Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Unicorn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

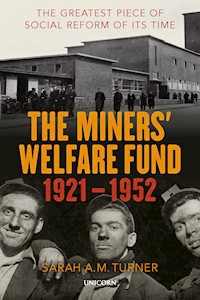

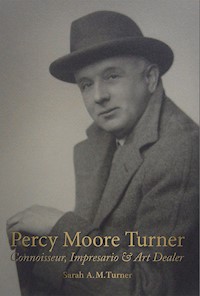

Grudgingly acknowledged as the main mentor for the Courtaulds in building their art collections, the London and Paris art dealer, Percy Moore Turner, is now largely forgotten in this country. Yet, in France, he was honoured by the French Government with the award of Officer and then Commander of the Legion d'Honneur and feted by the Museums of France with specially struck medals. In this, the first biography of Percy Moore Turner, his granddaughter, who has access to his few remaining business papers and unpublished autobiography, has researched his life and career. Involved with the Bloomsbury Group from before the First World War, he was actively courted by Roger Fry at the end of the War to manage an artists' association for them when Turner was still serving in the Army. Instead, Turner promoted them when he opened his London Gallery with some success until 1925 when the Group, embarrassed by the financial losses caused by them to him, 'sacked' him on friendly terms. Born in Halifax in 1877 into a family of hosiers and haberdashers, Turner's life and career spanned two World Wars and periods of economic volatility. He tirelessly promoted modern French art internationally and built up a client base which included Dr Albert Barnes, John Quinn, Charles Lang Freer, Samuel Courtauld, Russell Colman and Frank Hindley Smith. A longstanding friend of Kenneth Clark, Turner strove to ensure that his own art collection was placed appropriately in museums and galleries throughout Britain and France, considering himself merely the custodian of the pictures he owned. Contents: 1. Childhood - Halifax to Norwich 2. Getting started 3. Gallery Barbazanges 4. Starting again – The Independent Gallery 5. Exhibitions and the Oxford Arts Club 6. The War Years 1939-1945 7. The Final Years 8. Photographs and Illustrations 9. Postscript 10. Acknowledgements 11. Abbreviations 12. Index

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 347

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Percy Moore Turner

Connoisseur, Impresario & Art Dealer

Sarah A. M. Turner

Dedication

To my grandmother, Mabel Grace Turner, who stood by my grandfather through both good and bad times.

‘To finish, I must pay tribute to his sunny, generous, genial and tireless disposition until, in his later years, ill health and certain disillusionments led to regrettable changes of outlook and general character.’

Taken from Notes by Mabel Grace Turner on Percy Moore Turner’s account of his own career, written several years after his death.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I grew up knowing very little about the life of my grandfather but in July 2012 Dimitri Salmon, Collaborateur Scientifique at the Musée du Louvre, contacted my brother and me as he was researching the life of Percy Moore Turner. Dimitri has extensively researched the works of Georges de La Tour and he was particularly interested in the St Joseph, the Carpenter, which my grandfather had presented to the Louvre in 1948. This gave me the incentive to research my grandfather’s life in collaboration with Dimitri.

Although I have undertaken research in my own clinical speciality, I have no background in the history of art. The Turner family have very few of my grandfather’s papers, so his life has had to be mostly pieced together using his invaluable unpublished autobiography, letters, newspaper articles and exhibition catalogues. Some of these are written in French, so the titles of pictures have been given in French in those instances. The titles and attributions of pictures in the text have changed over time and the new titles have been included where possible. I have been unable to trace some pictures, perhaps because of these changes.

My grandfather wrote his unpublished autobiography in 1948. It is typewritten and my grandmother chose to preserve it as she thought that it might be of ‘some interest and even use to the family at some future date’. A few years after my grandfather’s death she added a handwritten preface to the manuscript. In this she explained: ‘It must be remembered that, at the time of writing, he was a very sick man and, by reason of his state of health and his enforced inactivity which left him so much time to fret and brood after such an active and interesting life, plus his anxiety about the eventual disposition of his artistic possessions, he had developed an extraordinary obsession with the importance of his achievements and an inordinate desire for full credit and recognition of them.’

The fifty-one page autobiography did omit some of the highlights of my grandfather’s life that I describe in Chapter 7, but it did provide invaluable leads to information that were crucial to the research into his life. Some parts of my grandfather’s autobiography I was unable to verify, such as his friendship with individuals linked with the Museo Nacional del Prado and his association with John Crome’s The Poringland Oak of around 1818–20, purchased by the Tate Gallery in 1910. These and other parts of his autobiography have not been included in the text.

To distinguish Percy Moore Turner from other members of his family mentioned in the book and the artist William Mallord Turner, I have used Percy rather than Turner as the abbreviated form of my grandfather’s name.

I hope this book will encourage art historians to research my grandfather’s life further.

