Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Bedford Square Publishers

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

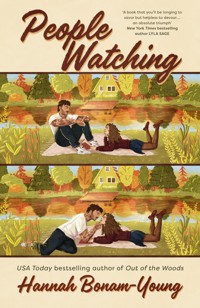

The instant New York Times Top 5 bestseller! 'I blew through this! Bonam-Young blends gritty reality, family, and passion to create a powerful story about acceptance and the power of opening up to love. I loved this'—Abby Jimenez, #1 New York Times bestselling author Introducing Prue and Milo in the brand new heart-warming and spicy strangers-to-lovers romcom and the start of a new duet from bestselling TikTok author Hannah Bonam-Young! Prudence Welch has always valued her introverted lifestyle in the small town of Baysville, Ontario. She is content with working at her father's gas station, writing her beloved poetry, and caring for her mother who has been diagnosed with early onset Alzheimers. Despite her father's continuous remarks that she should venture out of the town to have a more fulfilling life, Prue just can't leave it behind. Milo Kablukov is a free spirit, who has had his fair share of worldwide adventures and wild nights. But when he is called by his brother for an urgent family matter in Baysville, he finds that he just might have to stay put a while. After an intriguing encounter with Prue, Milo sets his sights on getting to know her, but he finds that a friendship with Prue may be different to what he had been expecting...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 476

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JOIN OUR COMMUNITY!

Sign up for all the latest news and exclusive offers.

BEDFORDSQUAREPUBLISHERS.CO.UK

Praise for Hannah Bonam-Young

‘Warm, sexy, and vulnerable… Hannah Bonam-Young needs to be on your romance radar’

Hannah Grace, author of Icebreaker on Next to You

‘Funny and huge-hearted and romantic and real’

Talia Hibbert, author of Get a Life, Chloe Brown on Next of Kin

‘Tender, thoughtful, and deeply touching’

Chloe Liese, author of Two Wrongs Make a Right on Next of Kin

‘Phenomenal, adorable, sexy and romantic, hilarious, gasp-inducing! I will never be over it!’

Clare Gilmore, author of Love Interest on Next to You

‘You know when you read a book and it feels like there’s a fist around your heart and your stomach drops and your throat goes tight? Everyone needs to pay attention. Hannah is going to do incredible things’

B.K. Borison, author of Lovelight Farms on Out on a Limb

‘Absolute, utter perfection’

Chloe Liese, author of Only When It’s Us on Out of the Woods

‘I had the time of my life’

B.K. Borison, author of Lovelight Farms on Out of the Woods

People

Watching

Hannah Bonam-Young

For all of you who have spent your time waiting, watching, and hoping.

Your time will come. All will be well.

Contents

Cover

Praise for Hannah Bonam-Young

Title Page

Dedication

Author’s Note

One: Milo

Two: Prue

Three: Milo

Four: Milo

Five: Prue

Six: Milo

Seven: Prue

Eight: Milo

Nine: Milo

Ten: Prue

Eleven: Milo

Twelve: Prue

Thirteen: Milo

Fourteen: Prue

Fifteen: Milo

Sixteen: Prue

Seventeen: Milo

Eighteen: Prue

Nineteen: Prue

Twenty: Milo

Twenty-One: Prue

Twenty-Two: Milo

Twenty-Three: Prue

Twenty-Four: Milo

Twenty-Five: Prue

Twenty-Six: Milo

Twenty-Seven: Prue

Twenty-Eight: Milo

Twenty-Nine: Prue

Thirty: Milo

Epilogue: Milo

Acknowledgments

Also by Hannah Bonam-Young

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE

HELLO AGAIN, FRIENDS. I hope you’re well.

I am so very excited to share Milo and Prue’s story with you all. I know we’re not supposed to have favorites, but if I did . . .

This book is set in the small town of Baysville in Muskoka, Ontario, which my husband’s family has visited and made memories in for decades. When I think of Baysville, I think of the first time I got to visit in 2011. I was invited to spend a week at their cottage by my husband’s sibling, who didn’t know about the debilitating crush I had on their older brother. I remember the giddy, exciting feeling of sitting next to him for the first time, the tempting way his hand rested on his knee and wondering whether it would be totally crazy to reach out and hold it. I cringe at the memory of how I rolled my eyes when my future mother-in-law attempted to play wingman for us, even though I loved her for it.

Baysville is probably not the most romantic place to some, but to me, it is. It held the first sparks of what is now the greatest love story of my life. It’s where we went year after year, spending long, lazy days on the dock soaking in the sun, rainy days cuddled up under blankets next to the fireplace, and sneaking in make-out sessions when his parents weren’t looking. Now, it’s where we bring our kids. We play in the pool that wasn’t there when I first joined the family, we push the kids on swings we never took much notice of before they were born, and we walk into town to get ice cream, as we’ve always done.

Baysville is our happy place.

With all that said, this book is a very loose representation of Baysville. I hoped to capture the essence of this incredible little town rather than stay true to the layout, shops, local folks, etc. So, while reading, think of it as inspiration and my personal way of honoring a place that means so much to me rather than an accurate depiction. I thought about changing the name, or about making up something else entirely, but it didn’t feel right. However, there are some things that Baysvillians and some visitors to the area will pick up on.

That above paragraph of the author’s note is for my beloved father-in-law, the town’s historian. Don’t be mad at me, Dad, I did read the pamphlets about Baysville you gave me. Next time we’re at Nellie’s, the ice cream is on me.

Then, there’s the other matter at hand, the one I’ve been dreading talking about—Prue’s mother, Julia, and her Alzheimer’s diagnosis. If you’ve been on my writing journey with me for a while, you might know about my grandmother Lorraine and the impact she’s had on my life. I’m not shy to say that my grandma was my favorite person. She was brilliant. A powerhouse of a woman with unmatched intelligence, and unwavering faith and loyalty, who also somehow always had the perfect snarky remark at the ready. She made me feel safe, loved, and seen during many of the times that I felt impossible to know, love, or protect.

