversial moment in Agatha Christie’s life is her disappearance in 1926. Usually the break-up of her marriage is seen as the main reason for her breakdown, but was it just the catalyst while the underlying reason was the death of her beloved mother? The answer to this question depends on who was most important to her mental well-being – her husband or her mother? As Agatha’s grandson Mathew Prichard notes about the relationship between his grandmother and Clara, ‘The closeness with which they lived their lives is self-evident and much closer than the relationship I think most people have with their mothers.’5

Sylvia Plath biographies often focus on her passionate relationship with her husband, Ted Hughes, but her relationship with her mother was equally tempestuous. Aurelia Plath thought she had a close and loving bond with her daughter, but it was only after Sylvia’s death that she discovered what she really thought about her. It was devastating to find that the version of their relationship in Sylvia’s novel, poems and journals was so different from her affectionate letters home. In Mothers of the Mind Aurelia finally answers back and we learn what she really thought about the way her daughter treated her.

All six women were women who loved too much. They experienced what Agatha Christie described as ‘a dangerous intensity of affection’, meaning their love for their lovers and each other had the potential to destroy them. The bond between each of the mothers and daughters was uncanny, involving what Aurelia Plath called ‘psychic osmosis’, which allowed them to imagine themselves into each other’s minds. Being so close to another person could be claustrophobic and made it hard to establish a separate identity. In fact, the hyper-sensitivity, intensity, and imagination the daughters inherited from their mothers made them the outstanding writers they became. It gave their work an innate understanding of human relationships and an integrity which made each of the authors so successful in their different genres.6 Their sensitivity made them vulnerable, however, and each of the writers needed a great deal of mothering. When their parents were not there to provide protection, their lovers, friends and family stepped in to fill that role.

The mothers’ influence on their daughters’ writing was crucial. They were the first to recognise their child’s genius and then they did everything they could to help them fulfil that potential. The mothers were their daughters’ first teachers, readers and critics. For all three authors, their earliest experiments in writing were to please their mothers. Later, Clara and Aurelia encouraged their daughters to make the transition from amateur to professional writers.7 Once the daughters became famous authors, their mothers inspired some of their most compelling characters. As the people they knew best, all three writers wrote about them in both autobiographical and fictional forms. In her novel To the Lighthouse, Virginia recaptured the spirit of her mother in Mrs Ramsay. In Agatha’s fictionalised version of her early life, Unfinished Portrait, the character of Miriam is modelled on Clara. Less flatteringly, Sylvia’s unsympathetic portrayal of Mrs Greenwood in her novel The Bell Jar is based on Aurelia. In these works, the writers literally imagined themselves into their mothers’ minds, but as Aurelia later angrily explained, her daughter could only write what she thought her mother thought – her true feelings were very different. By finding out who the mothers really were, on their own terms, we discover how closely their daughters’ portrayals of them matched the reality.

Observing their family dynamics also helped to form their attitudes to feminism. In the Stephen, Miller and Plath households, lip service was paid to the dominance of men, but in each of the families a matriarchy, made up of generations of strong women, was really in charge. Both Virginia and Sylvia were critical of the sexist status quo which they believed turned their mothers into self-sacrificing martyrs. In contrast to the other authors, Agatha felt no desire to challenge her mother’s conventional role. Although she became one of the bestselling authors of all time, she was never a feminist.

The three authors wrote about their mothers and motherhood frequently in their novels, poetry, memoirs, letters and journals. Agatha Christie is best known for her detective stories, but she also wrote six novels under the pseudonym Mary Westmacott, which are very different from her usual genre. In these complex psychological studies, she explored family relationships in all their complicated forms. The Westmacott novels are windows into Agatha’s inner life, and they are examined for the insight they provide into Agatha’s attitude to the mother–daughter bond. Sylvia Plath’s most famous poems are about her father; who can forget the brutal portrayal of the Nazi in ‘Daddy’? However, this book is more interested in her poems about her mother; the pushy mother in ‘The Disquieting Muses’ and the life-smothering jellyfish in ‘Medusa’ are equally unforgettable and show how toxic her relationship with Aurelia had become.

The daughters provide only half the material, and they were not the only ones to leave fascinating written sources. Julia wrote children’s stories, essays and a book on nursing; Clara penned poems and short stories; Aurelia wrote poems, an academic thesis, and the introduction to her daughter’s Letters Home. Reading their mothers’ writing helps us to understand where the daughters’ talent came from. What was just a seed in one generation grew to fruition in the next.

This book is for admirers of Woolf, Christie and Plath, but it is also for anyone interested in mothers and daughters. Through three very different relationships, written about in separate but interrelating sections, we explore the maternal bond in all its diversity. We see both the positive effects of unconditional love and the negative repercussions of possessiveness. We discover how dangerous it can be to live vicariously through another person and explore how far a parent should interfere in their child’s life. These stories raise profound questions about how well we can ever know another person, even those we love best. Tracing each daughter’s journey through the painful rite of passage of separating from her mother and establishing her own identity, it ultimately shows that the emotional umbilical cord which ties us so tightly to our mothers is never completely severed, even by death.

Part One

Julia and Virginia

1

The Dutiful Daughter

One thing everyone always agreed on about Julia Jackson was that she was exceptionally beautiful. Her appearance was classical and austere, reminiscent of a marble Greek statue in its perfection. Her flawless features also conformed to the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic ideal of her era, making her allure both timeless and fashionable. Descended from a long line of beauties, Julia’s good looks were treated as her birth right and remarked upon wherever she went.