Sarah A. M. Turner

1 CHILDHOOD – FROM HALIFAX TO NORWICH

Percy Moore Turner was born on 6 July 1877 in Halifax in Yorkshire. During the mid-Victorian era, the population of the borough of Halifax more than doubled, rising from 25,159 in 1851 to 65,510 in 1871, initially due to the expansion of the local textile industries.1 As the textile industries declined in the second half of the nineteenth century, Halifax’s population growth was sustained by an increasing diversification whereby Halifax earned a reputation as ‘a town of 100 trades’.2 These included confectionery, construction, engineering, cable and machine tool-making industries.3

Percy’s Father, Thomas Turner (1845–1906)

Percy’s father, Thomas Turner (1845–1906), was listed by profession in the censuses for England as ‘a hosier’ (1861), ‘a master hosier employing 4 girls and boys’ (1871), ‘hosier’ (1881), ‘living on his own means’ (1891) and ‘a retired hosier and haberdasher’ (1901).4 In the Halifax local trade directories, he is listed as ‘a hosier at 13 Old Market’ (1867),5 ‘a hosier at 14 and 16 Old Market’ (1871),6 under the category of hosiers and glovers at 14 Old Market (1887),7 and as ‘a hosier at 14 and 16 Old Market’ (1889).8 In the Turner Family Papers there is a brass printing plate illustrating Thomas Turner’s shop at 12 and 13 Old Market, which was a ladies’ outfitter, Berlin wool and fancy repository, hosier, glover and shirt maker. It has not been possible to identify when Thomas Turner opened his shop but it was sold in 1889 when Thomas Turner and his family moved to Norwich.9.

Thomas Turner’s shop at 12 and 13 Old Market

Percy’s mother was Sarah Jane Robotham (1844–1928). Her father was a hosier and haberdasher.10 Sarah married Thomas on 2 February 1870 at St John the Baptist Church in Halifax.11 On 13 March 1879, fifteen months after Percy was born, Sarah gave birth to his sister Maud Ethel Moore Turner.12 The family lived at 14 and 16 Old Market, Halifax until 1889.13

Sarah Jane Robotham (1844–1928), Percy’s mother

Percy and Maud Ethel Moore Turner, taken in Halifax, 11 June 1881 (Thomas Turner’s birthday)

Percy and Maud Ethel Moore Turner, taken in Halifax, 11 June 1883

Percy and Maud Ethel Moore Turner, taken in Halifax, 11 June 1885

The Turner family at 42 Mill Road, Norwich

Thomas Turner was advised by his doctor to move to a drier climate in 1889, so he retired and the family moved to 42 Mill Hill Road, Norwich. Thomas brought his extensive art collection with him, which included a fine collection of old master line engravings, chiefly after Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, inherited from his brother, who had died young. He also owned a few good oil paintings, one by the School of Titian, a William Hogarth, a Salvator Rosa and an Abraham or Jacob van Strij. He contined to add to his collection while living in Norwich and gradually acquired numerous minor examples of the Norwich School. The Turner family at 42 Mill Road, Norwich Percy frequently accompanied his father when making his purchases. All of this hugely impressed Percy as a boy.14 On 25 February 1895 Thomas Turner sold engravings and mezzotints through Sotheby, Wilkinson and Hodge in London in twenty-nine lots.15 In 1897, Thomas instructed Maddison, Miles and Maddison of Great Yarmouth to sell a number of oil paintings, drawings, etchings, coins, books, microscope and musical instruments as he was considering making structural alterations to his house. There were 102 lots of oil paintings, including paintings by J.M.W. Turner, Rubens, Van Dyck, the Norwich School, Rembrandt, Paolo Veronese and Thomas Gainsborough, and seventeen lots of watercolours, including those by Gainsborough, J.M.W. Turner and Sell Cotman. Out of twenty-five lots of drawings, seven were from the collection of the late Reverend E.T. Dawell, including those by John Crome and John Sell Cotman. Engravings by Edwin Henry Landseer, Adriaen van Ostade, Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds were included in the forty-six lots of engravings.16

Percy and Maud Ethel Moore Turner at 42 Mill Road, Norwich

Both Percy and Maud attended Norwich Higher Grade School in Duke Street,17 which was a working class secondary school opened in 1889.18 It has not been possible to find out the age at which Percy left school. Certainly, he was still at school in 1891,19 and it is possible that he did not leave school until 1893. Although the Elementary Education (School Attendance) Act of 1893 increased the school leaving age to eleven,20 boys at Norwich Higher Grade School were encouraged to sit the Cambridge Local Examinations.21 These examinations could not be sat until the December a pupil had reached the age of sixteen.22

The boat and shoe trades were among the principle industries in Norwich and Percy’s parents thought they might present an admirable career for him. Accordingly, he entered the employment of Hales Brothers, a shoe business in Westwick Street, Norwich, where he remained for a number of years.23