So, when my brilliant, brilliant grandmother began losing her memory, began losing herself, it felt unthinkable. She was too bright of a light to be dimmed, I’d thought. It was heartbreaking in a way I hadn’t known was possible.

Still, I will never regret the time I spent caring for her. I had the opportunity to return some of that same safety, love, and understanding that she’d given me throughout my childhood back to her. And while it was often difficult, and while I was not as good at caring for her as she had been for me, I look back with unwavering gratitude on that time we had together.

I treasure each time her face lit up in recognition of me or another loved one. I still feel her trembling hand in mine when she told me she was so glad I could visit, for the tenth time in a row while sitting with her in our shared home. I still smile when I recall the bittersweet memories of her checking the mail six times in one day, waiting on a love letter from her long-departed husband.

I still don’t really know how to process the grief I feel from losing her. The way my heart reaches for hers so often, knowing she’s no longer here, knowing she was hard to reach long before she was gone. At the same time, I can recognize how frustrating it must have been for her, how much she grieved the loss of her once sharp mind and wit, and how that made her eager to move on to what she believed God had in store for her in the next life.

Regardless, I miss her terribly and I hope that I can honor her in this way.

Because this love story isn’t just about Prue and Milo—though their love story is one of my favorites. It’s also about a love between Prue and her mother and the lengths we will go to for the people we care about most.

I hope you enjoy your time in Baysville, dear reader.

Love,

HANNAH

CONTENT WARNINGS:

• Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease

• Caretaking for an ill parent

• Depictions of struggling as the result of childhood abuse from parents (past, off page, no reappearance or amends)

• Descriptive sexual content

• Brief mention of high-risk pregnancy and early labor

• References to smoking cigarettes and alcohol consumption

• Cancer diagnosis

You drove into town on a windy day.

A tempestuous welcome turned to a soft breeze, then to a contented sigh.

Relief from all that surrounds us, billowing sheets on the line.

“Finally,” the wind blew, “now the rest is up to them.”

—P.W.

ONE

Milo

“PLEASE, BERTHA, BABY, I am begging you,” I say, tightening my hands around the shuddering steering wheel. There’s not another living soul in sight. No one to witness our inevitable crash and burn if Bertha decides to call it quits and send us rolling backward down the hill. On this Muskoka back road it’s just me, Bertha, the black tar pavement under us, the gray storm clouds above us, the granite outcropping bordering either side of the road, and, as always, the bobblehead Jesus on my dash.

“I swear to everything good and holy that if you make it over this hill, I’ll never ask you for anything ever again.” She sputters, and I grit my teeth waiting for the backward roll. “If we make it to town,” I plead, each syllable equal parts pathetic and desperate, “I’ll fill you up with premium fuel and let you rest for a week.” The tires jolt, forcing my hands on the wheel to fight for control. “Okay, okay! Two weeks. I promise.”

My beloved van’s speedometer is broken, as is most of her, but the temperature gauge isn’t, unfortunately. The needle is fluctuating between you’re beyond fucked and are you on fire yet?

“C’mon, old girl, don’t quit on me now. Not yet. Don’t you want to go home again?” Though I cannot help but think that my death would probably save me from this familial obligation. Maybe Bertha is taking care of me, just as she has for the past decade, and death is the lesser of these two evils.

The sound of metal grinding against metal, an irritating high-pitched squealing, is her answer. Then, the choking of an engine, like the mechanical equivalent of a smoker’s cough, which is never a good sign. I prepare my final words, taking a deep breath as the car slows to a stop a few feet shy of the top of the hill.

Well, this is it, I think to myself. I wonder what my obituary will read, if anyone bothers to write one. If it was up to me it would say: Milo Kablukov, 28, was a nomadic slut, childhood sheep farmer, and wannabe artist with a heart of gold and a penis that launched a thousand ships.

Just as I’m about to say my final goodbyes to this mortal plane, Bertha kicks back to life, taking us over the edge of the hilltop and onto flattened road. I open my eyes, having closed them while bracing for disaster.

“Whew, baby!” I shake my limbs free of tension as I adjust position in my seat and toss back my hair. “You little tease,” I say, petting the dashboard. I make a turn onto a back road toward the train station with a flat palm on the wheel and slow my speed to give Bertha a rest. “You really had my heart racing that time, gorgeous,” I tell her, releasing the last of my tension in a languid breath.

Other than my younger sister, Nadia, Bertha has been the only consistent woman in my life since I got the fuck out of my hometown of Dorset, Ontario, the day after my eighteenth birthday. The town slogan, if it were up to me, would be: Dorset: Where the sheep outnumber the people.

I won’t be returning there any time soon. My brother, my summoner, has set up home a few towns over. Somewhere just as boring, no doubt, but far enough away from Sonia and Andrei Kablukov—good old Mom and Pop—that my brother would even dare to ask Nadia and me to come to his rescue.

I pull up in front of the small white building that is technically a train station but looks more like an old cottage. “There she is!” I shout as I wheel the passenger window all the way down. “Nadia motherfuckin’ Kablukov in the flesh!”

My sister, who perpetually chews gum on one side of her mouth, smirks as she rolls her eyes. “You’re late.” She leans into the window, tapping the inside of the passenger door. “Hi, Bertha baby, you’re looking as shitty as ever.”

“You look older again,” I point out, scowling at her. “You should really stop doing that.”

“Aging?” she clarifies.

I nod.

“Charming . . .” She assesses me, or at least what she can see of me from the window, with a curious, wry grin.

I look her over too, in the habitual, almost subconscious way I always have. Searching for the scrapes, burns, and bruises, and hoping to find none. Nadia has always been equal parts stubborn and prideful, discontent to be the youngest of us three siblings. Which meant she got hurt trying to do things above her paygrade a lot.