Born in India on 7 February 1846, like the other mothers in this book, Julia was an outsider, but for her it was a positive rather than a negative, adding an air of mystery to her many attractions. Part of the Anglo-Indian governing class, her mother’s family, the Pattles, were high-profile members of society in Calcutta and London, yet in both places they never quite belonged. In India they exuded French chic; when they returned to England, they brought the aromatic atmosphere of the sub-continent with them.

The family inspired many myths; there was no room for dull characters, everyone had to be larger than life, either a romantic hero or an outrageous villain. Although the reality was sometimes more prosaic, the romanticised versions reveal the colourful self-image the family cultivated.1 As she grew up, Julia identified with her French aristocratic ancestors; Virginia believed that her mother’s ‘wit and her bearing and her temper’ came from them.2

The most dashing figure in their ancestry was the Chevalier de L’Etang. Born at Versailles in 1757, Antoine Ambroise Pierre de L’Etang’s life was defined by his love for Marie Antoinette. According to family folklore, which may be more fantasy than fact, he was made her page when she first arrived in France from Austria. Spending time with the lonely young girl, he grew devoted to his royal mistress.3 After becoming an officer in Louis XVI’s Bodyguards, he was about to be created a marquis when rumours reached the king that Ambroise was the queen’s lover. In a fit of jealousy, Louis banished his rival to India. The chevalier’s departure from France saved his life because he was absent during the French Revolution. In India, he married Therese de L’Etang, who was part Bengali; the original family beauty, her lustrous hair and dark eyes passed down the generations.4 Although Ambroise created a fulfilling new life for himself in India, he never forgot his tragic queen. When he died, he was buried with the miniature of Marie Antoinette, resting on his heart.5

Less evocative but equally memorable was the story of Ambroise’s daughter Adeline and her husband, James Pattle, who became a judge in the Calcutta Court of Appeal. Recent research suggests he was a respectable public servant whose reputation was damaged by being unfairly confused with his notorious brother, but his family preferred the more dramatic version.6 His descendant Quentin Bell described him as ‘a quite extravagantly wicked man’, who was known as ‘the greatest liar in India’.7

James and Adeline had seven daughters including Julia’s mother, Maria. Educated in France, the Pattle sisters were high-spirited and unconventional, creating a stir wherever they went. Tall and graceful, Maria was quieter and more intellectual than her vivacious siblings. Known as ‘a blue-stocking’, in 1837 Maria married John Jackson, a well-respected physician.8 The couple started a family, but Maria took their two daughters, Adeline and Mary, to England for the sake of their health.

In 1845, Maria had just returned to India when a double tragedy struck. In September, her father, James, died having apparently drunk himself to death. According to one story, his corpse was preserved in a barrel of rum and sent back to England aboard a ship. During a storm, his body burst out of its container. The sight of her malevolent husband supposedly coming back to life so terrified his widow that she died of shock shortly afterwards and was buried at sea. An alternative version of the story had James’s remains being transported aboard a ship which then caught fire. When his body was consumed in the flames, the sailors said, ‘That Pattle had been such a scamp that the devil wouldn’t let him go out of India!’ Whatever the true story, the basic facts were tragic enough: both James and Adeline died within a few months of each other. Their devastated daughters recorded the tragedy on a memorial, stating that 52-year-old Adeline was ‘a victim to affliction and suffering produced by the calamity of her husband’s death’.9 The story was so memorably macabre it circulated in society for generations. Decades later, Virginia heard gossips say, ‘Oh the old Pattles! They’re always bursting out of their casks.’10

Julia was born a few months after this traumatic incident. Her first years were spent in Calcutta, living in a luxurious mansion, staffed by many servants.11 When Julia was 2 years old, Maria returned to England with her youngest daughter. Reunited with her two daughters Adeline and Mary, for several years Maria and her children lived with her sister and brother-in-law, Sara and Thoby Prinsep. Known for her ‘impulsive warmth’ and ‘restless energy’, Aunt Sara had inherited her vivacity from her French mother.12 Her husband, Thoby, was a calming influence among the excitable women in the family. A former director of the East India company and a Persian scholar, he became like a father to Julia.

When Julia was 5, Maria and her daughters moved to their own house in Hampstead. With her father still in India, Julia grew up in a matriarchy, where the women, not the men, mattered. In his frequent letters home, John Jackson comes across as an affectionate father, who missed his wife and daughters dreadfully. He sent them carefully thought out presents and wanted to be kept informed of all their news. He longed to be with them again, but his work continued to keep them apart.13

In 1855, Dr Jackson finally rejoined the family, and they moved to a larger house in Hendon. After the anticipation, it was an anti-climax and he made little impression on the female-dominated household. As Leslie Stephen, his future son-in-law, wrote, he became a ‘bit of an outsider’ and ‘somehow he did not seem to count – as fathers generally count in their family’.14 Although Maria respected her husband, she could not ‘ardently love’ him because he did not fit the Pattles’ romantic self-image. A passionate woman, who admired heroism, Mrs Jackson found little to inspire her in this affectionate, dutiful man.