In November 1894 Percy visited a loan exhibition of pictures and watercolour drawings held at the Agricultural Hall Gallery, Norwich, during the Grand Oriental Bazaar. The pictures were by deceased artists of the Norwich School, including John Sell Cotman, John Crome, Joseph Stannard and James Stark, with the MP J.J. Colman loaning the largest number of works. The preface to the exhibition catalogue was written by Henry G. Barnwell and Robert Bagge Scott.24 In 1925, after the death of Robert Bagge Scott, Percy wrote that the preface was ‘full of sympathetic perception, and still more important, full of hints to guide a public, in whom responsiveness was largely latent, into paths of appreciation of the best in art. That preface made a profound impression upon me and my joy was unbounded when a fortuitous incident arising out of the exhibition enabled me to meet him.’25

Robert Bagge Scott (1849–1925) was born in Norwich in 1849 but was mainly educated in France. Although he qualified as an officer in the Merchant Navy and travelled the world, he decided to pursue a career in art and was admitted as a student to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp, under Albert de Keyser. He also attended lessons with the landscape painter Jozef van Luppen. After travelling extensively in France and Holland, which provided him with the subjects for his pictures, he married a Dutch women and returned to Norwich where he became actively involved in the artistic life of the city.26

A friendship between Percy and Robert Bagge Scott sprang up that terminated only with the latter’s death in 1925. During the early years of Percy’s career in art, he frequently met up with Bagge Scott. After Bagge Scott’s death, Percy wrote that ‘I owe to him more than I can express.’ 27

It was only when Percy’s father bought a small Dutch School oil painting on copper of the head of a peasant that Percy resolved to find a way to quit the boot business and enter the art business. There were no facilities for studying the old masters or art in Norwich so he had to find some means of going to London.28

NOTES

1. Hargreaves, John A., Halifax (Carnegie Publishing, Lancaster, 2003), p. 127.

2. Ibid., p. 128.

3. Ibid., p. 131.

4. Censuses, England, National Archives.

5.Kelly’s Directory of the West Riding of Yorkshire, 1867.

6.Kelly’s Directory of the West Riding of Yorkshire, 1971.

7.Slater’s Royal National Commercial Directory of Yorkshire, 1887.

8.Kelly’s Directory of the West Riding of Yorkshire, 1889.

9. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, p. 1.

10. 1851 Census, England, National Archives.

11. West Yorkshire, England, Marriages and Banns 1813–1935.

12. England and Wales Free BMD Birth Index 1837–1915; West Yorkshire, England, Births and Baptisms 1813–1900.

13. 1881 Census, England, National Archives.

14. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, p. 1.

15.Catalogue of Miscellaneous Engravings and Watercolours, including the properties of Thomas Turner Esq. of Norwich sold by Auction by Sotheby, Wilkinson and Hodge (National Portrait Gallery, London, 1895), pp. 6–7.

16. CIL: Catalogue of the valuable collection of oil paintings, drawings, prints, etchings, coins, books, microscope, musical instruments, etc. with Maddison, Miles and Maddison held at 42 Mill Hill Road, Yarmouth, on Monday 5 April 1897.

17. PMT military service history, 8 December 1915; scrapbook concerning school events. Norfolk Records Office D/ED 23/11/746X3.

18. Rawcliffe, Carole and Richard Wilson (eds), Norwich since 1550 (Bloomsbury, London, 2004), p. 305.

19. 1891 Census, England, National Archives.

20. Education leaving age. Accessed 17 August 2017, http://www.politics.co.uk/reference/education-leaving-age

21. Scrapbook concerning school events, Norfolk Records Office D/ED 23/11/746X3.

22. Raban, Sandra (ed.), Examining the World (CUP, Cambridge 2008), pp. 38–40.

23. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, p. 1.

24. Norfolk and Norwich Millennium Library NL00031609.

25. Moore Turner, Percy, ‘Bagge Scott Exhibition’, Eastern Daily Press, Wednesday, 17 June 1925.

26.Norfolk and Norwich Art Circle 1885–1985: a history of the Circle and the Centenary Exhibition 1985 (Circle, Norwich, 1985), p. 27.

27. See above, n. 25.

28. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, pp. 1–2.

2 GETTING STARTED

In 18971 Percy started applying to numerous jobs advertised in the Daily Telegraph. As a result of one of these applications, Frederick Tew appeared in person at 42 Mill Hill Road and engaged Percy on the spot as a prospective salesman for his leather business based in Edmund Place, Aldersgate. The business made mostly saddlery and travelling cases on commission for various clients in London.

Percy and Maud Ethel Moore Turner, taken in Norwich, 11 June 1897

At Frederick Tew’s instigation, Percy went to live with Tew’s widowed sister-in-law at North Villas, Camden Square, where Percy was provided with everything except his midday weekly meal. The wages were low and Percy had difficulty making ends meet, but this employment did afford him the opportunity he wanted. He cut short his midday meal, eating a couple of scones on the bus as he went to and fro the National Gallery, in order to steal a half hour or so for study. Saturday and Sunday afternoons were given over to study at the National Gallery, the Wallace Collection and South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). His tastes were catholic and embraced not only pictures but also any kind of work of art. His evenings were devoted to studying French, German and Spanish at a polytechnic, having violin lessons as he was passionate about music and playing in many amateur orchestras and in friends’ quartets. These activities so stretched his finances that, more often than not, he had to walk home to Camden Square as he could not afford the bus fare home.