At four, she tried to make her own breakfast, and I helped ice the burn from her run-in with the frying pan. At nine, she climbed up to the roof to fix the TV antenna, and I fixed the eaves trough she broke on her way down and bandaged up her ankle. At twelve, she tried to teach herself to drive Dad’s tractor, and I mended the broken fence and her hand from the splinter she’d gotten trying to repair it herself. Then, there were all the many nights that she’d sneak into my room when Mom and Dad were screaming at each other, and I’d let her pretend it was for my sake, not hers.

Now, instead of looking for scraped-up limbs, I look at her eyes. I try to judge how much weight they’re holding. I attempt to measure the dark circles underneath as if they were rings on a tree stump, as if age and sleepless nights could be measured in the same way.

Nadia’s hair is back to its original black color and rests just above her jaw in a straight, sharp line. She’s gained some weight back, which I’m relieved to notice, but not enough. She was way, way too thin for a while there. She joked that she was too busy to eat all the while finding the time to smoke her way through a pack of cigarettes a day.

I’m not judging—all three of us siblings have our vices, our own unhealthy way of surviving our fucked-up childhood—I just hated seeing her look weak when she is far, far from it.

So maybe it’s her hair, or the extra few pounds she’s gained back, or the fewer rings under her eyes, or the less jittery way that she stands on the curb allowing me the chance to look her over—but she does look older. It settles me and somehow makes me uneasy at the same time. She’s doing better, but I didn’t know that until now. And when was the last time I had asked my little sister how life was treating her?

I need to be better at asking.

“You look great, зайка.” Зайка, or bunny in Russian, is what Nik, our older brother, started calling Nadia from birth. She had these huge, chubby cheeks as a baby that reminded him of his favorite animal at the time; the ones he’d sneak food to that lived under my parents’ barn. “You just look different, that’s all.”

“Well . . . You were gone a long time. Again,” she replies, quirking an arched brow.

I unbuckle the seatbelt, but don’t turn off the engine before getting out of the driver’s seat. Truthfully, I don’t know if I could get Bertha to start back up again and there’s no way I could afford to get a tow truck.

“Get over here,” I request, opening my arms wide for her as I approach. Nadia, stiff as a board, welcomes my hug in a literal sense by stepping toward me, but keeps her arms firmly at her sides. “I missed you,” I say over the top of her head. She mumbles something that sounds like uh-huh into my chest. I squeeze tighter before releasing her.

I reach toward the ground for one of her oversized khaki duffel bags. “What’s in here?” I say, throwing it over my shoulder before reaching for the other one. “This has to be at least fifty pounds.” I pick up the second bag. “Each!”

“That, dear brother, is everything I own. Minus the lamp that came with my apartment, which is somehow controlled by the upstairs tenant. Or, at least, I hope that’s who is turning it on and off all day.”

I walk toward the back of the van, and she follows closely. “Toronto sounds . . . fun.”

“For sure.” I catch her smiling softly at the back doors of the van as I struggle to open the right rear door. Much like my own skin, Bertha’s outer shell is covered in memories, mistakes, and inspirational scribblings. “I see you’re still collecting these . . .” She taps on a bumper sticker, one of many, then underlines the words with her finger. “My other ride is your mother,” she reads, firing an entirely unconvincing disapproving stare my way. “Real classy.”

I smile widely at her in response, flashing all my teeth as I manage to pry open the door with a grunt of effort. “I have the father version of that one too,” I say, gesturing to the hundreds of other stickers decorating the entire surface of the doors. I toss her bags into the hollow back of the van, alongside my own luggage. “I believe in equality, after all.”

“Do you? Or are you simply an equal opportunist?” she asks, smirking.

My bisexuality is no secret to either of my siblings and, as much as they like to tease me about it, they’ve been nothing but supportive. Not that they’d have a choice to be anything but. I have no place in my life for bullshit from anyone, family or not, and they know that. “Can’t it be both?” I ask, shutting the door by throwing my shoulder against it.

She nods, grinning mischievously as she pulls out her phone from her pocket and snaps a photo of Bertha’s rear. “So . . .” I lean my shoulder against the door and run one hand through my hair, pushing it to one side as a gust of wind tries to blow it back. “What do you make of all this?” I gesture broadly in what may or may not be the direction of Baysville, my brother’s new home. “A bit dramatic, don’t ya think?”

Nadia’s lips pout as she considers my question, then she looks up at me with those deep brown eyes that all of us siblings have. “You mean Nik using his one-one-nine?”

We coined the term one-one-nine over twenty years ago. Whereas a code nine-one-one meant an emergency that we, unfortunately, had no choice but to involve our parents in, a one-one-nine could and should remain between us siblings.

Nik graciously granted us all two one-one-nine uses per year in childhood. But the rule was that we’d have only one after the age of eighteen to use in perpetuity. That goes for all of us. We have one Get Out of Jail Free card. One Hail Mary. One help-me-bury-the-body-and-don’t-ask-questions. Then, you’re on your own.

“Yeah,” I answer. “It feels a bit extreme; don’t you think? He’s dreamed of opening his brewery for years and we’ve never been a part of that plan. What could possibly constitute an emergency?”

“He never specified it had to be used in an emergency. . . . And, if I recall correctly, you used yours to make me catch a mouse for you when we were backpacking in Costa Rica.” She leans her hip up against the van and digs around in her oversized tote for what I hope is not a cigarette. “So, maybe let’s not be so quick to judge.”

“It was Ecuador,” I correct her, “and it was a rat, not a mouse. Plus, you said we didn’t have to count that because a one-one-nine is only for situations that require both siblings, and Nik was here playing house. I’m saving mine for my forties, when I plan to hit rock bottom.”

“That doesn’t sound like something I’d say,” Nadia replies as she continues rifling through her bag. “And Nik wasn’t playing house, he’d fucking committed to the bit. But I guess you’d already skipped town by the time he got Sef knocked up and married her a month later. . . .”