As mother and daughters were exceptionally close, his exclusion from the charmed circle became particularly obvious to observers. Even Julia, who felt such a powerful love for the rest of her family, could only muster a lukewarm affection for him. This was partly because father and daughter had been separated for much of Julia’s childhood, but, according to Leslie, it was also because Dr Jackson was a ‘comparatively uninteresting character’.15 Admittedly, he was ill-at-ease in the intellectual and artistic circles his wife and daughters favoured, but he was a highly respected doctor.16 The denigration of this worthy medic passed down the generations, as his granddaughter Virginia described him as ‘a common place prosaic old man; boring people with his stories of a famous poison case in Calcutta; excluded from this poetical fairyland’.17

Maria created the ‘fairyland’ she craved elsewhere. She found a kindred spirit in the poet Coventry Patmore, who became a lifelong friend. His sentimental image of self-sacrificing femininity in his poem ‘The Angel in the House’ became the Victorian touchstone for what women were expected to be. Ironically, although Maria had rarely put her husband or anyone else first, she readily accepted these values, in theory if not in practice, and passed them on to her daughters who grew up to become models of saintly womanhood. Her inscribed copy of the poem from the poet passed down the generations from Julia to Virginia.18 The Bloomsbury author was to spend much of her life trying to escape from this limiting legacy.

Like many girls of her class and generation, Julia received only a limited education from a governess, which left her with ‘an instinctive, not a trained mind’.19 Valued for her beauty not her brains, she acquired the accomplishments expected of a Victorian wife; she spoke French with an excellent accent and played the piano well. Always a romantic, she read widely and developed a passion for De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater and Sir Walter Scott’s novels. As her later writing shows, she was highly literate and logical, but her own experience left her with a negative attitude to formal education for girls which was to have repercussions for her daughters.

From an early age, Julia’s striking good looks set her apart. Her mother did not want her to be spoilt by becoming too self-conscious about her appearance. Mrs Jackson had an irrational belief that every man who met her daughter, even fleetingly in a railway carriage, fell in love with her.20 When Julia went out, her older sister Mary was sent with her to distract her from noticing that people could not resist looking at her. Many sisters might have become jealous of such an attractive sibling, but Mary never resented her younger sister. Her protective instincts ran deep; even when Julia had become a mother herself, she still called her by her family nickname, ‘my darling Babe’.21 Perhaps there was no competition between the Jackson girls because there was a substantial age gap between Julia and her two older siblings. By the time Julia was grown up, her sisters were already married. In 1856, Adeline wed the Oxford History Professor Henry Halford Vaughan and six years later Mary married Herbert Fisher, tutor and private secretary to the Prince of Wales. Throughout their lives, Maria and her three daughters constantly exchanged gossipy, intimate letters sharing the minutiae of their lives. They trusted each other completely and knew this mutual understanding would never fail them.

Mrs Jackson was ‘passionately devoted’ to all her daughters, but Julia was ‘the cherished jewel of her mother’s home’.22 In a reversal of roles, as Maria became increasingly disabled from rheumatism, Julia cared for her. She nursed her mother when she was unable to get out of bed and accompanied her to spas on her quest for cures. At an early age, Julia learnt to put someone else’s needs before her own. Soothing her mother on her sickbed, she first discovered her lifetime’s vocation for nursing. This nurturing side of Julia was to become as fundamental to her image as her beauty. For the rest of her life, Maria totally depended on her self-sacrificing youngest daughter. She wrote to her sometimes three times a day and often sent an additional telegram to her ‘dear heart, her lamb’.23 Leslie Stephen wrote that there grew up between them ‘a specially tender relation; a love such as exceeded the ordinary love of mother and daughter and which became of the utmost importance to both of them’.24 A photograph of them together captures the dynamic: seated above her daughter with one hand resting on her cheek, Mrs Jackson looks gaunt and miserable while Julia leans into her mother, gazing up at her and looking concerned.

2

The Muse

Through her well-connected aunts, Julia was introduced to an exciting cultural world. Maria’s sisters were at the heart of Victorian society, counting the leading artists, writers and politicians of the age as personal friends. However, although they mixed with the elite, they never quite fitted in because they did not want to; confident in themselves, they had no desire to conform. Wearing cashmere shawls, chunky jewellery and silver bracelets and serving curry to their guests, the Pattles relished being different.1 While other women straitjacketed themselves in corsets and crinolines, they floated into a room in sweeping robes. Talking in Hindustani to each other or speaking English with French accents, they were a self-contained clan with their own set of values, which was humorously referred to as ‘Pattledom’.2

Their bewitching niece became the much-admired darling of their circle. Since being a child, Julia had spent a great deal of time with her Aunt Sara and Uncle Thoby at Little Holland House in Kensington. Years later, when Julia showed her children where it had been, it brought back the happiest memories; she ‘clapped her hands and cried, “That was where it was!” as if a fairyland had disappeared.’3

The Prinseps’ Sunday afternoon salons were legendary. Like the other writers in this book, Virginia imagined herself into her mother’s mind and wrote about her youthful experiences as if she was there. Virginia described Little Holland House as ‘a summer afternoon world’. At the centre of the melee was Julia, a cool, calm ‘vision’, standing silently with a dish of strawberries and cream.4 In To the Lighthouse, through Mrs Ramsay, the fictionalised version of her mother, Virginia imagines the impression Julia made on the young men she met. ‘Astonishingly beautiful’, she was absorbed in her own thoughts with her eyes downcast, looking ‘so still […] so young […] peaceful’.5

At Little Holland House, Julia was introduced to the Pre-Raphaelite artists. When Edward Burne-Jones became seriously ill, motherly Aunt Sara took him into her home and nursed him. Soon his fellow artist and sculptor G.F. Watts also moved in, setting up his studio on their upper floor. Nicknamed by the Pattles ‘Signor’, the sisters and their daughters provided him with the perfect models. Carrying a sketch book with him, he never missed an opportunity to draw them.6 When Julia was a child, Watts drew a head of her in chalk; he later did two more paintings of her, but she disliked one of them so much she refused to ever see it when it was exhibited. Shortly afterwards, the sculptor Pietro Marochetti used her as the model for Princess Elizabeth, the 14-year-old daughter of Charles I, who died at Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight. A teenage Julia posing as a dead princess set in stone her image as a tragic heroine.