It was not long before Percy had decided that he must somehow visit the galleries of Europe. Eventually he managed to save £5 and took advantage of a Sunday League Easter excursion to Antwerp and Brussels, which gave him two days in each city. Later, he took advantage of a Sunday League Whitsuntide excursion to Paris.2 By 1901 he had moved to Islington and was lodging with the Baker family at 19 Sparsholt Road. He now made his living as a fully fledged leather commercial traveller.3

In August 1901 Percy’s article illustrated by Robert Bagge Scott, ‘The Artist on the Ramble Down the Yare and Bure’, was published over two issues of the Art Record, an illustrated review of the British art scene. Starting in Norwich, Percy described the scenery along the Yare, Bure and Waveney rivers, the Norfolk Broads and the coast near Yarmouth that could appeal to an artist. Percy finished the article with the remark that it was only by studying the county and feeling the scenery of Norfolk that Crome could appear in his true light, second to none other than the seventeenth-century Dutch artists Jacob van Ruisdael, Meindert Hobbema and Aelbert Cuyp.4 Beginning in September 1901, Percy’s ‘The Ethics of Taste’ was published in nine parts in the Art Record, in which he systematically discussed the question ‘What is Art?’. At the end of part nine (published in February 1902), it was implied that there would be further parts to the discussion but none were published subsequently.5 In October 1901 the Art Record published Percy’s comprehensive review of the ‘Third Exhibition of the International Society of Painters, Sculptors and Gravers’ held at the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours in Piccadilly. This review started with the seven works by the President of the Society, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and concluded with the sculptures which, in Percy’s opinion, were the weak point of the exhibition.6

Percy as a leather salesman, c. 1900

According to Percy’s unpublished autobiography, Percy and Tew fell out in 1902. Percy was largely to blame. He was now unemployed with no resources behind him. Quite by chance, while looking for another job, Percy saw a French art firm opening premises in Old Bond Street. He went in and had the good fortune to encounter the proprietor, Jules Lowengard of the boulevard des Italiens, Paris. Percy asked Lowengard whether he required an assistant. At first, Lowengard was hesitant, but, finally, he asked Percy whether he knew anything about works of art. After putting Percy through an examination, Lowengard engaged him on a small wage, with Percy starting work the next morning.

The entire personnel consisted of a French man, Émile Molinier, a couple of porters and Percy.7 Émile Molinier (1857–1906) was born in Nantes in 1857 but educated in Paris, firstly, at the Lycée Charlemagne and the École Nationale des Chartes where he obtained an archivist diploma in palaeography in 1879. The same year, he started work in the Louvre in the Department of Sculptures and Objets d’Art from the Middle Ages, Renaissance and Modern period. In 1889 he was appointed as a lecturer at the École du Louvre and collaborated in the organisation of a retrospective exhibition of French art at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. He was promoted to professor in 1890 at the École du Louvre. In 1892 he was promoted to Assistant Curator and then, in 1893, to Curator of Objets d’Art of the Middle Ages, Renaissance and Modern period in the Musée du Louvre.8

Émile Molinier

Émile Molinier’s career at the Louvre was marked by important research on the works in his care and by the special relationship he fostered with collectors, which resulted in him writing about fifteen catalogues on major private collections, including the collection of Frédérick Spitzer. During the sale of the Spitzer collection in 1893, Molinier was accused, in terms laced with anti-Semitic sentiments, of colluding with the collector’s family for financial gain.9

In 1898 he was implicated in the Dreyfus affair, having signed on 23 January a second address in support of Émile Zola who had published ‘J’accuse’, an open letter addressed to the President of France that appeared on the front page of the newspaper, L’Aurore, on 13 January 1898.10 It accused the government of anti-Semitism and the unlawful jailing of the Jewish army officer Alfred Dreyfus. In 1902 Émile Molinier resigned from the Louvre, taking early retirement.11

Two days after Percy’s engagement, Molinier asked Percy whether he spoke French as he did not speak a word of English. Imperfect as Percy’s French was, Molinier was much relieved from that moment. Realising how keen he was, Molinier took a great interest in Percy who became his pupil for the next three years. Jules Lowengard encouraged this situation as, if anything happened to Molinier, Lowengard had nobody to fall back on but Percy. Percy, therefore, occasionally accompanied Molinier on continental journeys and to Ireland, a place that Molinier had long wished to visit but up until then had not due to the language difficulties.12

In September 1904 Percy’s article, ‘The House and Collection of Mr Edgar Speyer’, was published in the Burlington Magazine. The article described the house and the contents in detail, expanding on its three styles: Gothic, Renaissance and the prevalent style of the reigns of Louis XIV, XV and XVI in France.13

In 1905 Lowengard and Molinier quarrelled and Molinier left for Paris to establish his own business. Percy became manager of the London business and frequently travelled to Paris for work. Percy also travelled the continent for Lowengard, chiefly couriering important works of art. While travelling, Lowengard gave Percy free time and the opportunity to see and study great public and private collections in Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Belgium and Holland. Percy came into personal contact with the most important continental directors and collectors.