I’d been gone for only three months when my brother popped the question. I couldn’t go back for the wedding. I just . . . couldn’t. I could finally breathe, lost in the middle of nowhere. I finally felt some semblance of freedom, some control over my own life. Still, I know Nik hates me just a little for not showing up. And, I hate myself a little for it too.

Nadia’s arm is deep enough inside of this tote bag of hers that she should consider asking it if it has a safe word. “All right, what’re you looking for in there?” And please don’t say a cigarette.

She rolls her eyes, again. “Relax, I quit. . . .”

“Okay, good.” Wait; how did she? “Wait, I didn’t—”

“Aha!” she says, pulling out a neatly folded lined piece of paper. “Here,” she says, handing it to me.

I unfold it, and immediately recognize my handwriting and half-scribbled signature at the bottom of the page, though I don’t remember writing any of it. To be fair, Nadia and I don’t typically stay sober for very long when in each other’s company.

“I, Milo Kablukov, hereby grant Nadia Kablukov the right to one pack of cigarettes whenever she is within a twenty-mile radius of either of our parents.” I look up, noticing that she’d mouthed the words along with me as I’d read them. “Furthermore, I will purchase them for her without complaint. Signed on the fifteenth of May, 2022 . . .” We say that last part in unison.

I scrunch it up into a ball in my fist. “Didn’t you just say you quit? Won’t this, like, fuck that up?”

“I’m not going to smoke them!” she says, rolling her eyes, then they harden as she purses her lips. “Unless we end up seeing Mom and Dad. Then, all bets are off.”

I sigh, tossing the paper back and forth between my hands. “Nik said they haven’t come by his new place at all. That we probably won’t—”

“I know.” She rips the balled-up note away from me and begins smoothing it out. “I asked him too.”

“Fine,” I say, turning to walk toward the driver’s seat. “But you can never smoke inside of Bertha. She’s got asthma,” I shout over the top of the van. Plus, I’m not fully confident she won’t somehow combust if we light a match in her. She does have a slight gasoline-tank-leaking smell.

We both get inside, fasten our seatbelts, and reach out to pat the bobblehead Jesus. Nik bought him for me ten years ago as a gag gift the day I bought Bertha from his best friend’s grandma, her namesake. None of us siblings are remotely religious, but we are creatures of habit, and I can no longer drive without first forcing all passengers to pay their respects to bobblehead Jesus.

“I seriously cannot believe that Bertha’s still going.” Nadia looks around cautiously. “How old is she now?”

“You know better than to ask a lady’s age.” I think back to the hill, my obituary, and then to the memory of my little sister ten years younger than she currently is, sitting in the passenger seat, asking me for the last time to not leave town. I decide then to take the long way to Nik’s new place, avoiding any hills, highways, or possible dangers. I’m more than willing to roll the dice with my own life, but not hers.

“But seriously, is she still safe to drive?”

“Why? You worried about me, Nads?” I ask, winking at her.

In a totally unexpected move from the invulnerable youngest Kablukov sibling, she nods.

I cut the teasing and go for sincerity. “She nearly quits on me every day, but I like to think of that as her way of flirting.” I push down on the gearshift so it doesn’t pop out of place, and attempt to shift the van from park into drive as Nadia braces herself with one hand on the grip handle above the door and the other on the dash.

“Flirting with death, maybe.” She turns toward me as the engine purrs, and we begin rolling backward slowly, toward the sunken edge of the parking lot. “Your attachment to this van will get you killed,” she says, looking anxiously at the back windshield.

I fight to get Bertha out of neutral, and then put my foot on the pedal, driving us away from the small station. “Nah, that’s not the way I plan to go.”

She sighs. “Dare I ask?”

“I’m going out in a blaze of glory on my sixty-ninth birthday. My vision is a crowd of naked people cheering me on as I attempt to jump a motorcycle between cliffs, but instead, I plummet to the shark-infested waters below.”

“Sounds about right.” She pauses to pinch her temples. “I’m happy to hear that you’ve got life goals, I guess”—her head tilts sharply—“or would that be death goals?” she whispers.

I ignore her. “I, of course, survive the fall and fight off the sharks,” I add, making a right turn onto the main strip of road that connects most of the small towns around here.

“Naturally.” Nadia pokes at a button for the radio, clearly trying to shut me up, but nothing plays. Joke’s on her—the radio hasn’t worked for at least three years now. There is a tape stuck in there that plays only one song, and you have to hit all the buttons in a certain sequence to get it to work. I will not be teaching her. She will have to endure the ramblings of her favorite brother instead.

“I’m taken to the hospital, naturally, for my minor injuries. . . .”

“Sure.” She turns the volume dial, then hits the cassette slot with the heel of her palm. “At what point in this story do you actually die?”

“Give me a second!” I slap her hand away from the buttons on the dash. “Eventually, one of the nurses hears the tale of my heroism and, tragically, he or they or she rides me so hard in my hospital bed that my heart gives out.”

She recoils, putting space between us as she leans toward the passenger door and shoots daggers at me with her eyes.

“No?” I ask. “I thought that was the perfect plan.”

“What is—and please feel free to really dig deep here before you answer—wrong with you?”

“Fuck, sorry for having aspirations!” I take my eyes off the road for only a second to smile at her. Nadia’s arms are crossed as she leans back in her seat, enraptured by the view out the window of the storm clouds gathering above us. I allow the silence for a minute, maybe even two, before I can no longer stand it. “So . . .” I drum my thumbs on the steering wheel. “Want to catch me up?”

“On?”

“Your life.”

“Do I have to?”

Yes. “Do you have a boyfriend?”

Her jaw tightens, but she still answers through gritted teeth. “No.”

“Girlfriend?”

She chuckles, kind of—it’s more like a scoff. “No; still straight.”

“God, you and Nik are so boring! Bisexuality is the way of the future. . . .”

“You are the agenda that Fox News is always blathering on about.”

That makes us both smile, which sends a rush of relief through my veins. “Which part of the city are you living in? Do you like it?”