Julia’s calm, often wistful, appearance personified the Pre-Raphaelite idea of beauty which was the height of fashion in her youth. As she embodied their other-worldly fantasies, these artists clamoured to capture her elusive essence. For a modern woman, there is something unsettling about their desire to portray her as a vulnerable victim. When Edward Burne-Jones painted her as the Princess Sabra being led to the dragon, she was once again turned into an icon of serene sacrifice – one who can only be saved by a chivalrous man.

Mrs Jackson began to have misgivings, worrying that Julia’s simplicity might be ruined by this homage to her beauty. When the sculptor Thomas Woolner asked if he could make a bust of her, his request was refused. The Pre-Raphaelite artists’ admiration for Julia was not purely professional; apparently, both William Holman Hunt and Thomas Woolner wanted to marry her. One of the leading religious painters of his day, Hunt met Julia through Little Holland House circles. In June 1864, he spent an enjoyable summer afternoon with Julia and her family at their Hendon home. It seems that it was at around this time that he proposed to her.7

Evidently, Hunt fell intensely in love with Julia; he was so devastated by her rejection that, even after a year, he could not bear to visit her home. When Mrs Jackson invited him to a party, he politely declined – writing that although he appreciated ‘the gentleness and kindness’ they all showed him during ‘the trying ordeal’, he could not risk coming. He explained, ‘I must not put myself in danger of suffering unnecessary bitterness now I feel at peace at last and I must be a wise man and take care to avoid sacrificing a state of mind which it took me so long to re-establish.’8 Despite his rejection, Hunt remained lifelong friends with Julia. He was attracted by her character as much as her looks and asked her to be godmother to his child. Like so many of her admirers, he regarded her with ‘reverence’, as if she were a saint instead of a real woman.9

Although the paintings of Julia were memorable, the series of photographs by Julia’s aunt, Mrs Cameron, came closest to capturing her essence. Impulsive and enthusiastic, Julia Margaret Cameron was the most talented of the Pattle sisters. When her daughter gave her a camera, she became obsessed by the new medium. Rejecting realism in favour of a more emotionally expressive approach, her innovative work revolutionised portrait photography. Taking the world’s first close-ups, she created intimacy and psychological intensity by suppressing detail and using soft focus and dramatic lighting.10

In 1860, Mrs Cameron moved to a house called ‘Dimbola’ at Freshwater, on the Isle of Wight. Like all the Pattle sisters, Mrs Cameron had a penchant for collecting and hero-worshipping great men, leading one visitor to exclaim, ‘Everybody is either a genius, or a poet, or a painter or peculiar in some way. Is there nobody commonplace?’11 Her neighbour, the poet laureate, Alfred, Lord Tennyson became a close friend and often visited with his illustrious guests.

Although Mrs Cameron photographed the most famous men of the era, Julia was her muse. There was a special bond between the two women because Julia had been named after her aunt who was also her godmother. Mrs Cameron’s photographs of her niece look surprisingly modern. Unlike most of her portraits of women, she depicted Julia as herself, rather than in costume as a religious or literary character. Usually, this approach was reserved for her male sitters, which suggests she recognised that Julia’s powerful personality made her any man’s equal.12 The haunting picture of Julia, hair streaming down her back, face half in shade, her eyes staring uncompromisingly at the camera as though she can see into a person’s soul, is unforgettable. When Mrs Cameron’s work was exhibited in London, the Evening Standard singled out for praise the ‘forcible likenesses’ of Julia over the portraits of Darwin, Longfellow, Tennyson and Carlyle.13

Mrs Cameron played a major role in creating Julia’s image as a great beauty. Without those mesmerising photographs, her good looks would have been ephemeral; her aunt made sure she would never be forgotten. Inevitably, with all this attention Julia could not avoid realising she was beautiful, but, according to Leslie Stephen, she did not have a shred of vanity. He wrote, ‘Nobody could have been more absolutely unspoilt and untouched by the slightest weakness of self-complacency.’14 However, Virginia believed there was a penalty for her mother’s beauty: ‘it came too readily, came too completely. It stilled life – froze it.’15 It made her seem aloof and untouchable. No doubt thinking of Julia, years later when writing her novel Jacob’s Room, Virginia described beauty as ‘important; it is an inheritance; one cannot ignore it. But it is a barrier, it is in fact rather a bore.’16

3

The Perfect Match

Looking at the images of Julia, even in her youth there is a sadness that underlies the beauty; she seemed very alone as though no one could reach her. Growing up in the world of Tennyson and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, her dreams were imbued with Arthurian legends where demure damsels patiently waited for courageous knights to awaken them from their somnolent state. For Julia, a young barrister called Herbert Duckworth was that gallant figure; he awoke in her the grand passion she had dreamt of.