In London Percy conducted substantial business on Lowengard’s behalf with American and English collectors.14 In 1906 Percy unsuccessfully asked Lowengard for better remuneration.15 Thus when Percy had an offer from friends to establish a gallery in Paris in association with the then joint editor of the Burlington Magazine, Robert Dell, Percy and Lowengard parted, but on the best of terms.16

In 1903 Robert Edward Dell (1865–1940) helped found and became the first editor of the Burlington Magazine, together with the art historians Bernard Berenson, Herbert Horne and Roger Fry. The intent was to produce a British art journal for the serious art scholars and connoisseurs. The magazine, however, was losing money and in the same year Fry appointed Charles J. Holmes as co-editor.17 In October 1906 Dell resigned from the joint editorship of the Burlington Magazine18 in an apparent power struggle with Fry.19

Percy moved to Paris and took a flat in the rue Vaneau and he and Robert Dell opened Galeries Shirleys at 9 boulevard Malesherbes where they ran a series of exhibitions.20 The first exhibition was in December 1906: ‘The Retrospective Exhibition of Watercolours and Drawings by English Masters of 18th and 19th Century’. Percy’s father had died, just before its opening, in Norwich on 15 November 1906.21 The foreword was written by Percy,22 and one of his father’s exhibited paintings, The Glade by John Crome, was fittingly reproduced as the frontispiece for the catalogue. This picture would subsequently be given by Percy to the Castle Museum in Norwich with thirty-seven other drawings by Crome in May 1935 through the National Art Collection Fund.23 The exhibition was reviewed in The Times in England24 and in L’Aurore in Paris.25

John Crome, The Glade, pen and ink with wash on paper, 129.5 x 104.1 cm, undated

A short interlude in England followed: at the end of December 1906, Percy returned to London to marry Mabel Grace Wells (1884–1978). Their wedding took place on 28 December at St Mary’s Church, Hornsey Rise, London.26 A further seven exhibitions held at Galeries Shirleys have been identified: ‘Exhibition of Drawings by Aubrey Beardsley, 1872–1898’ (February 1907);27 ‘Retrospective Exhibition of Pictures by Adolphe Monticelli’ (12 April–4 May 1907);28 ‘Exhibition of English Decorative Art by Miss Birkenruth, Misses Casella and Miss Halle’ (17 May–15 July 1907);29 ‘Pictures by Old Masters’ (December 1907);30 ‘Exhibition of French Watercolours and Drawings’ (February 1908);31 ‘Watercolours and Drawings by Charles Louis Geoffroy[-Dechaume]’ (March 1908);32 and ‘Drawings of the French Masters of 18th Century and the School of 1830’ (April 1908).33

During this period, a number of Percy’s articles were published: ‘The Representation of the British School in the Louvre I – Constable, Bonington and Turner’ (1907);34 ‘The Representation of the British School in the Louvre II – Gainsborough, Hopper and Lawrence’ (1907);35 and ‘Philips and Jacob de Koninck’ (1909).36 He also wrote three books: Van Dyck (1908),37Stories of the French Artists from Clouet to Delacroix, collected and arranged by P.M. Turner (chapters 1–17) and C.H. Colin Baker (chapters 18–30) (1909),38 and Millet (1910).39

However, as time went on, Dell, who had become not only the Paris representative for the Burlington Magazine but also the Paris correspondent of the Manchester Guardian, became more and more absorbed in extreme politics.40 He had joined the Fabian Society in 1889 and had converted to Roman Catholicism in 1897. In 1906 the Aberdeen Free Press printed that ‘Mr Robert Dell […] deplores and condemns the aggressive attitude of the Papacy in France.’41 Dell held stimulating meetings at his flat near St Clothilde, which Percy attended. However, all this badly affected the business, and clientele gradually deserted the gallery, which was forced to close down in 1910.42

Percy moved to a flat in the rue Rouget-de-l’Isle, where he acted as Paris representative for W.B. Paterson of Old Bond Street, London, buying and selling. Percy found that Paterson lacked an understanding of the Paris and continental markets and their relationship became increasingly difficult despite remaining amicable.