“A shitty month-to-month apartment with the aforementioned haunted lamp in Moss Park. I gave up my lease to come here, though.”

“Career?”

She laughs dryly.

“Okay, but a job?” I ask.

“I was bartending for a bit but, again, I quit it for this.”

I turn to her, attempting to keep my eyes on the road as I communicate my clear surprise. “You, Nadia Annika Kablukov, were in a customer service position?”

“I know.” She giggles darkly, flashing her eyes at me. “Admittedly, I didn’t make tips. But!” She perks up, straightening in her seat. “My bar did have this drink called the Hurricane where dudes would pay me to pour a shot into their mouth, make them swallow it, then throw water at them before slapping them across the face.”

“Okay, now I’m seeing the appeal. That sounds like your dream come true.”

She sighs wistfully, placing a hand on her chest. “It was.”

“Anything else of note?” I ask. “Tell me something Nik or Sef don’t know so I can hold it over them.”

She leans her head toward the window as she thinks it over. I hate that it’s difficult. That Nik is probably checking in with her as often as he checks in with me. Except Nadia probably responds . . . unlike me. “I almost adopted a cat,” she offers.

“No shit, really? What happened?”

“He was living on my fire escape and screaming every night, so I started feeding him. Mostly just to get some sleep at first, but then I stupidly got attached to the thing. He looked like he had fleas, so I didn’t want to let him inside without getting him checked out first. . . .” Her voice trails off.

“Okay, then what?” I ask, slowing to a stop as we approach a red light.

“I took him to the local animal shelter and they found one of those microchips in his ear. Turns out, he’d run away from home.” She pauses to throw a playful smirk my way—as if to say You’d know something about that. “His owner had never stopped looking for him, I guess. He got picked up later that day.” Her voice softens, almost as if she’s . . . feeling.

This is new territory for Nadia and me. I’ve got no problem confessing my sentiments, sins, and secrets to whomever is spending the night in my bed, but my family did not do feelings growing up, let alone express them to one another. “I’m sorry you couldn’t keep him, зайка.”

She makes a dismissive noise, akin to a cleared throat. “It’s probably for the best. I wasn’t ready for that level of commitment.”

I chuckle, thinking of the sad pair we are in comparison to our family-man big brother who craved commitment and steadiness from birth. “Fair enough.”

She shrugs it off. “How about you? Where have you been?”

“I was following a carnival around Texas for a while. I drew caricatures next to the ring-toss game. Sometimes they’d let me play for free when it was slow.”

“I’m proud of you for maintaining your artistic integrity.”

“All right, well, I’m a big boy, Nads.” I pat my stomach, keeping my face forward as my eyes slide to her. “I can’t afford to be a starving artist.” And I was for a minute, when I was still trying to sell my art instead of my soul.

“Well, you do love carnival food,” she adds.

“I was cured of that by the third week.” I could gag even imagining corn dogs and, as a rule, I love phallic-shaped food.

“Where were you before Texas?”

“Here, there, and everywhere. I did a little bit of landscaping work in Tela, taught golf in Puerto Plata to tourists . . . I was a pool boy for a wealthy couple in Miami. . . . That type of shit.”

“You were a pool boy?” She laughs. “What do you know about pools?”

“I didn’t do much of the actual pool part of the gig, per se.”

Her face scrunches up in horror. “Oh god. Say less, please.”

I laugh. “Honestly, I was running out of money and Bertha definitely needed a break, so Nik’s SOS came at the right time.” I pause, considering what I just said. “Don’t—”

“I won’t tell him,” Nadia interrupts, pulling out her phone as she rolls her eyes. “Well, I think we’re all caught up,” she says, holding it up to the roof as if she’ll somehow get a signal that way. “Now what?”

“We should have paced ourselves better. What will we do for the rest of our two months together?”

“Right . . . two months . . .” She doesn’t look away from her phone.

“Nik said two months, right?”

She licks her lips quickly, forcing down yet another smirk. “He did say that to you, yes.”

“Nads . . . what do you know?” I ask, looking urgently between her and the road ahead. “Did you talk to Sef? What’s going on?” I knew Nik wouldn’t use his one-one-nine on a fucking bar opening. “Nadia!”

Nadia releases an incredulous laugh, her eyes glued to her phone as she scrolls. “You’ll have to wait and see, big brother.”

TWO

Prue

SLIDING ON MY favorite pair of fuzzy slippers, I step out into a breezy Sunday morning from my A-frame on my parents’ property and walk the short distance to their back porch.

Everything about my parents’ home is colorful: yellow siding interrupted by white-trimmed windows and doors, shades of orange and red and pink filling every inch of the garden beds, the perennial flowers on their last legs before they disappear until spring. Every post of the balcony railing is painted in a slightly different shade of blue, complementing the cobalt back door. A narrow, curving walkway was painted a calming shade of green, leading from the back door to the base of the four porch steps.

No part of our home was safe from my mother’s creativity or brush, inside or out.

I enter through the kitchen and find my dad at the table. “Top of the mornin’, Tom,” I say, brushing my palm over his bald head before darting to grab the chocolate donut on his plate out from under his nose. I take a bite, before he’s even noticed it’s gone.

“Mmm, delicious.” Brown crumbs spew out of my mouth as I speak, dusting his newspaper. “Did John try a new recipe?”

He chuckles, the apples of his cheeks rising alongside his cheery smile. “Tom? That is Father dearest to you, young lady.” He reaches out to take his donut back but I dodge him, my socks sliding against the hardwood floor as I take another bite.

Today is Sunday, which means a delivery of donuts from the bakery around the corner, owned by my father’s best friend, John. His shop, called John Dough, is a mainstay of our one-stop-sign, pass-through, tourist-trap of a town.

Well, technically, it’s not a one-stop-sign town anymore. They put in a traffic light last month. The townies even held a ribbon-cutting ceremony to celebrate, not that I was in attendance. The light was installed in anticipation of yet another business that will inevitably close its doors in a year, or even sooner once the owners decide the winters aren’t worth it.