Their love story conformed to her romantic vision. Herbert and Julia met in Venice in 1862. When Mary and Herbert Fisher were on honeymoon he was suddenly taken ill. The Jacksons rushed out to support Mary and, while there, Fisher introduced Julia to his university friend Herbert Duckworth. After their first encounter, they met again at Lake Lucerne and although they had only talked briefly, Julia was soon ‘head over heels in love with him’.1

Fourteen years her senior, Herbert was her perfect physical match; he was as handsome as she was beautiful. Tall and well-built, with broad shoulders and a generous, open face, he had high cheekbones, and a radiant smile which lit up a room. He epitomised the Victorian cult of the gentlemanly amateur, one who played the game for the sake of taking part rather than winning. He had been a good sportsman at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, without being excessively competitive. Similarly, he passed his examinations at university creditably without aiming for distinction. Much admired by his contemporaries, he measured up to their masculine ideal by being ‘the perfect type of the public-school man’.2

The son of a wealthy Somerset family, his ambitions were limited to practising as a barrister for a few years and then retiring to become a magistrate and country squire. His easy-going temperament was just what Julia needed; he diluted her intensity, chasing away her melancholy moods. Most importantly, unlike other suitors, it seems he treated her as a flesh and blood woman rather than a plaster saint on a pedestal. By doing so, he grounded her in this world rather than the next. She responded to him with a depth of passion and devotion which no other man had been able to unleash.

In February 1867, Julia and Herbert got engaged. Photographs of the couple taken at this time exude happiness. In a fashionable dress with ruffled sleeves and a miniscule nipped-in waist, Julia leans back with a serene but knowing look as though she was suppressing a smile. In his companion portrait, there is a glint in Herbert’s eyes; it looks as though he is about to say something amusing to his fiancée or burst out laughing. Dapper, with a boater on his lap and a large bow tie around his neck, he looks very pleased with himself. Certainly, many of the men in their circle considered him to be a particularly fortunate man, while some women thought Herbert ‘not hero enough for Miss Jackson’.3

Julia’s mother and sisters realised it was a rare love match. Mary Fisher described Herbert as ‘a beam of light […] like no one I have ever met’. This charismatic young man fitted perfectly into the Pattle mythology, visualising him as a Greek hero, the Great Achilles.4 As a serious young woman, Julia thought very carefully about what she was doing. When she made her vows, she gave herself unconditionally, body and soul. Believing their two lives had become one, she experienced ‘entire unity with him’.5

After the wedding in May, Julia and Herbert went on honeymoon abroad before setting up home in the Duckworths’ London town house in Bryanston Square. As Julia could not bear to be separated from her husband, unlike many young wives of barristers she joined him travelling around the Northern circuit. Living in lodgings, she entertained his admiring colleagues to tea and attended court to watch Herbert perform. However, her appearance proved to be rather a distraction. One barrister explained, ‘I spent the whole morning in court looking at a beautiful face.’6 Once Herbert was married, he became even less concerned about his career. In one letter he admitted that he was penitent for caring so little for his profession, but he was quite content with having such a wife.

For Julia and Herbert, they were each other’s world, they needed nothing else to complete their happiness. Yet, Julia’s perfect contentment came with a fear of losing it. If ever Herbert was late, she panicked that something had happened to him. When Julia was on a picnic with some friends, Herbert was delayed because he missed the train. She could not relax until he had arrived, pacing up and down the road near the railway station looking out for him in ‘a state of painful anxiety’ which seemed to her friends to be unreasonable. Her sister Mary recalled that she always got in such a state when she was apart from her husband. She told Mary, ‘I could not live if I had to be separated from him as much as you have to be separated from Herbert Fisher.’7

In March 1868, Julia and Herbert had their first child, George Herbert. Even with a baby, Julia still insisted on travelling with her husband on circuit. Herbert’s university friend and fellow barrister, Vernon Lushington, told his wife, Jane (who stayed at home with their small children), that Mrs Duckworth had ‘gallantly followed her husband’ first to Manchester and then Liverpool.8 In May 1869, the Duckworths had a daughter, Stella. Julia described this period in her life as a time of complete fulfilment. For four years she experienced ‘a full measure of the greatest happiness that can fall to the lot of a woman’.9

Later, Virginia wondered if her mother’s relationship with her first husband could really have been so perfect. She suspected that Julia romanticised it. Was Herbert really such a paragon? Virginia complained, ‘Youth and death shed a halo through which it is difficult to see a real face.’10 In her view, Herbert was so obviously Julia’s inferior in all ways that it was unlikely he could have permanently satisfied her ‘noble and genuine passions’. She wondered whether her mother just cloaked ‘his deficiencies in her own super abundance’, and made her marriage fit the narrative she had created. So far, Julia’s life had run smoothly. As Virginia wrote, she had ‘passed like a princess in a pageant from her supremely beautiful youth to marriage and motherhood without awakenment’.11

Julia soon experienced a rude awakening from which she would never completely recover. In May 1870, Herbert’s father wrote to Dr Jackson saying that he was concerned about his son’s health. He worried that a London life might be unsuitable for him. Mr Duckworth was considering increasing his allowance so that Herbert could give up work and live in the country. In September 1870, the Duckworths went to stay with Julia’s sister Adeline and her husband, Henry Vaughan, at Upton Castle in Pembrokeshire. Heavily pregnant, Julia was in the garden with Herbert when he stretched to pick a fig from a tree for her. As he reached up, he felt an acute pain; an undiagnosed abscess had burst. He deteriorated rapidly and within twenty-four hours he was dead aged only 37. Although this was the story passed down to Julia’s children, like so many of the family legends it may not be totally accurate. A contemporary newspaper article stated that Herbert sustained an internal rupture while carrying one of his children upstairs.12 Usually so scrupulously truthful, Julia preferred the more romantic version. Adding to the legend surrounding this tragic love story, after Herbert was laid to rest at his childhood home, Stella recalled that her distraught mother lay inconsolable upon his grave.13