Percy also extended his circle of influential friends in Paris and the continent. These friends included curators at the Louvre – Paul Jamot, Jean Guiffrey and Paul Vitry – art dealers, auctioneers and artists. He knew, to a varying degree, Auguste Rodin, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Jean Marchand, Othon Friesz, Raoul Dufy, Charles Dufresne, Jean-Louis Boussingault, Luc-Albert Moreau, Henri Matisse, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Aristide Maillol and Charles Despiau.43 In September 1911, Percy’s article, ‘The Painter of A Galiot in a Gale’, was published in the Burlington Magazine,44 and Percy and James Reeve, a consultant to and former Curator of the Norwich Castle Museum,45 disagreed over the attribution of the Tate’s Near Hingham (now Hingham Lane Scene, Norfolk after John Crome) and a John Sell Cotman at the National Gallery printed in the Eastern Daily Press.46

Around November 1911 Percy approached Henri Barbazanges, owner of Galerie Barbazanges, with a proposition to set up a gallery with him using English capital. Barbazanges would be the director for Paris and France and Percy would be the director for foreigners. Barbazanges declined this offer,47 but Percy and Barbazanges would both be involved with Galerie Levesque et Cie, which was established in Galerie Barbazanges in 1912.

NOTES

1.Who’s Who in Art (The Art Trade Press, Havant, 1927), p. 239, and Who’s Who in Art (The Art Trade Press Ltd, Havant, 1929), p. 464.

2. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, pp. 2–3.

3. 1901 Census, England, National Archives.

4.Art Record, vol. I, 17 August 1901, pp. 406–8, and vol. II, 31 August 1901, pp. 438–40. The Art Record was published weekly at this point, later monthly.

5.Art Record, vol. II, 1 September 1901, pp. 481–2; 28 September 1901, pp. 497–8; 5 October 1901, p. 515; 12 October 1901, pp. 539–40; 2 November 1901, pp. 597–8; 9 November 1901, pp. 607–8; 16 November 1901, pp. 628–9; 23 November 1901, pp. 661–2; February 1902, pp. 706–8.

6.Art Record, vol. II, 19 October 1901, text pp. 545–8 and 565–8, illustrations pp. 549–64.

7. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, p. 3.

8. Tomasi, Michele, ‘Émile Molinier’. Institute national d’histoire de l’art, France. Accessed 14 September 2017, https://www.inha.fr>publications>molinier

9. Bos, Agnes, ‘Émile Molinier, the “incompatible” roles of a Louvre curator’, Journal of the History Collections, December 2014.

10. Tomasi, Michele, ‘Émile Molinier’. Institute national d’histoire de l’art, France. Accessed 14 September 2017, https://www.inha.fr>publications>molinier

11. Dossier de Personnel d’Émile Molinier F2 4036. Archives nationales, France.

12. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, p. 4.

13.BM, vol. 5, no. 18, pp. 544–5.

14. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, pp. 4–5.

15. LSE: DELL/7/3, Manchester Guardian, 22 July 1940, states 1905 but the first exhibition at Galerie Shirleys did not take place until December 1905.

16. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, p. 5.

17.Dictionary of Art Historians. Accessed 14 September 2017, https://dictionaryofarthistorians.or>dellr

18.BM, vol. X, no. 43, October 1906, p. 6.

19.Dictionary of Art Historians. Accessed 14 September 2017, https://dictionaryofarthistorians.or>dellr

20. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, pp. 5–6.

21. England and Wales Free BMD Death Index 1837–1915; England and Wales National Probate Calendar 1858–1966.

22. Robert Dell archives DELL/7/15, LSE.

23. TFPs: Stock Book A3, PMT 2149-2181; Report of Museums Committee 1929–39, Castle Museum, Norwich.

24. ‘English Water-colours in Paris’, The Times, Monday, 24 December 1906, p. 13.

25. ‘Les aquarellistes anglais à Paris’, L’Aurore, 4 January 1907, p. 2.

26. London, England, Marriages and Banns 1754–1921.

27. Robert Dell archives DELL/7/15, LSE.

28.BM, vol. 11, no. 49, April 1907, np.

29. Paris, Bibl. Des Arts Deco Br. 2213/50.

30.BM, vol. 12, no. 57, December 1907, p. ii.

31.BM, vol. 12, no. 59, February 1908, p. ii.

32.Bulletin de l’Art ancien et moderne, no. 375, 14 March 1908, p. 85.

33.BM, vol. 13, no. 6, April 1908, np.

34.BM, vol. 10, no. 48, March 1907, pp. 340–43, 346–7.

35.BM, vol. 11, no. 51, June 1907, pp. 136–9,142–3.

36. BM, vol. 14, no. 72, March 1909, pp. 328, 360–61, 364–5.

37. Published by T.C. and E.C. Jacks in London and Frederick A. Stokes in New York.

38. Published by Chatto and Windus, London.

39. Published by T.C. and E.C. Jack in London and Frederick A. Stokes in New York.

40. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, p. 5.

41. LSE: Robert Dell Archives, DELL/6/2. The Aberdeen Free Press, 11 October 1906.

42. LSE: Robert Dell Archives, DELL/7/3. Manchester Guardian, 22 July 1940.

43. TFPs: unpublished autobiography PMT, p. 6.

44.BM, vol. 19, no. 102, September 1911, pp. 326–2.