Though I’ve yet to meet our newest neighbors, Dad—the Miss Congeniality of Baysville—has. He likes them fine, from the sound of things. Or, at least, he likes the sampler beer flight they sent him home with. He certainly likes them more than the couple who tried to open a grocery store three lots down a few years back. Groceries are his business, after all.

Resting along the main road connecting Baysville to the much larger surrounding towns of Huntsville and Bracebridge is Welch’s Gas and Grocer. It has been in our family for four generations now, as Dad proudly tells every new customer. It’s relatively big in comparison to the surrounding businesses. We have two gas pumps out front, then the storefront itself, which is a one-story windowed building attached to the front of the two-story, two-bedroom, yellow-slatted house my parents live in.

The A-frame out back was originally built for my parents when Dad began working for Grandpa after Mom had finished her teaching degree and took a job at the nearest high school. When my grandfather passed away, Mom and Dad moved into the yellow house and the A-frame became Mom’s art studio. In the two decades that followed, Mom worked as an art teacher while Dad ran the store, providing anything customers needed, from worms for fishing to overpriced cartons of eggs.

As the sign out front says . . . WELCH’S: WE’VE GOT WHAT YOU FORGOT.

The irony of this inherited slogan is not lost on us.

And, when Mom needed to move into her own bedroom, the loft above her studio became my chilly, spider-infested, cozy safe haven.

I take one last bite of Dad’s donut as he manages to grab hold of my elbow and tug me closer.

“Cheeky!” He swats my arm with his rolled-up newspaper as he steals the pastry back. “There’s one on the counter for you but now I want half of it.” The wooden chair underneath him scrapes against the uneven floorboards as he moves to shield his donut and coffee from me. He opens his newspaper with a flourish and writes something into the crossword with his pen, plucked from behind his ear.

I turn to look at the kitchen. A few feet from the table my father is sitting at, the countertops are so entirely covered in clutter and dirty dishes that I can barely see the grain of the butcher block beneath. It’s a visual reminder that these Sunday mornings, when the store opens later and Dad can sit down to eat his hand-delivered donut, read his paper, and rest his mind before work, are precious and needed.

I make my way over to the sink, wait for the water to warm, plug the drain, and get to work on last night’s dishes. Mom wanted soup, despite it being an uncharacteristically hot September day, so Dad and I made her favorite—French onion. Dad stopped by John’s for a fresh baguette, got lost in yet another conversation about the Beatles no doubt, and then visited Cheryl’s Deli after hours to pick up some Gruyère. All the while, I cut onions at the table, trying to keep Mom in conversation as she worked on another puzzle.

Mom’s recently been downgraded from five-hundred- to one-hundred-piece puzzles to avoid outbursts. I’ve spent too much time picking up puzzle pieces off the kitchen floor while Dad ushers her upstairs to not reduce the number of pieces.

That’s not her, I remind that bitter voice inside of my head. I scrub the baked-on cheese off the lip of Mom’s favorite blue bowl and scold myself once again for feeling frustrated.

That’s not her. If I don’t remind myself, I’ll cry. And I try not to do that much anymore. Mostly because I don’t have the time for it.

Though patience has never been my best skill, it certainly had been one of Mom’s. She raised her voice at me one time in my entire childhood. I remember it vividly because it felt so unnatural and foreign to her usual softhearted, gentle approach. I was trying to find my special pen and spent probably less than ten seconds looking for it before I ran to find Mom and make her look instead. Running into her studio, I managed to knock over an entire jar of freshly opened paint.

Truthfully, I had done that countless times. Mom was always leaving paint cans scattered around, having gotten pulled in a new creative direction that required immediate attention, and I was never good at looking where I was going. But that morning the jar of blue paint spilled all over the brand-new large canvas that Mom had just finished binding, and she snapped.

“Dammit, Prudence!” Two shouted words, one stunned expression shared between us, and then fits of uneasy laughter that slowly relaxed into resting smiles when Mom eventually grabbed a brush, turned that spilled blue paint into a picturesque sky, and invited me to help her make clouds.

That woman, who repurposed my mistakes and filled our home with color, was the architect of my childhood.

She kept me sheltered in her company in all stages and seasons. We spent long summer afternoons by the lake together, where she’d entertain each of my many, many terrible poems. We shared chilly autumn evenings huddled by the fireplace, listening to Dad playing the piano for us. We sat together on crisp winter mornings, snuggled under blankets with mugs of tea and bellies full of homemade oatmeal. We lost countless hours on hope-filled spring afternoons picking flowers in our neighbor’s unruly field.

That is why I stay, I remind myself. That is who she is.

I stay for the woman who handled me, an exposed nerve in a girlish form, with so much care. A woman who never pushed me too far away from her reach because she knew I was never quite ready to stand steadily on my own two feet. And for the man who loves her too. Because if I left, he’d have no choice but to lose us both.

Alzheimer’s has taken a lot from our family, mostly from Mom, but I refuse to give up the truth of who she truly is.

So, I will keep reminding myself. When I’m picking up puzzle pieces, or cooking soup on a hot day, or repeating myself for the hundredth time. I will continue to close my eyes and imagine her. The mother who held forgiveness, grace, and patience in limitless quantities behind her seashell-colored eyes. And I will try to offer those same qualities back to her in kind.

I will keep this family together.

“How did she sleep?” I ask, placing Mom’s bowl in the drying rack and looking over my shoulder toward Dad.

“All right, for the most part. She woke up a handful of times but settled easily,” Dad says, flipping the page of his paper, his eyes scanning it absently. “She was asking about painting again.”

I sigh out through my nose, pressing my hip to the counter before I pick up another dish. For the last few weeks Mom has been waking at night, desperate to get to her studio. Sometimes she thinks she’s left it unlocked, other times she just wants to paint. Dad always manages to convince her to get back into bed, but she’s growing more and more agitated.