Left a widow at the age of 24, Julia’s faith in fairy tales ended the day Herbert died. She never felt so happy again; from then on there was always a shadow and she saw life in stark terms as something to be endured rather than enjoyed. As well as the tragic human loss, she suffered from disillusionment. Stripped of her dreams, according to Virginia, she looked at the world with clear eyes, and became ‘more scornful than was just of its tragedy and stupidity’.14 Julia lost her religious faith, leaving her without the solace of believing she would be reunited with Herbert in an afterlife. Naturally, she turned to her mother in this crisis. After the bleak funeral, Julia and her children stayed with the Jacksons. As Mrs Jackson was so close to Julia, she felt it acutely, writing to a friend, ‘Our domestic happiness has been much troubled by our poor child’s irreparable loss. To us it was that of a son, so much did we love him.’15

Six weeks after Herbert’s death Julia gave birth prematurely to another son, Gerald. Having three children under the age of 4 just made her loss more poignant. Two-year-old George, who was the image of his father, kept asking, ‘Where’s Georgie’s Papa?’16 Photographs of Julia taken by Mrs Cameron at this time suggest Julia suffered from postnatal depression as well as grief. She appears unable to bond with her children. As she sits listless in a chair, looking into the distance, they cling on to her as though they are afraid of losing her too. Her arms lie languidly by her sides as if she does not even have the will to hold her baby. Always ethereal, she is spectral in these photographs, so thin that her bones show through her skin, and she looks in danger of literally fading away. Mrs Cameron recalled her niece’s large blue eyes filling with tears as she told her, ‘Oh aunt Julia, only pray God that I may die soon, that is what I most want.’17 She told a friend that she was ‘as unhappy as it is possible for a human being to be’.18

When Julia looked back on this time, she realised that she had suppressed her grief and tried to just carry on with life for the sake of her children, but this behaviour had been detrimental to her mental health. She later told Leslie that it ‘all seemed a shipwreck’. Her existence had become ‘a dream, a futile procession of images which seem to have in them no real life or meaning: the only real world is the world of intense gnawing pain which may be gradually dulled, but which refuses to admit any of the brighter realities from outside’.19

Her attempt to keep soldiering on after Herbert’s death was to be echoed in Aurelia Plath’s reaction to her husband’s death decades later. With three small children depending on her, Julia had no choice but to try to be cheerful by keeping busy and thinking as little as possible. But repressing her grief was damaging, she explained:

I got deadened. I had all along felt that if it had been possible for me to be myself, it would have been better for me individually; and that I could have got more real life out of the wreck if I had broken down more. But there was Baby to be thought of and everyone around me urging me to keep up, and I could never be alone which sometimes was such torture. So that by degrees I felt that though I was more cheerful and content than most people, I was more changed.20

A year after Herbert’s death, Julia moved into a house in London. Friends and family expected her to resume her old life as she was a very eligible young woman and her widowhood just added to her mystique. Her old admirers, including her flamboyant cousin, the artist Val Prinsep, were ready to comfort her. As Julia’s friend Jane Lushington wrote to her husband, ‘Mark my words – and don’t think me an unfeeling wicked monster – she will be Mrs Val Prinsep before she is thirty!’21 Even those closest to her underestimated the depth of her grief, however.

Julia had never been frivolous, but after Herbert’s death she became positively austere. She admitted that life in a convent appealed to her and, with her hair drawn back from her face and wearing severe clothes, she began to look like a nun. Her only real solace was helping others and during these years she found her vocation in caring for the poor and sick. She became ‘a kind of sister of mercy’, and her friends and family sent for her whenever there was illness or death. Yet even this relief came at considerable cost to herself because seeing such suffering reinforced her melancholy view of life. She admitted that she saw the world ‘clothed in drab’ and ‘shrouded in a crape-veil’. She felt most at home with the suffering and once she had rescued one person, she was looking for the next. As Leslie said, it seemed that she had ‘accepted sorrow as her life-long partner’.22

Although Virginia understood that the sudden shock had made Julia react as she did, like Sylvia Plath decades later, she was critical of her mother’s behaviour. Virginia wrote, ‘She reversed those natural instincts which were so strong in her of happiness and joy in a generous and abundant life, and pressed the bitterest fruit to her lips.’ Whereas before she had imagined herself as a romantic heroine, she now saw herself as a tragic one, someone who had looked into the abyss and was enlightened. According to Virginia, Julia believed she was free from all illusion and ‘possessed of the true secret of life at last’. It was a bleak realisation, however, for she saw ‘that sorrow is our lot, and at best we can but face it bravely’. 23

4

A Meeting of Minds

On a cold winter’s evening in November 1875, Julia visited her friend Minny Stephen, who was heavily pregnant. The two women had known each other since those carefree days at Little Holland House. During some of the darkest times in Julia’s widowhood, Minny’s warm-hearted elder sister, Anny, had encouraged her to take an interest in life. As Anny lived with the Stephens, Julia often visited her old friends. When Julia dropped in on that chilly night, she found Minny and her husband Leslie sitting harmoniously together ‘in perfect happiness and security’. Not wishing to intrude and thinking ‘the presence of a desolate widow incongruous’, she did not stay long and hurried home to ‘her own solitary hearth’.1

A few hours later, Minny went to bed in some discomfort. During the night she had a convulsion and never regained consciousness; by the middle of the following day she was dead. Her death had been as sudden and unexpected as Herbert’s. Like Julia five years before, Leslie Stephen was in complete shock, left reeling as in a matter of hours his secure world collapsed. Although their partnership was not as perfect as Julia and Herbert’s relationship, Leslie and Minny had enjoyed eight years of happy marriage. She had been the first woman to stir him out of his donnish ways.