45. Norwich Castle Museum Committee Report 1910.

46. CIL: PMT archives, PMT-3-06, Eastern Daily Press, 30 September, 11 and 17 October 1911.

47. JFA: Letter Henri Barbazanges to Jean Frélaut, 11 September 1911.

3 GALERIE BARBAZANGES

Judging from the dates of the exhibition catalogues, it would appear that Galerie Barbazanges had been founded by Henri Barbazanges in around 1904. The gallery was initially based at 48 boulevard Haussmann before moving to 109 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré,1 a new building built by the celebrated dressmaker Paul Poiret.2 Unfortunately it was difficult to attract visitors to the exhibitions held at this large gallery.3

In 1912 a proposition was made to Percy to join his friends, Roger Levesque de Blives and Henri Barbazanges, in a new business, Levesque et Cie.4 In July Roger de Blives took over Henri Barbazanges’s gallery and business, the finance being provided by Joachim Violet whose family had invented Byrrh, the wine-based apéritif. Barbazanges stayed on in the gallery but Percy set up a business arrangement with de Blives, whereby Percy did not go into the business but instead sold pictures from his own flat and gave up representing Paterson.5

The gallery was mostly devoted to modern art but old masters were not neglected. In addition to Violet’s considerable capital, the gallery had access to Prince de Wagram’s collection of modern paintings,6 and was involved in their sale. Violet looked after the finances and Percy became the travelling representative, as he was the only member of the firm to speak any language other than French. He built up connections in America, Canada, Spain, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Holland, Scandinavia, Ireland and Scotland. He also acted for Charles Vignier (1863–1934) who was the expert on Asian arts at the Parisian auction house Hôtel Drouot.7

In July 1912 Roger Fry organised an ‘Exposition de Quelques Artistes Independent Anglais’ at the gallery. Besides Fry, Vanessa Bell, Frederick Etchells, Jessie Etchells, Charles Ginner, Spencer Gore, Duncan Grant, Charles Holmes, Wyndham Lewis and Helen Saunders were represented.8 Later that summer Percy returned to England for the birth of his only son, Geoffrey (1912–58). Geoffrey was born at Sutton in Norfolk on 16 August.9

In October 1912 the French artist Jean Frélaut held his first exhibition (thirty-seven paintings) at Galerie Barbazanges, and it is here that Barbazanges introduced Frélaut to Percy10 – the start of a very significant relationship that endured until the end of Percy’s life.

Percy’s wife, Mabel Grace, and their son, Geoffrey

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, The River (La Rivière), oil on canvas, 129.5 x 252.1 cm, c. 1864

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Cider (Le Vendange), oil on canvas, 129.5 x 252.1 cm, c. 1864

A few months later, in February 1913, Percy was in New York staying at 718 Fifth Avenue, while he was trying to sell two Puvis de Chavannes: La Rivière (around 1864) and Le Vendange (around 1864). They were Puvis’s scheme for two of the Amiens panels that were selected by the French government for the Paris Exhibition of 1900. Percy had offered the pictures to the collector John Quinn11 for $28,000 in instalments but an American museum, the Worcester in Massachusetts, was interested in them. The museum asked to loan them for a couple of months if Quinn did not take them.12 During this time Percy also managed to have an article, ‘Pictures of the English School in New York’, published in the February edition of the Burlington Magazine.13

In March, John Quinn agreed to purchase the two pictures but preferred to exhibit them in New York rather than at the Worcester, giving public credit to Percy or Levesque et Cie.14 In May 1913 Percy, writing to Quinn from his flat at 19 rue d’Anjou, confirmed that the two Puvis de Chavannes came directly from Prince de Wagram who had bought them from the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel who, in his turn, purchased them from Puvis in 1894.15 On 12 June 1913, Percy wrote to Quinn from Paris asking whether he was coming to Europe as Percy had just acquired a masterpiece by Paul Gauguin that he would like to show him.16

On 27 June 1913, Barbazanges wrote to Jean Frélaut, announcing that Percy was in New York on the track of an extraordinary client who would put the gallery in a good position if he bought pictures. Percy was going that night to present Frélaut’s pictures to the Director of the Metropolitan Museum and he was planning an exhibition of them in America. Barbazanges predicted that Percy would do well for Frélaut.17

A couple of months later, on 2 August 1913, Quinn confirmed that he was unable to go abroad, but he asked for more details of the Gauguin. He asked for a reprieve in paying for the last instalment on the Puvises, as a large fee he was expecting had yet to arrive, and indicated that he would want to pay for the Gauguin in instalments if it were a considerable amount.18

On 22 August, Percy confirmed that Quinn could send a cheque around 20 October when he received his money. As for the Gauguin, this was the celebrated canvas of which Gauguin speaks in his letter from Tahiti, reproduced in a well-known life of the artist. Gauguin inscribed its title on the canvas, d’où venons-nous, que sommes nous, où allons nous (Where do we come from? Where are we? Where are we going?) and dated it 1897. It caused a sensation in the Paris art world, and there was even talk of a national subscription for the purpose of presenting it to the Musée de Luxembourg. Levesque et Cie wanted $30,000 for it.19 Gauguin had painted this picture after his failed suicide attempt in Tahiti. He bought the picture back to France and sold it to a man in Bordeaux from whom de Blives and Percy bought it.20