“We can switch beds for a while, if you want,” I offer. “So you can catch up on—”

“No, sweetie. Thank you, though.” Dad takes a long sip of coffee. “I’m going to try and see what I can find later today around the house to tide her over. Maybe we can see if your aunt can come up for a visit next weekend to give us some time to clear out her studio for her.”

The studio has gone unattended for so long that getting it ready for her would be at least a two-day job. Between just giving everything a thorough clean and going into town to replace the supplies, it’s no easy task. But if that’s what Mom’s wanting, that’s what we’ll do.

“Aunt Lucy’s in Wales for the next month,” I say. “But I’ll take care of it. This week. I’ll get the studio cleaned up for her.”

“With what time?”

I can cut back on my writing, for sure. Reading too. If I make an effort to eat more fiber this week, I could gain back some time there as well. I could probably cut back to six hours of sleep, maybe even five. “Like I said, I’ll figure it out.”

“Maybe . . .” Dad clears his throat, and swallows so loudly that I can hear him from across the room. “Maybe, sweet, sweet daughter of mine, we could revisit the conversation around—”

“Don’t try and butter me up,” I say, wringing out my sponge. “Seriously, it’s fine. I’m fine.”

“Prue . . .”

“I’ve got it,” I say, turning on my heel to face him, my plastered smile dangerously near breaking into a scowl. “Let me take care of it. . . . Please.”

He rubs his chin furiously, then checks his watch when it catches his eye. I see the conversation play out in his mind, the same dance he and I have spun time and time again over the last several months. I feel his resolve settle between us the moment he realizes we don’t have enough time to rehash the same back-and-forth before he needs to leave to open the store.

We need help.

No, we don’t. We can’t afford it anyway.

Prue, you need to get out more. You need a life of your own.

I don’t. I’m good where I am.

Your mom would want you to—

Dad, please. I’m fine. Seriously.

You look tired.

Jeez, thanks.

We cannot do this forever, darling.

We can. Mom would.

Yes . . . But—

Dad, I promise I’m fine.

And then, regardless of whether we actually have the conversation or not, he will sigh and say, “Tonight, Prue. You and I need to sit down and have a real conversation about this. I mean it this time.”

Wait, no . . . That’s not how it’s supposed to—

“Good morning!” Mom singsongs, turning the corner from the bottom of the stairs toward us. She practically waltzes into the center of the room in her white silk robe and matching fluffy slippers, smiling and chipper and so . . . her-like. “Something smells good!”

“Julia,” Dad whispers in the same hushed, mesmerized tone he does anytime Mom shows up more like herself. As if she’ll startle and leave as quickly as she appeared. Or, as if he’s dreaming and afraid to wake himself.

My heart clenches too tight alongside a sinking feeling, knowing that Mom’s clearer days tend to mean our routine goes out the window. Remembering the grief we will experience tomorrow, when she’s left us again. I force a smile, dropping the sponge into the sink before I turn around to greet her, leaning my lower back against the counter. “Hi, Mom.”

She stops, tilting her head curiously at me as she lets out a restrained laugh, her playful eyes looking between Dad and me. “Mom?”

Oh.

She giggles dryly, greeting my dad with a kiss on his cheek as he rises to stand beside her. “Luce, did you just call me Mom?”

Thank you for joining us for another kitchen recital, ladies and gentlemen. This morning the leading role of Aunt Lucy will be played by her niece, Prudence Welch, once again.

It doesn’t hurt as much anymore, not like it used to. I do see the resemblance. Lucy and I share the same tightly coiled brunette hair, bushy brows, and pale skin. Whereas Lucy’s features are just right for her face, I think our similar lips are far too big for the narrower face I inherited from Dad. Additionally, my vivacious aunt can pull off the doe eyes we share. Unfortunately for me, they give the impression that I’m approachable. I’m not.

The hardest lesson I’ve had to learn over the past four years is that when someone begins losing their memory, it’s the short-term that goes first.

Imagine a home, Mom’s neurologist had told us, wherethe basement is the present and the attic is as far back as memories go. The home begins to flood, from the ground up.Like with a flood, some items will be salvageable, but most things will be lost. Similarly, some memories will survive whereas most will not. Level by level, you’ll see the water rise, irreparably damaging each room on its way.

Thankfully, days like this are rare. Occasionally, Mom will be confused as to why I look older, but we can usually get past that. But others, like today, when she hasn’t slept well or when she’s had a hard day the day before, her mind takes her to another time—a time, typically, before I existed. It’s her brain’s way of protecting her from her current reality.

Dad and I exchange brief, messaging glances. His says sorry. Mine says don’t be.

What, exactly, he’s apologizing for I’m not completely sure. It could be because he still gets days with Mom that I don’t. Or, because I’m not as good at pretending it doesn’t weigh on me as I’d like to think I am. Maybe he’s apologizing for this dreadful real conversation he’s decided we need to have later.

“Did I?” I squeeze out a laugh from the hollow of my chest, turning back toward the sink to shut off the running water. “Whoops!”

The most important rule when caring for someone with early-onset Alzheimer’s is and will always be: Play along. If you threaten their understanding of their current reality, they will panic. You want to avoid panic.

“I was just about to go open the store, Jules,” my dad says, bending down to kiss her, cradling her face in his hands. “But I’ll be right out front if you need me.”

“Ha, ha . . . Very funny.” Mom rolls her eyes, gently smacking him on the shoulder. When Dad hesitates, her face falls, and she brings her hand to hold his wrist, squeezing him as he rubs his thumb over her cheek. “You’re not serious, right?” A short, scattered, verging-on-hysterical scoff. “You’re not really going to work on our wedding day?”

I groan internally, allowing my eyes to shut as the exhaustion threatens to pull me under.

Three long seconds. Then my father releases a deep, clipped laugh. “Of course not, my bride. Of course not.”

And with that, our day just got a whole lot longer.