The Stephen family were middle-class liberal intellectuals who had been at the forefront of reform for generations. Part of the Clapham Sect, they had campaigned against slavery. Leslie’s father, James Stephen, was one of the most influential colonial administrators of the nineteenth century. The Stephens’ circle formed an ‘aristocracy of intellect’, who felt secure in a sense of superiority based on moral and mental attributes, not wealth or birth.2 After being educated at Eton and Cambridge, Leslie became a tutor at his old university college. He looked set for an impressive academic career until a crisis of faith transformed his plans. To qualify for his position, he had to take religious orders, but he began to have doubts about the truth of the Bible. Unable to hide his scepticism, he resigned as a tutor at Trinity Hall.

In 1864, he moved to London and became a writer on several newspapers. Mixing in literary circles, he got to know Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, George Eliot and Anthony Trollope. Through mutual friends he was introduced to Thackeray’s daughters Anny and Minny. A great admirer of their father’s novel Vanity Fair, it was hardly surprising that the bookish bachelor fell in love with one of his favourite author’s daughters. Minny was attractive and full of fun with a playful sense of humour. She was not an intellectual, but her childlike simplicity and straightforwardness appealed to Leslie.3 When they sat next to each other at a dinner party in Hampstead, the attraction was obvious. A fellow guest, the novelist Mrs Gaskell, said afterwards that she foresaw they would marry.4

At the same time as Leslie was falling in love with Minny, he met Julia for the first time at a picnic. She was dressed in white with blue flowers in her hat and Leslie thought she was the most beautiful girl he had ever seen, like ‘the Sistine Madonna’.5 He did not speak to her, but he would never forget that vision. A few months later, Leslie became engaged to Minny; they married in June 1867, shortly after the Duckworths’ wedding. Occasionally, the two newly married couples’ paths crossed at dinner parties. When Julia was placed next to Leslie, she felt rather intimidated. He was known for being fiercely intellectual and opposed to anything fanciful, which he described as ‘humbug’, ‘sham’ or ‘sentimental’.6 Lacking confidence in her intellectual abilities, Julia feared he would be bored by her. In fact, he always admired and respected her, but at this time he was too wrapped up in his own life to give her much thought. He became known for the anti-conservatism of his writing. He attacked religion for encouraging intolerance and hypocrisy, and supported parliamentary and university reform as well as Irish independence and Church disestablishment.7

In 1870, the Stephens’ daughter, Laura, was born prematurely. Weighing less than three pounds at birth, she was a delicate baby. Although she was slow to teethe and speak, her mother did not realise there was anything seriously wrong.8 Minny devoted herself to being a full-time wife and mother. When she became pregnant again, five years later, the future looked promising, but all that changed in a matter of hours.

After Minny’s death, Leslie turned to the women in his circle to console him. The day after the tragedy, Julia came to support her old friend Anny. When she saw Leslie, she kissed him tenderly and asked him whether he had kept many letters because they were the greatest comfort. Her manner was too restrained for Anny’s taste; she would have preferred a greater outpouring of emotion, but that was not Julia’s way. She was used to helping the bereaved and knew the best support was practical not hysterical. A few days later, when Anny and Leslie went to Brighton, Julia took a lodging nearby to support them. Shortly after they returned to London, Leslie and his sister-in-law moved into a house next door to Julia’s home at Hyde Park Gate.9

Growing up with a devoted mother and doting sister, Leslie was used to women pampering him. When Minny died, he automatically expected her sister Anny to step into her shoes. However, Anny had other plans, and, to Leslie’s horror, she promptly fell in love with her much younger cousin, Richmond Ritchie. Seventeen years her junior, Richmond was a student while she was a mature woman of nearly 40. When Leslie walked into the drawing room and found the unconventional couple kissing, he was so appalled he gave Anny an ultimatum: she should make up her mind one way or another. His approach backfired and Anny got engaged that afternoon. She left her demanding brother-in-law to begin a new life with her youthful lover. Always a romantic, Julia encouraged the love affair and acted as peacemaker between Leslie and Anny, telling him he ‘ought to be glad of anything that increases happiness’.10

Once Anny was married, Julia stepped in to fill the gap. She became a sympathetic listener who gave good advice. Leslie was becoming increasingly worried about his daughter, Laura, who was displaying signs of emotional and behavioural difficulties. Julia and Leslie met frequently, and he began to depend on her judgement. The bond between them was based in their mutual grief; each felt there was someone who really understood. Julia was truthful with Leslie about her feelings for Herbert, and although his feelings for Minny were not so intense, his grief was fresher. What started as mutual consolation gradually developed into something more.