In November, John Quinn declined the Gauguin as the price was out of his reach for the next year or so.21 In 1913 Percy was also listed among the visitors to see Michael Sadler’s pictures at 41 Headingley Lane, Leeds. Michael Ernest Sadler (1861–1943) was then the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Leeds.22

Paul Gauguin, Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?, oil on canvas, 139.1 x 374.6 cm, 1897–98 (left side detail)

By February 1914 Percy was back in New York for a fortnight, taking with him pictures by Paul Cézanne, Gauguin and Édouard Manet among others, which he is was keen to show John Quinn.23 While in New York, Percy was contacted by Dr Albert Coombs Barnes, an American physician, chemist, businessman and art collector who went on to establish the Barnes Foundation in 1922. Barnes thought Percy’s firm could do good business with paintings by two or three Americans. Barnes particularly recommended William Glackens and suggested that he bring him to their meeting so that Glackens could talk to Percy and arrange a visit to his studio.24 During the first half of 1914 André Dunoyer de Segonzac had his first solo exhibition at Galerie Levesque.25 Segonzac had been exhibiting his work since 1908 and his work had been included in a group exhibition at Percy’s friend’s Galerie Marseille in 1913.26 Judging from a letter Segonzac wrote to Percy in 1950, it would appear that Percy and Segonzac first met in 1914.27

At the beginning of August 1914, with the World War I about to break out, Percy luckily just managed to escape from Berlin on the last Nord Express to leave Germany for Paris. He found Paris in pandemonium, with the French forces being mobilised. Roger de Blives and Barbazanges had received their provisional mobilisation papers. Violet was too old for active service. Roger de Blives went to see Théophile Declassé, the French foreign minister, who reassured de Blives about the political situation. Assured, Percy proceeded to London to carry out business on behalf of the firm before joining his family for their annual holiday in Norfolk. Here, he received a telegram from de Blives asking him to return as quickly as possible to Paris, as de Blives and Barbazanges had received their calling-up papers and had had to leave Violet alone in the gallery.

With the mobilisation of the British army, Percy failed to get further than London; after many abortive attempts to get to Paris, he returned to Norfolk. He had only £25 in his English bank, so he was forced to borrow money which set a pattern until the end of World War I.28

In November 1914 Percy was still living at the holiday cottage that he and his family took each year, known as Haslemere in Stalham, Norfolk. He had been drafted into the Norfolk Special Constabulary, as he had been exempted from the military for medical reasons. As there were more than enough people in the force, he had been able to visit Paris in November and December to open up the business, settle the accounts and pay the taxes. He was the only member of the firm not mobilised.

The gallery still had a large amount of stock, but also owed a considerable amount of money, both in Europe and America. During his November visit, Percy offered to stay on, but Violet rejected this offer. Due to a moratorium in force in France, Percy was unable to take out any of his money. Violet refused to advance Percy any money either in France or in England, so they had a row and Percy left and never saw him again.29

In January 1915 Percy returned to the gallery. Henri Barbazanges seemed to have been discharged from the army since he informed Jean Frélaut by letter that he was going to the gallery three times a week to reply to letters and to receive clients who had not bought anything. As Percy had wanted to see all of Frélaut’s pictures again, he and Barbazanges had made their own exhibition.30

By March 1915 Percy had moved to Alanhurst, his sister-in-law’s family house, in Gerrards Cross, Buckinghamshire. He visited Paris to find business at a standstill. He had, however, been able, at last, to get in touch with Prince de Wagram about the Renoirs for Dr Albert Coombs Barnes. Prince de Wagram was fighting on the front and was not in a postition to part with any of his pictures.31

Multiple portrait of Percy c. 1917

Percy as a Private in 2/1st Northern Cyclist Battalion, February 1917

Percy in uniform as a Second Lieutenant, June 1917

Percy with the 67th (2nd Home Counties) Division

At the end of March 1915, knowing that John Quinn was interested in Charles Edward Conder, Percy wrote to Quinn about the potential opportunity to buy the finest collection of Conder’s works in existence. Previously the owner would not have thought of selling it but Percy thought that an offer of £8,000 would tempt him. In April, Quinn informed Percy that he was interested in Conder’s work, but it was beyond his reach at the moment.32

On 9 May 1915 Roger de Blives was killed at Arras.33 Levesque et Cie was put into the hands of the lawyers to protect the rights of Roger de Blives’s wife and daughter under French Law. Henri Barbazanges, having been discharged from the army on the grounds of ill health, was appointed as caretaker for the gallery by the government. Unable to sell anything without official sanction, Barbazanges was given a small salary and was left free to deal on his own account outside the business.34

At the beginning of June 1915 Percy was in Paris again. He felt that the executors may decide to sell Levesque et Cie and if so, he believed he might be able to buy it on advantageous terms if he could secure sufficient capital. He asked Barnes to back him but Barnes’s money was committed elsewhere.35