“You . . .” She shakes her head, smiling brightly up at him. “You tease too much!” She turns her attention toward me. “Why does everyone look so sad? It’s a wedding for Christ’s sake, not a funeral!” Her laugh is effervescent, sparking memories of loud townie Christmas parties, midnight cookie-dough feasting, and happy birthdays sung out of key.

I shake myself. “Sorry,” I say, walking over to them, reaching out for her hand. I take it tightly in my grasp, feeling her cool skin against mine. I make a mental note to insist that she wear a cardigan with her dress. “It’s just, I’m going to miss you . . .” I inhale, letting the truth exist for a brief second between us. “Two weeks in England is a long time.”

The VHS among the books on the living room shelves reads: England, 1993: Our honeymoon. I used to make my parents do a double feature on every anniversary. We’d make snacks, get dressed up, and then watch their wedding video. Then, Dad would cook a full British roast and we’d watch the memories of their honeymoon. Most years I would fall asleep to him softly playing her “Julia” by the Beatles on the piano as she danced for him. Just as they did the first night they met.

I wish I could tell her that.

I wish I could show her the video.

I wish she would show it to me again.

Mom presses her forehead to mine. “I’ll be back before you know it, Luce.” Then, with a tipped-up chin and a wink, she bolts, taking off toward the stairs with her robe fluttering behind her. “C’mon! And bring the champagne!” she yells.

Dad pats my shoulder, reaching into the cabinet where we store a collection of alcohol-free sparkling wine for this exact reason. We were caught without it once, and I will not be called the world’s worst bridesmaid again. Turns out, my mother is a bit of a bridezilla. “I’ll get John on the phone,” Dad says, handing me the bottle.

John keeps a spare cake in his deep freezer for days like this.

“I’ll put up the sign,” I reply, voice resigned. I walk toward the front of the house where a brightly painted purple door connects Dad’s office to the storefront. I reach to the back of the office’s closet, grab the CLOSED FOR A WEDDING sign, and make my way to the shop’s front door.

Clyde, the oldest man alive, who is also, tragically, my only real friend in town, is already waiting there for me. I unlock the top and bottom of the door, then push it open. “Morning, Clyde.”

He fixes his cap in greeting. “Good morning, doll.”

“We’re closed for the day, I’m afraid.” I hold up the sign to him before securing it with a binder clip to the shop’s hours sign. “Sorry.”

He nods slowly, reading it over. “Ah, no bother. I’ll pop by later for some cake then.” I watch as he begins to walk away, turning toward his daughter’s house across the street. “D’ya need Lynn to bring anything by?”

I shake my head no, and he nods.

“Thank you, though. See you later,” I say, knowing he’s already out of earshot. As soon as I step aside to make sure he’s gotten over the curb okay, a huge gust of wind forces the door open, slamming it against the store’s outer wall.

“Shit!” I startle, clasping my chest.

“Careful!” Clyde shouts, holding his hat in place. “It’s a windy one today!”

“Perfect day for a wedding!” I yell back sardonically, grumbling under my breath as I move to shut the door. “Tenth time’s the charm,” I whisper to myself, locking it in place.

My mother sewed me the most beautiful pair of wings.

She decorated them with lace, diamonds, and pearls.

Nothing too heavy, as to not weigh me down.

Nothing too light, to teach me my strength.

Then, she placed them on my back and hoped for the best.

Only, I didn’t want anyone else to see them.

—P.W.

THREE

Milo

“IT DOESN’T LOOK open,” Nadia says from the passenger seat, leaning forward to look around me and toward the gas station’s store.

“Maybe they’re closed on Sundays?” I say, flicking the fuel gauge. Sometimes, if I’m lucky and hit it just right, Bertha will tell me I’m low on gas before I run out of fuel. Today, I’m not so lucky. We’ll have to gamble that we’ve got enough to get to Nik’s place.

“Their Facebook page says otherwise.” She shows me her screen, where every item nearly past its sell-by date gets its own dedicated post in screaming all caps. “Open seven days a week,” she reads in her best radio-DJ voice, “Welch’s: We’ve got what you forgot.”

“Here’s a wild idea, you could just get out of the car and go check?” I offer a smile that is anything but sweet.

“Do you have cash on you?”

“No, why?”

“Okay, do you trust me with your PIN number?”

I squint at her, trying to decide.

“And did you or did you not swear in written testimony that you would buy me cigarettes?”

I groan.

“Exactly. Pay up, loser,” she says, shooing me with a flippant wave of her hand as she continues to scroll on her phone.

“You’re a pain in the ass.” I turn off the engine and toss the keys onto the dash.

I slam the van’s door behind me, mostly so the lock mechanism clicks into place, but also out of spite. Immediately the wind picks up, nearly blowing me sideways. My hair is tossed to one side and my unbuttoned gray flannel jacket folds up my back, flapping against my shoulders. “All of this for cigarettes she’s not even going to smoke,” I grumble, trying the shop’s door to no avail.

Cupping my hand to the glass, I check for signs of life.

“We’re closed.” Somewhere upwind, a woman speaks. I look to the other side of the small parking lot in the direction of the breathy voice and—

Whoa.

The wind threatens to carry all five-foot-nothing of her away, blowing chestnut curls loose from the woven braid that rests over her shoulder and pulling the baby-blue dress she’s wearing taut behind her—emphasizing each dip and swell of her silhouette in soft, inviting challenge.

“Rusalka,” I whisper in warning to any nearby men who may hear it. Run, something deep inside of me says.

I’ve never listened well to my intuition, or to anyone else’s, really. And, I’m far too intrigued to leave now. Intrigued and a bit frightened, which is new. Men are lured to their death by beautiful creatures time and time again in mythology. Different legends call them by different names: sirens, nymphs, pixies, faeries, rusalki. But the result is the same—death at the hands of a beautiful creature, too alluring to deny.

So fucking be it.

“Hello,” I call back, straightening my stance and turning to