Leslie had always been attracted by Julia’s beauty, but now he became aware of her remarkable character too. Although initially Julia was not physically attracted to Leslie, she admired his intelligence and integrity. He suited the woman she had become. Their daughter Virginia believed that after Herbert’s death Julia began to exercise her mind more and now sought to satisfy her intellect.11 She admired Leslie’s essays before she fell in love with him. His writing about his agnosticism put into words her own sceptical attitude to Christianity. She was not looking for love; no one could replace the perfect Herbert, but the meeting of minds she experienced with Leslie made her feel less alone.

After a year, Leslie realised that he wanted to be more than just good friends with Julia. One day, walking past Knightsbridge Barracks, he suddenly had ‘a flash of revelation’, and said to himself, ‘I am in love with Julia.’12 As he faced his true feelings, he began to experience a sense of ‘joy and revival’.13 When she came to a dinner party, after all the other guests had left he gave her a note telling her that he loved her in the way a man loves the woman he would marry. He thought there was no hope of him being her lover, but he was desperate to remain her friend. Promising to do whatever she wanted and to never speak to her of love again if that was her wish, he hoped they could find a mutual understanding. After reading the note, Julia came to Leslie’s study and told him that although marriage was out of the question, they could be close friends.14

During the next year, they continued to see each other often, and when apart they wrote to each other daily. Julia invited Leslie to her aunt Julia Margaret Cameron’s house at Freshwater. Mrs Cameron was relieved to discover that he was not just a dry academic but had a poetic side too. Appealing to the Pattle romantic streak, he stood in the hall at ‘Dimbola’ reciting Swinburne’s Hymn to Proserpine and from the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.15 Afterwards, she wrote to her sister, Mrs Jackson, that she realised he was ‘not made of iron or stone as these Gods of pure intellect so often are’.16

Mrs Cameron believed that Leslie was Julia’s fate. She wrote to her niece that she believed his intellect ‘would unlock the closely barred doors of your heart’ and that love would flow from ‘that reverence which intellect and wisdom always inspire’. She did have some qualms as she detected a shadow around Leslie, and she believed this shadow waited for Julia. Observing Leslie’s ‘mournful manner’, as he sat very close to her niece ‘tall, wrapt in gloom, companionless, silent’, she knew his neediness would appeal to Julia’s nurturing nature.17

When Julia first introduced Leslie to her mother as her friend, Mrs Jackson was not impressed. He was rude about her hero, Coventry Patmore, telling her that he ‘despised’ the poet because he was ‘effeminate’ with ‘a cowardly view of the world’. Afterwards, Leslie had to apologise, blaming a fit of ‘temporary insanity’.18 Hardly surprisingly, at first Julia wanted to keep the importance of her relationship with Leslie secret from her mother. Knowing how possessive and protective Mrs Jackson was, Julia realised that she would interfere. Leslie urged Julia to tell her the truth. When Julia eventually confided, Mrs Jackson told her frankly that she did not believe their unconventional relationship could last. She thought her daughter should either give Leslie up or marry him. As always, Julia was very influenced by her mother and began to have concerns.

Throughout this time, Julia was honest with Leslie about her feelings. Her letters were loving but she still would not marry him. She continued to consider death would be the greatest blessing.19 She felt the situation was unfair for him because it made him restless, and it stopped him from finding a fulfilling relationship elsewhere.20 Leslie told her he would take her on whatever terms she wished, because he knew that he would love her for as long as he lived. Although they were not married, he believed they had become ‘one in spirit’.21

Reassuring her that whatever she decided he was there for her, he wrote, ‘Dearest, whether you marry me or not I will love you with all my heart, I will make it my whole purpose to give you […] such happiness as I can.’22 Assuring her that they were so emotionally in tune that he understood her without her needing to say anything, he signed off, ‘Goodbye, my own – for you are my own, are you not?’23

Finding love again seemed miraculous to them both. Julia felt ‘peaceful and sheltered’ with Leslie, but she was too afraid of loving and losing again to commit completely. There were moments when she was still overwhelmed by depression and believed she had little to offer him. She wrote:

Knowing what I am, it is no temptation to me to marry you from the thought that I should make your life happier or brighter – I don’t think I should […] All this sounds cold and horrid – but you know I do love you with my whole heart – only it seems such a poor dead heart. I cannot tell you that it can never revive, for I could not have thought it possible that I should have felt for anyone what I feel for you.24

Recognising this as a step forward, Leslie replied that this was enough for him. But Mrs Jackson was right; this unsettling state could not last forever. As Leslie needed someone to manage his household, he decided to employ a German housekeeper. Julia realised that this might set the seal on the terms of their relationship. During a Christmas visit to her mother, she agonised about what to do. When she told Leslie that she feared having another woman in the house would come between them, he once again assured her that ‘you have got me so fast that you can do with me whatever you like’.25 Leslie’s patience and understanding paid off. On Julia’s return to London, he spent the evening with her. Sitting in her armchair by the fire, she finally told him, ‘I will be your wife and will do my best to be a good wife to you.’26 Leslie was ecstatic, telling her that it was a ‘marvellous thing’ and that she was ‘making sunshine and peace for me’. He recognised that they would have to face sorrows as well as joy together but told her, ‘If I can see your face as I have seen it sometimes lately, I shall think that I have been one of the happiest of men.’27

Once her decision was made, Julia’s doubts vanished, and she wondered why she hesitated for so long. In a letter to a friend, she wrote, ‘I had thought that no such brightness could ever have come to me, but it has.’28